Module 3: Word and Phrase Categories

Module 3: Basic Unit

WORD AND PHRASE CATEGORIES

Contents of Basic Unit:

- Introduction: Categories of words

- Lexical categories

- Grammatical categories

- Phrases

- Phrase types

- Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 3, Basic Unit

1. Introduction: Categories of words

As with morphemes, words can be divided into two broad categories based on the kind of meaning they carry. Lexical categories carry the primary referential meaning of a sentence. These are sometimes called content words. Grammatical categories are function words that express relationships between other words, create internal structure within a sentence, or specify the reference of lexical category words.

Lexical and Grammatical Categories

- Lexical categories are verbs, nouns, adjectives, and adverbs.

- Grammatical categories are everything else: determiners, pronouns, prepositions, auxiliary verbs, conjunctions, and subordinators/complementizers.

In this module we will give basic definitions of these word categories, but you will get a better feel for them as we work with sentence structure. These are not absolute categorizations: different grammars, textbooks, and teachers will put some words in different places (for instance, many people consider pronouns and prepositions to be lexical categories). I note this just to prepare you that you may find people using slightly different systems of categorization than we will use, and that is fine. We are all just humans trying to understand language!

2. Lexical categories

I’ll start with a food analogy. Think of a burger. Lexical categories are the key ingredients in defining a burger as a burger. What is the one required part of a burger? The patty. You can order a “burger” without the bun (like someone avoiding carbs), and you may just end up with a patty and condiments. But if you ask for a “burger” without the patty, you are just getting the bun, which is not actually a burger at all.

The patty in a burger is like the verb in a sentence. Every sentence in English contains at least one verb. Therefore, every English sentence contains at least one lexical category word. And the smallest possible English sentences contain just this one category, a verb:

Go!

Dance!

Play!

Eat!

These words imply someone doing the action—you—and are equivalent in meaning to the following:

You go!

You dance!

You play!

You eat!

It is impossible for me to utter “Go!” and have you interpret me as meaning “That person over there should go.” This highlights one fact about sentences: we interpret there to be a subject, or something that is the actor or topic of the sentence, even when it is not explicitly pronounced.

Therefore, not only does every sentence have at least a verb, but most sentences also contain at least one noun. Consider the following two-word sentences:

Birds chirp.

Mushrooms stink.

Sheep baa.

Syntax rules.

Rock’n’roll lives.

If a verb is like the patty, a noun is like the bun: nearly all sentences will have one. You can have a bun-less burger with just a patty; it’s rare, but you can order it. Likewise, you can have a noun-less “sentence” with just a verb—it serves a specific expression of meaning, but is still a sentence.

In contrast, the nouns standing alone in the below examples are not “sentences”:

Syntax

Sheep

Birds

Mushrooms

Rock’n’roll

These nouns are just nouns, not sentences—like buns without a patty.

So a verb is necessary for a sentence, and most sentences also have a noun. What about everything else?

What if you wanted to add something to your patty, to increase its deliciousness? Maybe blue cheese? That would be like an adverb. Blue cheese modifies the patty; an adverb modifies a verb. And what about adding mustard to your bun? That would be like an adjective. Mustard modifies the bun; an adjective modifies a noun. In other words: the patty and the bun are still the most essential parts of the burger. The other categories of items are modifying either the patty or the bun. You can’t have a burger with just blue cheese and mustard; you can’t have a sentence with just adjectives and adverbs.

Let’s use these lexical categories to build the sentence we saw at the end of the last module. Start with a verb:

Add a noun:

Ballerinas dance.

Add an adverb, which modifies the verb:

Ballerinas dance beautifully.

Add an adjective, which modifies the noun:

Beautiful ballerinas dance beautifully.

All together, we have the four lexical categories:

Beautiful ballerinas dance beautifully.

ADJECTIVE NOUN VERB ADVERB

The verb is essential; there would be no sentence without it. The noun is the subject, doing the dancing. The adverb tells how the ballerinas dance—it modifies the verb. And the adjective gives us a property of the ballerinas—it modifies the noun.

Aside from understanding their functions relative to each other, we can notice patterns that categories of words tend to exhibit in terms of a) their morphology, and b) their syntactic behavior. For instance, most nouns tend to act the same way when it comes to inflectional and derivational morphology; and, they tend to act the same way in sentences. Consider the following list of sentences, with their lexical category words; then consider why the second list is ungrammatical.

Beautiful ballerinas dance beautifully.

Ugly ducklings swim awkwardly.

Genuine diamonds glisten appealingly.

