9 Cinematography II

Last week we considered the work of the cinematographer in terms of composition, aspect ratio, types of shot in terms of the relationship of figure to frame, and angles of shot in relationship to what is being photographed. This week we turn to some of the other many other choices and considerations the cinematographer faces when preparing to film a scene, including camera movement, focus, and speed.

A lot of what we discussed last week are considerations that are as much a part of the workings of still photography as they are of cinematography. When I worked as an assistant for a commercial photographer in my younger years, we talked a lot about composition, about lighting, about aspect ratios (in traditional photography we called these formats), and about types of shots in terms of figure-to-frame and in terms of the camera’s angle on the subject. While cinematography is of course related closely to still photography, it is the addition of the <em>kinema—</em>the movement—that we turn to now in considering the movement of the camera in the act of filming bodies and landscapes, themselves in motion.

As you will recall from our first week together, the earliest films had little to no camera movement: the camera was extremely heavy and it needed to be anchored in place to prevent it from creating unpleasant vibrations in the final image. But as with lighting, innovation and technology moved quickly to meet a newly emerging need for movement. One of the first important movements we saw evolve way back in one of our earliest films was the pan. Here was one of the examples of this movement we looked at in our first full week together, from The Lost Child (1904):

As we discussed at the time, the pan here, in which the fixed camera pivots to the left to follow the anxious mother as she pursues the imagined kidnapper of her baby, likely emerged as a solution to the problem of how to stage action over a larger space than earlier films had attempted. Once the mother leaves the yard, there is a desire to be there for the action that can be partially satisfied by this simple (yet unprecedented) camera movement. Of course, the frustration we felt in watching the whole of the scene above, as the action disappeared around behind the house and we were left anchored in place until the next cut, will require a new kind of camera movement we will turn to shortly.

Quickly, the pan became a part of the fundamental grammar of cinema. Because the camera is fixed in space as it turns—right or left—to follow an action or to study something otherwise off-screen, it imitates the experience of the viewer, herself fixed in place watching the movie. In this early scene from Rashomon we see the Priest, himself fixed in place, turning to watch the Husband and Wife after encountering them on the road:

Here the camera is linked with the subjective perspective of the Priest as he watches the Husband and Wife pass. We see a similar shot below in the anthology film The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (dir. Coen Brothers, 2018), in which the character played by James Franco is cornered after an aborted bank robbery. (There is an extended “pan shot” gag at the end of the scene, although it is unrelated to the camera movement we are discussing here). Here we pan from Franco to his horse he is hoping to summon to him and then back to Franco: pan left and then pan right:

However, a pan need not be linked to the point of view of a character, and in fact the vast majority of pans function in a way that call attention to the independence of the camera-narrator in the film’s narrating. Here, for example, is an animated GIF compiling a few of the many pans in The Grand Budapest Hotel (dir. Wes Anderson; 2014), edited together. I have added arrows to spell out the obvious: a pan is simply a fixed camera turning its gaze left or right.

From this simple movement, the desire for more movement naturally follows. The close cousin of the pan (indeed, closer to a sibling, in that they both involve a fixed camera) is the tilt. Here instead of moving left or right, the camera moves up or down, as in this rather surreal example from Inception (dir. Christopher Nolan, 2010):

Tilts can be used in combination with a low-angle or high-angle shot, as discussed in the previous chapter, with exciting impact, as in this scene from early in The Matrix, in which Neo is ordered by an unknown caller to take a leap of faith, even as the high-angle shot coupled with the quick tilt down reveals how unprepared he is at this stage in his journey:

