1 Module 1: Orientations to East Asia

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

OUTLINE

OVERVIEW

The goal of this course is to introduce you to the cultural areas of East Asia—China, Korea, and Japan—through the lens of the humanities. The ideal of a humanist education—meaning a well-rounded education in literature, philosophy, calligraphy, art, archery, chess, and other pursuits—has been key to an ideology of “self-cultivation” in East Asia since ancient times. Self-cultivation is a concept that, whether explicitly or implicitly, still resonates today in new, often more inclusive forms throughout the region. In many ways, this orientation towards learning parallels ideas developed in the ancient Mediterranean world, which are now undergoing interrogation and evolution in new social contexts in the West. In this text, we use a broad, inclusive definition of the humanities, understanding it as the sort of learning that contributes to the formation of productive global citizens in a just world. We will be examining select aspects of the humanities as a way to enrich our experiences as humans on earth as well as to see how these cultural features inform the cultures that produced them. We will also note how governments and private industry attempt to wield “attractive” forms of traditional and contemporary culture in the creation of what Joseph Nye has called “soft power” to achieve local, national, and global outcomes (2004:5-7). Aspects of history and culture, worldview, modern lifestyles, technology, language, literature, art, popular culture, and folklore relating in various ways to present-day East Asia constitute the focus of this book. Because of the increasingly central role East Asia plays on the global stage, it is crucial that people everywhere better understand and acknowledge this part of the world and its many cultural contributions.

Since the 1950s, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea—and in more recent years the People’s Republic of China—have been among the places leading the world in economic growth. In the twenty-first century, East Asia has taken an increasingly central role in the world economy, global power, and cultural production, sharing the spotlight with India and parts of Southeast Asia. In the coming decades, it is likely that these places will continue to offer the rest of the world unrelenting competition in virtually all fields.

Japan presently has the third-largest economy after the United States and China, and despite recent challenges China has aspirations to overtake the United States as the world’s largest economy. The United States and China are now the world’s largest energy consumers, with Japan also near the top. In terms of crude oil consumption, China, India, Japan, and South Korea rank in the top ten consumers, led by the United States. China and the United States are also the leading producers of carbon dioxide contributing to global warming. In a growing number of areas, such as percentage of world meat consumed, amount of concrete used, etc., Chinese consumption figures are number one.

In terms of education, Japan and South Korea have literacy rates above 98%—on par with the northern European Scandinavian countries as the highest on earth. China is implementing a far-reaching overhaul of its university-based research and development training programs and is implementing reforms to re-vitalize education in less-developed rural areas. With its highly literate society and a technology-savvy public, South Korea leads the world in broad-band Internet access and is a leader in technological innovation. Expanding manufacturing and consumption of materials goods such as automobiles and cosmetic products reflect robust consumer economies. Investment in robotics, artificial intelligence, eco-cities, high-speed rail, mega-agriculture, genetic engineering, immunology, and space exploration point towards sustained growth and innovation in East Asia and consequent influence on neighboring countries in the Asian-Pacific region and beyond.

Behind this recent rise to global prominence are the long histories and rich legacies of the East Asian cultures, aspects of which are often still inadequately understood or even misperceived in other parts of the world, including the United States. Therefore, a basic introduction to the region’s past, its rapidly changing present, and its cultural contributions to humanity is crucial for developing a useful awareness and appreciation of East Asia’s role in the world today.

It is only by developing constructive cultural awareness among and between the peoples and nations of an increasingly connected and interdependent world that misperceptions and conflict can be mitigated or avoided. This is becoming more urgent as the earth’s finite supplies of oil, water, and other natural resources come under greater pressure due to rising populations and living standards around the globe. It is hoped that the introductions and insights presented in these modules will be useful for anyone traveling to, living in, working in, or pursuing continued studies of East Asia (which may very well be YOU at some point).

Whatever the case, opportunities are increasing for those with knowledge of these major players in increasingly globalized world culture and economy.

KEYWORDS

The terms discussed in this section—culture, traditions, context, and identity—underlie the basic approach that will be used to introduce the material in this course.

Culture

Most important among these terms is culture. Although this word has many meanings, our definition is simple: culture is the learned behavioral characteristics of a specific group (Nash 1989:9). Thus, culture is the complex total of all the many, varied, and layered levels of learning and knowledge of a group of people and their behavior. This basic definition of culture includes behaviors that range from the basics of language and toolmaking to cultural productions like art and literature, that is, the humanities.

It should be stressed however, that societies are made of individuals. Thus, while we can talk in general terms about Japanese, Chinese, Korean, or American culture, we should realize that individual members of a society do not behave the same way and great variation within any culture is to be expected, even in groups that place high value on conformity to social norms. Everyone grows up in one or more societies but where they are positioned and their individual experiences contribute to how they interpret, embody, act out, and negotiate the “norms” of their culture(s)—as well as how they are perceived by others. Thus, it is inaccurate and unwise to make blanket statements about what people from such and such a culture “are like.”

On the other hand, it is sometimes necessary to attempt to describe a group’s cultural traits in a more general conceptual way. Nash has observed that the idea of identifying “central tendencies that become a point of reference” is a useful approach in describing a culture and comparing it with others (Nash 1989: 9). Thus, we can talk about a particular aspect of a culture but remain aware that in different situations (or contexts) it might be conducted or viewed differently and even have a differing cultural meaning or meanings. In this text we will be examining many central tendencies in the various cultures of East Asia, as well as more localized forms of cultural expression.

Identity

|

|

|

|

Essential elements of Korean culture as formulated by the government to promote the idea of a modern society with distinct Korean traditions: Hanbok clothing, the Hangul syllabary (18th century poetry collection), talchum mask dance (monk and woman), Taekwondo (2016 Olympics), and kimchi (various hot pickled cabbage dishes). |

|

On both individual and groups levels, people develop strategies to communicate things about who they are. As a kind of globalized, transnational consumer culture spreads across the planet, local cultures inevitably become affected in a variety of ways. In many cases, local traditions are utilized (sometimes being revived from the past) to create and project new identities that on some level act like labeling in marketing schemes. One of the most interesting cultural phenomena to develop since the end of the second World War II in 1945 is the growth of global communication spurred by increasingly sophisticated technology. As the rate and volume of exchange between cultures increases, how individuals and societies project themselves to others on the world stage takes on new relevance. One development common to all the countries in East Asia is the projection of a message concerning identity. Identity is the “who you are” in relation to others like you or different from you.

In East Asia, a very common message communicated by various media (official country websites, mass media, museums, folk art performances, fashion, technological exhibitions, etc.) is that the cultures of East Asia have rich and historically deep cultural traditions yet are on the cutting edge of technological and cultural development. Along with these technological developments has come the development and spread of consumer culture throughout the world, which has raised another concern: if a computer looks the same wherever you put it, how can local cultures differentiate themselves from their neighbors?

In East Asia, as in many places, part of that answer has been to draw on cultural traditions from earlier in history and employ them in new ways. In some cases, this cultural recycling of tradition (or re-creation, or even tradition-inspired creation) has acted to preserve vestiges of culture that are rapidly changing, becoming obsolete, or disappearing.

Context

Context is the situation in which something occurs. It includes the totality of physical place, material objects, language, actions, and participants. The next time it occurs, conditions may be somewhat different. If a tea ritual is held in a very private and expensive “traditional” tea garden, the meanings are certainly somewhat different from those evoked in a tea ritual held in a department store in downtown Tokyo. Yet both are part of the general tradition of the Japanese tea ritual. The accompanying images are of Japanese tea rituals performed in different contexts in historical and modern Japan, and elsewhere.

Tradition

We often think of tradition as something that is handed down unchanged and unchanging from the past, but studies in anthropology and folklore, as well as our own observations, may suggest that traditions are not as static as we may assume at first glance. Indeed, traditions are dynamic processes which involve both continuity and change over time. In talking about various types of cultural performances (which might include anything from engaging in informal playful banter with friends, to cooking a type of food, to writing and reciting a poem) folklorist Barre Toelken’s observations on cultural traditions in general are useful:

Breaking down this statement with the example of the Japanese tea ritual, we could observe that “culture-specific materials” would include the material settings, costumes, and implements used specifically in the ritual. The “assumptions, and options” that come to bear on individual behavior would be in large part determined by how a practitioner learned the art, which is taught somewhat differently by the various styles or “schools” of tea ritual practice.

In the tea ritual, therefore, although there is great stress on continuity of tradition, the host (i.e., “artist”) performing the ritual is expected to display a degree of “inventiveness” (thus creating variation) in terms of the food served, the painted scrolls used to decorate the walls of the tearoom, and the selection of tea bowls and other items used in a specific performance of the ritual.

An important realization is that traditions change and vary over time and space. Anyone visiting East Asia will find that many of the traditions or aspects of traditions they have learned about in a general way will be different in real life situations and may also be in rapid transition, reminding us of an important caveat: never expect a culture different from the one(s) you have already experienced—East Asian or any other—to conform to your preconceptions. Approaching new places and ideas with an open mind is a vital practice for the goal of learning to process what is going on and act appropriately and effectively in whatever situations you encounter.

Intersections: Revival, Reinvention, Folkloresque, Artifying, Myth-ways

This section introduces several other key terms that in their intersection will help us understand the roles of the humanities in East Asia in the past and today and continue our discussion of tradition. These terms are “revival,” “reinvention,” “folkloresque,” “artifying,” and a term we introduce here, “myth-ways.”

