8 Module 7: Performance In East Asia

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities. In this module, some of the playlist’s content can also be found within the text for easy access.

INTRODUCTION

The performing arts have a very long history in East Asia, a history that crosses many cultural and geographical barriers. Folk songs, folk stories, professional storytelling (which is often combined with music), theater, and epic singing are among the major types of performance traditions associated with various cultural groups in East Asia.

We will first trace the history of major traditional performance styles in the region and examine several historic traditions from each region that are still practiced in East Asia today. Some of the traditions are widely known today, while others have only a local following. Many performance traditions grew up over many centuries in East Asia. Certain types of traditional performances are still carried on today, though new contexts (situations) have emerged in which they are performed.

Folksongs and folk stories seem to date to prehistoric times, with the earliest records dating to the 5th century BCE, in the Book of Songs (Shijing) from China. The songs compiled in the Book of Songs, China’s earliest collection of verses and one of the Confucian classics, are believed to be folk songs that were collected from various parts of northern China and polished by scholars. By examining the songs of local regions of China, the early rulers could gauge the mood of their subjects, or the virtues or misdeeds of rulers and citizens in neighboring kingdoms. Later in the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), the government established a Music Bureau in which the various song and music from around China were studied, including that of the rural folk.

Folksongs in many regional styles, dialects, and languages were widely performed throughout the rural areas of East Asia well into the 20th century, though the number of people able to sing them continues to decline. Their themes range from courtship, to cradle songs, songs of welcome and departure, songs for guests, songs of the seasons, and many others. Orally told stories are still popular in all three countries, though many people learn traditional tales as much by watching television and cinematic adaptations as by hearing them on their grandparents’ knees.

By the 1st century CE, Buddhism was beginning to seep into China over the deserts and mountains of the Silk Road to the north and from Southeast Asia into China’s southwest. Many styles and components of performance, including music, storytelling, drama, and musical instruments eventually entered on these routes, often originating in far-off places like India, Central Asia, and the Middle East.

By the great Tang dynasty (618-906 CE), a special style of storytelling involving alternating passages of speaking and singing became a vehicle for spreading the teachings of the Buddha in story form. Early in the 20th century, Western explorers found a cache of these prosimetric texts at the Buddhist cave complex at Dunhuang in northern China. Sealed for over one thousand years, the caves contained a vast store of written performance texts in Chinese, Sanskrit, Tibetan, and various other languages spoken on the Silk Road. These so-called “transformation texts” include both Buddhist tales and also secular tales that seem to have been performed for entertainment rather than religious enlightenment. As a whole, this cache constitutes the greatest hoard of ancient performance-related texts found in East Asia to date.

This prosimetric style of storytelling would later influence many forms of orally delivered narratives in China, Korea, and Japan. Professional storytellers, who told stories to marketplaces crowds, as well as to guests at indoor teahouses or actual story houses, emerged in all three countries by the 11th century, and several traditions performed today can be traced back directly at least as early as the 18th century. Many stylistic tropes from the oral storytelling tradition have been used in written fiction since at least the Ming dynasty in China, as well as in Korea, and Japan. Some of these traditions still survive today in local storytelling traditions such as “telling scriptures” and Suzhou chantefable in China; one-man opera in Korea; and lute-lyrics in Japan.

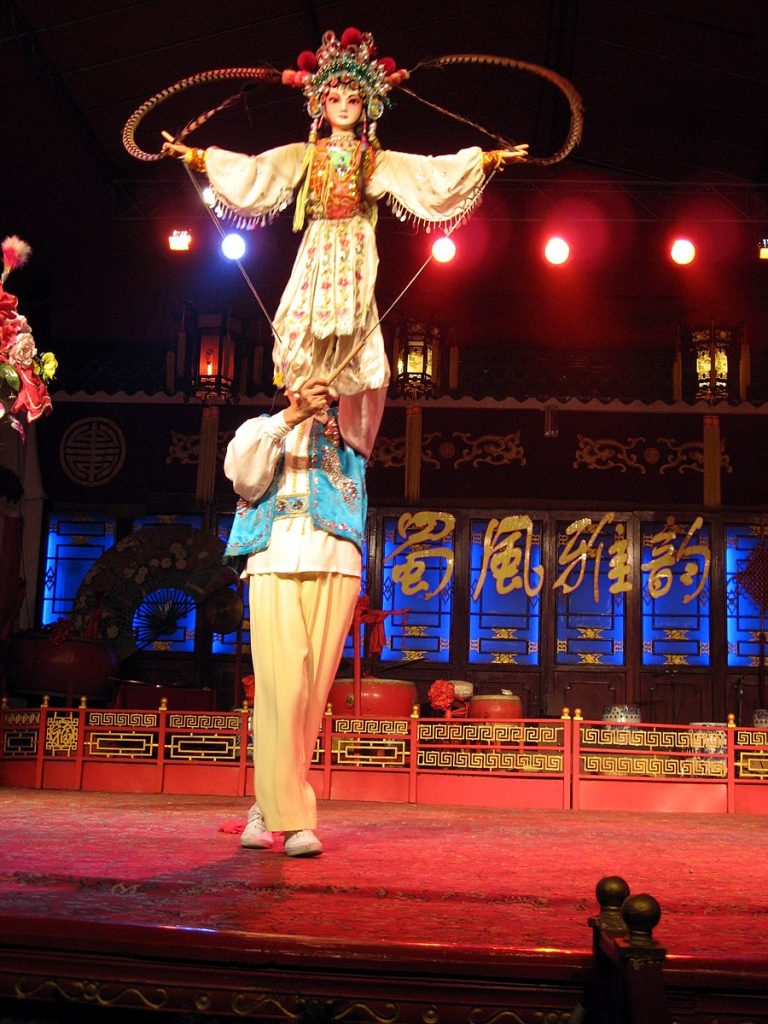

Traditions of drama also have deep roots. Masked opera forms such as Noh in Japan, Talchum in Korea, and Nuo in southern China, all feature the use of carved wooden masks to represent certain role or character types. All three forms also feature the interaction of gods and humans and are delivered in a mixture of speaking and singing. They are all also rooted in the traditions of life in agricultural villages, although some forms (Noh drama in Japan) later developed into art forms that served the tastes of the urban elite. During Mongol rule in the 12th century, drama became immensely popular in China and many Han Chinese literary men began producing operatic plays. Kunqu opera and later Beijing (Peking) opera descended from forms of theater in this period. In these Chinese opera traditions, rather than wearing wooden masks, actors painted their faces, a custom that may be rooted in local theaters in India. In Japan, actors in the opulent kabuki theater also employ vivid face paint to complement their elaborate costumes.

Performance traditions in contemporary East Asia reflect both the traditions of local cultural areas and recent influences from the West, ranging from classical music to American hip-hop. While pop music dominates many of the airwaves and television screens in East Asia today, traditional performances are held regularly in performance halls, special story or opera houses, and festival events all over the region, sometimes with government support. Local radio and television stations devote special slots to storytelling and traditional opera and many traditional forms are featured in televised variety shows during national celebrations. Many museums and theme parks also often feature traditional artists and performances.

Although many of younger people in contemporary East Asia are unfamiliar with traditional forms, devoted fans in the older age ranks help maintain an interest in many of them. As living forms, however, it is necessary to recruit and train younger people to keep the traditions alive. Training in these arts often takes many years and only the most devoted students succeed in carrying on these unique ways of artistic communication rooted so deeply in the past.