Before we move on to camera movements in which the whole camera, and not just the head of the camera, is in motion, it is worth pointing out that we sometimes combine adjectives with these two movements to describe the relative speed or slowness of the movement. For example, we might describe the camera as “slowly panning left,” thereby describing a leisurely movement of the camera’s eye across a space, conveying, perhaps, a lack of urgency on the part of the narrator. For a particularly fast pan—one so fast we can hardly make out the intermediate visual information even as we can tell there is no cut employed—we use the term swish pan (or whip pan). Such movements are most often used as transitions between scenes, but they can be used to other effects as well. (This can occur with a tilt, as well, although they are more rare). Below is a sequence from towards the end of Some Like it Hot (dir. Billy Wilder; 1959), in which we cut between our two protagonists (one with Marilyn Monroe and the other in drag and being courted by a devoted admirer), with the swish pan providing the transition:

A swish- or whip-pan can also be used in action movies, or to create surprise, or to link together two dramatically different spaces. This short video does a nice job explaining some of the possibilities from the combination of the right-left camera movement of a basic pan with the element of extreme speed:

Which brings us back to 1904, and the poor cinematographer who so wished he could follow the mother in The Lost Child as she ran away after the imagined kidnapper. In fact, even as that film was being made, early experiments were taking place with moving the whole of the camera. You might recall the very early example we looked at in week one of what comes to be known as a dolly shot. In Photographing a Female Crook (1904), we saw the camera move towards the “female crook” in question. Since the camera at this point would have been too heavy to carry with any stability, we can presume the camera here was placed on a platform on wheels—a dolly:

This ability to bring the camera in towards the subject was arrived at in this 1904 film as a way of revealing the visual gag of the suspect’s comical expressions. This is one of the very first uses of the shot we know of, but like the pan it was soon showing up everywhere; it was not long before the equipment used to transport the camera became more sophisticated—most commonly a small wheeled vehicle affixed to a track that could be laid down according to the needs of the particular shot. Here are two images of directors testing out dolly shots before filming, roughly a half century apart:

- Ida Lupino

- Michael Bay

Because filmmakers quickly discovered that a more stable moving shot resulted from placing the platform on which the camera was to move on tracks, the term dolly shot can for the most part be used interchangeably with tracking shot. Some definitions insist that dolly shot refers to shots made with a platform with wheels and no tracks, while tracking shot should be reserved for shots made with tracks only. This distinction might well be useful from a production standpoint, but for us as students of film, there is often little to no way we can tell from a given shot whether the movement of the camera through space is aided by wheels or tracks. For that reason, I tend to use them with some degree of equivalence, although I prefer to use the tracking shot to describe a dolly shot in which a particular character or other moving object is being kept pace with—or tracked. As we will see below, there is a more significant difference between the dolly or tracking shot and the zoom shot that we should fret over instead of that between dolly and zoom. But my distinction allows me to think about what is motivating the moving camera: is it following an object or a character, or is it heading off on its own to look at something we hadn’t attended to previously?

Here is a famous shot from Weekend (dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1968):

Although we frequently lose sight of them in the chaos, we are following, or tracking, the couple in the black convertible, and even as we lose them for a bit we eventually pick them up again and then pan right to follow them away from the scene. I would use the term tracking shot here, not just because tracks were used in the film (they were, a lot of them), but because we are following our protagonists (at least for the first part of this strange film) as we move down the tracks. On the other hand, I see the following example as a dolly shot. From Citizen Kane, here we dolly in on Mr. Bernstein towards the beginning of his story. The main subject is not moving, and we are instead moving closer to him (on tracks or wheels; the distinction is hardly relevant to us as viewers).

Indeed, many film writers use tracking to describe the horizontal movement of the camera across the screen plane, and dolly to describe a scene in which the camera moves closer or further from the subject. That is also fine, as far as I am concerned, although it leaves somewhat uncertain the question of what to do with a moving shot which is not tracking anything in particular. The great Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni often allowed his tracking shots to continue after his characters left the scene or to go off in seemingly unmotivated directions, as in the example below from L’Avventura (1960). Because we want to be able to describe movements like this, we might need to draw on other terms, such as “unmotivated” or “disconnected” to qualify it.

