Module 8: Grammatical Meanings and their Expression

Module 8: Advanced Unit

GRAMMATICAL MEANINGS AND THEIR EXPRESSION

Contents of Advanced Unit:

- Tense

- Introducing the verb group

- Aspect

- Modality

- Voice

- Mood

- Polarity

- Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 8, Advanced Unit

1. Tense

Tense is the first in a packaged set of grammatical meanings often referred to as the “Tense-Aspect-Mood” system of a language (i.e. “TAM”; also called “Tense-Mood-Aspect” or TMA). Together, these three categories of grammatical meaning cover the expression of concepts related to time (tense), the flow of time (aspect), and truth/veracity (mood). Definitions of these categories are not exactly unified across linguistics, so once again, I’ll be using definitions that make sense to me.

Why are these three categories lumped together? Across languages they tend to all be expressed within the verb phrase. Thus, in most of this module, we’ll be focusing on verbs more. I know you’re glad to be thinking verbally again.

English has present tense and past tense. The morphemes third-person singular present-tense {-s} and past-tense {-ed} show that verbs inflect to display tense. But let’s get more formal about what’s going on with a present versus past tense expression. Consider the following pictured event, which comes from Reader’s Digest:

Let’s call this event abstractly, in logical form, LICK (CAT, CAT). How would you turn this into a concrete sentence/description? Tense is one of the things you have to “decide” about in order to make a sentence.

You could situate the event as happening at the same time as you are uttering the statement. That would be present tense:

The cat licks itself.

Or you could situate the event as having happened at a time prior to when you utter the statement. That would be past tense:

The cat licked itself.

And this is all that English tense, on its own, does: it situates the event under description in a temporal relationship either before (past tense) or simultaneous with (present tense) the utterance describing it. We can summarize those:

English Present v. Past Tense

present: E = U

past: E < U

E is Event; U is Utterance

Now, there’s something interesting about English present tense. Imagine that you are in the Union talking on the phone with a friend, and you see something extraordinary: a dancing flashmob!

Let’s say you want to tell the person on the phone what is going on. Would you describe the scene with the following?

I suspect you would not. But the event is happening presently, right now as you speak. It is simultaneous to the time of utterance. Why can’t you just use present tense?

You could say this instead:

Whoah! People are dancing!

We basically “fixed” this sentence by adding an auxiliary verb (are) but also changing the inflection on the main verb (dance > dancing). More on this in the next section, as it pertains to aspect! (Notice that *People are dance would be ungrammatical.)

The truth is, the simple English present tense is rarely used to describe events happening simultaneous with the moment of utterance (despite the implication and our basic definition of “present”), and its use is limited to certain kinds of events. Consider a context in which you might utter any of the following:

People dance

Misty Copeland dances ballet

I dance in my pajamas

The train leaves at 5 pm

The train arrives on time

The train runs smoothly

Babies drink milk

The baby eats solid food

The baby wakes up

To continue this little thought experiment: What kinds of adverbial phrases could you add or not add after each of these clauses? Can you add any of the following?

right now

at this moment

as I speak

These adverbial phrases indicate the simultaneity of an event with the time its description is uttered; in other words they emphasize the presentness. If you are using simple “present” tense, shouldn’t you be able to use these phrases? Rate the following sentences for grammaticality:

Of the sentences you just rated, a few don’t sound impossible, but compare them to the following:

People are dancing right now

Misty Copeland is dancing ballet at this moment

I am dancing in my pajamas as I speak

The train is leaving right now at 5 pm

The train is arriving on time at this moment

The train is running smoothly as I speak

Babies are drinking milk right now

The baby is eating solid food at this moment

The baby is waking up as I speak

I am willing to bet $10 that you prefer this second list to the list above with the “bare” present tense.

So, what’s the point? Rather than describing things that are actually happening right now at this moment as we speak, the simple English present tense instead is typically used to refer to habitual/repetitive actions or states of being; to future time; or to conditional statements. The following examples illustrate these contexts of use:

HABITUAL/REPETITIVE ACTIONS OR STATES OF BEING

Babies drink milk. (it’s just a fact about the world)

Misty Copeland dances ballet. (it’s her job)

The train arrives on time. (every day at 3 pm)

FUTURE TIME

The train leaves at 5 pm. (which is an hour from right now)

I dance in my pajamas in the show. (which is tonight, in five hours)

I teach at 9 am tomorrow.

CONDITIONAL STATEMENTS

The baby eats solid foods if she’s hungry.

The train runs smoothly when there is no precipitation.

People dance whenever they feel happy.

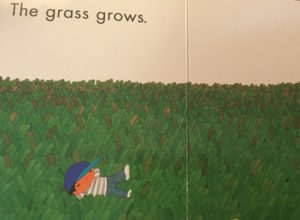

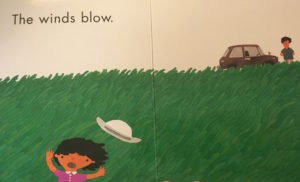

Simple present tense is also often used in narrative contexts, such as children’s books:

As you look through this list of uses of the simple present tense for things other than simple present time, you may be struck in particular by the use of present tense to reference future time. Isn’t this just “future tense,” you say? Wait a minute—why haven’t you talked about future tense at all?!

