3 Module 2: Histories of East Asia

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

INTRODUCTION

This unit presents a historical overview of events in the history and cultural development of East Asia from the perspective of each area: China, Korea, and Japan. Each section begins with a discussion of basic themes in the history of the cultural area then outlines and details important events and cultural developments throughout history. The goal of this module is to present a more thorough portrait of each area, highlighting trends, events, historical figures, and timeframes that are useful in understanding each culture independently, and how each culture contributes to the idea of East Asia as a whole.

CHINESE HISTORY

PART 1: OVERVIEW

Chinese history is long and complex—with records dating to around 1600 BCE. Although the histories of Egypt and the Middle East are considerably older, cultural threads, exemplified in written language, architecture and other aspects of material culture, beliefs, and custom clearly link contemporary China to a distant past—more so than most contemporary cultures today. That cultural legacy has been at times a burden, but more often serves as a valued pool of philosophical, material, and spiritual traditions.

PART 2: THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY

Among the important themes that characterize Chinese history are the pattern of dynastic rise and fall, intermittent aggression from northern peoples beyond the borders, varying degrees of openness to outside cultural influences, and the dynamics of stability and social harmony. All these themes still bear on China’s stance and position in the world today. Being aware of China’s history and traditional culture will enable us to better understand events presently unfolding in the country.

Dynastic Rise and Fall

The Chinese record their own history as a succession of ruling dynasties that begins with the legendary Xia dynasty (2100-1600 BCE), and ends in 1911-12 CE with the formation of the Republic of China—which was soon followed by the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. A dynasty is a succession of kings or emperors of the same family line. Although by the Qin dynasty (221-207 BCE) officials were appointed—eventually by participation in an examination system—the role of emperor was hereditary, passed down in a succession that, according to Chinese ideals, was from father to son. In many cases, however, after an emperor died or abdicated other relatives, and, on a few occasions, even non-blood relatives occupied the throne. Although Chinese history is regarded as a succession of dynasties, during certain parts of Chinese history the land area we call China today was under the control of several different kingdoms. After the fall of the great Han dynasty around 220 CE, for example, China fell apart into many smaller kingdoms and was not reunited until over three hundred years later by the short, but powerful Sui dynasty (580-618 CE). During the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE), invading northern peoples set up the Jin and Liao kingdoms in northeast China, and a large kingdom of Tibetan-related peoples called Xixia existed in western China. Therefore, when thinking about Chinese history, it is important to imagine it as a complex picture of unity and disunity over an exceedingly long time span.

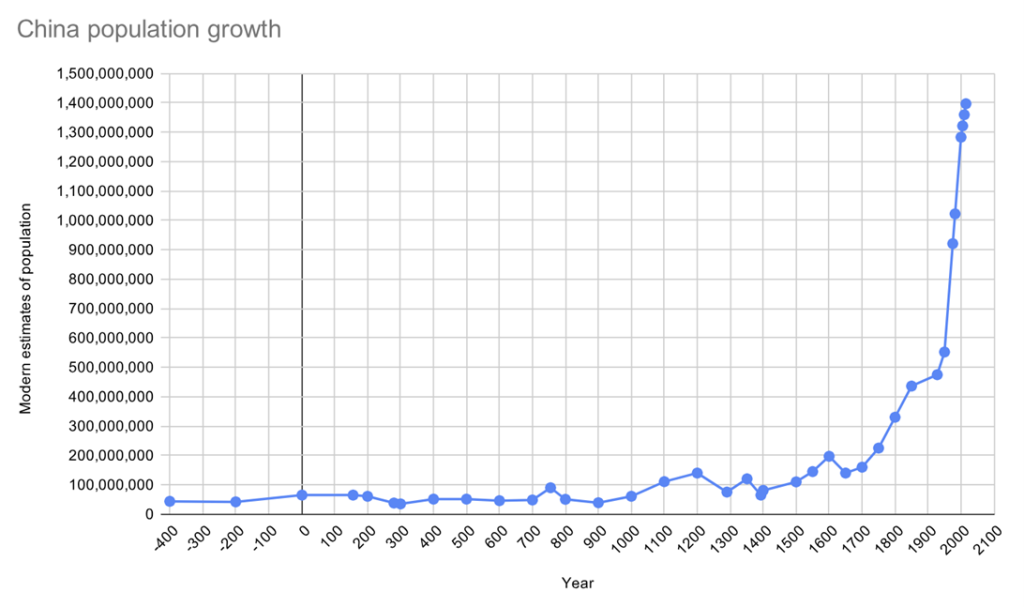

In a general sense, there was a pattern of dynastic rise and fall, often reflected in historical accounts, poetry, and other literature of China. According to the pattern, a dynasty follows 5 stages: 1) it is founded by force during a period of disorder; 2) vigorous rulers create a stable, prosperous state that secures or extends the borders; 3) after a period of success and stability (which often entails population growth), leadership declines, wealth concentrates into fewer hands, and the population outstrips resources; 4) the dynasty collapses due to internal uprisings—sometimes coupled with foreign invasions; 5) after a period of weakness and disunion, the cycle starts again with dynamic leadership (sometimes foreign, as in the case of the Mongols and Manchus), often in a climate of lowered population and redistributed wealth.

This theme of dynastic rise and fall resonates especially strongly in the Han, Tang, Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties. Many poets used allusions to patterns and events in past dynasties to comment on situations in their own times. Even today modern Chinese look back on their history as they attempt to make sense of their emerging nation.

Aggression from Northern Peoples and Other Non-Han States

Relations, often antagonistic, between nomadic Turkic and Mongol peoples of the northern steppes and forests and the settled agriculturalists of the North China Plain go back far into antiquity. Among the northern invaders were the Xiongnu and Xianbei, who were followed in later centuries by the Qidan (Khitan), Jurched, Mongol, Turk, and Manchu (Manju/Manzu) peoples. During periods of division, small states appeared and disappeared in northern China on the borders with the steppes. This was especially so between the Han and Tang dynasties. During this time many such states had mixed “Creole-cultures” that combined both steppe and sedentary cultures and lifestyles. Among these peoples was a group known as the Toba, whose descendants were among the founders of the great Tang dynasty.

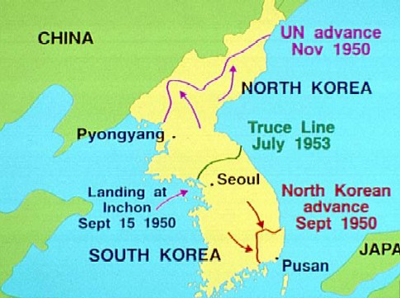

Besides the northern steppes and northeastern forests, alien states existed at times in other border areas. Among these were the Tibetan empire in the west, the Nanzhao in the southwest, the Tangut (Xixia) empire of the northwest (in present-day Ningxia), and the Uygur kingdom farther to the northwest in Xinjiang. Many smaller kingdoms existed as well, including the little-known Balhae kingdom located in parts of present-day northeast China and North Korea.

Nomads on the northern steppe depended on trade with the agriculturalists for grain, cloth, metal tools, ceramics, and other items. In turn, the agricultural peoples desired promises of peace from raiding parties and demanded tribute in the form of horses, furs, gems, and other rarities from the steppe and forest nomads. In the course of diplomatic negotiations, Chinese states sometimes sent beautiful women from aristocratic or even from the imperial family as brides to far-off “barbarian” rulers on the steppe. One of the most famous was Wang Zhaojun of the Han dynasty, who lived many years among the Xiongnu. Her tomb mound lies near the city of Hohhot, Inner Mongolia.

In some cases, Chinese rulers attempted to play rival groups of “barbarians” against each other; at other times, the border peoples created alliances to attack China. When the Mongols invaded China they had to defeat the Jin, who had already conquered the northern part of the Song dynasty, as well as the Xixia kingdom in the northwest.

