5 Module 4: Languages of East Asia

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

Introduction

The languages of East Asia form a complex mosaic. Most languages spoken in the cultural areas of China, Korea, and Japan fall into two large language families that are structurally very different. These two families are the Sino-Tibetan family and the Ural-Altaic family. The Chinese topolects (sometimes called “dialects”) are in the Sino-Tibetan family. Linguists, however, often place Japanese and Korean in the Altaic branch of the Ural-Altaic family of North Asia, the same family as Mongolian.

What complicates the picture is that centuries ago, both Korea and Japan borrowed their early writing systems from China. They later created writing systems inspired by the component parts or general shape of Chinese characters. These systems were syllabaries (something like alphabets), which were able to efficiently represent the sounds of Korean or Japanese. Moreover, over the long course of cultural interactions between the regions, many words have been borrowed back and forth, with many Chinese words absorbed into both Korean and Japanese.

China, as a cultural whole, is very diverse, and this diversity is reflected in the languages spoken there. Aside from the Chinese topolects, many ethnic minority languages are also spoken, most falling within the two major families mentioned above.

The following sections outline some basic facts about the spoken languages of East Asia, including descriptions of each individual language. In the second part, the writing systems are introduced.

The Spoken Languages in East Asia

Chinese Spoken Language

“Chinese” (Zhongguohua) is the name for a group of related topolects (dialects) spoken by the Han ethnic group in the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, and Chinese (Zhonghua minzu) communities in other parts of the world. All the Chinese topolects are in the Sino-Tibetan family, which also includes ethnic minority languages such as Yi and Tibetan. The major topolect regions in China are Mandarin (east, west and southwest versions); Cantonese or Yue (Guangdong and Guangxi areas); Xiang (Hunan area); Wu (lower Yangzi delta), Min (northern and southern styles in Fujian and Taiwan); Gan (Jiangxi); and Hakka or Kejia (most popular in Eastern Guangdong, and regions of Fujian and Jiangxi provinces). Since it is difficult or sometimes impossible for speakers of many of these topolects to understand each other, as early as the Qin dynasty, two thousand years ago, there have been attempts to employ a linguistic medium that could be understood by officials all over China. Under the pressures of building a modern state, Chinese governments in the 20th century decided to adopt a national standard tongue that would be learned by everyone. In the People’s Republic of China this standard was based on the Beijing dialect (topolect), sometimes called Mandarin. On the mainland of China this standard language is called Putonghua, or “Standard Chinese.” In Taiwan, it is called Guoyu or “National Language.” Thus, most people in China speak both their own home language or topolect and Standard Chinese. Most television programs, films, radio, newspapers, textbooks, popular literature, and other media are in Standard Chinese. However, in Hong Kong (where Cantonese is common) and to some extent in Taiwan, some media use local topolects.

In the link in the playlist, you will find examples of pronunciation in several major Chinese topolects (dialects).

Tones

Chinese differs from Japanese and Korean in three important ways. The first is tones. All the Chinese topolects (and languages such as Hmong, Yi, Zhuang, Vietnamese, Thai, Laotian, Cambodian, Burmese, etc.) employ tones to differentiate the meaning of sounds in the language. Since the number of sounds in Chinese is fairly limited, tones are used to differentiate similar sounds. Tones are conventional ways of raising or lowering the pitch of a sound. In Standard Chinese, four tones are used. In some cases, there is no tone on certain words, and that is defined as “neutral tone.” In some topolects (such as Cantonese) as many as seven or even nine tones are used. To the untrained ear, the tones may sound alike or similar, but they represent different words to the trained ear. In a spoken sentence, tones do not sound as strong as when they are articulated individually, due to the influence of the intonation of the sentence as a whole.

Verbals

A second interesting feature of Chinese is the way verbals (that is, units of speech that act like verbs) are handled. While in Japanese or Korean endings are added to verb stems to determine aspect (when something has happened, is happening, or will happen), this is not the case in Chinese. Instead, Chinese relies on the context or situation in which the conversation is taking place as well as marking sounds called “particles” that are placed within or at the end of an utterance to give the listener clues about aspect. One common particle in Chinese is le, which indicates a “change of condition or state” (Ramsey 1987:55). The particle le only represents a change of condition and is independent of the verbal. Also, in Chinese sometimes it is not necessary to explicitly say the pronoun, such as “you” or “I,” because that part of speech is understood by context and therefore does not need to be spoken.

Spoken Question Particles

The particle “ma” is the most common question particle in Standard Chinese, used for yes/no questions. Like Korean and Japanese, Chinese uses verbal (spoken) question marks. That is, questions are marked not by the change in pitch of the last word or word order in an utterance, as in English, but by voicing a question particle. Thus, in the common greeting, “Nĭ hăo ma” (“you good question-particle” or “How are you?”), the “ma” serves as a spoken question mark. Without that “ma” the greeting “Nĭ hăo” becomes “Hello” (literally “you good”). Other topolects have similar features, though not always coming at the end. In the Suzhou topolect, which belongs to the category of Wu topolects, the question particle is “a” and can be placed before the verbal: “Ne a hae” (“you question-particle good” or “How are you?”)

Finally, Chinese differs from Korean and Japanese in sentence order. Chinese sentences tend to be organized in the SVO (subject-verb-object) pattern, like English. Korean and Japanese are SOV languages.

Non-gender specific pronouns

A difference between Chinese and the European languages often studied by English speakers is that there are no gender-specific pronouns. That is, there is no “he” or “she” in spoken Chinese. In Standard Chinese, the pronoun “ta” can mean “he” or “she” or “it,” depending on the situation. In writing, however, the “ta” can be written with a graph representing a male (他) or one representing a female (她) or one representing an animal or a thing (它), though they are still pronounced in exactly the same way. So, in the spoken sentence “Ta chi pingguo” (“s/he/it is eating apples”) only the context of the situation will give you a clue to the gender of “ta.”