Ultimately, using the two interchangeably is fine, so long as we draw on additional adjectives and descriptive language to make clear what we are seeing and how we understand it being used. After all, none of what we are discussing in terms of camera movements (or, for that matter, types of shots, as discussed in the previous chapter) is used in isolation. To briefly use the analogy of music, what we are describing here is akin to notes in a composition, which gain their meanings and impact from combinations over time. Thus in the scene above from Citizen Kane we see an eye-line or neutral shot dollying in from a long shot to a medium close-up. These terms allow us to describe with some precision what we see on the screen.

Few of the shots we think of as the greatest in film history are just one note. When I look back on my list of favorite shots, all of them have multiple elements, different “notes”: sometimes played at the same time, sometimes in sequence—or, to draw one last time on the music metaphor, sometimes as chords, sometimes arpeggiated. This, to my eyes (not my ears, which are brought into play when we turn to sound in two weeks) is the visual music of cinema.

Here is a scene from early in Get Out (dir. Jordan Peele; 2017) in which the character played by LaKeith Stanfield is stalked and finally abducted in a wealthy neighborhood, with commentary:

Of course, the movement of the camera itself (right/left, up/down, forward/backwards, etc) is only one of the way in which we can create movement on screen. Alongside the dolly or tracking shot, we must consider the kind of movement that can be created without moving the camera at all, through the use of a zoom lens. In fact this variable focal length lens brings up a whole new range of choices for a cinematographer when planning for a scene: what lenses to select and how to use them in the shooting of a particular scene.

The zoom lens first made its way into film in the late 20s, but it was used relatively infrequently until late in the studio era. What we call a zoom shot is often classified as a “camera movement” but in fact the camera moves not at all. Instead a zoom lens has variable focal lengths and by adjusting the lens, the camera operator can create the sense of being closer to or further from the subject.

The important distinction between a zoom and a dolly or tracking shot is that in a zoom, the camera remains in place and only the lens is “moving.” Here is a beautiful example from Barry Lyndon (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1975), in which the camera zooms out:

The actor does not move in relation to his setting. But neither does the camera. What happens in a zoom shot is that the focal range changes and the lens pulls back, widening its field of view and creating in-camera the kind of movement that had earlier only been possible by moving a camera physically through space, closer to or further away from the subject. But the differences between the two are not simply mechanical. A tracking shot moving toward a subject is physically changing the relationship between camera and the subject being photographed. On the other hand, a zoom shot is not moving at all, only changing the level of magnification. The easiest way to attune ourselves to the difference between the two is to keep in mind the following distinction:

- In a zoom shot, as the subject gets bigger (or smaller) within the frame, the spacial relationship between the subject and the objects or people around the subject will not change.

- In a tracking or dolly shot, the relative position of everything within the frame changes constantly.

Sticking with director Stanley Kubrick, we can perhaps see this difference more clearly by comparing examples of his zoom shots with his tracking shots. First, here are two examples of zoom shots in Kubrick films, one a zoom in (The Shining [1980]), and the other a zoom out (Clockwork Orange [1972]).

By comparison, we can look at this shot (also directed by Kubrick) from 2001: a Space Odyssey (1968), in which we can see our relative viewing position change as we get closer to the subject being photographed:

If the distinction is still feeling unclear, do not fret: it vexes even veteran film viewers. It will get easier, I promise. And this short video will help drill down on some of the crucial things to keep an eye out for:

Perhaps not surprisingly, many cinematographers combine the effect of the dolly with the impact of the zoom for what is called a zoom dolly (or dolly zoom) shot—although it can feel very different based on whether the camera is moving in or out and whether the lens is zooming in or out. Probably the most famous and influential version of the zoom-dolly is found in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), where his cinematographer, Robert Burks, figured out a way to reproduce on screen the subjective experience of our protagonist’s severe pathological fear of heights as he climbs the stairs of a mission bell tower:

While there are earlier versions of this technique, this one was so influential that it became known as the “vertigo shot,” produced when you dolly while zooming in the opposite direction. In the clip above it allows us to experience a sense of the debilitating condition that has grounded the career of our protagonist, a former San Francisco cop, and which is here being used against him as part of a complex conspiracy.