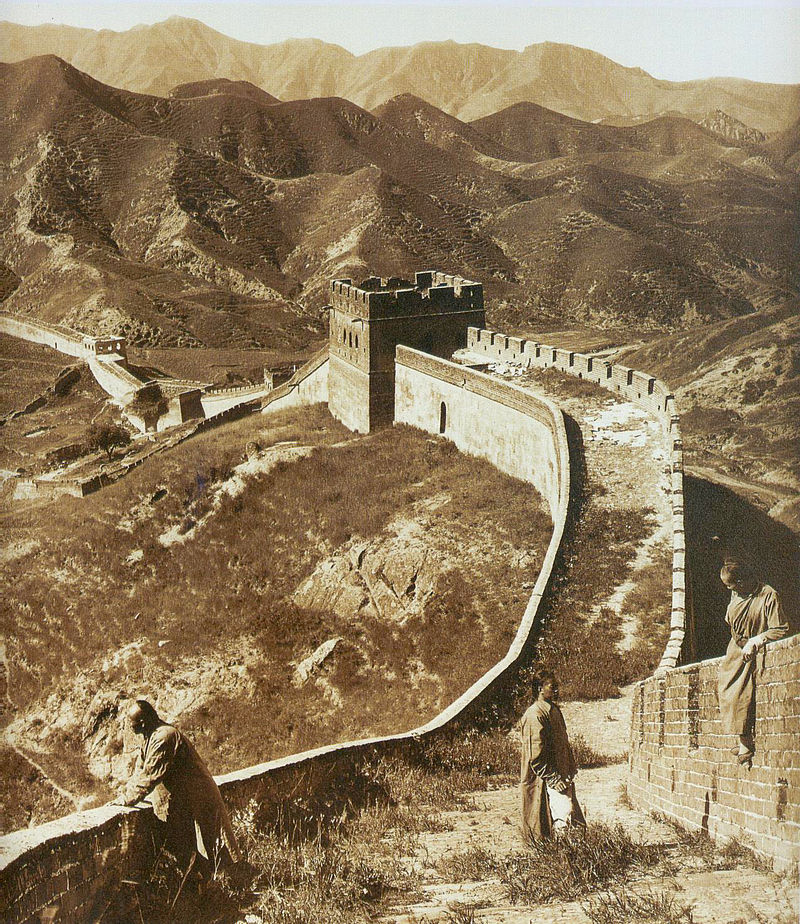

At certain moments the nomadic peoples feared the strong Chinese armies, at other times the steppe people offered great enough challenges to the Chinese to stimulate the building of walls on the northern frontiers—culminating in one of the greatest military projects of antiquity: the Great Wall. The wall, actually a series of smaller walls, reached its most advanced state during the Ming dynasty after the Mongols were driven from China.

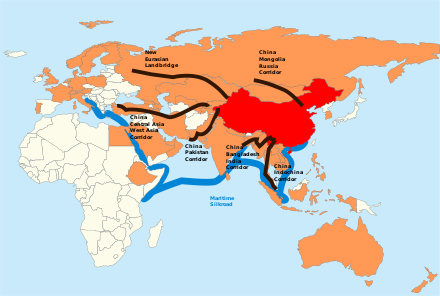

Degree of Openness to the Outside

Due to its geographical location, China could limit contact with the outside world. Aside from the northern nomads (who were not a cultural threat to the Chinese), the deserts and mountains of the west and the oceans of the east allowed the Central Kingdom relative (and often peaceful) insulation from entities such as the Roman Empire, which was at its height during the Han dynasty. The Silk Road was a narrow thread across the northwest barrens that allowed a limited but steady flow of goods and ideas back and forth across Central Asia between the high cultures of the Mediterranean, the Middle East, India, and China. During the Tang period, China was at its most open stance in antiquity. Elements from the cultures of the West, particularly India, were welcomed and took root within China’s borders.

After the Mongol invasions of the 13th and 14th centuries CE, China was for the first time under complete foreign control. When the Mongols were finally driven out in the mid-14th century, the Han Chinese rulers of the new Ming dynasty were, not surprisingly, warier of foreign influences than emperors in the Tang period had been. By the mid-15th century, the Chinese had made voyages to the coast of Africa, but in an inward turn the Chinese ships of exploration were ordered burned by the emperor and the Great Wall was refurbished.

As China began to lose ground technologically to the West, the Manchus (a people from the northeast) invaded in 1644. Less than a century later, the British were warring with China to force the country open to its trade in opium, with rights to peddle the drug within China. By the turn of the 19th century, China was in danger of being cut to pieces by Western and Japanese imperialists. Over the centuries, ambivalence towards foreign contact developed. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the principle of “taking what is best” from the outside was developed in an effort to import positive things from the West while at the same time keeping out foreign influences thought to weaken or humiliate China and the Chinese people.

The most recent expression of this ambivalent open/shut dynamic was the near-total closure of mainland China to much of the outside world between 1949 and the late 1970s. Feelings derived from negative experiences with foreign contact still linger under the surface in China today.

Concerns of Government Stability

As is explained in more detail in Module 3, social harmony was a key component of the ideas of Confucian statecraft. According to this belief, if rulers and subjects alike acted in proper accord with their inherited positions and prescribed familial roles, all would be well with the realm. It was up to the ruler to set an example by behaving properly in order to preserve the supernatural permission—or right to rule—that had been granted to the dynasty. This was known as the Mandate of Heaven. If a ruler was out of sync with the heavens, then society was sure to follow suit. What was feared most in this ideal system was instability and chaos. Instability was the result of any number of factors, including famine, invasion, unfair conscription of laborers and troops, over-taxation, and incompetent, corrupt, or malicious rulers. When conditions become unstable, popular uprisings can result, which may prove difficult or impossible to quell.

According to legend, the empire of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi, was brought down by a popular rebellion ignited by a group of workers on the Great Wall. Delayed because of a rainstorm, they were sentenced to death—but chose rebellion instead. In the first half of the 20th century, popular uprisings lead by Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalist Party brought down the Manchu government. Not long after, other popular forces, led by the Communists, took advantage of chaos within China caused by a weak central government, local warlords, and foreign invasion, to bring their movement to power over most of the territory in 1949. During the rule of Chairman Mao Zedong, particularly from 1966 to 1976, young minds and emotions were whipped into widespread chaos that endangered the stability of the country. Today, with an eye to the past, Chinese leaders must consider the effects of their policies in terms of state stability.

PART 3: PREHISTORIC ERA

Prehistory

|

|

|

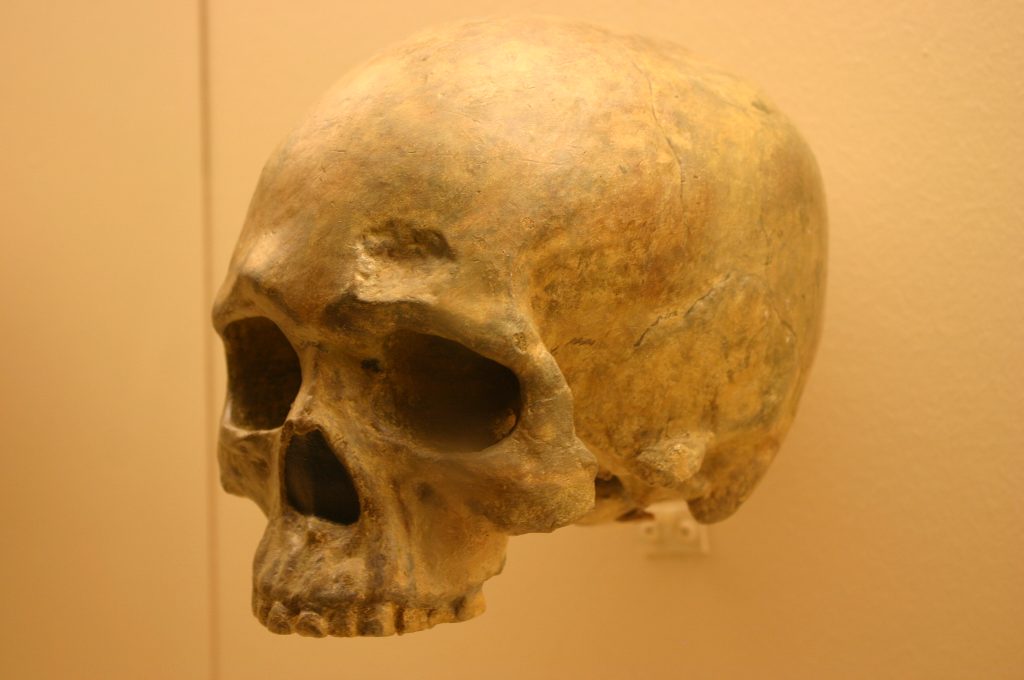

(Left) Bone fragments from a Peking Man skull. (Right) Liujiang Man’s fossil skull, found in Liuzhou, Guangxi. (Center) Artist rendering of “Dragon Man,” based on a huge skull found in northeast China near Harbin. |

||

Evidence of early hominids has been found at several archaeological sites in northern and southern China. The most famous of these is the so-called “Peking man” (once labeled Sinanthropus pekinensis), who seems to be a variation of Homo erectus, a widespread hominid who lived between one million and 250,000 years ago. Besides Peking Man (now called “Beijing Man”), similar fossils were found near Lantian in Shaanxi and near the city of Liuzhou, in the mountains of Guangxi. A number of sites with stone tools from early Homo sapiens have also been discovered in northern China, though the exact relation between these early modern humans and the Chinese people is still being examined. In 2021 a possible new human species, called “Dragon Man” (Homo longji) based on a large skull dating between 150,000 and 300,000 years ago, was made public by Chinese archeologist Ji Qiang. Some scientists have speculated the skull is that of the mysterious Denisovan human (an Asian contemporary of Neanderthals and early modern humans), though DNA testing may prove it to be a new species,

Neolithic, or “New Stone Age,” cultures featuring early forms of agriculture, weaving, advanced stone tool technology, village organization, and ceramics date to at least 6,000 BCE in China.

