Pantheon, UNKNOWN DESIGNER, Classical Roman, ROME, Italy, 118 A.D.

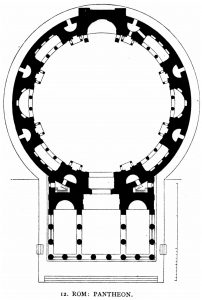

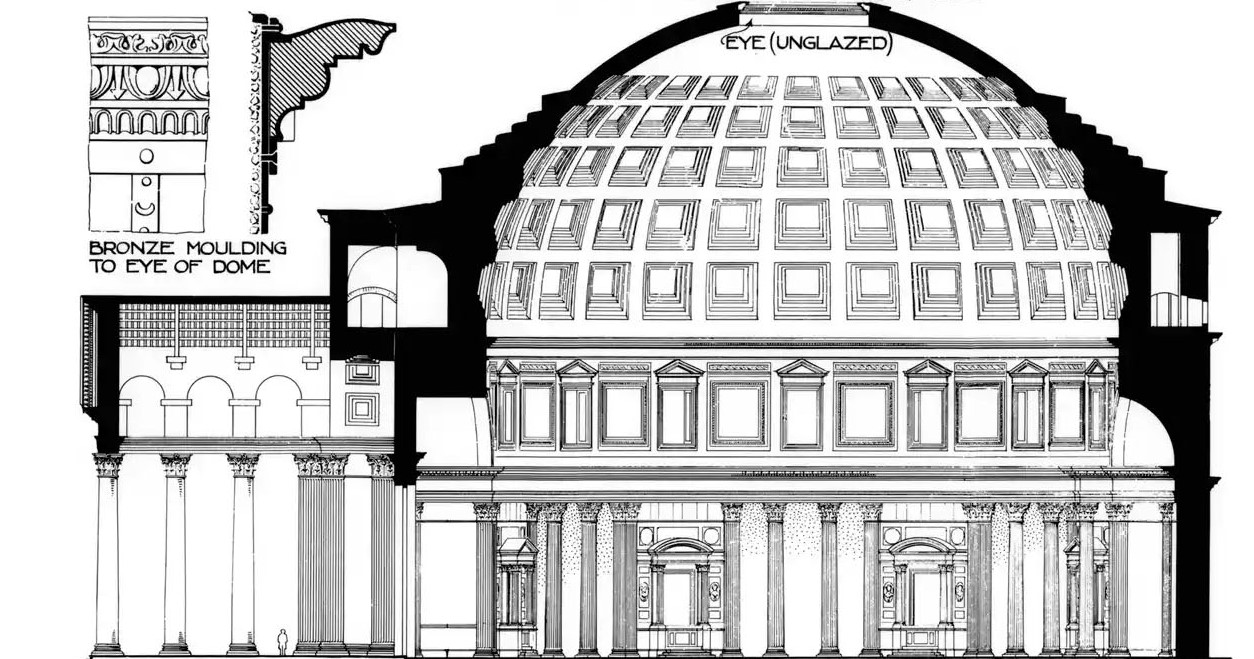

Plan, elevation, section, and cross section of the Pantheon

Image 1: Front portico with pediment of Pantheon and obelisk

The skyline of Rome is not defined by skyscrapers or bridges; it is a city of domes (image 2). The many domes one sees in the skyline is a representation as Rome is the center of the Christian world, more specifically the center of the Catholic world. One of the more demure domes in the skyline is one with great longevity and an icon for the city. Today we understand the Pantheon as a marvelous example of antiquity that remains amongst the contrast of the contemporary streets that have evolved today into the modern city of Rome.

