4 Module 3: East Asian World Views

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

Introduction

Every culture has its own worldview, or way of making sense out of being and existence. In the West major religions stress the idea of one supreme being and beliefs in that being to the exclusion of all other religious beliefs. Although there are many adherents to such religions as Christianity and Islam in parts of East Asia, worldview in regards to belief is very often more inclusive than exclusive. In East Asia one often finds views that are both eclectic and syncretic in nature. That is, a person may draw on and combine aspects of a number of belief systems in order to deal with the situation of existence. Rather than using the term “religion” the concept of the “Three Teachings” is widely understood in East Asia. These three teachings are Daoism (Taoism), Confucianism, and Buddhism. The first two developed in ancient China and spread to other parts of East Asia and parts of Southeast Asia, while the third one, Buddhism, originated in India. The Three Teachings have both formal and popular aspects. The formal sides include temples and monasteries, hierarchies of clergy and monks, and canons of written scriptures. In many cases such institutions received the support of reigning governments. On the popular level local communities often combine aspects of the Three Teachings, sometimes with other beliefs like animism, shamanism, and ancestor reverence, described elsewhere in this module. Moreover, for many people in East Asia today these traditional beliefs are more of heritage than an active part of daily life. That said, many of the perspectives, concerns, and values in these traditional teachings have explicit or implicit influences on thinking and behavior. Thus, any discussion of beliefs in East Asia is a complicated one.

Local Belief Systems

The Heritage of Animism

One of the most pervasive beliefs still common in many parts of East Asia is what anthropologists call “animism,” or the belief in nature spirits. In the animist view, many objects and creatures such as unusual rocks, waterfalls, heavenly bodies, old trees, and sometimes animals are thought to be the abode of spirits. In some cases, spirits may even inhabit dwellings or be incarnate in special people. The best-known of these traditions are the Shinto beliefs of Japan that predate yet still co-exist with Buddhist traditions that arrived by the 6th century CE from the Asian mainland. Animistic beliefs and shamanism (discussed below), have ancient roots and many diverse expressions all over the globe. In many parts of East Asia today, especially in rural areas, close observers may find offerings of incense or wine left at small altars in front of ancient trees, or shrines built on mountainsides to house the local mountain spirit. Although some modern governments in the region have at times suppressed expressions of animism and shamanism as forms of “superstition,” many people in East Asia continue to acknowledge the beliefs in daily life, often alongside or integrated with, other belief systems.

Animistic Beliefs of the Miao (Hmong) in China

The Miao (Hmong) ethnic group numbers over nine million people, most of whom live in mountainous areas. Rice is the most important crop, and many fields are located along river bottoms or on steep hillsides. In some areas, bamboo windmills are used to irrigate the hillside fields. One of the ancient beliefs of the Miao living in Southeast Guizhou province, China, concerns a female creator figure known as Butterfly Mother (Mai Bang). According to the myth, a lovely butterfly emerged from a sweet gum tree, then flew along a river. Foamy waves rose up and impregnated her. Finding refuge in mountain hollow, she laid twelve eggs. After many eons, the eggs hatched, and out popped the ancestors of tigers, dragons, humans, and many other things. Such myths are part of the oral tradition of the Miao people. During festivals, weddings, and house-raisings (when new houses are built) pairs of male and female singers will sing the myths in a sort of song competition, each pair singing a few lines and asking a question to the opposing pair about what comes next in the story. In this way, the ancient stories are recounted for new generations.

This passage from the epic tells how Butterfly Mother found her mate while flying along the river. Notice how the actions of people are reflected in the behavior of the butterfly and other things in nature, including the wave foam on the river. As noted such epics are sung as a kind of conversation between 2 pairs of singers (pair A and pair B).

A:

Some people are born at favorable times,

and can easily find a mate;

but Butterfly was born at an unlucky time,

so it was hard for her to find one.

With whom could she court?

B:

She courted with Wave Foam;

they played beside a clear water pool;

in a muddy pool, fish and shrimp frolicked.

Butterfly and Wave Foam courted,

and later became a couple.

For how many years was Butterfly married?

A:

She was married for twelve years,

and laid the Twelve Eggs.

Note:

(Lines from Butterfly Mother: Miao (Hmong) Creation Epics from Guizhou Province, China, translated by Mark Bender, 2006.)

Animistic Beliefs of the Ainu in Japan

The Ainu people are the indigenous people of Japan and until the early 20th century led a hunting, gathering, and horticultural lifestyle. Most Ainu today live on Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido. Traditional Ainu beliefs are strongly animistic. Spirits are thought to reside in all living things, as well as in rocks, mountains, waterfalls, and other “inanimate” phenomena of the natural world. Certain powerful spirits are regarded as divinities called kamui (similar to the kami in Japanese Shinto beliefs, but with some differences). One important idea is the inter-relationship between the world of spirits and the world of humans. Animals are thought to be kamui in disguise. They come to the human world in animal form (hayokpe) and are considered a gift of meat and hides. Hunters kill animals with this understanding in mind. Thus, when a deer or bear is killed, feasts are held to celebrate the gifts. A special seat is left vacant for the spirit to sit in and songs and dances are sung in its honor. Specially trimmed sticks (called inau) are also presented to the spirits as gifts to take back to the spirit world. It is hoped that the kamui divinities will make a good report and encourage other spirits to bring more meat and hides to the humans. Thus, a balance between humans and spirits of the natural world was maintained for centuries before natural resources began to be over-harvested in the late 19th century as a result of population inflow and the needs of an industrializing country. (Various aspects of Ainu song, dance, and culture are introduced in Module 1 and Module 2, Performance in East Asia.)

Animistic Beliefs in Korea

Many cultures in East Asia recognize the existence of spirits that live within the house. In the rural areas of South Korea, belief in house spirits (gashin) has a long tradition that is still followed in many places. When a traditional-style house is built, a special ceremony is held when the main roof beam is put in place. A piece of cloth is wrapped around the center of the beam, sometimes containing images of “Mr. and Mrs. Roof Beam Spirit.” These spirits contribute to the welfare and harmony of the household.

