9 Module 8: Literature In East Asia

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

INTRODUCTION

Each of the 3 major cultural areas in East Asia have strong literary traditions, and harbor some of the world’s greatest literature. China’s vast literary heritage includes 40,000 poems that exist from the Tang dynasty alone. The Tale of Genji, from 7th century Japan, is considered by some scholars to be the world’s first novel. The Korean vernacular story about the heroine Chunhyang was made into an internationally acclaimed film.

The categories used to describe traditional literary works and their social use and position is somewhat different in East Asia than in other literary traditions. In the European tradition, poetry, epic, and drama—and in more recent centuries—romance, novel, and short story are familiar categories.

Up until the late 19th and early 20th century, however, major literary accomplishment in East Asia (regardless of culture), has centered on poetic traditions. Since the Tang dynasty, upper class males were expected to memorize and compose classical poetry as part of the civil examination system in China and Korea. Love letters written in verse were exchanged between men and women of the imperial court in Heian Japan. In all 3 cultures, knowledge of the poetic tradition and the ability to compose poems at banquets, on outings in a scenic garden or mountain pavilion, or other social gatherings was expected, and served as a mark of cultivation.

There was also a lively interplay between the orally performed songs of entertainers and the literary tradition. In some instances, literary men in China imitated the verses of professional female entertainers or wrote material for the women to sing. Similar situations existed in Korea and Japan. In many instances, it was normal to read literary texts out loud—especially poetry—or to recite them from memory.

Long works of prose fiction were also popular in East Asia, especially after the widespread introduction of mass-produced books by the 16th century. Many of these works were written in a vernacular language that was much closer to daily speech than the refined classical language used in much of the poetry. Shorter tales were also popular. Urban people were especially interested in fiction as a form of entertainment and many stories feature unusual (or even weird) plots and colorful characters that include common townspeople, as well as the occasional ghost, goblin, monster, or shape-shifting fox-fairy. Some stories seem to have been adapted from oral performances of storytellers, and in many cases, stories appear in several genres including written fiction, oral storytelling, and dramas (which were also printed, as well as performed).

A very popular form of literature that spread throughout all of East Asia was prosimetric narrative. Prosimetric means the combination of poetry and prose in storytelling, whether in oral storytelling sessions or in print. The prosimetric form may be traced to Buddhist sermons preserved from the 7th century CE (or earlier). Over 20,000 prosimetric manuscripts in eight languages were found in the caves in the Silk Road city of Dunhuang, China early in the 20th century. Many manuscripts concerned Buddhist tales from India, while a number were also fictional entertainment. Over the centuries, prosimetric forms of various types appeared all over East Asia. Some of the longest works of Chinese literature (many written by women) are a type of prosimetric fiction. The Korean story about Chunhyang, mentioned above, is also in prosimetric form.

Epic poems that date back hundreds of years are found among some of the ethnic minority peoples of western China. A number of written versions of these extremely long oral poems (some scholars say, the longest ever recorded) have been published over the last few decades. They include the story of King Gesar (in both Tibetan and Mongol versions); the story of Jangar, a Mongol hero; and Manas, a Kirghiz hero. Shorter narrative poems about the creation of the sky and earth are common among many minority groups in southwest China. Since the late 19th and early 20th century, the influence of Western literature has been felt strongly in East Asia. Although classical poetry is still written, and certain aspects of traditional fiction carry on in today’s literature, Western-inspired novels, short stories, poetry (free verse, in particular), and drama, have become mainstream mediums of literary expression, alongside vibrant film industries.

LITERATURES OF CHINA

Poetry

As noted earlier, poetry was the major genre of creative literature throughout most of Chinese history. The earliest Chinese poetry is a collection of oral poetry called the Book of Odes (sometimes called the Book of Songs, or Shijing, in Chinese) from the Zhou dynasty (1100-221 BCE). The Odes is comprised of over 300 songs that were collected among the rural folk and then polished by scholars of the royal court. Themes include songs of love, nature, longing, and ritual. The rulers felt that by collecting and examining the folk songs of the people, they would have a better idea of who they were ruling. This early collection of poetry is traditionally attributed to Confucius, but its real origin is unknown. Here are two pieces from the collection:

“Lies a Dead Deer”

Lies a dead deer on yonder plain

whom white grass covers

A melancholy maid in spring

Is luck

for lovers.

Where the scrub elm skirts the wood,

be it not in white mat bound,

as a jewel flawless found,

dead as doe as maidenhood.

Hark!

Unhand my girdle-knot,

stay, stay, stay

or the dog

may

bark.

(translated by Ezra Pound)

“Plop fall the plums”

Plop fall the plums; but still there are seven.

Let any gentleman that would court me

Come while it is lucky!

Plop fall the plums; there are still three.

Let any gentleman that could court me

Come before it is too late!

Plop fall the plums; in the shallow basket we lay them.

Any gentleman who would court me

Had better speak while there is time.

(translated by Arthur Waley)

Both poems are about love in early China and reflect prevailing ideas of gender, sexuality, and marriage.

Other early works include the Elegies of Chu (Chu ci), written and compiled by China’s first known poet, Qu Yuan. Some of the poems are quite mystical, dealing with the realm of the supernatural. Many legends surround Qu Yuan, and he is remembered at a special festival held in late spring. Known as the Dragonboat Festival (Duanwu), legend says that rice cakes are thrown into the rivers at this time so that the fish will not eat the body of Qu Yuan, who committed an honorable suicide after his advice to a corrupt ruler was ignored.

|

|

During the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) folksongs were again collected and compiled by a special government music bureau (yuefu). A number of these yuefu songs still survive. At this time a popular literary form was the fu, which were long prosimetric rhapsodies with excessive imagery.

The great Tang dynasty (608-906 CE) was the high point of Chinese poetry. During this time a type of poetry called shi was dominant. Instead of four words per line, as in the Book of Odes, poems had five or seven characters per line and the “regulated verse” had many strict rules about rhymes and parallel images. Since Chinese is a tonal language, it is interesting to note that poems also had special tone schemes as well as rhyme schemes. Because the pronunciation of Chinese and even the sound of the tones have changed over time, it is very difficult to try and reconstruct the sound of Tang dynasty poetry. We do know that much of it was composed to special tunes and was sung or chanted aloud.

Although all scholar-officials were expected to be able to write poetry, some stood out as poets above all others. Among the great names in the incredibly rich tradition of Tang poetry are: Wang Wei, Li Bai (Li Po), Du Fu (Tu Fu), Bai Juyi, Yuan Zhen, and the female poet and paper maker from Sichuan, Xue Tao.

Wang Wei was a painter as well as a poet. He is known for the elements of Buddhism in his nature poetry. His lyrics are often deceptively simple, yet the patterns of images he presents hold much meaning.

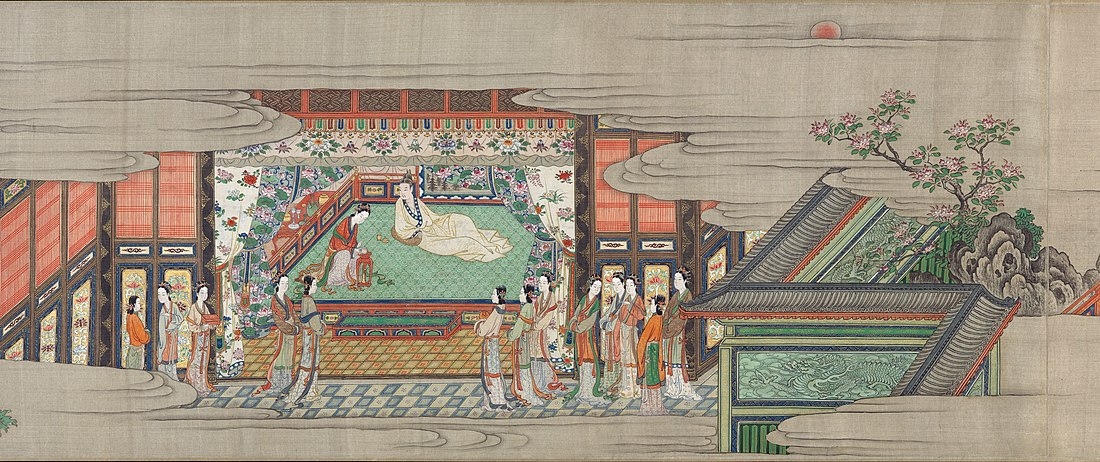

Towards the end of the Tang lived Bai Juyi (772-846 CE). Known as a “pastoral poet” because of his natural themes and his interest in country dwelling, Bai’s most famous poem “Song of Everlasting Regret” (Chang hen ge). The long poem tells of the love between Tang emperor Xuanzong and his beautiful consort, Yang Guifei. The poem describes the emperor’s infatuation with Yang Guifei and his obsession with her memory after she was implored to commit suicide by the emperor’s generals while fleeing from the capital during a rebellion. These few lines reflect how much he misses her whenever he sees the places where they once spent time together:

The lotus plants were like her face and the willow trees were like her eyebrows,

Upon seeing this, how could he hold back the tears?