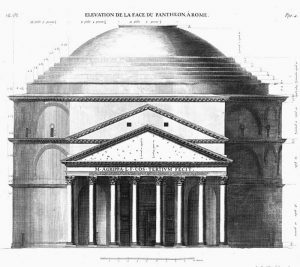

The building exudes a GENIUS LOCI, exuding the essence of the Classical Roman Empire from 2000 years ago. Today the Pantheon is a Christian church and tourist attraction, but it was originally designed and built as a pagan TEMPLE. The PLATONIC SOLIDS that define the building are a cylinder. In addition, embedded within the cylinder is half of a sphere, which is the dome, and an additive cube to define the PORTICO, emphasizing the main entry. The portico is covered with a PEDIMENT, triangular cap to a temple. The pediment is a PRECEDENT established from Classical Greek and Roman cultures and an icon that is translated many times throughout history on a multitude of different building types, not always religious.

In Classical Roman times, developing research articulates an orthogonal organization of the city around the Pantheon. Preceding the building would have been the clear extents of a rectangular FIGURAL VOID of the FORUM accentuating the frontal quality reinforced by the portico. The density of the Classical Roman urban context includes residential, commercial, religious, entertainment and many other types of constructions. Today the forum has been amended with a void not as clearly defined, yet still exists changed by the contemporary context of the city. An OBELISK is featured near the middle of the figural void preceding the building (image 1). Obelisks were created during Egyptian times, many erected in proximity to monumental structures. Many obelisks are carved with Egyptian iconography and capped today with the cross symbolizing the conquering of Christianity over other religions. The Classical Romans transported obelisks across the Mediterranean Sea and placed them at important sites in the city of Rome, such as temples or a circus. About 1500 years after the Classical Roman era, the Romans will again move the obelisks to highlight the Baroque reorganization of Rome.

Image 2: Skyline of Rome featuring domes

Moving through the building, one first experiences the semi-opened portico of CORINTHIAN COLUMNS of the building (image 3). A special quality of the Pantheon is the one door and one window. The scale of the door gives you a clue from the start of the monumental scale of the building (image 4). Continuing forward through the door, the interior is a cylinder capped with a dome (half sphere) hovering above. A section reveals the walls are thick, a clue to structural challenges and limitations of Classical Roman constructions, more to be discussed later.

Image 3: Corinthian columns at Pantheon portico

Image 4: Pantheon entry showing the massive scale of a door

The plan is simple, a circular interior with a porch defining entry into the circle. It’s a similar organization to Santa Costanza with a much larger portico. This creates a hybrid between the radial organization of Santa Costanza and the axial organization with the larger scale of the portico at the Pantheon. The interior is defined by the CELLA featuring seven statues of seven different gods. The Romans exploited structural innovations and materiality to create vast interior spaces. At the Pantheon, the interior cella walls are the same as the exterior walls of the building, creating a vast open interior space with a massive dome floating above. Today the building has been transformed to a Christian CHURCH, Christian statues, imagery and icons replacing the pagan iconography. At the opposite end of the entry door is the ALTAR, the focus of the Christian religious ceremony.

The wall of the cella is defined by seven NICHES (image 5) holding the statues tucked into the POCHE of the walls. The poché is the thickness between two surfaces of a wall that can be carved. Because the walls at the base of Pantheon are almost twenty feet wide (see shaded area and scale on section drawing), the designers were able to remove mass from the walls and create small spaces to incorporate decorative details. The walls were thick at the base of the Pantheon to help resist LATERAL THRUST forces, the tendency of the forces of a dome or an ARCH to kick out at the base. Lateral thrust was being created by the massive 142 foot DOME hovering above the entire interior. The Romans were able to overcome the structural challenge of lateral thrust by creating thick walls at the base. The materiality of the walls and dome is of CONCRETE. Advantages of concrete are that it can be shaped and molded easier than working in stone and it is a lighter building material. The Pantheon is the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world for over a millennia.

