4 Narrative 2: Structure, Form

Last week we discussed a crucial difference that films often try to make us forget in the act of watching—the difference between the story (the “something” being told) and the film itself, the how it is told, which is never identical to the ideal of the story. We looked at some of the ways in which plot differs from story, focusing on the temporal shifts that take the platonic ideal of the story “as it happened” (whether in life or in fiction) in chronological time and transforming it into the film we see on screen. These discursive devices are what allows, as we will see later in the semester in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, seventy years of a man’s life to be narrated in two hours, or, in Bicycle Thieves, three days to be told in 90 minutes. In Rashomon the violent events of an hour in a forest clearing are retold four times through the lenses of four very different storytellers over the course of two hours on screen.

There is another crucial key to film’s ability to make us feel as if we are watching events transpire in “real time,” even as only a handful of movies in the history of cinema are actually presented in real time—that is, with a 1:1 equivalence of story-time and film-time. We discussed last week some of the ways which film elides, speeds-up, slows down, or pauses time—and on the ways it can take us in the blink of an eye into the past (flash-backs) or the future (flash-forwards). Much of this happens between scenes, in the editing techniques we will discuss in more detail in a few weeks. Within individual scenes, however, the majority do take place in what we would identify as “real”—or 1:1—time.

Let’s look at a clip from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo to illustrate this. Here, Scottie and Madeleine speak in his apartment after he has just rescued her from the waters of San Francisco Bay:

This clip (part of a somewhat longer scene) is made up of several shots. In fact, there are 12 different shots between Madeleine’s entering the room and Scottie dropping pillows for her to sit on.

These 12 shots cover less than 1 minute of the larger clip, and this pattern of cross-cutting (an editing technique we will discuss in detail later) will continue through the whole of the clip, keeping them separate until a bit later in the sequence when they will be briefly in the same shot together, signifying the next stage in their (unhealthy) relationship.

And yet, despite the large number of shots this clip, the story time represented on screen is equivalent to the screen time. The whole of the film takes place over an extended period of story-time, and yet scenes such as this (think of the conversation between Antonio and Maria about the new job in Bicycle Thieves) do occupy the same amount of screen time as the story-time being conveyed. This is not to say it is identical to the “story” because of course discourse is always shaping the story into the narrative we view on screen. In film we will find elements of this discourse in places like set-design, costumes, music, editing, lighting, and many of the other techniques and artistry we will discuss in detail in the coming weeks. But within scenes like this (and they make up the majority of individual scenes in the majority of films) story-time and screen-time are identical.

Time slips away between the scenes. Consider the clip below from Scream, which briefly hits the very end of one scene (in which our poor principal meets his end) and the beginning of the next scene in which Sidney and Tatum talk about the possibility that the wrong man might have been jailed for the murder of Sidney’s mother:

How much time exactly has passed between these two shots?

- Scene A

- Scene B

We have no clear markers letting us know whether this scene is happening later, and if so how much later. A novel will usually give us clear markers of lost time—”later that evening,” “a few hours later,” “at 5 o’clock”—to help us navigate the passage of time. Most narrative films do that kind of temporal hand-holding only very sparingly. In watching movies, we often don’t know how much time has passed, and yet we rarely find that fact disorienting or frustrating. We can pin down vague time markers here and there (“next day” signaled when it is sunny after it was dark in the previous scene, for example) and sometimes a specific time is emphasized when that time plays a crucial role in the narrative (the train carrying the bad guys into town arrives at noon). But usually time expands and contracts like an accordion and we don’t much notice—or need to. That is, until we put on our critical lenses, as we are in this class, so as to think about how and why the accordion is being played as it is.

If we pause and think about it, it is fascinating that we can register the distinction between the cuts in the clip from Vertigo as marking shifts in perspective, while we automatically comprehend the cut in the clip from Scream from one scene to another as marking a shift in time and space. After all, it is the same technique: a cut, simply two pieces of film edited together. Like so many film conventions, it has become naturalized for us as filmgoers—like reading the letters C-A-T and picturing a cat, even as we logically know that there is no inevitable connection between the animal and the letters. The result is that we both know time has passed in the second clip but we don’t register the gap as a gap. So acculturated are we to the sheer number of edits in this style of film narrative that the loss of time feels as natural as the shift of perspective in the first clip.