PERFORMANCE TRADITIONS IN CHINA

Overview

There are hundreds of performance traditions in China. Most are local traditions, though some have a following in larger regional areas. Beijing opera is more or less regarded as a national tradition, though its “hometown” is the capital of China, Beijing. Among the Han Chinese, performance traditions are folk songs, stories, and dance; local operas; local styles of professional storytelling; ritual music and dance; “classical” Chinese court and ensemble music; and all sorts of globalized pop and Western-inspired classical music and theater. Minority traditions include many of these styles, as well as epic traditions such as the heroic tales of King Gesar and Janggar, performed by Tibetan and Mongol epic singers. Since most traditional styles are performed in local topolects (that is, languages particular to particular localities), lyrics are often unintelligible to speakers of other kinds of Chinese or minority languages.

In this section, we will examine several traditions representing several styles of performance. Many of them are similar to traditions in other parts of the country but have a recognizable local style. Others are known only locally. In some cases, only older persons in a community may take interest or participate in the traditions. If younger people continue to age and “grow into” these traditions, they will survive. On the other hand, competition from pop music and film provide strong, and sometimes overwhelming, competition for the traditional styles of performance. In some cases, traditional and contemporary forms have merged, to create “fusion” performances. Such innovations have recently appeared in the tourist trade, televised variety shows, and experimental theater. Since the early 2000s, an increasing number of performance traditions have been given the status of “Intangible Cultural Heritage” (ICH) by the United Nations’ UNESCO program. This recognition has influenced the transmission and development of many traditions, especially in China, where competition for recognition between rural communities has resulted in sometimes unexpected outcomes, such as increased commercialization.

Professional Storytelling

Professional storytelling in China dates back to at least the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE), when urban areas in northern and southern China were growing. Huge entertainment areas became normal parts of large cities, especially those such as Hangzhou, Yangzhou, and Suzhou in the Yangzi delta. Over the centuries, a number of forms developed. The most basic form was that of a single storyteller who told lengthy tales of heroes and war. Another popular form was storytelling with musical instruments. In these styles, singing and speaking were alternated in performance and the storytellers accompanied themselves with stringed instruments, drums, or clappers made of wood, bamboo, or metal. In some cases, pairs or trios of storytellers told their tales together. Some stories were short, while some could go on for months, with storytellers performing novel-length stories for an hour or two each day. In some cases, stories were told in marketplaces, or in teahouses, often located in special entertainment zones that might feature other types of performances. These might include juggling acts, martial arts demonstrations or competitions, feats of skill, etc. Rich families sometimes invited storytellers to perform in their homes, providing the women of the household with a chance to enjoy the lively and moving tales.

The most prominent styles of professional storytelling in China today are the pingtan traditions of the Yangzi River delta. Organized into government troupes in Suzhou, Shanghai, Yangzhou, and some smaller cities, several hundred storytellers daily tell tales in dozens of special story houses in the region. Most stories are told two hours a day and require two weeks to complete. One style of storytelling, featuring a single storyteller, is called “straight storytelling” (pinghua). The storyteller uses a small block of wood or jade to slap the table at the start of a performance, letting the audience know the story is about to begin. As the story unfolds, the storyteller uses exciting eye, face, and body movements, along with unusual sounds to mesmerize the audience. The only props are a fan and a handkerchief, which are used to represent objects such as a sword, chopsticks, umbrella, letter, gag, etc. Most of the tales are about ancient Chinese heroes such as the patriotic Song dynasty general Yue Fei, or adventurers and warriors in the classic novels Three Kingdoms and Water Margin.

The other major pingtan storytelling style is “chantefable” (tanci). In this form, one, two, or three storytellers tell love stories, accompanying themselves with stringed instruments. The standard format features a man and a woman who perform together (although duos of women are common today). The lead plucks a three-stringed banjo (or “chordophone”; sanxian), while the assistant plays the pear-shaped lute (pipa). Performances begin with a short ballad, followed by the main story, which is unfolded in a mixture of narration, dialogue of characters in the story, and singing. Often the singing roles are used to reveal the inner thoughts of the characters, a feature that is exciting when used in the telling of love stories between scholars and upper-class beauties, who by convention could speak to each other only in very formal registers. Thus, the audience can often hear what is really going on in the hearts of the characters, which on the surface seem formal and distant. Pingtan storytelling is often heard on regional radio shows and featured on television spots and tourist venues. Click here to watch a tanci ballad performance.

Traditional Performance in Chengdu

Traditional performances of many kinds are a part of the rich history and culture of Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. Some performances are still held in a refurbished opera house located near one of the city’s largest shopping districts. On specific days of the week visitors (many retired) can find various sorts of entertainment to pass the time. Many meet friends for card games and cups of tea. On special days, the house will feature performances of Sichuan-style Chinese opera, in which some characters wear thin masks that can be changed in the flash of an eye to become new characters. Occasionally special variety shows feature a host of performers from various traditions. Collectively those traditions that feature storytelling and music are known as quyi (the “art of melodies”). Styles differ, and part of the interest is seeing so many storytelling variations in one situation. Most performances are moving or exciting extracts or episodes from longer stories. Many different tunes and musical instruments are used. Among the instruments are drums, bamboo, metal, or wooden clappers, stringed instruments, and flutes. Differing styles will use one or more instruments. Performers may be young or old, female or male—all are valued bearers of traditions that are increasingly difficult to view in China due to competition from electronic media. Most of the storytelling styles have or once had similar counterparts in other parts of the country. Click here to view face changing, a traditional Sichuan opera performance.

|

|

Yi Folk Dances

The Yi are an ethnic minority group in southwest China numbering over 10 million. Among the dozens of Yi subgroups are the Lolopo and the Sani. The Lolopo live in an autonomous prefecture in northern Yunnan province.

Each year in Chuxiong, the prefectural capital, large circle dances are held during the Lunar New Year and during the Torch Festival, a special Yi holiday held in early July. During these times, the town square is filled with people of many nationalities who watch all sorts of performances such as lantern opera (huadengxi), local drama troupes, small bands of traditional and western music, and even pop singers. In one corner of the area (right near a huge new performance hall where famous pop stars perform and splendid ethnic fashion shows are held) groups of people form large circles during the evening hours and dance to the music of handmade string instruments called “moon guitars” (yueqin). Most of the dancers are Lolopo, Lipo, or people of other Yi subgroups. However, those of other backgrounds are free to join in. Some circles may have nearly one hundred people, although some may consist of a few lively young people. The dance steps appear simple, but mastering the short kick step, which is repeated in several variations, is not easy to pick up quickly. Such circle dances are held in the rural villages at weddings and other festive events as well in courting activities of the young. Among the best known are the circle dances in the small town of Zhizuo, where women from area villages gather to dance in their highly embroidered clothing and sometimes participate in fashion shows.

The Sani, another Yi people who live in Shilin County (near the famous Stone Forest tourist attraction) also have distinctive styles of folk dances. A common dance form is when lines of men and lines of women dance towards each other, then retreat backwards, all in time with music provided by a flute, and several styles of stringed instruments, including moon guitars. Many of the men play gargantuan three-stringed banjos that wave from their hips as they thrust forward towards the line of women. The dancers will move back and forth for several minutes, until a sort of intensity is reached, then gradually slow the beat until the dancing stops for several minutes. The over-heated dancers rest and chat with friends for a while, until the musicians begin strumming on their instruments and dancers gradually rejoin to repeat the process, sometimes with a few new dancers who join from the crowd. Such dances take place at village festivals, courting sites near villages, and in town squares after the evening rush hour. Choreographed versions of such folk dances are now a central part of the elaborate tourist shows presented nightly at the Stone Forest and are an important part of the local economy. Click here to watch a Sani folk dance performance.