A similar zoom-dolly shot can have a very different narrative function, however, as in this shot from Jaws (dir. Stephen Spieglberg, 1975), in which our protagonist suddenly realizes that all his fears were right: his community is indeed under attack from a massive shark:

Thus a similar technique (dolly in one direction and zoom in the opposite direction, at the same time) can serve very different function in a film depending on other contexts and narrative elements. In Vertigo the technique disorients us as our protagonist is disoriented, whereas in Jaws it focuses us as our protagonist is being called to face the reality of the horror that is upon his town. In both cases, however, it is clear that this technique is especially well-suited to creating a sense for the viewer of subjectively seeing as the subject on the screen sees or feels.

The variable focal-length lens allows other techniques, including one of my favorites: the rack focus. Here the shift in focal length changes dramatically what is in and what is out of focus on the screen. In this way, without a cut, we can shift our focus from one character or object to another. Here is an example from The Host (dir. Bong Joon-ho, 2013), in which our protagonist’s attempt to make an escape from a hospital is spoiled by a pursuer who suddenly comes into focus behind him.

It can be used to great effect in horror movies, as in Devil’s Backbone (dir. del Toro, 2001) when our protagonist is hiding from his pursuer and the focus shifts such that we suddenly realize how close the pursuer is. But it can also be used, as in the scene below from Young Victoria (dir. Jean-Marc Vallée, 2009), to create moving fields of focus in an otherwise visually overwhelming scene:

Once we combine framing choices with camera movement and variable focus, new possibilities emerge for not only composing in depth but narrating in depth using different focal lengths. In this scene above, we learn who is looking at whom (and who is worth looking at) by the racking focus of the camera as it moves about the grand dining room.[1]

As the lenses grew faster in their ability to adjust focus, not surprisingly we also see a variation of the zoom shot rise in popularity, one closely related to the whip pan discussed above: the snap zoom or whip zoom, in which the lens zooms in at breakneck pace towards the subject. This has been a technique particularly beloved by some directors, including Quentin Tarantino and Edgar Wright. Here, for example, we see its repeated use early in Shaun of the Dead (dir. Edgar Wright, 2004):

This discussion of the kinds of “camera movements”—zoom, rack focus—which are in fact more accurately described as lens movements—leads us to a discussion of lenses themselves. There is so much involved in the selection of lenses by a cinematographer and their crew, much more than we can capture here. In truth, as film viewers, we mostly need a a few broad distinctions in categories of lenses, focusing on those whose impact is clearly visible on the screen.

Effectively, we can divide lenses into two broad categories: zoom and prime. A zoom lens, as discussed, has variable focal lengths, whereas a prime lens has only one focal length. The question might reasonably be asked: why, if choosing between a lens which could adjust its focal length and one which is fixed, would one ever choose the latter? I am happy to get into the technical weeds separately if folks want to talk lenses in more detail, but the short answer is that prime lenses offer three crucial advantages over zoom lenses: they are sharper (because built to manage only one focal length instead of many across a scale), smaller (for the same reason), and they are faster.