Gone were the breezy spring days when the peach and plum trees were in bloom,

Replaced by the autumn rains when the leaves of the wutong trees had fallen.

(Wikisource)

See the Playlist for a complete version of “Song of Eternal Regret” in Chinese and English.

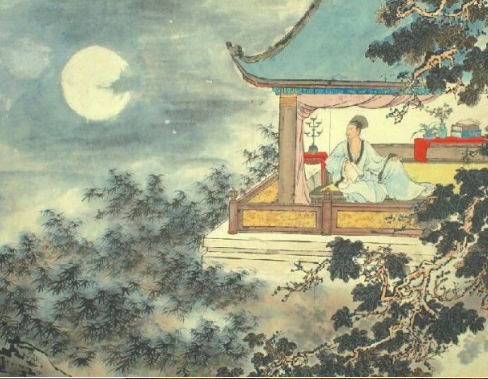

Li Bai is possibly the most beloved Chinese poet of all time, though it is possible that his homeland was on the very borders of western China. Although a true poetic genius, many stories exist of his swashbuckling behavior and his drinking bouts. One legend concerns a visit with the Tang emperor. Li Bai was so drunk he asked that his boots be removed during the audience—and was granted his wish. Another story tells how he died while trying to drunkenly embrace the reflection of the moon in a river. Mixing both Daoist and Buddhist influences in his poems, he had a keen eye for nature and mused over human existence and his place in it. Below is a translation of “Quiet Night Thoughts” (Jing ye si), one of Li Bai’s most famous and most translated poems, known to most Chinese people. The translation is given in Chinese pinyin romanization, Chinese characters, and English.

静 夜 思Chinese:

Chuáng qián míng yuè guāng

床 前 明 月 光

Before bed bright moon shines

Yí shì dì shàng shuāng

疑 是 地 上 霜

Seems like frost on ground

Jǔ tóu wàng míng yuè

举 头 望 明 月

raise head—behold bright moon

Dī tóu sī gù xiāng

低 头 思 故 乡

lower head—long for hometown

Vernacular English:

“Thoughts of a Night”

Before my bed shines the bright moon,

It seems like frost on the ground.

Raising my head to behold the bright moon,

Lowering my head in thoughts of home.

(Translated by Mark Bender and Liu Wei)

Unlike the wild Li Bai, the voice of Du Fu is serious and contemplative. His poems are strongly Confucian in their concern for society and the fate of the realm. His feelings were deep and personal. One legend tells that upon returning home after an absence of several years, he found that one of his children had starved in the war-torn region. Many Chinese see Li Bai and Du Fu as representing two sides of the Chinese spirit. (Please see the Playlist for “Spring View,” translated by Pauline Yu, for a comparison between Li and Du.)

The life story of the poet Xue Tao (c. 770-831 CE) reads like a serial drama. The daughter of a minor official from the capital Chang’an, at a very early age she moved to Chengdu in Sichuan province, where her father died. At an early age, probably because of destitution, she was registered as a professional courtesan, which meant entertaining scholar-officials. Her talent for letters was recognized by local officials and she became friends with several of the most famous poets of the Tang dynasty, including Yuan Zhen and Du Fu. Socially independent, she later became a Daoist, and became known for making exquisite paper. Near central Chengdu there remains a well from which she drew water for making her paper. This poem is one of many that demonstrate a subtle appreciation for the small things in life. (The poem is included here in remembrance of the appearance of the 17-year locusts in Ohio in summer 2021.)

“Cicadas”

Dew rinsed:

Their pure notes

Carry far.

Windblown:

As dry, fasting leaves

Are blown.

Chirr after chirr,

As if in unison.

But each perches

On its one branch

Alone.

(translated by Jeanne Larsen)

During the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE), a new form of poetry came into its own. This form, known as lyric verse (ci) followed less strict rules of rhyme and tone than did shi. New music was also composed for the lyrics, and many of them were influenced by the songs performed by professional female entertainers in the pleasure districts of the large urban areas.

Among the most famous authors of this newer form was Su Dongpo, who has a “manly” style of delivery. The most accomplished of the ci poets, however, was Li Qingzhao. Li is also regarded as the most famous woman poet in Chinese literary history. Born into an upper-class family (which was friends with Su Dongpo), she began writing poetry at a young age. Her early poems tend to be sublime and sensual, although the tone of her poems saddens after the early death of her husband. This sad feeling is fully reflected in many of her later works. Among her best-known works is “Spring at Wuling.” After the Song dynasty, both shi and ci were used for centuries, though they seldom reached the level of Tang and Song times.

|

|

Vernacular fiction and drama

Traditional Chinese fiction and drama, which rapidly developed after about the 14th century, were not held in high regard as “literature” by Chinese scholar-officials. Nevertheless, works of fiction and drama were loved by many people (including some scholars) as sources of entertainment and escape. Some of the works, such as Dream of the Red Chamber, are far more than entertainment, and offer detailed glimpses into the lifestyles, values, and patterns of social interaction of China in the late imperial period. Besides being entertaining, these popular works were expected to have at least some pretense of a “didactic” moral message—much like those in primetime American television shows that must come to a just end for all concerned. Authors of most of the works are not known, and even the most famous novel-length stories and dramas are often the product of several hands, with changes and additions appearing in different versions over time.

The cover-all term for Chinese fiction (both novel-length and short story length) literally means “small talk” (xiaoshuo), reflecting its lower status than classical poetry. Many of the traditional stories were written as if being told by an oral storyteller. They begin with a phrase something like, “It’s said that in such and such a place, in such and such a time, lived a person named …,” and include many other phrases, small songs or direct questions to the reader that suggest an oral storytelling session in the marketplace or teahouse. Chapters of the longer stories often end, “If you wish to see what happens next, read the next chapter,” just as many storytellers would say, “If you wish to know what happens next, please come tomorrow.”

Another important element of traditional fiction, drama, and professional storytelling is the interest in strange, unusual, or downright weird events. The “strange” (qi), elements of a story might include unusual coincidences, chance meetings and secret romances between gifted young scholars and lovely, talented young ladies, women dressing up as men in order to become officials, foxes changing into alluring and dangerous women, perilous love triangles and scandalous affairs, chance reunions of long-lost relatives, snowstorms in summer that reflect heavens’ will, and so forth.

Stories of the strange began to be written as early as the Tang dynasty. In the 16th century a scholar-official named Feng Menglong collected or wrote many strange stories and published them in several collections. One of the best-known stories is the love intrigue, “The Pearl-sewn Shirt.”

Of the longer prose stories, several are considered as “masterworks” of Chinese fiction. All were written between the 15th and 19th centuries, and all have several variant versions.