Nuoxi and Dixi Masked Opera

While painted-face opera is the most common in China, in recent years scholars have “discovered” the existence (well known to local people!) of a widespread tradition of masked opera in southern China. This style of opera is found among Han, Miao, Tujia, Dong, Zhuang, Yi, and some other groups. Among the best-known instances are found in Guizhou province. In the city of Tongren, located in the east of the province, there is a masked opera museum dedicated to the preservation of the style known as “Nuo” or Nuotang” opera. Besides the museum, there are several masked opera groups in the area. Traditionally, all the members are male. Some play musical instruments in the troupe band; others are actors. A few actors who play women’s roles grow waist-length hair. Nuo opera performances are associated with complex rituals and the wooden masks are gathered and displayed in rituals held for the spirits they represent before each performance. Performances are often held around the Lunar New Year and are hosted and sponsored by local homes. Hundreds of gods are invited to attend, as well as humans. Among the stories enacted is the tale of Kaishan (the mountain clearing god) who loses his axe in the bottom of the sea and must battle the Dragon King to have it returned. Click here to watch a Nuoxi masked opera performance.

Another style of masked dance, called Dixi (pronounced like “dee-shee”; literally, “earth opera”) is associated with the city of Anshun, located in southwestern Guizhou province. Although Nuo masks are often in natural wood color, the Dixi masks are usually intricately painted in a variety of colors depending on the gods or characters portrayed. Legend has it that this tradition evolved out of entertainment shows held for Han troops sent to the Guizhou frontier in the Ming dynasty. Thus, the plays have martial themes. They are performed in colorful costumes, with those of the generals similar to those worn by corresponding military figures in Beijing opera. In these various mask-making traditions, apprentice mask makers must undergo several years of training and many taboos surround the making and care of the masks.

Shadow Puppet Opera

Shadow puppets have been used for hundreds of years on the Chinese mainland and in Taiwan (where cloth hand puppets are also popular). The northern city of Tangshan, in Hebei province, is famous for its delicate shadow puppets made from mule skin. The puppet makers use special knives to carefully cut out the puppets following ancient patterns sketched on the rawhide. Details on the cutouts are made with black and red ink, and the whole thing is covered with a protective varnish. Each puppet represents a certain role type in traditional Chinese opera. These roles include: young scholar, young high-class woman, old scholar, older high-class woman, and various roles for lower-class characters and clowns. The stage consists of a wooden frame and a translucent cloth screen. Behind the screen the hidden puppeteers raise the puppets up to the stage. Their movements are similar to those by actual live performers, leading some researchers to speculate that the movements of live performers may be related to traditions of puppet theater. The puppeteers speak and sing in high-pitched voices, similar to those in Chinese opera. A small band of percussion and string instruments accompanies each performance, though in recent years some tape recordings are sometimes used. Puppet shows were traditionally held in markets and temple fairs. Today, they are still held in some entertainment districts and featured on local television. The handmade puppets are presently a popular tourist item in some antique and souvenir markets.

In Taiwan, cloth bag (or glove) puppet shows (budaixi) are still popular. They are similar to the shadow puppet shows, but the audiences can see the puppets directly. Cloth bag puppet shows sometimes feature laser light effects and dry ice to increase the effect of performances. Some stories have been adapted into wildly creative television versions.

Kunqu Opera and Beijing Opera

Beijing or “Peking” opera is one of the most recognizable of the Chinese performance traditions. Although it originated in the city of Beijing, there are Beijing opera troupes and fans in many other cities, making it the closet thing the Chinese have to a “national” performance tradition—even though some audiences need subtitles to understand the language. On the other hand, in many areas, local opera traditions are equally rich and enjoy a greater local following.

Beijing opera, however, is a rather recent development, growing out of earlier southern and northern forms of opera and coming into its own only in the early 19th century. Before that time, a southern form known as Kunqu was the most nationally popular form. Kunqu originated in the 16th century in a small city known as Kunshan, close to present-day Shanghai. Noted for its soft music, refined speech, and the overall “delicate” feeling of its performances, Kunqu is a marked contrast with the loud, colorful, and boisterous Beijing opera. However, the operas share certain basic conventions. Typical stories in Chinese theater deal with romances between star-crossed lovers and events in Chinese history, usually of a military nature, often adapted from works of Chinese vernacular fiction.

Both Kunqu and Beijing opera share similar role types, though with some differences. Role types are stock character roles that appear in nearly all traditional Chinese opera (including puppet opera). The common Kunqu role type are young male elite (sheng); older male elite (lao sheng); young, unmarried elite woman (huadan); older elite woman (laodan); lower characters (longtao), and the comic characters (chou). In Beijing opera, the terms are somewhat different: young, unmarried elite woman (qingyi); spirited young woman (huadan; often a maidservant); and the great figures or “painted faces” (jing). Martial women are known as wudan. Each role has its specific costumes, gestures, walking styles, speaking, and singing styles, and make-up or face patterns. The elaborate face paintings of the jing (great figures like generals, heroes, or wise men) number in the hundreds and are one of the most exciting elements of Chinese theater.

Click here to view some examples of Kunqu opera.

|

|

Although audiences for local opera have declined in recent years, new venues in the tourist trade have opened and several international events involving other operatic traditions have brought new attention to the arts. Performers, however, require years of grueling training, and troupes are expensive to support. For the time being, however, the Chinese government is still investing in local troupes and opera training and research institutes.

Epics in China

Epics are very long poems that relate the activities of “exemplary characters” and often play into the self-image and projected identities of ethnic groups or nations. Although some Western scholars once claimed that China had no epic tradition (at least in comparison to the Greek Iliad and Odyssey), in recent decades scholars worldwide have come to realize that some of the world’s longest and richest epic poems are found within China’s borders. Of these, two basic groupings exist, one in north China and the other in the south.

The northern epics tend to be about heroes and warfare. The best examples come from several ethnic minority groups that range from Tibet, across Inner Mongolia (and Mongolia), to northeast China. Among these epics is the tale of King Gesar. The story of Gesar, a mythical Tibetan hero, seems to have arisen in Tibet by about the 14th century and was later adapted by the Mongols and several other groups on the northern grasslands. The story tells of Gesar’s supernatural origins, his coming of age in a great horse race, and his defeats of numerous foreign kings. In Mongol versions, Gesar (or “Gesser Khan” in Mongolian) journeys across deserts and wastelands to the land of the evil Manggus King who has lured one of Gesar’s wives into his lair. Gesar kills the evil manggus and cuts off the giant, human-like creature’s 12 horrible heads. In the epic of Janggar, the story of a mythical Mongol leader, multi-headed manggus often invade the land, usually disrupting lively banquets. Janggar and his men leave their feasting to pursue and destroy the evil creatures which often enslave and eat humans. The Daur people in Heilongjiang province and eastern Inner Mongolia tell similar stories of brave hunters (mergen) who face difficulties in the pursuit of multi-headed monsters that have captured women or relatives.