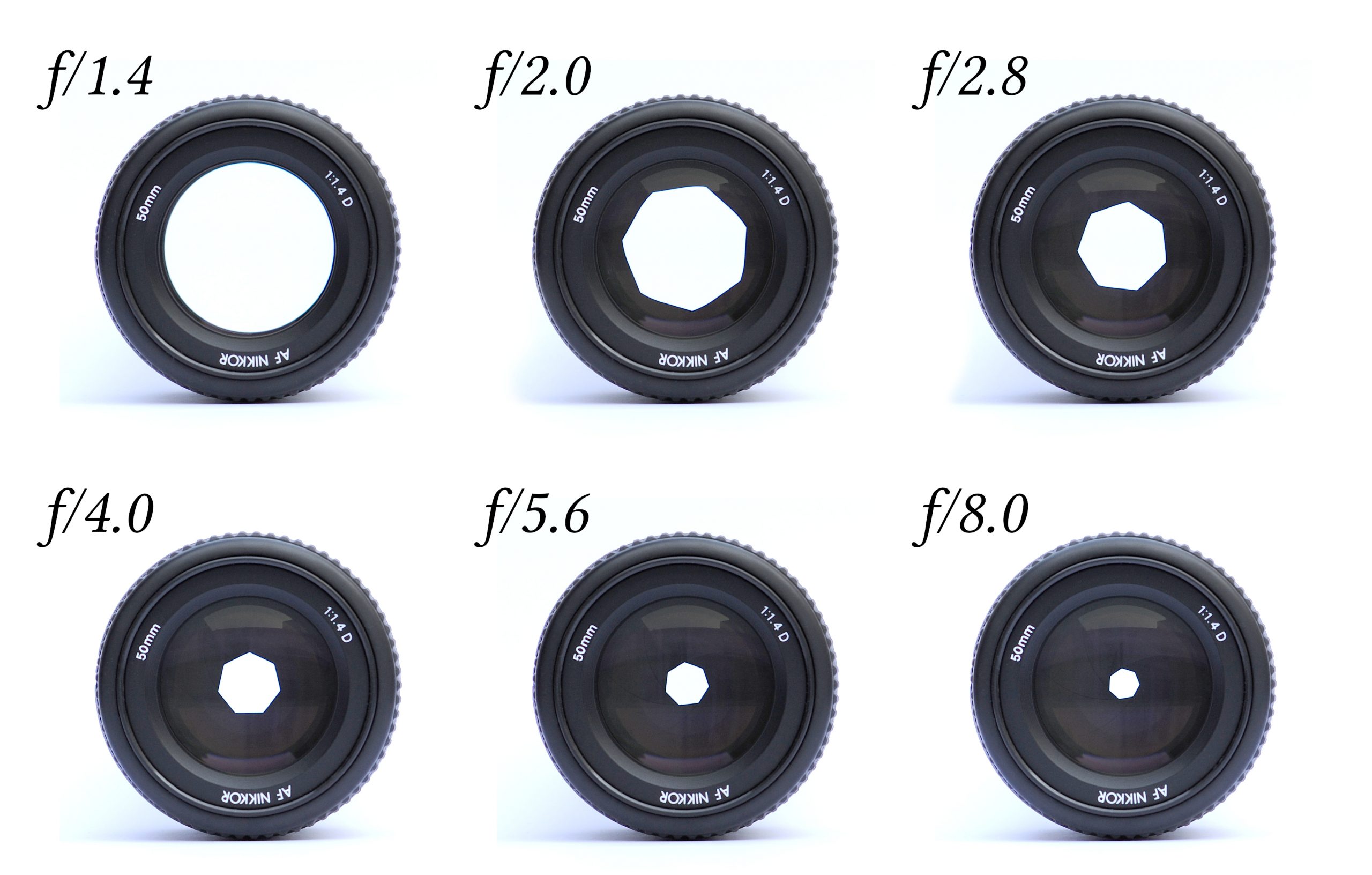

It is the last one that is especially crucial for many setups, so let’s pause over this technicality and consider what the “speed” of a lens means. What we are discussing refers to the maximum aperture diameter, or minimum f-number, of a lens. A lens with a larger maximum aperture (which is signaled, confusingly, by a smaller minimum f-number) is called a “fast lens” because it can achieve the same exposure with a faster shutter speed. All of that can be a bit dizzying if you are new to photography, but it helps us understand why a cinematographer will choose a prime or fixed lens over a zoom lens.