Other spirits populate the home as well. These include the courtyard spirit, the doorway spirit, the pickled vegetable crock spirits, the kitchen spirit, the well spirit, and even a toilet spirit (said to be quite ugly). Tiny pictures or images, including constellations of stars associated with a particular spirit, are sometimes placed near the objects where the spirits reside. In some homes, incense is regularly burned to gain favor of the spirits.

In some mountain areas, small piles of stones can be seen near temples, ancient trees, waterfalls, and other sacred places. A visitor may add a stone to a pile or tie a piece of colored cloth to a tree branch as an offering to the local spirit, such as the Mountain God.

The Heritage of Shamanism

Shamanism shares many features with animism and in some cases, it would be difficult to attempt to clearly distinguish between the two. The word “shaman” is derived from the Manchu (Manju) language of northeast China. The term literally means “one who knows” and refers to a shaman’s knowledge of the unseen supernatural world. The basic function of shamans is to directly communicate between the present world of humans and the unseen world of the spirits. Shamans often use percussion instruments such as drums or brass gongs to enter a trance state. Though practices vary widely, shamans are found in many cultures worldwide. An alternative term for shamans and similar traditional practitioners is “ritual specialists.”

A Shaman may invite a spirit into his/her body and act as its mouthpiece, communicating the spirit’s advice to human clients. In other cases shamans may enter trances in order to journey to spirit worlds in search of a client’s deceased relatives or escort the souls of the dead to the afterworld. In many cases, a shaman is recruited to the profession by a dream or a sickness that can only be cured by becoming a shaman. In their seances, shamans draw on deep psychological symbolism in their costumes and movements, employing repetitive rhythms, special dance movements, and dramatic actions to create situations that powerfully focus the audience on the proceedings. Some costumes of shamans in North Asia have metal deer antlers, heavy brass mirrors, brass bells, colorful streamers, and bird effigies that stress relations with animal and bird sprits and the powers of flight. Among the Manchu (Manzu), lengthy shaman rituals involving the entire clan were once held in times of natural disasters.

The traditional worldview of the shaman divides the cosmos into three planes: the upper spirit world, the human realm of earth, and the lower spirit realms. In shamanist cultures, practitioners find their way through life with the aid of various spirits that may be worshipped daily or at special times. While male shamans are still found in a few places in northeast China, many shamans (mudang) practice in South Korea, the majority of whom are women. Shamanism is quite popular in South Korea today, though engaging a shaman and holding an elaborate ceremony (called gut—pronounced like “coot” ) can be very expensive.

In recent years a small revival of shamanism has taken place in northeast China and Inner Mongolia after decades of government suppression. Forms of ritual activity that can be considered shamanism are also found throughout other parts of China, though these practices differ in many respects from northern styles. One example is the su-nyi and bimo, shamans and priests (respectively) among the Yi (Nuosu) people of Southern Sichuan Province of China. Many Daoist priests in Taiwan and other Chinese areas function in ways similar to shamans, especially in the conducting of seances and funeral rites. Traces of shamanism are still found in some rural Japanese communities today, where shamans were once part of Shinto practices.

The Heritage of Ancestor Reverence

Ancestor reverencing, sometimes called “ancestor worship,” is a common aspect of worldview in East Asia and has implicitly survived even in North Korea where religious expression is still strongly suppressed. Linked in many ways with the ethics of Confucianism, the practice is based on the idea that living people are a link between the realm of those yet born and the realm of those who once lived on earth, and are now part of the spirit world. The specific conceptions and practices vary between cultures and locales like other traditional beliefs in East Asia. In many cases, ritual offerings at home or clan altars honor deceased ancestors. In such cases, such as the O-bon festival of Japan, spirits of the dead are invited home in late summer to participate in the ceremonies to remember them. During the Chuseok Festival, held in Korea in early fall, family representatives go to the hillsides and clean off the ancestral grave mounds overgrown with weeds, holding a special banquet with the dead. Similar rituals are conducted in China at the spring “Grave-sweeping” festival each year. Such activities involve family get-togethers, feasting, and in some cases, the burning of incense, the offering of ritual foods, and ritual bowing at home or clan altars. Family connections are also reinforced at other festivals on the Lunar calendar, especially at Spring Festival in China and Korea, where it is common for youngsters to bow or otherwise honor their older relatives, who in turn present them with small gifts or money.

SHINTOISM IN JAPAN

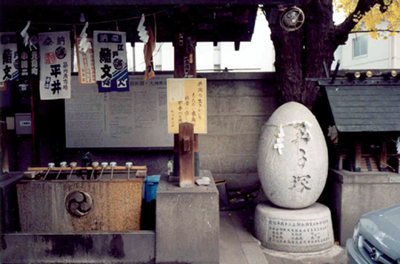

When Buddhism was first introduced to Japan from the Korean kingdom of Baekje in 552 CE, the local animistic beliefs were given the name “Shinto,” or “Way of the Gods,” to differentiate them from the new religion. Although at times there was competition among advocates of the two beliefs, overall they have existed in harmony over the ages. In many cases, Buddhist temples were built on or near the site of earlier Shinto shrines, and it is very common to find both a Buddhist temple and a Shinto shrine in close proximity in many of the temple sites (such as in Nara) today.

Among the most important beliefs in Shinto is belief in the kami (nature spirits). Kami can be anywhere—in waterfalls, rivers, mountains, strange rocks, unusual glens, or even embodied in unusual people. If treated with respect, kami can aid human beings. Thus small shrines built for local spirits are everywhere in Japan, including urban streets, parks, hills and stream banks. Among the most revered of the thousands of kami is Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, who was a key player in the mythical creation of Japan.

While the interiors of Buddhist temples are often highly elaborate, displaying huge statues and paintings, the interiors of Shinto temples (many made of cypress wood) are noted for near emptiness. Although lacking an abundance of artwork and religious imagery, a powerful presence can often be felt in Shinto shrines, which are regarded as the residence of the local spirit.