The best-known Neolithic sites are in northern China in the Yellow River drainage and include the famous “Banpo Village” site near the ancient city of Chang’an (modern Xi’an). The village was surrounded by a protective ditch that enclosed a number of round-shaped earthen pit dwellings and a pottery-making center.

Banpo village was a part of a larger agrarian culture called “Yangshao” that existed in the North China Plain and is characterized by unglazed yellow and red-colored pottery. Farther to the east, around the Shandong peninsula and farther south along the coast, was another early culture known as “Longshan.” Longshan culture was in many ways similar to Yangshao, though it is identified with a style of black pottery. Both the Yangshao and Longshan potteries are important examples of the earliest Chinese pottery.

|

|

|

(Left) Yangshao pottery. (Center) Banpo Village Neolithic site in North China. (Right) Longshan pottery. |

||

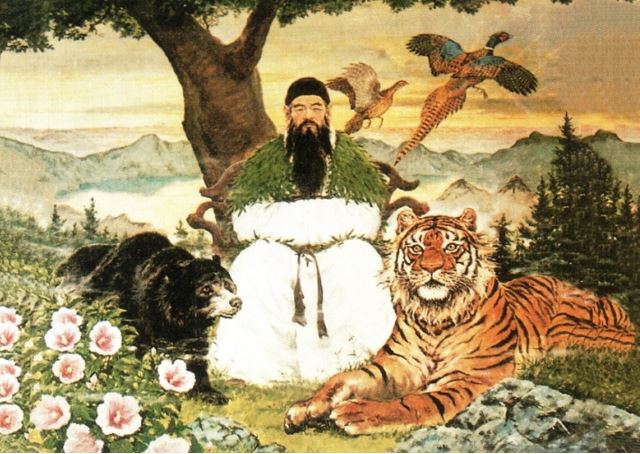

Myth and Legend

Each cultural area in East Asia has mythical accounts of the creation of heaven and earth, human beings, and civilization. Records of Chinese creation myths date to the Han dynasty (though certain elements may be much earlier). According to the accounts, in the earliest times there was undifferentiated murkiness. As things progressed, the light-weight substances rose and the heavy settled, resulting in the heavens and earth. The body of an early being, Pan Gu, metamorphosed into a myriad of things, and thus the earth gained geographical features and was populated with plants and animals.

Among the early beings were the male Fuxi and the female Nuwa. Nuwa is credited with creating the first humans out of clay and Fuxi is said to be an early ruler. Other early rulers followed, including Shen Nong, who invented the plow and agriculture and the Yellow Emperor, who invented pottery and the civilizing technology of writing.

The early rulers Yao and Shun were regarded as model emperors because of their dedication to proper principles of succession and governing—with an emphasis on good leadership. Their successor was Yu, who is said to be the founder of the legendary Xia dynasty, supposedly founded in 2205 BCE. Both records from the Shang dynasty and archeological evidence suggest that Xia may have actually existed on the North China Plain, although teams of archaeologists have been searching for its remains for decades. No conclusive findings have been made, though Xia and Shang may have both been related to earlier Yangshao and Longshan cultures.

|

||

|

|

|

Han dynasty wall paintings and a Qing dynasty woodblock print of legendary figures: (upper left) Nu Wa and Fu Xi, holding a compass and a square; (upper right) Shen Nong, who tested hundreds of kinds of herbs to determine their use by humans; (lower left) Emperor Yao, a sage ruler who gave his two daughters to his successor Emperor Shun in marriage; (lower right) Emperor Yao’s daughters Ehuang and Nuying. |

||

PART 4: EARLY FEUDAL ERA

Shang Dynasty (1600-1100 BCE)

Like the Xia, the Shang dynasty was known only from historical records, until archaeologists uncovered ruins and tombs of the ancient Shang capital near Anyang in northern Henan province in 1927. Found also were over 100,000 animal scapulae and tortoise shells engraved with approximately 3,000 different written characters in the so-called oracle bone script. These are the oldest documented examples of fully-developed Chinese writing.

Historians today feel that Shang culture was likely similar to that of the earlier Xia kingdom and centered on dynasties of kings who presided over rituals and ruled over villages of peasant farmers. Remains of large tombs, and altars made using rammed earth technology (walls and foundations made by ramming wet earth within large molds—a practice still used to make adobe dwellings in parts of China today), indicate a high degree of social organization, as this was needed to produce these structures.

Writings from the Han dynasty indicate that there were 30 Shang kings, and that succession was passed from elder to younger brothers as well as from father to son. Shang beliefs seem to have centered on ancestral spirits and a god known in the records as Shangdi, or “upper ruler.” The ruler was thought to have direct links to the powers on high. Rulers presided over a number of ministers who helped direct affairs of the palace, the realm, and ritual, as well as ranks of civil and military officials. Although rulers were typically male, Fu Hao, the wife of one ruler, is said to have been one of Shang’s most able military generals.

|

|

|

|

The tombs at Anyang indicate that sacrifice to the heavens and ancestors were an important part of Shang ritual life. Among the grave goods are sophisticated bronze ritual vessels, which were skillfully cast in clay molds using techniques first developed for pottery production. A common artistic motif on the bronzes was the “glutton” or taotie—a kind of supernatural beast with gaping jaws (see the design in the photo above). Offerings of food and drink were placed in these vessels during rituals. Many remains of human sacrifices have also been uncovered from the tombs at Anyang, including a few skulls with more Western features. Chariots uncovered in the tombs suggest at least indirect contact with Mesopotamian cultures.

In recent years Chinese archaeologists have uncovered several other early sites in southwest China. The Sanxingdui (Three Stars Cache) site near Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, may have been contemporary with Shang. The site is noted for its large assemblages of bronze objects that are quite unlike those found at Shang sites. Of note are hundreds of stylized bronze heads—many broken, some covered in gold leaf—and existing in various sizes. Most outstanding is an abstract, life-size image of what seems to be a ritual specialist. The findings at Sanxingdui and nearby sites raise more questions about early cultures in China than they answer. But one thing is clear. As research continues, a fuller picture of the early origins of Chinese culture will emerge.

|

|

Zhou Dynasty (1100-221 BCE)

The Shang dynasty gave way to another kingdom called Zhou in 1100 BCE. The Zhou were once part of the Shang realm, and were located on the northwest borders near present-day Xian. Referred to as “barbarians” in early accounts, the Zhou seem to have conquered the Shang with a force of only 50,000 warriors after armies of the degenerate and oppressive Shang king joined the invading forces. Early rulers included King Wen (the “Cultivated”), who helped lay the foundation for the Zhou victory, and his son King Wu (the “Martial”), who carried it out. These two rulers embodied dual aspects of Chinese leadership incorporating both civil and martial strengths that would remain relevant for centuries.

Once Shang resistance was squelched by King Wu, a new order was put in place that evolved into a feudal system in which a central Zhou state developed relationships (by blood or marriage) with local lords all over the former Shang realm. Military prowess and accomplishment remained important attributes among the upper classes. Most people were farmers, and therefore serfs to various levels of local lords. There were also classes of craftspeople and traders.

The early period of conquest and rule, called the Western Zhou, produced another exemplary leader named the Duke of Zhou. The Duke was instrumental in forming an efficient bureaucratic state and later in the Zhou period, the sage Kongzi (Confucius) held him in high regard for his proper conduct. According to this story, the Duke of Zhou was the brother of King Wu and upon Wu’s death was made regent for his son. After years of giving good advice and guidance to the future heir to the throne, the Duke of Zhou “did the right thing” and stepped aside when the young king was ready to assume power. Although he probably could have wrested the kingship for himself, the Duke of Zhou demonstrated that proper conduct (li) and virtue (de) were more important than personal ambition.

