11 Sound I

As we know, the first generation of cinema was silent, the technology for combining sound and image not becoming viable until 1927. Yet, it is an exaggeration to say film was ever truly silent. Historians of silent film remind us how cacophonous the silent movie theaters were. Sometimes the sound was deliberately added, as in the case of a narrator, or a piano, or (at the prestige picture palaces) a small orchestra. Sometimes enterprising owners of the early movie theaters provided sound effects behind the screen. But always there was the voice of the audience, commenting on the happenings on screen, flirting or gossiping, and just generally engaged in the social experience of early film-going. So in truth film was never truly silent, and certainly movie theaters were more boisterous places than they are in our modern times when we are commanded to sit silently and not comment on what is happening on screen.

Nonetheless, it is the case that we can have a film with no sound at all, and it will still be a film. As discussed at the start of our work together, sound is not fundamental to the definition of the medium. We cannot, for example, have a film that contains no images, and only sound—that would be an audiobook or a podcast, not a movie. Because sound came later to the party, sound has often been under-valued in film studies, often treated as supplementary or as an add-on to the experience of watching movies. Since no feature narrative film has been made in many decades, however, that has been entirely silent, I think we can agree that not attending to film sound is a serious mistake[1]

When we discuss film sound, we are actually describing two very different things: diegetic and non-diegetic sound. Diegetic sound includes everything that is represented as being sourced in the storyworld: dialogue, the sound of footsteps, a car’s tires squealing as the bank robbers make their escape, etc. Diegesis derives from a Greek word meaning simply “narration, narrative,” and we use diegetic it here to reference anything that is part of the represented storyworld. This does not have to be something we see on screen. The sound of the screeching car wheels from the bank robbers’ getaway car might well be happening outside the bank while the camera remains inside with the frightened patrons who have just been held up at gunpoint. But even if we never see the car, the sound makes sense to us as part of the narrative and we understand it as diegetic.

At the same time, however, we are likely listening to non-diegetic sounds as well. In film, the primary non-diegetic sound we hear is usually from the soundtrack—score or song—playing as the action unfolds. Since I’ve been using a bank robbery as an example, let’s look at the first couple of minutes of this heist scene from The Dark Knight in order to distinguish diegetic from non-diegetic sound:

The first sounds were hear as the clip begins is already a mix of both: we hear the angry shout of the Joker’s henchman (“stay on the ground!”) and the sound of his blow to the security guard. These are both diegetic: they are linked to people and actions we can see on screen so we are confident they are part of the storyworld. However, even as these diegetic sounds are occurring, we also hear the pulsing rhythms of the soundtrack rising in volume and eventually moving into the foreground of the auditory track as the scene continues. This is non-diegetic sound, not sourced to anything in the storyworld but clearly belonging to the world on the other side of the camera—the abstract entity that serves a narrator’s role in the telling of the story.

Here we might return profitably to our distinction from earlier from Chapter 3 between the narrator and the story he tells:

| Diegetic Sound | Non-diegetic Sound |

|---|---|

|

|

Of course, in many scenes, as in the robber scene above, diegetic and non-diegetic sounds are mixed together. Unlike visual elements, which can be easily separated and categorized, sound blends and mixes so that we have to actively work to pulls the two types of sound apart. But in fact we are always doing so, whether we are attending to it or not.

Let’s look at another bank robbery, this time from a clip from the beginning of Baby Driver (dir. Edgar Wright, 2017) to think about what we might gain by more consciously attending to the distinction between diegetic and non-diegetic sound:

As we watch our robbers leave the getaway car, heading towards the bank they are about to rob, we hear only the song “Bellbottoms” (1994) by the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion. Despite the fact that we see our protagonist (who we don’t yet know is our protagonist) put headphones in his ear and turn on an iPod, in 2021 many of you might not even recognize the almost antiquated digital music device. And even if we did, we would likely not associate it with certainty with the music that dominates the scene. Not, that is, until our protagonist begins to move in time with the music behind the wheel of the car. At that moment it is clear that the music we might have assumed was associated with the soundtrack—that is, non-diegetic—was in fact emanating from the storyworld (diegetic).