A key idea in Shinto is that of purity, and all visitors must be properly purified before entering a shrine. To this end, a feature commonly encountered outside Shinto sites is a spring at which visitors can rinse their hands and mouths before proceeding into the grounds. In some instances, a Shinto priest (kannushi), who is a caretaker of the shrine, may whisk visitors with a white paper wand as part of the purification process. This emphasis on purity is a strong theme in Shinto, and carries over into everyday Japanese life. The mirrors sometimes seen in Shinto shrines represent the pure, unspotted mind of the resident kami. Shinto rituals follow a pattern of purification, offerings to the kami (at least rice, salt, and water), prayer, and a feast (which may be very minimal).

Visitors will notice stands of zig-zag white paper (gohei) set before the doors of the sacred inner chamber of a shrine. The papers, attached to slim wooden wands act as an offering and as a marker of the presence of the spirit. Another common feature is a twisted rope (shimenawa) from which folds of paper and small bundles of flax dangle. This rope (and specially twisted ropes hanging at entryways, the base of sacred trees, or other special places) marks the boundary between sacred and non-sacred. Within the inner shrine, and always unseen, is at least one divine symbol or object, in some cases it is a hidden mirror. Other symbols that may be present are a sword and jewels. In front of the inner shrine is a space for the presentation of offerings. Purification wands may also be present. In some cases visitors can pull on a rope to ring a brass bell-gong; nearby may be an offering box for monetary contributions. Visitors to Shinto shrines can find their way by looking for a torii (“bird-perch”), which comes in several styles and indicates that a shrine is nearby, often marking the entry pathway. Among the most famous Shinto shrines are the one at Ise (southeastern Honshu Island) and the Izumo Taisha located near Hiroshima on Honshu island.

During WWII, Shinto was given the position of a state religion in Japan and special emphasis was put on the emperor, whose family is believed to be descendants of Amaterasu. In the post-War era, however, the political sanction of Shinto was withdrawn. Today Shinto has special meaning for many, if not most, of the Japanese people and is an important reference point in understanding the culture.

FORMAL BELIEF SYSTEMS

DAOISM/TAOISM

Often regarded as a compliment to Confucianism, Daoism (Taoism) developed early in Chinese history. The term “Daoism” is based on the Chinese word meaning “way” (dao) or “path.” This “way” is regarded as a cosmic force that permeates and underlies all phenomena. The goal of Daoism is to attune one’s self with the Way, an attunement that is realized by the principle of “no action” (wuwei). By opening one’s self to the natural flow of the Way, one can achieve all, yet do so without creating strife and discord. A major metaphor in Daoist thinking is that of water. Water may seem weak and yielding, yet it is that characteristic of yielding that gives it its power.

Many versions of the basic Daoist written texts have been translated into other languages. These texts are known as the Daodejing (“the scripture of the way and virtue”) and Zhuangzi. The former text is attributed to the legendary founder of Daoism, Laozi (“old one”). Legends say Laozi was from southern China and lived in the Zhou dynasty about the same time as Confucius. Some stories even say that when Laozi was the archivist for the state of Zhou, Confucius visited him to ask about the proper way to conduct certain ceremonies. So impressed with Laozi’s cultivation and knowledge of the Way, Confucius is said to have regarded him as a sagely master and likened him to a powerful dragon.

One famous anecdote reports that when Laozi was nearing the end of his life he rode off to the West on the back of a black ox. Arriving at the border, the gatekeeper persuaded him to write down the two-part text of the Daodejing. The two parts (the “Way” and the “Virtue”) are written in poetic style, and comprised of a series of short, pithy poetic passages. The general tone of Daoism is revealed in the first lines, which go: “The Way that can be spoken of is not the true Way.” This idea suggests that the nature of the Way is beyond human description and must be realized (though never fully grasped) by practice and intuition. Among the themes of the text are statements on the nature of the Way, virtue, conduct, and advice to rulers on how to run a kingdom. Click here to view a flash show of a Daoist temple.

The Zhuangzi, attributed to another legendary figure known as Zhuangzi (Chuang-tzu), is a series of anecdotes, written in prose, that illuminate aspects of seeking and realizing the Way, especially in terms of personal freedom. Many anecdotes deal with lessons on being, based on observation of skilled everyday craftsmen and working people. One famous anecdote concerns a butcher who is so in tune with the Way that his knife never goes dull. Another concerns an ancient tree that survives because its twisted trunk is of no interest to woodcutters. Possibly the most famous of the Zhuangzi tales is that of Zhuangzi and the butterfly. According to the story, Zhuangzi was sleeping beside a river when he dreamed of a butterfly. As he awoke, it was unclear to him whether he was really awake, or still dreaming. He wondered whether he was Zhuangzi dreaming of a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming of Zhuangzi. This and many other stories in the Zhuangzi question the basic “realities” and perceptions of daily life that block realization of the Way.

As noted, the Three Teachings have co-existed and influenced each other for centuries in East Asia. Certain grounds of inquiry in Daoism are similar to those in Zen Buddhism, also concerned with the problems of self-realization and existence. In a more popular vein, once the Buddhist idea of reincarnation reached China, Daoist believers soon created the notion that Laozi has had many rebirths (in every succeeding age), even appearing in the form of Buddha. Guan Yin, the Buddhist “Goddess of Mercy,” sometimes appears in Daoist stories of the Eight Immortals (introduced below). The Zhuangzi also includes several anecdotes about the actions and thoughts of Confucius relating to the Way, especially thoughts about undivided will and concentration of spirit. In this passage, Confucius is reported to have made this remark on archery:

“When you’re betting for tiles in an archery contest, you shoot with skill. While you’re betting for fancy belt buckles, you worry about your aim. And when you’re betting for real gold, you’re a nervous wreck. Your skill is the same in all three cases—but because one prize means more to you than another, you let outside considerations weigh on your mind. He who looks too hard at the outside gets clumsy on the inside.”