Tense is a category of grammatical meaning that is expressed through specific grammatical elements. We can clearly see a distinction between present and past tense, because our verb inflections change to encode them. In contrast, English does not have a grammatical future tense: there is no verb inflection (or lack of one) that encodes a temporal relationship of futurity between an event under description and the time of utterance. Rather, we have other means of indicating futureness—we saw one above, which is the use of present-tense verb forms, with futurity indicated by adverbial phrases or just being interpretable from context.

This points to an important general linguistic distinction between meanings languages can express and the grammatical elements used to express them. All languages can express senses of past time, present time, future time, and gradations within them—but languages do so differently. English happens to not use verb inflections to indicate futurity, but other languages do. Finnish (like English) has a past tense and no future tense. Hindi has a past tense and future tense. Yagaria has a future tense but no past tense. Cantonese and Chamorro have no past tense or future tense. (Check out WALS, the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures, to search for languages with different grammatical features!)

The upshot: different languages (and dialects) do things differently. English has a present and past tense. Future time is expressed in other ways.

2. Introducing the verb group

Let’s revisit the sentences with auxiliary verb BE from above:

People are dancing right now.

Misty Copeland is dancing ballet at this moment.

I am dancing in my pajamas as I speak.

The train is leaving right now at 5 pm.

The train is arriving on time at this moment.

The train is running smoothly as I speak.

Babies are drinking milk right now.

The baby is eating solid food at this moment.

The baby is waking up as I speak.

Each of these sentences contains an auxiliary verb in addition to the main verb (specifically a form of BE). And each sounds—generally—more grammatical as a description of something happening simultaneous with the utterance, compared to a sentence with just the simple present tense verb. But why?

We already knew, from our introduction of auxiliary verbs as a lexical category, that verb phrases can include more than one verb. Now, we will get specific about why sometimes there is more than one verb, and what grammatical categories of meaning are expressed by combinations of verbs. There’s a lot to do here. Let’s go!

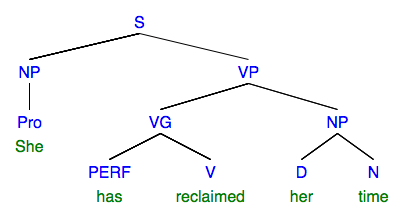

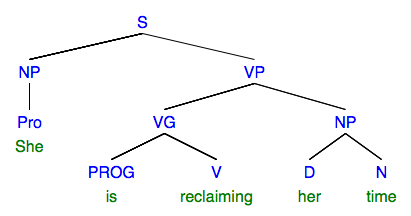

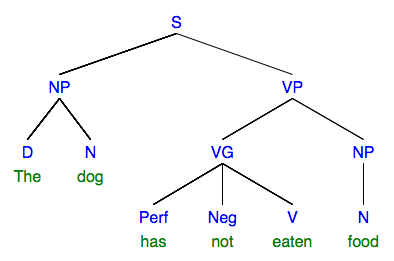

In our approach, we will follow Elly van Gelderen’s system of calling the entire combination of verbs the verb group, and we’ll abbreviate the verb group with “VG.” Observe the following verb groups:

is dancing

have danced

could have danced

has been danced

had been being danced

will have been being danced

In each, there is a main verb carrying lexical meaning: DANCE. In addition, each contains at least one auxiliary verb and in some cases more than one: BE, HAVE, COULD, WILL.

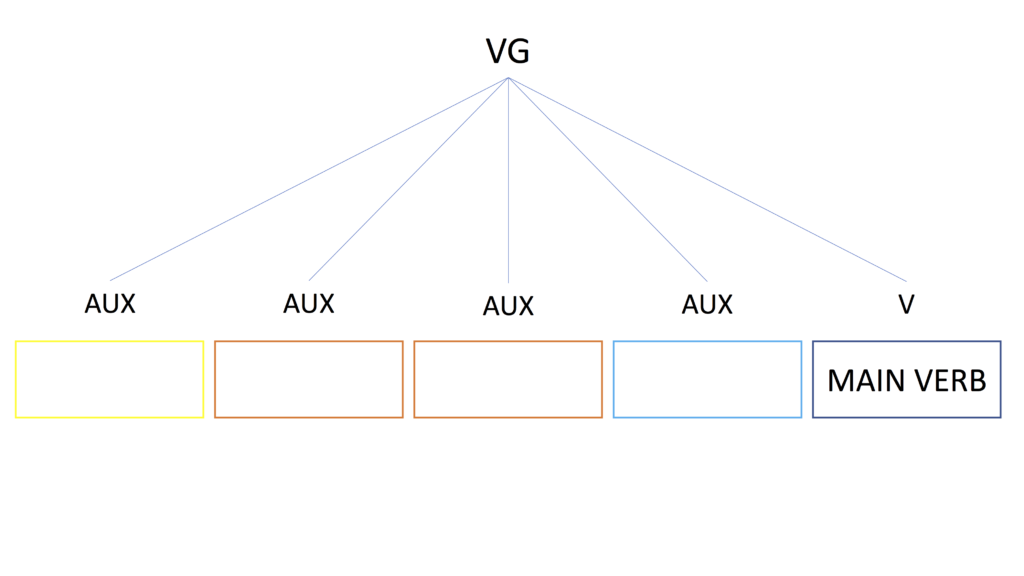

Every VG will contain at least a main verb, and optionally between one and four auxiliary verbs. That means a verb group can be as small as one verb, and as large as five!

