13 Acting

Acting is often considered the hardest aspect of film to write about. Given how much we identify many of our favorite films (and our most hated ones as well) with the actors who star in them, this seems counterintuitive. “It’s a Hitchcock film, starring Cary Grant,” we might say, speaking of North by Northwest. And then we will go on to describe aspects of the plot, or Hitchcock’s direction, or the look and feel of the film, but we will likely not say anything about Grant’s performance beyond fairly pat evaluations like “great” or “phoned-in.” Why is that? After all, we have very strong opinions about actors. We like our favorite actors and often go out of our way to watch a movie simply because that particular actor is starring in it. And of course, the opposite also holds true.

For example, I was utterly convinced I did not like Gwyneth Paltrow. I still am. But what is the basis of my dislike? I could point to some films in which she starred that I do not enjoy, but was my lack of enjoyment definitively due to her performance, or was it due to other aspects of the film I did not like? And what to do with the films she was in that I liked very much, such as Hard Eight (dir. Paul Thomas Anderson, 1997) and The Talented Mr. Ripley (dir. Anthony Minghella, 1999)? Her performance was central to those films, and I could not deny that it added considerably to the films in question. Maybe, in fact, I liked Paltrow just fine as an actor, but found other things about her annoying?

This gets us immediately into the ways in which film acting fades into another important aspect of performance: celebrity, or the star system. The more I reflect on it, I realize that my feelings about Paltrow as an actor are heavily shaded by my sense of Paltrow as a celebrity. We will talk about the star system more later in this chapter, but for now suffice it to say that most of my negative feelings about Paltrow like have to do with things she said and did outside her films—none of which have anything to do with her skills as an actor.

So why do I, who spends a lot of time thinking about film and enjoys reverse-engineering lighting design and camera set-ups, find it so hard to separate the actor from the celebrity? Because that is how the system is designed to work. When a producer and director select an actor for a lead role, they are thinking abut their past performances and they are thinking about all the other associations the individual actor brings to their film. Successful actors live their lives (or, more accurately, perform a portion of their lives) in the public eye to a remarkable degree, especially in countries with massively profitable film industries, such as the United States and India. Those public lives—themselves often carefully managed by agents, publicists, and other “handlers”—are often much of what we think about when we think of a movie actor. Heath Ledger’s performance as Joker in Dark Knight is, I believe, objectively excellent. But by the time I saw it on screen, my experience of it was already shaped by his sudden death during the editing of that film and the sense of uncertainty and tragedy surrounding his untimely demise

All of which is to say, when we talk about movie acting we are confronted at once by the challenges presented to us by the overlap of performance on screen and the constellation of media surrounding a celebrity off-screen. We can imagine we are able to separate the two, but we are fooling ourselves if we truly believe that. When actors are cast, their personal lives—or the versions of them we see in the media—play as big a part in the decisions as anything having to do with their performance styles.

An example: When Robert Downey Jr. was cast as Tony Stark in Iron Man (dir. John Favreau, 2008), he was still considered to be a high-risk actor following a long history of serious drug addiction, despite having been sober for several years. When director Jon Favreau told Marvel Entertainment he wanted Downey for the role, they flatly refused: he was too big a liability for a project of this scale. Favreau ultimately made his case, as he told the story later, by arguing “that the character seemed to line-up with Robert in all the good and bad ways. And the story of Iron Man was really the story of Robert’s career.”

Just because it is hard to separate the celebrity from the actor (and the more famous the actor, the harder it is) does not mean, of course, that we shouldn’t try to do so. But doing so requires that we think about what performance is, and about the unique skillset required to act in front of cameras, lights, and dozens of technicians and craftspeople on set. Here again, we run into some challenges: after all, if narrative film in the Hollywood tradition has primarily been dedicated to creating the illusion of events transpiring before our eyes, then it follows that the acting style most prized in film performers is going to be highly naturalistic, “invisible.” That is, modern screen actors on the whole are trained to act in such a way that they do not seem to be “acting”—their performances often feel effortless, authentic, “true.”

