3 Narrative: Part 1

Of the attributes that make humans exceptional among the animals of our planet, our capacity (and deep hunger) for storytelling surely ranks at the top. Storytelling defines us in fundamental ways a, and our drive to turn everything we experience and encounter into story has contributed to all that humanity has accomplished (for better and worse) in our history on this planet. And this hunger for storytelling has led to the proliferation of narrative media, from books and theater to film, television, video games, and many more.

While the reasons for our limitless addiction to story remains a subject of intense research and debate in numerous fields, one thing that we know for certain is that telling stories is fundamental to how we learn about ourselves—even how we forge our self—and how we negotiate the myriad other selves we encounter every day. Turning the events of our day into stories allows us to process and store them away as memories. Sharing those stories allows us to replay those memories for others, providing an opportunity to see how others judge our past actions (“You were so brave!”; “Aren’t you ashamed of what you did?”). And consuming other peoples’ stories allows us to learn to think outside our own selves—first, as children, to comprehend the world as made up of more than our own desires, and, later, to imagine what it would be to live in another’s mind and body. There is evidence that our desire for complex stories has grown historically with the increasing size and complexity of our communities, as stories trained us in how to “read” (imagine) the minds of other people—including the strangers we would increasingly encounter as we moved from cave to village to city to globalism.

Because I am a story-telling and -consuming creature, I like to imagine a mythical “origins” for human storytelling. This scene takes place in a cave some hundred thousand or so years before the earliest humans made the decision to begin migrating out of our first home in eastern Africa. The evolution of the earliest spoken language, combined with what was surely already a complex system of gestures and other performative forms of communication, allowed someone sitting around the cave to tell a story about something that had happened to her that day—a story, say, of the discovery of a herd of unfamiliar animals at a nearby river. As she tells the story, our pioneering storyteller stands before the cave wall, trying to describe in the shadows cast by the fire, the shape and movement of the animals—hoping to convince her clan that they should go at first light and check them out together (are they a threat? might they be food?).

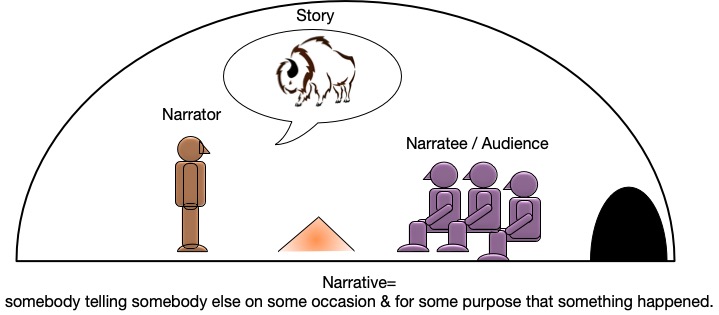

This imagined scene serves to illustrate a fundamental definition of narrative. As the influential narrative theorist (and Ohio State professor) James Phelan defines it, narrative is: “somebody telling somebody else—on some occasion and for some purpose—that something happened.” In my imagined “first” narrative, our cave-dweller is the “somebody telling” and the rest of her clan is the audience, the “somebody else.” The occasion is the nightly gathering around the fire and the something that happened is her discovery earlier that day of the herd of unfamiliar animals. The purpose, of course, is to motivate the clan to join her in seeking them out the next day.

We can map out the scene something like this:

When we think of narrative we want to keep in mind all these components:

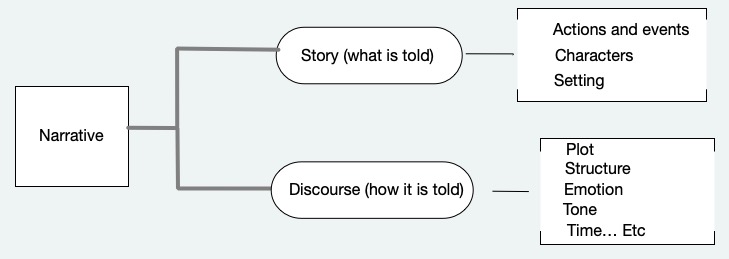

In this way we will mark an important distinction between story and narrative (although we often use the terms interchangeably in everyday use).