Few zoom lenses have apertures wider than f/2.8 (in fact, most cinematographers will stick with a zoom lens aperture around f/8.0 because sharpness diminishes with anything wides in these lenses). If a larger maximum aperture means more light is reaching the film (or the digital sensor, in the case of contemporary digital cinematography), then a zoom lens will not be well suited for low-light scenarios. In such scenarios one would want as wide an aperture—or as “fast” a lens—as possible, as can only be achieved with a prime lens.

Prime lenses offer other possibilities for a cinematographer beyond simply achieving good results in low-light situations. When a cinematographer selects their lenses for a given film, they are often looking for lenses that have certain effects. The cinematographer for Moonlight selected lenses he knew produced high-contrast images. Once you have the lens whose look you like, then, the cinematographer selects a set of primes that will do the full range of what might be needed for various planned shots.

In the set above, the lenses on the lower row (18mm-32mm) are what are called wide-angle lenses. If we think of 50mm as roughly equivalent to the visual field of the human eye, anything wider (again, counter-intuitively, with smaller mm) will feel wide in what it is capturing. Technically, any lens with a focal length shorter than the length of the sensor or film (measured diagonally) is wide-angle. But for our purposes, we are only interested in the effect on screen. On the lower end of the scale, the effect of the wide angle starts to warp the image, such that it feels like looking through a fish bowl. Such extreme wide-angle shots are called “fish-eye”:

This scene from A Clockwork Orange (dir. Kubrick, 1972) is filmed with a wide-angle lens a bit less “fishy” than the one above. But as the character moves through the record shop, one can see the warping of the space on the sides of the frame. Here the effect is to capture the character’s warped narcissism, as he sees himself very much at the center of the universe, with everything bending around his gravitational pull.

A 50mm lens (on a 35mm camera or digital equivalent) is generally understood to be a standard lens: that is, its range of vision and depth of field aligns with what we experience as “natural” vision. Here is a 50mm lens being used to shoot a scene from Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960):

Anything larger than 60mm is a long-focus lens, in which the set focal length is significantly longer than the length of the sensor or film, as measured diagonally. Here the effect is easily recognized on screen, especially when the lens is very long. In the scene below from The Graduate (dir. Mike Nichols, 1967), our protagonist is racing to the church to try and stop a wedding. Because the telephoto collapses the distance between foreground and background, it feels like he is making no progress as he runs towards the camera, ramping up the tension of his race against the clock:

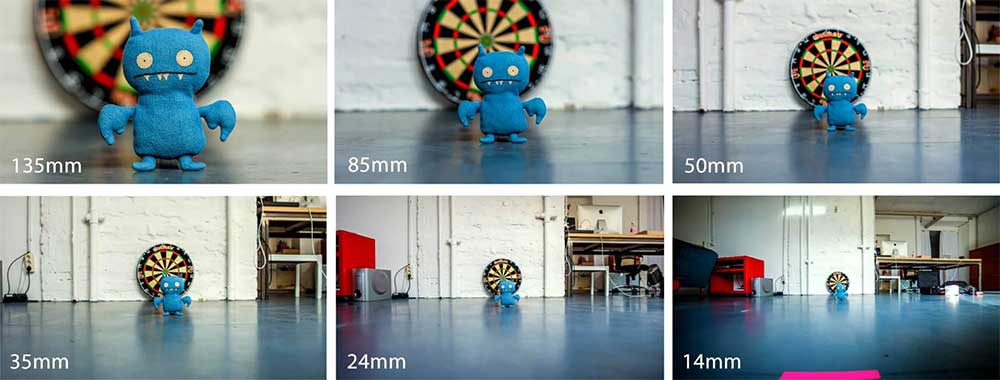

In the images below (borrowed from a useful website that goes into more detail on this subject) we see two ways of thinking about the difference different focal lengths make when choosing lenses. In the first set of images, the camera is not repositioned, and we see the changes that happen simply by switching out lenses of various lengths. In the second image, the camera is repositioned so that the figure (our little blue guy) remains framed similarly in each shot, with the changes in lenses impacting what is in frame and in focus.