This is the other aspect of celebrity we also have to keep in mind: not only do the “private” lives of celebrities impact the way we think about the characters they play, but the characters they play also shape our beliefs about their character off-screen. When an actor primarily plays heroes, we tend to associate the actor—despite knowing better—with those admirable traits. Actors who play doctors on screen will often be asked for medical advice, and some actors (especially in long-running TV or movie series) become so associated with their roles that neither the public nor the industry can imagine them doing anything else.

The contemporary naturalistic approach to screen acting was not always the norm in narrative film, however. When film began to explore the possibilities of narrative fiction in the early 20th century, it turned, inevitably, to the example of acting that had been around for centuries: stage acting. Of course, in the early years of film, before the medium gained cultural respectability, few legitimate stage actors would participate in the upstart medium, and so what we often see early on were unsuccessful stage actors giving theatrical-style performances on screen. And since there was no sound—since these actors were deprived of dialogue—they tended to overcompensate with outsized gestures meant to communicate emotion without words.

In the earliest films this worked fine. After all, as we recall, the earliest films had a static camera and maintained a relation to the set being filmed that largely resembled that of the spectator in relation to a fixed theatrical stage. Late in her illustrious career, the famed French stage actress Sarah Bernhardt began to appear in films, most famously in Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth (1912). As the most famous theatrical actor of her age, Bernhardt’s willingness to appear in film brought to the new medium a respectability it desperately needed if it were to start attracting top actors.

However, Bernhardt’s performances also underscored how profoundly different stage acting was from screen acting. It is amazing to get to see a celebrated actor from the 19th century whose performances would otherwise be lost to us, of course. But translated from her natural milieu of the stage to the new medium of film, these performances looks stiff, stagey, rigid. Below, for example, is a clip from Bernhard’s performance as Queen Elizabeth:

Bernhardt is performing for the stage, for an audience (and a camera) at a fixed distance from her. All the action remains locked within the “proscenium arch” of the stage, the camera fixed to capture the recordings. The film, that is, is effectively a silent recording of a stage play, missing the one element for which Bernhardt was most known: her “golden voice.”

At the same time Queen Elizabeth was being filmed in 1912, in the United States, Lillian Gish was appearing in her first of many collaborations with the pioneering director D. W. Griffith in An Unseen Enemy. Together Gish and Griffith would help develop a modern grammar for both filmmaking and screen acting. Griffith would be among the first to explore the narrative and emotional power not only of cross-cutting but of alternating different kinds of shots—medium-shot, close-up—to capture different details. While Gish (only 19 when she began acting in Griffith’s films) had done some acting for the stage, she was among the first skilled actors to learn her craft performing for the camera. She developed a style that focused on toning down the broad movements and melodramatic style of the earliest stage acting on screen (desperately trying to compensate for the lack of voice and still imagining they had to be visible to the theatergoers in the top row of the balcony). Gish’s movements often still seem a bit melodramatic to our modern eyes, but she was among the first to fully explore how much screen acting depended not on the hands and body, but on the face. The ability to act with one’s face becomes crucial to the art of screen acting, as we see in this sequence from Broken Blossoms (dir. D. W. Griffith, 1919):

Here the drunken reprobate father attempts to attack his daughter, played by Gish, who has locked herself in a closet. Cross-cutting between the increasingly desperate Gish in the closet and the blows of the father’s ax on the door outside, the tension mounts throughout the scene. But it is the close-ups on Gish’s face that lend to the scene its horror and convey the character’s sense of powerlessness, with which the audience cannot help but identify.

What Gish and Griffith were exploring here in the second decade of the 20th century was the realization that screen acting actually resembled stage acting much less than had previously been recognized. In the theater, actors had to perform both for those in the front row and for those in the upper balcony, which meant a focus on vocal projection and on being emotionally legible to audience members too far away to make out facial features. Everyone watching a theatrical performance has a different perspective on the action unfolding before them. In movies, however, while some might be closer to the screen and some in the back of the theater, the camera compensates for these differences through close-up and insert shots and other details that effectively ensured that everyone always has the “best” view on the action unfolding.