The story is what is being told, and it too can be broken down into a set of questions we ask ourselves as we read/see/hear the story:

- where does the story take place (setting)?

- who are the main individuals central to the story (characters)?

- what happens in the story (events)?

In our imagined prehistoric scene of storytelling, the setting is down by the river, where our narrator first saw the new animals; the characters are herself and the animals she spied from her shelter in the trees; the events are her daily journey to the river to look for groundnuts; her surprised dive for cover upon seeing the strange creatures; and what she observed of their behavior.

Of course, being new to storytelling—indeed, she is the very first ever storyteller on earth—she likely finds herself excited by her new-found role—not to mention the adrenaline still pumping from her earlier encounter. As a result, it is easy to imagine she did not tell the events in chronological order, beginning instead, as we often do when eager to grab the attention of our audience, with the punchline: “I saw huge terrifying creatures today, who might well kill us all. Or, maybe, feed us through the winter?”

“Slow down, slow down!” her audience likely responded. “Now that we apparently have the capacity to tell and understand stories, tell us what happened so we can picture it for ourselves in our minds’ eye.” And so she tried again, but even so, the past events often came out of order. At one point it was because, in the telling, she remembered that she had, in fact, discovered a large patch of groundnuts and wanted to be sure they did not lose those precious calories when next they returned to the riverbank. In another case it was because, in describing the long sharp grasses through which she passed on her way down to the river she realized these grasses resembled in certain respects the long matted hair of the animals she would spy once she arrived. Finally, sensing that her audience was starting to get bored, more interested in the nuts roasting on the fire than in her story, she jumped to the end, somewhat exaggerating the ferocity of the beasts and the dangers to which she had been exposed, hoping to win them back to her goals in telling the story in the first place.

Of course, even after millennia of telling stories, we all still do much as did my mythical first storyteller. Try as we might, it is impossible—both because of the constant rewritings of our own memory and because of our attentiveness to the waxing and waning interest of our audience—to tell each and every event that happened to us in the exact order in which it occurred. Like our prehistoric storyteller, we might begin with the ending to get attention, especially if our audience seems otherwise occupied and not in the mood for a story. “Hey!” we announce to our roommates, “I have to tell you about how my professor busted a kid in class for watching a movie… and wait until you hear what the movie was!” We have jumped ahead near the end of the story to get our roommates’ attention, but we have withheld, by way of maintaining attention, a promised final reward: the promised surprising movie the student was watching in class. Now that we have their attention, we can begin at the beginning of the story.

When discussing narrative we make a distinction between story and discourse. Story is the “what” of the story (characters, setting, events arranged in chronological order). Discourse is the “how” of the story’s telling: how the events are ordered in the telling? how the story is told in terms of voice, style, structure, duration, speed, or frequency of the telling, and other devices for telling a story.

At this point, it is easy to find oneself feeling a bit confused. In everyday conversation, we talk of a film as having a good or boring story. If we use “narrative” at all we likely use it synonymously with story. And probably never in any conversation we have ever had about film have we commented on the “discourse.” So, what is the point here of these distinctions between story, narrative, and discourse?

One of the powerful effects of film, particularly in the Hollywood narrative tradition, is that it is built so as to make us forget that what we are experiencing is a story being told. Some of this is due to the fact that we are working with a photographic medium, and so what we see on screen involves real people, real objects such as we might see in everyday life, or, when the settings or story is fantastical, one which is so convincingly recreated on screen as to seem as if it could have been recorded from some alternate reality. When watching a play we can never forget for more than a short period that we are watching actors perform on a bounded stage, with manufactured sets, artificial lighting, etc. After all, we see the stage and its limits, we see the lights overhead, we see the stagehands lowering the new sets between acts. Similarly, when we are reading a novel—however immersed we might be—we don’t lose sight for long of the fact that the images in our head summoned by the novel are in fact made up of words, printed on paper, in a book we hold in our hands.

