Module 7: Meaning and Structure of/in Verb Phrases

Module 7: Advanced Unit

Contents of Advanced Unit:

- Thematic roles

- Selectional restrictions

- Trees for each verb type

- Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 7, Advanced Unit

1. Thematic roles

Let’s go even further into thinking about how predicators (verbs) relate to their complement, specifically when we have verbs that take one, two, or three NP complements (e.g., intransitive, transitive, or ditransitive verbs). WHY do some verbs want one complement, while others want two or three? It all comes down to the meaning of a verb.

Each complement plays a particular role in the meaning of the verb–it’s involved somehow in the situation being described. In the field of semantics (the subfield of linguistics that studies meaning), we call this a complement’s thematic role. Is it doing an action? having an action done to it? experiencing a sensation? receiving something? causing a change of state? etc.

There is no single list of thematic roles accepted as standard among linguists, and different analyses use different categories. We will limit ourselves in this class to a list of the most-commonly-used thematic roles for English, and the ones that make most sense to me for our purposes. These are listed below, along with an example for each.

- Agent: making something happen, with sentience

- Beyoncé sang the song.

- Cause: causing something, without sentience

- The wind blew over the umbrella.

- Instrument: used to make something happen (typically non-sentient)

- The microphone recorded the sound.

- Theme: bearer of a state; undergoer of change of state or movement/transfer, not necessarily due to another participant

- The window broke.

- Patient: having something done to it by another participant (sometimes conflated with theme)

- My child broke the window.

- Recipient: receives something or receives benefit of something (sometimes called beneficiary/benefactive)

- The administration gave faculty raises.

- Experiencer: undergoes psychological/emotional/sensory experience

- My friend suffered.

(Note that you may also hear people call thematic roles “theta roles” or “semantic roles”; these refer to slightly different theoretic concepts but for our purposes they are the same.)

For each of the sentences above that have more than one complement, what is the thematic role of the other one?

the song: theme

the umbrella: patient

the sound: patient

my child: agent

the administration: agent

raises: theme

We say that each verb selects for one or more complements to fulfill its necessary thematic roles, in order to be interpretable. Different verbs select for different thematic roles that need to be fulfilled. And this is part of why we see those different structures across VPs. So whenever you hear someone talk about “different types of verbs,” they are most likely talking about a property of verbs that comes down to this: Which thematic role requirements does the verb’s meaning entail? Thematic role requirements are the meanings that underlie the structural complement requirements.

Let’s consider some familiar sentences:

Beyoncé birthed twins.

Taylor won her lawsuit.

Justin caused controversy.

The other Justin experienced a comeback.

What do you think are the thematic roles of each of these complements?

Beyoncé, Twins

Taylor, Lawsuit

Justin, Controversy

Justin, Comeback

I will remind you again of why some simplified descriptions of verbs as “action words,” of subjects as “things that do the action,” or of objects as “things that are acted upon,” are just that–highly simplified descriptions of what is actually a very complex set of meaning relations.

Thematic roles are about the underlying meaning of a proposition, i.e. sentence. Now let’s connect all of this to the surface structure we see of sentences.

The thematic role of a complement is not determined by its syntactic function (its position, function, and relationships within a grammatical sentence). Rather, these functions and roles can shift in alignment. That is, a single thematic role does not always manifest in the same syntactic function/position. And a single syntactic function/position may be occupied by a complement serving a different thematic role, depending on the verb! In other words, there is no one-to-one consistent alignment between thematic roles and syntactic functions.

Subject, for example, is an example of syntactic function. It is a position that a noun phrase can fill in a sentence. The subject could have any number of thematic roles though, depending on what the verb’s meaning is. Let’s understand a few sentences from the perspective of thematic roles and syntactic function:

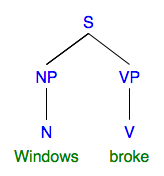

sentence: Windows broke.

thematic role of Windows: theme

syntactic function of Windows: subject

syntax tree:

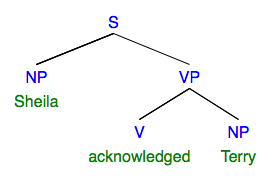

sentence: Sheila acknowledged Terry.