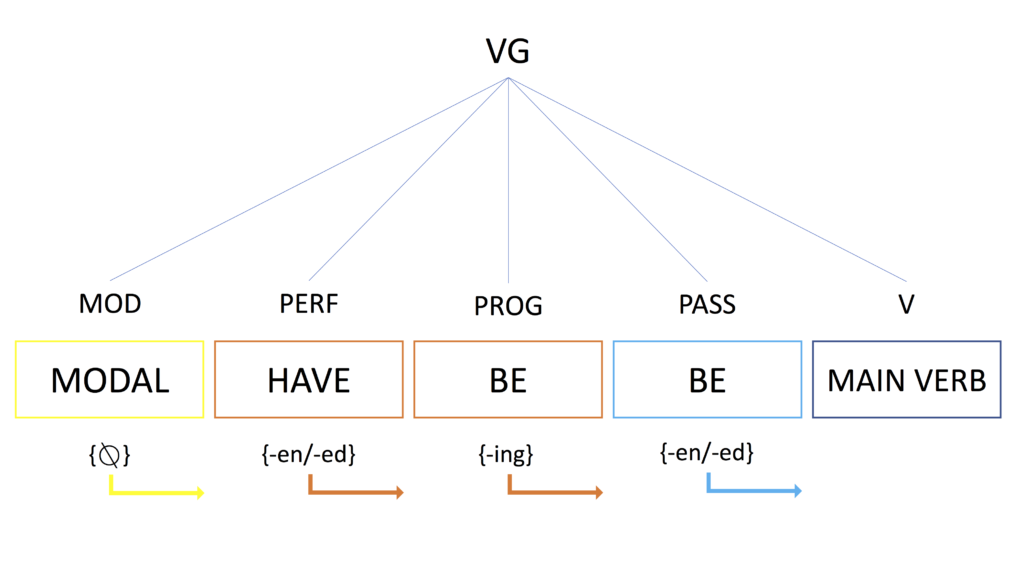

Here is a schematization of the VG:

The presence of every auxiliary verb in combination with the main verb expresses one or more of three grammatical categories of meaning: aspect, voice, and modality.

Note: Before we proceed, you may want to review the verb inflections again. Understanding the VG will be much more difficult if you do not recognize the inflections right away.

3. Aspect

We begin with aspect, because like tense, it relates to time. In the sentences above, we actually “fixed” our simple present tense sentences by adding aspectual meaning.

3a. Aspectual meaning categories

Whereas tense locates an event relative to the time its description is uttered, aspect expresses the division or flow of time within a past or present temporal location.

In English, we have two grammatically-marked aspectual categories: progressive and perfect. I’ll give definitions in a second, but their semantic meanings are really best grasped by considering how they are used in context. Consider the following:

People are dancing

People have danced

When would you say one versus the other? Can we do the “add an adverb phrase” trick to help us think about the contexts they could describe? These work for me:

People are dancing right now and they won’t stop.

People have danced since the beginning of humanity.

Now, if we try to swap the adverbials between the two clauses, we end up with odd-sounding sentences:

People are dancing since the beginning of humanity.

People have danced right now and they won’t stop.

Why do these sound odd? The first VG, are dancing, is progressive aspect. This signals a continuity to the event such that it’s viewed as something in-progress. Importantly, it could be in-progress in the present, or it could have been in-progress in the past:

present progressive: People are dancing at this moment and they won’t stop.

past progressive: People were dancing at that moment and they wouldn’t stop.

In the present progressive, the event occurs at the time of utterance and it will continue occurring after the utterance: it is ongoing. In the past progressive, the event occurred prior to the utterance, and at the time it occurred, it was a continuously-occurring action.

The second VG, have danced, is perfect aspect. This signals a completion or “closedness” of the event, while also signaling a closeness to either present or past time. As with the progressive, perfect aspect can occur in either present or past tense:

present perfect: People have danced since the beginning of humanity.

past perfect: People had danced long before the birth of Christ.

In present perfect, the event is possibly still happening at the time of utterance. In contrast, in past perfect, the event is not still happening at the time of utterance, and in fact was completed by some past time.

Perfect aspect locates the occurrence of an event either very close to the time of utterance (present tense), or very close to some time prior to the time of utterance (past tense).

Personally, I think perfect aspect is much more nuanced and harder to understand than progressive, so let’s look at some more examples of when you would/wouldn’t use perfect aspect.

