Module 1: Goals for Studying Grammar

Module 1: Basic Unit

GOALS FOR STUDYING GRAMMAR

Contents of Basic Unit:

1. What is a language?

A language is a system of symbols used by humans to communicate. The system of a language consists of interlocking sub-systems. Linguists often divide the task of understanding language structure into three basic sub-systems:

- phonetics/phonology: how the sounds used in a language are produced and perceived

- morphology: how meaningful symbols, i.e. words, are created from sounds

- syntax: how meaningful combinations of symbols, i.e. phrases and sentences, are created from words

KEYWORDS

- phonetics/phonology: study of sound structures

- morphology: study of word structures

- syntax: study of sentence structures

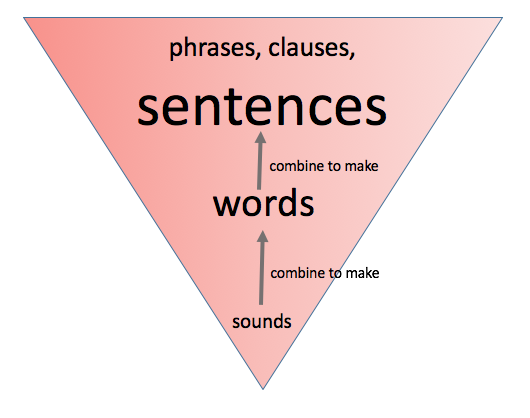

We can think of these sub-systems as progressing in size from smaller units (sounds) up to larger units (sentences), as in the triangle figure below. One fundamental structural property of language is that it is hierarchical: larger units are formed from the combination of smaller units. Our task, in trying to analyze a language, is to understand the patterns that determine how those smaller units fit together.

What does it mean to be concerned about any of these three primary levels of language structure, from a hierarchical perspective?

If we want to understand the structure of sounds (phonetics/phonology), we want to know a) how individual sounds are formed from combined movements by the tongue, lips, teeth, and other parts of the vocal tract; and b) which sounds and multi-sound combinations are present in English and which ones are not. English has some sounds that other languages do not have, and vice versa. English uses the sound represented by the letters “th” but German does not; Spanish uses a “trilled” or “rolled” “r” sound that English does not have. And, while flaks is an allowable sequence of sounds for an English word, the rearrangement of those sounds into the sequence ksafl is not. The sounds of English, and allowable sound combinations of English, are part of its phonological sub-system.

Moving up a level, if we want to understand the structure of words (morphology), we have to know which sounds can combine together to create words in English, so we cannot fully understand words without also understanding sounds. That’s the hierarchical structure! But we also need to understand the different ways in which sequences of sound can carry meaning (because a word means something, which makes it different from just a sound), and which units of meaning are able to combine with each other.

For example: the sequence of sounds “v-o” as in vo carries no meaning in English. By contrast, the sequence of sounds “d-e” as in de does carry a meaning. What is the meaning of de? Think about where de occurs at the beginnings of words like deactivate and debase).

Suppose I tell you right now, “To ‘vo’ a song is to turn it into a worse song than it already is.” You are now able to also understand a sentence containing the word devo as the combination of de- and vo. As in:

Limp Bizkit voed this George Michael song; I wish Devo would devo it.

Based on the meaning of vo and the meaning of de-, they can combine to create a word whose meaning you can understand as the sum of its parts. Limp Bizkit made a George Michael song worse than it already was; Devo can undo the damage. The new words vo and devo follow the patterns of English’s morphological sub-system.

Finally, consider for our purposes the “highest” level in the hierarchy, sentences (syntax). To understand English sentences, we need to understand the combinations of words that English speakers use to express meaning. Which combinations of words are allowable, and which are not?

We will talk more about this in class. I will be talking about an experiment I’ve conducted with students over the years. If you would like to take a few minutes to take the experiment before we address it in class, please click below to be taken to the experiment website! You might find it interesting.

In the experiment, participants read the following sentences (among others):

(1) Something fell on her head.

(2) Her started running circles in.