As noted, tradition is being used in many exciting ways in East Asia and around the world today. Scholars in East Asia and elsewhere are studying how cultural revivals in the form of historical re-enactments, pageants, fashion shows, popular movements, local festivals, and various media venues are developing as new cultural forms that enmesh memories and living traditions with contemporary society. Some examples would include historical pageants such as the the “Festival of the Ages” (Jidai Matsuri), held in Kyoto Japan each October. The event features hundreds of participants dressed in ancient costumes who hold a procession in the older part of the city.

In China there is a craze for wearing the “Hanfu” clothing of the ancient Han dynasty that has caught on among college students, who wear specially tailored clothing on the street or at special club events.

In South Korea, there is a historical park in Namwon devoted to the legendary love story of Chunhyang, dating to the 18th century, which has also been featured in films and and online digital media. In some cases there are stark intersections between elements of the past and present.

Around the Gyeongbok Palace in Seoul, South Korea, are many shops where visitors can rent traditional costumes to wear during their tour of the palace grounds. The nearby National Folk Museum employs cutting-edge technology to enhance exhibits of traditional Korean culture.

In the case of these revivals, there is often a lot of “reinvention” of tradition. This is especially so for those items of culture that have gone out of practice, but are for whatever reason revived, or given new life in new social contexts. The example of the “Women’s script,” illustrated in Module 4 shows how a script developed by women in a county in Hunan province China has become a central force in the local tourist trade and taken on many new dimensions in the process of reinvention. In some instances traditions may even be “invented,” though often still drawing on aspects of earlier traditions, ideas, and experiences and suggesting continuity with the past (Hobsbawn and Ranger 1983:1-3).

Michael Dylan Foster, a folklorist (University of California, Davis) has suggested the term “folkloresque” to describe folk traditions that are used, sometimes in fractured form, in new, contemporary contexts, including digital media. This concept will be explored in greater depth in Module 9 in an introduction to yokai supernatural beings and how some pop singing groups in East Asia are incorporating renditions of folk culture in their performances in new twists to tradition. In a similar vein, Li Jing (Gettysburg College) has suggested the concept of “artifying” (yishuhua in Chinese) to describe traditional performance genres that re-stage and re-tell stories in ways appealing to contemporary consumers, who are often tourists.

Yang Lihui (Beijing Normal University, China), and Yoonhee Hong (Yonsei University, South Korea), are among the mythologists researching how ancient myths as related to religious beliefs of East Asia are informing and intersecting with popular culture media, government-sponsored heritage events, tourism sites, etc. All of these terms to some extent overlap, but are useful in trying to describe how traditions that once dominated in East Asia are now transmitted, revived, and re-purposed in the hyper-modern societies of East Asia today.

Myths are traditional stories recounting the actions of early gods and extraordinary beings, and in East Asia often concern the founding of peoples, cultures, and states. According to Mark Bender (The Ohio State University) and Yang Lihui, the term “myth-ways” (shenhua dao) describes the pathways and forms that traditional myths and related elements of folk belief take as they intersect in various ways with contemporary culture. The process has many manifestations in East Asia today. Examples include government-sponsored events in China, such as the elaborate celebration of the Yellow Emperor, who is tied to the origin of the Chinese people over 5,000 years ago, held annually in Zhengzhou, Henan province. The massive event, constructed from accounts of ancient myths and rituals, sends messages of unity, power, and continuity to contemporary audiences.

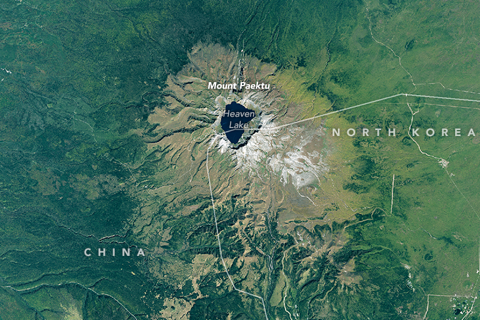

Likewise, in North Korea, there have been ceremonies held at Mt. Paektu (Baektu) to commemorate Dangun, the mythic founder of the Korean people. In some cases myths are claimed to be based on actual persons, and in some cases this is supported in the historical and archeological records. Sometimes, as in North Korea today, founders of the nation state are commemorated by monumental art, much in the manner of the memorial to Dangun.

|

|

On a popular culture level, the online South Korean “webtoon” called “Sin-gwa-ham-kke” (Along with the Gods) has become popular among young viewers. Yoonhee Hong suggests this popularity is not for its nationalistic content promoting the greatness of South Korea, but rather how the story invokes the after-death world of the gods so viewers can emotionally empathize with its characters in a setting disconnected from everyday reality.

As an example of a live performance genre (with digital parallels), some J-pop groups, such as Wagakki Band and Babymetal, have integrated traditional costumes, elements of folk religion and mythology, and instruments into their electronic music and light shows (as discussed in Module 9).

A more detailed example of myth-ways intersecting with state-of-the-art technology is the use of names by various space agencies around the world to name rockets, extra-terrestrial explorers, and space stations. Beginning in the 1950s, the USA named several of its rockets for Greek gods associated with solar bodies, planets, and constellations. These included Mercury, Gemini, Saturn, and Apollo. In the 1980s, under the direction of forward-thinking President Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese space program also decided to use names from mythology. Recent examples would include the “Yu Tu” (Jade Rabbit) lunar rover, the Chang’e rocket system, the Martian rover “Zhurong” (Fire God), and the Chinese space station, built in 2021, “Tian Gong” (Heavenly Palace). The jade rabbit is the pet of Chang’e, the moon goddess.

The Heavenly Palace refers to the abode of the Jade Emperor, the highest of the gods in folk Daoism (discussed in Module 3), and the father of the Weaving Maid (Zhi Nü). As the ancient story goes, the Weaving Maid descended to earth to bathe in a clear lake. A cowherd crept up and stole her feathered cloak. Since the Weaving Maid could not fly back to the sky, she married the cowherd and they had children. Later, the Weaving Maid found the hidden cloak and returned to the sky to visit her parents (a very filial act). But the Jade Emperor was upset and created the Milky Way, barring her from rejoining her earthling husband. Later, however, her father relented and allowed the couple to meet once a year on a bridge made out of magpies.

This reunion takes place each year on the seventh day of the seventh Lunar Month. In China the festival has been commercialized as a kind of “Valentine’s Day” (adding a cross-cultural dimension), and is celebrated in Korea as Chilseok Festival, in Japan as Tanabata Festival (Star Festival), and in Vietnam as Thất Tịch. Thus, ancient imaginings about the heavens intersect with agendas for space exploration today, enabled by space-age technology.

Why we continue to draw on elements of ancient myths today is a complicated question. Attesting to their cultural depth, Yoonhee Hong observes that, “Myths are the longest stories we tell.”

ICH

Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) projects that highlight unique cultural traditions have been given recognition by UNESCO (a program in the United Nations), with China having the most items on the list. Many of the performance traditions introduced in Module 7 are on the ICH lists. (It is interesting to note that the UNESCO lists were inspired by lists of “living cultural inheritors” made in Japan and Korea in the 1960s.) The value of these listings as “soft power” in the cultural and political dynamics of East Asia should not be underestimated. Recently, there have been disagreements between China and Mongolia over the listing of a certain epic poem (Jangar), and between China and South Korea of a folksong (“Arirang”), folk clothing (Korean “hanbok” and Chinese “Hanfu“). In each case compromises and clarifications were made after official UNESCO hearings.

Soft Power

Another perspective to consider in our examination of East Asian humanities is the phenomenon identified by William S. Nye, a Harvard professor, as “soft power” (Nye 2005:3-7) In the contemporary globalized world, governments and industry have taken notice of the “power” of “soft power”—and many manifestations of such power are created and derived from traditional folk culture, elite artistic and literary production, films, and popular culture media. Nye defines “power” as “the ability to get outcomes one wants,” and differentiates between “hard power” and “soft power.” While hard power—exemplified by military and other forms of government authority is based on coercion and threats—soft power is the process of “attracting people to want what you want.” Thus, soft power “rests on the ability to shape the preference of others.” Nye cites Hollywood movies as a prime example of American soft power and how the industry creates products that have a strong attractive force in many parts of the world. In East Asia, for instance, the attractive power of Japanese anime and the Korean Wave have become vital sources of soft power for Japan and South Korea, respectively. Nye elaborates that the attractive power of soft culture involves the “mysterious chemistry of attraction” and is hard to quantify—yet its power in creating relations between businesses, governments, and peoples is undeniable. That said, attempts at creating and wielding soft power do not always go as planned. Context, as discussed above, is an important factor, and what may work in one cultural situation, may not work in another. Soft power can also be a tool for promoting nationalistic agendas (that is, loyalty to and interests of one’s country), a dimension exemplified by governments in the region co-opting and re-casting traditional performance genres for usage in the promotion of political and social agendas. Examples of soft power, and how it is cultivated and utilized by various entities in East Asia are included in several modules, especially 2, 3, 7, and 9.

![MV] PSY- Korea (HD- 720p) - YouTube](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/1iAM30K_cHc/maxresdefault.jpg)

GEOGRAPHY

The geography of what is now termed “East Asia” has been in place far longer than the present nations’ geographical boundaries show. Because geography helps shape a region’s cultures, understanding them requires at least a basic understanding of geography. Everything from foodways, infrastructure, and economic systems to social structures, narrative traditions, and even worldviews are affected by the landscape surrounding a local culture (even yours!). Therefore, we will begin our exploration of China, Korea, and Japan by a look at their respective geographies.