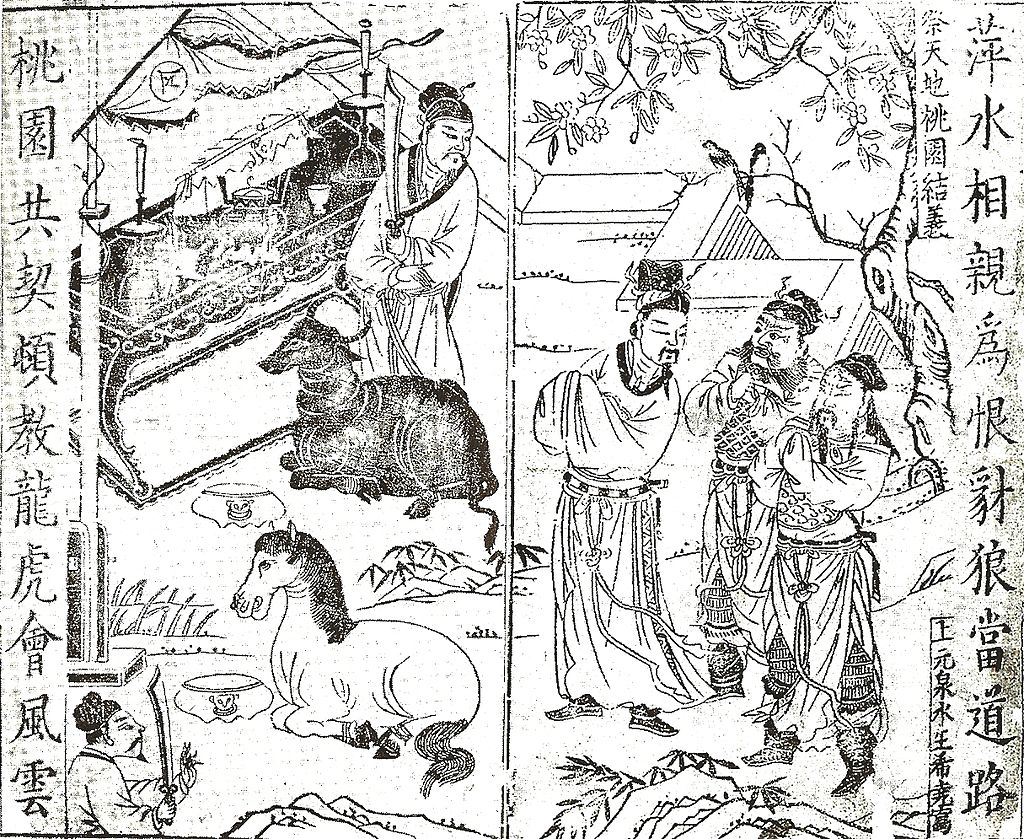

Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi) was written in Classical Chinese and is often attributed to Luo Guanzhong. The story is based on legends and historical accounts of battles and intrigues between three small kingdoms after the fall of the Han dynasty. Many Chinese operas are based on stories in this great work.

Outlaws of the Marsh (Shuihu zhuan) is attributed to Luo Guanzhong and Shi Nai’an. It tells of the exploits and adventures of a band of 114 outlaws who live in a large marsh in northern China. Many of the outlaws were actually good men (like the English folk hero Robin Hood) who went bad because of the corrupt society.

Among the outlaws are Wu Song, Lin Chong, and Li Gui, who are beloved figures in Chinese storytelling and opera, as well. In fact, many of the adventures in Outlaws of the Marsh may have derived from oral stories told in the marketplace. The passage, “Lin Chong Shelters from the Snowstorm in the Mountain Spirit Temple,” which tells how Lin Chong was framed by heartless tyrants and was forced step by step to join the outlaws, has been adapted extensively to storytelling and stage operas.

Golden Lotus (Jin ping mei), is famous for its portrayals of illicit love and sex, though offers fascinatingly detailed portraits of life of the merchant class in Ming dynasty China. Many editions of the work have blacked-out passages, indicating X-rated content. When the book was translated into English in the early 20th century, these passages were translated into Latin.

Journey to the West (Xiyou ji), written by Wu Cheng’en in a mix of prose and poetry, is a beloved Chinese story. It concerns the adventures of the monk Xuan Zang (San Zang) on his way to India in the 6th century to retrieve the Buddhist scriptures. He was accompanied on the way by a big monk named Sandy (Friar Sand), an all-too-human pig named Pigsy (Pig), and the mischievous Monkey King who could transform himself into 500 different beings. On their way, they battle various creatures such as the feared White-Bone Demon and Yellow Robe Monster.

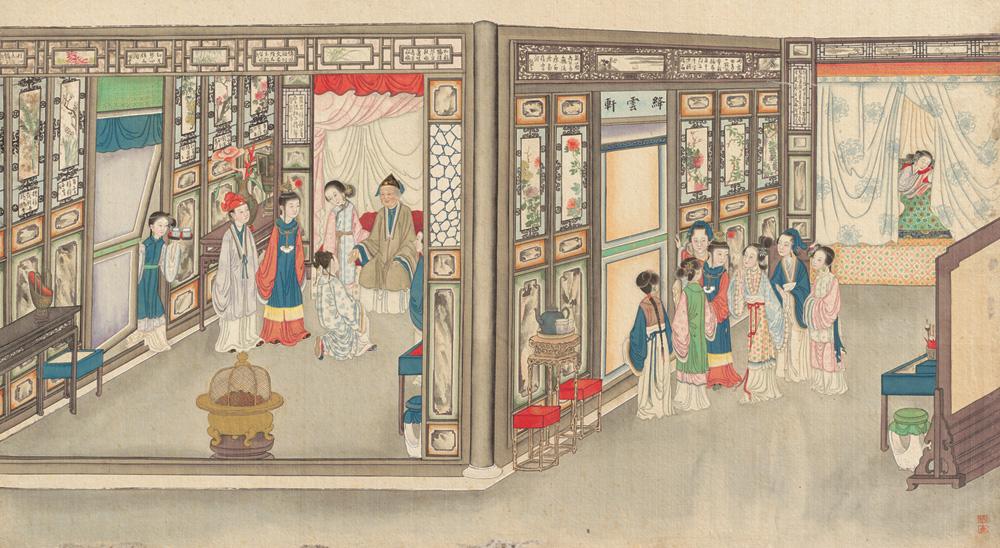

The most famous of the four masterworks is The Dream of the Red Chamber (Honglou meng), by Cao Xueqin. It concerns the life of Jia Baoyu, a sensitive young man who grows up in an aristocratic household filled with lovely and talented young women. With over 300 characters, it is the most complex story in Chinese fiction. Mixing influences of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, parts of the story seem dreamlike, while others are solid reflections of upper-class life in late imperial China. In Chapter 14, for instance, Bao Yu is tested by his father on the composition of antithetical couplets to describe the scenes in the Park of Delightful Vision located on the family grounds.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, a number of women wrote long prosimetric works called chantefables (tanci). The most famous author was Chen Duansheng, who began writing what would become a 600,000-word work when she was only 16. The story concerns Meng Lijun, a young woman from a rich family in Yunnan province. In order to escape a horrible, arranged marriage, the young woman dresses as a young man and runs away from home. Later, she passes all the imperial examinations and becomes prime minister. Since the author died before completing the story, it was finished by another woman a number of years later. In the end, the heroine Meng Lijun is discovered by the emperor, but later pardoned and marries a handsome elite young man. In one of the most interesting passages, Meng Lijun, as the prime-minister, was arranged to marry a young woman, who turned out to be her former maidservant. They recognized each other and continued the ruse.

Drama became established in the popular culture of China during the Yuan dynasty under Mongol rule (the Mongols loved opera!). By the 15th century southern forms of opera like Kunqu were flourishing and would later influence the northern form of opera that in the early 19th century became known as Beijing (Peking) opera. Many opera scripts were published and read as literature. One of the most famous authors was Guan Hanqing of the 16th century. Many operas are versions of stories told in fiction and by professional storytellers. Thus, in traditional China, a story might be told or performed in many mediums—and today those mediums have grown to include radio, film, and television. Some opera performances were very long. In 2001, a 200-hour-long version of the classic opera “Peony Pavilion” (Mudan ting) was performed in New York city.

|

|

Modern Literature

Modern Chinese literature dates to the revolutionary period of the early 20th century. Influenced by modern European, Russian, American, and Japanese writings, Chinese intellectuals began experimenting with Western-style short stories, novels, and the new “free verse” poetry. Like the Modernist movement in Western art and literature that began in the late 19th century, Chinese intellectual and popular culture changed rapidly throughout the 1920s and through the war-torn decades of the 1930s and 1940s.