Consider these present perfect examples, with potential sentence completions that are either good or bad (e.g., sensical or nonsensical).

| Sentence beginning | GOOD completion | BAD completion |

| We have eaten all the popcorn… | …and the movie is about to start | …by the time the movie started |

| They have danced all night… | …and they don’t show any signs of stopping | …and they stopped |

Perfect aspect describes something that occurred prior to the moment of utterance; the question is just how close to the moment of utterance. In the first example, if I say “we have eaten all the popcorn,” it’s true that the action of eating popcorn has already occurred and was completed prior to my utterance—but it has happened very close in time to my utterance, and it is relevant to the present time. So the past tense completion of “by the time the movie started” doesn’t work.

In the second example, if I say “they have danced all night,” it’s ambiguous as to whether they are still dancing or not at the time of utterance—that interpretation depends on what follows, or perhaps just knowing the context. But what must be the case is that dancing has already occurred before the time of utterance. Yet the dancing is relevant to the time of utterance, and if it is completed, it likely only completed shortly before the utterance. So again, a simple past tense completion clause “and they stopped” doesn’t work.

Now compare to statements in past perfect. I’ve swapped the same possible completions between GOOD and BAD:

| Sentence beginning | GOOD completion | BAD completion |

| We had eaten all the popcorn… | …by the time the movie started | …and the movie is about to start |

| They had danced all night… | …and they stopped | …and they don’t show any signs of stopping |

With past perfect, the event occurred and was completed in the past, prior to the time of utterance. Thus, it doesn’t make sense to tag on things that are about the same event in the present tense; hence the present tense completions now become bad.

Not only do we have present and past tense in combination with perfect and progressive aspect, but we also have both aspect markings possible in a single verb group—still with present or past tense! Check it out:

present perfect progressive: People have been dancing

past perfect progressive: People had been dancing

Can you articulate what the combined meanings of such VGs are?

Here’s an attempt to illustrate the relations between present/past tense and perfect/progressive aspect. This schematic is inspired by material in Elly van Gelderen’s textbook, An Introduction to the Grammar of English.

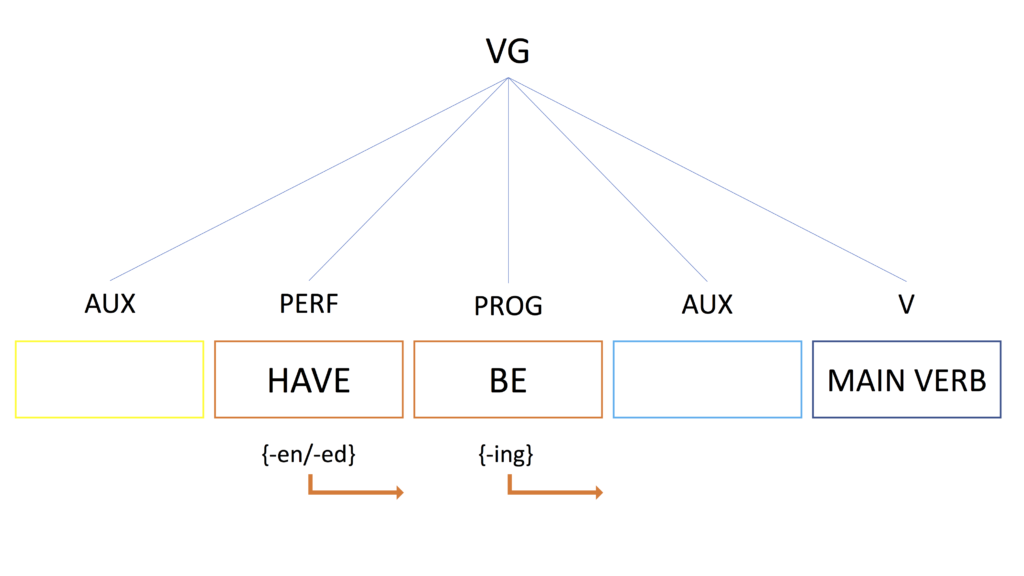

3b. Syntactic expression of aspect

Now that we have a little sense of what these combinations mean, let’s deal with how they’re structured in the VG.

The grammatical meanings of aspect, modality, and voice are each expressed in the VG involves a two-part combination: a specific auxiliary verb, plus a specific inflection on the next verb in the series. We call this phenomenon affix-hop. It is as if the inflection is “packaged” with the auxiliary verb, but then “hops” from the auxiliary verb over to the next verb in the sequence.

Affix-hop in the VG

- Grammatical meanings of aspect, modality, and voice are expressed in the Verb Group are encoded by:

- a specific auxiliary verb, plus

- a specific inflection on the next verb in the VG

To understand affix-hop, see that the following are ungrammatical:

*People have dance

*People are dance

What’s missing? In both cases, the verb after the auxiliary verb has the “wrong” inflection. We know this because to fix them, we only need to change the inflection on the main verb:

People have danced

People are dancing

Aspectual meaning is marked by a combination of a specific auxiliary verb and an inflection on the next verb. And it doesn’t matter how many verbs there are in a VG: the inflection goes to the next verb down the line. So that could be the main verb, as above, but it might be another auxiliary verb.