Of course, this distinction then raises other questions. After all, only our protagonist can hear the music on his headphones—which continues throughout the heist and the frenetic car chase to follow. So can it be said to be emanating from the storyworld in the same way that it would be if, for example, he were playing the music on the car stereo? Not exactly. Yes, it is diegetic (it has to be, since the character hears it), but it is also subjective: we are hearing what only one of the characters hears. In this way, it is closer to what we would usually call internal-diegetic sound, a term we usually use for interior monologues we are allowed to hear even as they are represented as going on in the character’s mind.

Making matters more intriguing (and confusing) is the fact that everything seems to be choreographed in sync with the song. The heist begins with the opening chords of the song and ends with the fading chorus of “bellbottoms, bellbottoms…” at its end. As the action heats up inside the bank, the music’s tempo increases. Indeed, everything we see on screen seems perfectly in-sync with what we hear, as we would usually expect in music composed for a movie (a score, or a song commissioned for the soundtrack).

Thus, while we can categorize the sound as diegetic in that a character in the film is obviously hearing it (even if the others are not), it also tells us something about our protagonist and his idiosyncratic relation to music and the world (and of course driving). We know we are seeing the world through his eyes, focalizing the bank robbery such that it falls into rhythm with the music. We know we are living in a world, in short, in which real life has a soundtrack and thus is not entirely “real” for him—making him a potentially unreliable narrator indeed.

Some films enjoy playing with the distinction and our expectation even more than does Baby Driver. For example, Something About Mary (dir. Peter and Bobby Farrelly; 1998) has a repeated structure where Jonathan Richman plays the role of a kind of singing narrator, beginning with the title sequence:

The sound era began in 1927, with the premier of The Jazz Singer (dir. Alan Crosland, 1927). For the first time, an entire feature length film was shown with recorded sound and some dialogue from beginning to end. In truth, the film has relatively little dialogue, but it does have a recorded score throughout. Part of the reason for this is that synchronizing the voices of the actors with the image on screen remained a very shaky proposition until the early 1930s. In this earliest sound film, the sound was recorded on a record, which had to be perfectly synchronized with the film in order for voice and image to appear as if they were connected to the same body. Here is an example of one of the longer sound sequences in the film, before the “no!” of the father interrupts the reunion of mother and son and returns the film back to silence:

The transition to sound of course required a massive investment to convert theaters for the new technology. Fortunately for Hollywood, this was some twenty years before the Supreme Court forced them to surrender their theater chains, and so they still owned all the theaters and were free to make the investment themselves. Nonetheless, it was a massive commitment to take all the theaters in the country and add speakers and other sound equipment. However, from the very beginning, all the studios understood there was no going back once sound became a possibility.

The first sound films were projected into the movie theater on one speaker, usually residing behind the screen. This is monaural or mono sound: all sound information is conveyed via one track, usually pointing toward the audience. As a kid in the late 60s, almost all recorded sound in my life was monaural: my TV, my transistor radio, and my little record player had only one speaker. But by the 1970s, when I went to the movies, things sounded very different indeed.

This is because by that time most movie theaters had converted convert to stereo sound. Stereo sound seeks to reproduce the effect of our binaural (meaning simply that we have two ears) biology by splitting sound into a “left” and a “right” track. Movie theaters began to convert to stereo setups in the 1950s, following early experiments over the course of the previous decade, beginning with Disney’s Fantasia (1940). By the time I was a regular movie-goer in the mid-70s if I stumbled into an old mono theater is sounded weird and unnatural.

The switch from mono to stereo is the beginning of the shift towards ever more immersive sound, and beginning in the late 1970s the technology would accelerate at a surprising rate. In the 1970s, movie sound moved from stereo to a new system developed by Dolby, which utilized three channels instead of two (left, right and rear). This effectively began to subdivide the two channels of the stereo setup with three speakers in the front and two in the rear to carry “off-screen” sound. Of course, having this new theater technology meant we needed sound designers on the post-production end who could mix the sound for these possibilities (at first very unevenly distributed at theaters across the country).