Important writers and poets emerged during the intellectual awakening of the May Fourth Movement that began in 1919 and the consequent New Culture Movement. Among the new voices were the short story writers Lu Xun and Ding Ling; the poets Guo Moruo and Bing Xin; the novelists Ba Jin, Mao Dun, and Lao She; and the playwrights Cao Yu and Tian Han.

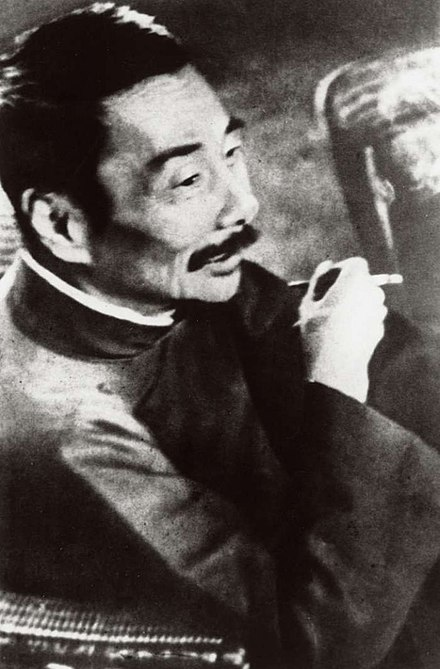

Lu Xun is credited as being a major founder of modern Chinese literature and his works did much to arouse the moral and patriotic feelings of young Chinese in the May Fourth period.

His most famous work, “The True Story of Ah-Q,” concerns a clueless young farmer who rationalizes away all of his sufferings brought on by life in an unfair and backward social system. In Ah-Q, Lu Xun presented a character that symbolized China’s reluctance to wake up and confront a rapidly changing world.

Ding Ling (1904-1986)

Ding Ling (1904-1986) was a progressive writer of the New Culture Movement. A key early work is the short story “Diary of Miss Sophie,” published in 1927. She challenged male-centric beliefs in the government structure of New China, for which she suffered in the Anti-Rightist Movement of the 1950s.

| Major Ethnic Minority Writers of the 20th and 21st Centuries | |

Novelist Alai (1959-) of Tibetan and Hui background. His novel Red Poppies, about life in Tibetan communities before 1949, has been translated into English by Howard Goldblatt and Li-chun Lin. |

Jidi Majia (1961-) is a native of southern Sichuan. His works have been published in numerous languages. He has been instrumental in bringing Chinese ethnic minority poetry onto the world stage, beginning in the 1980s. |

Poet Aku Wuwu (1964-) from Sichuan province, writes poetry in both Nuosu Yi language and Standard Chinese. He has visited The Ohio State University several times since 2005. His most famous poem, concerning cultural revival, is “Calling Back the Soul of Zhyge Alu.” |

Huo Da (1945-) is a member of the Hui ethnic group in China, she has written a number of lengthy novels on the Muslim experience in China. |

| Major Woman Writers of the 20th and 21st Centuries | |

Zhai Yongming (1955-) ground-breaking poet and essayist and author of the 1984 poetry collection Woman and the 1993 poem “Song of the Café,” has been compared to American poet Sylvia Plath, and often writes on themes of gender and darkness. The free-spirited writer presently runs a popular book and wine pub in Chengdu. Her work has been translated into English by Andrea Lingenfelter. |

San Mao (1943-1991) was an extremely popular travel writer, novelist and autobiographer, who published a best-selling work called Stories of the Sahara in 1976, based on her real life experiences in North Africa with her Spanish husband Jose. San Mao’s family was from Zhejiang province, but immigrated to Taiwan during the Civil War. She was a gifted but non-typical and rebellious student. She lived abroad in several European countries and many of her rich experiences were recorded in her riveting, popular books. |

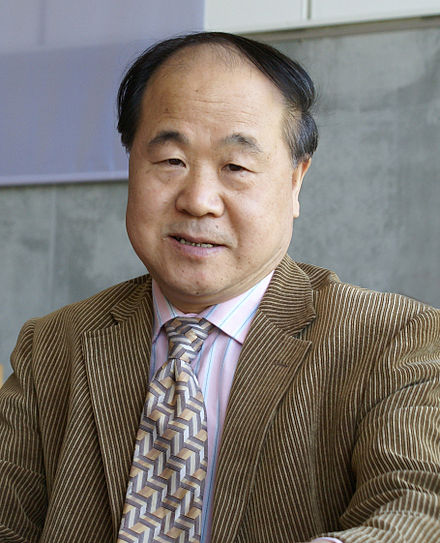

Mo Yan (1955-) is the 2012 Nobel prize winning author of Red Sorghum, made into the award-winning film Red Sorghum in 2005.

|

|

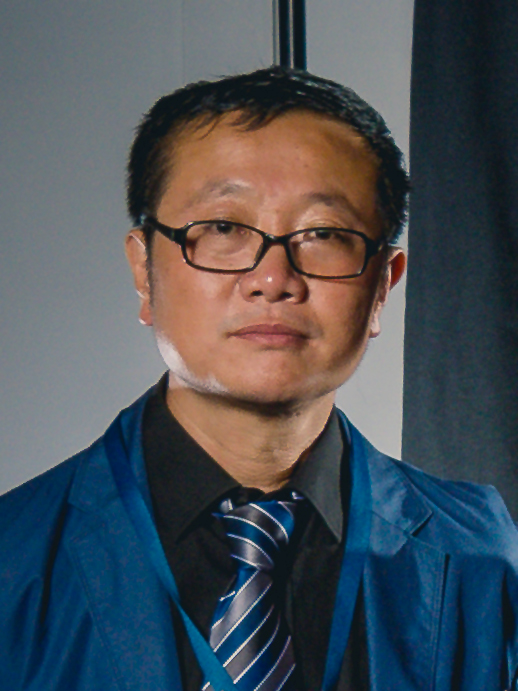

AI (artificial intelligence) science fiction, which also often include environmental themes, has become popular in China. Liu Cixin’s “Wandering Earth,” set in a future when the sun is dying out and a group of humans attempts to survive the catastrophe with various AI strategies. Such works can sometimes be considered as a kind of “soft power” in the promotion of China’s interests in becoming an AI leader in the age of “China Dream,” much in the same way as science fiction helped create public interest in the USA space program in the 1950s and 1960s with authors like Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein, and Isacc Asimov. |

|

LITERATURE OF KOREA

Introduction

The study of Korean literature is a rather new field, dating to the post World War II period. To begin with, the question must be asked, “What is Korean literature?” While the answer might seem simple (“It is the literature written by Koreans!”), there has been some disagreement over the question. This is because traditional Korean literature can be divided into four classes:

1. Literature written in Hanmun : This is the earliest literature written by Koreans. It is written using “Chinese” characters (Hanmun). Hanmun was used by Korean scholar-officials up to the early 20th century. One example of a Hansi (Chinese style poem) written in Hanmun was composed by the poet scholar Yi Gyubo (1168-1241).

2. Literature written in systems using “Chinese” characters to represent Korean sounds or meanings. That is, instead of using Chinese characters for the meaning, they are used for their sound value to sound out Korean words. The best known was called Idu. This system was in use by about the 7th century but was never popular. Only a few poems survive. It is a very awkward system, but its development shows that the Koreans were searching for a writing system that reflected the sounds of their language.