Other scenes, however, call explicit attention to the disruption in time. For example, in the madness scene in Vertigo time passes in ways we can’t possibly reconstruct. Is this one night? Many nights? When we see Scottie next, he is in a hospital. How did he get there? In his catatonic state, we have no idea how much time has passed, and this disorients us in ways more conventional dissolves of time do not. Here we definitely register the gap as a gap—as missing information—and this is intentional.

Time can also be be played without a visible cut, as in this scene from towards the very end of Vertigo. As the kiss begins, the camera moves around the couple, and time warps and falls away:

Here there are no visible cuts, as the set seems to rotate behind the couple as they kiss, only to dissolve back to a setting from earlier in the film: the mission stable. Scottie may be out of the hospital, but time and reality are still unstable for him (and, because the camera-narrator is privileging him, for us as well).

This brings us back to the challenge of pinpointing the source of narration in film. In a novel, the narrator is relatively easily identified. A third-person omniscient narrator who knows everything about the characters; a third-person focalized narrator, who has privilege to the inner thoughts of one character (almost always the protagonist) but who does not have similar access to others; or a first-person narrator, either the protagonist or a character-narrator (not the central protagonist but the one doing the telling, as in the case of Ishmael in Moby Dick).

The answer to the question of the narrator’s identity is usually maddeningly elusive in film, but it is still worth aexploring. Doing so reminds us that someone is telling about something that happened. As in the novel, the perspective of the narrator can be all but identical to that of the author, but it can also be different to a greater and lesser extent. We have unreliable narrators, after all (but not, we hope, unreliable authors). When I cannot identify a meaningful gap between what the film as an act of narrative is trying to tell me and what I might infer the filmmakers/author as trying to tell me, I move on, assuming any differences to be so thin as to be not worth interrogating too deeply. But when I sense that the film’s narrator’s “purpose” and the filmmakers’ purpose are not identical, that is when the interesting challenges arise.

After all, not only is the narrator of a film challenging to pin down, but the film’s author is equally so, and for different reasons specific to this medium. As we have discussed, films are the products of many hands and creative visions. We call Vertigo a “Hitchcock film” or Bicycle Thieves a “De Sica film,” but we also know that however powerful their agency was within the process, both men were only one creative agent in the collaborative authorship of the films. We might think here of “Hitchcock” or “De Sica” as a kind of personified collaborative identity, a stand-in for the collective whole of the creative process, from screenplay through to the final edits. But in doing so, we are also aware that “Hitchcock” is also not exactly identical to Alfred Hitchcock, the director, and that any sense of what “Hitchcock” wishes to convey independent of the narrator involves not one but two levels of abstraction. Unable to visualize an author as a corporate/collaborative body, we use “Hitchcock” or “Disney” as a kind of short-cut for visualizing an Author. Unable to visualize the narrator as the camera and related apparatus (the machinery through which the story is told), we fall back on a more familiar notion of the third-person omniscient narrator from the novel. Neither are quite adequate, but both will do for our purposes.

Once we have these separate conceptions of Author and Narrator in mind, we can hunt out any signs of differences between them. Think about a film like The Sixth Sense (dir. M. Knight Shyamalan, 1998). Although the ending is rarely a surprise for viewers today, when it came out it was for a time a closely guarded secret that our protagonist was in fact dead the whole time. Yes, there are “clues,” but they are clues only to be found on a second viewing, as the movie itself encourages its audience to hunt them out after the final reveal.

The impact of the revelation at the film’s end that the character through whom the narration has been focalized is in fact dead (a fact of which the character himself was unaware) is due to the revelation that our narrator was not giving us what we come to expect from much narrative film: a voyeuristic third-person view on unfolding events. Some critics recoiled against the “trick” or “gimmick” of the film’s ending as if it were a betrayal of an inviolable contract, even as such unreliability is found frequently in prose fiction (think, for example, of much of the short fiction by Edgar Allan Poe). We are surprised by this disjuncture between Narrator and Author in film because of the ways in which narrative film lulls us into forgetting that we are watching a constructed narrative at all—and thus into forgetting that there is, always, a Narrator and an Author. In The Sixth Sense we did not know our protagonist was dead because he did not know it, and our narrator was closely linked throughout with his understanding of events. The Author (Shyamalan and his collaborators) of course knew he was dead and they wanted us to be as surprised as the narrator and protagonist. That is, the goals of Author and Narrator differ and the revelation of that difference was why the “surprise” had its impact.