There were of course other differences at the level of production. Writing in 1934, the pioneering cultural critic Walter Benjamin noted that, whereas stage acting had always involved acting for a live audience, film acting involves acting for machinery: a camera, microphones, lights. In addition, Benjamin pointed out, while the stage actor performs his part from beginning to end, the film actor’s performance “is composed of many separate performances” selected, cropped, and stitched together in the editing room:

The artistic performance of a stage actor is … presented to the public by the actor in person; that of the screen actor, however, is presented by a camera, with a twofold consequence. The camera that presents the performance of the film actor to the public need not respect the performance as an integral whole. Guided by the cameraman, the camera continually changes its position with respect to the performance. The sequence of positional views which the editor composes from the material supplied him constitutes the completed film. It comprises certain factors of movement which are in reality those of the camera, not to mention special camera angles, close-ups, etc. Hence, the performance of the actor is subjected to a series of optical tests. This is the first consequence of the fact that the actor’s performance is presented by means of a camera. Also, the film actor lacks the opportunity of the stage actor to adjust to the audience during his performance, since he does not present his performance to the audience in person. …. The audience’s identification with the actor is really an identification with the camera.

By the time sound was introduced in 1927, silent screen acting had developed remarkably quickly in learning how to perform for the camera. So it came as something of a shock when sound arrived and brought with it a sudden need to rethink many of the basic assumptions about film acting. Initially, the changes were primarily negative. Cumbersome and limited sound equipment locked the cameras down as they had not been since the earliest years of film, and actors had to learn how to perform for microphones as well as the camera for the first time. Many silent actors discovered that the skills they had focused on during the early years of their career did not translate to the sound era—as this memorable scene from Singin’ in the Rain (1952) explores in imagining the transition to sound a generation earlier:

In addition, producers realized that even when the actors could adjust to having to speak their lines for the first time, they didn’t have anything worth saying. Before the arrival of sound, screenplays were largely outlines of actions the actors were to perform. Suddenly there was a need to have proper scripts, which required the importation of skilled writers who knew how to write dialogue. Playwrights and novelists were lured to Hollywood by the studios, including Dorothy Parker, William Faulkner, and Ben Hecht. Not all of them adapted well to the Hollywood system (F. Scott Fitzgerald famously did not), but those that succeeded transformed the industry by developing the art of the modern screenplay. Now there were words worth speaking.

Along with the writers traveling from New York to Hollywood in the early 1930s, came a host of stage actors looking for work in an industry that now needed their talents. Broadway suffered severely during the early years of the Depression, with many studios shuttered and few new productions in development. Many of the actors we most associate with Hollywood’s golden age made their way West during this time, including Cary Grant, Barbara Stanwyck, Henry Fonda, Katherine Hepburn, and Humphrey Bogart. The combination of trained stage actors and sharp and witty writers led to new genres, such as the screwball comedy, which involved fast-paced verbal repartee and double-entendres designed to get past the increasingly anxious censors. Earlier we saw one example of the screwball comedy in Bringing Up Baby. Here is another fast-talking scene in a movie directed by Howard Hawks, with Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell, in His Gal Friday (dir. Howard Hawks, 1940):

In 1940, the Motion Picture Production Code of 1934 had effectively banned any frank discussion of most adult themes, including of course sex. Here Walter and Hildy have a frank and frankly ribald discussion of sex and marital discord without ever speaking any of it by name. And they do it at about 70 miles per hour. The arrival of stage actors like Grant and Russell and the writers capable of generating believable dialogue (no easy feat, as anyone who has tried to write it knows well) changed movie acting in fundamental ways. For the first time, the worlds of stage and film acting did converge in meaningful ways, even if profound differences (of the kind Benjamin describes above) continued to exist.