In southwest China, many of the long narrative poems deal with the creation of the earth and the living beings that inhabit it. Such creation epics are part of the oral lore of the Miao (Hmong), Zhuang, Dong (Gaem), Yao, Yi, Wa, Hani, Naxi, and many other peoples. In some cases, epic performances are given by a series of singers, who take turns in the telling. In some instances, the stories are told in antiphonal style—a sort of “song talk” in which passages are alternated between singers who test the knowledge of their opponents by posing a question at the end of each passage. When one side replies, they then ask a question of what happened next—to which their opponents must reply. And so the story proceeds, sometimes for the several days and nights, with few breaks. Themes in these epics include the creation of the earth, sometimes from the disassembled body a great god or even a tiger; the creation of the suns and moons by early generations of proto-humans; the shooting down of the excess suns (an early attempt to stop global warming!); a great flood that destroys all of the early humans except a brother and sister who survive in a floating calabash (gourd); the creation of contemporary humans as the result of the unnatural marriage between brother and sister; and the story of how humans learned to speak, and then disperse to populate the surrounding areas and become the local ethnic groups. In some cases, epics on heroic themes also exist, as in the Yi story of Zhyge Alu, whose mother was impregnated by blood falling from dragon-eagles circling in the sky above while she was weaving. The unusual child refused to nurse his mother or wear human clothes. A ritualist advised the child to be sent to the wilds, where it was raised by dragons, but later became a great hero. In these lines about Zhyge Alu shooting down the extra suns and moons, notice how the supernatural world of myth converges with the natural world and the realm of humans:

Arriving at the top of Turlur Mountain,

He stood atop a fir tree to shoot,

And he hit the suns with his arrows,

And he hit the moons with his arrows.

From then on, fir trees grew very straight and beautiful.

The fir trees on the mountaintop,

In the third month of autumn,

Are split into shingles to cover log houses,

Allowing humans to establish homes…

(translated by Mark Bender and Aku Wuwu from a traditional ritual text copied by Jjivot Zopqu)

Among the Miao (Hmong) people of Taijiang county in southeast Guizhou province, there is an antiphonal epic tradition featuring a female creator known as Butterfly Mother. As explained in Module 3, Butterfly Mother emerged from a Sweetgum tree and when flying down a river was impregnated by Wave Foam. Thereafter she retreated to a mountain nest where she laid 12 eggs that contained creatures such as dragons, elephants, the Thunder God, and Jang Vang and his sister, ancestor of humans who survived a great flood.

JAPANESE PERFORMANCE TRADITIONS

Introduction

Japan has a very rich history of performing arts, with ancient influences from China, Korea, Central Asia, India, and more recent influences from many other parts of the globe. The origins of Japanese performance traditions can be traced back to the animistic and shamanistic rituals used in local belief systems. Performance traditions known as Kagura and Gigaku were first performed at local shines. Bugaku and Gagaku are important performance traditions long associated with the Imperial Court of Japan. These are also highly ritualistic in nature. Bugaku and Gagaku reached their highest level during the Heian era under the patronage of the Emperor.

During the medieval era of Japanese history Noh drama became an extremely important performance tradition. A form of masked drama utilizing dance and chant as its main elements, Noh remains an austere and moving performance tradition that is practiced to this day. Two distinct forms of drama that came to the fore during the Edo period are Kabuki and Bunraku. Kabuki is a highly energetic and lively blend of music and dance that was popular among the growing urban population. Bunraku is the most advanced form of puppet-theater in the world. It can take up to three people to manipulate one of the large puppets used in Bunraku. While both traditions were at one time widespread, Kabuki theaters are now found mostly in the modern capital of Tokyo while the surviving Bunraku theater is in the city of Osaka. Sharing some features with professional storytelling like Yangzhou pinghua in China, Rakugo is an entertaining style of narrative performance still enjoyed in some urban areas today.

During the modern era Western drama and stage reviews featuring dance routines became increasingly popular and widespread in Japan. Today performance traditions old and new are found throughout Japan.

Tono Storytelling

The small city of Tono is famous for its tradition of local folk stories and legends, which include tales of kami spirits, yokai creatures (see Module 9), strange occurrences, and sightings of kappa—the mischievous strange half frog, half turtle creatures that are the Japanese version of the Loch Ness monster.

Located in Aomori Prefecture, near the northern end of the island of Honshu, the Tono valley is an agricultural region of forested hills, shallow rivers, and brilliantly green and yellow rice fields. The area was once known as a center for horse breeding and locals also produced silk to supplement farm revenues.

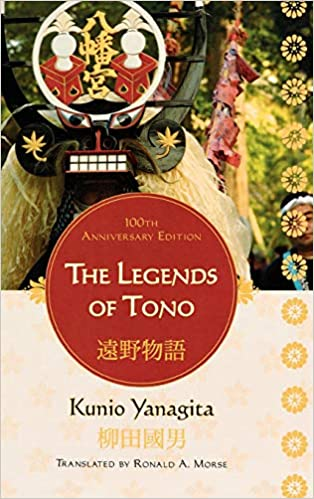

The stories from Tono were brought to national and international attention in 1910 with the publication of The Legends of Tono (Tono monagatari) by the most famous of Japanese folklorists, Yanagita Kunio (1875-1962). Under his efforts, the Tono stories became the best-documented living folk stories in Japan and gave rise to a large body of research on Tono oral traditions. By the mid-20th century, however, it became clear that oral traditions in Japan, like other aspects of traditional culture were in danger of being lost to the overpowering forces of modernization. In response, efforts were made to save the traditions of the Tono area, and especially the famous tradition of folk stories. A local museum was built, historical villages featuring actual and reconstructed buildings were created, and a group of older women (known affectionately as obasan or “grannies”) were recruited to tell folk stories to interested visitors. The cultural preservation efforts also included a museum in the traditional-styled inn (ryokan) where Yanagita sat with local storytellers to record their performances, as well as the Yanagita Kunio Research Center, and several local venues where folk stories are told each day. Click here to watch a Tono storytelling performance.

These venues include a story house located above a tourist shop near the research center with a room featuring a raised storytelling platform and seats for the audience. There is a small traditional fireplace in the floor in front of the platform (to simulate the traditional storytelling situation in a farmhouse). A small story house that is free to the public is in the Tono train station. It is a small room with a table where the storyteller sits, chairs for the audience, and posters depicting the themes of well-known stories. Presently, about 17 obasan, aged 70 to 84, recite stories for tourists in Tono. Each storyteller has a slightly different style but all of them draw on a range of gestures and vocalic expressions to enhance their performances. The storytelling style of today is somewhat like that of the urban-based Rakugo professional storytelling (which has undoubtedly influenced the traditional style in Tono), though the gestures and verbal aspects are less formalized.

One of the most celebrated legends from Tono is that of a teenaged girl named Oshira-sama, which is likely based on an ancient Chinese account of the origin of silk. As the story is still told by the obasan today, long ago there was a poor family who had a teenaged daughter named Oshira-sama and a horse. Eventually the daughter and horse fell passionately in love. One day her father discovered their relationship and killed the horse, hanging it from a mulberry tree. While he was skinning it, the distraught daughter wandered nearby and was suddenly wrapped up in the skin and whisked off to the sky. Later, she appeared in a dream as a horse-headed silkworm and gave the secrets of silk cultivation to her poor family. This tale, in turn was a way in which local people explained the tradition of farm women producing raw silk as a cash crop. In the historical village known as Densho-en, there is a shrine to Oshira-sama which contains thousands of cloth dolls left as offerings to her spirit. The dolls come in pairs—one with a horse head and another with a human head, both carved in mulberry wood. (Silkworms feed on the leaves of mulberry trees and ancient Chinese legends suggest that a silkworm’s body is similar to that of a woman; while the head is likened to that of a horse.) Oshira-sama’s story is popular among Tono storytellers today.