For most of the twentieth century, movies were watched primarily in darkened theaters. Audiences were gently but effectively disciplined to maintain silence throughout the film, to remains in their seats, and to ignore the fact that the film they were watching was taking place on a screen of dimensions every bit as limited as the theatrical stage. We will talk at length in the weeks ahead about various factors that contribute to the unique power of narrative cinema to create this sense of amnesiac immersion, including evolving techniques in sound design, set design, editing, and special effects. But even when cinema was in its early stages, commentators noted this odd power as something with potential to do amazing—or horrible—things.

- 1912 movie theater slides educating early film audiences on how to behave

- A 21st-century AMC theater reminder to be silent

Writing in 1936 in an essay we will return to again later, the German cultural critical Walter Benjamin meditated on the unprecedented impact of film on audience:

The shooting of a film … affords a spectacle unimaginable anywhere at any time before this. It presents a process in which it is impossible to assign to a spectator a viewpoint which would exclude from the actual scene such extraneous accessories as camera equipment, lighting machinery, staff assistants, etc. – unless his eye were on a line parallel with the lens. This circumstance, more than any other, renders superficial and insignificant any possible similarity between a scene in the studio and one on the stage. In the theater one is well aware of the place from which the play cannot immediately be detected as illusionary. There is no such place for the movie scene that is being shot. Its illusionary nature is that of the second degree, the result of cutting. That is to say, in the studio the mechanical equipment has penetrated so deeply into reality that its pure aspect freed from the foreign substance of equipment is the result of a special procedure, namely, the shooting by the specially adjusted camera and the mounting of the shot together with other similar ones. The equipment-free aspect of reality here has become the height of artifice; the sight of immediate reality has become an orchid in the land of technology.

We will spend time unpacking this and related observations by Benjamin later in the course, but for now let us focus on his ambivalent recognition of the fact that film is doing something different than other narrative media and forms that had preceded it. In an essay considering “the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction,” Benjamin marvels at how film—the most technologically mediated narrative media ever invented—manages to make the vast technologies involved in every aspect of its production dissolve in favor of an illusory “reality.” In a modern world in which mechanical reproduction is everywhere, as it was for Benjamin in the 1930s and as it is only more for us in the 2020s, film’s ability to hide its “apparatus” and create an illusion of immediate reality is a remarkable source of power, one whose appeal he compared to “an orchid in the land of technology.”

It is this remarkable power of film that likely first drew us to the medium. But it is also one of our biggest obstacles as students of the medium. If film is deliberately cinstructed so as to obscure the machines and techniques that contribute to its construction, how can we hope to take it apart, to “reverse engineer” its making so we can understand the decisions that went into its final form?

Each week we will develop and refine different tools to do this work from every stage through to the last steps of the post-production process before a movie heads out to theaters. But we start with one of the hardest—narrative—because it is here that film begins (screenplay) and ends (final film), and film’s special power to present narrative as reality makes this a particularly heady challenge. But we have two weeks to explore narrative theory and film, and it is something we will keep working on even as we move deeper into the production process. Let’s begin by considering some examples of ways of clarifying the distinction between story and discourse in order to better understand the complexity of narrative’s making.

**

In the film Rashomon (dir. Akira Kurosawa, 1951) key events are told multiple times by different narrators within the larger frame of the story. So unique was this approach to film at that time that it became its own shorthand: “the Rashomon affect,” describing the ways in which participants in a series events can narrate those events so differently as to effectively result in completely different stories of the same events. Films such as Gone Girl (dir. David Fincher; 2014), Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (dir. Jim Jarmusch; 1999), and The Usual Suspects (dir. Bryan Singer, 1995) can all be described as “Rashomon effect” movies. One of my favorite example of the adaptation of Rashomon’s approach to multiple telling of the same events from different character-narrators within the storyworld is an underrated animated feature from 2005, Hoodwinked, which combines Rashomon’s discursive approach with the familiar Red Riding Hood story, allowing Wolf, grandmother, woodsman, and Red herself to all give very different versions of the events of the fateful day.