After all, while the introduction of sound to film brought a central element of stage acting to movies, the kinds of vocal performances necessary for screen acting remained profoundly different. Here, for example, is a production photograph from the set of Billy Wilder’s film noir, Double Indemnity (1944), in which Fred McMurry and Barbara Stanwyck’s characters meet in a supermarket to make the final plans for the murder of her husband. Note the boom microphone right over the actors heads, to catch their whispered, clandestine conversation. And of course we also see the cameras, lights, and personnel who will not be captured in the frame of the camera but of whose presence the actors are intimately aware:

Here is the scene from the final film:

This is a scene written for film actors. It would, in truth, be hard to perform on stage. Without lavalier microphones attached to the actors, which did not exist in the 1940s, it would be impossible to deliver these lines as we hear them here for a live audience in a large theater. The dialog would simply be inaudible. Similarly, if the actors were to deliver the lines with the projection they might bring to a large theater, with the boom microphone right overhead, they would swamp the microphone and produce an utterly unusable recording. Thus, many of the skills actors brought with them from the stage were now useful in screen acting, but there were major adjustments actors had to make as they moved back and forth between them (which, in truth, few actors did during this period because they were placed under rigid contracts by their studios).

Before we turn to the next stage in the development of film acting, it is worth pausing over something many of you might notice when watching classic Hollywood films of the first generation of sound in film (1927-1949). People seem to talk strangely in those films, so much so that as I kid in the 1970s I often wondered how accents and speech patterns could have changed so much in just a few decades.

The truth is that most Hollywood actors in the 1930s and 40s did not speak as they would in normal life. The mid-Atlantic or “transatlantic” accent had been associated with elite American schools and institutions in the early years of the 20th century, but it was a way of speaking—half American and half British—that was entirely cultivated (as opposed to organically developing in a particular region). It found its way first to stage and then to screen in the 1930s and dominated Hollywood voicing until the rise of method acting in the 1950s. There is some evidence to suggest it was especially sought out in the early years of sound film, as the recording technology remained fairly primitive, meaning that strong, artificial articulation was vital if speech wasn’t to be muddled in recording and exhibition. Here is an excellent example of the “transatlantic” accent in a scene between Grant and Hepburn from Philadelphia Story (dir. George Cukor, 1940):

Following World War II, the “transatlantic accent” fell out of favor and began to disappear from the screen. Rapid developments in the recording and exhibition of sound on film, especially the rise of stereo sound in the 1950s, also opened up more possibility for nuance in voice acting. In the meantime, American stage acting had been undergoing a period of revolutionary transformation, primarily due to the teachings of one man: Konstantin Stanislavski.

The influence of Stanislavski on American acting is surprising given that it occurred during the height of the Cold War, and Stanislavski was from the Soviet Union. Indeed, at a time when cultural exchange between the United States and the U.S.S.R. was almost non-existent, the enthusiasm for Stanislavski’s ideas stands out. Stanislavski was a theater practitioner and theorist who developed a complex approach to directing, staging, and acting in the early decades of the 20th century. An American tour shortly before his death, along with the publication of his theories in English-language editions, brought his methods to the U.S. in the 1940s, where they were developed into what became known as “the Method” by collaborators in New York theater, including Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, and Elia Kazan, whose students would include some of the actors who first brought Method acting to Hollywood—such as Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando, and James Dean.

So what is Method Acting? Before defining it, let’s look at two examples, in scenes from On the Waterfront (dir. Elia Kazan, 1954) and Rebel without a Cause (dir. Nicholas Ray, 1955):

In both of these scenes, we hear none of the transatlantic accents familiar to the 1930s and 40s, no artificially articulated lines. Speech is natural: it sounds like we are listening in on incredibly private and painful conversations: in one, Terry (Marlon Brando) and Edie (Eva Marie Saint) have an awkward conversation in a playground by the promenade. In the other, Jim (James Dean) has just told his family about the death of a classmate during a game of chicken at a ravine, begging them to let him do the right thing.

