Baroque Replanning of Rome, DOMENICO FONTANA, Baroque, ROME, 1585 AD

The geography of the city of Rome is known for two major characteristics, the Tiber River and a city of hills. Two thousand years ago the Romans built predominantly in the valleys between the hills of Rome. Most Roman developments were within proximity to the Tiber and grew towards the east. As the city expanded and was defined as the center of the Christian world, a new urban organization was designed in the sixteenth century. Domenica Fontana is given main credit as the designer, though Pope Sixtus V also takes credit for the Baroque Roman Replanning. The redevelopment efforts were completed over many years. Though the urban reorganization finished primarily during Sixtus V’s reign, there were many other papal figures leading the culmination of these efforts.

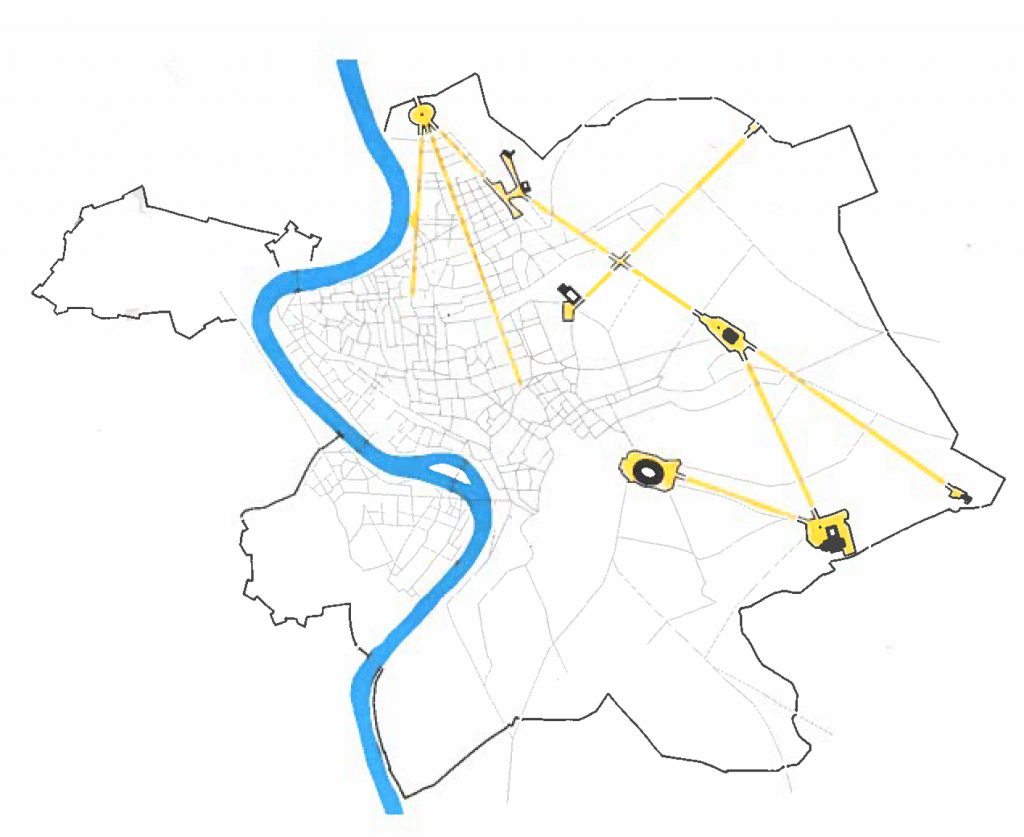

The earlier developments of the city were rather densely located in proximity to the Tiber River but extended to the Aurelian walls from Classical Roman times. Important in the Baroque replanning design was connecting a network of new churches expanding development to the east within the Aurelian walls, image 1 from Edmund Bacon’s Design of Cities. Major new figural voided radial axes (yellow lines on image 1) were carved out of the existing context of the city to highlight the development of the new Christian organization of the city within the Classical Roman walls. These developments were often located on or near the peaks such as Quirinale, Pincio and Esquiline hills.

Image 1: Plan of Baroque Replanning of Rome, yellow lines represent new axes carved through existing context of city connecting churches and urban sites

The political power in Rome at this time was held by the Christian church and the papacy. Therefore the reorganization featured new churches designed at the ends of the axes. At the northern end of the replanning efforts a trident of three axes were developed. The three axes are a reminder of the importance of the Trinity in the Christian faith. The axes started from the Piazza del Popolo, which was not designed in its current ovular shape until after 1750. The eastern most axis jogs from the Spanish Steps to Quirinale hill with a series of smaller churches including San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane and Sant’Andrea. The axis continues to Santa Maria Maggiore Basilica finalizing at two important religious sites near the Esquiline hill, Basilica of Santa Croce in Jerusalem and Santa Scala, both important sites on the pilgrimage route in Rome.