But even when the distance between Narrator and Author is not so extreme—as in most cases it is not—we need to remember that there is always a difference. When we think about, for example, the possible symbolic significance of the bicycle in Bicyle Thieves we are thinking about what the Author (for the sake of convenience, “De Sica”) wants us to take away. Does the bicycle symbolize class mobility? or does the quest for its return represent Faith (the brand of the bike is a Fede, which is Italian for faith)? We will look to the narration of the film to help us gather evidence, but in the end an argument one way or another will depend on our making the leap from what the narration tells us (and how) to a grasp of the intention of the Author.

All narrative, as we know from our foundational definition last chapter, is told for a purpose, a reason. We start with what the film conveys. And once we have figured that out, we can (and should) ask: does the Author want to carry away only what we have seen and experienced on screen, or is there something more, or something different that the Author wishes us to think through after the film has ended? And then of course we can ask: do we want to carry away that message? After all, just because someone tells us a story for some purpose, doesn’t mean we have to be persuaded by their purpose. But if we are to rebel against the goals of a film—to critique its purpose—we must be confident we have identified that purpose.

All of this comes with an additional turn of the screw in narrative film, as the medium often links us as viewers to to the perspective (POV) of the protagonist. This is why an unreliable narrator in film can be jarring in ways different than we experience it in a novel. After all, we have “seen it with our own eyes,” in a photographic medium, and we are trained to believe in the objectivity of vision even as we know better (even as the magic of film depends on the fallibility of our vision). Therefore, just as we look for potential gaps between Narrator and Author, so too must be be vigilant for gaps—often invisible on first viewing—between the protagonist whose perspective is privileged (or focalized, to use a term coined by the narrative theorist, Gérard Genette) and the narrator. Each of the arrows represent places to poke at for gaps:

protagonist POV –> Narrator (“camera”) –> Author (often referenced as the director; ex., “Hitchcock”)

Sometimes the difference between these various stages in the process of presenting a narrative in film will be so small as to be not worth examining in detail. But where we find a gap, we should dig in deep and work against the grain of film’s ability to link us to the protagonist and/or to make us take what we see on the screen as story (events happening before our eyes) and not as narrative (something told for some purpose by somebody). It is there many of our greatest insights will arise, as the films that move us take on new layers of meaning and complexity.

The majority of films in the narrative tradition popularized by Hollywood (and adopted in various ways in cinema traditions around the world) can productively be described in terms of a three-act structure. Anyone in our class who has ever taken a screenwriting class immediately can visualize this structure, even if its conventionality makes an ambitious young screenwriter resistant to its dictates. It is so ubiquitous that screenwriters are forever trying to break free of it, yet it stays with us—and even many films that claim to abandon it are still bound by its structures. Of course, some of the great films—especially outside the U.S. tradition—do not follow this structure, and so it is far from universal. Nonetheless, it is a great place to start not only for aspiring screenwriters, but also for students of narrative film.

The basic shape of a three-act structure goes something like this:

Act I is what I think of as “Normal”: it is here we are introduced to the main character(s) and their version of everyday, for better or worse. Often the kind of “normal” our central characters occupy in Act 1 is determined by genre convention. For example, in a romantic comedy, “normal” will always be unhappy: our main characters are bored, or they are risk-averse, or they are unhappily attached, or they are lonely, etc. We don’t find, for example, many romantic comedies in which our protagonists are happy and in commited relationships when they first meet each other and launch the movie into act 2. The breakup of a happy normal is not the “meet cute” the genre leads us to expect.

Normal will often look quite different in other genres. If it is a horror movie, the “normal” in which we first encounter our protagonist is often pleasant: their life is safe, hopeful, and our protagonist is blissfully unaware of the monster that is fast approaching. In a western, the “normal” of Act 1 might show us the retired gunslinger, now happily engaged to the mayor’s daughter and looking forward to a quiet life managing a store in town. And so on. The important thing is that Act 1 is all about establishing a baseline “normal”—one to which at film’s end we expect/hope the protagonist will return (if “normal” is happy) or from which we hope they will be liberated (if “normal” was unhappy).

