Ch. 3: Trending Topics

By now you may recognize the critical point that the substance use, misuse, and SUD arena is a dynamic, constantly changing scene and what we think we know about the topic at any point in time is likely to need review again in the future. In this chapter, we examine a couple of trending topics—topics where practitioners, scholars, investigators, and others may not share a common viewpoint. The most enduring point of contention and debate concerns the way the addiction or substance use disorders are viewed. The second concerns the appropriateness of adopting harm reduction approaches to solving the problems associated with substance use and misuse. Third, involves adoption of a recovery orientation in thinking about substance misuse and substance use disorders, particularly in terms of how programs, services, and policies are designed. Note that some contents presented in this chapter are both adapted from and informed the writing of an introductory chapter by Begun and Murray (in press), to the Handbook of Social Work and Addictive Behavior from Routledge.

Defining Addiction

There involved in defining substance misuse and SUD than the clinical diagnostic protocols presented in the DSM-5 and ICD-11. As a start, consider the American Society of Addiction Medicine policy statement defining addiction (ASAM, 2011):

Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behavior and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death (p. 1).

Important aspects of this definition are recognition of:

- the impact of addiction on biological, psychological/emotional, social, interpersonal, and spiritual aspects of life;

- the brain-behavior nexus in the development and maintenance of addictive behavior;

- the common experience of cyclical relapse and remission, and

- the potential for problem progression.

The ASAM definition reflects a “disease model” perspective—a model popular in the United States and many other areas, but not without controversy and critics, particularly in other parts of the world.

Original disease model of addiction. The original disease model of addiction emerged during the 1950s and 1960s regarding alcoholism, viewing addiction as a primary disease, not secondary to other psychological conditions (Hartje, 2009). The original disease model of addiction was hailed as an important, less stigmatizing alternative than the prevailing moral model that placed blame on individuals for their addiction and deemed them deserving of its consequences and punishment (Thombs, 2009). Viewing addiction as a disease, instead, allowed the person to be seen as the “victim” of an illness, deserving of compassionate care and medically supervised treatment (Thombs, 2009). In the disease model, an individual’s choice to initially engage in substance may have been freely made; however, once initiated, the disease could take over: “intense cravings are triggered via physiological mechanisms, and these cravings lead to compulsive overuse. This mechanism is beyond the personal control of the addict” (Thombs, 2009, p. 561).

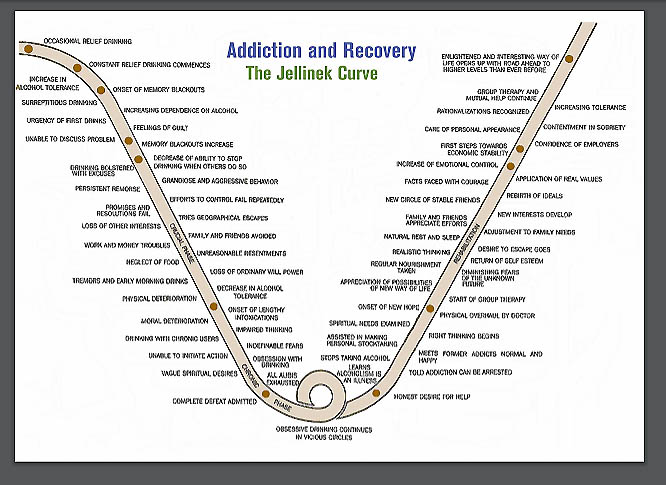

Research by E. Morton Jellinek was credited with providing early support for a disease model of addiction (Hartje, 2009). Based on a non-random sample of surveys completed by 98 men responding to an Alcoholics Anonymous newsletter, later expanded to include 2,000 histories, Jellinek (1952) identified four progressive phases of the disease: the prealcoholic symptomatic, prodromal, crucial, and chronic phases. The “Jellinek Curve” reflects how specific behaviors and experiences relate to the disease’s progression and recovery—its very design reflects the perception of a person “hitting bottom” before being able to recover from addiction (from https://www.in.gov/judiciary/ijlap/files/jellinek.pdf).