Perfect aspect is expressed by a combination of the auxiliary HAVE plus the past participle {-en/-ed} inflection on the next verb. Here are examples:

PERFECT ASPECT EXAMPLES

HAVE + {-en/-ed}

have eaten

had bought

has given

had ridden

have seen

has warned

had typed

Every verb after the auxiliary HAVE is in the past participle form. (In fact, this is the primary way we have of identifying that there are different past tense v. past participle forms in English: we say I gave but I have given, with gave in past tense but past participle given when auxiliary HAVE is there.)

What accounts for the differing forms of HAVE itself, though? Why sometimes have, had, or has?

First is tense: the auxiliary HAVE is carrying the tense inflection for present versus past perfect. Second is subject-verb agreement: have and has will be used with different subjects, though they are both present tense. In the cases above, HAVE is the finite verb: it inflects for tense and subject-verb agreement.

Progressive aspect is expressed by a combination of the BE verb plus a present participle {-ing} inflection on the next verb. Examples:

PROGRESSIVE ASPECT EXAMPLES

BE + {-ing}

are eating

was buying

is giving

were riding

am seeing

is warning

was typing

Again, the form of the auxiliary BE is determined by tense (present or past) and subject-verb agreement. Here, BE is the finite verb.

What if we have both perfect and progressive aspect? Then the auxiliary HAVE (perfect) comes first, and kicks its {-en/-ed} inflection over to the next verb—which is auxiliary BE (progressive). Auxiliary BE then kicks its {-ing} inflection over to the next verb. In the examples below, that’s the main verb:

PERFECT + PROGRESSIVE

HAVE {-en/-ed}

BE {-ing}

have been dancing

had been eating

has been watching

have been kicking

To summarize the syntactic expression of aspect:

auxiliary verb inflection on next verb

perfect HAVE {-en/-ed} (past participle)

progressive BE {-ing} (present participle)

Now let’s think about the whole VG. We said that a maximal VG includes four auxiliary verbs. Perfect and progressive aspect account for two of those slots. Let’s start to fill in our schema, and include the affix-hop:

Complete the following to check in on your understanding of tense and aspect:

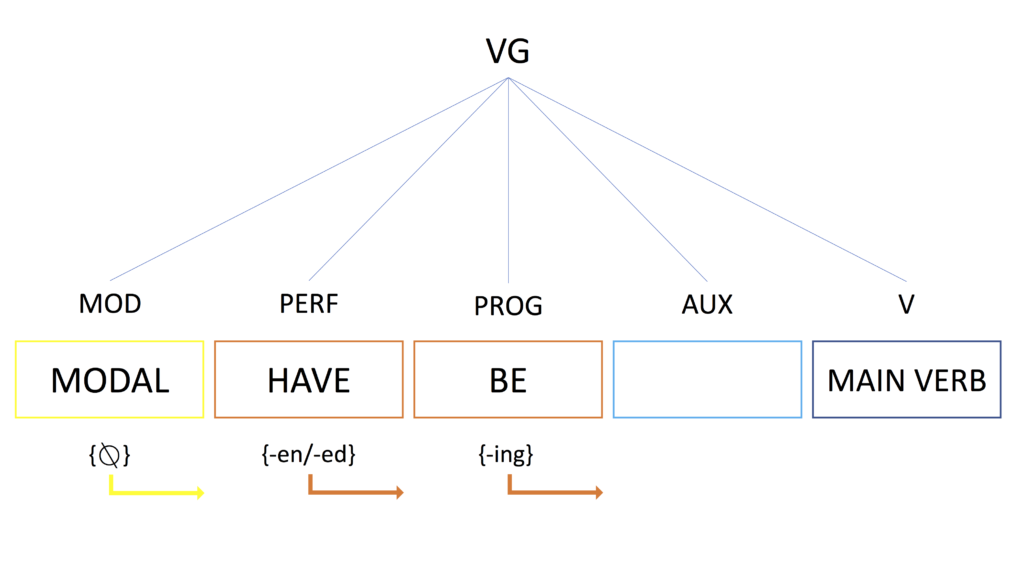

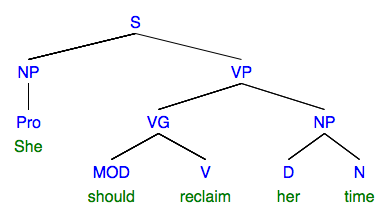

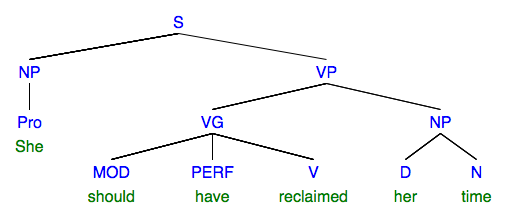

4. Modality

Our next category of grammatical meaning is modality. Modality expresses different stances or orientations of the speaker toward the utterance, pertaining to its truth-value, certainty, conditionality, likelihood, desirability, and so on.

Linguists describing English grammar use a diverse set of definitions and categorizations of modal meaning, which we won’t go too far into (take a semantics class if you want to learn more!). It will be enough for us to note that modality is expressed by the inclusion of modal auxiliary verbs, of which English has 9:

ENGLISH MODAL VERBS

can

could

will

would

may

might

must

shall

should

We can get into lots of fine-grained distinctions (and debates) about what each modal expresses and how it is used, but there are two uses that are unequivocally and clear-cut part of how English speakers use modals. First, we use modals to express future time. Primarily this is done through will which is a very straightforward future (along with the now-underused shall), but actually all of the modal verbs can have a future reading given the right context. Second—and relatedly—we use modals to express conditionality: things that are not certain to be the case, but are possible given some other factors.