I often come back to romantic comedies when describing the three-act structure, and only in part because it is one of my favorite genres. One early classic of the genre is the film Bringing up Baby (dir. Howard Hawks; 1938), starring Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn. Grant plays a nerdy paleontologist, obsessively working on assembling a Brontosaurus skeleton. He is almost finished, missing only one bone: the “intercostal clavicle.” He is engaged to a sour young woman and their wedding is fast approaching but he is too obsessed with his project to even notice how joyless will be the future to which he is committing. The future does not look bright, but he seems to have no imagination that life could be any different. This is Act 1.

And then, while playing golf in the hopes of securing an investment in his museum, the first inciting encounter occurs. It does not at first seem very romantic:

Surely there can be no happy shared future for this serious, risk-averse paleontologist and the whirlwind that is Hepburn’s Susan Vance. Except we know it is a romantic comedy, and so of course this unlikely couple will, in the third act, find true love. But it will be a circuitous route, a long way that makes up the whole of Act 2 and the majority of the film.

In the classic Hollywood tradition, Act 1 is quite short, sometimes no more than 10 minutes. The goal is to let us know the protagonist and their baseline “normal.” Once that normal is interrupted—in this case by the collision with Susan Vance, who will carry Grant’s paleontologist along on a wild ride—Act 2 is under way. And this act makes up the majority of the on-screen time of a conventional Hollywood film.

Acts 1 and 3 are conventionally brief compared to Act 2. This is true with many Hollywood narrative films, especially those working within the conventions of genre. “Normal” is not where the narrative interest lies, and once resolution has happened (the couple is married, the monster is dead) narrative interest drains quickly once again. Because of this, however, some argue that three acts is insufficient to capture the “beats” of a script, and thus even our chart above breaks down Act 2 into rising action, climax, and the movement towards resolution.

I continue to turn to three-act structure when I attempt to reverse engineer a screenplay or think about the larger structure of a film narrative because it is informative to find out how well—or poorly—the film fits the expectations of the three acts. When it does not, it tells me something about the ambitions of the screenwriter and filmmakers. When it does, I know to look at how the transitions between acts is navigated.

Keep in mind that the “normal” of Act 1 is often not going to be our normal. If it is a science fiction film, it almost certainly won’t be. The “normal” we are being acclimated to here is the normal of the protagonist, or—if the film has no clear single protagonist—of the storyworld. Act 2 begins when that normal is shattered in some way by an inciting incident. What shifts the story from Act 1 to 2 is when the rules of normal are shattered—as when the alien is loose on the ship or, in Bringing Up Baby, when our paleontologist finds himself carried out of his boring comfort-zone off into adventures that include, among other things, encounters with criminals and chasing after a leopard.

If the shift from Act 1 to 2 is usually pretty clearly marked (the monster arrives, the unlikely couple collides), the shift from Act 2 to 3 is sometimes only fully clear in retrospect after the credits roll. In Scream we can identify the shift when the true identities of the killers are revealed and Sidney exacts her bloody vengeance. Within the third act there is often a twist in some genres, as when the monster seemingly comes back from the dead to attack one last time, forcing the protagonist—the lone survivor—to draw on unimaginable reserves to defeat it once and for all. And this brings us to resolution, a return to a “normal”: the end (in Scream, this return of “normal” is signified by the dawn, and with it, the promise that the town will be safe once again).

What the return to normal looks like at the end of Act 3 will vary greatly, often dictated by genre conventions. In a horror movie, normal means the defeat of the monster, but the monster’s terrors throughout Act 2 have so changed the survivor(s) that normal will never be the same as what it was in Act 1. In a romantic comedy, we always begin with a protagonist in a place we understand to be less than ideal, so we don’t want them to return to the old normal. Instead we are rooting for them to discover a new normal by partnering with the unlikely individual who represents everything that is antithetical to their previous life. In some films, where the normal of Act 1 is understood to be desirable, the disruptions of Act 2 can be safely exiled, allowing the protagonist to return to their lives before the disruptions. Here I am thinking about the western, in which the retired gunslinger is forced to defeat the evil bad guy from his past before he can safely return to his girl and his longed-for quiet life. In all cases, however, the force that unraveled the normal of Act 1 must be resolved so that the film some normal—old, revised, or new—can be (re)established.