Image 5: Main altar at Pantheon showing niches with statues

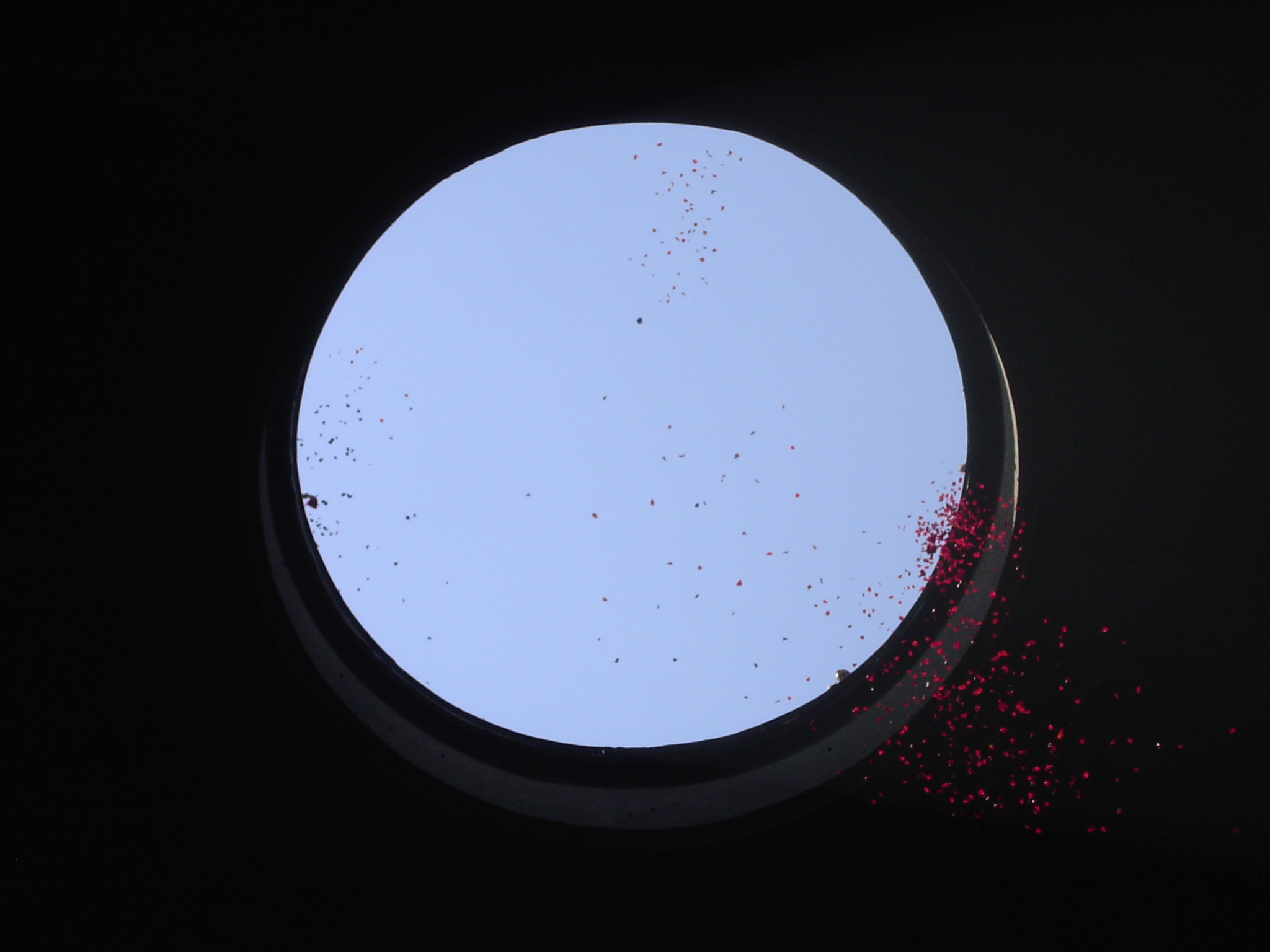

In addition to the axis present in plan from entry to altar, an AXIS MUNDI connects the heavens to the earth through the direct opening at the top of the dome. Axis mundi often relates to a religious or spiritual connection, though there are exceptions, such as at Knowlton Hall. This axis mundi works to create a MICROCOSM relationship within the Pantheon, possible through several different ideas. On a sunny day, light is entering the one window at the top of the dome (image 7). The light is incredibly dynamic in the space present as a moving beam of light. As the light moves throughout the day, what starts as a smaller spot of light on the wall (image 8), becomes a large spot on the floor (image 9). This beam or spot of light has an incredible presence in the space, contrasting to the surrounding darkness as this is the main source of light in the Pantheon. When the light is on the floor, and one walks into the spot of light, an instant connection with the heavens is felt. It is a powerful moment and relationship to the building.

