Module 6: Verbs and Related Stuff

Module 6: Basic Unit

Contents of Basic Unit:

Nouns are one primary category of content words, to which adjectives (and adjectivals) relate functionally. The other primary category is verbs. In this short unit we’ll explore a little more about verbs and related things.

As you know by now, verb phrases are required in a sentence (clause), and a verb phrase always has a verb as its head. We often casually refer to verbs as “action words” or “words describing an activity,” but this isn’t really accurate. What is the “action” described by the following verbs?

Martin is great.

The movie seems interesting.

I believe you.

This tastes delicious.

She persists.

Here are a few alternative definitions of a verb, rooted in its function rather than its reference:

a) a word that takes the {-s}, {-ed}, {-ing}, and {-en} inflection

b) the head of a verb phrase

c) the core of a sentence (clause)

d) something that needs a subject and predicates something of that subject

We discussed (a) all the way back in our unit on morphology, but it’s worth recalling the difference here between the verb inflections. But here’s a handy trick to simplify all this: if there is an {-ing} form of a word, it is a verb! English shows variation in its other inflections, but not this one. So every verb has a present participle {-ing} form which is expressed as –ing.

Some examples of verbs and their inflections are given below. Remember, regular verbs have {-ed} ending for both their past tense and past participle forms, but irregular verbs use different morphological forms. Which of the verbs below are regular and which are irregular?

| Bare (present tense, non-third person singular; present tense plural; infinitive) | Present tense, third-person singular | Past tense | Present participle | Past participle |

| type | types | typed | typing | typed |

| listen | listens | listened | listening | listened |

| fall | falls | fell | falling | fallen |

| behave | behaves | behaved | behaving | behaved |

| know | knows | knew | knowing | known |

| catch | catches | caught | catching | caught |

Here are some examples of these verbs in context. For practice, name the verb inflection in each one.

I typed the paper last night.

I have typed five papers this year.

The senator listens to her constituents.

The senator is listening to their concerns right now.

I falled! (just kidding; this is what my toddler says)

I fell off the seat.

Help, I’m falling!

The children behave like children.

They had behaved like babies when they were smaller.

I knew it all along.

I have always known it.

He caught the ball.

He is catching the ball!

He has caught the ball.

We will talk more about the differences in grammatical meaning when these different verb inflections are used, in Module 8.

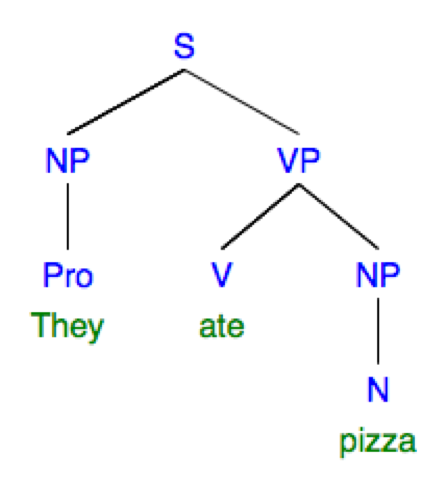

The next two definitions, (b) and (c), are related: verbs are the head of a verb phrase, and the core of a sentence. In our example below from a previous module, ate is the head of the verb phrase ate pizza:

What do I mean by the “core of a sentence (clause)?” Well, without the verb ate, there would be no sentence at all. We would have they and pizza, but no way to understand the relationship between these two nouns. (It is possible that you could interpret “They pizza” as meaning “They ARE pizza”—maybe it’s Halloween!—that sentence is grammatical in African American English, for instance. But, if what I mean is “they ATE pizza,” the only way to understand that is by the presence of the verb EAT.)

Consider other examples: what happens if you remove the verb?

She left.

I want more coffee.

He gave me the pastry.

The following are not sentences:

She.

I more coffee.

He me the pastry.

Without the verbs, there is no syntactic reason for the nouns. So you can think of the verb as providing the reason for the nouns to be there in the first place.

left

want

gave

From these “kernels” of meaning more syntactic requirements arise: somebody left; somebody wants something; somebody gave something to someone. In a sense, the presence of a verb creates a template to be filled in to create the rest of a sentence/clause. We will go way more in depth with this in the next module! But here consider the difference between having just a noun and just a verb.

Just a noun:

- Sharon

- President

- streams

Just a verb:

- walk

- voted

- swims

Sharon could be playing lots of different roles in a clause: it could be the subject, but it could also be part of the verb phrase, or the object of a preposition:

Sharon dances.

I like Sharon.

I talked to Sharon.

Likewise with president and streams:

President seems like a hard job.

I want to be President!

I can’t wait to vote for President.

Streams are beautiful.

I like running through streams.

I love streams.

Now consider just the verbs. If we have walk, there must be someone/something to do the walking:

Lions walk.

I walk to school.

If we have voted, there must be someone who did the voting; there might also be someone they voted FOR:

I voted.

She voted for me.

And if we have only swims, there will at least be someone/something doing the swimming, and possibly something being swum:

My neighbor swims.