thematic role of Sheila: agent

thematic role of Terry: patient

syntactic function of Sheila: subject

syntactic function of Terry: direct object

syntax tree:

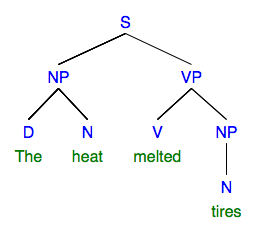

sentence: The heat melted tires.

thematic role of heat: cause

thematic role of tires: theme

syntactic function of The heat: subject

syntactic function of tires: direct object

syntax tree:

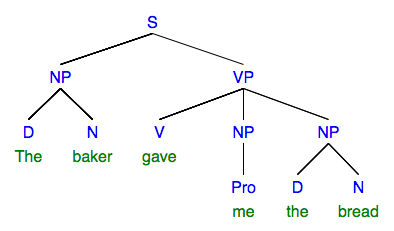

sentence: The baker gave me the bread.

thematic role of The baker: agent

thematic role of the bread: theme

thematic role of me: recipient

syntactic function of The baker: subject

syntactic function of the bread: direct object

syntactic function of me: indirect object

syntax tree:

The direct object, as an internal complement, is centrally involved in the meaning of a transitive or ditransitive verb. A direct object is typically the patient or theme (but not always). See the similarities between these three direct objects:

Sheila acknowledged Terry.

The heat melted tires.

The baker gave me the bread.

Terry is being acknowledged. Tires are being melted. The bread is being given.

The indirect object is also involved in the meaning of a ditransitive verb, typically as a recipient or beneficiary. Each of these sentences has a direct and indirect object; I’ve italicized the indirect object:

The baker made me the bread.

She sent the company an email.

They offered her a refund.

It’s the bread that’s being made, the email that’s being sent, and the refund that’s being offered. These are the direct objects. In thematic roles, they are themes or patients.

The other arguments—me, the company, her—are the indirect objects. In thematic roles, they are recipients of the items being transferred.

Notice that ditransitive sentences can be rewritten with the direct object appearing to be more central to the verb, and the indirect object displaced to a prepositional phrase:

The baker made the bread for me.

She sent an email to the company.

They offered a refund to her.

This is called the ditransitive or dative alternation: in English, we can alternate the expression of ditransitive verbs between structures where the direct object is first, and structures where the indirect object is first.

The baker made me the bread.

The baker made the bread for me.

She sent the company an email.

She sent an email to the company.

They offered her a refund.

They offered a refund to her.

(Historically, the argument occurring in the prepositional phrase took dative case-marking; English doesn’t have separate dative case-marking anymore.)

There are many such alternations like this in English, actually:

They spread butter on the bread.

They spread the bread with butter.

They drained the swamp of bankers.

They drained bankers from the swamp.

Lauren conversed with Warren.

Lauren and Warren conversed.

Lava is oozing from the volcano.

The volcano is oozing with lava.

(For more verb alternations like this, see Levin (1993).)

These examples highlight that there is no one-to-one alignment between thematic roles and syntactic functions. Subjects are often agents, but they can also be themes, patients, causes, etc. Direct objects are often patients, but they can also be experiencers, themes, recipients, etc. Here is a pair of related verbs that more or less mean the same thing, but reverse the relationship between syntactic function and thematic role:

Warren fears the dragon.

The dragon frightens Warren.

Fear wants an experiencer as subject and a theme as direct object. Frighten wants an agent, or perhaps cause (if it’s non-sentient), as subject and experiencer as direct object. Can you think of other verbs like this? (See more in David Pesetsky, Zero Syntax: Experiencers and Cascades, ch. 2, p. 18)

Thematic roles can also help explain why some sentences are nonsensical, even if they seem grammatical on the surface.

The email sent her the company.

Tires melted the heat.

Bananas suffered.

Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.

Each of these is structurally identical to a sentence we have already seen, but the meanings don’t work. Specifically, the nouns I’ve placed into the argument slots don’t match the thematic role requirements of the verbs.

Send requires a subject that is an agent, whereas email doesn’t have agency. Heat cannot be a theme for Melt, since heat cannot be melted. And Tire cannot be an agent for melt–tires cannot melt things (unless we are talking about fantastical circumstances). Since bananas do not experience feelings like suffering (except in storybooks), Banana is not a good agent for Suffer. And ideas cannot experience sleep.