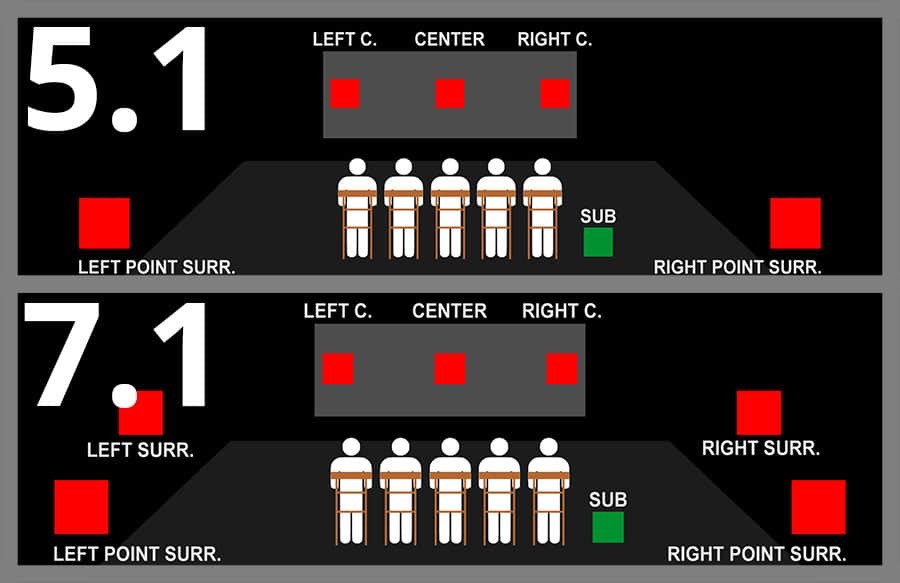

In the late 1980s, we see the emergence of the new 5.1 standard, in which sound is now divided into 6 different channels in post-production so the sound, during exhibition, can be funneled to speakers in the center (primarily for dialogue), left and right (stereo), and rear left and right. This is the 5 of 5.1, with the “.1” being the addition of the subwoofer, a speaker (or speakers) designed to carry the lowest undertones.

To this day, the 5.1 speaker remains the basis not only of many movie theater speaker set-ups, but, increasingly in the 21st century, of many home theater setups as well (we will talk about the impact of widescreen TVs, DVD, and the “home theater” later in the semester). If there are any audiophiles in the class, you know that 7.1 has become increasingly the gold standard in both theater and home audio setups, and today every film is mixed in 7.1 even if this more advanced set-up is mostly available only in first-run theaters. The 7.1 adds two additional channels to the 5.1—a right and left side surround speaker:

Thus we see that, in less than a century, we have gone from sound projected in movie theaters from a single source, to sound increasingly being distributed around the viewer, enveloping them in a way that the visual track (bound by the limits of the frame and our eyes) cannot. Of course, none of these channels, whether simple stereo (2) or 7.1 (8), will produce anything but monaural sound unless the sound track is mixed and coded to distribute discrete channels to the proper speakers during exhibition. That is, just adding speakers by itself won’t make the sound “surround”: to do that requires sound mixing on the post-production end, a system for encoding that mix on the soundtrack of the film (analog or digital), and equipment on the other end that can interpret that code on the soundtrack and distribute the sound information encoded there around the various speakers. The goal of all this increasingly enveloping sound design is to give to the soundtrack depth and dimension, so that it mimics the way sound information comes to us in real life: sound connected to the things we see in front of us through a central channels, sound from events happening in the distance mixed down to exist “behind” foreground sounds, sounds emanating from sources off-screen coming out of speakers that roughly correlate with the source location of that sound in relation to the action on the screen.