Plurals and Classifiers

Instead of adding an “s” to the ends of nominals (noun-like parts of speech), to make a plural (such as “three horses”), Chinese employs classifiers or measure words. Classifiers and measure words are usually functionally interchangeable, but a classifier is a particle without meaning outside its use in counting things, whereas a measure word is a word that denotes a specific measurement, like a “cup” or a “slice.” There are many measure words, all used in conjunction with things that share somewhat similar characteristics. For instance, flat things like paper or photos use the measure word “zhāng,” birds employ “zhī,” books and magazines use “běn,” long and curvy things like fish, snakes, and rivers use “tiáo,” and cars, buses, and bicycles employ “liàng.” Therefore, the Chinese for “one car” is “yí liàng chē” (one measure-word car), and “three books” is “sān běn shū” (three measure-word book). In English, we also use measure words, such as “a loaf of bread,” “a piece of paper,” or “a bottle of cola.” However, while both “I had three bottles of cola” and “I had three colas” are acceptable in English, it has to be “Wŏ hē le sān píng kělè” (“I drank le-particle three bottle-as-measure word cola’) in Chinese, and no equivalent of an “s” is added to the noun to make it plural.

The most common classifier in Mandarin is “ge,” which is used as a specific classifier for people and many other things. “Ge” is also a general classifier, however, which means that it can be and is often used in place of other classifiers and measure words, especially in informal and spoken language. For example, Mandarin speakers would say: “Wǒ chī yī gè píngguǒ” (“I eat one measure-word apple”). In the Wu topolect, however, “zhi” is the most common measure word. So, in the “eating an apple” example, people in the Shanghai and Suzhou area will say “yi zhi pingguo” instead of “yī gè píngguǒ.”

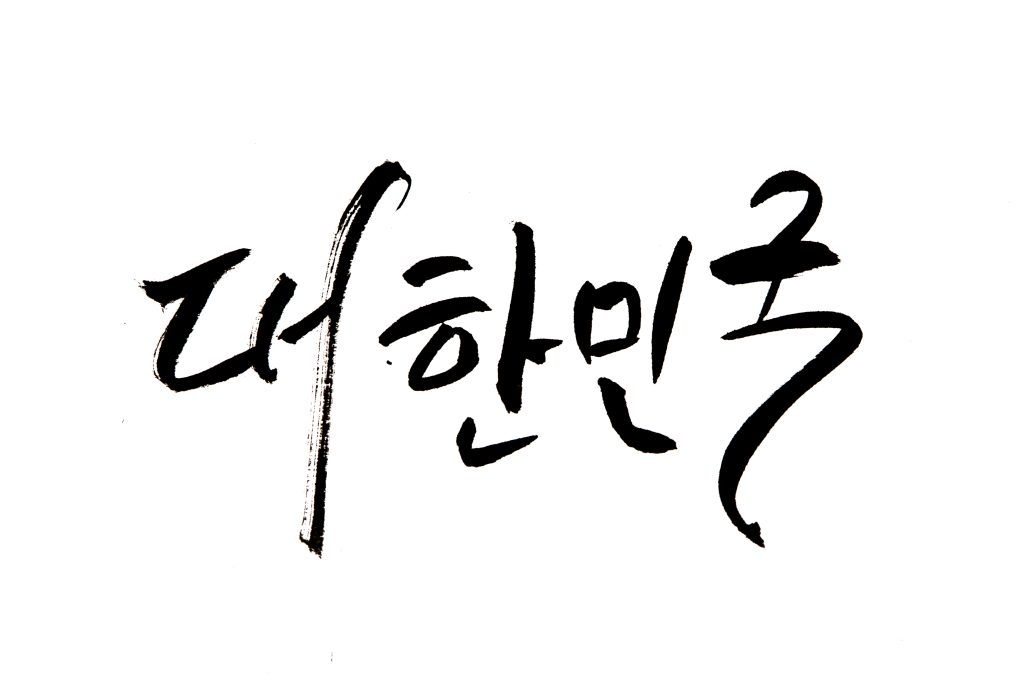

Korean Spoken Language

Korean (한국어, Hangugeo) is spoken in both North and South Korea and in Korean communities in the United States and other parts of the world. Although there are regional dialects (variations) of Korean, they are all more or less mutually intelligible and present a much less complicated picture than the Chinese topolects. The main dialect areas (which correspond to the old Three Kingdoms) are the north, southeast, and southwest. The Seoul dialect is the basis of standard pronunciation in South Korea. In North Korea, accent, vocabulary, and idiomatic expressions sometimes differ from those in the South. Korean is often placed in the Altaic language family (along with Mongolian), though its exact placement is still subject to debate. Unlike Chinese, Korean is not a tonal language.

The sentence structure of Korean is similar to that of Japanese: subject-object-verb, or SOV. Verbs are not conjugated (sentence particles are used to determine tense), but endings are added to verbs in order to reflect the status of the speakers and listeners. Thus, as Korean children grow up, they must learn to use the right verb endings so that they confer proper respect to those whom they are addressing. If a person uses the wrong verb ending when addressing someone higher or lower than they are on the social scale, it is considered a social blunder. Generally, the higher a person’s status (in relation to the speaker), the longer the verb ending.

The video in the playlist below will teach you how to formally and informally introduce yourself. It will also talk about some gestures that go with the greetings.