There is a lot of technical stuff here, I know. We are not expected to be able to identify what focal length is being used. But we should keep an eye out so as to be able to indentify the broad categories of wide-angle, standard, and long (or telephoto) lenses and the unique shots they produce. As you watch for them, and you will start to see them more easily—faster than you might expect.

Speaking of “fast”… a brief conclusion to the chapter on the question of speed as it applies to film and cameras (both still and moving image). Above we discussed the idea of a “fast” or “slow” lens, referring in that instance to how wide the aperture of the lens opened and thus how quickly light made its way to the film or sensor. Making life terribly confusing for film and photography folks is the fact that the language of “speed” (fast and slow) is used in other ways as well.

For example, one of the things a cinematographer and her team needs to think about is shutter speed. The shutter is a plate located between the lens and the film stock (or CCD chip or other sensor in digital photography). This plate has an opening that blocks and admits light at variable speeds according to the camera settings. The shutter speed is measured in fractions of second: 1/50 (0.02 second) is the standard shutter speed for film cameras.

Shutter speed determines how long each frame of a film is exposed to light, which, like the f-stop, affects the image’s overall exposure. The more a frame is exposed to light (when slow shutter speed is used) the brighter the image will be because light hits the film or sensor for a longer period of time. Conversely, the less a frame is exposed to light (when fast shutter speed is used) the darker the image will look.

Shutter speed and lens speed are obviously linked, but maddeningly there is a third element of “speed” to account for: the speed of the film stock itself. This is a measure of a given photographic film’s sensitivity to light, measured most commonly on the ISO system. A slow film stock has a lower ISO, meaning it requires more exposure to light, whereas a “fast” film has a high ISO. A faster film will work better in low-light situations, but it will also produce a “grainier” image, as we can see in the scale below. A slower film will produce a “tighter” image—sharper and more detailed— but will also require more light to achieve.

In fact, these three variables of relative speed—lens, shutter, and film speed—together serve to create a formula by which some of the most important decisions the cinematographer’s department will make are calculated. Although far beyond our orbit on the other side of the camera, when making films ourselves, we always are balancing film speed, shutter speed, and lens speed in combination. Any change to one of the three will impact the other three if the correct exposure (the amount of light necessary for the reproduction of the image) is to be maintained. This is often referred to as the “exposure triangle”:

We don’t have to worry about the technical details or any formulas here, but it is worth keeping in mind that cinematographers will sometimes select a fast film not because of its suitability to low-light condition but for the grain it generates on screen (where, as in the example above at the highest ISO, everything starts to look like an impressionist painting).

Of course, the question of film speed depends on, well… film. Shutter speed and lens speed translate to the digital age, but not so film speed because in the digital age there is no actual film. And this leads to a nice transition into next week’s discussion of editing and post-production, as in digital filmmaking many of the effects we associate with the choice of a faster or slower film stock are now created post-production, much in the same way we would apply filters to our Instagram photos designed to capture the effect of slow film where no actual film exists.

Media Attributions

- 16970925ab473b004de1025cf483c928

- Lenses_with_different_apertures

- copset10

- Fisheye-Lens-The-Favourite

- understanding-focal-length-Same-Distance.jpg

- understanding-focal-length-different-distance.jpg

- iso-compare-zoomed

- triangle

- This would have been a challenging sequence to plan, as the rack focus requires both a camera operator and a focus puller working in sync ↵

a camera movement in which the camera pivots left to right or right to left on a horizontal plane from a fixed point.

a camera movement in which the camera moves up or down from a fixed pivot point

an extremely fast pan movement, often used at the end of a shot as a transition to the next shot.

a camera movement in which the entire camera moves on a horizontal plane in space

a camera movement in which the apparent distance from the object changes from far to near or near to far (not through camera movement but through changing the lens magnification).