The reason for all this investment of technology and innovation in movie sound is clear: it takes what stubbornly remains a framed two-dimensional image that only fools us into accepting it as three-dimensional, and sutures it to a soundtrack that is, in fact, truly multi-dimensional. The effect is that our ears send information to our brain in relation to the visual track that can (when done well) elevate the experience of verisimilitude and “immersiveness.” It is not surprising that the rise of these multi-track sound systems went hand-in-glove with the rise of the blockbuster era, beginning with films like Star Wars (1977), which was mixed in a unique 4.2 system. Batman Returns (1992) was the first film to use Dolby Digital 5.1 on 35mm prints, whereas the first film released in 7.1 was Toy Story 3 (2010). Each of these big budget films is also a film that is based on making a fantasy—space cowboys, superheroes, toys who talk— believable to audiences. While all of them involved important innovations in the visual track, their success depended on the sound track pushing into ever more immersive space surrounding the viewer to augment the illusion.

In this way, sound becomes something that must be not simply recorded and engineered for the soundtrack, but actively designed, both in production and post-production. In the early sound era, the sound department was likely to include only a couple of credited individuals (for example, Public Enemy [1931] credits two people in the sound unit). Twenty years later, the situation had changed little (Sunset Blvd. [1950] lists only two crew members responsible for sound).[2] As recording technologies improved and as first stereo and then Dolby exhibition possibilities emerged, sound began to suddenly take on much more importance. By the 1970s, a new title had emerged in movie production: the sound designer. Just as the Production Designer was responsible for all elements of the pre-production look of the film, the Sound Designer emerged as the individual responsible for the overall sound of the film.

The first individual to be credited as a sound designer was Walter Murch, in 1969. A longtime collaborator with Francis Ford Coppola, Murch introduced into cinema a radically new approach to recording and mixing sound that began to work to shape the sound—but also to use sound to give shape and depth to the two-dimensional image on screen. Starting his career in a pre-digtal world of analog recording and editing equipment, Murch ended up transforming the understanding of what sound could do in and for a film, and many of his principles would make their way over into the digital era to follow. This short video below explains in detail the concept of “worldizing” Murch developed in the 1970s:

In the 1970s and 1980s, the sound designer grew in prominence and a new set of principles began to define the role of recording and mixing sound for film:

- Sound as integral to all phases of film production

- Sound as potentially as expressive as image

- Together image and sound say more than either could alone

- Image and Sound are not always saying the same thing

These principles are seen at work in this opening scene from Apocalypse Now (1979), in which Murch worked as Sound Designer:

As the film opens from black and silence, the first sound we hear off screen is a strange, ghostly sound which eventually is matched to a source as a helicopter enters the screen from the left. No other diegetic noises are heard during this opening, even as the bombs begin to fall on the Vietnamese jungle. The diegetic sound of the helicopter, however, soon (sonically) dissolves into the sound of the ceiling fan above our prone protagonist, in his Saigon hotel.

Of course, the helicopter is not the only sound we hear. Just as the helicopter makes its first pass across the screen, the opening notes of “The End” (1967) by the Doors begins to play. This music is of course non-diegetic, and yet combined with the diegetic sounds of the helicopter something new emerges that is not reducible to either helicopter (diegetic) or song (non-diegetic). And of course soon the image changes as well, first as the incendiary bombs hit the jungle canopy, setting the landscape on fire, and then as we start to see visual overlays of our protagonist in his room, remembering the scenes of horror we ourselves are seeing on the screen—and clearly continuing to relive the horror even in his relative safety in Saigon.

All of the principles of sound design are at work here, as image and sound (and sound and sound) combine to communicate more than either could alone, and as the complex mix of the sounds of the helicopter/ceiling fan against the music of the Doors gives us an insight into the state of mind of our protagonist that no words could as economically or effectively convey. And we also see/hear here how image and sound can say different things, forcing us to combine the two to make sense of what we are seeing and hearing (a helicopter? a fan? the sound of a man’s mind breaking?).

