Module 5: Nouns, Adjectives, and Related Stuff

Module 5: Basic Unit

NOUNS, ADJECTIVES, AND RELATED STUFF

Contents of Basic Unit:

- Sub-categories of nouns

- Determiners

- Adjectives

- Prepositional Phrases

- Conjunctions

- Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 5, Basic Unit

1. Sub-categories of nouns

By now, you should feel comfortable with the basics of what a noun is. In this module we’ll explore some of the more complex features of nouns, adjectives–which function as noun modifiers, and some of the other grammatical elements that relate closely to nouns.

One way of identifying a noun, as you’ve seen, is that it can serve the subject (casually, the topic) function of a sentence. One trick for this is to use the frame “________ is/are good.” (You could substitute another adjective for good.)

Dogs are good.

Rainbows are great.

Columbus is good.

Water is great.

However, this frame doesn’t exactly work in every case, because some nouns—alone, by themselves—don’t make grammatical subjects.

*Dog is good.

*Rainbow is good.

*Child is good.

*Noun is good.

What do you notice about all three of these examples? These are all singular nouns. What would make each of these sentences grammatical? Let’s try:

That dog is good.

Any rainbow is good.

My child is good.

The noun is good.

Adding a determiner to the noun “fixes” the subjects. But what about the previous examples, where Columbus and water were fine subjects on their own? Consider also the following:

Jazz is good.

Tofu is good.

Music is good.

Food is good.

There is some grammatical difference between a singular noun like dog and a singular noun like jazz. Let’s turn to some visual aids to sort this out. How would you label these pictures?

I bet you labeled the first set DOGS and DOG. One shows multiple dogs and the other shows a single dog, right?

But what about the second set? I bet you labeled the two pictures the same: TOFU. You may have put a phrase in each case: something like, BLOCK OF TOFU and PIECES OF TOFU, or maybe TOFU and TOFU SLICES. But I bet that you did NOT write TOFUS, with a plural {-s} morpheme. Why does dog get the {-s} morpheme but tofu doesn’t?

It’s because tofu is not a noun that typically has a plural usage; rather, the singular form is used in all cases. Similarly, we don’t say jazzes to refer to multiple jazz songs or styles; and we don’t say beefs to refer to multiple pieces of beef.

The words tofu, jazz, and beef are all mass nouns, a type of noncount noun: nouns that do not represent countable items. Often these are nouns that refer to a super-set of a smaller set, i.e. a more general concept. For instance, beef encompasses all meat that comes from cows, whether it’s in the form of a burger/burgers, hot dog/hot dogs, or steak/steaks. Likewise, jazz encompasses all instances of music (or dance) that has the quality of being jazzy.

Keywords

- mass nouns / noncount nouns: nouns that generally do not have plural forms because their reference cannot be divided into individual units

Many nouns have both count and noncount senses. You will notice that in the count sense, they are ungrammatical without a determiner. In the noncount sense, they are grammatical without a determiner.

noncount: Coffee is necessary.

count: *Coffee is the one I wanted.

noncount: Business is booming.

count: *Business is the best one in the neighborhood.

noncount: War is evil.

count: *War was the deadliest.

Each starred sentence requires us to interpret the subject as something specific, not general—as an instance of a concept, not the category of the concept. If we stick in a determiner in each case, we get something grammatical:

That coffee is the one I wanted.

That business is the best one in the neighborhood.

That war was the deadliest.

Note that we can typically come up with occasions to use the plural forms of these nouns too, though:

I drank five coffees.

The neighborhood has many new businesses.

Wars are bad.

So we’ve just discovered one of the rules of English noun phrases: a singular count noun requires a determiner.

Note that it isn’t the inverse: it isn’t that noncount nouns can’t have determiners. They often do! However, some determiners (specifically quantifiers) that are grammatical with noncount nouns are ungrammatical with count nouns, and vice versa. Check it:

Some coffee was brewing.

Some coffees were brewing.

BUT

Little coffee was brewing.

*Little coffees were brewing. (means something different)

I’ve prepared a little experiment to elicit your intuitions about some of this. Take the experiment before moving ahead in the reading!

DID YOU TAKE THE EXPERIMENT YET?!?!?!

There is one type of noncount noun that typically cannot take a determiner at all, however: proper nouns. Any of these would probably seem weird:

*The Columbus is a nice city.

*That Miles Davis was an incredible musician.

*A Michelle Obama is a good dancer.

*The The Ohio State University is the best damn school in the land.

Proper nouns inherently represent concepts of which there is one and only one instance. Even this rule is not 100% followed, however: we can think of rhetorical circumstances where using a determiner with a proper noun does make sense…

My Columbus is better than your Columbus.

This Thanksgiving was better than last Thanksgiving.

Everyone should have a Justin Timberlake in their life.

We’ve just discovered some rules related to the internal structure of noun phrases. Now try to build some noun phrases for yourself, before we move on.

2. Determiners

We just discussed a lot about determiners as they are relevant to different noun sub-categories. But back up: What is the function of determiners, actually? They restrict or specify the reference of the noun. Let’s look a little more closely at what this means.

Go back to 2017, when Beyoncé gave birth to her twins. Now, imagine a person who does not know that Beyoncé had been pregnant at all, let alone with twins. Let’s call this person Becky. Consider the following (hypothetical) exchanges between me and Becky:

Lauren: Beyoncé had twins.

Becky: Good for her.

Lauren: Beyoncé had the twins.

Becky: Oh? I didn’t realize she was pregnant.

Why does the simple presence of a determiner the in the second version of my statement change Becky’s response?

Beyoncé had twins.

Beyoncé had the twins.