Image 6: Oculus at Pantheon, see scale of human heads at rim throwing rose petals through oculus on Pentecost

Image 7: Beam of light reinforcing axis mundi

Image 8: Beam of light becomes a spot of light on the wall

Image 9: Spot of light at the floor reinforces connection of axis mundi, see scale of person

There are additional understandings of microcosm. First, the section embodies a sphere perfectly within the 142 foot width and height. There is a demure cupped dip in the center of the floor reminding one of this proportional relationship with four small drainage holes. The Romans were masters of water management in buildings and at the urban scale through AQUEDUCTS. The marble floor at the Pantheon is one of the best examples of Classical Roman floors that still exists today. The OCULUS (image 6) is the opening at the top of a dome, a window (no glass) open to the sky. The interiors are fantastically open to the environment: when it rains, there is a column of rain coming into the building. When it snows (not that often), snow twinkles into the interiors. As described before, on a sunny day, the light is tangibly present and dynamic, reinforcing an axis mundi. Though the Romans didn’t believe the sun was at the center of the universe, the oculus is a focal feature at the Patheon. More on the Roman’s understanding of the universe below.

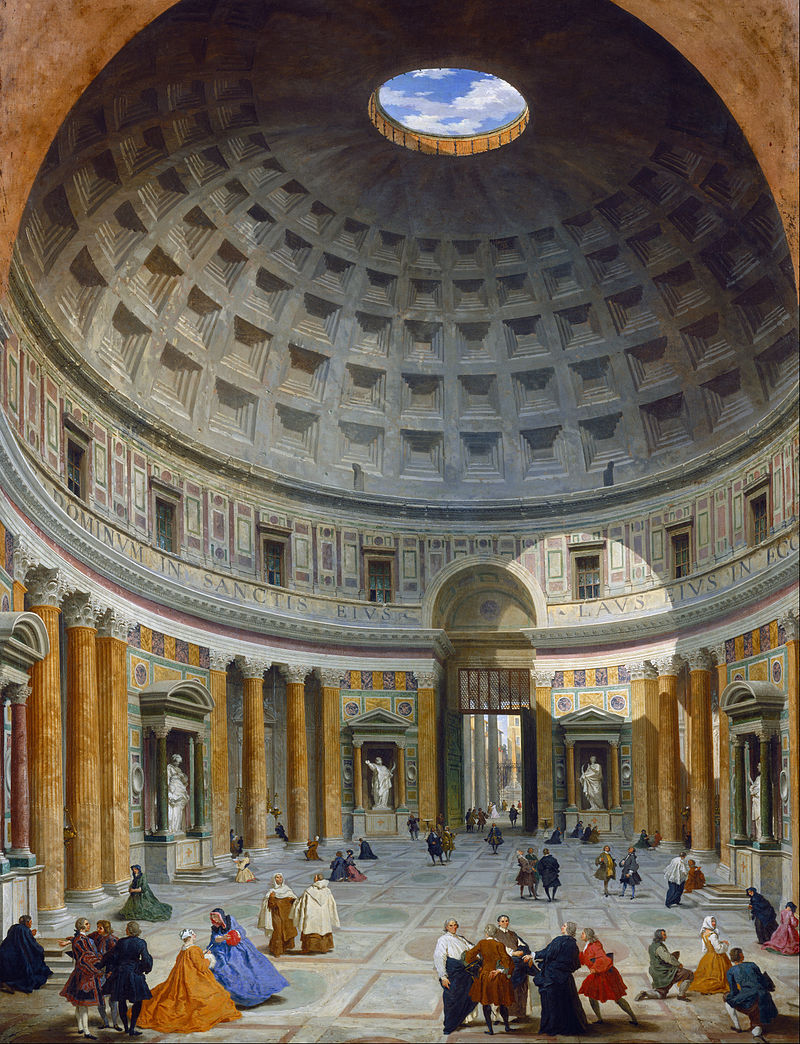

The interior ceiling of the dome is organized by COFFERS, a decorative pattern to a ceiling (image 10). There are many different iterations of coffers in architecture. The coffers at the Pantheon are in a particular shape and pattern that is unique. The coffers at the Pantheon are reinforcing a perspective in each individual coffer and in the larger dome making it appear larger and wider. The slight reduction of mass in the perspectival reiteration of square is DEMATERIALIZATION. The Romans were reducing mass in the dome in a decorative pattern through the coffers. The niches earlier noted can also be considered dematerialization. There is a specific pattern and meaning in the order of the coffers. Count closely and notice that there are five horizontal rows of coffers. These represent the five planets known to the Romans at the time (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars and Jupiter). There are twenty-eight vertical columns of coffers, days equal to a lunar cycle, representing the moon. The sun, the moon, and the five planets are all represented as a smaller iteration of the universe, a microcosm.

Image 10: Interior of the Pantheon painting by Giovanni Paolo Panini showing coffers and niches at Pantheon

Structural questions continue about how the oculus is functioning. If a typical essence of a dome is an arch spun three hundred and sixty degrees, and an arch requires all the parts of the arch to stand, how is the hole of the oculus possible? The dome at the Pantheon is a unique dome, a set of stacked rings working in compression allowing for the open oculus at the top. Lateral thrust is present in this type of dome, requiring the need for the mass of walls. The Romans created a system to build the largest unreinforced concrete span dome in the world and define a genius loci of the city epitomized in this building. It remains an important center and heart of the city today.