Despite methodological weaknesses in the evidence, the original disease model became popular with many practitioners and Alcoholics Anonymous programs, introducing significant implications:

- alcoholism was viewed as a chronic, progressive, incurable disease;

- professional treatment was specified as necessary to control this incurable disease;

- abstinence was viewed as the only defense against recurrence and the only reasonable goal for a person with this disease;

- substituting a different drug for alcohol was expected to manifest the same disease symptoms and progression (Hartje, 2009).

The original disease model and principles have greatly influenced assessment and treatment practices over the past 60 to 70 years. There exist several points around which the original disease model of addiction has been challenged.

Heterogeneity challenge to the original disease model. Longitudinal studies documenting the natural course of alcoholism demonstrated significant inconsistencies with a disease progression premise: multiple patterns were observed among men still alive 60 years after beginning the study, including continued alcohol abuse, stable abstinence, and return to asymptomatic/controlled drinking (Vaillant, 2003). Tremendous individual variation exists in patterns of addictive behaviors, as well as the severity of problems experienced by individuals at different points in time. Jellinek (1952) admitted that his was an “average trend” model in which individuals do not necessarily exhibit all of the symptoms associated with a phase, may differ in the sequencing of symptoms, and may differ in the duration of each phase; furthermore, “nonaddictive alcoholic” individuals may experience the identified negative consequences of alcoholism without experiencing a loss of control over drinking, and women may experience the disease differently.

This high degree of variability (heterogeneity) in expression called into question the perspective that alcoholism (or any substance use disorder) represents a single disease. Emphasis on the addiction/dependence end of the continuum of substance misuse “has resulted in a myopic view of substance abuse problems that has characterized them as progressive, irreversible, and only resolved through treatment” (Sobell, 2007, p. 2). Observed heterogeneity has informed the diagnostic schedules’ differentiations: different substances (and addictive behaviors such as gambling disorder) have distinct diagnostic codes. If “addiction” were a single uniform event there would be no need for multiple diagnostic categories—or different intervention strategies.

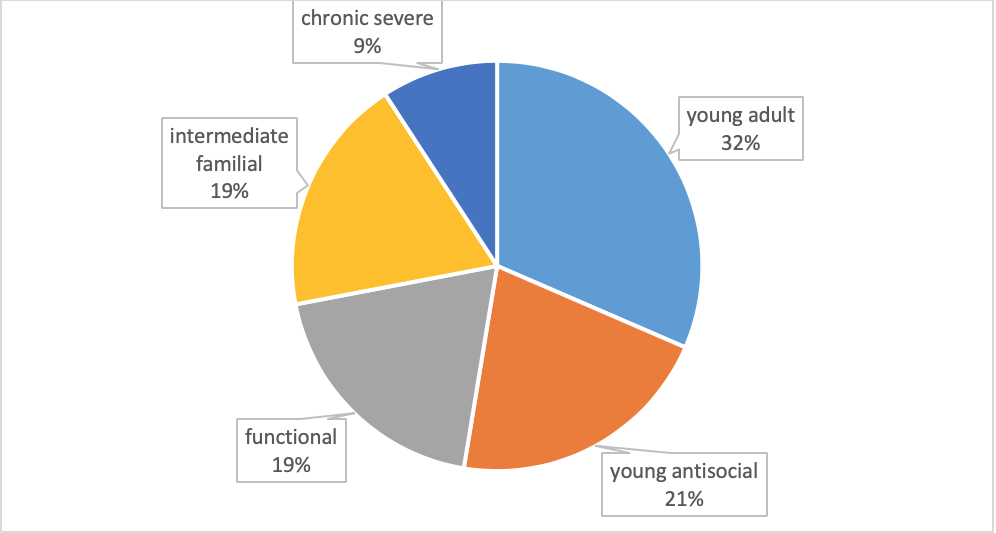

Subtypes versus stages of disease. There exist marked differences in how substance misuse/SUDs are expressed even within a single substance type. Challenging Jellinek’s stage model of alcoholism, for example, is evidence of heterogeneity in “types” of alcoholism derived from a national sample (U.S.). The investigators based their typology on clinical characteristics of individuals meeting criteria for an alcohol dependence per the DSM-IV-R criteria that preceded the DSM-5 (Moss, Chen, & Yi, 2007). This analysis of U.S. National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) data led the authors to identify five “subtypes” of alcohol dependence, demonstrating clinical heterogeneity within the single diagnostic classification. The subtypes they identified were based on how participants clustered on diagnostic criteria, age of onset, family history, and presence of other co-occurring disorders. The five statistically determined clusters they identified were labelled: young adult, young antisocial, functional, intermediate familial, and chronic severe subtypes (see Figure 1). The groups demonstrated differences in their patterns of drinking, help-seeking, and response to intervention, as well. This study, based on a large, nationally representative sample reflected heterogeneity among persons engaged in a specific addictive behavior, and the wisdom of avoiding stereotypes about them—for instance, while the chronic severe subtype was the least common, it reflects a common stereotype of alcohol dependence.