It is worth noting that the helicopter sound was produced on a synthesizer and then mixed and shaped in complicated ways around the channels that constituted the sound track. It is important to note that just because a sound is not recorded from the object that we are told is producing it doesn’t mean the sound is not diegetic. Indeed many of the sounds we hear as being “produced” by various objects and people in film are in fact added or enhanced later, as we will discuss more next week. For more on how the sound for this scene was produced, check out this fascinating video, which describes the ways in which Murch and his recording engineers planned and produced the movement of the sound:

As you can see from the video above, sound is not the straightforward process it once was (and which many still imagine it still to be). Anyone who has shot a video with a decent camera and a terrible microphone knows how much bad sound can destroy our experience of an image, no matter how beautifully filmed. And as in all things in filmmaking, the more we understand the power of sound, the bigger the sound team becomes, with specialists ready to contribute at every stage of the film production process.

Indeed, that it probably the most important change in sound design today compared to before the 1970s. Where previously the sound team joined the film for production, recording the dialogue and other sounds from the sets before heading into post-production to add additional sounds to the final mix, today the Sound Designer plays a role at every stage of the process.

- Pre-production: planning the design

- Production: recording on set

- Post-Production: editing & mixing

This brief video about the sound design in Argo (dir. Ben Affleck, 2012) describes the ways in which planning for the design of the sound in the film was central to the film’s preproduction work from the start. It also shows some of the ways in which Sound Designer Erik Aadahl captured various key sounds—street protest, sirens moving through the streets, etc:

Argo was nominated for Academy Awards for both Sound Editing (Erik Aadahl, and Ethan Van der Ryn) and Sound Mixing (John Reitz, Gregg Rudloff, and Jose Antonio Garcia). These two awards often cause confusion on Oscar night, and indeed they all work together on the same sound team. But the work is fundamentally different:

Sound Editing is the art of building and shaping individual sound tracks to accompany the visual track

Sound Mixing is the mixing of the individual sound elements (including music) into a unified whole

This distinction usefully points out how sound editing is primarily focused on diegetic sound, while it is the job of the sound mixing team to bring all the parts of the sound track—diegetic and non-diegetic—into the kind of unified whole we experience at the beginning of Apocalypse Now.

The definition of sound mixing team therefore reminds us of the other crucial team, aside from the Sound Design team, vital to the sound of a film: the Music Department. After all, Argo also received a nomination for Original Score for the composer Alexandre Desplat. The music department works independently of the sound department until the final mix is being produced. Music is often a late member to the film production party, although the composer is hired early on to start developing themes for the film as a whole and, in a traditional film score, for individual characters and moods. But of course, the final recording cannot be produced until the film is cut: how else to time the transitions, the beats, and synchronize the music with events transpiring on screen?

One of my friends was a film composer in Hollywood until very recently, when he returned to theater where he had gotten his start as composer of Hedwig and the Angry Inch. He served as composer for over twenty feature films during his career, including big box office films like Little Fockers and small independent films such as Station Agent. But in all cases, the work was largely the same: after being hired and meeting with the director to discuss their vision of the music, he received a script and a budget to work with, from which he would hire the musicians needed to bring his score to life. He would get cuts of the film in production as he worked on the score, getting to know the characters and the space through which they moved. He came of age as a movie composer in the digital age, so he would load the footage into his computer and compose various themes and motifs to the film. Once a rough cut of the film was complete, he could begin finalizing his score and plan recording to be mixed in with the final cut. The sound mixer would be on hand for this stage so they could be planning the final audio mix to be sutured to the final visual cut. Aside from a few cosmetic fixes or adjustments, this is often the final stage in the making of a feature film, composer and sound mixer effectively the last two creative agents applying the finishing touches.