It probably goes without saying, but of course the resolution of Act 3 is often not going to be what we as viewers desire for our protagonist. Think about Bicycle Thieves. We can identify Act 1 as the normal in which we find Antonio and his fellow army of unemployed men and women, and the everyday horrible choices the family must make between, for example, bedsheets and bicycle. The inciting incident that fully takes us into Act 2 occurs later than in many Hollywood films, but it is nonetheless recognizable: the theft of the bike, which transforms in an instant the story of Antonio and his new job into an impossible quest for the return of the promise of a new beginning.

If Act 2 comes later than it would in a conventional Hollywood screenplay, Act 3 comes very late indeed—with the decision to steal a stranger’s bike. The film ends just a few minutes after this fateful decision, as father and son walk, hand in hand, into the crowd towards home. There is no clear resolution. None of what Antonio (and the audience) had hoped for has come to pass: no job, no return of the bike, no promise of a better future for Bruno. We anticipate along with Antonio the disappointment on the part of Maria when she learns that the bike has not been recovered. We wonder if father or son will tell her about the thwarted theft Antonio perpetrated. We wonder what the future holds for the family. Here we see how a three act structure doesn’t necessarily promise a return to “normal” that is desirable. In this case, in fact, it is fair to say that the “normal” to which both Bruno and Antonio return at the film’s end is bleaker than the one with which they began.

This model of three-act structure can rightly be challenged as overly simple, and many screenwriters argue for other ways of mapping out the narrative beats of a script. But in general, such models are only adding more detail to the basic structure described above, and three-act structure is a good place to start for thinking about the structure of many narrative films, even as we recognize that there are many for which it will not apply. That said, while this approach to thinking about narrative structure works well for thinking about a lot of narrative film, it does not work cleanly for all. For example, the three-act structure will prove a more challenging fit for a film like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (this week’s film) and even more so for a film like Zone of Interest, which we will discuss later in the semester. Nonetheless, there is value to seeing if the structure might fit if only so we can begin to see the alternative structure with which it is working.

In fact, there is a strong tradition of narrative film—internationally and in the U.S.—that actively resists many of the patterns central to the three-act structure we have just described. A narrative film in the Hollywood tradition can use this 3-act structure because it follows certain features in its approach to narrative that are well adapted to it. For example, a commercial narrative film in the Hollywood tradition relies on a protagonist, one about whom the viewer is quickly educated in terms of their defining characteristics and their central problem, a problem which the long struggle of act 2 will ultimately resolve in the descending action of act 3. In film that actively positions itself as an alternative to this tradition—including many international art house and independent films—we cannot necessarily count on the central consistent character, single-mindedly dedicated to resolving a central problem. Nor can we count on resolution itself. For example, the ending of 400 Blows (dir. François Truffaut; 1959) refuses the kind of ending—happy or sad—we have been trained by other films to expect. Instead we end in a state of uncertainty as to the future of our protagonist, an uncertainty manifested on screen by the freeze-frame with which the film ends:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bO8XIm6bbgA

This refusal of the three-act structure’s promise of resolution does not, of course, mean the film has no structure. But it forces us out of the familiar patterns of genre and convention to attend to the structures of the film at hand. However, because of the dominance of the Hollywood tradition of narrative film, it is fair to say that much cinema in the world is thinking about these conventions, even if only to reject them, to position themselves against them. Thus it can be helpful to compare an art film or independent film to those structures to see how it consciously refuses the expectations (as in the refusal of closure in the end of 400 Blows). After all, three-act structure depends on certain conventions that define what is sometimes called “mainstream film.” Here are a few of those narrative conventions or expectations and the ways in which many art films resist them:

| “Mainstream” film | “Art” film |

| Clearly identified protagonists | Central focus of the film’s attention can change |

| Psychologically consistent characters | Characters capable of manifesting dramatic shifts in motivation and behavior |

| Clearly defined “normal” that is disrupted | “Normal” is often either not clearly defined or is not under threat or pressure |

| Characters have clearly defined goals | Characters often lose sight of original goal, or have no clearly defined goal |

| Clearly defined endpoint (the protagonist’s goal is achieved or fails) | Endpoint not clearly defined; ending can feel arbitrary |

| cause-and-effect plot structure | episodic plot structure, where one event follows another often randomly |

| omniscient “neutral” narration | often subjective narration |

| inconspicuous style to preserve the sense of events happening | filmmakers’ style often foregrounded |

As we can see, the first five items above have consequences on how a story will be structured. The decision to make narrative film primarily about the goal-seeking, consistently-defined protagonist leads, almost inevitably, to the three-act structure. Adelaide is who Adelaide is within the first minutes of Us, and we would be confused and even betrayed if she suddenly late in Act 2 became a practical joker or a naive goof. Hollywood storytelling has trained us to expect to get all the clues we need to identify the main traits of our main character within the opening minutes of the film (by the end of Act 1 at the latest).

