Module 8: Grammatical Meanings and their Expression

Module 8: Basic Unit

GRAMMATICAL MEANINGS AND THEIR EXPRESSION

Contents of Basic Unit:

1. Refresher on grammatical meaning

In this unit, we will explore the major categories of grammatical meaning expressed in English clauses. As we talked about in Module 2, we can think about two types of meaning expressed in language: lexical meaning and grammatical meaning. Here were our basic definitions:

Lexical v. Grammatical Meaning

lexical meaning: what the word/morpheme refers to

grammatical meaning: type of meaning the word/morpheme conveys relative to other words in a phrase or sentence

Now that we have a better understanding of the kinds of relationships words and phrases have in a clause, we are positioned to more rigorously talk about the grammatical meanings that are at play in those relationships. We’ll start with some of the simpler categories we’ve already discussed, and then deal with more complex ones.

Grammatical meaning is often—but not entirely—expressed through the inflectional morphemes. Here is a reminder on those morphemes, which will be critical to our discussion:

| Morpheme | Grammatical meaning / what we’ll call the inflection | Attaches to | Example |

| {-s} or {-es} | plural | nouns | cats; pianos; boxes |

| {-’s} or {-s’} | possessive | nouns | cat’s; piano’s; plants’ |

| {-s} | third person singular present tense | verbs | kicks; eats; wants |

| {-ed} | past tense | verbs | kicked; looked; wanted |

| {-ed} or {-en} | past participle | verbs | kicked; eaten; wanted |

| {-ing} | present participle | verbs | kicking; eating; wanting |

| {-er} | comparative | adjectives/adverbs | happier; sadder; slower |

| {-est} | superlative | adjectives/adverbs | happiest; saddest; slowest |

2. Number

Number is a fairly simple category of grammatical meaning in English. It applies to nouns and noun phrases. We have singular nouns and plural nouns; the singular form of a noun is its “base” form, and the regular plural form includes the {-s} ending. Of course we have “irregular” plurals, too, as we’ve discussed.

One interesting note with regards to number is that the head of a noun phrase dictates the number of the whole noun phrase: an NP with a singular head will be treated syntactically as singular, while an NP with a plural head will be treated syntactically as plural. This is regardless of what else is in the NP. Consider the following NPs:

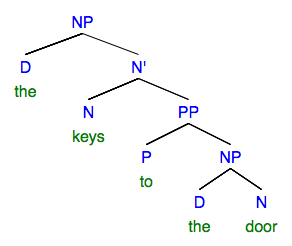

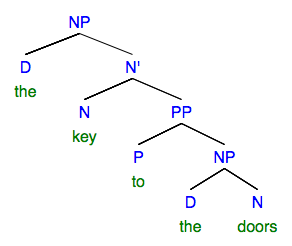

1a) the key to the door

1b) the key to the doors

2a) the keys to the doors

2b) the keys to the door

In 1a and 1b, the head is key, and the entire NP is singular—even though within the prepositional phrase, doors is plural in 1b. In 2a and 2b, the head is keys, and the entire NP is plural—even though within the prepositional phrase, door is singular in 2b. It is the head of the phrase that carries its number! So grammatical sentences would be:

1a) The key to the door is missing.

1b) The key to the doors is missing.

2a) The keys to the doors are missing.

2b) The keys to the door are missing.

We see the number of the NP head reflected in the verb inflection: English has subject-verb agreement. In (1a) and (1b), the verb inflection is the third-person singular: is. That’s because the head of the NP in both cases is singular key. In (2a) and (2b), the verb inflection is the third person plural: are. That’s because the head of the NP is keys. More on subject-verb agreement below.

Remember what the structure of these NPs would be:

This highlights again the importance of understanding relationships between words as being hierarchical: the PPs are embedded within the larger NP headed by key/keys. Any NP within that PP doesn’t affect the grammatical properties (in this case, number) of the whole NP.

3. Person

Person is a category of meaning that has to do with who is talking (or writing) relative to who they are talking (or writing) about:

Person distinctions

- First person: the speaker

- Second person: the addressee

- Third person: neither the speaker nor the addressee

We see person distinctions very clearly in our pronoun inflections:

| First person singular | Second person singular | Third person singular |

| I | you | he/she/it |

This is only a small fraction of our personal pronouns, though! Number is also reflected in our pronoun inflections; each of the singular pronouns above also has a plural counterpart:

| First person plural | Second person plural | Third person plural |

| we | you/y’all/youse/yinz/you guys | they |

This is still only a fraction of our personal pronouns, though! There is a third category represented in our pronoun inflections, called case—we’ll get to that in a minute.