(Watson (1970) from the chapter entitled, “Mastering Life,” p. 201)

Daoist practitioners, including sage hermits who would often spend their lives in remote mountain hermitages, were in constant search for harmony with the Way. Though Daoism seldom received the government sanction that Confucianism, and occasionally Buddhism, enjoyed, at times Daoist practitioners were invited to the Imperial court to take part in philosophical debates between Confucians, Buddhists, and Daoists. On many occasions, emperors sought the advice of Daoist sages on techniques for obtaining immortality, as it was believed that Daoist practitioners held the key to eternal life. Breathing techniques, special elixirs of immortality, and even arcane sexual practices were all utilized by those on the path to immortality. It is said that the alleged elixirs of immortality concocted by some Daoist magicians contained mercury, and shortened, rather than lengthened the life of certain emperors.

Daoism’s contributions to popular religion (local beliefs organized on family or community levels) are many. A large pantheon of gods has grown up under Daoist influence. These supernatural beings range from the Jade Emperor of the heavens, the Queen Mother of the West (one of the prime creators of the earth), the Yellow Emperor of the most ancient times, to Laozi himself, as well as the humble, village-protecting Earth God, and the Kitchen God found in each home. The most powerful of these beings may affect human fate or, on a lower level, help to bring harmony to communities and households. In many homes in East Asia, incense and offerings of fruit are presented at home altars each day to seek favor from such gods.

The Eight Immortals

Associated with Daoism, there exists a whole host of beings that bring good luck and ward off evil. The best known of these beings are the Eight Immortals, all of whom were once actual humans who later attained immortality. The Eight Immortals are 7 male and 1 female figure (He Xian’gu), several of whom attained immortality with the help of Daoist masters. While not part of the earlier Daodejing or the Zhuangzi, written centuries before the creation of Daoist folk religion, the Daoist quest for immortality certainly stimulated the rise of beliefs about these characters in succeeding centuries.

THE HERITAGE OF CONFUCIANISM

Confucianism is a belief system that is much more concentrated on harmony in family and society than on concerns with an afterlife or an unseen spirit world. Though recognizing ultimate cosmic power, Confucian thought has stressed the development of strategies for managing states based on education and ethics. The influence of Confucianism was pervasive in Chinese and Korean culture and had a significant influence at various times in Japan’s past. Even today, influences from the Confucian tradition are strong in East Asia and it is important to understand the basics of the belief system.

Confucianism takes its name from Confucius, whose name in Chinese is Kong Fuzi (“Confucius” is a Latin version of the name) or simply Kongzi. Confucius was born into a poor family in a small feudal state in the area known as Chu Fu in present-day Shandong province. Never attaining a high official position in his life, Confucius became a valued advisor to many local rulers of the day and transmitted his teachings to his many students. His contributions and accomplishments were only fully recognized after his death. As Confucianism developed over the ages, other thinkers like Mencius (Mengzi), Xunzi (Hsun-tzu), and Zhu Xi (Chu Hsi) contributed to the discussion of how to interpret and expand upon his ideas.

Known as China’s greatest philosopher and educator, Confucius was China’s first private teacher, devoting his whole life to teaching for the purpose of transforming and improving society. While there is disagreement over scholars about who and when writings attributed to him were written and edited, the core of Confucian philosophy lies in the series of sayings known as The Analects (Lun Yu). Other works attributed to Confucius are the Book of Songs (Shijing),The Book of Rites (Li Ji) and On Filial Piety (Xiaojing).

Among the sayings of The Analects that still resonate across the centuries are:

|

The Analects of Confucius |

|

“The Master said, He who rules by moral force (te [de]) is like the pole-star, which remains in its place while all the lesser stars do homage to it.” (p. 88) “Meng Wu Po asked about the treatment of parents. The Master said, Behave in such a way that your father and mother have no anxiety about you, except concerning your health.” (p. 89) “The Master said, A gentleman can see a question from all sides without bias. The small man is biased and can see a question only from one side.” (p. 91) “The Master said, He who learns but does not think is lost. He who thinks but does not learn is in great danger.” (p. 91) “The Master said, A gentleman takes as much trouble to discover what is right as lesser men take to discover what will pay.” (p. 105) “The Master said, I could try a civil suit as well as anyone. But better still to bring it about that there were no civil suits!” (p. 167) “The Master said, The gentleman calls attention to the good points in others; he does not call attention to their defects. The small man does just the reverse of this.” (p. 167) “The Master said, If the ruler himself is upright, all will go well even though he does not give orders. But if he himself is not upright, even though he gives orders, they will not be obeyed.” (p. 173) Source: Waley, Arthur, trans. (1938). The Analects of Confucius. New York: Vintage Books. |

His philosophy laid the groundwork of ancient Chinese ethics and ideology and became the philosophical cornerstone for East Asia. A basic idea in Confucian thought is that leaders in society should cultivate their ethical principles and behavior in order to act as examples in society. Thus, it was thought the duty of all those in higher relationship positions to act as models for those in lower positions. Following this idea, generations of scholars in China and Korea studied the writings of Confucius in order to sit for civil service examinations leading to civil government positions. Education is still a prominent feature in each of the major cultural areas in East Asia today.

Confucianism and the Five Relationships

The Five Relationships (Wu Lun) are the basis of the Confucian model of social order and reflect the dream of a well-ordered, harmonious society. That harmony is based on the underlying principle of cosmic order, reflected in social order when everything is in balance. In a given situation, each person is in one of the role categories in the hierarchy of relationships. Each role has its own duties and responsibilities. If everyone properly fulfills them, then society will be harmonious and all will benefit. In the words of Confucius, “Let the ruler be ruler, the minister be a minister, the father be a father, and the son be a son.” Although these prescriptions were not always carried over into real life situations, for centuries they set the social parameters in much of East Asia.

The Five Relationships

1) Emperor to Subject: emperors are to be good examples of proper behavior; they should care about their subjects and inspire their subjects to do likewise to others.

2) Father to Son: fathers are to be models for their sons, who in turn are to respect and honor their parents. This principle of honoring and caring for parents is know as “filial piety” (xiao). Confucius considered this a basic societal principle. By implication, daughters and mothers have a similar relationship, though a woman’s situation was complicated by the fact that when she was married, she left her family of origin to live in her husband’s home, where she was expected to be filial to her parents-in-law.

3) Husband to Wife: husbands are the heads of households and responsible for upholding family honor; wives are responsible for bearing (male) children to carry on the family name.