Geography of China

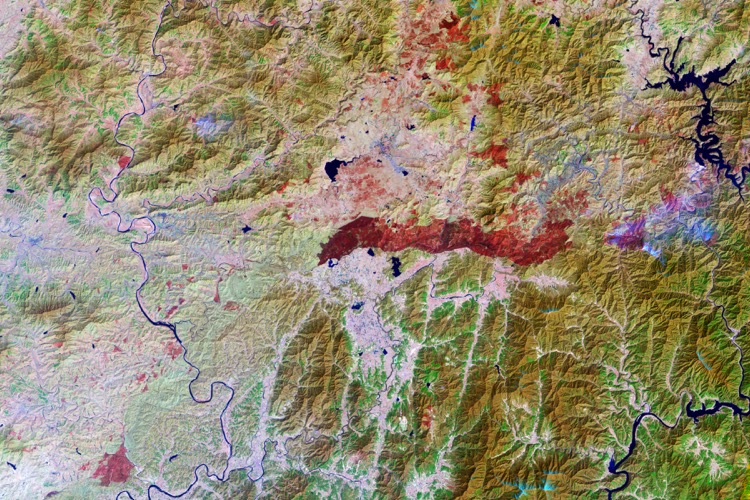

China has a very diverse geography that includes fertile river valleys, arid deserts and basins, grassy steppes, rocky broken uplands, forested hills, snow-topped mountains, and steamy jungles. While physically about the size of the United States in its total area, China has only about one-third the arable land available for agriculture. In a general sense, northern China is drier than southern China and depends on wheat more than the southern staple, rice. The following paragraphs will introduce the major geographical areas of China.

The North China Plain is a relatively flat area that covers parts of Hebei, Henan, and the Shandong peninsula. Rivers in the region include the Huai and Hai, which along with the Yellow River, flow into the Pacific. Relatively arable, the land in this region produces crops that include wheat, corn, and sugar beets. To the west of the plain is a high and dry plateau featuring eroded uplands and which cover most of Shaanxi and Shanxi provinces. Dominated by the Yellow River, the area is known as the Loess Plateau, with the dusty, yellow soil known as “loess” giving China’s second longest river its name. In early times, vast forests covered part of both the Plain and Plateau areas, though they have long been obliterated by at least five thousand years of human habitation.

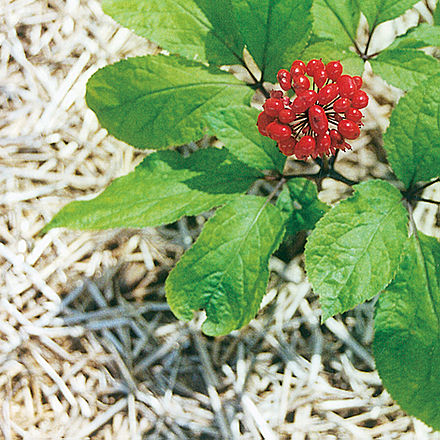

Northeast China, once known as Manchuria, being the homeland of the Manchu (Manju) people, is bordered by Siberia to the north, North Korea to the east, and Inner Mongolia to the West. Major Rivers include the Heilongjiang or Amur River, the Songhua River, and Yalu River (which the Koreans called the Amnok River). Large forests of evergreens and northern deciduous trees once covered the area and even today some parts of the region contain rich black soil. Well-watered by summers rains and deep winter snows, the area is an important Chinese agriculture region famous for producing especially tasty rice. The Greater Xing’an Forest also in this region is the largest remaining forested area in China today and is home to a few dozen of the remaining Manchurian tigers, as well as sika deer, otters, martens, foxes, eagles, moose, and other animals. The forests are also home to China’s ginseng farming industry. Wild ginseng plants are very rare and command huge prices.

Northwest China is characterized by little rainfall, expansive deserts, and plains. Parts of the vast, barren landscapes of the Taklamakan desert and Tarim Basin are reminiscent of recent photographs from Mars. The Silk Road stretched across this seemingly endless territory, moving from oasis to oasis, including the city of Turpan in the Tarim Basin, which bakes in temperatures that rise above 48°Centigrade (over 120° Fahrenheit!) in the second lowest desert basin (154 meters below sea level) on earth.

|

|

|

The Hexi Corridor is a narrow strip of desert that runs through mountains in narrow Gansu province containing routes that lead into Xi’an (once the ancient capital of China) in today’s Shaanxi province. Another major desert is the Gobi, which lies north of Gansu and the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and comprises part of western Inner Mongolia. Prominent mountain ranges in this region include ranges of the Tianshan and Kunlun Mountains in Xinjiang.

Western China is a mountainous land spanned by several of Asia’s largest rivers. The sources of the Yellow River, which courses through the North China Plain, and the Yangzi River, which runs through southern China, lie only a few kilometers apart in the eastern part of the Tibetan Plateau, which is the highest desert region on earth. The watersheds of these major rivers are determined by the Qinling Mountains. Headwaters of the Salween (or Nu in Chinese), the Mekong (or Lancang in Chinese), and the Red rivers that flow into Southeast Asia are also in this same general region of southwest China. All these rivers are in various ways subject to development.

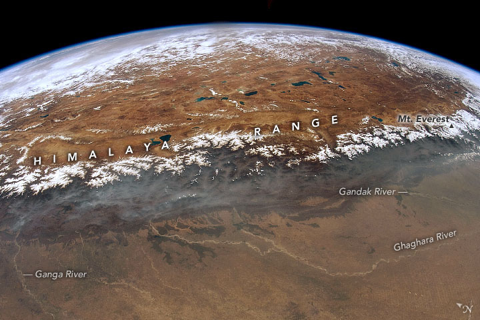

The Himalaya are the highest mountain range on earth and form part of the borders between China, India, Nepal, and Bhutan. Mount Everest (or “Qomolangmu” in Tibetanized Chinese and “Chomolungma” in Tibetan) straddles the border of Nepal and China, reaching 8,850 meters (29,035 feet) in height. The world’s highest major river, the Yarlungzangbo, flows off the Tibetan Plateau into the Indian Ocean. The Yarlungzangbo Gorge is the world’s deepest river gorge at 5,382 meters in depth.

Aside from the Xizang Tibetan Autonomous Region, southwestern China also includes Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou provinces, as well as the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Vast areas of these tracts are covered with broken uplands in the form of red earth hills or limestone karst formations. The fantastical karst formations extend into Southeast Asia all the way to Thailand.

The Greater and Lesser Cool Mountains of Sichuan and northern Yunnan provinces are among the highest ranges in the foothills of the Himalayas. The Sichuan basin is the largest and most populous of the fertile lowlands in the southwest and the site of Chengdu, the provincial capital. In the mountains north of Chengdu is the Jiuzhaigou (Nine Village Gulch) National Park, an area of unsurpassed natural beauty in China.

Jiuzhaigou (Zitsa Degu, in Tibetan) National Park is in northern Sichuan and is in some ways like Yellowstone Park in the western United States. The area of the Jiuzhaigou Nature Reserve is approximately 60,000 hectares. Among the natural features are conifer and deciduous forests, rocky mountains, clear running steams, waterfalls, turquoise-colored lakes, calcified trees, and schools of native trout (locally called “naked fish” because of their tiny scales). Although some Tibetan style hotels have been built in the park—including the gigantic Intercontinental/Paradise Hotel, which is in the shape of a nomad’s tent—the park is well regulated and staffed with a large force of young rangers, some of whom are local Tibetans familiar with the area’s flora and fauna. Near Jiuzhaigou Park are the Huanglong (Yellow Dragon) natural springs. The water in these pools, a series of calcified terraces that descend along a valley beneath a cluster of snowy peaks, changes color in an unbelievable array of shades of blue and turquoise depending on the sunlight. Two temples, one Buddhist and one Daoist, stand at the foot of the mountains, blending in with the natural scenery. As in Jiuzhaigou, millions of visitors a year wind their way through the natural landscape on carefully built wooden walkways. Near the top of the walkway is an oxygen station for hikers who need a boost in the high altitude.

Among the animal life in Sichuan are the greater and lesser pandas and the weird takin (Budorcus taxicolor tibetana) an animal something like a cross between an antelope, a goat, and a proboscis monkey. Other animals from the Southwest and Tibet include white-lipped deer, water deer (which have no antlers, but two long fangs!), tufted deer, musk deer, snow leopards, and golden monkeys. (In recent years, the Chinese government has introduced a lottery to manage the hunting of certain animals, including the takin—which costs $28,000 for a winning ticket—deer, and wild sheep.)

Areas south of the Yunnan plateau on the borders of Laos and Myanmar (Burma) are characterized by high rainfall and a semitropical climate. Up on the plateau, Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province, has a mild climate and is known for its year-round springtime weather. A vast wealth of flowers (such as rhododendrons and camellias) and medicinal herbs are found in the forests of Yunnan and Sichuan.

The Southeast is China’s most populous region. It includes the Yangzi River delta near Shanghai (Jiangsu, Anhui, and Zhejiang provinces) as well as the culturally diverse provinces of Hunan, Fujian, and Guangdong. The Southeast is characterized by low mountains and divided by rivers with wide, rich bottomlands and coastal plains. The Yangzi delta has long been an important agricultural area and is known as the “land of fish and rice.” Huge rice fields are common sites throughout the region, the more southerly zones of Guangdong and nearby Hong Kong having a semitropical climate.