One of the interesting things about Korean is how words are borrowed from other languages and made into Korean words. Many technological words have appeared in Korean form in recent years, just as many new words have been added to English and other languages.

Check the playlist for comparisons between the way of saying things in Korean and some other languages.

In a similar vein, the same new words are not always adopted in the same way in North Korea, as they are in the South. In many cases, the North Koreans adopt meanings (which is what the Chinese tend to do, as well), rather than sounds.

Japanese Spoken Language

Japanese (日本語, Nihongo) is the official language of Japan. It is often placed in the Altaic language family, though some linguists dispute this affiliation. Japanese shares grammatical similarities with the Korean language. Many words have their origins in borrowings from Chinese and more recently English and other Western languages. Like Korean, Japanese is an SOV (subject-object-verb) language. While Japanese is not a tonal language like Chinese, it does contain pitch accents (which affect the way parts of words are stressed). In all, there are 5 vowels and 13 consonants, far fewer sounds than in English or Chinese.

Hierarchy reflected in language

Both the Korean and Japanese languages reflect the deep hierarchical structure of their cultures. Both contain endings on verbs that change according to the relationship between the speaker and the listener. The language used reflects the level of politeness in a specific context. In a typical short conversation between a customer and a clerk in a shop, the customer uses the verb arimasu, whereas the clerk uses gozaimasu. These two verbs have the same meaning, but the clerk uses gozaimasu, the polite version, to show deference to the customer. This shows the proper social distance between the speaker and someone in a higher position of respect (by age or seniority) in a group. Similar distinctions would be made at a company, a school, etc.

Check the playlist for examples of Japanese formal and informal speech.

Speaking and harmony

Speaking and acting properly is of extreme importance in Japanese society in order to maintain proper harmony, called wa. Directness is not encouraged, and there is even a class of sounds known as “hesitation noises.” These are commonly used to indicate the speaker’s discomfort or hesitation to answer a question posed by the listener, and they are also used in order to seem indirect and soft in one’s speech style. They can even be spoken to allow the speaker time to collect his or her thoughts of how to phrase the correct response. These noises are something like saying “well…” in English, although they are much more varied and nuanced. The most common hesitation noise, “ano,” is used between two employees working in the same section of an office. One asks a question, and the other uses a hesitation noise to show his reluctance to answer too directly.

Terms of address

As with all East Asian languages, another marker of politeness is the use of titles and family names rather than personal names. Personal names are only used among close friends and some family situations. No student or young person would dare address a teacher, someone senior to them in rank, or someone they are unfamiliar with by his or her first name. The ending “-san” is added to the family names of persons who are addressed in public situations or between people with some social distance between them. Here are some examples of using family name plus title to address someone:

田中社長 Company President Tanaka/ Tanaka Shacho

山本先生 Instructor Yamamoto/Yamamoto Sensei

鈴木さん Mr./Mrs./Ms. Suzuki/ Suzuki-san

Name order

As in Chinese and Korean, the family name comes first when addressing someone in Japanese. For example, in the name Suzuki Yoko, Suzuki is the family name and Yoko is the personal name. However, it is common in the English language and other Western languages to convert Japanese and other East Asian names to the Western style of presentation. Therefore, the name Suzuki Yoko would be changed to Yoko Suzuki.

Gendered language

Another important cultural aspect of Japanese is that the words and style of language used by men and women can often vary significantly. For example, with a close male friend, a man may use the rough, direct first-person pronoun (meaning “I” or “me”) “ore,” rather than gentler alternatives like “watashi” or “watakushi,” which are more commonly used by women. They may also use more direct sentence-final particles, such as “na” or “zo,” or rougher forms of verbs, such as the blunter “kuu” for “eat” instead of the more neutral “taberu.” These would be examples of standard language between two male friends who have known each other for a long time and enjoy a close degree of friendly intimacy.

A woman speaking to a casual female acquaintance, on the other hand, would typically speak very differently. Women typically use politer, gentler forms even in casual conversation, such as saying “Onaka suite imasu ka?” instead of “Hara hetta?” to ask “Are you hungry?” By posing the question of “Are you hungry?” to the listener she would be showing that she is worried about how they feel, an important aspect of Japanese social interaction. Most likely, she is hungry herself, and her listener would understand this upon hearing the question.

Loan words

Japanese has many words with their origins in borrowed from other languages. Often these are words for things originally from other countries that were imported into or redeveloped in Japan. Many words from Chinese, Portuguese, German, English, and other languages have been borrowed over the centuries as Japan has encountered different cultures. Here are some examples:

| Japanese | Original language | Meaning |

| arubaito | German | part-time job/work |

| pan | Portuguese | bread |

| terebi | English | TV |

Recently an interesting phenomenon is the development of words that are of English derivation that have been “Japanized” and re-borrowed by English. These words include cosplay (originally from English “costume play”), anime (from “animation”), etc.