The addition of the causes you to interpret the twins in question as being a specific set—a set that Becky is assumed to already know about. But Beyoncé’s pregnancy is not already known by Becky, so Becky seems somewhat surprised: “the twins” presumes that Becky knows already which twins, when in fact she did not previously know there were any twins at all.

This difference between new and old information is part of what drives the use of different determiners.

The definite determiner the introduces old—already known—information, whereas the indefinite determiner a/an can introduce new information:

OLD INFORMATION – DEFINITE DETERMINER

Becky: Beyoncé just released the new album.

Lauren: YES! I’ve been waiting!

NEW INFORMATION – INDEFINITE DETERMINER

Becky: Beyoncé has a new album out.

Lauren: Cool, I didn’t know she was working in the studio again.

Another referential difference signaled by determiners is proximity: whether the item in question is closer to or further away from the speaker. Consider:

I love this song by 21 Pilots.

I love that song by 21 Pilots.

In both cases, it is assumed that the speaker and listener are both already familiar with the song–it’s old information. What is the difference between this song and that song?

This song means the song playing right now, whereas that song probably means a song not currently playing. Metaphorically, this song is closer to the speaker, whereas that song is farther away (here, in time, not physical distance). This (!) class of pronouns is called demonstratives: this/these are the proximal demonstratives; that/those are the distal demonstratives.

You might have noticed that these (darnit, I can’t stop!) determiners are also sometimes used without a noun at all:

I love these.

That is mine.

THIS.

Indeed, many of the words that function as determiners (with a noun, as part of a noun phrase) can also function as pronouns (occurring independently). In these cases, the pronoun is the head of the noun phrase–and is the complete noun phrase, as we’ve already seen. Identify which pronouns are pronouns versus determiners in the following examples:

3. Adjectives

We know that a noun phrase must have a head. We know that it could also have a determiner (and there are lots of different kinds of those). Another major lexical category that relates to nouns is adjectives. An adjective modifies a noun by attributing some property or quality to it. Consider the following:

the good hair

my best friend

his favorite animal

some delicious pizza

Can you identify a pattern for the order of determiners, adjectives, and nouns when they all occur together in a noun phrase? Why are the following ungrammatical?

*good the hair

*friend best my

*favorite animal his

*some pizza delicious

Adjectives occasionally come after a noun instead of before; these can sound poetic in Modern English:

a story long-forgotten

a smell so sweet

with hair brown and eyes blue

melodies pure and true

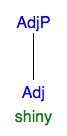

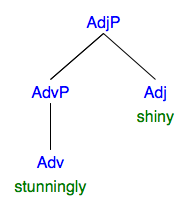

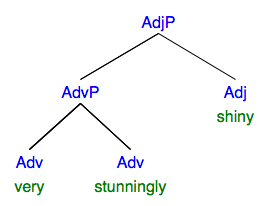

Remember too, that adjectives themselves head adjective phrases (AdjPs). So within an NP, when there is an adjective, there is actually an AdjP, which functions to modify the noun. What is the internal structure of an AdjP? It could be just an adjective, or it could be an adjective modified by something else, like an AdvP (an adverb plus…). Here are some examples of AdjPs, with growing complexity:

Label the following tree! (And bring any questions you have about it to class with you.)

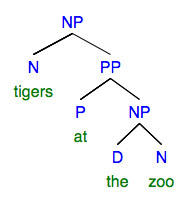

4. Prepositional Phrases

A final element (in addition to determiners and adjective phrases) that often modifies nouns is a prepositional phrase. Because it has many different functions, we will discuss it in several of our modules. Prepositional phrases relate to nouns in two ways: internally and externally.

Internally, the composition of a prepositional phrase is always a preposition plus a noun phrase (which is called the object of the preposition, as you already know). Here is the “Schoolhouse Rocks!” description of “prepositions”:

Do most all of the work

Of, on, to, with, in, from

By, for, at, over, across

And many others do their jobs,

Which is simply to connect

Their noun or pronoun object

To some other word in the sentence.

Can you spot the mistake in this video?!

I want to rephrase this a bit for more accuracy: prepositions “express a relationship between their noun phrase object and another word or phrase.” Consider the following, from Module 3:

ducklings in the pond

ballerinas from the company

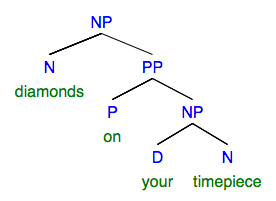

diamonds on your timepiece

tigers at the zoo

In (a), in connects the pond to ducklings, specifying a relationship between them. In (b), from connects the company to ballerinas, specifying a relationship between them. And so on.

Externally, as the above examples show, one of the functions of a PP is to modify a noun, forming a larger noun phrase—just like adjectives do. So in the pond attributes a property or state to ducklings; on your timepiece attributes a property or state to diamonds, and so on.

A PP modifying a noun will almost always come after the noun, as in the above cases. Here are two of the above phrase structure trees:

Can you draw trees for the remaining two NPs from above the above list? From the company and in the pond. Try it!

5. Conjunctions

The final element whose relation to nouns I want to discuss is (coordinating) conjunctions. They can join two nouns or two noun phrases together, just as they can do with every other kind of word and phrase.

I need sugar and flour.

I need some sugar and some flour.

I need sugar from the top shelf and flour from the bottom shelf.

We won’t worry too much about drawing trees when it comes to coordinating conjunctions. Phew, right?!

To conclude…put these pieces together and we have most of the components of NPs. Can you identify each element of each NP below? First, label each word. Then, draw the tree for each full NP. Bring your responses to class!

computer

a computer

my old computer

my new computer from Apple

6. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 5, Basic Unit

Complete before moving on to the next unit!