Seasonal monsoon rains come in spring and fall all throughout the region. In Shanghai, the winters bring occasional light snowfalls and moderately cold damp weather. Summers are hot and humid everywhere in the region, and several cities, such as the inland city of Wuhan in Hubei province, are known as “furnaces.” The Zhujiang (Pearl River) runs through Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong province.

|

|

The climate in Taiwan and Hainan is humid in summer. Both islands feature a mix of mountains and arable lowlands. In recent years Hainan’s beaches near the Sanya resort area have helped stimulate tourism. Mount Alishan, Sun Moon Lake, and the Taroko Gorges—site of the marble industry—are well-known natural wonders in Taiwan. The Sun Moon Lake area was destroyed in the massive earthquake of September 2001, though historical monuments and tourist facilities have been rebuilt. Near scenic Mount Alishan is Mount Jade (3,952 meters), the highest mountain in Taiwan.

It should be noted that maps printed in the People’s Republic of China (recognized by the United Nations as the sole government of China) claim less territory for China than maps printed in Taiwan — the Taiwan version claims the Republic of Mongolia as part of the Republic of China (now claimed to exist only in Taiwan).

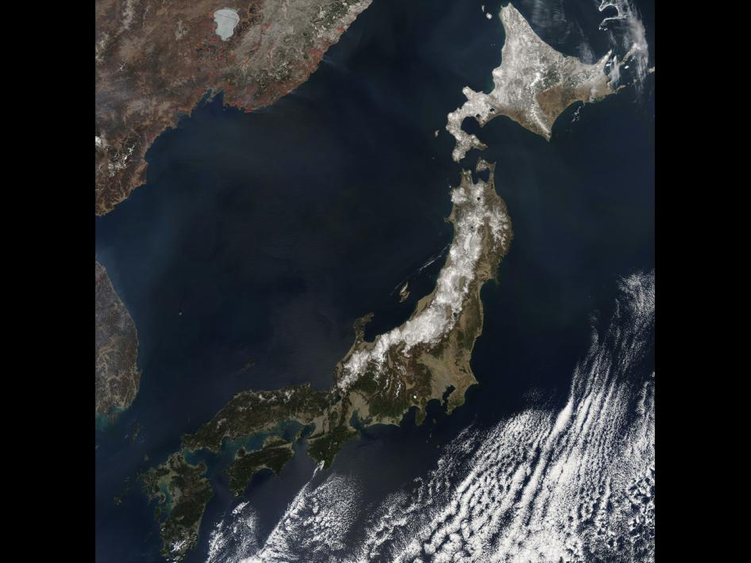

Geography of Korea

The Korean peninsula is situated on the eastern end of the Asian landmass between the islands of Japan and Northeast China. It is bordered to the east by what Koreans call the East Sea (Sea of Japan) and to the west by the Yellow Sea, which North Koreans call the “Korea Bay.” The Tsushima Strait divides the Korean Peninsula from the main islands of Japan, about 200 kilometers. About 3,579 islands are found off the Korean coastline, which stretches for a total length of 8,460 kilometers. The coast on the western side of the Korean peninsula has a very irregular contour. The Korean peninsula is geologically more stable than either Northeast China or Japan, regions that both have a history of serious earthquake activity.

A Demarcation Line that divides North and South Korea runs along the 38th parallel. The line lies within a 4,000-meter-wide Demilitarized Zone known as the DMZ. About 55 percent of the peninsula’s 220,847 square kilometers are in North Korea, which borders China along the Amnok (or Yalu River in Chinese) and shares a 17-kilometer border with Russia. The remaining 45 percent of the peninsula, comprising 98,477 square kilometers, lies in South Korea. In total, the size of the peninsula is similar to the state of Minnesota in the United States. (Coincidentally, the 38th parallel runs through the Oval at the Ohio State University!)

Though most of the islands within South Korean borders are close to the peninsula’s western coast, two islands sit further away. The largest is Jeju Island, which is covers around 1,833 square kilometers and was created by volcanic activity long ago. Thus, it not only boasts a soil composition of sedimentary and volcanic rock, but also one of Korea’s most famous volcanoes, called Mount Halla (introduced below). This island is a favorite tourist spot for travelers from throughout Asia, who flock there for its warmer weather, windswept fields, and rocky shores, as well as for a glimpse of its wild horses, carved rock statues, and a orange-like citrus fruit called hallabong.

The other major island is Ulleung Island (Ulleungdo), about 120 kilometers (75 miles) east of the Korean peninsula. Like Jeju Island, Ulleung Island is a small volcanic island that serves as a popular tourist destination. In addition to hiking, fishing, and whale-watching, visitors to this mountainous island may ascend cliffs to get a view of the Liancourt Rocks (Dokdo in Korean and Takeshima in Japanese)—a group of islets contested by both South Korea and Japan.

Mountains are THE significant geographical feature of the Korean peninsula. There are very few lowlands and those that exist tend to be the sites of major cities today. There are also no major lakes, due in part to a lack of glacial activity. The highest mountain on the Korean peninsula is Mount Paektu (Baekdu) or “White Head Mountain” (in China it is called Changbaishan, which means “Forever White Mountain”). Housing the scenic Lake Cheonji in its crater, it is located on the border between North Korea and China where it straddles the border between the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in the eastern part of China’s Jilin Province and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea). In the mid-1990s North Korean archaeologists claimed to have discovered the bones of Dangun, the legendary founder of the Korean people, near this extinct volcano.

Mount Paektu (Baekdu) is regarded as a sacred place by Koreans and plays a central role in the creation lore of the Korean people, which still plays a role in the politics of North and South Korea today. Its uppermost peak is 2,744 meters above sea level and the mountain summit is generally capped by snow from October to June. The high peak of Mount Paektu was formed by several volcanic eruptions, the most recent of which occurred in 1702. Following that eruption, more than 50 kilometers of the forest were destroyed by fire. Today, carbonized wood buried in the volcanic ash around the mountain can still be found. The area around the mountain is rich in natural resources, with more than 2,700 species of plants. In 1980 Mount Paektu became an international natural conservation base as part of UNESCO’s “World Network of Biosphere Reserves.”

At noted above, situated within the caldera of Mt. Paektu is Lake Cheonji (or Tianchi, meaning “Heavenly Pool” in Chinese). Sitting at an altitude of 2,189 meters, Lake Cheonji is the highest volcanic lake in the world. It covers an area of 9.82 square kilometers, with a north-south length of 4.85 kilometers and an east-west length of 3.35 kilometers. The average depth of this crater lake is 213 meters, and its maximum depth is 384 meters.

Sixteen peaks surround the crater of Lake Cheonji. A stream flows between a gap in the northern Tianwen and Longmen Peaks, forming the very short Chengcuo River. After flowing for approximately 1,250 meters, the stream gushes out from the mountaintop and forms a waterfall 68 meters high. A huge stone is situated at the edge of the falls, cutting the water into two main steams. These two streams crash into the deep valley below, forming the source of the Songhua River. The Chinese side of Mt. Paektu is a popular tourist destination, particularly among tourists from South Korea.

Other important mountains include the Nagnim Range in north-central North Korea and the Gangnam Range between North Korea and China. One of the most famous mountains is Geumgangsan or “Diamond Mountain” (1,638 meters) which is located just north of the DMZ in the Taebaek Range which runs along the peninsula’s east coast. Volcanic Mount Halla at 1,950 meters in height is located on the peninsula’s largest island, Jeju Island and is a popular South Korean tourist destination. Records from the Goryeo dynasty (918-1392 CE) indicate that this volcano may have been active within the last thousand years.

Major rivers include the Amnok (Yalu) River, which runs 790 kilometers long along the North Korean and Chinese border and the Tumen River, which flows west and east, respectively, in North Korea. Both of these rivers, which meet at Mount Paektu, comprise the border between North Korea and China. Other rivers include the Taedong River which flows through Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea; the Han River which flows westwards through Seoul, the capital of South Korea, and the 521-kilometer Nakdong, which is the longest river in South Korea.

|

|

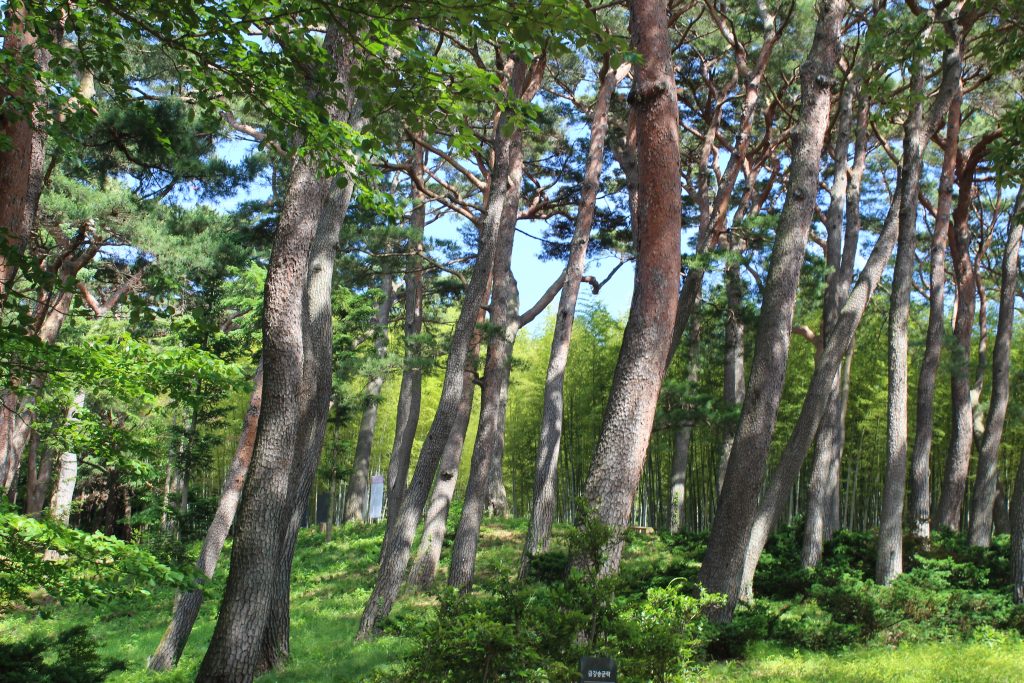

Bamboo (left) and red pine (right) at Ahopsan Forest, a pristine 400-year-old forest outside Busan, South Korea. |

|

Pine and deciduous forests once covered the Korean peninsula, though heavy logging in the early twentieth century and warfare in the 1950s caused deforestation and erosion. Reforestation projects (including a “green belt” around Seoul) are part of successful conservation efforts instituted since the 1980s. The DMZ zone is heavily armed on each side while, interestingly, over the years the “no man’s land” within this zone has become a refuge for a variety of wildlife, including the last Siberian tigers on the Korean peninsula, wild Amur leopards, Asiatic black bears, and red-crowned cranes. Other animals found on the peninsula include the Korean roe deer, Korean pheasant, Eurasian red squirrel, hare, and Asiatic magpie.