Here are some examples of each of these meanings.

FUTURE TIME

We will eat at noon. (an hour from now)

The party tomorrow night should have dancing.

All tenants shall pay rent on time.

CONDITIONALITY

I might cut my hair, if it’s long enough to donate.

They would have liked the class if it had been more exciting.

If your old clunker doesn’t run anymore, you could donate it.

In the history of English, some of the modal verbs constituted more or less present+past tense verb pairs (e.g., can/could, will/would) and they were used as main verbs. But now, these verbs do not carry grammatical tense, and they actually take the place of tense-marking when they are present. The inflection a modal verb sends to the “affix-hop” process is a zero inflection—the next verb after a modal verb occurs in its base, uninflected form:

We would go.

She will go.

They can dance.

They could eat.

You should give.

I may give.

So, modality is expressed in the VG by a combination of a modal verb plus a zero inflection on the next verb. If a modal verb is present, it will always be the first verb in the VG. We can add this to our VG structure slots:

Modal verbs are the only category of verbs that do not inflect at all based on subject-verb agreement or tense. But because modal verbs seem to “absorb” the need for a sentence to contain a tensed verb, we say that modal verbs are inherently finite.

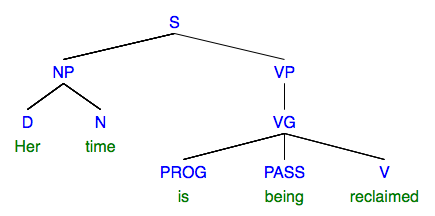

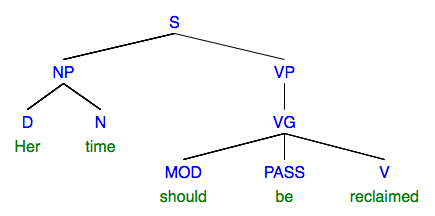

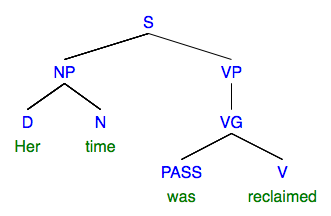

Let’s check out some examples of sentences with these meanings in the VG, so you can see how our trees will look from now on:

5. Voice

If there is one prescriptive grammar “rule” that most students seem to come to my class having heard a lot, it’s “Don’t use passive voice!” I disagree completely with this rule, but whether you follow it or not is ultimately up to you—what I care about is that you actually understand what passive voice is, in order to better assess when you might (or might not) want to use it.

Voice encodes the alignment between the thematic roles (semantic meanings) and syntactic functions (positions in the clause) of NPs. It is expressed by both the position(s) of the NP(s), and a combination of auxiliary verb and verb inflection in the Verb Group.

To understand voice, we need to remember our thematic roles, and the way that different thematic roles can be mapped on to different syntactic functions. We also need to remember our different sentence types: Voice distinctions are only relevant to transitive, ditransitive, and complex transitive sentences. You should understand why by the end of this section.

Here is a simple transitive sentence:

What are the thematic roles of SON and DONUT? I would consider SON to be AGENT, and DONUT to be PATIENT.

What are the syntactic functions of SON and DONUT? SON is the subject, and DONUT is the object.

That means that in this sentence, the AGENT is the SUBJECT, and the PATIENT is the OBJECT.

We can come up with lots of other simple sentences with this same alignment between thematic roles and syntactic functions:

Rapinoe kicked the ball beautifully.

Steffan stopped the ball.

Barrett saved the game at the last minute.

These sentences are all in active voice: the agent—the one acting—is the subject.

Consider, though, that you wanted to express the exact same content as each of these sentences, but you wanted to highlight the patient by putting it first:

The sprinkle donut was eaten by my son.

The ball was kicked beautifully by Rapinoe.

The ball was stopped by Steffan.

The game was saved at the last minute by Barrett.

What has happened here? Now the subject is the patient—the one being acted upon. The agent is not the subject. These sentences are in passive voice. Notice that in these passive sentences the agent is not syntactically required:

The sprinkle donut was eaten.

The goal was made beautifully.

The ball was stopped.

The game was saved at the last minute.

Sometimes people will say that passive voice is “bad” because “it removes the subject,” or “passive sentences don’t have subjects.” This couldn’t be more false! These sentences all have subjects—remember, subject is a syntactic position/function. That function is fulfilled in all of these sentences: the sprinkle donut; the goal; the ball; the game.

These people are probably confusing subject and agent: it is true that passive sentences often don’t have agents. And this allows for people to obfuscate, or avoid taking or attributing responsibility:

Mistakes were made.

The papers were lost.

The bills were not paid.

But there are times when we simply don’t know the agent, or when we’d rather not say, or when the agent simply isn’t relevant. In these cases, passive voice can sound much better than active. Consider the following sentences:

Our house was robbed!