4) Elder Brother to Younger Brother: elder brothers should be good models, while younger brothers should be respectful; mutual love and care are expected.

5) Friend to Friend: be true, faithful, and helpful to each other—in other words, cultivate real friendships.

Some Basic Concepts in Confucianism

It is important to be aware of several basic concepts in the Confucian belief system. Although interpreted differently over time, and subject to debate among Confucian scholars, the following basic concepts will be briefly defined.

Three Important Confucian Thinkers

Mencius (Mengzi) (372-289 BCE): This great thinker was a student of Confucius’ grandson. In debates among scholars about human nature, Mencius advocated the idea of the “original goodness of human nature.” He felt that human nature is essentially good and only no education or poor education can cause a person to go bad. Furthermore, he felt that people should be judged by learning, and not simply by family background. Eventually, China developed a civil service examination system, allowing talented males to achieve official positions by effort, rather than birth. In his ideas about the Mandate of Heaven, Mencius advocated the idea that the common people had the right to revolt if living conditions became intolerable due to misgovernment.

Xunzi (Hsun Tzu) (298-238 BCE): Xunzi’s ideas were often nearly opposite to those of Mencius—though both thinkers saw the need for education. He felt that human nature was basically bad and needed the correction of good education. Thus, strong governments and strict social order were needed to keep people’s evil nature in check. His thinking influenced the development of Legalist ideas that were used during the rule of China’s first emperor, Qinshi Huangdi.

Zhu Xi (Chu Hsi) (1130-1200 CE): This thinker was a major figure in the rise of a new wave of Confucian thinking called Neo-Confucianism that emerged in China in the 11th and 12th centuries. Zhu’s thoughts revisit and extend earlier ideas on human nature and self-cultivation. Like Xunzi, Zhu Xi saw education as critical in the development of true understanding and he recommended prolonged study and meditation on the most important of the Confucian writings, by then known as the Four Books and Five Classics. His ideas had a great influence on Korean Confucian scholars such as Yi Hwang (1501-1570 CE) and later on Japanese scholars in the mid-19th century when Japan re-instated direct imperial rule.

|

|

|

Three Important Confucian Thinkers |

||

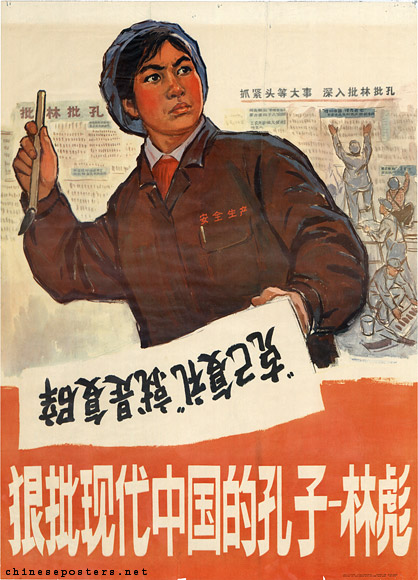

Confucianism Today

Confucianism today retains a powerful legacy in East Asia. Although the Confucian classics are no longer memorized by aspiring civil bureaucrats (the exams ended in 1905), and Confucius was even vilified as backward, oppressive, and feudal during the chaos of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) in China, the stress on education, self-cultivation, propriety in word and deed, and family as the basic social unit are still current (though sometimes only implicit) throughout East Asia. Confucian ceremonies are still held at Confucian temples in Korea, Taiwan, and recently again at the birthplace of Confucius in Shandong, China. Some observers have even suggested that East Asia’s rise to economic prominence during the last decades is due in part to the positive aspects of Confucianism, especially the stress on properly fulfilling the duties of one’s social role and the stress on education.

The BUDDHIST HERITAGE

Buddhism is the only one of the Three Teachings not native to East Asia. An imported belief tradition, Buddhism originated in a part of northern India that is now the country of Nepal. Growing out of earlier Hindu beliefs, it is based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama (c. 556-483 BCE).

Known as Gautama Buddha, he was the son of the ruler of a small kingdom. Legend has it that he was born out of the side of his mother, Maya (a name meaning “illusion” in Sanskrit). Leading a privileged and luxurious life within the palace walls, young Siddhartha became curious about life outside the palace. On a trip outside the walls, he encountered sick and dying people and began to realize that the life he was enjoying was indeed an illusion. Later, he gave up his wife and inheritance and took to the hills to become an ascetic. After many seasons of meditation, he achieved enlightenment while sitting under a great tree. He then set about on a career of teaching to the masses in order that all sentient beings might someday escape from the cycle of life and death and achieve ultimate realization, or enlightenment. An important Buddhist concept is that of nirvana. This is when one is freed of all egotistical cravings and enters into the Void. It is a state of selflessness, nothingness, an ending of samsara, the cycle of rebirth or reincarnation.