Media Attributions

- Plan Drawing of the Pantheon is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Elevation Drawing of the Pantheon © Antoine Desgodetz is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pantheon Section © Sir Bannister Fletcher is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Exterior Photo of the Pantheon © Aimee Moore

- View of the Rome Skyline © roamingwab is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Column Detail of the Pantheon © Aimee Moore

- Image of Pantheon Door © Aimee Moore

- Altar of the Pantheon © Aimee Moore

- View of the Occulus in the Pantehon © Aimee Moore

- The Occulus of the Pantheon © Aimee Moore

- View of the Directed Light of the Occulus © Aimee Moore

- Light Spot of the Panteon © Aimee Moore

- Interior of the Pantheon

a quality defining spirit of the place; it does not require a religious connotation

a religious building of a culture that worshipped multiple deities (pagan)

simplified three dimensional shapes extruded from basic shapes such as the circle or square

a larger porch added to a building; can be on one side only or wrap around to multiple sides

triangular cap to a temple originally, but also many other building types

a design that comes before and justifies later designs

lack of mass within a city, landscape or building

figural void (lack of mass) in an urban context in a Classical Roman city, plural is for a

a tall, thin, tapered stone, constructed of one solid piece of stone (no occupiable space within the structure)

column characterized by volutes (scrolls) and acanthus leaves

the interior most zone of a temple housing statues and important objects to the culture

religious building type related to Christianity, the worship of (one) God

recess or void carved into the thickness of a wall

the substance of a wall that can be carved into

the tendency of the forces of a dome or an arch to kick out at the base (of the dome or arch)

a curved structural element transferring forces from above to below

there are many ways domes can be constructed, one common dome is an arch rotated 360 degrees to create a dome

Common building material made of cement and aggregate allowing for many different forms and shapes to be created. Concrete is a malleable material poured into a wood or steel formwork. Once the concrete has cured, formwork is removed to leave the resultant concrete material that has hardened.

a Z axis (in the third dimension) connecting the heavens to the earth, often related to a religious or spiritual connection, though there are exceptions

smaller representation of a larger whole or system

designed and built during Classical Roman times, engineered waterways transporting water from long distances above ground to major cities such as Rome

opening at the top of a dome, but doesn’t always have to be dome, usually without any glazing (glass)

decorative pattern in a ceiling

reduction of mass in a structure