There are many theories about the origin of kappa tales and descriptions and names of the creatures vary throughout Japan. Most accounts describe kappa as being the size of a young child and having green or bluish skin. Their hands and feet are webbed, and their bodies have the appearance of a frog, with a turtle shell on its back. A kappa’s head is often described as being monkey-like, though often with a beak. The top of the head is circled with hair around a flat depression that must be kept filled with water for the kappa to maintain its strength. (Thus, if a kappa is encountered, a strategy for depriving it of its powers is to force it to return a bow.) Kappa are regarded as rather nasty creatures who like to steal cattle, horses (and sometimes even small children), dragging them into rivers to suck out their insides. One story tells of a kappa caught in a barn trying to steal livestock. The angry farmers force it to plead for its life and to promise to never steal from them again. In another tale, a kappa is frightened by a fisherman sharpening a sickle by the river and makes a deal to bring him four fish each day if he stops the sharpening. In many locales there are “kappa pools” (kappa-buchi) where kappa are known to reside. In Tono, one is in a small stream near the Jokenji Temple. A kappa festival is held each year at the Jokanzei Hot Springs near Sapporo on Hokkaido island. This is close to a famous kappa pool where a young man is said to have drowned and later married a kappa and raised children with her. Many images of kappa or similar yokai creatures appear in anime films and cartoons in Japanese popular media today. In Tono, they are included in multi-media museum exhibits and local marketing campaigns.

Sources:

Yanagita, Kunio (1975). The Legends of Tono. Translated by Ronald A. Morse. Tokyo: The Japan Foundation.

Information from Tono Tourist Bureau and the Yanagita Kunio Research Center.

Bunraku Puppet Theatre

Puppets appeared in Japan by the 8th century, sometimes in conjunction with Shinto rituals. A very developed puppet theater dates to the late 16th century, when the arts of puppetry, storytelling, and the music of the three-stringed banjo (shaminsen), combined in a form called Joruri. Well-known Kabuki playwrights, such as the prolific Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724), created scripts for the puppet theater that equaled those for other types of drama in sophistication and popularity. Among his works was the sensational “The Love Suicides at Sonezaki” (Sonezaki shinju), based on the real-life suicides of young lovers. The most famous puppet theater play, “The Forty-Seven Ronin” (Kanadehon chushinguru) is about the mass suicide of 47 samurai who were convicted in a revenge killing they executed out of loyalty to their feudal lord. Such puppet plays were performed for popular audiences in the pleasure districts of Osaka, Edo (Tokyo), and other cities. By the late 18th century, the term “Bunraku” became common in referring to certain types of puppet theater that were developed by an innovative puppeteer named Uemura Bunraku-ken (1737-1810) from the island of Awaji. After a period of decline in the 20th century, Bunraku has received a degree of government protection in Japan. Due to the decades of strict training required to become a master puppeteer, however, it is becoming increasingly difficult to find devoted young people willing to train as puppeteers for Bunraku.

Besides stories, the conventional elements of Bunraku include the puppets, stages, puppeteers, musicians, and the so-called “chanters.” Bunraku puppets themselves are about two-thirds the size of a human adult and the larger ones (main characters) require three people to manipulate them. Intricately assembled of wood, bamboo, paper, metal, and cloth, these puppets consist of a light frame covered by a costume. Heads have many moving parts and can create a variety of expressions and sometimes surprising movements. Most female puppets lack legs or feet; it is the feet and arms of the male characters that take years to learn to manipulate properly. It is said that trainees must study the movements of the feet for ten years, the left arm for ten and finally ten for the head and right arm until becoming a fully qualified puppeteer. The two puppeteers who control the feet and left arm wear black costumes with hoods, while the master puppeteer who controls the head and right arm is bare-headed and can be seen by the audience throughout the whole performance. To watch an example of Bunraku puppet theatre, click here.

Although highly skilled, in feudal times the puppeteers were considered lower class entertainers. However, the chanters, one of whom sits to one side and narrates the story as the action proceeds, were once honored with a rank equal to that of samurai. The chanter’s art arose in the 7th century when blind monks recited prosimetric tales from the Buddhist scriptures, and later tales of warfare like the Tale of Heike. Centuries ago, chanters accompanied themselves on biwa lutes (similar to the Chinese pipa), though by the 16th century the three-stringed shamisen banjo (chordophone) came in vogue. Chanting takes years to master and the standards of voice control are extremely strict. The major Bunraku theaters in Tokyo and Osaka are elaborate venues similar in many ways to Kabuki theaters, though modified to the needs of the puppeteers who must constantly move back and forth behind the stage.

Noh Theater

Though of humble origins, Noh (No) theater is today the most refined of Japan’s many theatrical traditions. Rooted in theatrical traditions that appeared in Japan from the Asian mainland (possibly India) by the 7th century and developed through the 14th century, Noh grew directly from several related forms, including Saragaku (“monkey music”) and Dengaku (“rice-field entertainment”). In some ways similar to the masked dramas of Korea and China, Noh took masked drama to its greatest heights during the lives of its two great innovators, Kan’ami Kiyo’tsugu (1333-1384) and his brilliant son, Zeami Motokiyo (c.1363-1443). Zeami was a consummate actor, playwright, editor, literary theoretician, and director who left a mark on Japanese theater as profound as that of Shakespeare on English drama.

The training of Noh performers demands discipline and adherence to convention. On the other hand, the aesthetics of Noh stress that both performer and audience share in the creation of extremely sensitive feelings and difficult-to-describe psychological states similar to those achieved in Zen Buddhism. Extensive training is required to master the voice roles and the “slow motion” dance steps—which to the untrained eye often seem simple to execute. Actors must learn to meld their roles in accordance to the sounds produced by the Noh musicians, who play drums and flutes to one side of the stage. To achieve the ultimate effect, performers must be completely in touch with what its theoreticians have called “the Absolute” in both mind and body, learning to chant and move in accord with what Zeami called “the invisible heart.”

Although thousands of Noh plays have been written or performed, about 240 plays are commonly staged today. The classical texts on Noh divide the plays into five main categories: plays about gods, warrior plays, woman plays, plays about madness and ghosts; as well as demon plays featuring various supernatural beings. These plays involve certain stock roles and take place on a special wooden stage, which includes a long walkway from offstage and a backdrop with a painted pine tree. The main actor is known as a shite, while the supporting role is called a waki. In some plays a fool and a few other subordinate characters may appear. A chorus, which sits to one side, chants out the thoughts of the main characters and comments on the action, adding an intriguing dramatic dimension to performances.

The plots of Noh plays tend to be minimal, and often involve a wandering person, often a monk, who happens to appear in a far-flung place in the mountains or by the sea, and encounters a ghost or other supernatural being. The occasion is often marked by the supernatural being pouring out its grief over some unrequited incident in its former life, as in the woman play, Pining Winds (Matsukaze). Other famous plays include The Feathered Mantle (Hagaromo) about a deity in a feather cloak who descends to earth to bathe but is spied by a mortal, and Granny Mountains (Yamamba), a demon play about a mountain crone and her “counterfeit” double. Plays are usually divided into two major parts interspersed with a number of smaller scenes. Short comic plays called Kyogen are performed between plays when a series of plays are presented.