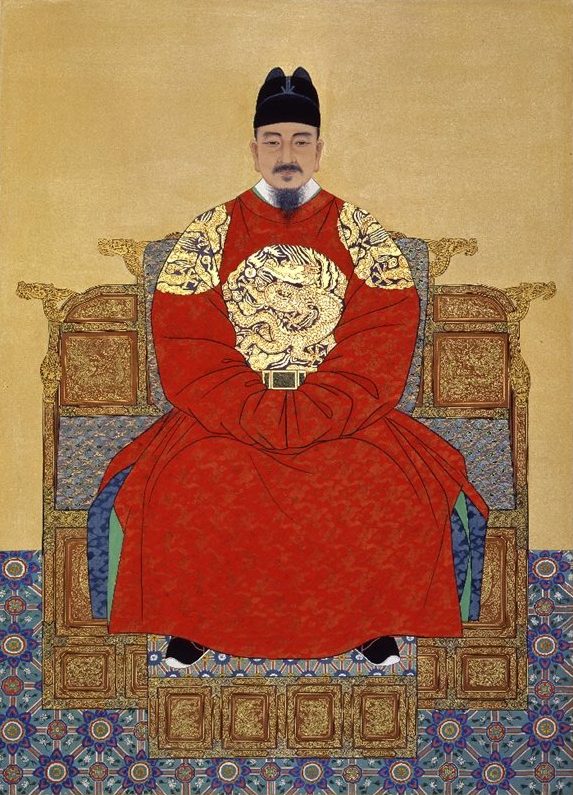

3. Hangul: Literature in this category was written after the 1450s, when King Sejong introduced a new writing system called Hangul, which solved the problem of having an easy to learn writing system that reflected the sounds of Korean language. Similar to an alphabet, the Hangul is considered as a “syllabary,” in that it reflects actual sounds of a language.

4. Mixed systems: After the 15th century some literature was written in a mixture of Hanmun (Chinese characters) and Hangul (the Korean syllabary). Most of this literature was popular literature, since scholars preferred the Hanmun system.

Pre-Modern Korean Literature

Most pre-modern works of literature were written in Hanmun. Most of such writings were poems. For example, Yi Gyubo (1168-1241) left behind at least 1,500 poems written in Hanmun. Early creation stories and histories were also written in Hanmun, including the Samguk sagi (Annals of the Three Kingdoms) and Samguk yusa (Accounts of the Three Kingdoms).

Although these works were about the Three Kingdoms period (37 BCE-668 CE), they were written later in the Goryeo dynasty (918-1392 CE) and include myths, legends, and songs.

Some examples of poems written in Idu and similar systems using Chinese characters for sound value have been preserved in such histories. About 25 such poems called hyangga survive from the Silla period, and about two-dozen poems called gayo from the Goryeo period. Among the latter poems is a famous one preserved in the Samguk sagi, “Song of Cheoyong,” which is about the 7th son of the Dragon King. Scholars still debate its meaning. Some say that although the Son of the Dragon King is a supernatural character (the king of dragons is said to have a palace in the sea), the characters in the song represent actual people. Others say there is some relation to the worship of the smallpox god. Nevertheless, the poem is a glimpse of a society that existed on the Korean peninsula over 1,000 years ago.

Beginning in the late Koryo period, and gaining wide popularity in the Joseon dynasty, was a style of lyric poetry called sijo. Sijo were written in Hangul, or in a mixture of Hangul and Chinese characters. About 4,000 sijo survive, most written by yangban officials. Many were written on the theme of loyalty to king and country. About 92, however, were written by female entertainers known as kisaeng (similar to the geisha of Japan and teahouse entertainers in China). Kisaeng were trained to read and compose poetry, play musical instruments, and dance. There was even a special government bureau to oversee the kisaeng, who were allowed more freedom outside the home than normal women. In the traditional Confucian society, however, kisaeng were considered lower-class, since their profession violated social codes of female chastity.

The best-known of the Korean kisaeng poets is Hwang Jini (c. 1506-1544 CE), who was born into an upper-class family but later became an entertainer. One of the many legends about her centers on how she became a kisaeng. According to the story, a young man had somehow fallen in love with young Hwang Jini. Since it was impossible to meet her, he gradually developed “love sickness.” One day the young man suddenly took ill and died. As his funeral procession passed Hwang’s manor, it suddenly became so heavy that it could not be carried. Hearing of this, Hwang gave one of her garments to a maid and told her to drape it on the casket. Once covered with Hwang’s garment, the casket grew light and was carried away. But because she had allowed a personal garment to be placed in association with a young man, Hwang had violated the Confucian rules of female chastity. Her options were now limited, as she was ineligible for a proper arranged marriage. She could become a Buddhist nun, commit suicide, or become a female entertainer. Choosing the last option, she became famous for her intelligence and beauty.

Her surviving poems are sensitive, sensuous, and sometimes playful. One of her poems, “Blue Stream” is regarded as a masterpiece. It is read as a challenge to a famous Confucian worthy named Blue Stream (Byeokgyesu in Korean), who claimed he could resist the charms of any woman.

Literary works by women appeared in Hangul and mixed systems after the 15th century. Aside from kisaeng poets like Hwang Jini, upper class women of the king’s court also contributed to women’s literature (amgul). The best examples are diaries written by court women. Titles in this “Palace literature” include Diary of the Year of the Black Ox, 1613 (Gyechug ilgi); Life of Queen Inhyeon (Inhyeon wanghu jeon), by Queen Inhyeon; and Records Made in Distress (also translated as Memoirs of a Korean Queen, or Hanjungnok), by Lady Hong (Hyegyeong), wife of Crown Prince Sado (who died in 1762).

The third text recounts the story of Lady Hong, who was married into the king’s family at age ten. Her diary recalls the kind treatment she received from court ladies until her actual marriage at age 16, the birth of children, epidemics, and her relationship with her husband and the king. In many ways a tragedy, her story exemplifies the Korean literary aesthetic of han, or “living with loss.” A major theme is explaining the events leading up to the execution of her insane husband, who was killed by his own father the king. In his plunge into insanity, the crown prince had killed several servants for no reason and otherwise behaved badly. The king ordered that he be smothered to death in a large grain box (because it was bad luck to shed the blood of royalty). Lady Hong’s father was ordered to supply the box. In order to clear her father’s name in the official accounts, Lady Hong wrote her version of events after she reached age 70.

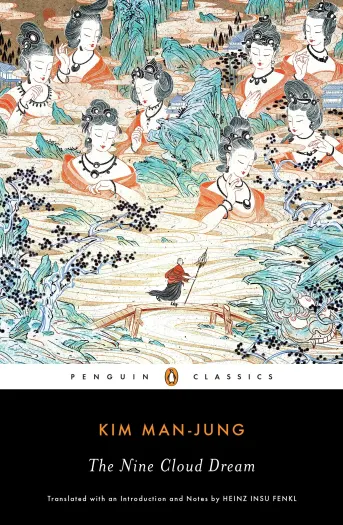

Several popular novels (soseol), similar to Chinese xiaoshuo vernacular fiction, were written between the 16th and 19th centuries. Among these is a tale of a Buddhist adept on a search for enlightenment, who encounters eight young women while crossing a bridge and is subsequently sent on a twisting path of karmic retribution. Entitled The Nine Cloud Dream (Kuunmong), it was written in Chinese by Confucian scholar Kim Man-jung in the 17th century.

|

|

| With the growing popularity of Korean pop culture have come English translations of some of its most well-known fiction, including these titles above. | |