The Written Languages in East Asia

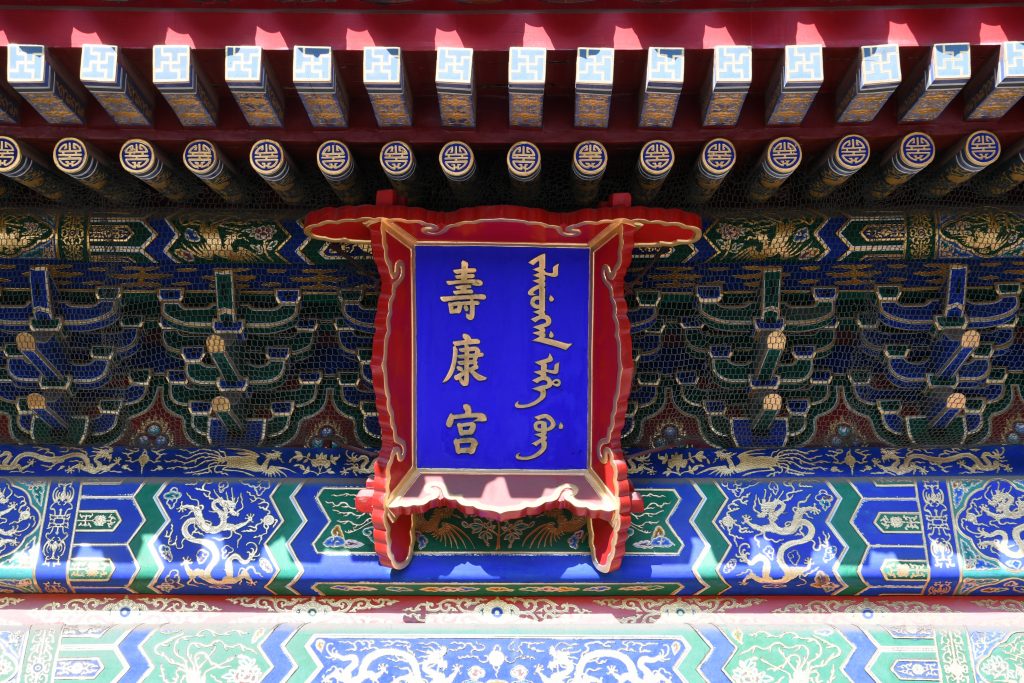

The Chinese Writing System

Spoken Chinese is a fascinating language to study and fairly easy to learn once the tones are mastered. The writing, however, is another story. The Chinese writing system dates to at least the Shang dynasty (1600-1100 BCE) and possibly into Neolithic times. The Koreans and Japanese later adopted the Chinese writing system though they eventually invented other systems to represent the sounds of their languages. However, due to this history, Chinese characters are still mixed in with the writings systems of South Korea and Japan.

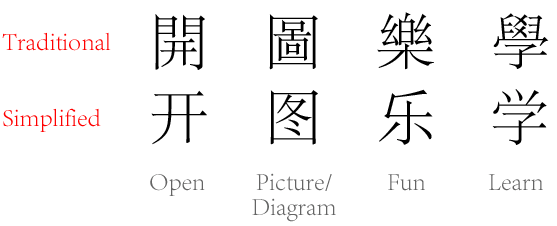

The Chinese writing system is based on characters (sometimes called graphs) that are composed of one or more of approximately 214 parts called “radicals” (bùshǒu in Chinese, literally “section headers”). Since there is no alphabet, it is necessary to remember all of the characters (called hanzi in Chinese) one by one. There is no reliable way to sound them out or spell the characters. Only memorization works—both for the sound and the meaning. Considering that there are over 40,000 characters and that a literate person needs to know about 3,000 words to conveniently read a newspaper, the learning task can be very daunting. Elementary school students spend great amounts of time memorizing how to read and write (and writing is even harder than reading!). To complicate things even more, soon after 1949, texts published in Mainland China began using simplified versions of about 1,800 characters, while texts in Taiwan (and Hong Kong) still use the older style. Persons who read materials from both areas need to be able to recognize both styles.

In some instances, an unfamiliar character may offer clues about its meaning or pronunciation—though these are never more than clues. One part of a compound character, that is, one with a “meaning” part and a “sound” part, can give clues about meaning. For instance, if the radical 木 (mù, “wood”) is used in a character, then the character may have something to do with a tree, as in the character 枝 (zhī, “tree branch”), 松 (sōng,“pine tree”), or 桥 (qiáo, “bridge” – traditionally built with wood). Radicals for herb (艹), metal (釒), water (氵), soil (土), mountain (山), hand (扌), eye (目), and sickness (疒) can also give clues about meaning. Other components of a character may hint at the character’s sound. For instance, the character 支 (“support”), pronounced zhī, is part of the character 枝, also pronounced zhī. The character 登 (“climb”), pronounced dēng, serves as the phonetic component in the character 瞪 (“stare at”), pronounced dèng, and the 目 radical in the character 瞪 gives a clue that the character has something to do with seeing. In fact, not all the phonetic radicals perfectly indicate the pronunciation of the characters. Sometimes the sound radical only shares the same vowel or the same consonant with the character’s pronunciation. Often there is no way to tell how a character is pronounced unless someone who knows the pronunciation reads it aloud, or another written system (like the Pinyin system discussed below) that can represent the sounds is used.

|

|

|

|

| (Character images for 泳, 氧, 聋, and 飢 from Andres Leo, chinese-word.com) | |

Though in general you cannot figure out a character’s meaning by looking at it, there are a few hundred of the characters that are representational—that is, they look something like what they mean. For instance, the character for “sun” at one time looked very much like a sun, but over the centuries became more stylized.

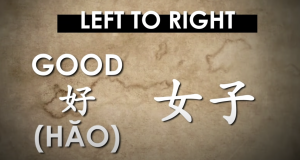

It is a myth that Chinese is a language of “ideograms” that always picture the ideas being expressed. In most cases, one has little or no idea what the character means unless one is told. It is also interesting that in many cases characters have more than one pronunciation and carry different meanings, which are determined by context and the structure of the sentences they are in. For example, when the character 好 is pronounced in the third tone as hăo, it means “good” or “OK” in English. But when it is in the fourth tone as hào, it means “hobby.” In Japanese, many characters have both a “Japanese” and a “Chinese” pronunciation (based on earlier, not modern, Chinese pronunciations). And it is also important to remember that many characters share the same pronunciation. For instance, 好 (“hobby”), 号 (“horn” or “number”), and 耗 (“to consume”) are all pronounced as hào.