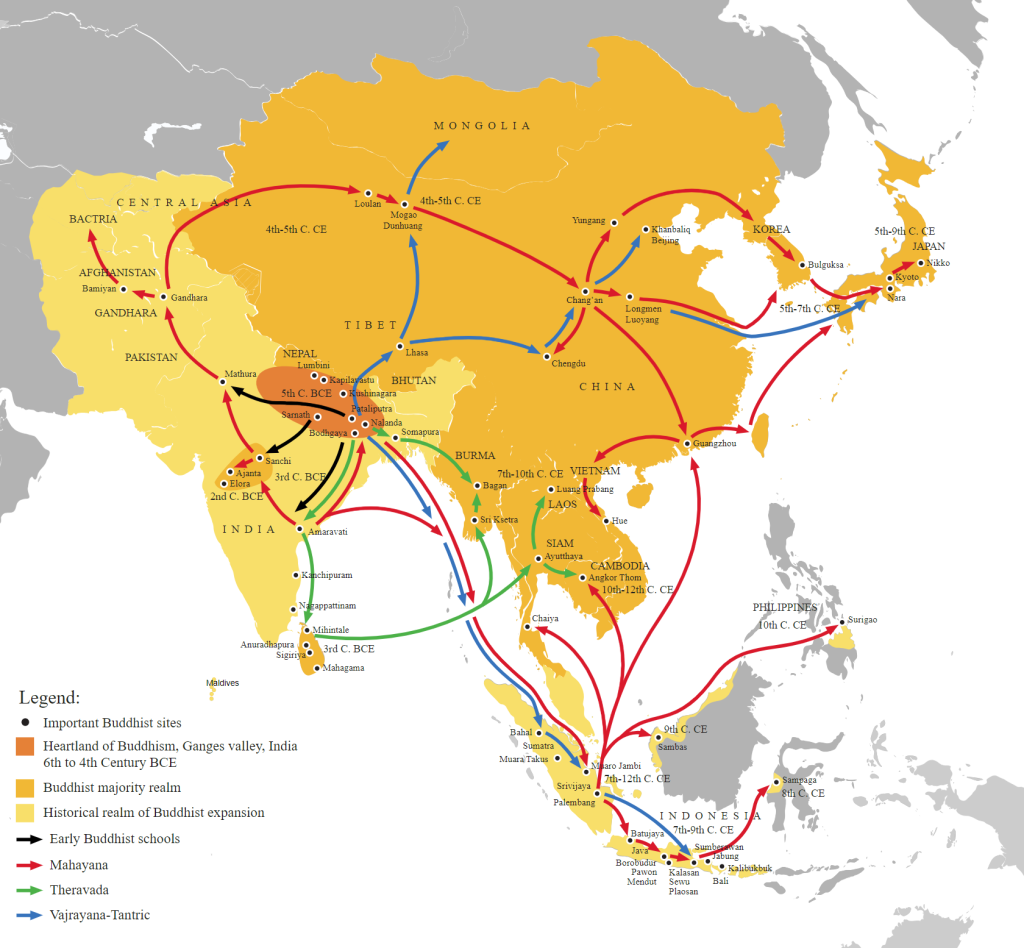

After Buddha’s death, monks and missionaries carried his teachings of salvation far and wide throughout India. By the 1st century CE, monks carried Buddhism into northwest China on the Silk Road and along other trade routes leading into what is now southwest China. After Buddhism established a foothold on the Korean peninsula in the 4th century CE, it was carried to Japan by the 6th century. It was actively promoted during the reign of Prince Shotoku, taking a place alongside native Shinto beliefs. In India Buddhism was eventually re-absorbed into Hinduism, though it remains strong today in Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, and East Asia.

As Buddhism spread outside of India, it gradually transformed, modified by the different cultures that accepted it. As Buddhism developed in China, for instance, the idea of the “nothingness” of nirvana changed into the idea of a “pure land” or paradise that was a world of permanence, peace, and bliss that the soul of the dead entered after death. This concept accorded better with the optimistic worldview of Chinese culture and aided the efforts of missionaries spreading the doctrine to the masses. Also, the best-known of the many Buddhist “bodhisattvas” (something like Christian saints) is Avalokitesvara (a Sanskrit name, from India), known as Guanyin in China and Kannon in Japanese. The being was originally portrayed in artwork as male but was later transformed into a female figure under the influence of Chinese culture.

In East Asia today Buddhism is a major religion with many branches, and is especially popular in Japan and South Korea, where it complements other traditions such as Daoism and Shinto. Since many monasteries were places of study and learning, over the centuries Buddhism has contributed greatly to traditions of art, architecture, literature, philosophy, social structure, history, music, mathematics, and medicine.

|

|

Basic Concepts and Ideas of Buddhism

The following charts contain the basic concepts of Buddhism based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha. The Four Noble truths are the basis of Buddha’s enlightenment. In order to obtain enlightenment, people should attempt to act correctly in accord with the Eightfold Path (which emphasizes the right way of living) and the Five Precepts (ethical rules).

The Four Noble Truths

2) This suffering and general dissatisfaction come to humans because they are possessive, greedy and, above all, self-centered;

3) Egocentrism, possessiveness and greed can, however, be understood, overcome, and rooted out;

4) This rooting out can be brought about by following a rational Eightfold Path viewpoint. (Ross, p. 91)

The Eightfold Path

(2) Right purpose (or aspiration)

(3) Right speech

(4) Right conduct

(5) Right means of livelihood (or vocation)

(6) Right effort

(7) Right kind of awareness or mind control

(8) Right concentration or meditation (Ross, p. 92)

The Five Precepts

1) Do not kill.

2) Do not steal.

3) Do not be lustful.

4) Do not be light in conversation.

5) Do not drink wine.

The following is a list of basic Buddhist views, many of which resonate in the Eightfold Path and the Five Precepts.

- There is no origin or ending of the universe.

- Change is the only constant: the four elements of the world—earth, water, fire, and wind—are always in a state of change.

- Human cognition is limited; there is no absolute, objective truth.

- Wisdom is needed to overcome wrong beliefs, wrong feelings, and wrong behavior.

- Love (in a broad sense) is directed towards Buddha, the ideal life, wisdom, society, relatives, friends, to animals and all other sentient beings.

Major Branches of Buddhism

Two major branches of Buddhism developed over time. The earliest one is known as the Southern School (Theravada). In this school, there is the idea of selective monkhood—that is, only certain persons (nearly all male) are eligible to be monks. This school is still popular in parts of Southeast Asia and in the Xishuangbanna area of Yunnan province, located in southwest China. The Northern School was brought into China on the Silk Road and proclaimed itself as “Mahayana” or “Great Vehicle.” It is the dominant form of Buddhism in East Asia and has a salvationist message. In the Southern branch, the basic way of practicing Buddhism is to become a monk, while in the Northern form; it is normal to practice it in daily life.