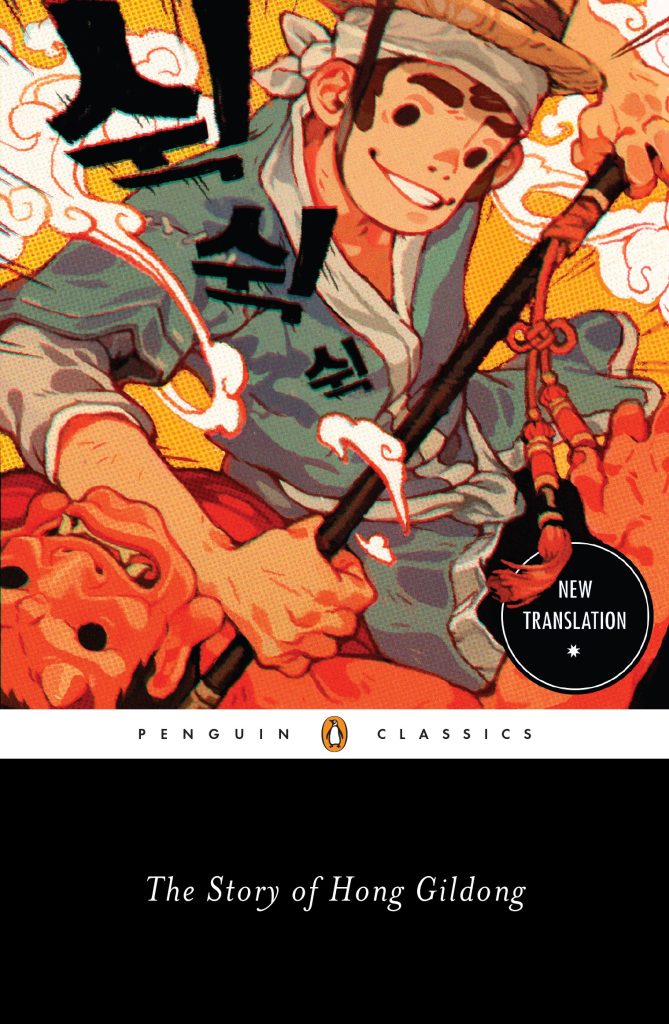

The famous Tale of Hong Gildong (Hong Gildong jeon) about a band of outlaws is similar in some ways to the Chinese Outlaws of the Marsh. An interesting twist is that many of the characters are illegitimate sons from middle or upper class families.

In some cases, Korean males had affairs with household servants or took concubines. The resultant children would be raised as part of the family though their status never equaled that of the “official” children. Sons from such unions were at a social disadvantage in terms of education and position. It is even more interesting that the author of the novel was an illegitimate son himself.

Another important type of literature from the 18th and 19th centuries is the prosimetric form known as pansori.

In this form, prose and poetry are intermixed. Both printed texts (in Hangul and mixed systems) and oral performances were available to audiences. Among the most famous stories are The Story of the Faithful Wife, Chunhyang and The Story of Sim Chong. Both stories are strongly influenced by Neo-Confucian morality and virtues. The Sim Chong story concerns a 15-year-old girl who sells herself to a band of sailors as a sacrifice to the sea god in order to restore her blind father’s sight.

The Chunhyang story is the most famous love story in Korea. Chun-hyang is the 15-year-old daughter of a liaison between a yangban scholar-official and a kisaeng entertainer. While swinging on a swing in her courtyard one day, she is spied by young Yi Myong-ryong, a young man in an official’s family. Yi later arranges a secret rendezvous with Chun-hyang, and the teens eventually hold a secret marriage—followed by a night of energetic lovemaking. Soon after, young Yi must leave for the capital to sit for the civil service examinations. Chun-hyang pledges her loyalty to him. While he is away, a new governor is assigned to the province of Namwon.

Hearing of Chunhyang’s beauty, he summons her as a kisaeng and concubine. She claims that she is a married woman, and the daughter of a yangban aristocrat. The governor throws her in jail when she refuses to be intimate with him. Meanwhile, Yi passes the examinations and is awarded the position of a civil inspector. Disguised as a poor, failed scholar, he meets with Chunhyang’s mother and secretly visits Chunhyang (who is wearing a heavy wooden collar) in prison. The next day Yi crashes the governor’s birthday party and demands to be fed, since he too is an aristocrat by birth. At the banquet, he writes a sijo poem hinting at the greed and abuses perpetrated by local officials at the people’s expense. Suddenly, a band of imperial troops rush in and scatter the corrupt officials. Changing into his finest robes, Yi reveals himself as an imperial inspector and summons Chunhyang to him. Chunhyang refuses to submit to this new official and repeats her pledge of loyal chastity. With this public declaration, it is obvious to all that Chun-hyang, whose social position is ambiguous because of her mother’s status, is indeed a loyal wife. Finally, the two can officially marry. In a park in Namwon not far from her home there is still a shrine to Chunhyang, and the splendid pavilion where Yi Myong-ryong stood when he first saw her on the swing.

Modern Korean Literature

Up until the early 20th century, Hanmun was still used by Korean scholar-officials. Beginning in the late 19th century nationalistic feelings against Japanese and other foreign encroachment helped fuel a National Language Movement in which the Hangul syllabary was promoted as being more suitable for modern purposes; it eventually became the mainstream written language. Translated portions of the Judeo-Christian Bible, Western-style newspapers, and new-style novels (sinsoseol) were among the first modern works in Hangul available to a mass market.

Various literary trends developed during the Japanese occupation and the period of division after 1945. One of these trends was the “education movement,” which saw the increased publication of stories meant to educate the masses. Such stories included biographies of heroes and satirical novels. Another movement was the “discovery of the self,” which emerged during the Japanese occupation of the 1910s to 1940s, and it was spearheaded by author and independence activist Yi Kwangsu (1892–1950). He famously argued in an essay on the value of literature that literature is “art that expresses elements of human feeling using words.” His novel Heartless (Mujeong; 1917) about the changing lives of two young Koreans in the modern age is an early example of this merging of individual consciousness with national spirit.

Since the democracy movement of the 1980s, a lively literary and drama scene has emerged in South Korea, while North Korean artists still work within strict confines of the government. Short stories and poetry are popular in South Korea, and South Korean film has recently taken increasing space on the world stage. Contemporary writers include Park Wan-suh, Ko Un, Hwang Sok-young, O Jeonghui, Choe Yun, Kim Young-ha, and many others.

Some major Korean authors from the Post-World War II Era |

|

Park Wan-suh (1931-2011) was a highly celebrated and award-winning author of many novels. She wrote on the trauma of the Korean War, critiques of the middle class and patriarchal society. Her novel The Dream Incubator (1993) is one famous novel about a middle-class woman who is forced to have several abortions until she bears a male son. |

Ko Un (1933–) is a poet who was a major figure in the campaign for democracy in Korea and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. His enormous oeuvre contains more than 150 volumes of poetry, essays, novels, translations, and so on. One of his works of poetry is a seven-volume epic about the Korean independence movement called Paektu Mountain (published between 1987–94). |

Kim Jiha (1943-) was an “underground” activist poet in the 1970s. Sentenced to death at least twice, he was later freed as times changed and continues to write today. |

Hwang Sok-young (1943–) is a novelist who was involved in the Vietnam War and whose works reflect on the political and personal destruction wrought by the conflict. His work is said to explore homelessness in the Korean psyche. |

O Jeonghui (1947–) is a short story and novel writer whose award-winning works reflect on the entrapment of women in traditional family life. Her works are often described as tragic and depressing. |

Ch’oe Yun (1953–) is a professor of French literature whose works deal with events surrounding the Gwangju Uprising of 1980. Her novel There a Petal Silently Falls (1988) brought her to national attention and she has since been called one of Korea’s most important contemporary writers. |

Shin Kyung-sook (1963-) is an author of the “386 Generation,” a group of politically active writers who are known for their sympathy for North Korea and criticism of the U.S. She is famous for the acclaimed novel Please Look after Mom (2008), which sold over 2 million copies in South Korea. Suggestions of plagiarism in some of her works have marred her acclaim. |

Kim Young-ha (1968–) is a former drama school professor and radio show host who has been writing and translating English novels since 2008. His novels are often considered pioneering works in urban fiction, and the topics he covers are often underrepresented in Korean fiction, such as computer games, homosexuality, and narcissism. Many of his works have been adapted as movies and musicals. |

LITERATURE OF JAPAN

The literature of Japan begins with the introduction of Chinese writing by the 6th century CE. Legend says that Prince Shotoku (d. 622 CE), an advocate of Buddhism and Chinese culture, had a scribe from the kingdom of Paekche on the Korean peninsula. Although Chinese and Japanese are very different languages, written Chinese was the only writing system available to the Japanese. Like the Koreans, Japanese scholars learned classical Chinese and continued using it (with some modifications in meaning and pronunciation) into the 20th century. Some Japanese still write Chinese-style poems today. About 1800 Chinese-derived characters (kanji) are still used in popular Japanese writing today, mixed with the Japanese phonetic syllabaries developed in the 8th century.