Figure 1. Subtypes of alcoholism (based on data from Moss, Chen, & Yi, 2007).

Treatment and the disease model. Additional important challenges to the disease model of addiction appear in the literature. Asserting that formal treatment for addiction is necessary has been challenged by evidence that many individuals experience significant, long-lasting improvement without engaging in formal treatment—sometimes referred to as “natural recovery” or “self-change”—typically, persons whose alcohol misuse is not of the most severe dependant nature (Sobell, 2007). Little is known about natural recovery in other substance misuse, though some evidence for its existence appears in the literature (e.g., Chen, 2006; Erickson & Alexander, 1989; Price, Risk, & Spitznagel, 2001). Possibly, the necessity for engaging in formal treatment varies by individual, severity of the problem, and characteristics of the substances or addictive behaviors involved.

Treatment and the disease model. Additional important challenges to the disease model of addiction appear in the literature. Asserting that formal treatment for addiction is necessary has been challenged by evidence that many individuals experience significant, long-lasting improvement without engaging in formal treatment—sometimes referred to as “natural recovery” or “self-change”—typically, persons whose alcohol misuse is not of the most severe dependant nature (Sobell, 2007). Little is known about natural recovery in other substance misuse, though some evidence for its existence appears in the literature (e.g., Chen, 2006; Erickson & Alexander, 1989; Price, Risk, & Spitznagel, 2001). Possibly, the necessity for engaging in formal treatment varies by individual, severity of the problem, and characteristics of the substances or addictive behaviors involved.

Abstinence only prescription based on disease model. Viewing abstinence from substance use as the only defense against “disease” recurrence and the only reasonable goal for a person experiencing a substance use disorder has been challenged. Complete abstinence from all psychoactive substances is at one end of a continuum in treatment strategies, commonly applied in U.S. medical practice (Glenn & Wu, 2009). A debated position is that the continuum of recovery includes controlled substance use, including the type of substance which a person previously used problematically. Between these positions is a question of whether psychoactive medications used to treat substance use disorders reflects recovery or is only a prelude to recovery not achieved until these medications are no longer needed. This question relates to an assertion that substituting one substance for another, despite its being safer, more controlled, or reducing harm, simply maintains the disease rather than offering a cure.

Abstinence only prescription based on disease model. Viewing abstinence from substance use as the only defense against “disease” recurrence and the only reasonable goal for a person experiencing a substance use disorder has been challenged. Complete abstinence from all psychoactive substances is at one end of a continuum in treatment strategies, commonly applied in U.S. medical practice (Glenn & Wu, 2009). A debated position is that the continuum of recovery includes controlled substance use, including the type of substance which a person previously used problematically. Between these positions is a question of whether psychoactive medications used to treat substance use disorders reflects recovery or is only a prelude to recovery not achieved until these medications are no longer needed. This question relates to an assertion that substituting one substance for another, despite its being safer, more controlled, or reducing harm, simply maintains the disease rather than offering a cure.

The word “sobriety” originally, historically implied temperate, moderated indulgence, not necessarily complete abstinence—an abstinence interpretation emerged during the 1900s (Glenn & Wu, 2009). Evidence since the 1970s indicates that some individuals achieve controlled drinking despite having previously engaged in an “out-of-control” drinking pattern, contrary to “the prevailing belief that any alcohol consumption causes an inevitable loss of control over one’s alcohol use” (Klingemann, 2016, p. 436). The debate about “controlled drinking,” “reduced-risk drinking,” and “moderation management” continues, and it is unclear how the evidence for and against it might apply to other substances and addictive behaviors. On the issue of the use of pharmacotherapy to assist in controlled drinking, recent meta-analysis concluded that three medications showed controlled drinking outcomes superior to a placebo, but the effects were small and inconsistent across studies (Palpcuer et al., 2018). With or without medication, reduced-risk drinking (RRD) is seen in many Western European countries as one pathway out of addiction, and a legitimate treatment goal (Klingemann, 2016). As previously noted, the ability to engage in controlled use following a substance use disorder may vary by individual, severity of the problem, and characteristics of the substances or addictive behaviors involved.