Many schools of Buddhism developed from the Mahayana branch, especially in Japan. Among the most important is the “Pure Land” sect, which takes the reading of the famous Buddhist scripture, the Lotus Sutra, as its main religious text. Simply by speaking the name of Lord Buddha, one is guaranteed a place in the Pure Land after death. In a quite different direction, Zen developed as a special school of Mahayana Buddhism with a strong emphasis on personal enlightenment under the guidance of a meditation master. Many Zen practitioners in Japan and Korea spend months or years in rigorous routines of meditation in their quest for enlightenment. Zen is possibly the best-known type of Buddhism outside of Asia. Originating in India, Zen was brought to China by the missionary teacher Bodhidharma in the 6th century CE. In China, it absorbed influences from the two major Chinese belief systems of Daoism and Confucianism. Known as “Chan” in Chinese and “Son” in Korean, the name “Zen” originated in Japan, where by the 13th century it became an important aspect of the Japanese cultural aesthetic. Zen stresses disciplined striving for knowledge of self and reality beyond the egocentric self. Meditation under the guidance of a master is a common form of practice for many practitioners. Many meditative practices are designed to create situations in which everyday “reality” is shaken in order to allow for the eventual realization of the illusion of a separate, fixed self and of the “oneness” of everything. The stress is on attaining insight through the enactment of the simplest things so that with the right mind, perceptions change. This principle is illustrated by an old Zen saying:

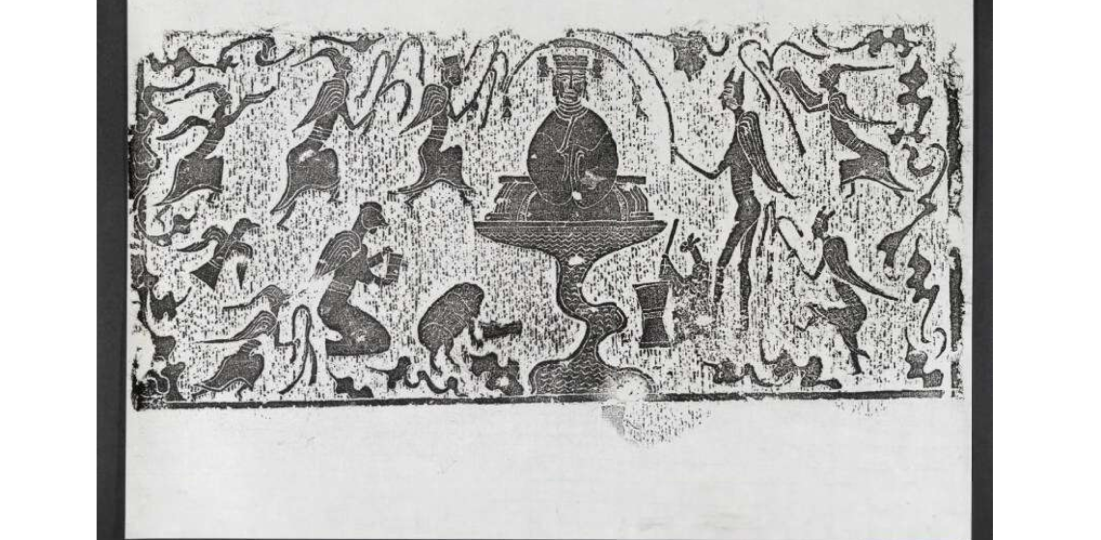

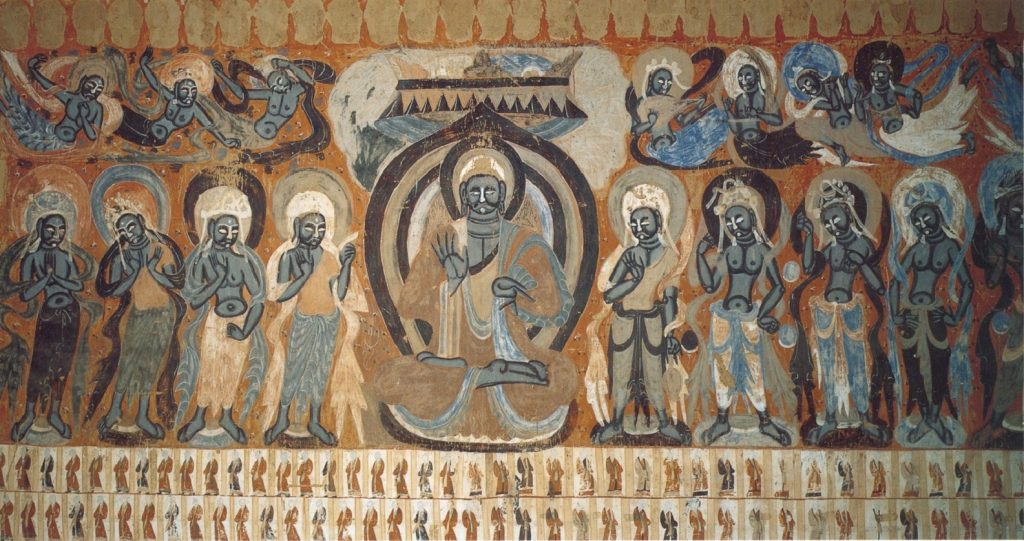

Many of the important artworks in China, Korea, and Japan during the period from about the 4th to 11th centuries were strongly influenced by Buddhism. Temples throughout the region are among the greatest architectural feats of the ancient world. Outstanding examples of Buddhist art in East Asia include the murals in the 400+ caves in the Dunhuang Grottoes in Gansu province and the amazing statues carved from the cliffs at the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang, Henan province, China.

Other great works are the white granite Seokguram Buddha, near Gyeongju, South Korea, and the gigantic iron Buddha in the Todaiji Temple in Nara, Japan. In Tibet, distinct forms of Buddhism also developed, along with a rich artwork exemplified by temple wall murals and thangka scroll paintings. Moreover, important forms of Chinese oral literature grew out of the popular teaching style of Buddhist monks who adapted Buddhist stories for popular consumption in their missionary efforts. In the early 20th century in a cave at Dunhuang, scholars discovered a cache of about 30,000 ancient texts, including many works of literature called “transformation texts” (bianwen). These texts were both Buddhist and secular stories told in alternating passages of prose poetry and dated from before the 8th century CE.

|

|

|

Important Terms in Buddhism

The following is a list of words commonly encountered in studies of Buddhism.