The climate varies significantly between the southern and northern parts of the Korean peninsula. Typically, there is a four-season annual cycle, though summers are shorter in the northern areas. While warm currents and winds (including typhoons) from the Pacific give the southern extremes a humid, almost tropical feel in summer, Siberian winds bring heavy snow and sub-freezing temperatures to the northern areas in winter. Average daily high and low temperatures for Pyongyang in North Korea range from about -3 degrees to -13 degrees Centigrade in January. Temperatures in Seoul range from -5 degrees Centigrade in the winter to 25 degrees Centigrade in the summer. The peninsula is ravaged by fewer typhoons than coastal Japan or China. Rainfall is usually more than adequate.

Geography of Japan

Japan is an island nation with one of the most unique geographies on earth. According to a recent count performed in 2023, it includes approximately 14,000 islands. There are four major ones: Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku. The islands of Japan lie in several arcs off the eastern coast of the Asian landmass on the convergence point of two tectonic plates. The line between these plates divides the major island of Honshu approximately in half on a north to south axis, creating a “northeast” and “southwest” divide. Thus, Japan has been described as an arc/trench system on a mobile belt—in other words, the islands are essentially mountaintops between deep ocean trenches in an area of unstable geographic conditions. Another way of geographically dividing Japan is between the Pacific side of the main islands and the side bordering the Japan Sea (what Koreans call the East Sea).

Cultural differences between the east (the Kanto region) and the west (the Kansai region) of Honshu date to the earliest times. Political and cultural dynamics between the two regions—which are to an extent geographically determined—are a prominent theme in Japanese history with bases of power shifting between the regions at different times in history. The Kanto region centers on the Kanto plain, the site of the present capital Tokyo, which is also Japan’s largest city. The early capitals Nara and Kyoto, in contrast, were in the Kansai region, another area of relatively flat land in the west.

In terms of latitude, Japan lies in the Temperate Zone, though there are seasonal and local fluctuations in weather that bring snows up to three meters deep and sultry summers that feel tropical. Rainfall in Japan is near the highest levels on earth and accounts to some extent for the rapid replacement rate of the forest vegetation that still covers two-thirds of the islands. The monsoon pattern includes rainy seasons in both spring and fall (there are a variety of terms in Japanese for the different kinds of rains). The vegetation profile of Japan can be divided into three regions: coniferous forests, cool temperate broad-leafed deciduous forests, and warm temperate evergreen broad-leafed forests. Despite this variety, Japan has no permafrost areas, no glaciers, and no deserts—features that are prominent in many other parts of the world.

Earthquakes and volcanoes are outstanding aspects of Japan’s geology. There are about sixty active volcanoes in Japan (close to one-tenth of the world total), including Sakurajima (Cherry Blossom) Island. Located near the large southern island of Kyushu, this volcano often spills dust on nearby urban areas. One offshoot of Japan’s unstable geography is the wide prevalence of hot springs throughout the country, a feature that has been incorporated into Japanese culture. Today, many Japanese spend vacations visiting hot springs and natural spas.

Japan has several freshwater lakes in Honshu and Hokkaido. The largest is Lake Biwa (shaped like a pear-shaped lute called biwa in Japanese and pipa in Chinese). Lake Biwa is situated roughly between the cities of Kyoto and Nagoya in central Honshu. The body of water lying between Honshu and the island of Shikoku is called the Inland Sea, though it is not actually surrounded by land.

|

|

| Lake Biwa (left) is shaped like an upside-down biwa lute (right), which is used to recite the Tale of Heike. | |

Among the animals of Japan are red-crowned cranes, whooper swans, sea eagles, sika deer, red foxes, raccoon-dogs (tanuki), serow, and snow monkeys. In some places the snow monkeys have learned to soak in natural hot springs, passing the knowledge to succeeding generations. In recent years, the populations of brown bears (Ursus arctos) in the Shiretoko National Park on Hokkaido Island and Asian black bears in remote parts of Honshu have exploded, resulting in an unprecedented number of bear-human incidents that have included bear attacks on elderly people in these low-populated rural areas.

CULTURAL CONTINUITIES

Overview

The cultures of East Asia have a long experience of interaction dating back to the earliest times. In some eras, relations have been very positive, with a great deal of cultural borrowing and mutual influence. At other times, however, relations have been minimal, and in some cases, various countries in the region have been at war. There has been sharing between the cultures of the region, yet great differences—at least as great as those between European cultures—exist between the cultures of East Asia.

This said there are certain bedrock attributes that tie East Asian cultures together as a region. Among these are aspects of premodern technology; certain agricultural practices; elements of traditional worldview (influenced by Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism, and nature-based beliefs); a stress on family, groups, social roles and hierarchy; recognition of the values of education, work, and self-cultivation; and many common historical experiences both among these cultures and with outsiders to the region. The following is a brief overview of some of the major cultural continuities in East Asia over the course of hundreds and even thousands of years of interaction. Many of the things listed will be explored in greater depth in other modules. Continuities in very recent times will be dealt with elsewhere in the course.

Early Technology and Culture

Ceramic technology was advanced very early in East Asia and became important in international trade. Bronze casting goes back thousands of years in this part of the world and was used for ritual vessels, weapons, and tools. At times, architectural patterns, include the design of housing, temples, and even entire cities spread across the region in waves. Paper was invented in China and spread to nearby areas, and finally to other parts of the world. Certain innovations in cloth production were also widespread in the region, including the production of silk, hemp, and cotton, as well as the use of certain dyes, like indigo.

|

|

|

|

Agriculture

Wet-rice agriculture, sericulture (the cultivation of silkworms) and tea culture began early and spread far and wide in the region. Rice agriculture dates from 5,000 BCE in China (and possibly originated in South East Asia). It entered Korea by 700 BCE, and Japan by 300 BCE.

Rice agriculture is intensive and demands group cooperation. Self-sufficiency in rice production is still an important aspect of national identity in the region. Even in urban areas, the legacy of rice cultivation and other intensive farming practices have left an imprint on social personality in East Asia. The cultivation process involves a high degree of cooperation and conformity to roles in order to succeed. Over time intensive agricultural practices became one of the cohesive elements that form the building blocks of major social traditions in East Asia. More aspects of some these technologies and social traditions will be explored in later modules.

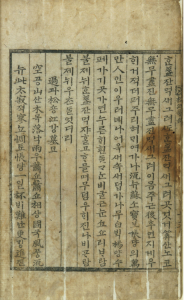

Chinese-influenced Writing Systems

Writing originated in China c.1800 BCE. Chinese writing was later adopted and adapted by the Koreans and Japanese, who later created their own writing systems in some ways inspired by Chinese writing. Much more on these writing systems is introduced in Module 6.

Self-cultivation, Education, and Hard Work

All of the major cultures in East Asia place a very high value on self-cultivation, education, and hard work. This is at least in part a legacy of Confucianism, which is examined in Module 3. Many believe that one reason much of East Asia is so economically competitive today can be traced back to the traditional Confucian idea that education, personal cultivation, and hard work translate into success—which is defined in terms of individual, family, and group accomplishment. See the essay in Module 5 for a look into a day in the lives of students in East Asia.

Neo-Confucian Heritage

Although it is problematic to generalize across the very complex and different cultures of China, Korea and Japan, they may be seen to share certain aspects of social personality. For example, in all these societies individuals share a strong tendency to affiliate themselves with groups, such as family, school, company, area of origin, nation, etc. There is also an understanding and respect for social hierarchies and roles within those hierarchies.

Behavior in these cultures may therefore be seen as highly “context sensitive.” That is, there are high expectations for specific, usually clearly defined, behavior in recognized social roles. For example, there are strong expectations for how students and teachers should behave and be treated in and out of class, given their different roles in society. This also explains why name cards are so important in business relations: it is necessary to know a person’s rank and role in order to know how to properly speak to that person (in other words, to be able to perform one’s own role). If a person does not conform to expectations, there will be social consequences. Clearly, the idea that individuals in various societies perform prescribed roles in different contexts is universal, but it may be argued that the degree to which these roles and behaviors are prescribed and the degree to which individuals follow these prescriptions may vary culturally.