Closely associated with the abstinence issue lies an additional point of contention with the final disease model of addiction, the expectation that substituting a different substance for the primary addictive behavior (e.g., misuse of alcohol, cannabis, or opioids) simply continues manifestation of the same disease of “addiction” where the symptoms persist, as does the pattern of disease progression. This stance contributes to the hesitancy expressed by some practitioners that medically assisted treatment (MAT) and the use of pharmacotherapies to treat substance use disorders maintains the (incurable) disease rather than treating it. Evidence of the effectiveness of these approaches for many persons, including eventual weaning from medication, contradicts this contention.

Closely associated with the abstinence issue lies an additional point of contention with the final disease model of addiction, the expectation that substituting a different substance for the primary addictive behavior (e.g., misuse of alcohol, cannabis, or opioids) simply continues manifestation of the same disease of “addiction” where the symptoms persist, as does the pattern of disease progression. This stance contributes to the hesitancy expressed by some practitioners that medically assisted treatment (MAT) and the use of pharmacotherapies to treat substance use disorders maintains the (incurable) disease rather than treating it. Evidence of the effectiveness of these approaches for many persons, including eventual weaning from medication, contradicts this contention.

Loss of Control Concept. The original disease model of addiction expressed another point with which scholars and practitioners have taken issue: applying “loss of control” as a defining criterion. The prior moral model attributed individuals’ use/misuse of alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs to moral failure or personality weakness, holding them “personally responsible for creating suffering for themselves and others” (Thombs, 2009, p. 561). The original disease model, as previously discussed, did not take a position on a person’s initial decision to use a substance, but argued that the “disease” may take over, eventually rendering an individual helpless to control the behavior. Heather (2017) argued against the “compulsion” aspect of the disease model where addictive behavior “is said to be carried out against the will,” and “marks the turning point from normal, recreational drug use to addictive drug use” (p. 15). His counter-argument does not support a moral failure/blame stance toward addiction; instead, he emphasized the power of environmental, contextual, and reinforcement paradigms operating to influence behavioral choices related to continued engagement in substance misuse (or other addictive behaviors). One problem with the loss of control concept is that individuals may reframe it in terms of, “I can’t help myself,” excusing themselves from taking responsibility for the behavior or taking steps toward recovery.

Contemporary brain disease model and biopsychosocial perspective. As previously noted, recognition of the brain-behavior nexus in the development and maintenance of addictive behavior is important and necessary to understanding, intervening around, and recovery involving addictive behavior and related problems. Evidence concerning the neurobiology of substance use and mechanisms involved in the transition to substance use disorders has expanded in many directions over the past two decades, contributing to a widening variety of treatment and prevention intervention strategies (Volkow & Koob, 2015; Volkow, Koob, & McLellan, 2016).

Contemporary brain disease model and biopsychosocial perspective. As previously noted, recognition of the brain-behavior nexus in the development and maintenance of addictive behavior is important and necessary to understanding, intervening around, and recovery involving addictive behavior and related problems. Evidence concerning the neurobiology of substance use and mechanisms involved in the transition to substance use disorders has expanded in many directions over the past two decades, contributing to a widening variety of treatment and prevention intervention strategies (Volkow & Koob, 2015; Volkow, Koob, & McLellan, 2016).

Proponents of a contemporary brain disease model of addiction argue that: “After centuries of efforts to reduce addiction and its related costs by punishing addictive behaviors failed to produce adequate results, recent basic and clinical research has provided clear evidence that addiction might be better considered and treated as an acquired disease of the brain” (Volkow, Koob, & McLellan, 2016, p. 364). The U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse applies the following definition of addiction:

“Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences. It is considered a brain disorder, because it involves functional changes to brain circuits involved in reward, stress, and self-control, and those changes may last a long time after a person has stopped taking drugs. Addiction is a lot like other diseases, such as heart disease. Both disrupt the normal, healthy functioning of an organ in the body, both have serious harmful effects, and both are, in many cases, preventable and treatable. If left untreated, they can last a lifetime and may lead to death” (NIDA, 2018).