False lashes attach effortlessly.

*Beautiful dance beautifully ballerinas.

*Ugly swim awkwardly ducklings.

*Genuine glisten appealingly diamonds.

*False attach effortlessly lashes.

Explain the Ungrammaticality Activity

We will explore in detail the morphological and syntactic patterns of different lexical categories in Modules 5-7.

You can see from the above that a very important relationship often formed between words is one of modification: adding information to a word, thereby changing its lexical meaning. As we have already seen, one major function of adjectives is to modify nouns:

beautiful ballerinas

ugly ducklings

genuine diamonds

false lashes

Put casually, adjectival modification adds information that answers the question, “What kind?”

Ballerinas! What kind? Beautiful ones.

Ducklings! What kind? Ugly ones.

Similarly, one major function of adverbs is to modify verbs:

dance beautifully

swim awkwardly

glisten appealingly

attach effortlessly

Adverbial modification of verbs usually adds information that answers a wh-question: “How/Where/When/Why?”

They danced. How? Beautifully.

They swam. Where? There.

They glisten. When? Always.

Adverbs can also modify adjectives or other adverbs:

extremely beautiful ballerinas

shockingly ugly ducklings

dance incredibly beautifully

swim very awkwardly

Usually this modification is about heightening or lowering the degree of the quality being attributed by the adjective, and hence we call these degree adverbs.

How beautiful? Extremely.

How beautifully? Incredibly.

Consider the difference in meaning between the adverbs surprisingly and really below:

It was surprisingly beautifully painted.

It was really beautifully painted.

While suprisingly carries content–the beautiful way in which the thing was painted was surprising–really doesn’t quite carry content in the same way; all I’m saying is that the beautiful way in which the thing was painted is to a heightened degree. Do you think degree adverbs should be classified as content, or function words?

3. Grammatical Categories

A modification role is also the function of many of the grammatical categories of words, which we overview here.

Determiners serve to restrict the reference of a noun or noun phrase:

duckling

a duckling

the duckling

these ducklings

five ducklings

my duckling

What information is added/changed by the addition of a, the, these, or my?

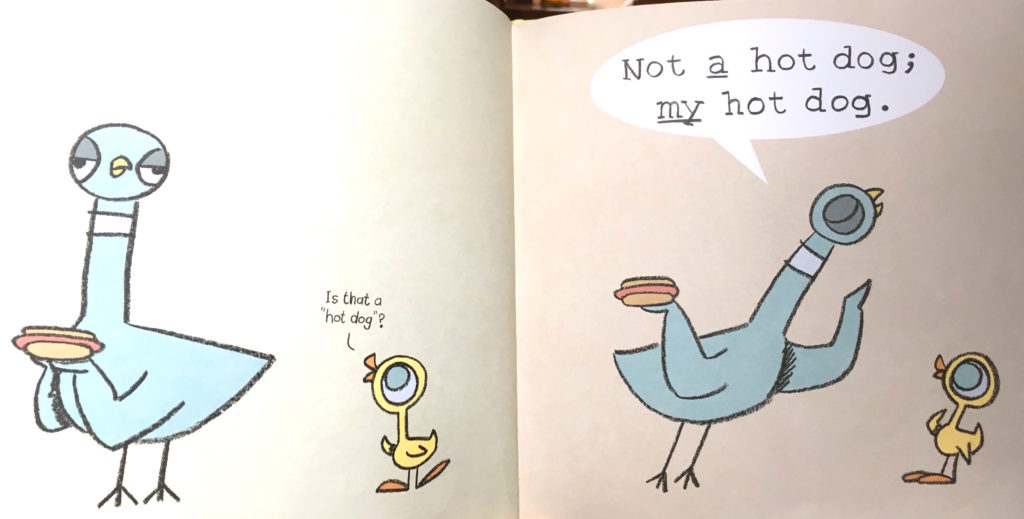

Consider the following pages from a popular children’s book, The Pigeon Finds a Hot Dog, by Mo Willems:

What is the difference between a hot dog and my hot dog? That’s the kind of grammatical meaning contributed by determiners. Try to identify determiners in the activity below.

In the above poem, my and that are examples of pronouns being used as determiners, but many pronouns also occur independently. You have probably heard of pronouns as “words that substitute for nouns,” but we’ll see that this isn’t quite right. Nonetheless, pronouns do function similarly to nouns in sentences—with the difference being that their reference is not fixed, but dependent on context (we call this contextual dependency deixis; pronouns are deictic elements of language).

Mine is awesome.

I am awesome.