Technically, we call this iterative narration, a term used to describe the repeated narration of a single series of events (singulative narration being the traditional version of telling the series of events only once). But for film folks like us “Rashomon effect” works as well.

Iterative narrative is an extreme example of how story and discourse can be very different. But even with films telling events in a straightforward, chronological way we will find that story and discourse are never identical. As mentioned earlier, story is the “what” of the story, the raw material that is transformed by the teller (in our case, the filmmakers) into the film, translated by discourse into narrative. The transformative effect of discourse is often clearest in the difference between the events as they happened and the events as they are told. I am sure we can all think of examples of films that foreground such differences, but if you have seen it (or even heard it described), one of the first films that likely comes to mind is Memento (dir. Christopher Nolan; 2000). The film alternates between scenes taking place in what appears to be an earlier time and scenes that take place in our narrative present (the first are filmed in black and white, and the second in color). We would quickly adjust to this alternating rhythm were it not for one more twist of the chronological screw: the color scenes are presented in reverse chronological order, such that the final event plays first, and each subsequent color scene moves to an earlier event in the chronological story, until eventually it meets up with the “end” of the timeline of the events represented in the black-and-white sequences (presented in chronological order) and the whole puzzle falls into place.

Memento radically rearranges story-time via the discourse of the film’s narration, challenging us to put the pieces of the time puzzle back together in their “proper” order. I recall when the film came out, some critics wondered why anyone would want to work so hard for a movie. Turns out we very much enjoy doing so. Almost immediately, fans began diagramming the unique narrative structure of the film, sharing insights and discoveries that emerged from multiple viewings.

A series of similar puzzle films sprung up after 1999, not coincidentally the first year in which the DVD became widely commercially available. With this new digital technology, for the first time film viewers could replay a movie frame-by-frame, in any order they desired. In the case of the first DVD edition of Memento, the producers offered the option to play the film in the “correct” narrative order, seemingly anxious that people would be put off by the demands of the film on its audience. They were wrong, and the film has remained popular more than twenty years later and helped spawn a cycle of “puzzle films” (not surprisingly, the chronological viewing option dropped from subsequent editions of the Memento DVD).

Our capacity to translate even byzantine discursive machinations back into the regular chronology of story is one of our lesser-appreciated superpowers—and it turns out to be one we unconsciously look for opportunities to exercise. Mulholland Drive (dir. David Lynch; 2001), The Sixth Sense (dir. M. Night Shyamalan; 1999), and Run Lola Run (dir. Tom Tykwer; 1999) all make similar demands on the viewer. While the puzzle film might at first seem to have receded in prominence from those early years of the digital revolution, we can recognize its afterlife in the ongoing cycle of time travel and time-loop films from the past decade or so (see some examples in the sidebar). Clearly, new technologies for viewing and other cultural and technological changes in our everyday lives have unlocked a growing appetite for narratives which play complicated games with story-time.

Even without such elaborate narrative constructions, however, time is being played with in virtually every movie in ways crucial to the narrative economy of films—bound by convention by fairly firm running-time limits of around 2 1/2 hours. Flashbacks and flash-forwards) are common devices in narrative film, for example. See, for example, the scene below from Oldboy (dir. Park Chan-wook; 2003) in which a character recalls his sister’s death during an elevator ride which ends, back in the present, with his suicide.

More often, however, time is played with in more subtle ways. Look at the opening of Alien (dir. Ridley Scott; 1979) below. At first it seems as if there is a pretty much 1:1 relationship between the running time of the film and the events that happen on the screen. Upon closer examination, however, we see that, as the crew begins to awaken from their cryogenic slumber, an editing technique called dissolves is used to subtly move the passage of story-time forward. While dissolves often serve as transitions between different scenes (as we saw in The Lost Child [1904]), they can also be used—as here—within a scene to gently pass over time. Here the camera remains focused on the crew and the dissolves indicate the passage of time, suggesting that things are being left out of the telling because the process of waking up from intergalactic deep-sleep is too long and slow to show in full on screen.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PD7K4dCSoyo