The idea of “face” also has equivalents across Chinese, Japanese and Korean cultures. Face depends in large part on what an individual feels the group feels about them. Simply put, the idea is that if an individual believes they have not met certain group expectations (which could mean a whole range of behaviors), that individual may feel a “loss” of face has occurred and that culturally appropriate actions must be taken to regain or “save” face.

All three cultures also have concepts related to a dichotomy between what the Japanese call tatemae and honne. Tatemae refers to the “surface” that a person presents to society—a “self” that is presented to ensure smooth social relations and to navigate the intricacies of social interactions. Honne, on the other hand, is the “inner self”—what one really thinks and feels. This inner self may be similar or different from what is displayed in the tatemae or surface mode. Many works of East Asian literature, for example, make use of disparities between what is thought and what is actually spoken or revealed. Again, these orientations have also been linked to factors such as the legacies of intensive agriculture and of Confucianism, both of which often taught and rewarded people for conforming to group expectations for the benefit of the greater good. More insights into social personality will also be gained in subsequent course modules.

Elements of Worldview

Confucianism, Daoism (Taoism), nature-based beliefs, Buddhism, and other belief systems have all contributed to the various worldviews held by people in East Asia. Unlike in many parts of the world, differing beliefs have often coexisted in relative peace in these cultures over many centuries and in many cases, elements of different belief systems are acknowledged to complement each other in individuals’ lives. In the last two hundred years world view in East Asia has also been profoundly influenced by interaction with the other parts of the world, especially Western cultures, as well as waves of new technologies, and, most recently, rapid and unprecedented globalization. See Module 3 for a deeper look.

ETHNIC DIVERSITY

Overview

With a population surpassing 1.4 billion people, China is the most populous nation on earth. Add to this a history of nearly 5,000 years during which borders expanded and contracted many times, along with massive migrations between points in the vast region, and the cultural diversity of China is inevitably both vast and complex. Although ethnic diversity is not always apparent to many non-Chinese visitors who limit their stays to Shanghai, Shenzhen, or Beijing, any trip between geographical regions, and especially to the border areas, will give a much broader picture. Despite the leveling forces of modernization, there are dozens (even hundreds by some estimates) of ethnic groups in China, making China by far the most diverse country in East Asia.

By comparison, Korea and Japan have quite uniform populations ethnically. Korea has regional diversity roughly paralleling the areas of the old Three Kingdoms (introduced in Module 2) and has historically included small Chinese communities as well. There is also a community of people indigenous to Jeju Island, called Jejuans or Jeju-saram, who are regarded as an ethnic minority, with their own language and traditional customs. Japan also has regional diversity among the majority ethnic group, especially between the western areas around Tokyo (the Kanto Plain area) and the eastern region around Nara and Osaka (the Kansai area). The southern islands making up Okinawa also have distinct local cultures. The best-known ethnic minority in Japan, however, are the Ainu (introduced below), although there are also large ethnic Korean communities in Japan that go back many generations. Another group in Japan is a class of occupational minorities known as burakumin, who were traditionally involved in stigmatized trades such as tanning and leatherworking.

Ethnicity in the People’s Republic of China is understood in terms of a group’s common history, language, area of inhabitation, customs, and livelihood (criteria borrowed from the former Soviet Union). Since 1949, the Chinese government has created two large categories by which to classify people on the basis of ethnicity. These categories are both based on the idea that China is a conglomerate of “ethnic groups” (minzu in Standard Chinese). While all natives of China are citizens, these citizens all belong to different “ethnic groups.” According to the constitution of the People’s Republic of China all citizens are equal under the law. Furthermore, any person on earth of Chinese heritage is believed to be part of the Zhonghua minzu, or “Chinese people.”

The two major ethnic categories in China are: the Han ethnic group (Hanzu, or “Han nationality”), whose members make up over 91 percent of the population. The second category is comprised of 55 ethnic minority groups (or shaoshu minzu), whose members comprise over about 8 percent of the population. Thus, China should be regarded as a culturally and ethnically diverse nation, made of many local cultures, rather than as is often assumed by both non-Chinese and Chinese themselves as a cultural monolith.

The Han Ethnic Group of China

The Han ethnic group takes its name from the ancient Han dynasty (206 BCE- 400 CE). In the course of its history, the dynasty absorbed as many as 2,000 local ethnic groups, and many local differences still exist among the Han people. Linguists and anthropologists recognize a number of major subgroups or local cultures among the Han today, noting especially the differences between North and South China, the Yangzi River being a convenient dividing line between the areas. The geographical situation examined elsewhere in this module has helped shape the ethnicity of areas throughout China, as have the many migrations on the Asian landmass that date from far back in prehistory.

Among the Han subgroups (which are not recognized in official census data), are speakers of northern and southwestern Mandarin. These people inhabit much of north, northeast, and northwest of China, and parts of the southwest, including Sichuan and Yunnan provinces. Southeast China, from the Yangzi delta southwards, is the area of the most pronounced diversity among the Han. Groups, often associated with ancient regional kingdoms, include the Wu in the Yangzi delta, the Cantonese (or Yue) of Guangdong and eastern Guangxi, the Xiang, Gan, and Min peoples of Hunan, Jiangxi, and Fujian (and Taiwan), respectively, and a group known as the Hakka (or Kejia), who have historically lived in scattered settlements in southern China and Southeast Asia.

As one can gather, one striking difference between these subgroups is language. Differences between the local dialects (or what the Sinologist Victor Mair has called “topolects”) of Chinese are so great that they are often mutually unintelligible. Even those dialects that are quite similar may present problems for non-native speakers, especially in terms of idioms and pronunciation. Even though Standard Chinese is taught in schools throughout the country, local variations of the standard have developed due in part to the influence of local dialects.

Other differences include daily life customs; food; kinship systems; marriage and funeral rituals; banquet rules; religious expression; and folk ideas about what it means to be (or not to be) part of a certain group. While many of these differences have been at least partially eroded or submerged during recent decades of rapid social change, it does not take long for visitors to note local differences. As explored in Module 5, food—and when, and by whom it is consumed—constitutes a pronounced marker of regional difference among the local Han Chinese cultures as well as the ethnic minorities.

The Ethnic Minorities of China

|

|

| Many images of ethnic minority women have appeared in the media since 1949. Above, Third Sister Liu, a legendary heroine of the Zhuang ethnic group has been the subject of movies and musicals since the 1960s. Known as a “song goddess,” legends tell of her using folksongs to “duel” with evil landlords centuries ago. Film-maker Zhang Yimou created a splendid water show of the story in Guilin, China. | |

As noted above, besides the Han, the other major category into which Chinese citizens are categorized is that of “ethnic minorities” or “minority nationalities.” It is interesting that until recently the term “ethnic group” was translated as “nationalities,” as if the groups were nations within a nation. It may be that the term was officially abandoned (though it does still occur in some popular writings) because “nationalities” had too strong a political flavor. Recently, many government publications simply use “minzu” without the translation into “minority nationalities” or ethnic groups.” Thus, for instance, a university that was once called Southwest University for Nationalities is now called Southwest Minzu University.

Prior to 1949, successive Chinese governments dealt with ethnic differences in various ways developed under different historical circumstances. During times when the Han Chinese were in power, it was assumed by the rulers that most peoples within and without China’s borders sought to emulate or assimilate to the “superior” Han Chinese culture. Access to the fruits of Chinese culture was often done via tribute agreements. The Chinese sometimes used such agreements in attempts to pacify potential invaders on their borders—though this did not always succeed. It was not unusual for exchanges of brides to be part of such agreements between leaders.

Images of forced marriage to regional overlords or powerful landowners are part of the folk literature of some ethnic groups in southwest China. For instance, the legendary Anyo of the Nuosu people (a sub-group of the Yi ethnic group) in Sichuan province was captured by an overlord in the Ming dynasty. Refusing to give in to his depredations, she bit off her finger to send to her parents, then hung herself in a dungeon. The accompanying picture is from a translation of her oral tale from Yi language into Chinese, reflecting the aesthetics of representation of ethnic minority women in the late 1990s.

Ashima, a legendary rural young woman of the Sani people (a sub-group of the Yi), has been the subject of films and tourist performances since the 1960s. She is said to have played her mouth harp to help her brother rescue her from an evil landlord. Later, she died in a flood on the way home. Her spirit is said to live in a cave in the Stone Forest, Yunnan province. An English version of her ballad was published in the early 1960s. Her representation below reflects the emphasis on images of plain, hardworking rural women as promoted in social agendas of the 1950s.

During the eras of Mongol and Manchu rule (detailed in Module 2), certain ethnic boundaries were rigorously enforced by the invaders as they took over as leaders of the country, and Han Chinese were often denied access to certain social privileges while persons of other groups were given high government positions. During the Ming and Qing dynasties ethnic differences led to continual uprisings among certain ethnic groups in northwest and southwest China and ethnic tensions contributed to the rise of the Taiping rebels in the 1850s in southern China. In the early 20th century, the young Republic of China recognized only five ethnic groups: Han, Manchu, Mongol, Hui, and Uygur—which were represented as five yellow stars on the red flag of the People’s Republic of China when it was established in 1949. Many other groups have been officially recognized since then and the meaning of the stars has since been given other explanations.