My prediction is that the first sentence (1) will sound much “better” to English speakers than the second sentence (2). How can you explain this? How would you “fix” sentence (2) so that it was “grammatical”? Your answers will reflect your knowledge of the rules of English and its sub-system of syntax.

2. Grammaticality

In this course, we will talk about grammaticality: whether a sentence (or phrase, or word) is well-formed according to the rules that make up the English language. What does this mean? If someone is a native speaker of English, they have internal, implicit knowledge of the rules of the English language. They follow the rules each time they generate a sentence, and they apply the rules in interpreting the sentences of other English speakers. But what kinds of rules are these?

KEYWORD

grammaticality: whether a sentence (or phrase, or word) is well-formed according to the rules that make up the language it comes from (in our case, English)

I said that native speakers have “internal, implicit knowledge” of the rules of English. This means that speakers do not need to be explicitly instructed in the rules. All typically developing humans acquire language naturally as children, as long as they interact with other humans speaking language. If someone grows up in a Japanese-speaking household and community, they will acquire Japanese; if they grow up in an English-speaking household and community, they will acquire English. And if they grow up in a bilingual English-Japanese household and community, they will likely acquire both languages.

Nobody has to sit children down and give them language lessons; at some point they just start producing single words (for my son, it was around 16 months), then two-word combinations (around 20 months for us), then three-word combinations (around 22 months), and so on. As they produce these words and eventually phrases, they are acquiring the rules that adult English speakers already know. Like that ksafl can’t be a word, and that “de-” can attach to the front of another word, and that Monkey the do food eat is not a well-formed sentence. Children learn these things in stages, but at all stages, the learning is implicit, a function of input and interaction.

Some approaches to language study are focused on a different kind of rules: rules that people are taught in school in order to speak or write in a certain way. Consider the two sentences in (3-4), both of which describe the picture below.

(3) That’s the cat the baby was lying next to.

(4) That’s the cat next to which the baby was lying.

At some point in your life, someone may have told you a “rule” about English: “You can’t end a sentence with a preposition.” But I just did! In sentence (3), to is a preposition, and it’s at the end of the sentence. Does this sentence sound bad to you? Does it sound like it’s not English? I doubt it.

Sentence (4) is the “correct” version of this sentence according to the can’t-end-sentence-with-preposition rule. Which sentence sounds more natural? To my ear, (4) sounds awkward and super-formal, while (3) sounds just…normal. Moreover, if I were going to describe the cat pictured above, I would automatically produce sentence (3), not sentence (4). Clearly, English speakers (like me) have some kind of rule that allows for sentences like (3).

What kind of rule, then, is “Never end a sentence with a preposition”? It’s a rule about how someone thinks English should be spoken; about what kinds of structures in English are supposedly better or worse than others. We call these prescriptive rules. They describe some idealized state of English, which someone decided was better than others. But the fact that someone had to tell you never to end a sentence with a preposition illustrates precisely the fact that you have a rule in your head that allows you to end a sentence with a preposition! If no English speakers ended sentences with prepositions, there would be no need for anyone to tell them not to do it!

The prescriptive rule is meant to correct what English speakers naturally do. Why is it “bad” or “wrong” to end a sentence with a preposition? Can you think of any good reasons other than that someone told you so? I’ll wait…

In contrast, our approach to grammar will be descriptive: we want to know what patterns English speakers actually produce when they generate English sentences. By definition, a “native English speaker” has acquired the rules of English; those are the rules we need to describe in order to describe English.

KEYWORDS

- prescriptive: prescribing how language should be

- descriptive: describing how language actually is

Prescriptive rules can have their place—namely, if you are trying to impress someone who cares about following them! But they are not especially useful for a descriptively adequate approach to grammar. To illustrate the difference between prescriptive and descriptive rules, consider an analogy. How would you describe what happens in a human during the physical act of chewing? Here is a definition from Wikipedia:

In a nutshell, you move your jaw open and shut in order to use the teeth to grind down food. Crucial question: Is your mouth open or shut while you chew? Probably, at least if you have been raised in the US, you will have been taught to keep your mouth closed while you chew. But the description above doesn’t say anything about it. That’s because the act of chewing can be done either way, with the mouth open or closed, and the chewing still gets done.