Trump was elected.

The senator is accused of fraud.

What do you think about these active voice alternatives?

Someone robbed our house!

Voters elected Trump.

Banks accuse the senator of fraud.

Passive voice provides a way of omitting unknown or unimportant information—and that can come in handy.

Let’s look at how the active/passive alternation plays out over different types of verbs/clauses.

5a. Transitives

With transitive verbs, the direct object in an active clause becomes the subject in the passive clause. Whatever was the subject in the active clause typically becomes optional, and can be expressed in a by-headed prepositional phrase.

In an active transitive clause the AGENT is the subject, whereas in a passive clause the PATIENT is the subject.

Active Passive

Students protested the tax bill. The tax bill was protested by students.

Apple funded new iPads. New iPads were funded by Apple.

The weary professor taught the lesson. The lesson was taught by the weary professor.

5b. Ditransitives

Active ditransitive clauses have both a direct and indirect object, and either of these may become the subject in a passive clause. That means that either the THEME/PATIENT or RECIPIENT may become the subject in the passive clause. Check it out:

Active Passive

Apple gave the students new iPads. The students were given new iPads. (RECIPIENT as subject)

Apple gave the students new iPads. New iPads were given to the students. (THEME as subject)

The senator’s office emailed me a reply. I was emailed a reply. (RECIPIENT as subject)

The senator’s office emailed me a reply. A reply was emailed to me. (THEME as subject)

The chef baked cookies for the table. The table was baked cookies by the chef. (BENEFICIARY as subject)

The chef baked cookies for the table. Cookies were baked for the table. (PATIENT as subject)

5c. Complex transitives

Complex transitive clauses have both a direct object and a predicative NP/AdjP/PP. In the passive version of a complex transitive clause, the direct object from the active clause (typically THEME) again becomes the subject of the passive clause:

Active Passive

The agent made the actor a star. The actor was made a star.

They called her Mickey. She was called Mickey.

The students accorded the professor respect. The professor was accorded respect.

What grammatical expression does voice take in the verb group? What do you notice about all of the following passive clauses?

The actor was made a star.

The students were given new iPads.

The lesson was taught by the weary professor.

If you said, “They all include the BE verb,” YOU ARE RIGHT!!! Bingo. Just as aspect and modality are expressed by a combination of auxiliary verb and inflection on the following verb (affix-hop), so is voice.

Passive voice is expressed by the combination of the BE auxiliary verb plus a past participle {-en/-ed} inflection on the following verb. Examples:

PASSIVE VOICE EXAMPLES

BE + {-en/-ed}

is called

was believed

were elected

are alleged

am obliged

were judged

In the series of auxiliary verbs, the passive “slot” is the final one, filling out our verb group:

IMPORTANT NOTE: Any auxiliary that comes after another auxiliary will be inflected to reflect affix-hop. Thus, if the passive auxiliary comes after perfect HAVE, it will be in the past participle form been. If the passive auxiliary comes after progressive BE, it will be in the present participle form being. And if it’s after a modal verb, it will be in the uninflected form be. The same applies to the other auxiliaries. Here are some example series of verbs:

| MOD | PERF | PROG | PASS | V | |

| should | have | been | taken | ||

| may | be | taken | |||

| has | been | taking | |||

| were | being | taken | |||

| can | be | taking | |||

| shall | have | been | being | taken |

Here are some trees incorporating passive voice into the VG:

Common misconceptions about passive voice

- Any sentence with the BE verb is passive

- Any sentence with any auxiliary verb is passive

- Any sentence with a past participle is passive

- Any sentence without an AGENT is passive

- Any sentence without a direct object is passive

- Passive sentences don’t have subjects

- Passive sentences are “weak”

- Passive sentences are longer than active sentences

- Passive sentences obscure the meaning of a sentence

*You should be able to explain why each of these is a myth!

6. Mood

Grammatical mood overlaps a bit with modality, in that it involves something about the speaker’s stance or orientation to the utterance. But mood is really about what kind of utterance one is making, and what its purpose is: a statement? a command? a wish? etc.

(Take a minute to look up “grammatical mood” in google and notice how widely different uses of this term are. Some people use it to refer to exactly what I am calling modality; some people use five categories of mood, some use three—it’s all over the place!)

In Modern English we can talk about three distinct mood categories that correspond to different finite verb forms: declarative, imperative, and subjunctive. (Some people consider interrogative a mood, but it is distinguished grammatically by elements of structure different from the main verb itself, so we won’t consider that here.)

Declarative mood corresponds roughly to statements (assertions; propositions). Nearly all of the sentence examples we’ve seen so far in class have been declaratives. In declarative mood, the verb inflects in the “normal” ways we’ve investigated—for subject-verb agreement, tense, and to combine with auxiliaries of various kinds:

The cat eats its food.

The cats eat their food.

The cat ate its food.

The cats are eating their food.

Imperative mood corresponds to command forms. We’ve seen a few examples of these. Grammatically, imperatives are distinguished by a) always using the base form of the verb, and b) carrying an implicit, non-overt second-person subject. Note that any inflection on the verb makes a command form ungrammatical.