She is awesome.

You are awesome.

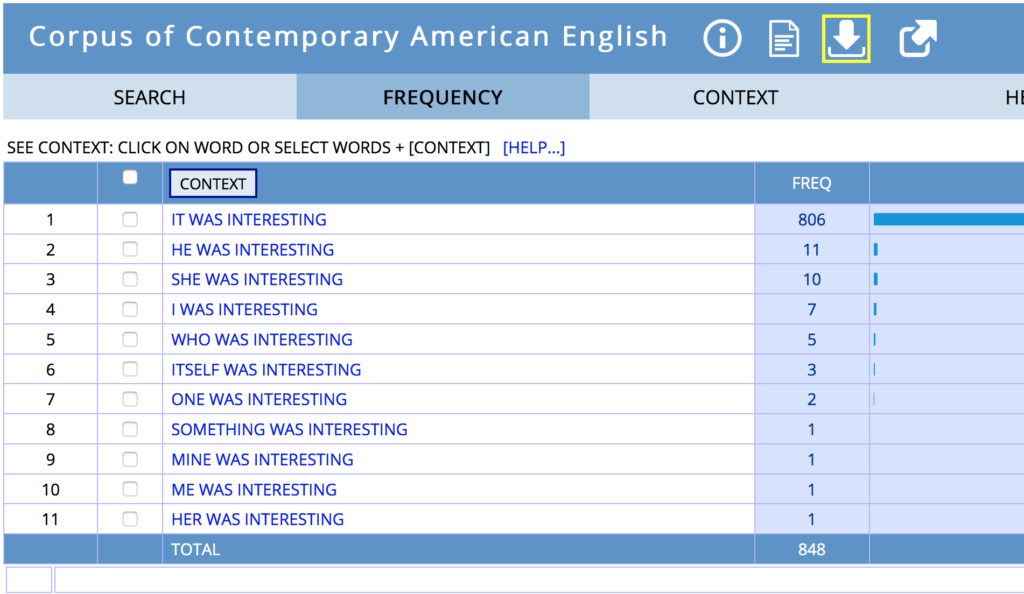

There are lots of different kinds of pronouns, with varying properties. I did a search in the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) for [PRONOUN was interesting], and these are the results I got:

Do some of these seem to have more in common than others? How might you divide them into sub-categories based on their meanings or other properties?

Moving on to prepositions! Prepositions introduce nouns or noun phrases into a larger phrase or sentence, nearly always in order to modify another unit. In the examples below, prepositions are introducing phrases that modify nouns:

ducklings in the pond

ballerinas from the company

diamonds on your timepiece

tigers at the zoo

Prepositions are typically “little” words, and they often carry a spatial meaning. Did you ever hear that a preposition is “what a plane can do to a cloud” or “what a mouse can do to a clock”? The idea is on the right track, since many prepositions carry a spatial meaning:

the plane flew through the cloud

the plane flew over the cloud

the mouse ran toward the clock

the mouse ran under the clock

But many prepositions do not express a spatial relationship at all:

the book by J.K. Rowling

the ice cream from Jeni’s

the present for his birthday

And how would you characterize the function of the prepositions in the below sentences? Note that the phrases they introduce all modify verbs, and are in this sense are…what’s the word for things that modify verbs?…adverbial!

The ballerinas dance in companies.

Ducklings swim in ponds.

The diamonds flash before my eyes.

The lashes attach over the eyelids.

Other grammatical word categories do not modify, but connect elements in another way. Two main such connective relationships are coordination and subordination.

Conjunctions form a coordinating function: they join together elements that carry equal status in a sentence or phrase. They are therefore often called coordinators (and I may sometimes use these term interchangeably). The primary conjunctions you might think of are and, but, and or. (See how I just used one to list items of the same type!)

In each of these examples of coordination, you can reverse the order of the items and see little effect on the meaning of the sentence:

I made cookies and tea.

I feel cautious but optimistic.

You may run or walk the race.

In contrast, subordinators—which later we will call complementizers—connect elements that do not have equal status in a sentence. Classic subordinators are words like because, if, although, and while. Later we will see that one of the main subordinators we use in English is actually that. Relative pronouns who, whose, and which also function to introduce subordinate elements.

I want ice cream because it is hot outside.

I’ll eat ice cream if it’s over 70 degrees.

She ate ice cream even though it was snowing.

Unlike with conjunctions, trying to change the order of connected elements here leads to complete changes in meaning, and in some cases even ungrammaticality:

It is hot outside because I want ice cream.