By 771 BCE the Western Zhou had weakened due to natural disasters and ineffective leadership, finally collapsing under pressure from combined forces of western nomads and native Chinese. A popular legend tells that the last Western Zhou King would light signal fires to entertain his favorite concubine. In something like the “boy who cried ‘wolf’” story, he lit them one too many times, and the western part of the realm was overrun.

Under a new king, Zhou forces reconstituted themselves in the eastern capital called Luoyang, in present day Henan province. One era of the new Eastern Zhou dynasty was known as the “Spring and Autumn” period (770-476 BCE), famous for literature and rich philosophy, including the “Hundred Schools of Thought.” Confucianism, Daoism, Moism (Mohism), the Yinyang School, and many other philosophies flourished in this period. Classic writings and compilations like the Daoist classic, the Daodejing, the Analects of Confucius, the Book of Songs, and Sunzi’s Art of War all date to this period. This was an age of cultural and philosophical development that later ages would see as the true cradle of Chinese civilization.

An important idea in Chinese statecraft that had evolved early in the Zhou era was refined in this period. Thinkers such as Mencius (Mengzi) explained that under the so-called “Mandate of Heaven” only good rulers could receive the mandate (permission) of heaven to rule. If a ruler acted in accordance with the will of heaven, he would then remain in power and continue to serve for the benefit of the realm. If he failed in his duty, then the mandate would be withdrawn, and another ruler would come to power. Implicit in this formula was the peasant’s right to rebel if life became too intolerable. The early Zhou rulers used this theory to legitimize their usurpation of the Shang. In later ages, the theory would be invoked many times to justify dynastic and government takeovers in China. The social structure also underwent change during the Zhou. The Zhou kings were weak, and many local states evolved into nearly independent powers. Social mobility was also greater, and the influence of powerful families closely related by blood to the rulers declined. Systems of land tenure changed as well, with peasants paying taxes (rather than just labor) to their lords and the development of freer exchange of land. Metal coins became widespread in an economy that involved extensive and increasingly complex trade networks. Technological innovations saw the increased use of cast iron in place of bronze, which allowed for advances in the mass production of farm implements and of weapons—resources that would come into play in the final era of the Zhou dynasty.

|

|

|

This last era of the Zhou was known as the “Warring States” period (475-221 BCE). During this time, the individual Zhou states (which had their own armies) began full-scale struggles for power to rule and strategically ate each other up. By the end, only three states (Chu, Qi, and Qin) remained out of an original total of about seventy. The winning state was Qin. Located in the northwest, near the old Zhou homeland, the Qin had experimented with the principles of Legalism (fajia), which were promoted by the philosopher Han Feizi (d. 233 BCE). Unlike the program of Confucius, Legalism distrusted human goodness, and relied instead on bureaucratic theories of organization enforced by strict codes of rewards and punishments. With the final collapse of the Zhou feudal system, Legalist principles were implemented in the establishment of a unified empire under the leadership of China’s first emperor, Qinshi Huangdi.

Qin Dynasty (221-207 BCE)

Although the Qin was the shortest of the major Chinese dynasties, it marked a transition point between the weakly-centered feudal states of the Zhou era and the emperor-centered imperial states of succeeding dynasties. Innovations in the Qin laid the foundation for government structures that lasted, with some modification, down into the early 20th century, ending with the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911-12, 2,000 years later.

When the forces of Qinshi Huangdi, under the guidance of the Legalist thinker Li Si, took control of the Zhou territories, methods were employed to secure control over the realm. Setting himself up as an all-powerful emperor, Qinshi Huangdi’s authority was absolute. Hereditary blood-ties were no longer a part of officialdom, and each position in the newly created state bureaucracy could be filled as if moving individual pieces on a chess board. Local officials were strategically placed in areas where they had no local allies, requiring them to look to the emperor, rather than personal or local ties, for support. Weights, measures, and written characters (which at the time had many local variants) were also standardized so that officials in all parts of the land could easily read all documents. The widths of cart axles were standardized so that any cart could run on any of the earthen roads throughout the land, thus increasing the speed and efficiency of transport and taxation. The old states were also re-divided into provinces and prefectures under the control of appointed officials, while the surviving ruling families were ordered to the capital to deprive them of power.

Other attempts at control included the burning of all but one copy of each of the Confucian writings (213 BCE). Though books on technical subjects were spared, more books were lost in the chaos at the end of the dynasty. Thus, much of the early learning was lost, though after the emperor’s death many books were recovered from surviving scholars who had memorized them by heart. Legend also says the emperor ordered several hundred Confucian scholars, seen as subversive to the new order, to be buried alive. Many other stories exist of the cruelty and excess of Emperor Qin.

Hundreds of thousands of farmers were conscripted to work on public works projects, the most ambitious being a series of walls across the northern frontiers. The tale of Meng Jiangnu, who searches for her husband’s bones along the Great Wall, is one of China’s most enduring folk tales. Conscripted labor also built a massive tomb for the emperor near the modern city of Xian. Five huge armies of life-size terra-cotta warriors and horses were arranged around the tomb to guard the emperor in death. The tomb itself has yet to be opened by Chinese archaeologists, who wish to perfect their techniques before attempting to excavate a structure that legend says contains a detailed model of heaven and earth, complete with jeweled skies and mercury lakes. After the discovery of the terra-cotta armies in the late 1970s, a huge museum complex has been opened to the public, where hundreds of thousands of visitors can view the excavated remains of China’s first great empire.

That empire came to an end soon after the emperor died while on a tour. Legend says that his decaying body was covered with fish on the journey home so that news of his death would not spread. Uprising and rebellion soon followed, however, and none of his weak young successors were able to hold onto power. This ultimately ushered in the rise of the great Han dynasty, China’s first long-lasting empire, based on many of the principles developed during the Qin.

Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE)

The majority ethnic group in China today is called the “Han” (Hanzu, or “Han nationality” or “Han ethnic group”). The name derives from this first great empire, which lasted over four hundred years at about the same time as the Roman Empire (though the two empires knew very little about each other’s existence). The Han empire was founded in the chaos after the fall of the Qin by a rebel leader known as Liu Bang, also known by the reign name “Han Gaozu” given after his death. The early years of the Han were occupied with the consolidation of power. At the start, power was shared to some degree with local kings, but as time went on and the bureaucracy was revitalized along lines similar to the Qin, the emperor’s power grew. Legalist theory was also gradually replaced by a revitalization of Confucianism. This eventually resulted in the strengthening of the role of the emperor or “Son of Heaven” and in a more moderate state regarding what we would call “human rights” or “social justice.” Social classes included the ruling imperial family, civil bureaucrats, landed gentry (who acted as small-scale local leaders), farmers, artisans and craftspeople, and merchants.

Cast bronze mirror from Eastern Han dynasty, 100-200 CE. According to the description of this museum exhibit, “Depicted on the mirror back are two Daoist deities: the King Father of the East (Dongwanggong) and the Queen Mother of the West (Xiwangmu). Completing the design are the White Tiger of the west (one the Four Spirits representing the four cardinal directions, including the Green Dragon of the east, the Red Bird of the south, and the Dark Warrior of the north) and a chariot drawn by three horses. The reason for the redundancy of two symbolic images relating to the west is not known.” Such mirrors were common in ancient China. The opposite side is smoothly polished. They could have daily life or ceremonial usages. (Photo courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art, gift of Drs. Thomas and Martha Carter, licensed under CC0)

Great advances were made in intensive agriculture, including crop rotation, fertilizers, and new techniques in the use of draft animals. Town and country were linked in a more advanced agrarian economy, and many farmers pursued sideline activities such as textile production. There were also attempts (not always successful) to keep tax burdens on peasants low. This was done in part by creating state monopolies on high consumption essentials such as salt, iron, and alcohol in order to temper the growing economic wealth of the merchant-class. Graves of the Han dynasty gentry class offer a wealth of insights into everyday life, for interred with the dead were clay models of everything from houses of the prosperous and ample kitchens, to well-stocked courtyards and nursing farm animals, all made to scale.