Ohio native, President Ulysses S. Grant visited Japan in 1879 and was treated to a Noh performance by the new Meiji rulers. His praise of the event helped Noh gain a foothold in the modernizing Japanese society of the times. To watch a Noh performance, click here.

Sources for Japanese drama:

Ortolani, Benito. (1990). The Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Quinn, Shelley (2005). Developing Zeami. Manoa: University of Hawaii Press.

Tyler, Royall, trans. (c. 1978). Pining Wind, A Cycle of No Plays. East Asia Papers No. 17. Ithaca: Cornell University.

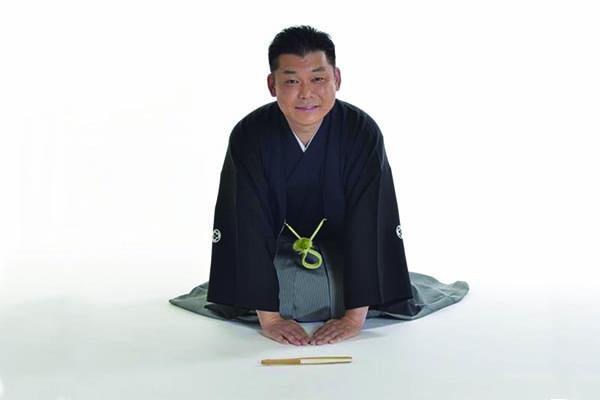

Rakugo Comic Storytelling

Rakugo is a form of professional storytelling that has its roots in Buddhist storytelling of the 9th century and developing into its present form in the Edo period. After World War II it enjoyed a revival in the 1960s, when other traditional arts were being reassessed and appreciated in the wake of the intense modernization of Japan since the Meiji Period in the late 19th century. Similar in some ways to Chinese professional storytelling, the Rakugo repertoire is mainly short comic stories told by one performer (called hanashika) seated on a mat on a raised platform who employs stylized facial expressions, hand and body movements, and a dazzling array of voice registers to enthrall and entertain the audiences with traditional stories. A few storytelling houses (yose) are still active in Tokyo and Osaka which attract diverse audiences, though the traditional audience was older males. Storytelling audiences today extend to audiences on television and social media. The props used in storytelling are a folding fan and a handkerchief.

Traditionally there have been two main story types, the ninjo banashi, or longer story form, and the shorter ochi-gyagu type. The ninjo banashi requires great physical stamina to create the sentimental “human feelings” (ninjo) that enliven the depicted characters and touch the hearts of the audience members. These emotions often come in conflict with the sense of obligation (giri) that people experience in their lives. The storyteller utilizes humor and irony to create a sympathetic character who faces all manner of obstacles, such as a those in a stock traditional plot involving a young heir who wishes to wed a women his family opposes. So much energy is required for this dramatic type of telling that older performers tend to prefer the shorter style. The shorter ochi-gaygu type is easier to adapt to contemporary themes and easier to learn. Both styles indulge in a sort of suspension of belief in a surreal state called kyo in which the bounds between “reality” and “un-reality” are crossed. The various unreal worlds into which the storyteller lures his audience include that of the con man, the eccentric, the spectral world, and the world of “bizarre fluctuation” in which “all logic and common sense are thrust aside” (Morioka and Sasaki 1990:109).

The storytelling language is filled with various plays on words and types of speaking associated with the social roles of characters that draw on the rich traditions of Japanese language and culture. Two common ways of speaking are the sharp words of fighting called tanka (which include many offensive terms such as “stingy creep” and skillful retorts; and passages of koto, or stereotyped speech that display “bogus knowledge or assumed superiority” when characters interact—adding to the interest of the story. Much more could be said about the many sophisticated verbal techniques used in Rakugo storytelling.

A younger storyteller who wishes to popularize Rakugo outside Japan is Mr. Yanagiya Tozaburo. Mr. Tozaburo has given several performances and workshops at The Ohio State University and encourages students of any background to learn the art. Click here to watch Mr. Tozaburo’s performance of “The Zoo.“

Sources:

Morioka, Heinz and Muyoku Sasaki (1990). Rakugo: The Popular Narrative Art of Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Pre

Ainu Dance

As discussed in Modules 1 and 3, the Ainu, the original people of the northernmost island of Japan, Hokkaido, and neighboring Sakhalin Island in Russia, were traditionally a hunting and gathering people and followed that lifestyle into the early 20th century. Ainu culture has been under pressure from the Japanese since the 17th century, when war, epidemics, and immigration from other islands of Japan began to have severe impact. By the early 19th century, the Ainu population diminished from about 24,000 to about 16,000. Today the population is estimated to be between 20,000-100,000, including some who have partial Japanese (majority) ancestry. Since the late 19th century, many of the old ways of the Ainu have been lost, and the forces of acculturation are strong today, despite concerted cultural revival movements led by Ainu political activists in recent decades.

Traditional Ainu villages were small settlements near water and forests. Houses were made of wood, each one having a large fire pit in the center room in which food was cooked and around which families gathered to eat and socialize. Many wild plant foods and protein from salmon, deer, and bear were available from the land and waterways. Customs and food gathering strategies followed the four seasons of the year. Trees were a valuable resource for building houses, dugout boats, eating utensils, storage containers, hunting and fishing tools, ritual objects, and even clothing—the inner bark of certain trees was woven into sturdy cloth.

As discussed in Module 3, the Ainu hold many beliefs surrounding the relation between humans and the gods of nature. One belief is that gods visit the human world disguised as animals (especially bears) and present themselves to worthy hunters. Such a disguise is called a hayokpe. When such an animal was killed during an Ainu hunt, it was believed that the spirit of the god was released. As it was believed that the god had brought the hide and meat of their covering as a gift to the people, great ritual attention was given the visitor. To thank and honor the god, the people gave large parties that included singing, dancing, and the offering of wine and shaved pieces of willow called inau. Another activity at such parties was the singing of ancient epics concerning the activities of the gods. Once the welcoming ceremonies and feasting activities were over, the god would be ritually sent back to the world of the gods in a ceremony called iyomante (“sending-off’), where it was hoped he or she would encourage other gods to visit the human world. (In 1984, the dance iyomante rinse was designated an “important cultural property” by the Japanese Ministry of Education.)

Epics (yukar) were also performed around the fire pit on long winter nights. The singers would recite passages of the tale, beating time with a short wooden stick on the wooden sides of the fire pit. Audience members, who also beat time with their sticks, occasionally chimed in with the sounds “het! het!” to encourage the singer. It was not unusual for such singing and ritual sessions to last all night long. Other performance styles included choral folksongs and the playing of a wooden mouth harp called a mukkur. This mouth harp is made of a thin sheet of bamboo into which is cut a thin flap (ventil) that vibrates when the player blows on it. The flap is fixed with a string that is pulled to modulate the sound. The harp is in some ways similar to those used in Siberia and southwest China. To view Ainu dance and musical tradition, click here.

Sources:

Philippi, Donald L. (1982). Songs of Gods, Songs of Humans. San Francisco: North Point Press.

Materials from The Ainu Musuem in Poroto Kotan, Japan.