Eat your food.

*Eats your food.

*Ate your food.

*Eating your food.

You cannot put any auxiliary verbs in an imperative:

*Could eat your food!

*Be eat your food!

Subjunctive mood corresponds to non-factual statements; subjunctive clauses often express wishes, desires, or hypotheticals. Subjunctives are also distinguished by specific verb inflections, ones that do not vary by subject properties. For non-BE verbs, subjunctive is expressed with the uninflected verb form:

I recommend that the cat eat its food.

I insist that the cat eat its food indoors.

It is essential that the cat eat all its food, or else it will starve.

Note that the subjunctive here occurs in an embedded clause, and if we extract the clause from the sentence, it’s not grammatical—because the verb is not inflected to agree with the subject; in other words, there is no finite verb.

It doesn’t matter whether the main clause is in present or past tense—the subjunctive will still be the uninflected verb form. Here are the past tense versions of the clauses above:

I recommended that the cat eat its food.

I insisted that the cat eat its food indoors.

It was essential that the cat eat all its food, or else it would starve.

For BE verbs, “uninflected” be is used regardless of subject. Hence we have:

I insist that the cat be still for the shot.

I demand that my pets be adorable!

It is imperative that my cat be fluffy.

Again, the subjunctive occurs in each case in an embedded clause, which on its own would be ungrammatical because the verb is not inflected for the subject (is not finite):

*the cat be still for the show

*my pets be adorable

*my cat be fluffy

An important note! The subjunctive inflection appears on the finite verb. This means that, if the finite verb is auxiliary BE, it will follow the rule of being in the uninflected be form, regardless of subject in the clause. If the finite verb is auxiliary HAVE, it will occur as uninflected have:

I insisted that the cat be given a shot.

I demand that my pets be eating by 3 pm.

It is imperative that my cat have eaten by 3 pm.

A final word on subjunctives… some people say English doesn’t have a subjunctive anymore, but I think the above examples alone suffice to show that it does. I think what many people are referring to when they say this are examples like the following:

(a) If I were a rich woman, I’d give it all away.

(b) If I was a rich woman, I’d give it all away.

Many people consider (a) to be a subjunctive verb form—and because these days most people would produce (b) rather than (a), these folks argue that the subjunctive-declarative distinction is collapsed. But my go-to grammar experts, Pullum & Huddleston, hold that these special were forms are in fact not subjunctive at all, but a different category called irrealis. Food for thought.

Here’s a subjunctive sentence you probably hear a lot:

7. Polarity

Here are two English sentences, which mean the opposite of each other:

I love pizza.

I do not love pizza.

The difference between the two sentences is one of polarity, with the second sentence including the particle NOT as a form of negation. The first sentence is affirmative, and has what is called positive polarity. The second has what is called negative polarity. Polarity expresses the difference between affirmative and non-affirmative propositions.

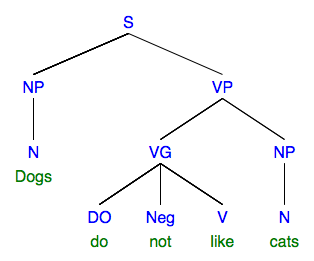

The primary thing to know about the expression of polarity in English is how negation works. And here we have to go back to the VG, which is where negation happens. The negative particle NOT is inserted after the first verb: either BE or the first auxiliary verb, if there is one:

It is not pizza.

I would not eat pizza

I have not eaten pizza

I am not eating pizza

The pizza has not been eaten

I have not been eating pizza

I could not have been eating pizza

You can’t put the negative particle anywhere else:

*It not is pizza.

*I would eat not pizza

*I not would eat pizza

*The pizza has been not eaten

*I have been not eating pizza

*I could have not been eating pizza

*I could have been not eating pizza

Well…the last three may be marginally grammatical for you…do they mean something different from the earlier versions, though?

if there is no auxiliary verb, we insert what’s called the “dummy” auxiliary DO before the negator:

*I not want pizza.

I do not want pizza.

*You not dance.

You do not dance.

(This is one of those rules that English learners of all types have to either acquire, in the case of native learners, or learn explicitly, in the case of nonnative learners: my son still, at age 3, sometimes omits the “dummy” DO auxiliary and produces sentences like, “Why you not like it?”)

We can incorporate the negator into our VG, just give it its own slot as below.

There are a couple of other interesting things involving negation in English. First, there are certain words—typically with adverbial meaning—that can only be used in the context of a negator. These are called negative polarity items (NPI). See examples:

Negative Polarity Items

I don’t want to eat anything.

*I want to eat anything.

She doesn’t eat gluten anymore.

*She eats gluten anymore.

The test shouldn’t take long.

*The test should take long.

But there is dialect variation! For many speakers in Midland dialects, She eats gluten anymore is fine…you might well be one of these speakers, as this is common in Ohio.

Second, there is dialect/register variation regarding negation: double negatives, anyone?

It don’t mean nothing (Richard Marx)

I never said nothing (Liz Phair)

You don’t know nothing. (Brooklyn Funk Essentials)

8. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 8, Advanced Unit

Complete this before moving on to the next unit!