1 The Origin of Film and the Beginnings of a Film Grammar

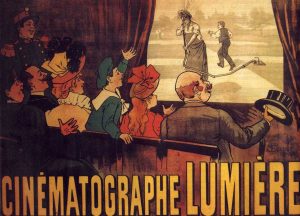

The first time a film was projected to a paying audience was in Paris, at an exhibition of the pioneering work of Auguste and Louis Lumière in December 1895. The concept of moving pictures was by no means new to those gathered, however. Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope, a device that displayed moving pictures through a peephole, was already widely popular.

|

|

Which of these was the origins of film? If film depends on a crowd and on projection onto a screen, the case could be made for the Lumiére brothers and their cinématographe exhibition. If it depends only on the illusion of motion created by a mechanical device, then surely the kinetoscope wins the prize, right?

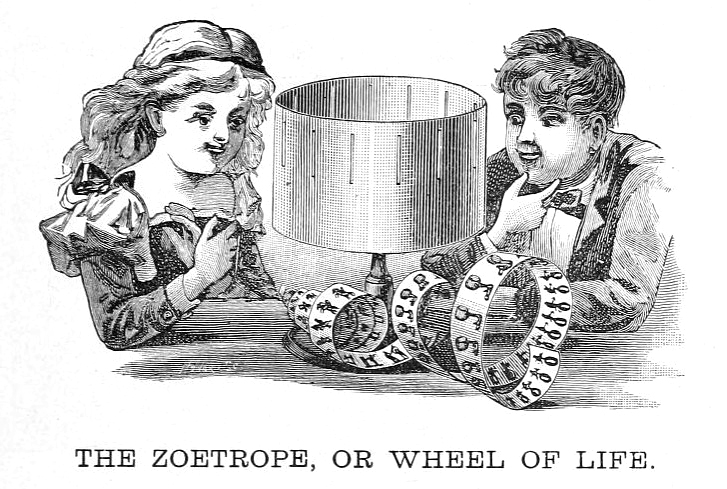

As always in the search for “firsts” and “origins,” the answer is messy. In the case of film, all the more so, in that devices creating the illusion of motion from static images were in fact already long-familiar by the 1890s. Perhaps the most ubiquitous such device throughout much of the second half of the 19th century was the zoetrope, so popular it was patented and marketed as a toy by Milton Bradley in 1866. The zoetrope used sequential drawings capturing movements to create an illusion of seamless animation when the wheel was spun and the viewer focused through the slits in the wheel.

Is this, then, the origin for film? After all, the technology works much like later celluloid film: sequential strips of still images, each breaking down a movement into small gradations, set in motion at a sufficient speed to create an illusion of the still images moving. Or what about the Émile Reynaud’s innovations with the praxinoscope (a successor to the zoetrope), which allowed him to take much longer strips and even project them onto a screen?

Most film historians understand these earlier nineteenth-century technologies—from the thaumatrope to the praxinoscope—to be examples of precursors to film, or “proto-cinematic” devices, instead identifying the experiments that emerged out of photography as the “true” precursor of film as we know it. This gets us at something that has until fairly recently remained crucial to most definitions of film: the role of the photographic (as opposed to the drawn) image. As we will discuss late in the course, this distinction has begun to break down in interesting ways in the 21st century, and it was most certainly not a meaningful distinction in the late nineteenth century either. Instead, it was imposed retroactively by early 20th-century critics, historians, and professionals eager to define the field in which they were seeking to claim a place. The illusion of motion created from sequential images that are drawn, it was decided, is animation, while the same technique using sequential photographic images is film.

Like many definitions, however, this distinction introduces new fuzziness even as it is aims for precision. After all, for many decades into the 20th century, the drawn images used to create a finished “animation” were photographed, one by one, and projected using the same medium (celluloid film strips) with the same projectors deployed for exhibiting “film.” Here for example is an early animated film by the French artist Émile Cohl entitled Fantasmagorie (1908):

As you can see, the film opens with the artist’s hand drawing, and the drawing then “comes to life.” This was a common device in the earliest animations (see, for example, J. Stuart Blackton’s Humorous Phases of Funny Faces [1906]), and a blend of photographic film and hand-drawn animation would be featured in many early animated films—including the pre-Mickey Mouse “Alice Comedies” by Walt Disney.