OBELISKS are added in front of the churches along the main axes. They create an axis mundi acting as a vertical marker at the end of the figural voided axes connecting long distances in the city through elevation. The connections become explicitly clear of the next site in the urban sequence of which you’re encouraged to continue experiencing. A reminder, these obelisks were original to Egypt and moved to Rome marking important locations in the Classical Rome context of the city. The Baroque Roman replanning now becomes the third iteration of the original Egyptian obelisks, now reused to redefine a Christian organization of the city.

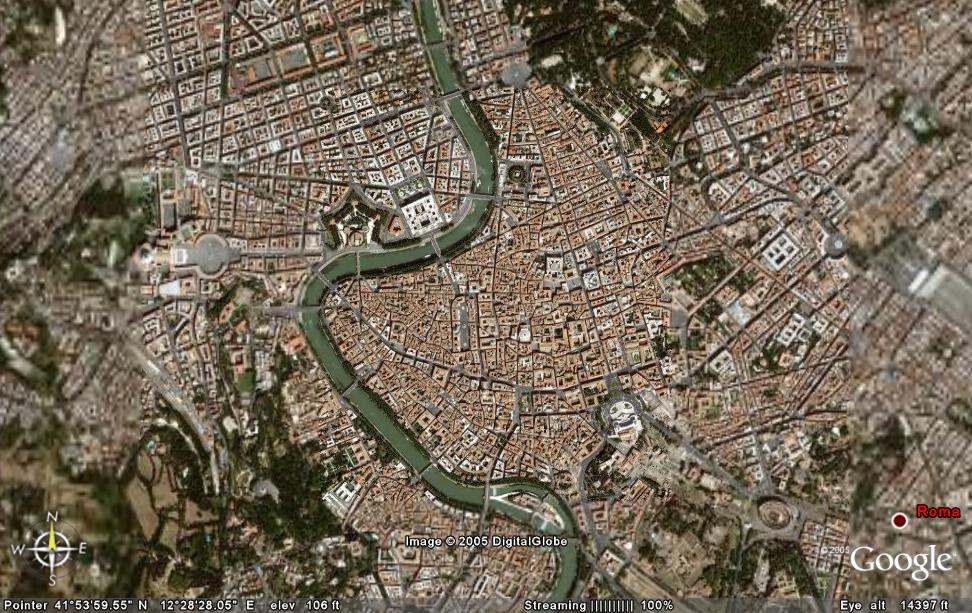

The city planning featured multiple Baroque characteristics. The sites were connected through the figural voided axes with an obelisk reinforcing a visual connection seen from long distances. The experience creates drama and heightens the emotions by featuring the topography in the urban planning. Anticipation builds scaling the hills of the city to reach the next focal point. The Baroque also features ambiguity through a multiplicity of centers, present with the various radial axes in the plan. Yet through the multiple centers, a spatial continuity weaves through the connected axes (image 2).

Image 2: Aerial view of Rome, showing axes from Baroque Roman replanning remaining in contemporary times

Perspective is exaggerated through the placement of buildings and obelisks at the tops of hills to reinforce to visual connection. Perspective was also exaggerated on streets such as Via del Corso (image 3), which has a similar building heights, proportion of buildings and datum of windows reading the majority of the street. The figural voided axes were carved through the existing context of the Roman to Renaissance era city of the urban fabric. Other cities such as London and Paris have been inspired to recreate this cohesive large scale urban reorganization, though perhaps not as cohesive as the scale of Rome. Defining and carving these axes through a city was quite powerful and monumental. It happened successfully in Rome because the Papacy holds significant political power and financial backing to facilitate the plan. In addition, the Papacy applied a tax to pay for the urban reorganization and new religious buildings. If there were difficulties, the Papacy claimed eminent domain to facilitate the replanning efforts. If landowners had not purchased property along major axes, at times fake facades would have been constructed to continue the consistency of the streets reading as figural voids.

Image 3: View of Via del Corso looking south from Piazza del Popolo

Though the plan is focused primarily on the eastern expansion of the city, though there are a number of axes on the western side of the city that were connecting major sites. The denser existing context allowed for shorter axes, and not as connected as the eastern sets of axes. The NOLLI MAP of 1748 shows how the axes are carved and cut through the existing mostly private (shaded) context in this select portion of the map near the northern edge of the city. The Baroque replanning of Rome was incredible successful almost 450 years ago and still clearly defines the context of the contemporary city today. These urban planning efforts influence town plans not only in Europe but also in the US, most notably for WASHINGTON D.C. downtown planning.

Media Attributions

- Baroque Replanning of Rome Plan © Edmund Bacon, Design of Cities is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Aerial View of Rome is licensed under a Public Domain license

- View from Piazza del Popolo looking South on Via del Corso © Aimee Moore is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

a tall, thin, tapered stone, constructed of one solid piece of stone (no occupiable space within the structure)