Another complicating feature in the study of written Chinese is that there are two main styles. One is called Classical Chinese (which can be sub-divided into earlier and late styles) and is based on the earliest Chinese writings. Literally called “ancient Chinese” (gŭwén), writings in this style are very terse and formal—almost telegraphic. It has its own vocabulary, grammar and sentence particles that differ from known styles of vernacular (common) speech. Punctuations are not used and pauses between sentences and phrases are marked with particles. For centuries, Chinese officials used this style when writing documents, histories, imperial edicts, and so forth. It was a universal written language that could be read by speakers of any topolect, functioning in some ways like Latin once did in Europe. After about the 12th century, writings in a vernacular style much closer to actual speech began to appear in print. It was not until the early 20th century, however, that Vernacular Chinese (called báihuà) began to replace Classical Chinese in official documents. Today in China, only people who receive formal training in reading Classical Chinese can understand early Chinese documents or write in Classical Chinese style. Sample passages of many famous Classical Chinese essays are incorporated into textbooks for middle school and high school students and some aspects of the older style are still used in formal writings and newspaper headlines today.

Here is an example of a sentence written in Classical and vernacular Chinese:

|

Classical Chinese: |

孔子曰受业身通者七十有七人皆异能之士也 |

|

|

|

|

Vernacular Chinese: |

孔子说:“跟着我学习而精通六艺的弟子有七十七人,他们都是具有奇异才能的人”。 |

|

|

|

|

English: |

Confucius says: “I have seventy-seven apprentices who are following me to study and learn the Six Arts. They all have unique talents and capabilities.” |

By the late 19th century, Westerners living in China began developing ways to write the sounds of Chinese in Western alphabetic languages. The most famous of these early efforts was the Wade-Giles system, named after two missionaries. This system is still used by some scholars, although in recent years the system called Pinyin, invented in the People’s Republic of China after 1949, has been increasingly adopted by the media and scholars alike. Besides Wade-Giles and Pinyin, several other systems (both alphabets and syllabaries) are also in use in Taiwan and in teaching materials in the West. In some situations, spellings may be made up (the names of some Chinese restaurants, for instance). Thus, readers may encounter several different ways to romanize or otherwise represent the same sound that is represented by a single character. This is especially a problem when reading maps made on the mainland and Taiwan. Here are a few phrases in both Wade-Giles and Pinyin:

|

W-G: |

Hsieh-hsieh |

Thank you! |

|

Pinyin: |

Xie-xie |

|

|

W-G: |

Ni hau ma? |

How are you? |

|

Pinyin: |

Ni hao ma? |

|

|

W-G: |

Ch’ing tsuo. |

Please have a seat. |

|

Pinyin: |

Qing zuo. |

|

|

W-G: |

Teng Hsiao-p’ing |

Chinese leader’s name |

|

Pinyin: |

Deng Xiaoping |

|

Although some Chinese thinkers have suggested that someday an alphabet or syllabary will replace Chinese characters, advances in computer technology and an interest in and love for the characters seem to ensure their use for the foreseeable future.

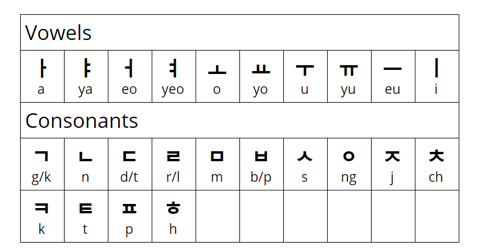

Korean Writing Systems

Like Japanese, the Korean writing system has a complicated history. The earliest writing system used by Koreans was the Chinese writing system, which was introduced to the Korean peninsula by about 100 CE. As Confucianism and Buddhism gained a foothold in the kingdoms of the peninsula, a class of scholars developed who took Classical Chinese (called “Hanmun” in Korean) as the standard written language. A few scholars and monks interested in Buddhism also studied Sanskrit. As time went on, some Korean scholars wished to have a writing system that would reflect the sounds of Korean. Early efforts involved taking select Chinese characters and using them for their sound value. One such system was called Idu. In the Idu system, one, two, three or more Chinese characters, called Hanja in Korean, would be used to represent the sound of a Korean word, completely disregarding the individual meanings of the Chinese characters. This system was very awkward and found only limited usage. A few poems in these Chinese-character based systems from Silla and Goryeo still exist.

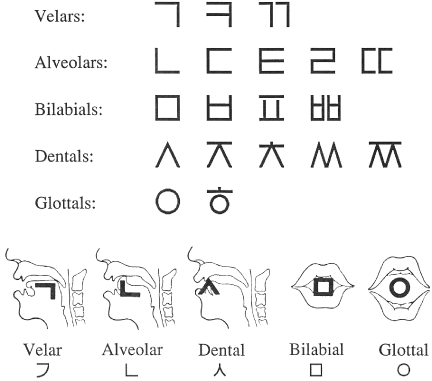

Finally, in the 15th century King Sejong asked his scholars to develop a system that was easy to use and learn and that accurately reflected the sounds of Korean. The result was the Hangul writing system. In some ways it is like the Japanese kana syllabaries (see below), though the shapes of the Hangul symbols are not derived from parts of Chinese characters. Rather, they are abstract representations of the shape of the mouth and position of the tongue when pronouncing a given sound.