My dad swims a mile every morning.

These examples all show one thing: syntactically, verbs create the requirement for a subject. And some verbs create the requirement or expectation for other units of meaning to be present as well. This what I mean by verbs being the “core” of a sentence.

This brings us to our last definition of verb:

d) something that predicates something of the subject

We have already seen (d) in action: verbs create the requirement for a subject; and, the verb says something about—in fancier terms, predicates something of—the subject. This could be ascribing the subject a property, declaring a state of being of the subject, or—as we commonly think of it—naming “an action” being done by the subject.

I want to be really clear about what I mean in using the term “predicate” this way. Here is the Merriam-Webster definition of “predicate”–make sure to look at the noun AND verb definitions:

Merriam-Webster definition of “predicate”

[When we are using the verb form, we pronounce the final syllable with a “long A” sound: “a verb pred-uh-KATES something of a subject.” When we are using the noun form, we pronounce it with a “schwa” or “short I” sound: “that’s the pred-uh-KIT.”]

A verb predicates something of a subject. For instance:

(a) Lions walk.

(b) Sharon voted for Trump.

(c) Steve campaigned for Clinton.

(a) walk predicates walking of lions.

(b) voted predicates voting of Sharon.

(c) campaigned predicates campaigning of Steve.

And so on. You have to think a little abstractly to get to this way of understanding a sentence, I think, but it is crucial!

2. More on adverbs

The remaining content word category, adverbs, has the primary function of modifying a verb, to change something about how we understand whatever is predicated by the verb.

Examples:

Lions walk slowly.

Sharon voted enthusiastically.

Steve campaigned tirelessly.

In what sense do these adverbs modify the verbs before them? Slowly describes HOW the walking occurs. Enthusiastically describes HOW the voting occurred. And tirelessly describes HOW Steve campaigned. Adverbs’ most common function is to modify verbs. But wait—they might modify a whole verb phrase instead!

Lions walk five miles slowly.

Sharon voted for Trump enthusiastically.

Steve campaigned for Clinton tirelessly.

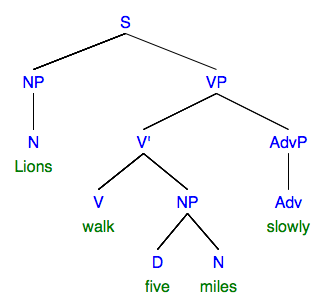

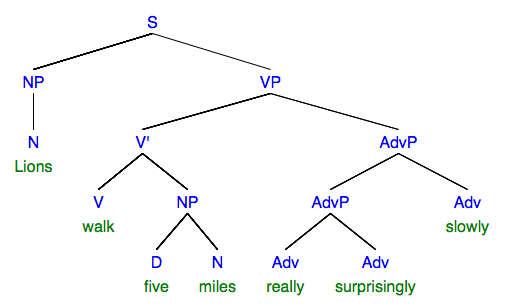

Now, slowly tells us not only how lions walk, but specifically how they walk five miles. Enthusiastically is not just how Sharon voted, but how she voted for Trump. And tirelessly is not just how Steve campaigned, but specifically how he campaigned for Clinton. Here, we say that the adverb modifies the verb phrase—yet it is also part of the verb phrase! In our phrase structure trees, we can use our intermediate “bar” level of V’ to note this relationship:

This means:

- walking is being predicated of lions

- five miles is what is being walked

- slowly is how walk five miles happens

Again, the V’ (“V-bar”) just says: walk five miles could be a complete verb phrase, but it is not yet, since there is an adverb phrase.

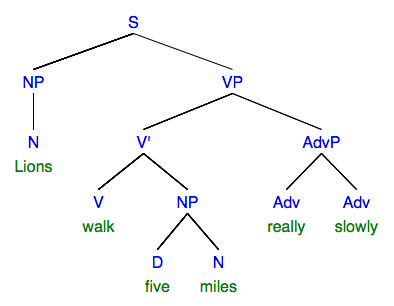

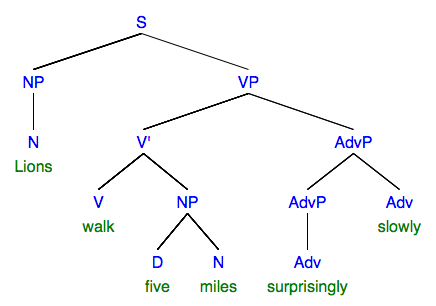

Now, why did I create an AdvP instead of just an Adv? Because adverbs are heads of adverb phrases, just like nouns are heads of noun phrases and adjectives are heads of adjective phrases. This adverb COULD be additionally modified by another adverb—either a content-ful adverb or a degree adverb. See if you can determine the reasoning behind the three trees below:

Before class, use the Google form to enter three examples of Adverb Phrases you find “in the wild”: an adverb modified by another adverb. (If I’ve returned HW2 to you by now, feel free to enter examples from your corpus searches.)

3. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 6, Basic Unit

Complete this before moving on to the next unit!