Chronic, relapsing diseases like diabetes or high blood pressure often have a strong behavioral health component—just as substance use disorders. While these disease conditions may worsen over time, the outcome is not immutable—outcomes can be affected by behavioral health interventions, as well as self-directed changes in behavior and/or environment.

Biopsychosocial

Biology and psychology intersect where substances altering the brain’s reward and emotional circuits influence individuals’ experiences, learning, memory, affect, executive function, decision-making, expectancies, withdrawal symptoms, and cravings, with profound implications for continued engagement in addictive behavior, as well as strategies for changing addictive behavior patterns. Understanding brain-behavior processes is necessary; however, this alone does not impart sufficient knowledge. Biological and psychological processes do not occur in a vacuum, but within complex, impactful social contexts and physical environments. For example, evidence that early exposure to alcohol and other substance misuse increases the odds of developing a substance use disorder later in life (Odgers et al., 2008) invokes mechanisms of multiple types: changes to the brain (biology); learning, social learning, and expectancies (psychology); social norms and access (social context/environment). Not only does recovery occur within social contexts (Heather et al., 2018), biological, psychological, and social interventions all may play a role. Furthermore, social and psychological interventions can influence neurobiological processes (Volkow, Koob, & McLellan, 2016); biology does not confer destiny but has a powerful iterative relationship with the other domains. Viewing addictive behaviors from an integrated biopsychosocial framework is required and reflected throughout this book.

Harm Reduction

A somewhat contested topic related to substance misuse and related problems is harm reduction. First appearing in the literature during the late 1980s and early 1990s, the term “harm reduction” was used to describe attempts to reduce adverse consequences associated with substance misuse, without necessarily eliminating substance use (Single, 1995). Two general levels of harm reduction effort emerged in the literature: clinical practice and policy interventions. Underlying harm reduction is recognition of the potential harms associated with engaging in addictive behavior (e.g., substance misuse or problem gambling), as well as knowing that some individuals will continue to engage in these behaviors, at least for an unknown length of time, despite the potential for harms to self and others. “The essence of the concept is to ameliorate adverse consequences of drug use while, at least in the short term, drug use continues” (Single, 1995, p. 287).

Examples of harm reduction strategies at the program/policy level that have at least some support from research evidence are:

- clean needle exchange programs,

- medically supervised injecting facilities (more common in other countries than the U.S.),

- heroin-assisted treatment (more common in other countries than the U.S.),

- distribution of fentanyl testing strips, and

- wide public distribution of opioid overdose reversal kits (Narcan).

These strategies can reduce the risk of infectious disease transmission and drug overdose, among other potential harms (Drucker et al., 2016).

Examples of harm reduction practices at the clinical level include:

- nicotine replacement therapy to reduce harms associated with smoking tobacco products, and

- medication-assisted treatment (MAT) involving opioid substitution drugs (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine) to reduce harms associated with use of unregulated “street” drugs.

While harm reduction as a public health and social work strategy makes intuitive sense on the surface, controversy revolves around philosophy and implementation, led to some degree by a misunderstanding of harm reduction (Drucker et al., 2016). One argument against harm reduction strategies is that it may be mis-perceived as sanctioning the problematic behavior. The evidence on this is mixed, however. For example, while zero-tolerance/abstinence-based messaging was more effective in curbing college students’ future drinking in several studies (Abar, Morgan, Small, & Maggs, 2012; LaBrie, Boyle, & Napper, 2015), in another, this was true only among students who currently consumed two or fewer drinks per week; harm reduction messaging outcomes were more favorable among students currently engaged heavy drinking (Napper, 2019). Thus, the anti-harm reduction argument that it seems to sanction the behavior, thereby contributing to the problematic behavior, is only partially supported by evidence. An argument that harm reduction (reducing the negative consequences) interferes with motivation to seek treatment and/or quit engaging in the problematic behavior is also countered with the argument that, as a result of engaging in harm reduction programming, individuals may then become encouraged to engage in treatment to reduce or cease substance misuse (Drucker et al., 2016). An argument against nicotine or opioid replacement therapies is that the person continues to experience substance dependence. However, use of these therapies may allow the individual to gradually become weaned from dependence in a controlled manner, supported by behavioral therapies. While this is argument is offered in support of e-cigarettes/vaping as a harm reduction tool, evidence is mounting that significant risks of harm are associated with these devices (including injury from malfunctions/battery problems, chemical exposure not being reduced as much as advertised, worsening of the nicotine dependence, and poisoning of children and pets from the liquid nicotine).