Other moments of dropped time are less easily identified because they don’t call attention to themselves with devices like the dissolve above. Think about Scream from last week. How long was the party at the end of the movie? We see Sydney enter the house party right around an hour into the film. The house and its environs will be the setting for the rest of the movie, roughly another 40 minutes of screen time. Clearly the party and the bloody resolution in the house occupies much more than 40 minutes in story time. After all, it is dawn when we move to our final shot outside the house, with Gail Weathers rehearsing her big moment. And yet where did the missing hours go? Here the story time that ends up on the discursive cutting room floor is not marked by dissolves or anything that calls attention to the omissions. The edits effectively slight-of-hand it out of mind, skipping over the unnecessary time watching drunk teenagers be drunk teenagers so we can get more quickly to the stuff that will bring the film in on time.

Time is constantly skipped, dropped, elided throughout the vast majority of movies. Sometimes the film calls attention to these gaps—clearly marking time markers to show that we have moved the clock forward. But most of the time, we don’t notice—at least not the first time through—how events are dropped in order to move the story along. After all, as Erich von Stroheim learned the hard way with Greed back in 1925, commercial movies have limits when it comes to running time. A film is going to be on the whole around two hours, give or take a half-hour. Few stories that make their way to the screen describe events that take place, from start to finish, in two hours. So some things have to go, time has to travel, and we are along for the ride.

The place where skipped time is buried in narrative is called an ellipsis—a gap, the dropping out of an event from the story by the narrator. While this is often done to move things along, it can also be done to withhold information for a later reveal. Whatever the reason for its use, however, ellipsis is a key example of how narrative discourse plays with time. While many films do their best to hide the ellipses in order to preserve the illusion of events transpiring before our eyes that is key to the dominant tradition of Western narrative film, they are almost always there and spotted if we look out for them. There are exceptions—what we call “real-time” films, in which the story-time and the film’s run-time are effectively identical (some of my favorite examples examples are in the sidebar). But in the world of narrative cinema these are truly exceptional—deliberate experiments with the conventions of narrative film (Cléo de 5 à 7, Russian Ark, or Timecode) or adapted from stage plays where the conventions of real-time storytelling are more naturally suited due to its nature as live performance (Rope, 12 Angry Men).

If one-to-one equivalence of screen-time or narrative time (the time it takes the film to tell the story) and story-time (the amount of time covered by the narrated and implied events) is the exception, then the rule of film is that these two are not in sync. In most films, story-time is longer—sometimes much longer. But it can, at least theoretically, also be shorter: imagine film about a basketball game projected in slow motion, in which 10 minutes of the game take up 90 minutes of screen-time. This is another way in which discourse can do its work with time in a film: speed. A fast motion film of a flower growing can describe weeks of time in a matter of minutes, just as a slow motion film can have the opposite effect. The speed at which the film represents events on the screen—usually close to “real-time” within any given scene—can be modified along with temporal gaps and leaps and iterative rewindings and loops.

Some of these techniques we will discuss in more detail from a technical view point later in the course, but for now it is useful to review and categorize some of the ways in which narrative discourse can take the raw material of a story and modify it into the narrative film we see on screen. We can think about the ways in which film discourse conveys a long storytime in an economical screen time, those where story-time is longer than screen-time, as examples of summary: discourse (the telling of the story) is shorter than the events told. Summary can be achieved through a number of techniques. For example, in addition to ellipses, as discussed above, filmmakers can also use montage sequences. Montage sequences were commonly used in older narrative film to skip the tedium and repetitions of a long training sequence, for example. While today they are often treated as an object of satire, as in the montage sequence from Team America: World Police (dir. Trey Parker; 2004) below, they continue to be widely used, if with a bit more subtlety than this example:

Within individual shots and most scenes, unless fast or slow motion is deployed, story-time and discourse time are assumed to be 1:1, the ellipsis or gaps being buried in the cuts between scenes. This is part of what contributes to our experience when watching films of events happening in real time before our eyes. And while it is very rare to have an entire film in which discourse-time is longer than story-time, it is quite common for this to be the case in part of a film (a scene or sequence). If we refer to a scene in which discourse time is shorter than story-time as summary, a scene in which discourse time is longer than story-time is referred to as a stretch scene. A deliciously violent example can be seen in the teahouse shootout in Hard Boiled (dir. John Woo; 1992):