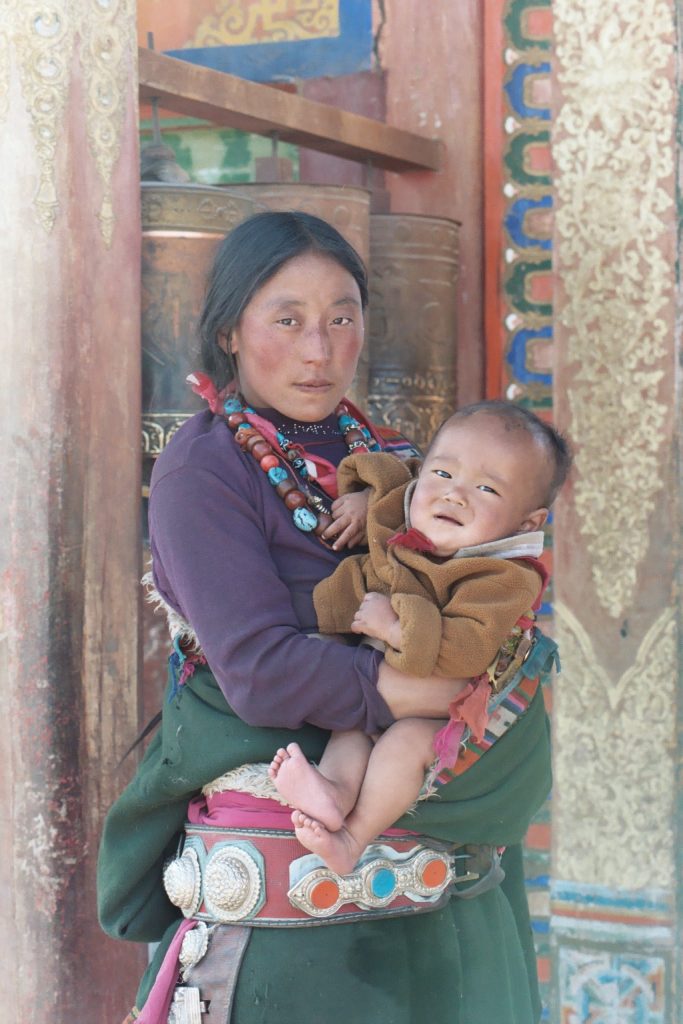

The 55 recognized ethnic minorities range in size from groups in the many millions to those with only a few thousand members. Most ethnic minority peoples live in China’s extensive border lands, which range from the grassy steppes, deserts, and forests of the north to the mountain fastnesses of south and southwest China. Herding, upland agriculture, handicrafts, and more recently, ethnic tourism are mainstays of these various local economies. Presently, the largest group are rice agriculturalists called the Zhuang (Chuang), who number over 15 million and live mostly in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region bordering Vietnam. Other large groups include the Yi, Miao, and Dai also of the southwest, and the Uygurs, Tibetans, and Mongols of the north and west. In recent years, the number of people acknowledging Manchu ancestry has risen to over 10 million, due in part to perceived advantages in ethnic minority status as well as group pride. Among the medium-sized ethnic groups, numbering from a few hundred thousand to over a million people, are the Yao, Dong (Gaem), Jingpo, Bai, Naxi, and Tujia of southwest China, and the Tu, Salar, Kazakhs, and Hui of northwest China. Smaller nationalities include the Daur, Olunchun, Evenki, and Hezhen of the forests of northeast China, and the Jino, Bulang, Wa, Jingpo, and Molao peoples of the southwest. Yunnan province alone has approximately 28 different ethnic minorities. The ethnic minority groups in Taiwan are classified under one general term in the PRC classification system, but greater diversity is recognized locally. Donning traditional clothing is a way to make a range of social statements.

|

|

|

|

| Images of various ethnic costume: Bai women in traditional dress, Dali, Yunnan (upper left); Uygur shoppers at the market, Hotan, Xinjiang (upper right); young Qiang women in traditional garb with embroidered flowers, Sichuan, China (bottom left); and Tibetan woman and child, Tibet, China (bottom right). | |

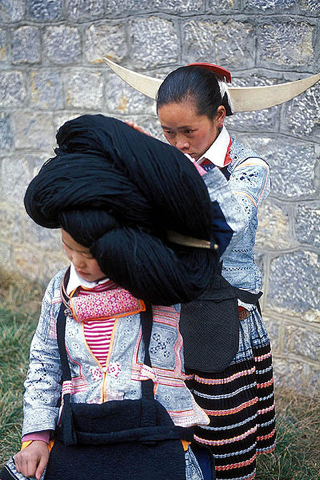

As noted, many of the larger ethnic minority groups have many subgroups. These subgroups all go by different names, and in some instances like the Miao and Yi, none of the groups call themselves by those names when speaking in their own language dialects. For instance, although there are over 9 million Yi, there are around 70 subgroups with self-appellations (what anthropologists call “ethnonyms”) such as Nuosu, Lipo, Lolopo, Nisupo, and Sani. Aside from different names for themselves, these subgroups differ from each other in traditional clothing styles (especially of the women), local customs, folklore, and language dialect. A similar situation exists among divisions of the Miao ethnic group, which has subgroups with names such as Hmong, Hmao, Gho Xiong, and Hmu.

Women in different Miao subgroups, “Longhorn” hairstyle in western Guizhou, and silver ornaments in SE Guizhou, China.

Nuosu (a subgroup of Yi) women welcoming guests in Puti Village, Sichuan (above), and Sani (Yi subgroup) young women in festival garb, Stone Forest, Yunnan (below).

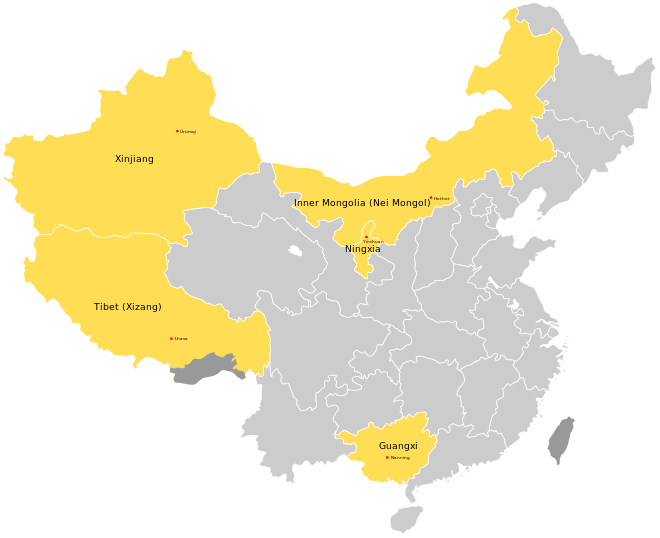

Political Entities and Special Considerations

Most ethnic minority peoples in China live in specially designated “autonomous areas,” which range in size from townships and counties to prefectures and, largest of all, five province-size “autonomous regions.” In most of these areas, minority representation at all levels of local government is prominent, although Han people may actually be the majority in a given area (such as Inner Mongolia). The regions are called “autonomous” because historically certain government policies have been modified to account for local conditions and customs—a philosophy which has been followed or ignored to various degrees over the last 70-plus years depending on central government policies and leadership.

The five large autonomous regions are: Xizang Tibetan Autonomous Region, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, and the smallest, the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (located in northwest China). Yunnan, Guizhou, Hunan, Sichuan, Gansu, and Heilongjiang are all provinces with a number of minority areas. Aside from the largely rural populations in the autonomous areas, many minority people live in urban areas all over China and fully participate in modern urban life.

Promise and Problems

Since the end of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1970s, there has been general improvement in the implementation of minority policies related to the balanced treatment and increased participation of minority peoples in China, though ethnic tensions simmer in some regions in the west. For instance, over the last decade, controversial “anti-terrorism” measures have been undertaken in Xinjiang.

Many ethnic minority areas have shown economic advances, especially in areas where locals have taken advantage of more relaxed economic policies, where infrastructure has been dramatically improved, and where tourism has been successfully encouraged. The recent poverty elimination campaign specifically targeted minority areas such as the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Region in southern Sichuan, and Tibetan areas in Qinghai and Gansu provinces. The number of young minority men and women entering professions outside those traditionally followed in their communities is rising and members of all 55 ethnic minority groups are now represented at the Central Minzu University in Beijing, the largest of several institutes of higher learning that give preference to minority applicants.

In many ethnic minority areas of China, clashes between the needs of a rising superpower and the environment are on the rise. Desertification, water and air pollution created by local industries, mining, deforestation, overgrazing, and the poaching of endangered species are all current issues with far-reaching consequences. These problems confront not only the local ethnic minority people, but all people in the rural areas of China as a whole. A vast network of high-speed rail and greater connectedness to more mainstream culture through technology, as well as logging, mining, fencing of grasslands, and the damming of rivers are situations that are affecting traditional local cultures in various ways.

Information on several Chinese ethnic minority cultures will be presented in later modules.

The Ainu of Japan

The Ainu are a native people of Japan that are distinct from the majority population of the country. Until the early twentieth century, the Ainu followed a lifestyle that combined hunting and gathering with agriculture. Over the centuries most of their traditional land holdings and much of their culture has been displaced by the majority Japanese ethnic group. Most Ainu today live in a few areas on the northern island of Hokkaido, although others live on the Kurile and Sahkalin islands to the north. Written records on Ainu history before the 14th century are sparse. They may be descendants of the original peoples of Japan, though how they are linked to cultural patterns of the earlier periods is still being investigated by archeologists.