Kabuki Theater

During the Tokugawa (1603-1868) there was an explosion of popular culture in the large urban centers of Edo (Tokyo) and Osaka. This was facilitated by the newfound peace brought about by the Tokugawa government. Kabuki, a visually stunning form of drama based around music and dance, became a symbol of this era.

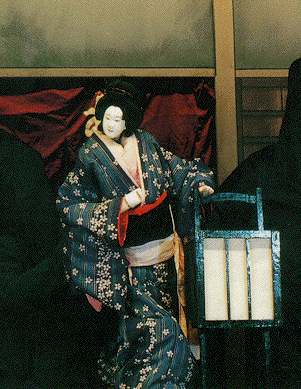

The origins of Kabuki are traced to a female performer named Okuni. While the exact details of her life are largely unknown, she is credited with starting the performance tradition that would later become what is now known as Kabuki. She was the leader of a troop of female performers in the early 17th century who traveled throughout the countryside. Drawing upon folk tales and other popular forms for influence, Okuni’s theater became extremely popular. However all-women Kabuki was seen as too risqué by the Tokugawa government and was banned. Later Kabuki was performed by all men troops, giving rise to the onnagata, or female impersonator. An idealized vision of feminine grace and spirit, the onnagata became the symbol of the Kabuki theater.

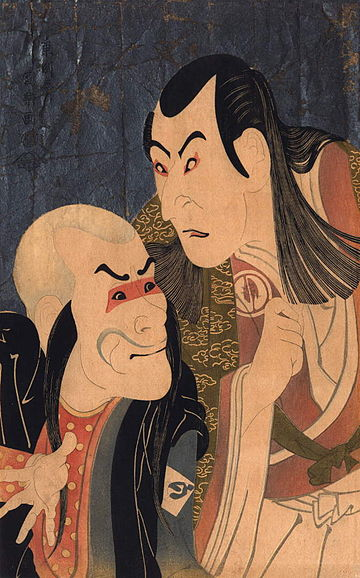

By the mid-Edo period, Kabuki became big business in the entertainment districts of the cities. Edo was the home of some of the biggest Kabuki theaters. At this time many famous playwrights such as Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724), Takeda Izumo (1691-1759), and Namiki Sosuke (1695-1751) wrote many of the most famous plays in the tradition. Brilliant actors populated the stages of Edo: Ichikawa Danjuro II (1689-1758), Danjuro IV (1712-1778), Nakamura Nakazo I (1736-1790), and Matsumoto Koshiro IV (1737-1802) were the rock stars of their day, pulling in huge crowds.

Unlike Noh, which strives for austere beauty, Kabuki is a large scale, stylish affair. Large orchestras of chanters, drummers, and shamisen (a type of three stringed chordophone originally found in Okinawa that became popular at this time) provided the music for the onstage drama. Actors wore vibrant, bright costumes and often underwent several costume changes in a play. Dance, especially in the onnagata roles, was extremely important and often the highlight of a performance.

Kabuki plays were populated by bold samurai, frightening ghosts, beautiful women, and desperate lovers. These themes appealed to the rising urban middle class, the main demographic for Kabuki during this period. While Kabuki no longer enjoys the popularity that it once did it still remains one of the most distinctive forms of theater in Japan today. Click here to watch a Kabuki theatre performance.

KOREAN PERFORMANCE TRADITIONS

Introduction

Korea has an array of performance traditions that include farmer’s music (nongak) and folk dances, drama (talchum), acrobatics, and storytelling pansori). All these forms have been strongly influenced by native shaman ritual, popular Buddhism, or sometimes both. There are also more elite traditions of music, poetry, and ritual that derived from contact with Chinese imperial culture and survive in traditional music institutes and ceremonies held regularly at Confucian temples.

Traditionally, professional performers were ranked among the very lowest of classes socially and in many cases performers came from families of performers. Some of these performers seem to have descended from upper-class youths trained in music, dance, literature, and military skills in the “Flower Youth Corps” (hwarangdo) of the Silla period, whose descendants fell out of favor at the decline of that era and supported themselves by a variety of rituals and popular entertainments.

Over the centuries professional performers were identified by a variety of names, including the term kwangdae, often applied to professional storytellers. The main audience for such performers was the royal court and local government officials. Three major gatherings of entertainers were held at the king’s court each year as a part of rituals designed to invoke blessings from the supernatural powers of the universe and to avoid bad luck for the realm. Over time, certain performances were influenced by contact with literary men, leading to the development of oral genres which often included content found in written literature, such as in the pansori storytelling described below.

Many of the traditional performance styles described in this section were developed during the Joseon (Yi) dynasty. By the early 20th century, many styles of performance were in crisis, under pressures from colonization, industrialization, urbanization, and war. Various private and government attempts have been made to revitalize several of these traditional forms in the last few decades. Moreover, the social position of traditional performers has risen and some of the best have been honored as “national treasures.” Samulnori, a group of modern percussionists have revitalized Korean farmer’s music into an exciting new performance tradition that has wide appeals.

In this section, we will focus on several of the outstanding traditions practiced in South Korea, all of which have enjoyed some degree of government sponsorship since the late 1960s. Where applicable, information on performance in North Korea (much of which is politically related) will also be examined.

Sources:

Park, Chan (2003). Voices from the Straw Mat: Toward an Ethnography of Korean Story Singing. Manoa: University of Hawaii Press.

Pihl, Marshall R. (1994). The Korean Singer of Tales. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hogarth, Hyun-key (1997). The Hahoe Mask Dance. Information Materials [Korea University and the Korea Foundation]. Seoul: Korea University, pp. 33-41.

Salpuri Dance

Salpuri, which literally means “spirit-cleansing” dance, is a dance form derived from the music and movement of Korean shamanism. The dances were once part of rituals designed to bring good luck to and drive negative forces from the home or king’s court. Although largely detached from shaman rituals today, salpuri has become a sort of classical dance imbued with many meanings related to the Korean historical experience, the identity of the Korean people, and even patriotism. The emotions expressed are those of sadness and anxiety, reflecting in part the Korean aesthetic of han, or grief over loss. The high degree of control over posture and limbs also suggests the Neo-Confucian stress on proper movement, an embodiment of the virtues of propriety. The dance is often performed in the finest performance venues in Seoul and other large cities throughout Korea. During the Democratic Movement in the late 1980s, salpuri was sometimes performed during protest marches. Although there are several regional styles of salpuri dance, the most influential form developed in the Honam region in the southwest of the peninsula. In a typical salpuri dance, a women dressed in a white dress moves in a controlled, halting manner within the notes supplied by a small orchestra of wind and percussion instruments. The trademark of the Honam style is the long white cloth gracefully manipulated by the dancer, which symbolizes the connection to the spirit world. The dancer moves slowly at first to the rhythmic cycle of music, her energy building as both her movements and the intensity of the music increase until a sort of catharsis is reached by both audience and performer. In reference to its roots in shamanism, the dancer’s movements have been sometimes described as trance-like. Click here to watch a performance of salpuri dance.