In both cases, our primary experience of the performances at the heart of these scenes is, for want of a better term, human. What they say and how they move is meaningful, of course, but it is the emotional naturalism—not reducible to either words or action—that is most powerful in these performances. Brando and Dean are two the most recognizable stars of the 1950s, and yet when we watch these scenes (especially in the context of the movies as a whole) we forget we are watching Brando and Dean. We believe, in effect, that we are watching real people named Terry and Jim.

The Method is based on enabling this belief, and it begins with the actor’s generating a productive belief that they are the character they play. The performance on the screen is a result of a long preparation, one that extends far beyond rehearsals. The Method actor begins with a study of the script, as a literary text and as a gateway into the life of their character. However the script is necessarily limited: the actor, after all, will only be playing select slices of the character’s life in the two hours on screen. For those two hours of performance to be convincing, the Method insists, the actor must know the whole of the character’s life. Thus, Method actors are encouraged to develop a thick backstory for their character, to imagine their childhood, their fears, their romantic predilections—details that in most cases have no direct reference or even relevance to the script. It is only by bringing the character fully to life in the imagination of the actor that they can fully inhabit them for the performance.

Of course, no amount of imagination can truly bring into being a complete lived life and three-dimensional psychology for a fictional character who exists only in parts of a 120-page screenplay. Thus the Method encourages actors to make direct connections between their own lives and psychology and that of the character they play. As Lee Strasberg demanded of his students, “What would motivate me, the actor, to behave in the way the character does?” If the character is a murderer, the actor is asked to think back to a time when they were so consumed with rage that deadly violence was conceivable. If the character is broken-hearted, they must fully bring back to life their own most devastating experiences of romantic loss and injury. And so on. As is probably clear, the Method was intimately connected, as it evolved in the United States, with a growing popular interest in psychology in the 1940s and 50s, and acting classes and preparation for a part took on many aspects of psychotherapy, asking actors to revisit and channel past traumas.

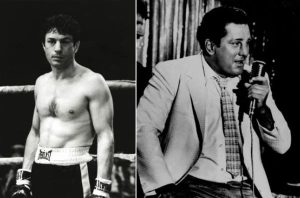

Finally, the Method highlighted the importance of inhabiting the character in preparation for the performance on stage or in front of the camera. This became perhaps the most well-known aspect of this approach to acting, as some Method actors would famously remain “in character” after the day’s filming ended. For example, Robert Dinero (who studied with both Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler) famously put on 50 pounds for his role as Jake Lamotta in Raging Bull (dir. Martin Scorsese; 1980) and worked 12 hour shifts as a cabbie in preparing for his role in Taxi Driver (dir. Martin Scorsese; 1976). Refusing makeup or bodysuits which most actors would use for roles calling for extreme starvation or for adding an unhealthy amount of weight in a short time, Christian Bale has been the human yo-yo of method actors, starving himself to 121 pounds for his role in The Machinist (dir. Brad Anderson; 2004), and eating his way up to over 220 pounds for American Hustle (dir. David O. Russell; 2013).

Such stories become part of Hollywood legend, but they also point towards the more extreme—and occasionally absurd—lengths the Method will drive some actors. It is undeniably the case that dedication to the Method can take a huge toll on actor’s physical and mental health. One of the most dedicated practitioners of the Method, Daniel Day-Lewis, retired early from filmmaking in part because of the demands of his approach to film acting. He had given himself a severe case of pneumonia (for which he attempted to refuse treatment) while filming The Gangs of New York (dir. Martin Scorsese; 2002), because staying in character as a 19th-century gangster meant he would not wear a coat in the middle of a New York winter. In preparing for his role as a frontier scout in Last of the Mohicans (dir. Michael Mann, 1992), Day-Lewis carried a 12-pound flintlock rifle with him everywhere he went, and learned how to skin animals and hunt with a tomahawk. For In the Name of the Father (dir. Jim Sheridan; 1993), in which he played a man falsely convicted by the British authorities for an IRA bombing, Day-Lewis had himself locked in prison for days without food and water—and subjected to verbal abuse and brutal interrogation by trained police interrogators.