Since our pronouns inflect for both number and person, you’d think our nouns would too, but in English, nouns don’t inflect for person. However, person differences do affect another part of the system—our verbs! Read on…

4. Subject-verb agreement

English, like many languages, has what is called subject-verb agreement (also sometimes called concord). This grammatical relationship is expressed on the verb, but it reflects properties of the subject: different subjects trigger different verb inflections.

In English, subject-verb agreement involves the grammatical categories of person, number, and tense. Subject-verb agreement is why you have a different verb inflection in 3a and 3b:

(3a) The key sits on the table.

(3b) The keys sit on the table.

In fact, for regular verbs in Standard English, the third-person singular {-s} form is the only verb inflection specific to subject-verb agreement. It is only when the clause is in present tense, and when the subject is third-person and singular that it appears. Consider the following paradigm:

singular

first person – I need the keys.

second person – You need the keys.

third person – She needs the keys.

plural

first person – We need the keys.

second person – Y’all need the keys.

third person – They need the keys.

The ONLY subject type that takes an inflection which, on the surface, differs from the uninflected verb form is third-person singular. English used to have way more verb inflections than this, but as goes history, so have gone our inflections.

4a. Agreement and BE

Remnants of a richer subject-verb agreement paradigm are still found with that most irregular of irregular verbs, BE. Unlike regular verbs, BE inflects to show distinctions in person, number, and tense across these different combinations of subjects. The table below summarizes:

| person | number | present tense | past tense |

| first person | singular | am | was |

| plural | are | were | |

| second person | singular | are | were |

| plural | are | were | |

| third person | singular | is | was |

| plural | are | were |

As you can see though, even with BE, the paradigm is imbalanced. There are 12 possible combinations of person, number, and tense, yet we have only 5 distinct inflected forms of BE.

4b. Agreement and dialect variation

It’s important to note that subject-verb agreement is a big area of dialect differences between English varieties. To give just one example: African American English permits the entire present-tense paradigm to be leveled, such that the verb occurs in the base (uninflected) form regardless of the number/person of the subject. Consider, from Beyoncé:

There are other interesting differences, too. In most vernacular English dialects, the auxiliary verb DO can appear in its negated form without inflection, regardless of subject:

4a) I don’t sing that song.

4b) You don’t sing that song.

4c) He don’t sing that song.

While Standard English would use doesn’t in (4c), this use of invariant don’t is prevalent in English dialects worldwide. Here it is in the lyrics of Justin Bieber:

And still other dialects use an {-s} verb inflection for all subjects—plural and singular—but only under certain circumstances! Consider these attested examples from Northern English dialects, from the work of Lukas Pietsch:

The birds sings

They sing and dances

Them’s the men that does their work best

This somewhat complicated pattern is called the Northern Subject Rule.

4c. Agreement and finiteness

Subject-verb agreement is also a crucial factor in the distinction between clauses and sentences. Every complete sentence will have at least one verb that we call finite. In the usual case of declarative sentences, a finite verb is one that is inflected for both tense and subject-verb agreement. Consider these:

5a) The dogs eat their food.

5b) The dog eats its food.

5c) That candle smells delicious.

5d) These candles smell delicious.

These are all complete sentences, right? But let’s see what happens when we swap these verbs with a present participle inflection:

6a) *The dogs eating their food

6b) *The dog eating its food

6c) *That candle smelling delicious

6d) *Candles smelling delicious

The list in (6) is ungrammatical—what’s going on? There is still a verb in the clause, expressing semantic meaning. We could still even say that these verbs have their argument needs / thematic roles fulfilled. In other words, the referential meaning seems solid.

What’s wrong here is something purely syntactic: these verbs lack the inflection that carries tense, person, and number information. That is, they don’t carry tense information, and they lack subject-verb agreement. Look at how adding an auxiliary verb fixes this, as long as the verb is inflected for agreement:

6a) The dogs were eating their food

6b) The dog was eating its food

6c) That candle is smelling delicious

6d) Candles are smelling delicious

(If you think 6c and 6d sound a little weird, you’ve just discovered something about different predicates and English aspect! Wait for the advanced unit!)