While in general in narrative film, discourse time is yoked to story-time explicitly—as real-time scene, summary scene, or stretch scene—in contemporary films we occasionally will have breaks in story-time in which the film becomes, effectively, pure discourse disconnected from story. In narrative terms we call this a pause. In novels such pauses are common: the narrator pauses to address the reader directly about something unrelated to story-time. In film it is rare enough that a couple of examples will help make it clearer. Below are two scenes—from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (dir. John Hughes; 1986) and Annie Hall (dir. Woody Allen; 1977) that brilliantly illustrate the concept of the pause:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jRcMsqCbzWk

Here is a distillation of these concepts, for those of us, like me, who like tables

| Term | Definition | Example |

| scene/real-time | story-time and discourse-time are equal | most scenes and all shots (not using fast- or slow-motion within narrative film |

| summary /speed-up | story-time is longer than discourse-time | a montage sequence; a fast-forward shot |

| stretch/slow-down | discourse-time is longer than story-time | slow-motion shot |

| ellipsis | discourse-time jumps to a later part in story-time | the sudden movement forward, usually at a cut between scenes; this can be explicitly suggested or only understood by the viewer retroactively |

| pause | Story-time stops while discourse time continues | rare in most commercial narrative film than it is in the novel, but we see examples of it in meta-narratives when a narrator within the film pauses the story to comment on the telling of the story itself |

Discourse can be contracted and expanded in relation to story-time using these techniques, but as we saw it can also be rearranged, told out of order—through the use of flashbacks and flash forwards, for example. This can also happen through less obviously telegraphed techniques, as in Memento or films like Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994), both directed by Quentin Tarantino. Here we have films which deploy anachrony—when discourse time is deliberately in a different order than story-time throughout the whole of the film. (We will definitely see this at play in our film next week .)

Finally, as we saw early in this chapter and will explore in more detail with Rashomon this week and Citizen Kane later in the semester, we need to attend to narrative frequency: how often an event is told. Many memorable films deploy examples of telling the same events a second time, often to reveal something we did not properly grasp the first time through, as in the ending of Sixth Sense when we realize that we have been seeing the events of the film over the shoulder of a dead man. This technique is especially effective in films with unreliable character-narrators.

These are just a few of the ways in which discourse transforms story into the narrative we see on screen, but these are important ones and a great place to start as we dive into the hard work of analyzing film discourse. How the event as it would have been lived in real time is always different thing from what we actually see on screen. That doesn’t mean the story is not important, or that the discourse is deceiving us with its manipulations. All narrative does this. It has to. Returning to our early hypothetical example, were you to try and retell every moment of your day to your roommates they would all retreat to their rooms (and probably start looking for a new roommate). But even if you could force them to listen—and even if your memory were flawless—you would of course not be repeating the events themselves. Instead, you would be translating the lived events of your day past into oral narrative, using words to try and convey visual elements of the day—or your voice to mimic the sound of an alarm or a car backfiring. You would be relying on memory, which transforms lived experience into certain kinds of narrative data. The raw materials of the thing you want to tell—the story—is translated through discourse the minute we start to tell it.

This is true in film as well, even though we sometimes are encouraged to forgot it. Film’s unique combination of moving images, sounds, and speech can make it feel as if it is going through fewer filters requiring translation. When we tell a story as a novel (which cannot reproduce images or sound) or in a comic book (which cannot reproduce sound and which can use text only sparingly) we are clearly aware that the medium itself requires translation to turn story into narrative. But it can often seem that film is more transparent, more direct. In fact, the opposite is most often the case: no narrative medium requires more technology, is more dependent on editing and other post-production processes, or demands more collaboration by creative individuals, each with their own with unique visions and voices.