Are all of these legends of Method actors’ extreme preparations true? Mostly, no doubt, but subject always to that blend of promotion, hype, and handling that comes with being a movie star. The Method’s extremes—and its increasing sense of both machismo and masochism—began to diminish its luster for many younger actors. Even actors like Natalie Portman, who follows many aspects of the Method in her preparation for roles, refuses the label. When it became associated, however indirectly, with the death of Heath Ledger following his intense embodiment of the Joker for Dark Knight, one sensed that the Method’s time might well have waned.

But if it is the case that fewer young actors would call themselves “Method actors” today, the influence of the method remains very much with us. After all, the primary focus of the method was in a sense only the next stage in the long continuum of screen acting away from the theatrical emphasis on movement and action, toward emotion and psychology. The dramatic change in acting styles one sees between the 1940s and 1970s has everything to do with this shift, as acting became increasingly naturalistic, human.

As early as 1932, as Benjamin notes, the film critic Rudolph Arnheim recognized that in film acting “the greatest effects are almost always obtained by ‘acting’ as little as possible.” Leaving aside all the legends of Method’s extremes, its truest impact was the creation of a style of acting that felt truly like not acting at all. Of course, a performance that looks so effortless as to be no performance at all is the result of very hard work, labor which isn’t often clearly visible on the screen (and indeed seems negated by the seeming effortlessness of the performance). I have long believed that much of the legend of Method acting derives from an anxiety that viewers will not appreciate how hard it is to inhabit a character so completely that one is not performing as him but actually embodying him. The legends of physical and mental suffering, real though they are in some measure, are also about associating hard labor with an actor who makes it look, as it were, too easy.

In truth, many actors ultimately reject the notion that one has to go through the sufferings of the Method to achieve these ends. The great Laurence Olivier, who experimented for a time with the Method, ultimately abandoned it as offering not nearly enough to compensate for its costs. In Marathon Man (dir. John Schlesinger; 1974), he played the villain opposite Dustin Hoffman’s protagonist. Hoffman was himself at the time a devoted practitioner of the Method. When Hoffman arrived on set looking deathly ill one morning, he confessed to Olivier that he hadn’t slept in 72 hours to prepare for a scene in which his character had suffered similar sleep-deprivation. “My dear boy,” Olivier exclaimed, “Why don’t you just try acting?”

At the time, it is likely Hoffman dismissed the older Olivier’s advice as coming from another era. Today’s actors would likely agree with it, even if they continue to practice many aspects of the Method in modified form. What has endured, however, is not the method but the style, and today when we see someone acting using the style of classical Hollywood or the silent era, we notice it as the exception: a studied, deliberately artificial performance designed to call attention to acting in a way today’s conventional screen performance does not. Here we might think of a director such as Wes Anderson who asks actors to deploy a somewhat flat, affectless style that makes them feel somewhat akin to marionettes. Some of the best actors of this generation have worked with Anderson (including—I’ll admit it—Gwenyth Paltrow), and so we know this performance has nothing to do with their range or abilities. Or David Mamet, whose films are based on an approach to acting he developed in collaboration with the actor William Macy—one that borrows from the Method but turns the actor not inward towards her own feelings and experiences, but outward in response to the actions and behaviors of the other characters (they call this approach “practical aesthetics”). In both cases, the style of the acting has a lot to do with the direction they receive, but also the stories these writer-directors produce. In both cases, different as they are, actors are part of a larger storyworld whose primary end is not a naturalistic realism, but something designed to be a bit askew from our world. Here are two scenes, by way of example, one from The Spanish Prisoner (dir. David Mamet, 1997) and the second from Grand Budapest Hotel (dir. Wes Anderson, 2014):

The above scenes are a reminder that the subtle, naturalistic, emotional approach to performance we see most commonly in contemporary acting is not by any means the only style of acting we see on screen. In addition to such stylized films as those of Mamet or Anderson, we should also recognize that even within films led by the most austere of Method actors, we will find other acting styles on display. For example, there are many who work long careers primarily as a character actor. Here an actor will be chosen for their association with a certain type of character—the creepy uncle, the village scold, the mad scientist, etc—and will be called on to bring that character and all its associations from one film to another, making the necessary adjustments to the script at hand.