Bodhisattva: a being who has already achieved enlightenment but who “stays behind” in human form out of compassion in order to help others achieve enlightenment; acts as a model of generosity, good conduct, vigor, patience, meditation, and wisdom

Karma: “deeds”—a person’s speaking and action that decide his/her fate in his/her next incarnation

Samsara: the wheel of life and death (reincarnation)

Sutra: a Buddhist scripture

Mudra: hand gestures, often represented in paintings and sculptures of Buddha

Dharma: the teachings of Buddha

Nirvana: the state of “nothingness” achieved after enlightenment

Thangka: a painting depicting aspects of Buddha and Buddhist cosmology in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition

Tasting Vinegar

The Three Teachings have interacted in East Asia for centuries. A popular story is that of Laozi (Daoism), Buddha (Buddhism), and Confucius (Confucianism) tasting vinegar from a common vat. Each had a different expression on tasting the vinegar. Confucius found it sour (suggesting a need for principle and order in human life), Buddha found it bitter (suggesting existence is suffering), and Laozi found it sweet (reflecting harmony with the natural way). On one level the Three Teachings all broach different approaches to human existence, yet dip from a common pot of cultural heritage.

OTHER HERITAGES OF BELIEF

Besides the Three Teachings, animism, shamanism, and ancestor reverence, other beliefs are also present in East Asia. Islam has a strong following in parts of China, especially the northwest, with tens of millions of believers among ethnic minority groups such as the Hui and Uygurs. Judaism and forms of Christianity (such as the Nestorian sect) were introduced into China on a small scale during the early Silk Road era, and in the city of Kaifeng today there is still a small Jewish community. During the 19th century, many Christian missionaries from the United States and Europe set up missions all over China and today there are several million believers. Over 30% of South Koreans are presently Christian (some estimates place the figure higher), the highest percentage in East Asia. Japan has hundreds of small local religious groups that have developed in modern times and often involve the worship of various local gods. Although China is officially an atheist state, religious tolerance grew with the introduction of economic reforms in the 1980s, though in some ways such tolerance has been tempered in recent years.

|

|

Marxism in East Asia

Marxism, first developed by German thinker Karl Marx in the 19th century, is an influential economic and political ideology, or system of thought, born of Marx’s attempts to understand and remedy the vast inequities that had evolved in Western societies during the Industrial Revolution. Marx came to critique private property (capital) ownership as the lynchpin of a system of class-based political and economic oppression. He further argued that the workers exploited and suffering under this system of capitalism would inevitably overthrow it in reaction, take power, and create equitable “socialist” societies in which property was owned communally—i.e. socialized. Marx’s thought as it was subsequently developed in East Asia during the 20th century (with input from Leninism in the Soviet Union), especially by Mao Zedong and other Chinese leaders, became a major influence on world view in both China and the Korean peninsula where Marxist-influenced communists led revolutions that founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) or North Korea. This ideological influence continues into the present in both countries. In China, the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was celebrated to great fanfare in July 2021, and, as detailed below, what has come to be called “socialism with Chinese characteristics” continues to guide the official policies of the government on all levels. Though the system based upon Marxist thought has evolved very differently in North Korea, the country’s leadership continues in the hands of the family of Kim Il-sung, the communist leader and fighter who founded the state. Like the PRC, North Korea is also officially atheist.

The CCP was created by a small group of Chinese intellectuals in Shanghai in July, 1921, during the period of intellectual ferment known as the May Fourth Movement. Over the ensuing decades of invasion and civil war, the theory of Marxist-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought was developed, and “New China” was declared in 1949. The practical application of the theory in China involved the “awakening” (xinglai) of oppressed workers and peasants to the oppressions of the capitalist and landlord classes. Mao’s contribution to the theory adapted it to China’s early 20th century reality as an agrarian-based society, promoting revolution among the vast Chinese peasantry, especially during the Anti-Japanese War, Civil War, and the Land-Reform movement of the 1950s. Peasants (nongmin), following a “mass line,” were given language to “speak bitterness” (su ku) at struggle sessions against local landlords whose landholdings, on which many peasants rented under often exploitive conditions, was confiscated and reallotted for communal use by the peasantry. Similar confiscations and re-divisions of property and the means of production were carried out in cities. After decades of experiments with class struggle, collectivism, and mass movements, a new branch of thought called Deng Xiaoping Theory was later added to the core political theory. Deng Theory recognized the utility of combining aspects of a market economy with openness to the outside world, unleashing productive forces in new ways. During the 1980s and into the early 2000s pragmatic Deng Xiaoping Theory was the underlying force of development behind the huge economic growth in China. In 2012 Xi Jinping became president of the PRC, ushering in the age of the “China Dream” that sought to tame the excesses of corruption that had developed in the period of rapid growth; to seek poverty alleviation in remote rural areas; to lead the Chinese people to develop a moderately prosperous standard of living and advanced society with “common prosperity”; and to turn China into a powerful world leader (with the emblematic “One Belt, One Road” infrastructure and trade project as a key strategy). In 2017, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era” was added to the Chinese constitution and is widely promoted today in various media and educational channels among the 95 million Party members and general public.

|

|

Selected sources:

Adler, Joseph A. (2002). Chinese Religious Traditions. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Giles, Lionel (1948). A Gallery of Chinese Immortals: Selected Biographies Translated from Chinese Sources. London: John Murray.

Ho, Man Kwok and Joanne O’Brien (1990). The Eight Immortals of Taoism: Legends and Fables of Popular Taoism. New York: Meridian.

Ivanhoe, Philip J. (2000). Confucian Moral Self Cultivation. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Lopez, Donald, S., ed. (1996). Religions of China in Practice. Princeton: Princton University Press.

Mote, Frederick W. (1989). Intellectual Foundations of China. New York: Afred A. Knopf.

Ross, Nancy Wilson (1966). Three Ways of Asian Wisdom. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Sidky, H. (2020). The Origins of Shamanism, Spirit Beliefs, and Religiosity: A Cognitive Anthropological Perspective. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Watson, Burton, trans. (1970). The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, Columbia University Press.

Wemheuer, Felix (2019). A Social History of Maoist China: Conflict and Change, 1949-1976. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

- Shamanism and Ancestor Reverance

- Daoism

- Buddhism

- Shinto

- Religion in Korea

- Confucianism

- Innovation