One more example: The opening minutes of Game Night (2018) tell us almost everything we need to know about our two protagonists: they are hyper-competitive, obsessed with games (and with winning them), and a source of frustration to the friends who depend on them for their social life:

Before the title of the film has even appeared on the screen, we know they will be forced to make small but crucial changes in relation to their negative traits (hyper-competitiveness) even as their positive skills (working together to find winning strategies at games) will be rewarded in the conflicts of Act 2. They will “improve,” yes, but they will not radically transform into something unrecognizable to the characters we meet in the opening minutes. The pursuit of a goal sparked by the incident that disrupts the “normal” of Act 1 will develop certain aspects of their character and perhaps purge certain negative traits as they develop. But there will be no radical change. Batman, the obsessive, grim superhero-detective we meet in Act 1 will not in Act 3 suddenly blossom into a flamboyant performance artist.

Such transformations can happen in “art films” that actively position themselves against mainstream Hollywood narrative traditions. A character might change so much as to be unrecognizable to the character we first met. While this sounds absurd, given our expectations as veterans of mainstream cinema, it is arguably less absurd than the expectation that characters remain psychologically consistent. After all, humans are bundles of complex personality traits, sometimes scaring our friends with mood swings or a sudden change of priorities or goals. The “art film” seeks to capture this aspect of humanity that so much mainstream cinema smooths over.

The items listed in scarlet in the chart above are consequences of the earlier priorities around character and the stories we tell about them. Here we a shading away from structure and into questions of style and, more broadly, form. We will talk about style next week and in the weeks to come (as we look at how style is produced on screen). But it is worth pausing over the idea of form here, because it allows us to see structure as one organizing pattern among others.

The form of a film includes narrative structure. It also includes a wide range of other elements we will be looking at in the weeks to come. Form is the system of relationships between all the elements we see on screen, of which the structuring of events in the screenplay—our main focus here—is only one. Film is a multimedia narrative form; we gain information not only from the actions the characters perform and the words they speak, but also from the movement of the camera, the lighting, the editing, etc.

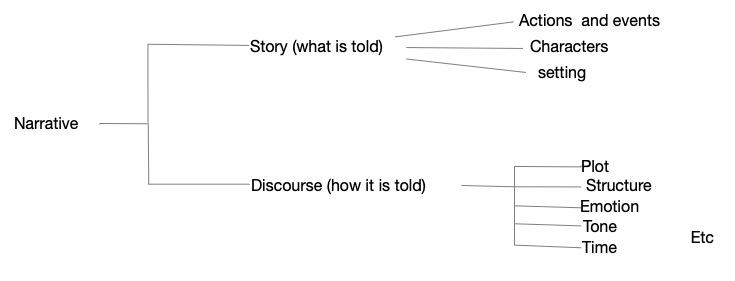

Returning to our imagined scene of oral storytelling from the previous chapter, in which you are telling your roommates about something that happened to you that day, we will surely think about structure—the order of the story, what you highlight and what you leave out. But other elements shape how your story will be received: tone of voice, hand gestures, facial expression, expressed emotion, etc. This gets us closer to thinking about all the elements of film discourse. Of course, in film, we also have sound, photographic images, and other elements we cannot reproduce through oral storytelling. Last week we focused on what discourse does to story in the telling, highlighting the difference between the narrative we are told (plot) vs the whole of the story implied by the telling (story) that we reconstruct in our mind. Story structure is a way of describing the shape of the plot, seeing the relationship between its component parts. Other elements such as emotion, tone, and focalization (who is seeing?) contribute towards a fuller understanding of the part of the definition of narrative we did not address fully last week: “for some reason.” Why is the story told? What impact does the film wish to have on us? How can we understand that “reason” and how might we judge its effectiveness in meeting those goals? Here we will look at structure, but also at the other elements at play in filmic storytelling we will discuss starting next week (design, cinematography, editing, sound, etc). and their relationships to each other. Those relationships, the larger patterns that emerge, is a film’s form. Form includes structure, but it also describes all the other relationships and patterns (including emotional and stylistic patterns) that contribute to the shape of the film discourse and the narrative we see on screen.