All of which is to say that the distinction between “film” and “animation”—so important to the development of film analysis and criticism—came later, and, as we will see towards the end of our time together, it is a distinction that might well dissolve within the next few decades. For now, however, most critics maintain a definition of film, however contested and unsatisfying, as something distinct from animation. For example, here is the definition of film in the most recent Oxford English Dictionary:

A representation of a story or event recorded on film or, in later use, in digital form, and shown as moving images in a cinema or (latterly) on television, video, the internet, etc.

There is a lot here that is worth pausing over, but for our purposes here I want to focus just on the first phrase: “a representation of a story or event recorded on film.” Aside from the intriguing tautology (a film is recorded on film?), we note two key elements here: 1) a story or event and 2) a recording. Here we see how our common definitions of film or movies (terms we will use interchangeably in this class) presume narrative (either a fictional story performed, or an actual event recorded) and a recording camera (and, after the introduction of sound in 1927, microphones).

Later, we will spend time exploring (and complicating) all of the elements of this basic definition. True, it seems to push animation and non-narrative film (such as experimental film) to the margins. True, it is so flexible that it seems to cover everything from television to TikTok videos, which most of us would not define as “film” (at least, not yet). But there is no reason to cast out the definition, because it does what all definitions do: it gets us to a starting line from which conversations about our object of study can begin. And it allows us to understand why film history largely ignores the zoetrope and the praxinoscope as possible origins, why it tends to set animation to the side as a separate category, and why non-narrative film remains vastly understudied in classes such as our own. There are good reasons to push back on how those fences have been erected, but it is also helpful to have a focused starting point from which to begin—a beginning that centers on the invention of photography in 1834.

As an aside, it is worth pointing out that the very notion of “recording” is quite knew in the late nineteenth century as film first takes shape. In the digital age, when seemingly anything can be translated into 0s and 1s and reproduced infinitely across a range of platforms, the notion that there was a time before technical recording and reproduction is hard to imagine. Until the 1870s, music was something only accessible through live performance. You could hear a piece of music performed numerous times, but each performance would be inevitably different. And when the performers left the auditorium, you would have only the memory of the music. The first phonographic devices demonstrated the possibility of both recording music and being able to play it back—the same piece exactly as recorded—for the first time. Thus, along with the earlier development of still photography, discussed below, the very idea of “recording” image and sound was completely new to the 19th century and would transform the 20th century and our own.

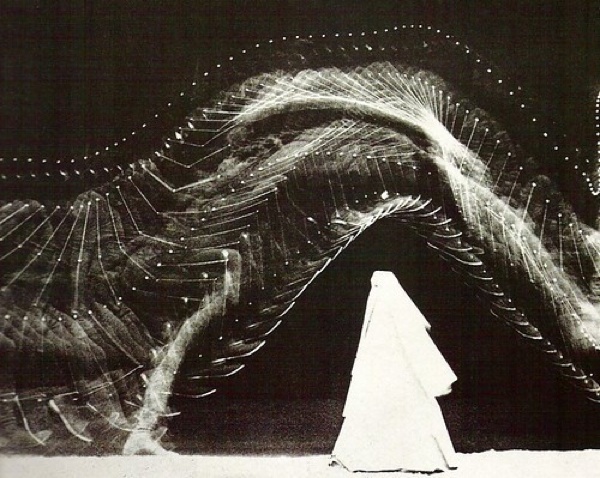

Photography was the most exciting new invention of the mid-19th century. Early photography required long exposures to get sufficient light to the photographic plate to create an image. This results in the stiff look of many Victorian photographs, as people struggled to stay still for grueling exposure times. But it also resulted in surprising discoveries: as bodies and objects moved through long exposures, interesting things happened.

- double-exposures in early photographs were often seen as evidence of ghosts

Almost immediately, photographers saw things in their photographs they had not seen while taking the picture. They saw traces of bodies in motion they had not noticed, and they began to experiment with using this new invention to capture movement. Could photography, they wondered, allow us to finally see all that so often evades the human eye?