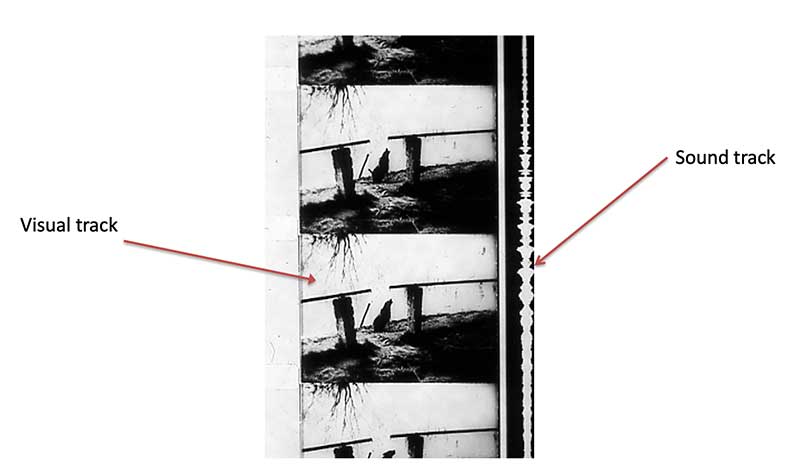

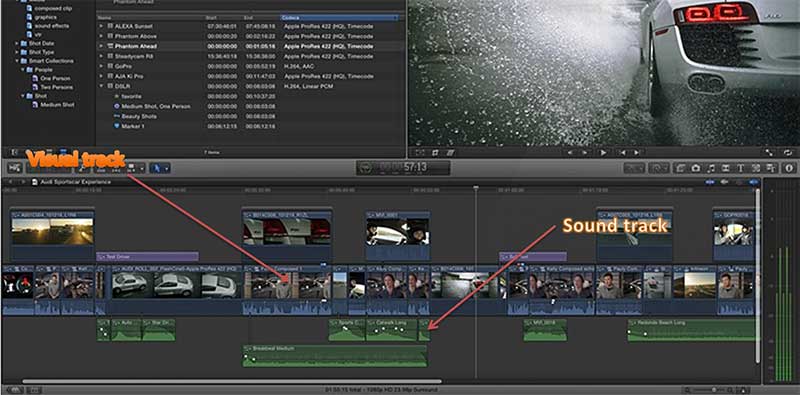

- traditional film

- digital film editing workstation

We will return to sound next week, focusing on it in relation to editing. For now, let us summarize some propositions to keep in mind when thinking about sound in film:

Sound helps define:

- Space

- Mood

- Audience expectation

- Audience identification with characters

- Connections between scene

- Character point of view

- Emphasis

- Rhythm

- Themes

While sounds of course “mix” in the film’s sound track, we can nonetheless analyze and categorize them. The first categorization is whether or not they are diegetic or non-diegetic. If diegetic, however, we can drill down further and think about whether the sound occurs off-screen or on-screen, and whether it is external (produced by an agent within the storyworld and heard by those present) or internal (for example, the inner thoughts of a character, not audible to others in the storyworld but “overheard” by us).

With editing we will also introduce the question of whether sound is simultaneous or synchronous with the visual image which it is source or is asynchronous or non-simultaneous. We will think about the ways in which film can serve as a bridge between scenes, and the ways it can be layered to call our attention to something that is only barely visible on the screen. Sound, it turns out, plays a rich and powerful role in film after all.

Media Attributions

- psycho

- Untitled

- 5.1-vs.-7.1-Surround-Sound-Featured-Image-Smaller

- There have been films in recent decades that have no spoken dialogue or diegetic sound, but even these homages to the silent era have recorded sound tracks. Examples include Margarette's Feast (dir. Renato Falcão, 2002) and The Artist (dir. Michel Hazanavicius, 2011) ↵

- More than these two credited individuals most certainly worked on the sound, of course. In the studio era, the studios housed a sound department that managed the technicalities of getting the sound ready for the final film. But this work was largely uncredited because it was wrongly not thought at the time to be creative or essential. ↵

Sound which is represented as originating in the storyworld of the film

sound which is represented as emanating from sources outside the story world of the film

sound coming from the mind of a character (an interior monologue, for example) that we can hear but the other characters cannot