Even though this efficient Hangul system was developed in the 15th century, it was not widely used by officials and scholars until the early 20th century. Instead, merchants and women adopted it for business purposes and literary expression. As time went on whole genres of literature written in Hangul developed (see Korean Literature). As Korea began to modernize in the early 20th century, the hanja (Chinese characters) used by the Confucian upper-classes were soon found to be inadequate for modern times. By 1950, Hangul was adopted as the official written language of both South Korea and North Korea. Although Korean can be written completely using Hangul alone, in South Korea, hanja are still used in some situations and are often mixed into sentences written primarily in Hangul. In North Korea, however, only Hangul is used for most writings.

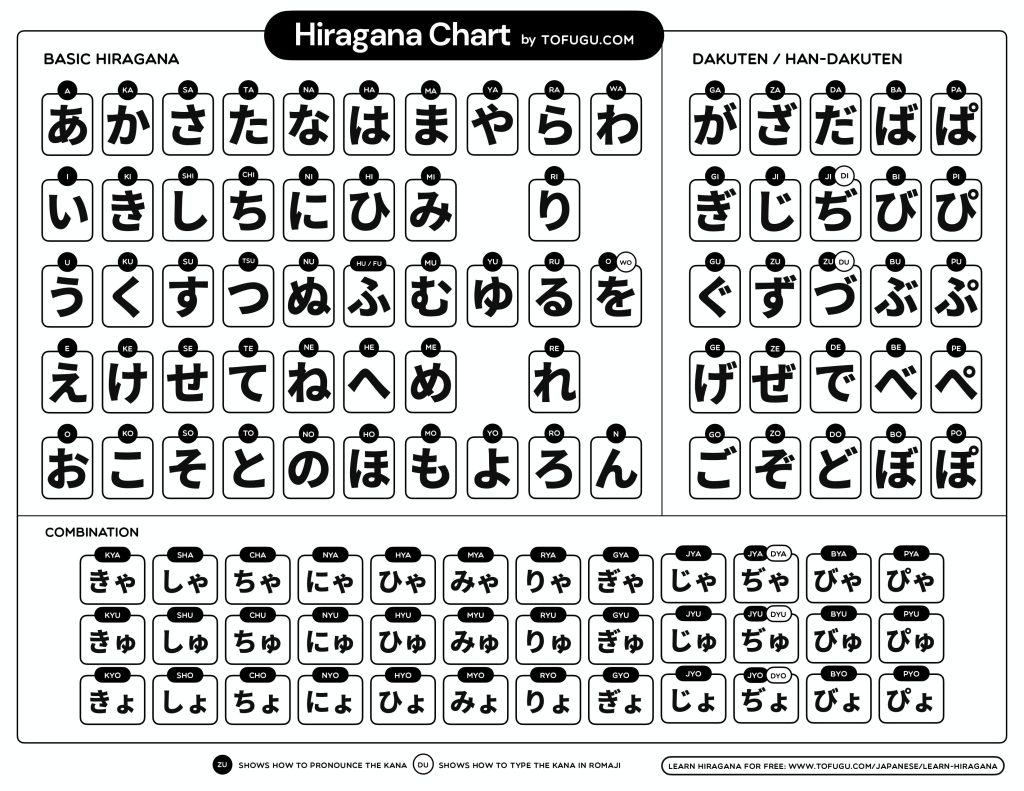

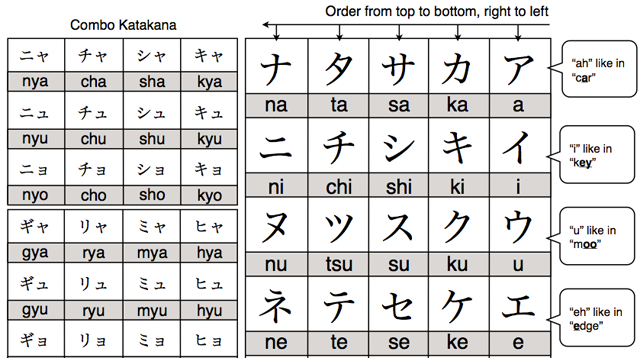

Japanese Writing Systems

By the 9th century the Japanese had developed a phonetic system called kana with which to write the sounds of their language. There are two kana systems: hiragana and katakana. Hiragana is used as detailed below to write the sounds of native Japanese words. Katakana is commonly used to write the sounds of foreign loan words (often Western ones like Portuguese, Dutch English, French, and German). Both systems are based on abstracted forms of the elements (radicals) that make up the construction of Chinese characters. Japanese is one of the most complex writing systems in the world. This is due to the merging of three distinct writing systems into one uniform system used to write modern Japanese. Chinese characters (hanzi in Chinese; kanji in Japanese) were introduced into Japan by the 6th century and became the first medium for writing and literacy. However, this system did not fit well because of differences between Chinese and Japanese language structure, and therefore Chinese characters were often given an additional Japanese pronunciation, most likely because there was no inherent sound value represented by the characters. The original Chinese reading of a character is reflected in what is called the onyomi, while the Japanese version is the kunyomi. As an example of this system, the word for “below” (pronounced as “xia” in Standard Chinese today), is pronounced in onyomi (reflecting an earlier Chinese pronunciation) as “ka” or “ge,” while the kunyomi, the indigenous Japanese pronunciation, varies.

|

|

Today, about 2,000 kanji (Chinese characters) are used with the kana (the two phonetic systems) as a mixed writing system (though all kanji can also be written in the kana phonetic systems). Below is a Japanese sentence with kanji (un-highlighted), hiragana (in green) and katakana (in blue). It’s meaning is “I like black tea, but I do not drink coffee very often.” The small font hiragana above the kanji is to show the pronunciation of the kanji using hiragana. Such sound notation is often seen in elementary school students’ and non-native speakers’ textbooks because the pronunciation of the kanji must all be memorized, not sounded out as in the kana syllabaries. The word “coffee” ( kōhī) is a loan word from English, so it is written in katakana (in blue).