After all, one of the important discoveries of the earlier decades of the 19th century was that the human eye was not, in fact, the pure, objective window onto the world that it had long been imagined to be. Modern stage magic, first popularized in the 1840s by the French magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, proved how easily our eyes could be fooled into seeing what was not there (and not seeing what was). In the wake of the new revelations opened up by optics and stage magicians, optical illusions became a veritable fad in the 19th century—and the optical toys discussed above are part of this obsession with the fallibility of human vision. Suddenly people began to wonder what assumptions long held to be true based on visual evidence might in fact not be true at all. For example, Peter Mark Roget, later famous for his thesaurus, in 1824 devoted himself to attempting to understand why the spokes on wagon wheels appear to warp and bend when viewed through vertical slats.[1]

Several decades later, now armed with a camera, an English photographer named Eadweard Muybridge took on a challenge from Leland Stanford, the former Governor of California (and future founder of Stanford University). Stanford wanted Muybridge to capture every aspect of his horse’s movement while trotting, something that the human eye cannot see. Up until this time, artists could only guess as to what horses did with their feet when running (see the painting by George Stubbs below). Muybridge put the question to rest once and for all. By placing along a track several cameras triggered by trip-wires, he was able to break down the horse’s movement into precise slices of recorded time:

|

Muybridge then developed a new optical device he called the zoöpraxiscope to bring to his lectures, combining elements of the zoetrope wheel with the capacity to project the image produced onto a screen. Thus for the first time, a sequence of photographic images were projected for audiences, putting still photographs into motion on the screen. This, as opposed to the dozens of previous optical devices, would come to be understood as the “birth” of film as we know it today.

This founding moment brings us to our first key term: the frame: an individual still photograph on a strip of developed film.[2] As we watch the animated version of Muybridge’s horse above, we do not see the individual frames; when film is set in motion at sufficient frames-per-second (fps)—the standard being 24 fps—the illusion of motion is created and the discrete frames dissolve before our delightfully gullible eyes. Even though we don’t see them when a film is in motion, it is important to keep in mind that the individual frame remains the fundamental building block of everything we see on the screen. Just as the material world is made up of atoms invisible to the naked eye, so are the films we watch made up of frames we cannot see without stopping them and holding the film up to the light (as the the director Frank Capra does while consulting his editor on the right).

This founding moment brings us to our first key term: the frame: an individual still photograph on a strip of developed film.[2] As we watch the animated version of Muybridge’s horse above, we do not see the individual frames; when film is set in motion at sufficient frames-per-second (fps)—the standard being 24 fps—the illusion of motion is created and the discrete frames dissolve before our delightfully gullible eyes. Even though we don’t see them when a film is in motion, it is important to keep in mind that the individual frame remains the fundamental building block of everything we see on the screen. Just as the material world is made up of atoms invisible to the naked eye, so are the films we watch made up of frames we cannot see without stopping them and holding the film up to the light (as the the director Frank Capra does while consulting his editor on the right).

If the frame is the invisible building block of all film, the shot is the first basic element that we can see on the screen. If I were to continue to beat my earlier metaphor to death, I would describe the shot as the molecule, made up of many atoms (frames). But since our goal is to develop a way of describing and analyzing film grammar, let us instead think of the shot as the word—the foundational element of a narrative made up of words, sentences, and paragraphs.

The best way to illustrate the shot and its role at the origins of film is to return to the early films of the Lumiére brothers. Like most films from the earliest years of the new medium, the Lumiére films from this period were made up of one single shot—a continuous piece of film with no cuts. Here, for example, is arguably their most famous film, L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (1896):

There are legends that audience members in Paris ran screaming from their seats when this film was first projected. It is a great story, but there is no historical evidence to back up such an account. Nor is it convincing. After all, as we have seen, by 1898 when the film was first exhibited publicly audiences would have been very familiar with the ways in which the illusion of motion was created from long experience with optical toys and devices. They were not cave dwellers awed by magical technologies; indeed, they understood more about how this technology worked than did many filmgoers in later generations who would be increasingly removed from the technology and encouraged by Hollywood to think of film as “magic.” But if there were gasps of surprise in the audience when the film was exhibited, it was likely because the audience thought they were there to see an exhibition of projected photographs, and the thrill of seeing a photograph “come to life” was surely a delightful surprise.