2. Selectional restrictions

The way you store verbs in your mental lexicon, they come equipped with these specifications for complements and thematic roles. The fancy word for this is their selectional restrictions. Many verbs have different “versions,” or what we would call different “lexical entries,” such that they have more than one possible set of arguments. Break is a good example of this. Consider the following:

Windows broke.

My child broke the windows.

We could say that the first sense of Break selects for one complement—a theme—while the second sense of Break selects for two complements—an agent and a patient. The first is intransitive; the second is transitive. It’s actually difficult in English to find a verb that can’t under at least some circumstances be transitive: even Cough, which I have been using a prototypical transitive verb:

I coughed.

I coughed a disgusting cough.

(This is kind of like how it’s tough to find an adjective in English that truly can’t be graded, if you try hard enough to come up with a specific context!)

And there are verbs that have intransitive, transitive, and ditransitive senses:

She passed.

She passed the cupcakes.

She passed Larry the cupcakes.

I am reading.

I am reading a book.

I am reading my son a book.

Here’s an example of selectional requirements being violated to interesting effect. My son, when he was around 5, said the following sentence after playing a game with his dad:

What he meant would be expressed in adult English as:

WIN and DEFEAT have very similar meanings in the context of a game–they involve someone performing at a higher level than someone else, or producing a better outcome than someone else. And, they can both be transitive verbs! My son could say, without controversy:

“I winned the game!”

Why can “Daddy” be a direct object for WIN, but not DEFEAT? These verbs have different selectional restrictions for what the thematic roles are for the subject and object. WIN selects for an experiencer as a subject and a theme as an object. We might say that DEFEAT selects for an agent as a subject and a experiencer as an object.

Much of what you find in “poetic language” is playing around with a verb’s selectional restrictions, and what kinds of complements it typically takes. You find this in song lyrics, too!

So, now we have a typology of 5 basic verb and clause types. You will sometimes find VPs that have different things going on than this, and verbs that don’t fit into these categories–so it goes. But this list is pretty good to account for the majority of English clauses.

I’ve tried to provide some ways of understanding how these different structures in VPs derive from different meanings expressed by different verbs. To explore this we talked about predicators and complements; and, we talked about thematic roles as selectional restrictions on a verb’s complements. I hope this brings a level of technical understanding and description to some things you have probably noticed about language before, but didn’t have the metalanguage to talk about!

Remember that adverbials don’t change the type of verb something is. Neither do the presence of auxiliary verbs, and neither does the inflection of the verb.

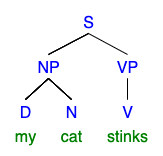

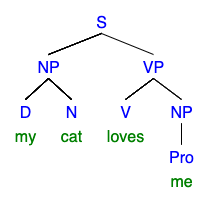

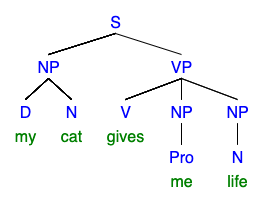

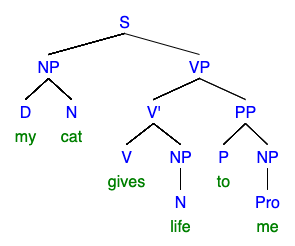

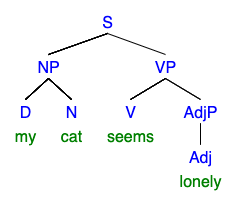

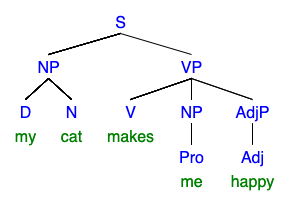

All of that said, here are simple trees for each of the 5 basic verb types. Refer back to these when needed!

- Intransitive: no internal complement; S-V

2. Transitive: direct object; S-V-O

3. Ditransitive: indirect object + direct object; S-V-IO-DO

3a. Dative alternation re-write of ditransitives: S-V-DO-PP

4. Complex-intransitive: predicative complement; S-V-PC

5. Complex-transitive: direct object + predicative complement; S-V-DO-PC

4. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 7, Advanced Unit

Complete before moving on to the next unit!

[[in progress; check back later!]]