Module 4: Clauses

Module 4: Basic Unit

CLAUSES

Contents of Basic Unit:

1. Basic structure of clauses

In Module 3, we introduced the basic components of sentences. In this module we will explore the basic structure of sentences in a little more depth.

Even more specifically, we will talk about the structure of clauses. In some ways, a sentence is the same as a clause. But the relationship is sort of like one between a square and a rectangle: a square is a rectangle (four flat sides at 90-degree angles), but not every rectangle is a square (four sides of equal length). Likewise, a sentence is a clause, but not every clause is a sentence.

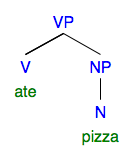

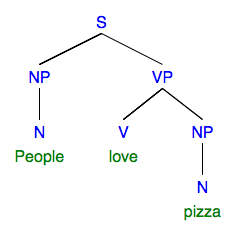

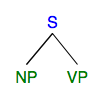

Clauses and sentences have roughly the same internal structure, but differ in terms of their relationship to other structures. We have learned that every sentence will have a verb, so every sentence will have a verb phrase. Let’s see a VP as a syntax tree diagram:

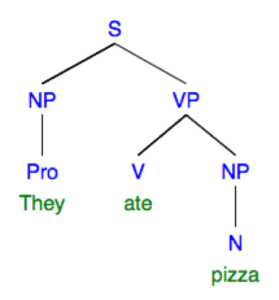

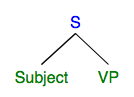

For this to be an independent sentence, what is missing? Recall our sentence functions from the last module…it’s a subject! We’ll place the subject—usually an NP, as we’ve seen—next to the VP, and say that these two units together form a sentence, an S.

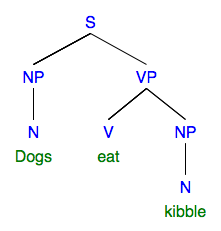

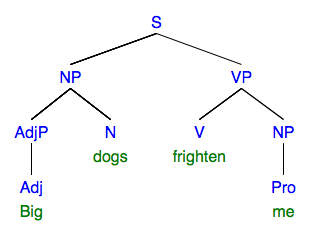

This is the internal structure of every sentence, and of every clause: a subject and a verb phrase. The subject function is typically (but not always) served by an NP. The verb phrase always consists of a verb, and usually other things too (we’ll get to that later). Here are examples of more sentences, using our tree diagrams.

Note how these sentences ALL share the same internal structure at the first level of hierarchy below the S. That is, they ALL have an NP and a VP. What constitutes those NPs and VPs is different (i.e. the internal structure of the NPs and VPs differs), but at the level just below the S, they are identical:

I will use the term sentence to refer to what is traditionally called an independent clause: a unit containing a subject and VP, and which “stands alone” to express a “complete thought.” That is, it does not depend on any larger unit for its meaning to be interpretable. All of the examples above are sentences:

They ate pizza.

People love pizza.

Dogs eat kibble.

Big dogs frighten me.

By contrast, I will use the term clause to refer to what is traditionally called a dependent clause. A clause has the same internal structure of a sentence, but is subordinate to some larger structure: it is dependent on another unit in order to be interpretable. Consider the following clauses:

because they ate pizza

that they ate pizza

while they ate pizza

What do you notice about these? You may notice that each of them seems to contain what looks like a sentence, but with an additional word. Consider:

because they ate pizza

that they ate pizza

while they ate pizza

They’re all the same! Yes! This is an example of a clause: there is a sentence—something with a subject (they) and a predicate (ate pizza)–but the “sentence” does not stand on its own. It has to be interpreted relative to a larger unit, such as…

They were full because they ate pizza

They could not believe that they ate pizza

They drank soda while they ate pizza

The unit they ate pizza contains a subject and a VP, but there is also more…and the bigger unit cannot stand on its own, so we won’t call it a sentence. This is what we use the term clause for: a unit with the same internal structure as a sentence, but that does not stand on its own.

We will explore clauses more later on; for now we will focus on sentences. But just keep in mind as we discuss, that all of the internal structural properties of sentences also apply to clauses.

2. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 4, Basic Unit

Complete before moving on to the next unit!