Last week we focused on what discourse does to story in the telling, highlighting the difference between the narrative we are told (plot) vs the whole of the story implied by the telling (story) that we reconstruct in our mind. Story structure is a way of describing the shape of the plot, seeing the relationship between its component parts. Other elements such as emotion, tone, and focalization (who is seeing?) contribute towards a fuller understanding of the part of the definition of narrative we did not address fully last week: “for some reason.” Why is the story told? What impact does the film wish to have on us? How can we understand that “reason” and how might we judge its effectiveness in meeting those goals? Here we will look at structure, but also at the other elements at play in filmic storytelling we will discuss starting next week (design, cinematography, editing, sound, etc). and their relationships to each other. Those relationships, the larger patterns that emerge, is a film’s form. Form includes structure, but it also describes all the other relationships and patterns (including emotional and stylistic patterns) that contribute to the shape of the film discourse and the narrative we see on screen.

Because a film’s form involves so many elements and so many overlapping patterns, it can be hard to talk about with precision. I recommend starting first with structure as a way of understanding the patterns with which most films begin. The screenwriter sits at her keyboard giving shape to the story that will one day be on screen, reshaped in its final version by numerous hands (from lighting designers to actors to editors). Almost all films begin as text on page, with a screenwriter thinking about narrative structure. While what appears on screen will be something more complex than that original script, as it is translated from a textual medium into a multi-media medium (film), that original structure remains in place beneath all the layers that grow around it during the production process. Think of the narrative structure as the skeleton. We can’t see it from the outside, but its scaffolding holds everything else in place, and we can intuit its shape by how the body of the film moves through space.

The form of the film is like the body: containing a skeleton that gives it a rough shape, but also defined in infinitely unique ways by the relationship between countless other features (the color of the eyes, the texture of the hair, the way the body moves across space). In the weeks ahead we will be diving deeper into that anatomy, pulling the skin off the body of the film to see how all the parts hang together around the screenwriter’s original skeleton. (Don’t worry, we will safely put the film back together again after so others may enjoy it). We are in effect training to be anatomists of film, and even if we can never describe all the manifold relationships that make up a film (any more than we could with an individual person) we will learn how to identify the crucial ones for each film we study. Starting with the skeleton of narrative structure, we will come to understand how films are made to come to life.

Playing with Film

- Take a “mainstream” film you have seen recently and describe how it works in terms of three act structure: what is the “normal” established in act 1, how is it disrupted in act 2, how does the tension rise throughout act 2 and what is the incident that shifts it into act 3 and the movement towards resolution. Are there aspects of the film you are describing that seem to not fit into this structure?

- Can you think of a film that you have seen that feels hard to fit into the three-act structure—where there is no clear inciting incident to lead into act 2, or no clear shift to act 3. Tell us about it, and where it fits and where it resists a 3 act model

- Do you like diagrams to visualize complex and/or abstract concepts?

- Take a pass at mapping out some of the concepts discussed in the first half of the chapter and last chapter—Story, Discourse, Author, Narrator, Focalized POV, etc.

- How would you map out the relationship in Scream or Bicycle Thieves between the POV of individual characters, the filmic Narrator, and (if you think there is any space or difference between it and the Narrator) the Author?

- This week’s film is a bit dizzying the first time through in terms of how much the implied chronology of the story is transformed by discourse into what we see on screen. How might you map the chronology of the major events in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind as they took place in “real” time against the chronology of how we see the events ordered on the screen?

- Take a stab at trying to figure out how much time passes between some of episodes in Bicycle Thieves, those cuts in which time has clearly passed when we shift to the next shot.

Media Attributions

- intro-1647447042

- Film-strip-clipart-frame-clipartfest

- Set-up-1

- 3

a SHOT or series of shots depicting a single, continuous action and which takes place within one specific place or setting.

a single continuous piece of film, however long or short, without cuts or optical transitions.

alternation of shots to suggest events separated in space but occurring at the same time