When we see such character actors, even if we can’t remember the name of the actor without the aid of imdb.com, we immediately bring certain associations to their appearance on screen—and certain expectations. Of course this can be put to surprising effects, as when a director casts a character actor in what turns out to be a lead role or a role that plays against the expectations of their usual role. The same of course applies for all actors: casting decisions have everything to do with past work, but the goal in some cases will be to undermine the audience’s expectations, as when a character who always plays noble heroes turns out to be playing a monstrous villain.

And of course not all actors are hired for their acting. Sometimes it is a look, a visual feel that they bring to the film that is desired. Film is a visual medium, after all, and as we saw in our discussion of mise-en-scene, the movement of actors around the screen is as much a part of the visual look of a film as sets or costume design.

All actors, ultimately, are expected to have a type, a brand. And all must be able and willing to play against that brand for the good of the script. There is a lot of negotiation that goes into bringing actors into a project—actually some of the most complex and fraught in the process. Directors work with their casting director to pull together the right people for every film, but all roles have to be approved by the producer (speaking for the film production) and by the individual actors’ agents.

The agent is a newer and powerful force in filmmaking, one whose role deserves more time and attention than we have to spare. As we have discussed, during the age of the Hollywood studios’ vertical monopolies, actors had very little power and agency in their casting. They were locked down under long-term contracts, and traded between studios like property. Attempts to resist this control over their careers could be financially destructive, as it was for Bette Davis in her long struggle with Warner Bros.

All of that changed when the studios’ monopoly collapsed following the Paramount Decree. By the 1960s actors were beginning to emerge as major power brokers, along with the new figure of the independent producer. With no stable of actors to draw on, studios were now forced to negotiate with actors individually for each project, and soon agents emerged to organize the deals. A new kind of “stable” emerged, one based not in the studio but in the agency, such that a powerful agency could tell a producer that they could only have their A-list actor if they also cast two others also under contract to that agency.

The reason it worked was that stars now carried more and more power, serving as the only effective guarantee of success in an increasingly unpredictable film market. In recent decades, in fact, we have seen stars increasingly receiving producer credit, part of the deal-making from day one and lending their star power to attract investment and the participation of human capital. All of this means, of course, that casting is even harder than ever to reverse-engineer: some actors are in a role because of their past work and/or their celebrity appeal; some are there because they brought in investments; some because their agencies said so; some because of their look or “type.” And so on. Nonetheless, even as we know that we can never fully know all the planning and plotting that went into the casting of particular actors in all the roles in the film, we should think always about the why. Here are just a few of the questions we might ask to start thinking critically and constructively about the role of acting in the films we study:

- What aspects of the actor’s previous work contributed to them being cast in a particular role?

- In what way is their performance in line with previous work, and to what degree are they playing against “type”?

- Is their performance natural and realistic, or does it in some way call attention to itself as performance (melodramatic, classical, flat, etc)?

- How does the actor play off of other characters? Are there certain combinations of actors on screen that seem to generate a special energy or synergy (or conflict of performance styles)?

- If their performance is markedly different than what you have seen in another film, how might you explain that?

- When you think about a performance by an actor, in what ways are they expressing emotion or inner psychology? What parts of their body or face play an especially central role in their performance?

Media Attributions

- BTS-Double-Indemnity-supermarket

- j4pde22na4581

alternation of shots to suggest events separated in space but occurring at the same time

an actor who specializes in playing a certain "type"—sometimes an eccentric or unusual character—rather than leading roles