The Ainu lifestyle was based on the natural resources available in the northern temperate forests, river valleys, and seacoasts. Mammals and fish, including deer, bear, raccoon-dogs, salmon, trout, and smaller freshwater fish, were captured in the forests and river valleys. Seals and large fish like tuna were harvested along the coasts and on the seas. Poison arrows were among the Ainu hunting tools. Wild plants in the Ainu diet included a type of wild lily, the bulbs of which were a source of starch. Garden plots were kept near the valley settlements. Foxtail millet, Chinese millet, pumpkins, garlic, leeks, and potatoes (introduced in the late 18th century) were among the cultivated crops. Due to beliefs related to nature spirits (kamuy or kamui), gardens were never weeded, and two halves of a shell were used to harvest grain so as not to kill the plant. A digging stick was the main gardening tool.

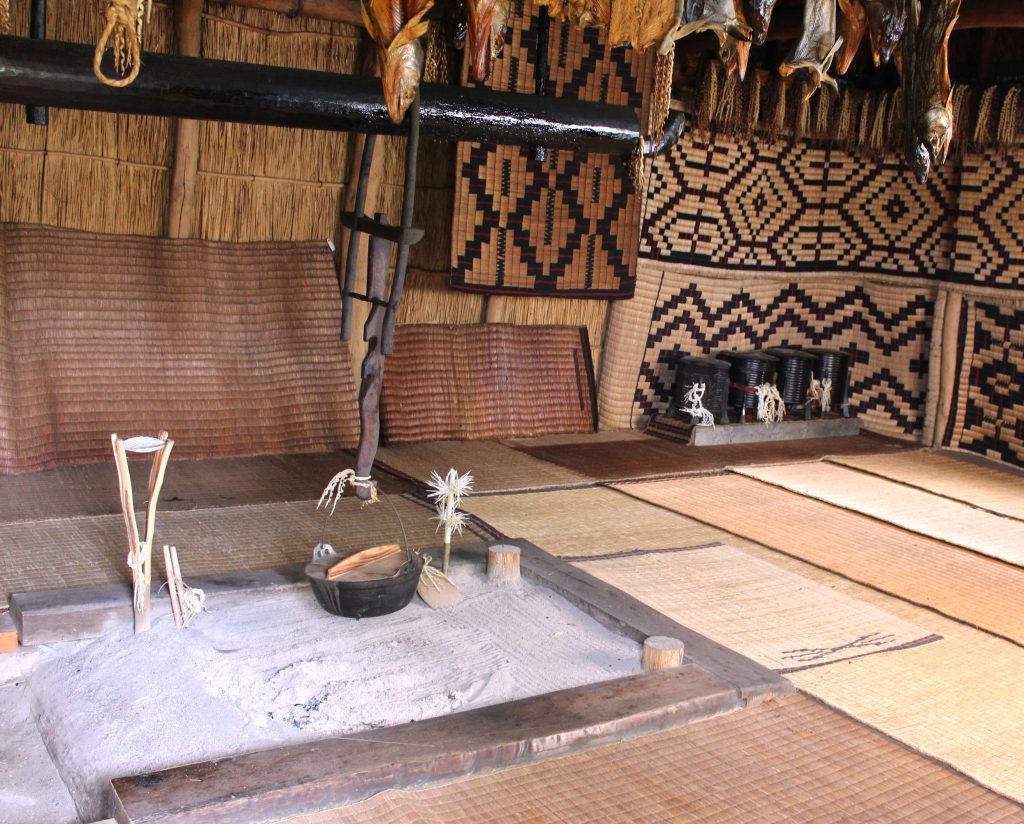

Villages were small settlements situated near protective hills and fresh water. Houses were made of wood and included a long fire pit in the middle of the home structure where people gathered to eat and socialize. On special occasions, epic poems about the exploits of the nature spirits were performed, with audience members tapping sticks on the timbers of the fire pit in time to the rhythm. A very important ceremony was a ritual in which the spirit of a bear was placated. The Ainu believed that it was necessary to maintain harmony with the nature spirits, as they were the source of many natural resource

Today, the Ainu people officially number around 25,000, though unofficial accounts suggest the population could be greater. Since the 1970s a cultural revival has taken place. Ainu have become more educated and vocal about their rights and about social justice issues. Efforts are being made to preserve their traditional oral and material culture as well as to promote indigenous rights. These efforts include political and legal activism, websites, gatherings, and local Ainu cultural museums that feature traditional dwellings, handicrafts, recordings and demonstrations of folk dances, myths and stories, and art. A well-known “living museum” where the general public can be introduced to traditional Ainu culture is located in Shiraoi, a short train-ride from Sapporo on Hokkaido Island.

Upopoy and HMNP: Representing the Ainu in Museums in Hokkaido

Upopoy National Ainu Museum

In June 2024, Prof. Mark Bender visited Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples (HMNP), two of the outstanding museums that represent Ainu and related Northern peoples to the world. Upopoy, named after a style of Ainu folk song, is located in the small town of Shiraoi, about an hour train ride from Hokkaido’s capital, Sapporo. The site consists of a large modern museum, a special performance hall, and a section of traditional thatch roof buildings – all on the shore of a small lake.

Since Bender’s first visit twenty years ago, the museum site has been expanded and upgraded. Today, guests can witness both live and digital performances of Ainu folk dances and songs, traditional crafts, and special visits to the thatched farmsteads that feature rectangular hearths (used for cooking and recitals of epic poetry) and drying racks for fish and game.

|

|

Traditional Ainu houses were framed with local woods, thatched with water reeds. The main room held a central fireplace where family and guests interacted. At special events, singers would relate epics about supernatural beings and heroes. Other parts of the room included display and storage areas for family treasures and household essentials and spots for activities such as weaving. |

|

Exhibits in the huge museum feature displays of traditional Ainu, clothing and related weaving tools, religious items that include intricately carved slats of wood (tukipasuy), ceremonial carved and lacquered wooden bowls (tuki), and shaved wooden sticks (inau) used in ritual offerings of drink and food to various kamuy (nature spirits). Numerous items relate to the annual bear rituals (iyomante), and most of the homesteads in the traditional village have a raised pen once used to keep young bears. One exhibit in the museum hall is an elaborately decorated model bear tethered to a tall wooden post, as in the sacrificial rituals.

[Click images to zoom] |

|

|

Other parts of the exhibits and village displays include traditional clothing of woven barks and grasses, woven reed mats, dugout log boats, hunting instruments, children’s games, and women’s tools for a variety of tasks including food preparation and weaving looms using strings and stones in a wooden frame which follow ancient patterns of construction.

There is also a wing of exhibits that chronicle Ainu achievements of survivance in recent decades, following a difficult century of assimilation and cultural change brought on by the development of Hokkaido since the latter 19th century.

Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples (HMNP)

The Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples (HMNP), dating from 1991, is located near the small port city of Abashiri (also known for its former prison complex), on the northern coast of Hokkaido on the Sea of Okhotsk, which is one of the few places in that latitude on earth with free-forming sea ice.

The museum, houses collections of artifacts of peoples from northern areas ranging from the Sami people areas in Scandinavia, across Siberian Russia, and on in to North America and Greenland. The Ainu and related peoples of the Sea of Okhotsk area are the southernmost part of this grouping of northern peoples.

The origins of the Ainu are still not fully solved, but the museum offers archeological exhibits of early Jomon and Okhotsk cultures on Hokkaido and points out possible relations over time with populations on nearby islands, mainland Northeast Asia, and other parts of Japan as part of the origins puzzle. It also has exhibits of many articles of Ainu material culture in direct comparison with those of other Northern peoples, including groups such as the Nanai/Hezhen of rivers dividing China and Russia.

The museum is within walking distance of the Museum of Ice, which vividly displays the winter challenges to any peoples living in the seasonally cold environments. Another nearby attraction is the Shiretoko National Park where deer and brown bear once integral to Ainu life are protected from development.

DEMOGRAPHY

DEMOGRAPHY OF CHINA

|

Country name: |

Conventional long form: People’s Republic of China |

|

Conventional short form: China |

|

|

Local long form: Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo |

|

|

Local short form: Zhongguo |

|

|

Abbreviation: PRC |

|

|

Population: |

1,413,142,846 (2023 est.) |

|

Age structure: |

0-14 years: 16.48% (male 124,166,174/female 108,729,429) |

|

15-64 years: 69.4% (male 504,637,819/female 476,146,909) |

|

|

65 years and over: 14.11% (male 92,426,805/female 107,035,710) (2023 est.) |

|

|

Population growth rate: |

0.18% (2023 est.) |

|

Sex ratio: |

at birth: 1.09 male(s)/female |

|

under 15 years: 1.14 male(s)/female |

|

|

15-64 years: 1.06 male(s)/female |

|

|

65 years and over: 0.86 male(s)/female |

|

|

total population: 1.04 male(s)/female (2023 est.) |

|

|

Infant mortality rate: |

total: 6.49 deaths/1,000 live births (2023 est.) |

|

Life expectancy at birth: |

total population: 78.23 years |

|

male: 75.5 years |

|

|

female: 81.2 years (2023 est.) |

|

|

Government type: |

One-Party Communist state |

|

Capital: |

Beijing |

|

Administrative divisions: |

23 provinces (sheng, singular and plural), 5 autonomous regions (zizhiqu, singular and plural), and 4 municipalities (shi, singular and plural) |

|

Provinces: Anhui, Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guizhou, Hainan, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Jilin, Liaoning, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Shandong, Shanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, Zhejiang |

|

|

Autonomous regions: Guangxi, Nei Mongol, Ningxia, Xinjiang, Xizang (Tibet) |

|

|

Municipalities: Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, Tianjin |

|

|

note: China considers Taiwan its 23rd province. See below for facts on Taiwan |

|

|

Legal system: |