*It’s over 70 degrees if I’ll eat ice cream.

It was snowing even though she ate ice cream.

The final grammatical category is auxiliary verbs. We will talk more about these in module 6, but you can start to recognize that verbs often occur in series, and work together to form complex grammatical meanings. The verbs highlighted below are auxiliaries.

We have been eating.

We were eating.

We could be eating.

We have eaten.

The pizza was eaten.

Students do like pizza.

4. Phrases

Below the level of a full sentence, words enter into relationships with each other, constituting units of meaning that are still smaller than a sentence. A phrase is a group of words that functions together as a unit within a larger unit of grammatical structure.

Keyword

phrase: group of words that functions together as a unit within a larger unit of grammatical structure

We already saw some examples above, where some types of words modify other types of words. Each of these highlighted units is a phrase consisting of the modifier and the word being modified:

Beautiful ballerinas dance beautifully.

Ugly ducklings swim awkwardly.

Genuine diamonds glisten appealingly.

False lashes attach effortlessly.

Each of these phrases consists of an adjective and a noun. Which word do you think is more important, the adjective or the noun? Is the unit “beautiful ballerinas” ultimately more nouny or more adjectivey? You probably have the intuition that it’s the ballerinas who are more important: indeed, the function of beautiful is to modify the noun. The noun is the main part. If you take the nouns away, the sentences become ungrammatical. Whereas if you take just the adjective away, the sentences are still grammatical.

*Beautiful dance beautifully.

*Ugly swim awkwardly.

*Genuine glisten appealingly.

*False attach effortlessly.

Ballerinas dance beautifully.

Ducklings swim awkwardly.

Diamonds glisten appealingly.

Lashes attach effortlessly.

Congratulations, you’ve just discovered that the head of this phrase is the noun, not the adjective! (more on this in a bit)

Here, I will introduce some different ways of thinking about phrases, then introduce the major phrase types we need to talk about in English grammar.

Ways to think about phrases…

- mental units

- structural units

- functional units

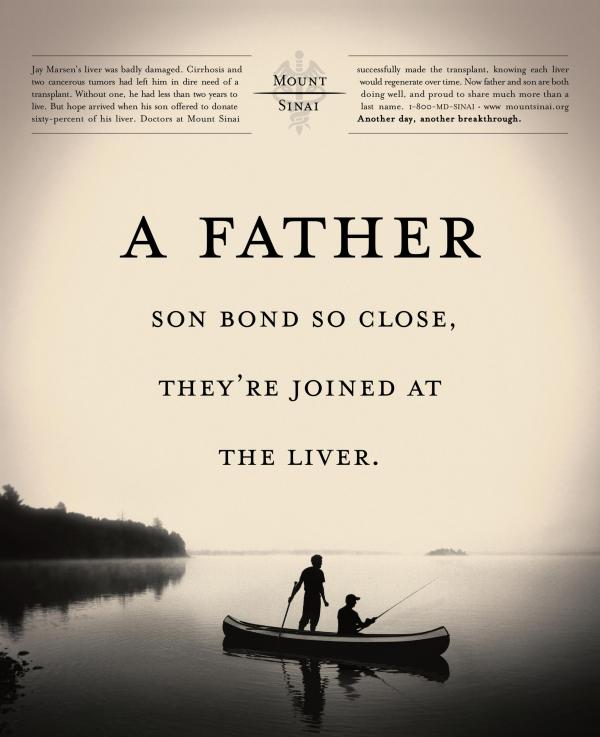

First, we can think of phrases as mental units. They capture some intuitions we have that within a sentence, some words are more closely related to each other than to others. Consider the following advertisement, which I came across in the New York Times Magazine some years ago.

Does this layout seem odd to read at all? The page layout makes it seem as though the following are meaningful units of grammar:

A father

son bond so close

they’re joined at

the liver

You don’t need technical terminology to understand that “son bond so close” is not a meaningful unit. How would you describe why these groupings of words are not phrases that function together? If you were going to reposition these words into units, it would probably be something like:

A father-son bond

so close

they’re joined

at the liver

This is the intuition we’re capturing with the notion of phrases: “a father-son bond” is a phrase, but “son bond so close” isn’t. Your brain doesn’t really know what to do with “son bond so close”—where would you put it in a sentence? Whereas you can probably think of lots of ways to use “A father-son bond” in a sentence:

A father-son bond is important.

They had a father-son-bond that was beautiful.

Theirs was a father-son-bond like no other.

They considered a father-son-bond to be a good thing.