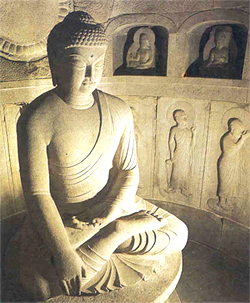

The borders of the Han grew, with advances along the Silk Road towards Central Asia, and large-scale migrations into southern China.After the founders, the greatest Han emperor was Wudi, who reigned from 141-87 BCE. The role of the emperor as a model of virtue who worked for the good of the people was expanded under his reign. Confucian philosophy also advanced, including the idea offered by the Han philosopher, official and writer Dong Zhongshu that nature would send signs such as earthquakes or floods if a ruler was losing the “Mandate of Heaven,” and speculated on the inter-relations between the heavens, earth, and mankind. In 124 BCE, an examination system was set up that offered an opportunity to males of any respectable background to elevate their (and their families’) positions in life. The exam system also served as a way to recruit true talent into the system. Much of what we know about early Chinese history comes from the writings of the historian Sima Qian (died c. 85 BCE), who was so dedicated to researching and editing the surviving writings of the past that he accepted castration for displeasing the emperor, electing to remain alive to finish his history rather than to commit suicide, which was seen as the more honorable path. Buddhism arrived from India by the first century BCE and gradually grew in popularity.

Throughout the Han era the Xiongnu on the northern borders were a threat dealt with first by warfare and then by a policy of diplomacy and appeasement that included Chinese brides. Under Wudi, the borders were expanded in a series of wars against the Xiongnu and command posts were established on the Korean peninsula in 108 BCE.

As time went on, however, the wars with the Xiongnu and other border peoples grew costly, lifestyles at the court grew lavish, and the tax burdens on the populace increased. After Wudi’s death attempts were made to rectify the situation, but eventually a usurper named Wang Mang came to power. He was the nephew of Empress Wang—one of a number of women who held powerful, but temporary positions during the Han.

Once Wang Mang took over the throne, he attempted to institute social reforms by taking from the rich and giving to the poor. His reforms included the re-division of landholdings, freeing of slaves, providing social welfare and revolving credit programs for farmers and the poor, taxes on the use of firewood and natural resources, and reinstitution of government monopolies on certain goods. In practice, most of the reforms were not effectively instituted, or had the effect of adding even greater economic pressures on the populace. He also launched costly, disastrous campaigns against the Xiongnu.

Eventually both the upper-class gentry and the greater population vehemently opposed the attempted reforms. As the young government became increasingly destabilized (possibly due in part to a traumatic shift in the course of the Yellow River in northern China), popular revolts led by a group called the Red Eyebrows brought the death of Wang Mang and an end to his experimental rule. The historian Wolfram Eberhard notes that Wang was decapitated while reading ancient scriptures in his chambers, and his skull was preserved for two hundred years.

After Wang’s death, the Han dynasty was revived by surviving members of the Han imperial line and returned to its former glory, though the capital in Chang’an (modern Xian) was moved eastwards to Luoyang. By about 189 CE, however, the realm was again on the road to crisis and collapse. Wars with border peoples like the Xiongnu and Xianbei, internal problems with powerful military cliques, weakening leadership at the imperial court, and more popular revolts—this time by groups such as the Yellow Turbans—fatally weakened the dynasty. It collapsed in 220 CE ushering in a period of disunity in China that lasted for about three hundred years. As Professor J.A.G. Roberts has observed, Rome fell at nearly the same time—and for similar reasons (especially pressure from nomadic peoples)—though Europe, unlike China, was never reunited in the same way again.

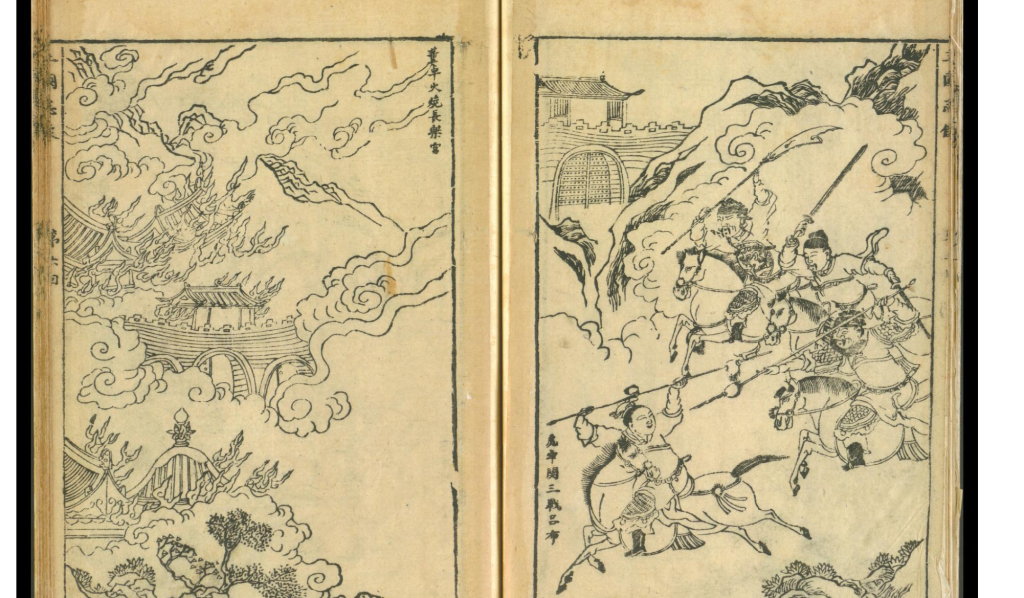

Period of Disunion and Alien Empires (220-581 CE)

With the fall of the great Han dynasty, the Middle Kingdom ceased to exist. For the next three and a half centuries numerous small kingdoms rose and fell on the lands that were once all ruled by the Han. First among these were three kingdoms, two southern ones called Shu Han (in present-day Sichuan) and Wu (in the Yangzi River basin), and a northern one called Wei. Battles and intrigues between the rulers of these states constitute the plot of China’s greatest historical romance, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi). The northern Wei state had a population of about 29 million, making it by far the largest of the three. Among its population were 19 groups of Xiongnu who had been allowed to settle in China near the end of the Han. There was relatively little encroachment on the northern frontier at first, since alliances among the nomadic tribes themselves had recently fallen apart and were yet to be reunited under a charismatic leader. During this period the Wei actually forged an alliance with the early Yamato state in Japan to attack hostile nomad groups on the Korean peninsula.

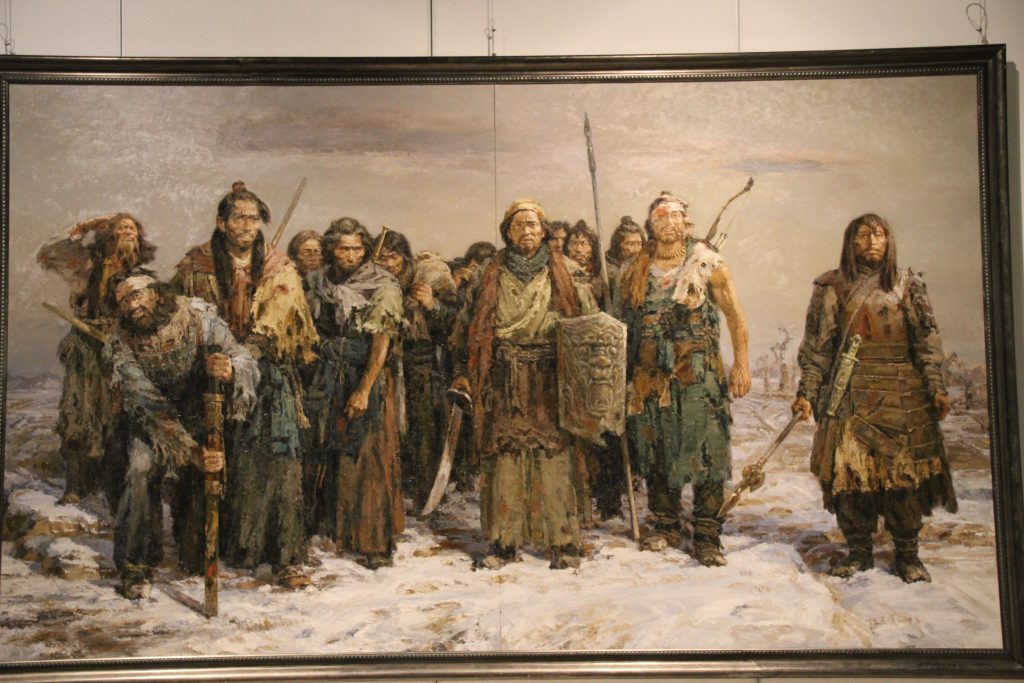

As time went on, these kingdoms collapsed, and large numbers of demobilized Chinese soldiers began farming and practicing various trades on the northern borders. In turn, nomads of Turkish, Xiongnu, Xianbei, Tibetan and other ethnic backgrounds allied and took control of adjacent areas. Cultures interacted over time, and a series of small states rose and fell. Some attempted to follow Chinese models of rule, many others gave their loyalties to charismatic rulers (a nomad attitude) whose kingdoms fell apart at their deaths.