紅(こう) 茶(ちゃ)はきですが、コーヒーはあまりみません。

Aside from the kanji and kana, systems of romanization (romaji) are used to write Japanese using the Roman alphabet. Today the most used system of romanization is the Hepburn system, which is used in most language textbooks and publications. Japanese words written with the Roman alphabet are also sometimes incorporated into Japanese sentences. Can you figure out which kana are used in this chart?

|

English |

Japanese |

Kana Spelling |

Hepburn |

|

Mount Fuji |

富士山 |

ふじさん |

fujisan |

|

Tea |

お茶 |

おちゃ |

ocha |

|

Pizza |

ピザ |

ピザ |

piza |

|

Roman Characters |

ローマ字 |

ローマじ |

rōmaji |

It should now come as no surprise why Japanese is often regarded as among the most complicated writing systems in the world. Like other scripts in East Asia, it is challenging but rewarding to learn.

Other Languages in East Asia

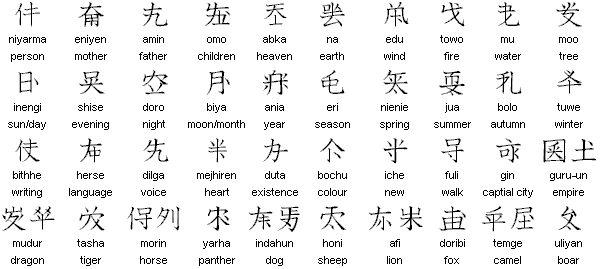

Besides Chinese, many other languages are spoken among the 55 ethnic minorities in China. Most of these languages fall into the following language families: Sino-Tibetan (such as Tibetan, Yi, Naxi, etc.), Ural-Altaic (Mongolian, Manchu, Uighur, etc.), or Tai (Zhuang, Dai, Dong [Gaem], etc.). Several of these languages also have traditional writing systems, and in some instances scripts were developed for languages now extinct in China like Xixia (Tangut). Since 1949, numerous romanization systems have been devised for contemporary languages, including Hani, Dong, Zhuang, Buyi, Daur, Yi, Miao, and Yao, all of which traditionally had no written scripts (or had ones with only limited usage among ritualists).

Among the traditional syllabic scripts are those related to ancient Middle-Eastern scripts, including Sogdian. These include early Uygur (Uighur) script, Mongolian, and Manchu (Manju). Written Tibetan and Dai, also syllabic, are related to Sanskrit and other scripts from ancient India. The written script used by today’s Uighur, Hui, and other Islamic minorities in China is Arabic. For a brief period, Khubilai Khan attempted to institute a syllabic script based on Tibetan script known as Phags-pa writing. He wished that all the peoples in his realm would use the system, but his plan eventually failed.

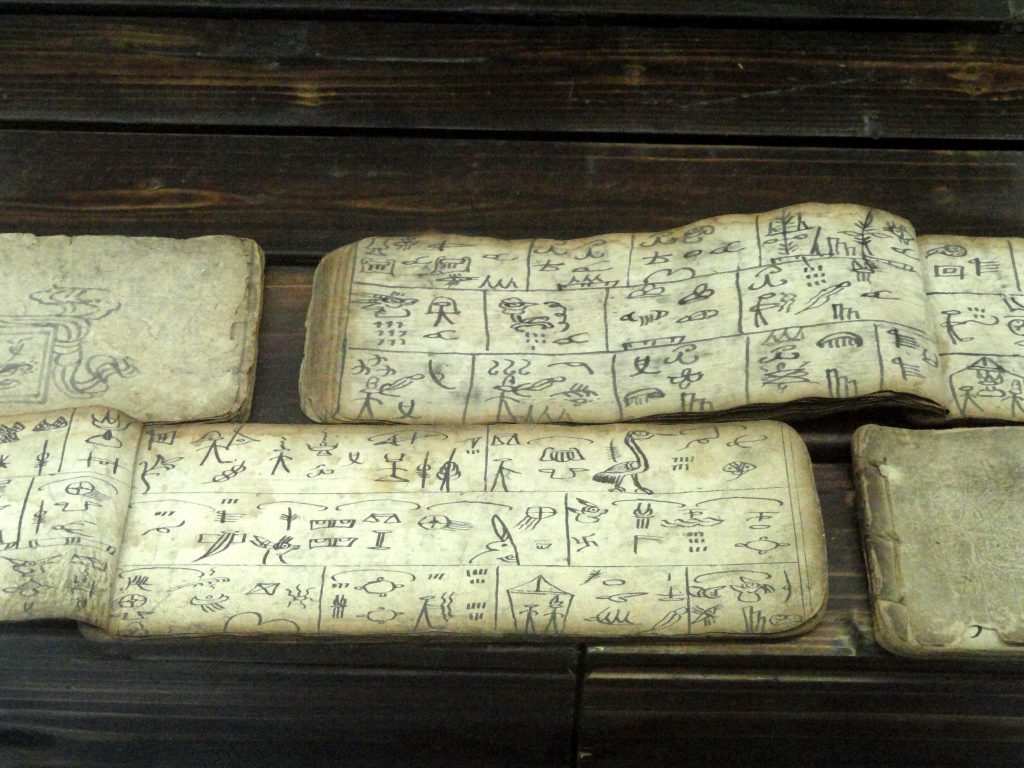

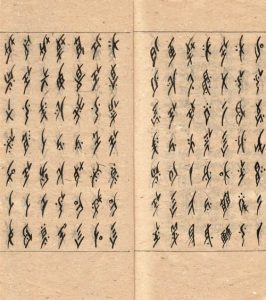

Besides Chinese, other scripts native to southwest China include the Yi script and the “dongba” writing system of the Naxi nationality. Both the Yi script (which consists of several related scripts) and the Naxi script were primarily used by ritual specialists to record songs, chants, and local history. The Naxi dongba script is cartoon-like and its graphs have become popular design elements among young people in some parts of East Asia. The Northern Yi (Nuosu) version of Yi script now has a modern, standardized syllabary of about 821 graphs and a corresponding romanization.