But this illusion of transparency is powerful indeed: it is part of what makes film uniquely affecting and in some cases challenging to dissect. Early on filmmakers realized that film can create an “immersive” experience, creating the illusion not just of motion but of providing the viewer a voyeuristic perfect window on events transpiring directly in front of them. This is where attending to narrative discourse helps us early in our course of study. It helps remind us at every turn that we are not seeing “live” unmediated events on the screen; it keeps us attentive to the complicated discourse of many hands are recording, cutting, and shaping the story we see on screen (actors, directors, sound designers, editors, etc); and it trains us to attend to all the ways in which the how of the telling starts to reveal itself in the gaps, the repetitions, all the moments when story-time and discourse are not aligned. Only then can we begin to see the film as it truly is: a remarkable moment in the history of human narrative that employs its magic to make us forget, however briefly, the fundamental definition of narrative: “somebody telling somebody else—on some occasion and for some purpose—that something happened.”

Playing with Film

When we tell a story about an event that took place over several hours to a friend, we know they will not sit patiently for several hours as we tell it exactly as it unfolded in time. And so we provide markers in our story to let them know what we are skipping: “I walked and walked until my feet were sore,” for example, says in a few words what must have taken a few hours of repetitive marching. “I slept fitfully, but nonetheless the next morning I felt better,” allows us to skip the long night and get to morning where the interest of the story lies. We never once, in listening to such a story, are unaware of the condensations and elisions, or of the fact that the narrative time (the time it takes to tell the story) is much shorter than the “story time” (the time covered by the narrative).

- Yes, when we watch movies—especially in the Hollywood narrative tradition—we often don’t notice the compressions and elisions. Looking back at Scream, identify a cut in which time has clearly passed between scenes but which you did not attend to in watching it. How does it achieve its effect? How much time do you imagine might have passed between the two scenes? What might have occurred that is not shown on the screen?

- Can you think of other films than those discussed in the chapter that deliberately deploy anachrony—telling a story out of chronological order? How does it work in this film? What clues is the viewer given to put it back together?

- Can you think of other examples of pauses, as defined by the examples in this chapter?

- We talked briefly about Porter’s Life of an American Fireman (1903) during week 1. As I mentioned, when the film was rediscovered by an archivist at the Museum of Modern Art in the 1940s, he assumed the film was assembled wrong and he cut between the two versions of the fire and rescue so the interior and exterior tellings were woven into one telling integrating two spaces (inside the house and outside). This turned out to not be what Porter intended, and the version we have linked to on our syllabus is the correct one as he intended. The story is told from one perspective. And then it is retold again from another. It is, in fact, the first example of an iterative narrative in film. What is the effect of this iterative (repeated) storytelling here? Can you think of other films or TV shows other than those mentioned in the chapter that employ iterative narrative?

- I offer some vague thoughts as to why we are so addicted to narrative as a species, and how the kinds of stories we are drawn to change over time. Any thoughts from the perspective of your own work in your individual majors that might provide further insight into our collective love affair with (and deep addiction to) stories?

Media Attributions

- Untitled

- narrative-discourse-story

- Memento1

the teller of the story

the audience directly addressed by the narrator (in narrative theory not identical to AUDIENCE, but for our purposes here often can be used as equivalent terms)

people watching a movie at a screening; when used in a narrative context, the imagined recipient of the story being told

the time and place in which the movie’s story occurs, including landscape, social structures, climate, cultural attitudes, customs, and norms..

individual within film, played by an actor; in narrative theory, an entity with agency in a storyworld.

the complete chronological sequence of interconnected events in a film or other narrative form

a scene or sequence from the storyworld's "past" which is inserted into a scene in the "present" time of the story

the opposite of a FLASHBACK

an optical effect in which one end of a shot is gradually merged into the beginning of the next by the SUPERIMPOSITION of a FADE-OUT over a FADE-IN

narrative device of omitting a portion of the sequence of events

film photographed at less than 24 frames per second so that things appear to move faster when projected at 24 fps.

the film runs through the camera at faster than normal rate (also called "overcranking"), so that when projected the action will seem to move slower

Transitional sequences of rapidly edited images, used to suggest the lapse of time or the repetition of certain actions.

a discrepancy between the order of events in a story and the order in which they are presented in the discourse