During the 4th century a Tibetan leader created a large domain in western China. This was followed later in that century by a large state that ruled northern China and contiguous areas into the mid-6th century. The state was a multi-ethnic federation populated by the Toba people, whose leaders had adopted many aspects of Chinese tradition.

In the south there were fewer kingdoms, although cultural mixing between ethnic Chinese and southern indigenous peoples also took place. Northern immigrants were forced to adopt diets less rich in meat and higher in soybeans, fruits, and leafy vegetables as well as to adopt southern techniques of wet rice farming instead of the dry-land wheat production typically practiced in the north. In some instances, even the southern regions were subject to raids from the northern nomads.

Written records of the period of disunion are mostly from Chinese language source and were often composed by intellectuals in the service of “barbarian” overlords. The most important intellectual and spiritual trend of the long era was that of Buddhism and monks continued to enter the Chinese regions on both northern and southern trade routes.

PART 5: THE GREAT DYNASTIES

Sui Dynasty (580-618 CE)

China was finally reunited under the efforts of a capable and thrifty military leader from the northwest named Yang Jian, also known by the reign title Wendi. His dynasty would be known as Sui. Like the earlier Qin dynasty, the Sui was a short and severe dynasty that nonetheless garnered many accomplishments.

The Sui revitalized old connections throughout the empire and revived institutions of control that would be further embellished by the great and long-lived Tang dynasty that followed. Among the accomplishments of the Sui was the building of the Grand Canal that linked the thriving cultures of southern China with those of the north, near the new Sui capital at Luoyang. The canal acted as an inland watery highway, especially useful for the transport of grain.

Strains were placed upon the Sui treasury by wars with foreign peoples on the northeast border, including attempts to defuse an alliance between the Korean state of Goguryeo and their nomadic Turkic allies. Leadership also became a problem after Yang Jian’s son, Yang Guang, or known by his reign title, Yangdi, took the throne. Although he is responsible for the success of the Grand Canal, historians and popular literature have not been kind to Yangdi’s memory. A case study in imperial decadence, Yangdi was known for high living and lavish expenditures on parties, palaces, and lengthy trips through the exotic southern reaches of his realm.

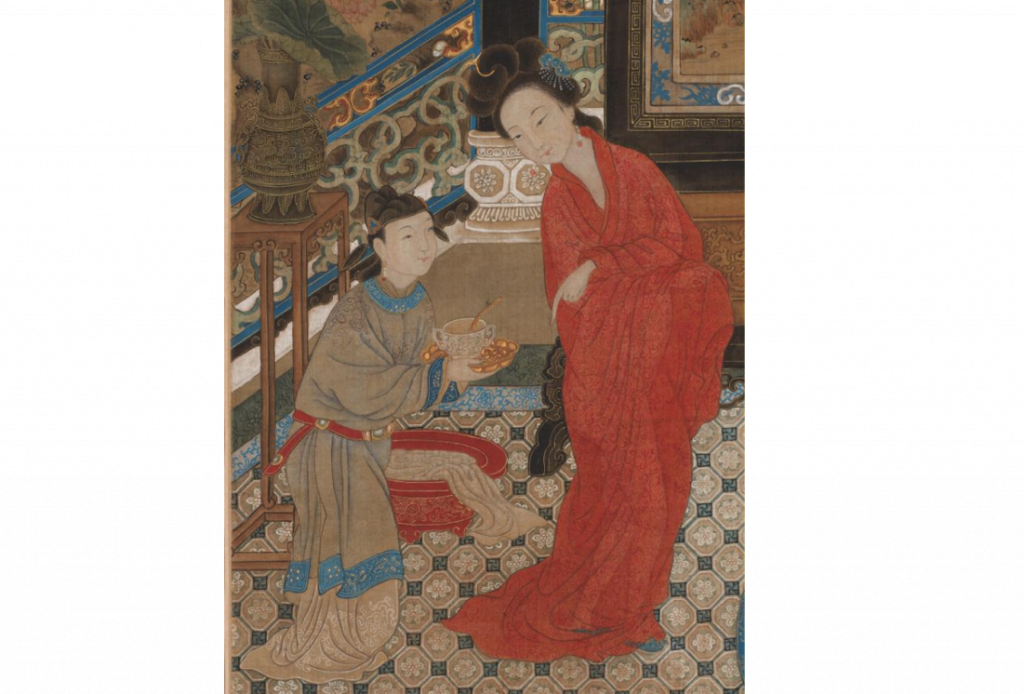

Stories of Yangdi’s well-known “pleasure tour” through the lower Yangzi delta are still told by Chinese storytellers in China today and had become the subject of racy vernacular romances by the 17th century. Legend suggests that Yangdi even had the custom of being drawn through the streets in a carriage pulled by unclad young men and women who would unceremoniously topple upon each other when the ruler pulled back on the reins.

Losing the support of the gentry landholders, the Sui economy eventually foundered, and uprisings began. Retreating to the south, Yangdi was eventually assassinated in 618 CE at the hands of his most trusted general’s son and the empire was dissolved. In the meantime, however, a capable general named Li Yuan and his brilliant, but ruthless son, Li Shimin had managed to position themselves for conquest and the rule of their own dynasty—the Tang.

Tang Dynasty (618-906 CE)

Chinese historians regard the Tang dynasty as both a revival of the best of the Han dynasty and as the high point of power and culture in Chinese history. An open, cosmopolitan era, the Tang was a time when cultural influences and ideas streamed into China along the Silk Road, and China became a model for emerging kingdoms in Korea and Japan. Its capital, Chang’an at times had a million inhabitants and drew peoples of many faiths and ethnicities from all over Asia and perhaps beyond. Art and literature also famously flourished in the Tang period, which is seen as the peak moment of Chinese lyric poetry.

Li Yuan, the founder of the dynasty, was a military leader of possible Toba background. Allied for a period with threatening Turkish nomads, he and his son Li Shimin toppled the weak Sui government and ruthlessly took control. In the process, Li Shimin killed his elder brothers (who were conspiring against him), as well as many other rivals. Once assuming control, Li Shimin, also known as Taizong, went on to become one of the most effective emperors in Chinese history, leading a strong, stable, and influential state.

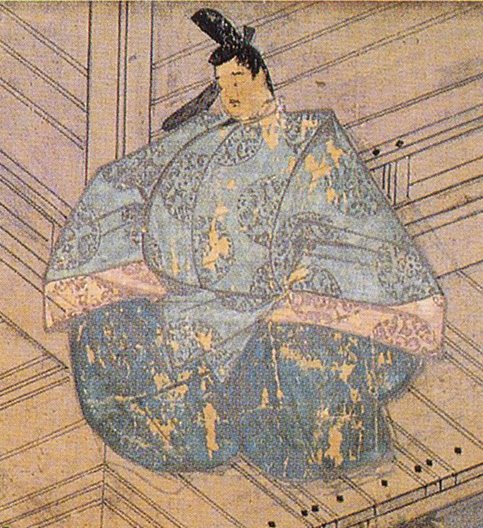

|

|

The civil and military bureaucracies were revived and expanded under the Tang. Below the emperor were civil officials and military leaders, largely drawn from the powerful gentry, families with large hereditary land holdings. Middle-level positions were filled by men from provincial gentry families and those who did well in the civil service examinations that were reinstituted in the Tang. The greater populace was comprised of farmers, artisans, craftspeople, and traders. Large armies were deployed on the northern borders and local armies and militias were filled with peasant farmers.

Military campaigns were carried out against Turks in the northwest and eventually against Korean states in the east, with the Tang forming a special relationship with the kingdom of Silla. Chinese influence on Japan (in the Nara and Heian periods) was also great at this time. On other fronts, in the 7th century the Tibetan state became very powerful to the west, and, in what is now southwest China and parts of Southeast Asia, a large kingdom called Nanzhao arose.