Second, we can think of phrases as structural units. Consider the sequence of words:

What do you think the most important, most essential word is? I’d guess you said bond. Without bond, there would be no need for any of the other words. Now, consider the role of a. Do you think it relates more closely with father-son or bond? I would again guess that you said bond: a father-son is meaningless, whereas a bond means something clear. This shows that within the sequence of words, a father-son bond, there is some smaller structure of relationships between words. Namely, father-son modifies bond; then, a modifies or specifies father-son bond.

We can illustrate this kind of internal structure using bracketing notation, where brackets delineate meaningful groupings of words:

Phrases are therefore units that contain structure within them. They are also units that are part of larger structures—other phrases or sentences. Consider the sentence:

What is the structure of this sentence? Something is being said to be important. It’s not just bond, but the whole unit, a father-son bond. We can show this relationship with brackets again:

[A father-son bond] is important

Here is a slightly more embellished version of this sentence:

Where does extremely fit in here? It modifies important, and in fact forms a phrase with it. We can again use brackets to show this relationship:

A father-son bond is [extremely important]

So phrases are meaningful units of words that fit into the structure of a larger phrase or sentence. Here is bracket notation showing the internal structure of this sentence with both of our phrases:

Think about other sentences following this same pattern:

[Ugly ducklings] are [surprisingly common]

[Beautiful blue diamonds] are [exceedingly rare]

[The best ice cream flavor] is [summer corn with blackberry]

(Some of the bracketed phrases even have phrases within them!)

Third, we can think of phrases as functional units. Let’s go back to our sentence:

We’ve established that a father-son bond has structure, and also that it is part of a larger structure. What is its function in this sentence? It’s the entity to which “importance” is being ascribed; it’s also what the sentence is about—its topic, roughly speaking. We call this function the subject of the sentence. What are the subjects in each of these sentences?

[Ugly ducklings] are [surprisingly common]

[Beautiful blue diamonds] are [exceedingly rare]

[The best ice cream flavor] is [summer corn with blackberry]

Subject is a function that phrases can play within a sentence. Note that individual words can also be subjects:

[Corn] is awesome.

[Ducklings] are cool.

[Diamonds] are rare.

There are other functions that can be played by phrases. For instance, a prepositional phrase can modify a noun:

corn [with blackberry]

people [from Mars]

the books [in the library]

But individual words can also function as modifiers! Remember adjectives and adverbs?

beautiful people

colorful books

extremely important

fully capable

So, phrases—like words—can function in different roles within a sentence or phrase. Phrases are mental, structural, and functional units of meaning.

5. Phrase types

We will talk about five basic phrase types in English; we will add phrase types later as needed. The five phrase types correspond to the four lexical category words plus prepositions.

Major Phrase Types in English

- Verb Phrase

- Noun Phrase

- Adjective Phrase

- Adverb Phrase

- Prepositional Phrase

Each phrase type consists of at least a head—the word that corresponds to the phrase type, and which determines the nature of the meaning of the phrase, as well as the function of the phrase.

VP – Verb Phrase

VP’s have a verb as their head. Since every sentence has a verb, every sentence will have a verb phrase! More on this in module 4, and even more in Module 7! Examples of verb phrases:

walked

walked slowly

walked slowly around the block

walked the dog

She [walked the dog]

She [walked the dog slowly around the block]

NP – Noun Phrase

NP’s have a noun as their head, and function as nouns typically do. They can fulfill the subject role, for instance. Examples:

ducks

blue ducks

big blue ducks

the big blue ducks

[The big blue ducks] are beautiful

I love [the big blue ducks]

AdjP – Adjective Phrase

AdjP’s have an adjective as their head, and function as adjectives typically do. They can modify nouns, for instance. Examples:

beautiful

extremely beautiful

surprising

very surprising

very surprisingly good

[very surprisingly good] food

My meal was [good]

My meal was [very surprisingly good]

AdvP – Adverb Phrase

AdvP’s have an adverb as their head, and function as adverbs typically do. They can modify adjectives or verbs. Examples:

surprisingly

very surprisingly

gracefully

so gracefully

She danced [so gracefully]

She danced [so gracefully]

She did a [gracefully] simple dance

PP – Prepositional Phrase

PP’s have a preposition as their head, and function in various ways. See if you can pinpoint the function of some of the PPs below:

They flew [to the moon]

The girl [with the dragon tattoo] was fierce

She was certain [of the facts]

Notice that every PP above contains not just a preposition, but also a noun phrase. This NP is called the object of the preposition.

6. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 3, Basic Unit

Complete this before moving on to the next unit!