While harm reduction as a public health and social work strategy makes intuitive sense on the surface, controversy revolves around philosophy and implementation, led to some degree by a misunderstanding of harm reduction (Drucker et al., 2016). One argument against harm reduction strategies is that it may be mis-perceived as sanctioning the problematic behavior. The evidence on this is mixed, however. For example, while zero-tolerance/abstinence-based messaging was more effective in curbing college students’ future drinking in several studies (Abar, Morgan, Small, & Maggs, 2012; LaBrie, Boyle, & Napper, 2015), in another, this was true only among students who currently consumed two or fewer drinks per week; harm reduction messaging outcomes were more favorable among students currently engaged heavy drinking (Napper, 2019). Thus, the anti-harm reduction argument that it seems to sanction the behavior, thereby contributing to the problematic behavior, is only partially supported by evidence. An argument that harm reduction (reducing the negative consequences) interferes with motivation to seek treatment and/or quit engaging in the problematic behavior is also countered with the argument that, as a result of engaging in harm reduction programming, individuals may then become encouraged to engage in treatment to reduce or cease substance misuse (Drucker et al., 2016). An argument against nicotine or opioid replacement therapies is that the person continues to experience substance dependence. However, use of these therapies may allow the individual to gradually become weaned from dependence in a controlled manner, supported by behavioral therapies. While this is argument is offered in support of e-cigarettes/vaping as a harm reduction tool, evidence is mounting that significant risks of harm are associated with these devices (including injury from malfunctions/battery problems, chemical exposure not being reduced as much as advertised, worsening of the nicotine dependence, and poisoning of children and pets from the liquid nicotine).

Recovery Orientation

A recovery orientation refers to a host of values, beliefs, and behaviors related to how individuals engage in and experience the process of recovery from a SUD (Bersamira, in press). The recovery orientation is fundamentally informed by the individuals’ own definitions of the problems, solutions, and subjective experiences, rather than those being imposed by others. Built into this orientation are issues such as having individuals define for themselves what constitutes “recovery”—this may or may not include abstinence as a goal, for instance. Another aspect has to do with adopting a holistic view where individuals’ recovery is embedded in a context of all life structures, functions, and wellness, including their future growth and development as a person, not just changes in past substance use/misuse behavior (Kaskutas et al., 2014). Thus, recovery does not simply mean achieving the absence of disease, it means promoting wellness across all life domains.

A recovery orientation refers to a host of values, beliefs, and behaviors related to how individuals engage in and experience the process of recovery from a SUD (Bersamira, in press). The recovery orientation is fundamentally informed by the individuals’ own definitions of the problems, solutions, and subjective experiences, rather than those being imposed by others. Built into this orientation are issues such as having individuals define for themselves what constitutes “recovery”—this may or may not include abstinence as a goal, for instance. Another aspect has to do with adopting a holistic view where individuals’ recovery is embedded in a context of all life structures, functions, and wellness, including their future growth and development as a person, not just changes in past substance use/misuse behavior (Kaskutas et al., 2014). Thus, recovery does not simply mean achieving the absence of disease, it means promoting wellness across all life domains.

Many individuals and professionals actively engage in advocacy related to a general recovery-oriented movement, promoting recovery-oriented services and policy (Bersamira, in press). This orientation includes engaging indigenous and professional services and relationships in supporting individuals’ long-term recovery (and their families), as well as shaping the culture of communities and policy (White, 2008). For example, peer support systems are often an integral aspect honored and incorporated in a recovery orientation: peers being others who have lived the experience and found their own pathways to recovery. In other words, recovery-oriented systems of care differ quite markedly from traditional treatment systems: their services are more person-centered, self-directed, and strengths-based (Bersamira, in press).