In any clause, we call the verb that is inflected for tense and subject-verb agreement a finite verb. Modal verbs are also inherently finite—we’ll see that later on. In contrast, we call a verb that is not inflected for tense and subject-verb agreement a nonfinite verb. Present participles, past participles, and infinitive verb forms are always nonfinite.

Key Takeaways

Finite verb forms: present tense; past tense; modal verbs (can, could, etc.)

Nonfinite verb forms: present participle; past participle; infinitive (to go, to eat, etc.)

And here is one key difference between sentences and clauses: clauses can be finite or nonfinite, but sentences are always finite. This can be summarized as:

Finiteness

- Every sentence must have at least one finite clause.

- A finite clause includes a finite verb.

We will explore much more of this in the next module!

5. Gender

Grammatical meanings help us understand all the different inflections of pronouns we have, whereas our inflections for full nouns are impoverished by comparison. The final category of grammatical meaning that is relevant to understanding pronoun inflections is gender.

As with other categories of grammatical meaning, the status of gender in English has changed over time. Many languages—including German, Russian, and Romance languages like French, Spanish, and Italian—categorize nouns according to what’s called grammatical gender: a system of classifying nouns for agreement purposes. For instance, every German noun is either masculine, feminine, or neuter—those are German’s three gender categories. (Check out the array of grammatical gender categories across languages—from zero to more than five.)

These grammatical gender categories sometimes map on to what I will call social gender (though it is traditionally called natural gender)–gender identity as felt and enacted in society. But once you start looking at examples it’s clear that the mapping between grammatical and social gender is not at all a regular one. (Here’s a quick read on this issue.) Witness some German nouns and their genders:

feminine

die Fenster (‘window’)

die Frau (‘woman’)

die Bücherei (‘library’)

masculine

der Tag (‘day’)

der Norden (‘north’)

der Mann (‘man’)

neuter

das Mädchen (‘girl’)

das Museum (‘museum’)

das Gold (‘gold’)

(Note that the definite determiner preceding each noun is different—it agrees with the gender of the noun itself. This is something English used to have too.)

As you see from this short list, there is no reason to consider something like “north” to be masculine but something like “library” to be feminine—these are grammatical categories and do not line up neatly with social ideas about “gender.” (That said, there is evidence that speakers associate natural/social gender with grammatical gender at a pretty deep level. Also, are you wondering whether any of this has an effect on gender equity? Have another linguistics article!).

But English doesn’t have grammatical gender on its nouns anymore. Now, English only expresses gender differences in the sense of what is typically called natural or social gender (to contrast with grammatical gender). And once again, this marking only shows up in our pronoun system—and only in third person singular pronouns, at that: he/she/they/his/her/hers/theirs.

This is why pronouns, such small little words!, are such a “hot” topic in conversations about sexism, as well as diversity and inclusion. Because pronouns encode gender, they have long been recognized as an important component of nonsexist language, and they are increasingly understood as important to how we explicitly enact, acknowledge, and include a spectrum of gender identities in our social world.

Interestingly, languages typically have third-person gender distinctions, but first- and second-person gendered pronouns are rarer, though Japanese arguably has both, and Hebrew has gendered second-person pronouns. Conversely, there are some English varieties—mostly contact languages, pidgins and creoles—that don’t have a distinction in third-person either.

But the majority of English varieties use third-person singular pronouns in a way that reflects a) the social gender of the referent, and b) the social gender of the pronoun’s antecedent in a sentence. You may be familiar with one traditional prescriptive rule that relates to pronouns: that the only third-person singular pronouns that can refer to humans are the masculine he/him/his and the feminine she/her/hers. We do have a gender-“neutral” pronoun it/its, but we cannot refer to a human as it. (Technically, this is a difference in another grammatical meaning known as animacy.)

It has now become common for they/their to be used in this “gender-neutral” way, though people have introduced other new pronouns into the paradigm as well to accomplish this same purpose, such as ze and per. (This Wikipedia discussion on third-person pronouns is simply fascinating.)

Some people still seem concerned that “singular they” will lead to the downfall of English, but this is just not true. Pronouns have been changing throughout the history of English, and they will continue to do so. And actually, they has been used as a singular, neuter pronoun for centuries. One of my former advisors at Michigan, Anne Curzan, is an expert on this topic and has a very good explanation of it.