In what sense, then, is “Chew your food with your mouth closed” a rule? It’s a rule about manners, etiquette—social evaluation. It’s not a rule that describes anything inherent or fundamental about the anatomical act of chewing. And considering all the scolding that goes into enforcing this “rule,” it’s probably safe to assume that the natural state for humans to chew in involves an open mouth. If everyone naturally chewed with their mouths closed, why would we have to make such a big deal out of it?

Coming back to language: violating prescriptive rules of English means you’re just speaking English in a way that’s different from the way someone else wants you to speak. Violating descriptive rules, on the other hand, means you’re probably not speaking grammatical English at all.

Now come back to grammaticality. Remember our example sentences in (3-4) above, concerning the position of the preposition “to.” Both (3) and (4) are grammatical sentences in English: they follow the descriptive rules of English grammar. A native speaker could say either, and upon hearing either, a native speaker wouldn’t be left thinking, “But that person isn’t speaking English!” Maybe one could say, “But it’s incorrect! It ends a sentence with a preposition!” Please discard, for the purposes of this class, the notion of a sentence being “correct” or “incorrect”! These are terms typically applied within prescriptive frameworks. Chewing with your mouth open is not “incorrect” any more than sneezing without covering your nose is, or speaking English instead of Chinese is. Might it fail to accomplish some social goals, or garner some negative social evaluations? Perhaps. But that is about society’s impression of chewing, not chewing itself. So it is with language.

A descriptive approach is so important for us because we want to be able to describe the English language in all of its many manifestations–including English’s many dialects. Consider the following sentences:

(5) is a popular lyric by Beyoncé (“Single Ladies”). Would you say that this sentence is “correct”? Would you say that it is “grammatical”? If not, how is it possible that Beyoncé produced it? Is Beyoncé not a native speaker of English? This sentence contains a feature of African American English, a well-documented dialect of English that has structural differences from “Standard American English.” Sentences containing African American English are often called “incorrect,” but they are perfectly grammatical to speakers of African American English. What makes (5) any less “correct” than the version in (6)? They are both produced by native speakers of English, and interpretable by native speakers as being English.

Consider another more recent example, this one from Childish Gambino:

This is the same feature as in the Beyoncé example–it’s a regular, systematic feature of AAE. Just as we would not say that speaking English is “correct” while speaking German is “incorrect,” it doesn’t make sense to say that speaking one dialect of English is “correct” while speaking others is “incorrect.” There is no scientific basis on which to say that AAE, or any other dialect, is “incorrect.” Instead, the question for us is: is the sentence grammatical? If so, we want to be able to account for it in our description of English.

Now, consider the sentences below in (8-9).

(8) contains the same words as (5), while (9) contains the same words as (6). But these sentences are ungrammatical to <em>all speakers of English</em>, regardless of dialect. No speaker of any dialect of English would produce either sentence. If one were in a Beyoncé song, we would think she was taking extreme artistic license with English!

Dialect differences highlight the fact that intuitions about what is grammatical or ungrammatical differ across speaker groups—what is grammatical for a speaker of Standard American English may seem ungrammatical to a speaker of Appalachian English. One group’s “normal” is another group’s “odd.” Intuitions can also differ across individual speakers—the use of a verb that sounds perfectly good to me may sound not-so-great to you. Here’s an example of something I thought sounded “normal”:

I’ve had students say that this sounds weird to them. They said that “homework” cannot be plural in this way, and instead I should say “homework assignments.” Well, for them this may be ungrammatical, but it sounds great to me—otherwise I wouldn’t have said it! In this class we will often probe our own intuitions about what is and is not grammatical in English, but we will not always agree—and that is okay. The English language is not a cut-and-dry system with clear-cut answers, because no one sat down and had a meeting to create it that way. As a natural system, it is constantly changing, it differs from group to group and person to person, and we will never achieve a “perfect” analysis of it. Lucky for us, this makes our task much more interesting!

3. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 1, Basic Unit

Complete before moving on to the next unit!