Talchum

Masked dance performances are held in many parts of South Korea. Collectively, they are known as “Talchum,” which means “masked drama.” Although styles of masks, singing, and other features of performance vary from community to community, there are many similarities between the local traditions. Masked drama also has a close relationship to Korean shamanism. In some places, masked dramas are still part of the shaman ceremonies known as gut, which, as discussed in Module 3, are sponsored by families or communities to ward off harmful supernatural forces. In some places, once the ritual aspects of the gut have been enacted, the shamans don masks to become actors in the drama, held as entertainment for the helpful gods and ancestors as much for the living audience. In certain communities, plays were customarily performed episode by episode in the front yards of village households. Performances feature dancing, speaking, and singing, all accompanied by the beating of drums, gongs, and other instruments. Traditionally, actors have tended to be male, though in some areas women (often those who are female shamans or shamanka) participate as actresses or in the orchestra.

Strict customs also surround the making, use, and disposal of masks. Depending on the locality, masks are made of papier-mâché, gourds, or wood. The wooden masks made in Hahoe Folk Village in the Andong region are prized by collectors and take great skill to carve. Folklorists in Korea have estimated there are around 450 different human and supernatural characters represented by different masks. Stock characters include the yangban nobleman, scholar, village coquette, blushing bride, withered granny, simpering fool as well as more ominous characters such as the smallpox god. In some communities, the masks were burned after a performance, while in other places, they were kept in a sacred place while not in use.

The themes of many of the dramas satirize the hypocritical or oppressive behavior of traditional upper-class officials and landowners of the yangban class. The content can be somewhat earthy. One play often performed in Hahoe Village concerns two local scholars who fight over the dried genitalia of an ox, which were regarded as helpful to the libidos of middle-aged men. At the high point in the action (stimulated by the appearance of the village coquette), a withered granny scoops up the prize, which the tussling men have dropped in the street. She crows in delight as she points out the foolishness of the “lofty” scholars. This drama is often performed for tourists in Hahoe Village, performances beginning with the actors parading around the performance arena with an actor on their shoulders wearing a bride’s mask representing the local goddess. Click here to watch an informative video on Talchum.

Farmers’ Dances (Nong-ak)

Music has been performed by Korean farmer folk for millennia. Called nongak in Korean, this music was performed for both ritual and entertainment purposes. Small bands often played drums, gongs, and other musical instruments to accompany other farmers during planting and harvesting. Somewhat different styles of dance and music are found on various parts of the peninsula, especially in the differing environs of the coastal and mountain areas. As the tradition dwindles in rural areas, new contexts of performance have grown including at folk museums, in schools, through social clubs, and as organized by cultural troupes. Some groups of performers number in the dozens. Dances and music are often led by a leader with a gong. As time has passed, the dances, music, and costumes have become more refined and consistent with their new settings. For example, amazing displays of energetic folk dance and music were made at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, and more recently at World Cup soccer matches. For more on Nongak, click here to watch an introductory video.

Pansori

The most popular form of professional storytelling in Korea is called pansori sometimes translated as “One Man Opera.” This translation is somewhat inaccurate today, as women storytellers have outnumbered men since the 1920s. Pansori is a Korean version of the widespread prosimetric storytelling—or mixture or speaking and singing—used by monks to spread stories of Buddha that can be traced back to over a thousand years ago throughout East Asia. In Korea, what became known as pansori stories were first told by itinerant performers who often sang and told stories at shaman rituals.

Eventually a distinct style of storytelling developed that was performed in marketplaces, entertainment districts and the homes of wealthy patrons. The trademarks of old time pansori storytellers were a straw mat that, when unrolled, became an instant performance arena. Standing on the mat, the performer would alternate between speaking and singing to tell one of approximately 12 well-known stories. (Today 5 of these stories are still known in their entirety).

The storyteller uses a large folding fan as a prop and begins a performance by dramatically opening it. The storyteller is accompanied by a drummer, who beats out a complex series of rhythms using a wooden drumstick on a double-headed drum. At moving parts in the story, when the storyteller is trying her best to use her voice to move the audience, the drummer and sometimes members of the audience will call out in encouragement. In some instances, a storyteller will perform alone, beating the drum as well as speaking and singing.

Performances can last from half an hour to several hours depending on the situation and story. Storytellers must train their voices for years in order to get used to the long storytelling sessions which employ many voice styles that range from very low to very high pitches. Some performers train by standing amid a roaring waterfall, beating time on a rock with their drum stick as they attempt to sing louder that the rushing water.

The most famous of the pansori stories (which were also available in printed form) are the “Story of Sim Chong” and the “Story of Chunhyang.” Both stories feature young heroines who steadfastly follow Neo-Confucian virtues to aid their parents or protect their dignity in unjust circumstances. Sim Chong allows herself to be sacrificed to the sea god by a group of pirates to restore her blind father’s sight. In reward for her filial piety, in some versions she eventually becomes Empress of China.

The famous Chunhyang story is the Korean equivalent of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet.” The plot concerns a young woman, Chunhyang who holds an ambiguous social position: she is the daughter of a kisaeng (a female entertainer comparable to the Japanese geisha) and a yangban aristocrat. One day a young aristocrat, Yi Mong-ryong sees Chunhyang playing on a swing in her courtyard. The two meet secretly, fall in love, and hold a private marriage ceremony (followed by a risqué wedding night). Soon after, Yi’s family is transferred to the capital and the young couple is separated. After some time, a new magistrate comes to Chunhyang’s city (present-day Namwon) and soon hears of her great beauty. But when she refuses to enter his court as a kisaeng, he imprisons her and forces her to wear a heavy wooden collar. Her husband Yi returns from the capital disguised as a poor aristocrat after passing the civil service examination and pays a furtive nighttime visit to Chunhyang’s mother. He then goes to see Chunhyang in prison. Moved by her loyalty and suffering, he crashes a party in the magistrate’s courtyard the next day and mocks the greedy, rapacious ruler with a sijo poem detailing the corrupt practices of local officials. Once the poem is read, a party of soldiers swarms in and captures the evil magistrate. Yi then reveals that he is the highest-ranking royal inspector. He at once orders Chunhyang brought before him. In front of the assembled crowd, he demands that she become his courtesan. She steadfastly refuses, still not realizing who he is. After everyone clearly sees her filial and chaste nature, Yi goes to her and reveals his true self, bringing her suffering to an end. “The Story of Chunhyang” has been made into several full-length films since 1923, including an award-winning one released in 2000.

Click here to watch pansori training followed by a performance.

Flute

Like other cultures in East Asia, Korea has a strong tradition of flute music. The Korean bamboo flute is known as daegum, and is one of several flute styles. As a form of transverse flute, the daegum has 7 figure holes—but only 6 are actually played (the 7th is called a “ghost hole”). Flutes are made of special yellow bamboo with a thick stem that is harvested in early summer at specific times on the Lunar calendar. Some instruments have been in use for many decades. Records dating to the ancient Silla kingdom mention flutes, and there has always been a close connection between flute music and the sounds of nature. To watch a Korean bamboo flute performance, click here.

Source:

Lee Hyong-kee (1995). Korean Culture: Legacies and Lore. Seoul: The Korea Herald.

Selected Sources:

Bender, Mark (2003). Plum and Bamboo: China’s Suzhou Chantefable Tradition. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Mair, Victor and Mark Bender (2011). The Columbia Anthology of Chinese Folk and Popular Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

Additional Media Playlist

This playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities. Most content appears below in order of appearance within the text.

- Chinese Performance Traditions

- Japanese Performance Traditions

- Korean Performance Traditions

- Tibetan and Mongolian Performance Traditions

- The Epic of King Gesar

- Mongolian epic poetry

- Mongolian Biyelgee dance