For more on the linguistics of they, I invite you to check out the research and resources from linguist Kirby Conrod, who has advanced the syntactic and sociolinguistic study of this topic in recent years!

6. Degree

Degree came up in our discussion of inflectional morphemes, which can grammatically encode the position of a quality on a scale from “less so” to “more so.” We have two inflectional categories of degree in English: the comparative, “more than,” and the superlative, “the most of.” We know already that these are the {-er} morpheme for the comparative and the {-est} morpheme for the superlative. Here are some examples:

ADJ COMPARATIVE SUPERLATIVE

fast faster fastest

good better best

blue bluer bluest

Some adjectives/adverbs seem to resist degree comparisons, though some people argue that it’s just a matter of finding the right context in order to make any adjective/adverb “gradable” (subject to degree).

Aside from semantics, there are also phonological patterns in English dictating when the degree morphemes are used, versus the marking of degree in other ways—by the addition of other adverbs, specifically. So we don’t find the following inflected forms:

ADJ COMPARATIVE SUPERLATIVE

peaceful peacefuler peacefulest

elfish elfisher elfishest

integrated integrateder integratedest

ridiculous ridiculouser ridiculousest

educational educationaler educationalist

yellow yellower yellowest (?)

Can you identify some elements of word structure that make these forms unlikely, as compared to the following:

ADJ COMPARATIVE SUPERLATIVE

glossy glossier glossiest

red redder reddest

funny funnier funniest

great greater greatest

soft softer softest

pretty prettier prettiest

We worked on examples like this in class earlier in the semester… can you remember the basic preferences for English speakers?

7. Case

Case is a grammatical meaning that marks the syntactic role of a noun phrase in a sentence. Different languages mark different cases for different syntactic roles. Old English had an abundant case system (more like modern-day German, but not as complex as Russian!). Modern-day English, though, has very limited case-marking; only three categories of case are distinguished:

Case Distinctions

- nominative case: marks the subject (sometimes called subjective or just subject case)

- accusative case: marks the object of a verb or preposition (sometimes called objective or just object case)

- genitive case: marks a possessor (sometimes called possessive case)

Moreover, nominative and accusative case distinctions are not marked on regular nouns, only on pronouns. In (7) below, the nouns DOG and CAT remain in the same form regardless of whether they are functioning as subject or object:

7a) The dog saw the cat.

7b) The cat saw the dog.

Pronouns, on the other hand, exhibit case inflections for subject versus object:

8a) She saw him.

8b) He saw her.

8c) *Him saw she.

8d) *Her saw he.

Genitive case is still reflected on both pronouns and nouns in Standard English. (In African American English, there is often no genitive ending on nouns, e.g. “the dog tail”; read about it here). This is the “possessive” {-s} inflection on nouns, and the my/your/her/his/its/their forms of pronouns:

9a) The dog’s tail wagged.

9b) The dog chased the cat’s tail.

9c) Her tail wagged.

9d) The dog chased its tail.

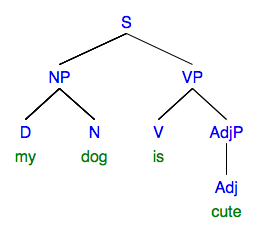

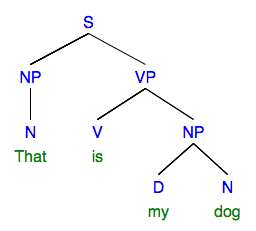

Note that possessive nouns/pronouns function internally to a larger NP, and that larger NP could be functioning in any of the ordinary roles of an NP. In other words, the genitive inflection does not differ depending on whether the NP it is a part of functions nominatively or accusatively! Examples:

Here, “my dog” is my dog in both subject and complement (predicate) position. The form of the pronoun my does not change.

Here are the genitive/possessive pronoun inflections:

| First person | Second person | Third person | |

| singular | my/mine | your/yours | his/her/hers/its |

| plural | our/ours | your/yours | their/theirs |

(What’s the difference in function of my v. mine or your v. yours?)

By the way, case inflections mark the function of an NP in a clause, but case markings are not limited to nouns/pronouns—in Old English, determiners and adjectives also inflected to “agree” in case with the nouns they modified. (Something German still does.) Just another example of how grammatical meanings frequently operate at the phrase level, not just the word level.

8. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 8, Basic Unit

Complete before moving on to the next unit!