The first extant Japanese literary works were myths and legends recorded in two early prose works from the early 8th century called Kojiki (712 CE) and Nihonshoki (720 CE). The first poetry collection from the mid-8th century is Manyoshu, or Collection of 10,000 Leaves. Themes in the poems included nature, the seasons, and human emotion. In 905 CE, Kokinshu, or Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems was assembled. This collection was written in the new syllabaries (kana) and the kanji characters. The style of poems were known as waka and used a format with a fixed number of syllables in each line: 5-7-5-7-7.

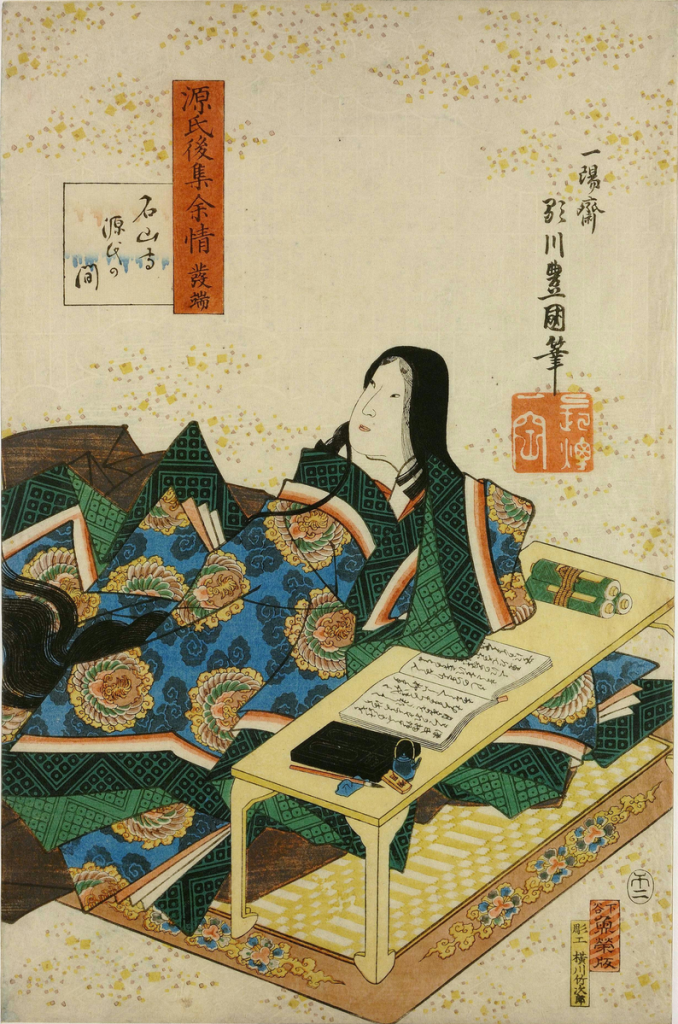

During the Heian Period (794-1193 CE), the kana syllabary came into common use, and was especially favored by ladies of the court. The world’s first novel, Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari), was written by Murasaki Shikibu about 1000 CE. The text is a complicated political and romantic work, involving almost 1000 characters and spans several generations. Great detail about the complex dynamics of social etiquette is provided, as well as evocative descriptions of subtle feeling. The main characters often communicate by letter, rather than by direct speech.

Another important work is The Pillow Book, by another court lady named Sei Shonagon. More light-hearted than the Tale of Genji, the work consists of essays on court life, personal diaries, and lists of things of interest to the author. These and other works by women give a wonderful picture of life in the refined world of Heian aristocrats.

The tone and theme of Japanese literature gradually changed as the Japanese abandoned their experiment with a Chinese-style government. The Japanese feudal system emerged in a sort of Middle Ages, with the constant martial strife among competing domains between the 13th and early 17th century leaving an imprint on literary works such as The Tale of Heike (Heike monogatari). Written as if performed by a lute (biwa) storyteller, Heike dates to around 1371 and recounts battles between the Taira and Minamoto families. It includes many scenes of great beauty in conjunction with death on the battlefield. The dominant aesthetic of many such writings is the melancholic feeling of sabi.

A much different work from the same period, however, is An Account of My Hut (Hojoki), written by a 13th century hermit, Kano no Chomei. Celebrating reclusive rural life, the work is something like the 19th century American work Walden, by Henry David Thoreau. During this period Zen Buddhism began to have a strong impact on many aspects of Japanese life, especially among the upper-class samurai.

|

|

A form of drama called Noh (or No), that had folk origins, embodied many of the teachings of Zen. A playwright named Zeami composed over 100 Noh plays, and stressed that actors must demonstrate a cultivation of the oneness between mind and body (“empty mind/heart”) when performing the highly stylized, almost “slow motion” Noh dance steps and movements. Noh plays drew on legends and stories from both Japan and China. The Noh play called “Feathered Mantle” (Hagaromo in Japanese) is a famous play based on an ancient folk tale common to North Asian cultures. It tells of a swan maiden who descends to earth in human form. She loses her feathered cloak to a curious fisherman, who demands she dance before allowing her to return to the sky. The slow, elegant dance is a high point of the play.

During the Tokugawa Period, Japan enjoyed nearly 250 years of relative peace and isolation. As the urban centers and middle class grew, popular entertainments and literature flourished. While the samurai still enjoyed Noh, new styles of drama with more mass appeal appeared, especially kabuki.

A form of brief, Zen-inspired nature poetry, called haiku, was popularized by poets such as Basho (1644-94), who wrote a famous poem about a frog jumping into an old pond. In such fleeting and mundane occurrences, the haiku poets sought to capture insight into and appreciation of existence. The structure of these poems is three 5-7-5 syllabic lines.

During the Tokugawa period popular novels gained great popularity, along with collections of weird tales on ghosts, goblins, and human-eating monsters called oni. Vividly described characters from the merchant class, samurai, and denizens of the “floating world” (pleasure districts) of Osaka and Edo (Tokyo) were depicted in the novels of this period. Among the most famous authors was Ihara Saikaku (whose real name was probably Togo Hirayama) (1642-93), who wrote The Life of an Amorous Woman.

By the mid-19th century, Western cultural influences began to have an unavoidable impact on Japanese society. Along with selective borrowings in the area of economics, industry, politics, and military technology, the Japanese also imported works of foreign literature which, once translated into Japanese, influenced succeeding generations of Japanese, as well as the Chinese and Korean students, like Lu Xun of China, who studied in Japan in the early 20th century.

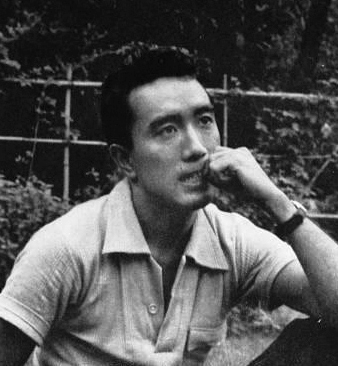

Innovative Japanese writers such as Natsume Soseki (1876-1916), author of Heart (Kokoro) and Futabatei Shimei (1864-1904), author of Drifting Clouds (Ukigumo), were among the new generation of novelists who combined Western and traditional Japanese techniques in the writing of author-centered “I-novels,” a naturalistic confessional genre. In the popular realm, detective stories influenced by Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and stories of common people’s struggles in the newly industrialized landscape became popular in the early decades of the 20th century. In the post-World War II era (1945-present), among the new breed of authors that emerged were a number influenced by the demoralization of Japan’s defeat, post-War Existentialist philosophy, and Absurdist literature in Europe. Foremost among these authors was the ultra-Nationalist Yukio Mishima (1925-1970).

Yukio Mishima explored the darker sides of the human psyche and startled the word by his public enactment of seppuku suicide.