A lesson in standardized Northern Yi romanization and script, with Chinese and English equivalents:

va ꃬ 鸡 chicken

Ngat ax pu va yip zi ma hxo da

ꉠꀉꁌꃬꑍꊏꂷꉘꄉ.

我爷爷养了20只鸡.

My grandpa raised 20 chickens.

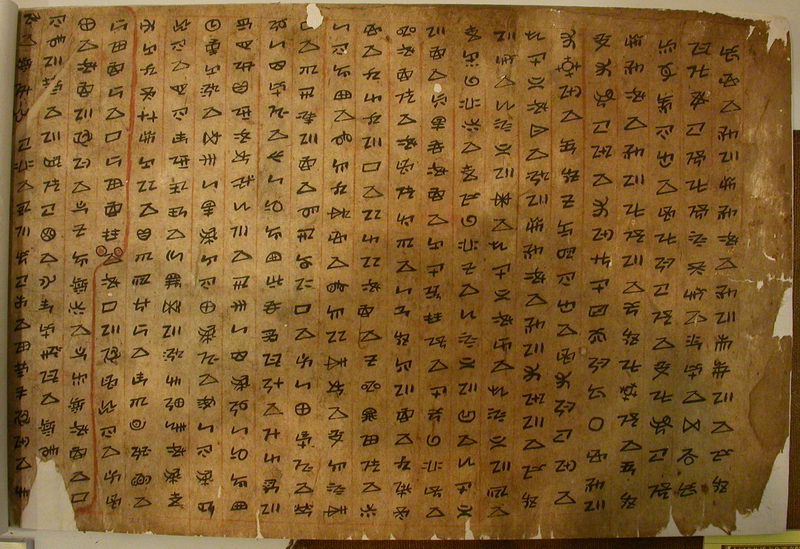

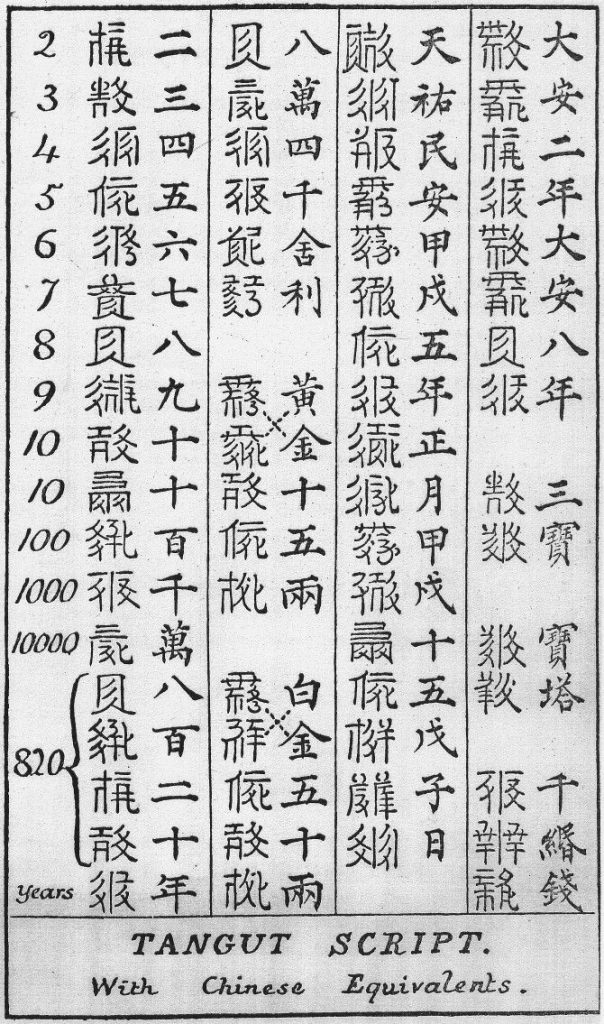

A pair of scripts that look very similar to Chinese characters was developed by the Tangut people of the small Xixia kingdom (in today’s Ningxia Hui Nationality Autonomous Region). The Xixia kingdom was destroyed by the Mongols in the 12th century and only a few examples of the scripts have survived the ages. Chinese scholars are still trying to fully decode the Xixia scripts. Another script that looks like Chinese was developed around the 13th century by the forerunners of the Manchu, the Jurchen (or “Nujen”/”Nuzhen”). Even though both the Xixia and the Jurchen scripts are superficially similar to Chinese graphs, unless one knows the scripts they are unintelligible to Chinese readers.

In Jiangyong county, a small area of Hunan province, a script called nüshu that was known only to women was developed (probably in the 19th century). It was used by women to write letters and record stories and its use has been revived in the tourist industry today for writing on fans, wall-hangings, and in cultural shows. Also, in a few cases in southern China, Chinese characters were once used for their sound value to write the languages of the Zhuang and Dong peoples, similar to the way the characters were used to write ancient Korean and Japanese.

Select Sources:

Ramsey, Robert S. (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

- Languages of China

- Korean

- Japan

- Comparing Languages