This film is one shot. In fact, this is the most basic of shots, in that there is no camera movement whatsoever. Instead, all the movement on the screen is provided by the motion of the train diagonally across the frame (here used in its second meaning), from the upper right to the lower left, coupled with the disorganized movement of the waiting passengers preparing to board. The camera is fixed in place—it turns neither left nor right. The movie ends when the film reel in the camera runs out.

Throughout most of the 1890s, the Oxford English Dictionary definition of film might have read: “A representation of a story or event recorded on a single piece of continuous film.” The Lumiére brothers in particular perfected films of “events,” recordings of things as they happened in the world (the origins of what we would later call documentary). Others, such as George Méliès, quickly became interested in doing something very different with this new medium. A stage magician by profession before he became a filmmaker, Méliès was interested in the possibilities movies provided for spectacle and wonder. Where the Lumiére brothers came to film as photographers interested in capturing the world as it was, Méliès approached film with the eyes of a magician. And this led him, inevitably, to the cut.

Here, in The Mysterious Portrait (1899), we see Méliès employ a cut as a kind of sleight-of-hand, allowing seemingly impossible things to happen on the screen:

Later that same year, inspired by the events surrounding what was known as the Dreyfus Affair—the court-martial of a French officer of Jewish descent falsely accused of espionage—Méliès tried something different and radically new in the medium. He filmed a series of one minute shots of different scenes in the story, each looking very much as film had looked throughout the 1890s. But then he splices them all together into a longer 10-minute film. This was one of the first instances of a visible cut used to transport the audience from one space and moment in time to another.

In Wednesday’s class, we will expand our grammar from the frame (for metaphor’s sake, the equivalent of the droplets of ink that make up the individual words on the page) and the shot (the film equivalent of the linguistic word) and on to the scene and the sequence. We will also see the beginnings of camera movement, including the discovery/invention of the pan, the dolly and more. And with that, all the ingredients necessary to start telling long, complex stories in this new medium will taking shape. And we’re off to the races!

Playing with Film

In Chapter 1, we learned about the origins of film and its evolution from early optical devices and toys like flip books and zoetropes. The earliest films can seem odd to us over a century later in that they are so short and often involve few of the complex cinematic devices we have come to take for granted in big budget movies. But is it so different from the kinds of short films we make and share on social media today?

Find a TikTok video or make a short video of your own in which the entire film is made up of one shot. Next find a video on TikTok (or make one of your own) on a similar subject that employs at least one cut to join discrete shots together. What difference does this small but crucial change make? What are the unique advantages and limitations of a single long shot, as opposed to a video made up of several shots spliced together?

What other parallels come to mind when thinking about the world of late 19th century in which “film” was born and our own moment in the early decades of the digital age?

Media Attributions

- Kinetoscope

- Cinematographe (1895)

- Theatreoptique

- 570557

- etiennejulesmareydesignphotographyart-121f709bdef88bcca327e52ee1360f2c_h

- baronet-george-stubbs

- sallie-gardner-at-gallop-2

- zoopraxiscope1

- capra

an early motion-picture device, invented by Thomas Edison, in which the film passed behind a peephole for viewing by a single viewer

early moving-image device that produce the illusion of motion by displaying a sequence of drawings or photographs showing progressive phases of that motion by rotating a cylinder

1) an individual still photograph on a strip of developed film; 2) the composition boundary of the image; the boundary which delimits the space in which the image is composed.

a single continuous piece of film, however long or short, without cuts or optical transitions.

the movement of a camera during a SHOT (see PAN, TILT, CRANE, DOLLY, TRACKING, HAND-HELD, etc.)

a tradition in filmmaking concerned with the real world and actual events

the joining of two piece of film in the editing process, where the last frame of one piece of film is joined directly to the first frame of the next

to physically join two pieces of film together

a SHOT or series of shots depicting a single, continuous action and which takes place within one specific place or setting.

a series of SHOTS or SCENES depicting a continuous action which takes place in a succession of settings, but united by some logic of coherence

a camera movement in which the camera pivots left to right or right to left on a horizontal plane from a fixed point.

a camera movement in which the entire camera moves on a horizontal plane in space