Mishima drew attention in Japan and the West for probing his darker sides in Confessions of a Mask (Kamen no Kokuhaku; 1949) and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (Kinkakuji; 1956) and his dramatic public suicide by sword in 1970. Abe Kobo (1924-1993) authored the Absurdist novel Woman in the Dunes (Suna no Onna) in 1962, about an entomologist who becomes entrapped in the bizarre world of a woman living inside a huge pit in a shifting sand dune.

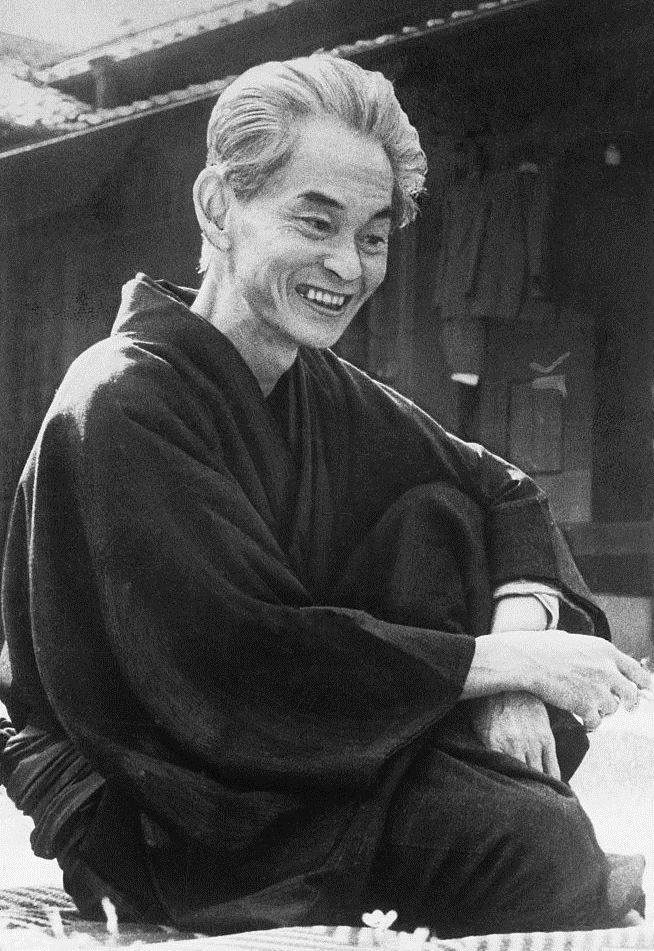

Two Nobel laureates in literature also emerged in the Post-War era. Kawabata Yasunari (1899-1972) received the award in 1968. His works include Snow Country (Yuki-guni), the story of a middle-aged writer and his relationship with a geisha entertainer past her prime. In 1994, the award went to Kenzaburo Oe (1935-) for works that include Silent Cry (Manen Gannen no Futtobunen) about a writer’s relationship with his brain-damaged child. Ariyoshi Sawako (1931-1984) represented another voice in Japanese letters with her 1967 novel The Doctor’s Wife about an 18th century doctor who develops anesthesia by experimenting on his mother and wife. More recently, the works of Banana Yoshimoto (1965-), whose works include novels on life of young women in modern Japan like Kitchen (1987), have found foreign audiences in translation.

|

|

|

|

Selected Sources

Chinese

Anonymous. “Plop Fall the Plums.” Translated by Arthur Waley. In Cyril Birch, ed. Anthology of Chinese Literature: From early times to the fourteenth century. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965, Volume 1, p. 7.

Anonymous. “Lies a Dead Deer.” Translated by Ezra Pound. In Cyril Birch, ed. Anthology of Chinese Literature: From early times to the fourteenth century. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965, Volume 1, p. 8.

Anonymous. “The Ballad of Mulan.” Translated by Arthur Waley. In Victor H. Mair, ed. The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 474-476.

Bai Juyi. “Song of Eternal Sorrow.” Translated by Witter Bynner. In Cyril Birch, ed. Anthology of Chinese Literature: From early times to the fourteenth century. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965, Volume 1, p. 267-268.

Li Bai. “Still Night Thoughts.” Translated by Burton Watson. In Victor H. Mair, ed. The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 204.

Du Fu. “Spring View.” Translated by Gary Snyder. In Victor H. Mair, ed. The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 208.

Xue Tao, “Cicadas. ”Translated by Jeanne Larsen. In Brocade River Poems: Selected Works of the Tang Dynasty Courtesan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987, p. 4.

Li Qingzhao. “Spring at Wuling.” Translated by C.H. Kwock and Vincent McHugh. In Cyril Birch, ed. Anthology of Chinese Literature: From early times to the fourteenth century. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965, Volume 1, p. 361-362.

Shi Nai’an and Luo Guanzhong. Outlaws of the Marsh. Translated by Sidney Shapiro. Beijing: Foreign Language Press and Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1981, Volume 1, p. 163-170.

Wu Cheng’en. Journey to the West. Translated by W.J.F. Jenner. Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1982, Volume 1, p. 508-524.

Cao Xueqin. The Dream of The Red Chamber. Translated by Florence and Isabel McHugh. New York; Pantheon Books Inc., 1958, p. 123-134.

Anonymous. “Love Reincarnate.” In Mark Bender, “Regional Literatures.” In Victor H. Mair, ed. The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011, p. 1021-1022.

Lu Xun The True Story of Ah Q. Translated by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang. In Lu Xun: Selected Works. Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1980, Volume 1, 102-155.

Gao Xingjian. Soul Mountain. Translated by Mabel Lee. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2000, p. 10-15.

Korean

Anonymous. “Samguk yusa.” In Kichung Kim. An Introduction to Classical Korean Literature: From Hyangga to P’ansori. Armonk, N. Y.: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 1996, p. 68.

Anonymous. “Song of Cho’yong.” In Peter H. Lee, ed. Anthology of Korean Literature: From Early Times to the Nineteenth Century. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1981, p. 21.

Hwang Chini. “Blue Stream.” Translated by Constantine Contogenis and Wolhee Choe. In Songs of the Kisaengs: Courtesan Poetry of the Last Korean Dynasty. Rochester, N.Y.: BOA Editions, Ltd., 1997, p. 27.

Lady Hong. Memoirs of a Korean Queen. Translated by Choe-Wall Yang-hi. Boston: KPI Limited, 1985, p. 72-74.

Ho Kyun. “The Tale of Hong Kiltong.” Translated by Marshall R. Pihl. In Peter H. Lee, ed. Anthology of Korean Literature: From Early Times to the Nineteenth Century. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1981, 119.

“The Song of a Faithful Wife, Chun-hyang.” In Peter H. Lee, ed. Anthology of Korean Literature: From Early Times to the Nineteenth Century. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1981, p. 271-284.

Japanese

Anonymous. “Love’s complaint.” Translated by The Japanese Classics Translation Committee. In Donald Keene, ed. Anthology of Japanese Literature: from the earliest era to the mid-nineteenth century. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1955, p. 42-43.

Anonymous. “An elegy on the impermanence of human life.” Translated by The Japanese Classics Translation Committee. In Donald Keene, ed. Anthology of Japanese Literature: from the earliest era to the mid-nineteenth century. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1955, p. 45-46.

Anonymous. Kokinshu. Translated by Donald Keene. In Donald Keene, ed. Anthology of Japanese Literature: from the earliest era to the mid-nineteenth century. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1955, p. 79-80.

Murasaki Shikibu. The Tale of Genji. Translated by Royall Tyler. New York: Viking, 2001, p. 154-161.

Anonymous. “Sanemori.” Chapter in theT ale of Heike. Translated by Royall Tyler. New York: Penguin Classics, 2012 pp. 369-371.

“The Feather Mantle.” Translated by Royall Tyler. In Royall Tyler, ed. Japanese No Dramas. London: Penguin Books, 1992, pp. 100-107.

Matsuo Basho. “A Frog Poem.” Translated by Mark Bender.

Yoshimato Banana. Kitchen. Translated by Megan Backus. New York: Washington Square Press, 1993, p. 23-30.

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

- Literature of China

- Literature of Japanese

- Literature of Korea