Land was an issue from the very beginning in the Tang. Among the first acts of the new rulers were attempts at land reform. In an attempt to weaken the holdings of powerful gentry landholders, land was re-divided, giving farmers equal shares of land—a system that had been tried in earlier times, including Wang Mang’s experiments in the Han and also for a while in the Toba kingdom. This “equal field” system offered both advantages (land to till) and disadvantages (taxes and corvée labor) to the peasants. Over time, many moved to the less restricted south, eroding the tax base. Another old system called baojia (collective households) was also tried. In this system, the farm folk were divided into five-family groups who were responsible for collectively submitting their taxes and annual labor quotas for state projects. Even this proved ineffective, and the attempts at land reform gradually diminished as the gentry regained power over more and more land.

Several colorful rulers and other palace figures populate Tang history. Among these is Empress Wu Zetian, arguably the most powerful woman in Chinese history. She came to the imperial court as a concubine of Li Shimin, but later had a relationship with his son, Emperor Gaozong. She eventually became his empress after forcing him to divorce his wife and succeeded in placing her son on the throne. She later deposed him and placed herself in power as emperor of her own Zhou Dynasty, which lasted from 690-701 CE. According to Wolfram Eberhard, this was in part possible because women in the Tang had more freedom of movement than in earlier and in later times due to lingering attitudes from the nomad kingdoms in the period of disunity. Once in control, Wu Zetian, in an attempt to consolidate her power, moved the capital east to Luoyang and away from the powerful gentry families of Chang’an. She instituted reforms in the examination system and government that made it more difficult to succeed solely on family connections and women were allowed to take civil service examinations to become officers in the court. She also promoted the interests of her allies, the Buddhists. Many monasteries became very rich during her reign. Huge temples and a massive iron pagoda were built with government support. Wu Zetian was a good administrator and the country was strong under her rule, though under constant threat from the Turks. Nevertheless, historians have been unkind to Empress Wu, traditionally describing her as evil and debauched. In recent years, her accomplishments have begun to be better appreciated.

|

|

Empress Wu was eventually forced from power and the Tang was restored. Soon after, Emperor Xuanzong came to power. He was a capable ruler who fortified China’s northern borders by the establishment of nine military command zones staffed by his appointees. He also made reforms to government administration and finances and attempted to deal with problems of grain transport and taxation of the peasants. In his later years, however, he became infatuated with a young concubine, Yang Guifei. Their love affair is one of the most popular tragic love stories in China. During this period, one of the border commanders, a man of mixed nomad stock named An Lushan ingratiated himself with Yang Guifei. He later fomented a rebellion that ended in 763 and marks the beginning of the decline of Tang power. Although the Tang was still in many ways a well-run state after the An Lushan rebellion, a crisis in leadership ensued. The borders also weakened, as did the imperial treasury, and rebellions ensued. Eventually smaller military states began to appear in northern China. Eventually Tang fell apart, ending a great period of openness, creativity, and power.

|

|

Second Period of Disunion (906-960 CE)

The decades after the fall of the Tang dynasty are known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms, referring to a succession of small states that came and went during this short period of time. It was a time of division between north and south and of rapidly changing administrations. By 960 CE, China was again reunited in the Song dynasty.

PART 6: SHIFT TOWARDS “MODERN TIMES”

Song Dynasty (960- 1279 CE)

The Song marked a period of transition toward early modern forms of society as many of the powerful gentry families of the Tang period crumbled and a new era of social mobility for males of all classes commenced. The new leaders brought the military under control and strengthened the civil side of the government with modifications in the civil service examinations. As J.A.G. Roberts has noted, the society was becoming more meritocratic, with less emphasis on family background.

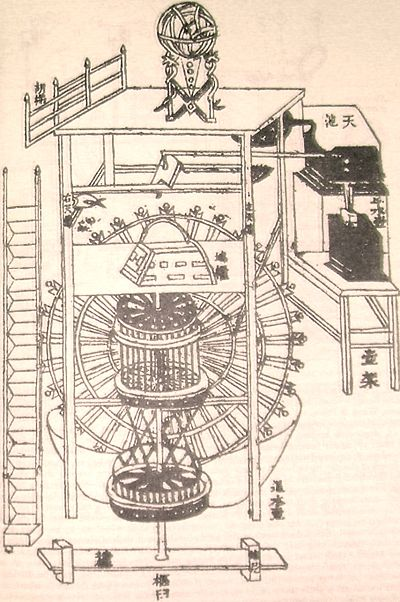

As described in Chapter 2, the development of new styles of urban life was associated with a growing middle class. This growth was due in large part to an increasingly sophisticated economic system that allowed for the expansion of merchant guilds and revived the use of money (which had declined in the previous eras). In part, this development was due to a shift in geographical focus southwards to the Yangzi delta, an area that had been growing in population for centuries and had been made more accessible due to the canal links to the north. The delta cities of Hangzhou, Suzhou, and Yangzhou all became important economic and cultural centers, and today offer some of the finest examples of Chinese garden architecture in existence. Scholars in these cities advanced the arts of landscape painting and poetry during this period. Many technological advances also occurred during the Song, including the widespread introduction of printing, development of advanced military devices employing gunpowder, improved irrigation techniques, watermills, large mechanical clock towers, and so forth.

One less “modern” change was an increased restriction of the lives and activities of women both within and without the home. During this period, for instance, discourse that discouraged widows from remarrying was elaborated and grew more popular. Although many women in this period were engaged in household textile production, they were seldom allowed to leave the home except for occasional visits to temples or to attend certain festivals. The relative freedoms of the Period of Disunion and the Tang were replaced by a stricter system of clan and household management that gave more power to males, especially male heads of households. Neo-Confucianism, which saw further developments in the Song, played a part in defining this increasingly constricting vision of women’s roles in society.

Although in many ways developments in the Song set new directions for the development of urban, mercantile lifestyles that continued in some cases into the early 20th century, the era on the whole was militarily weak and the dynasty was subject to invasion. Indeed, the Song is divided into two parts—the Northern Song (960-1127 CE) and Southern Song (1127-1279 CE)—due to foreign invasion. By 1115 CE the Jurched, a people from the northeast, had conquered the lands north of the Yangzi River, setting up a large state called Jin. A Tibetan-related group known as the Tanguts established another state, called Xixia in the northwest in present-day Ningxia. In the southwest, a successor to the Nanzhao kingdom still held sway. As a result of the Jin invasion, the Northern Song capital, located in the city of Kaifeng, moved to the southern city of Hangzhou. For a time, the population of Hangzhou numbered over one million inhabitants. Although the Song continued in the south for over a hundred years, it too eventually fell in 1271, this time to the Mongols, who, under the leadership of Genghis Khan, had ravaged the kingdoms to the north, including the Jin.

Mongol Interlude (1271-1368 CE)

An overview of the Mongol era in East Asia is included in the Timeline. After the Mongol destruction of the Jin and Xixia states—which included the slaughter of an estimated 90 percent of those populations—the Southern Song fell to the Mongols in 1271 CE (although the conquest was not actually completed until 1279). The Mongols had superior military organization and a better grasp of the advances in military technology such as siege engines, primitive rockets, and simple cannons than had previous northern invaders, and for the first time China fell completely under foreign rule. As Wolfram Eberhard has noted, for the next 631 years, China would be under the control of foreign invaders for 355 years and under Chinese rule for only 276.

Khublai Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan, had spear-headed the defeat of the Southern Song and founded a dynasty in China known as Yuan, declaring himself emperor. In order to keep the realm under control, he instituted a system of ethnic stratification that put Mongols of various origins at the top of the hierarchy, other northern peoples such as the Uygurs and the surviving Tangut were in second place, while northern Chinese (who had a long history of interaction with the steppe people) were in the third position of trust. The southern Chinese were at the bottom. Many government and clerical positions were staffed with people from the northwest and Central Asia—especially Uygurs from the now Islamic areas of Xinjiang— who learned both Chinese and Mongolian. Most Chinese, especially in the rich Yangzi river valley were shut out of governmental appointments. Some scholars, like Guan Hanqing, released their creative energies by writing dramas, an art form that appealed to both the Chinese and their Mongol overlords.

As the Yuan dynasty progressed, the economy weakened as large amounts of wealth left China in the hands of foreign merchants who were allowed many advantages over their Chinese counterparts. Pressure was also put on peasants by Chinese gentry who had been allowed to keep their lands and by Mongols who were given tracts of land as part of the spoils of war. The government also required tax revenues and corvee labor for massive public works projects, such as the overhaul of the old canal system, which was now needed to transport rice from the fertile south to the more barren north. A huge new capital, known today as Beijing, was built in the north. However, even Beijing was too hot for the Mongol rulers, and a special summer palace (in Tibetan style) was built still farther north in Chengde, near the old Mongol homelands. As the economic system weakened and some Mongols became disenchanted with a sedentary lifestyle, popular discontent grew. After about eighty years, ruling China became increasingly difficult. The Mongols were finally driven out by a peasant rebel named Zhu Yuanzhang, who had found common cause with the patriotic Chinese gentry. Zhu would become emperor of the Ming dynasty—the last Han Chinese dynasty in imperial history.

Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE)

As noted, the Ming (“bright”) dynasty was the last imperial dynasty ruled by Han Chinese. Once Zhu Yuanzhang (also known by the reign name Hongwu) ousted the main Mongol forces, he declared himself emperor. He moved quickly to gain military control of the whole country, in many ways following Yuan styles of military and government organization. It was not until 1390, however, that the final Mongol holdouts were driven from southwest China. Occasional Mongol raids still perplexed the Ming even in the 16th century.

In order to restaff and reinvigorate the government bureaucracy, Zhu revived the civil service examinations and set up government-sponsored schools throughout the land that helped examinees ground themselves in the Confucian Classics. He also experimented with new tax policies by introducing a system in which local gentry were responsible for tax-collection in their areas; and organized farm households into groups of ten, who then shared mutual responsibility for taxes and labor for public works projects.

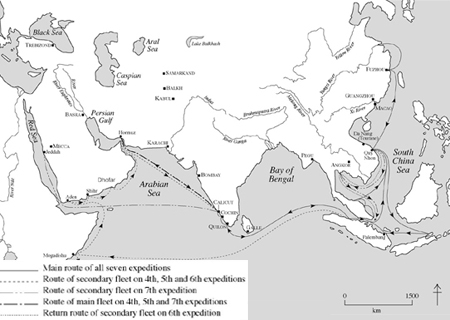

Zhu Yuanzhong’s grandson, the Yongle Emperor, moved the capital from Nanjing, in the south, to the site of the former Mongol capital, Beijing. Here, between 1402 and 1421, he built the massive Forbidden City, which still stands today beside Tiananmen Square. Yongle also led several military expeditions into the remaining Mongol realms as a deterrent show of force. Besides refurbishing the Grand Canal system to improve grain transport he commissioned the Moslem eunuch Zheng He on seven voyages across the Indian Ocean to the east coast of Africa and ports in the Arabian Sea. One detachment of his men made a pilgrimage to Mecca and recent genetic research has confirmed legends which say that some of his sailors remained behind and lived in communities in Eastern Africa. The massive fleets of over 300 ships, including several huge treasure boats ten times the size of the Santa Maria (a ship in which Christopher Columbus “discovered” the “New World” in 1492), must have inspired awe and respect in all who encountered them. Yet, for some reason Yongle lost trust in the enterprise (and in Zheng He). He ordered the fleets burned and China lost its initiative as a commercial, sea-faring power. Years later in the dynasty, Japanese pirates would constantly raid the Chinese coast.

|

|

|

Zheng He’s voyages and their legacy: (Left) A comparison of the size of Zheng He’s ship to that of ship of Christopher Columbus. (Center) A Map of Zheng He’s seven voyages. (Right) Dr. Mwamaka Sharifu of Lamu Island, Kenya, who may be a descendant of Zheng He’s crew. In 2005 she received a full scholarship from Nanjing University to study traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and recently graduated, taking all her coursework in Chinese. |

||

Other events also marked a shift inward. The Mongols again proved a threat, actually capturing the reigning Ming emperor around 1448. The eventual result was a revamping of the Great Wall, which was initially formed from several existing walls and rebuilt and fortified along the borders of the northern steppe. Due to relatively stable times and advances in agricultural techniques, the Chinese population reached 150 million by 1600. New strains of hardier and faster-growing rice were developed and new crops such as the white potato, sweet potato, maize, peanuts, hot peppers, and tobacco were arriving from the New World via the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and other Europeans who were now taking control of the world’s sea routes.

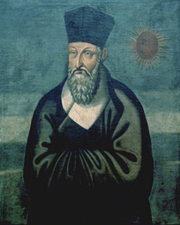

Portuguese Jesuit priests, representatives of a highly learned sect of the Catholic Church, were the first sea-faring Europeans to arrive in China during the Ming, making contact in 1514. By 1582, the famous Jesuit Matteo Ricci, like Marco Polo in the Yuan dynasty, had learned Chinese and even wore Chinese clothing. Chinese intellectuals shared their knowledge of astronomy and their inventions with the Jesuits, who in turn introduced aspects of European mathematics and science of the day. During the Ming, printing became even more widespread than in the past and a wide variety of books, including vernacular short stories and romances, found ready markets in urban areas.

Eventually the combination of a decline of leadership that was coupled with corrupt eunuchs at the imperial court, destabilization of the economy due to an influx of foreign silver, population growth, abusive tax policies, and popular rebellion weakened the Ming. Among the rebels fighting to overthrow the Ming was one Li Zicheng, who in 1644 managed to capture the father of a Chinese commander named Wu Sangui. Instead of submitting to Li Zicheng, Wu allied himself with Dorgon, a leader of the Manchus. The Manchus were descendants of the old Jurched peoples who lived in the rich forests of Manchuria (what is now northeast China and part of North Korea). For several generations, under able leaders like Nurhaci (1559-1626), the Manchus had been scheming to invade China. After Wu Sangui aided the Manchu forces in breaching the Great Wall they entered and soon took command of all China.

PART 7: FROM 1644 CE – PRESENT

In 1644 CE the Manchus established the Qing dynasty. It lasted over two hundred and fifty years, far longer than the Mongol occupation. The Manchu empire extended China’s borders to their greatest extent in history, bringing allies such as Tibet and the northwest regions of Xinjiang under direct Chinese rule. Incredibly strong in its earlier years, the dynasty declined by the early 19th century due to a combination of rapidly rising population, incompetent rulers, inner revolts, and outside forces that arrived by sea, rather than by the traditional land routes. In 1911-12 the dynasty collapsed, replaced by China’s first attempt at setting up a Western-inspired republican government.

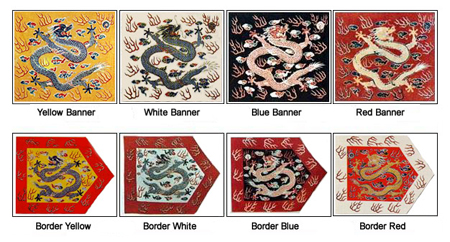

For generations before the takeover, Manchu leaders such as Nurhaci and Abadi studied Chinese culture and history in preparation for their invasion. Related to the populations of the ancient Jin state, the Manchu “banners,” as they called their military units (in Mongol tradition), were composed of Manchus, Mongols, mercenary Chinese, Koreans, and other ethnic groups. Once the Manchus took hold of power, they instituted a system that kept much of the Ming system of rule intact and allowed many Chinese to continue to serve in office. Eventually a dual administration system was developed, with both Chinese and Manchu filling complementary government positions (something like the dual nature of the Communist Party and People’s government today). In many cases, local order was kept by the Chinese gentry.

All imperial documents were written in both Chinese and Manchu, though as the years passed, Chinese became the de facto court language. Nevertheless, attempts were made to preserve Manchu culture. Immigration into the Manchu heartland was at first forbidden. Males in the new realm were required to shave the front of their heads and grow a long, plaited queue, new dress styles demanded that garments fasten from the side, and Manchu women were forbidden to adopt the Chinese fashion of foot-binding. This painful disfiguring practice involved winding long cloth strips tightly around girl’s and young women’s growing feet in order to shape them into small “golden lotuses.” Instead, upper class Manchu women wore high platform shoes and distinct, elaborate headdresses.

|

|

| Manchu women’s clothing and hair styles in the late Qing dynasty. | |

Two early Manchu emperors brought the Qing dynasty to its peak. These rulers were Kangxi and his grandson, Qianlong. Kangxi ruled for 55 years (1667-1722) during a time of great expansion. Qianlong left the throne after a reign of sixty years, a few years before his death. Under Qianlong the borders of China grew to their largest in history. Much of the expansion into lands on the northern and western borders seems to have been made to create buffers from perceived threats of overland invasion. Culturally, the Qing strongly censored historical and literary accounts for any anti-Manchu sentiments or romances, such as Outlaws of the Marsh, that might incite anti-government sentiment. On the other hand, Kangxi authorized the creation of a comprehensive dictionary of the Chinese language, encyclopedias of knowledge, and huge compendiums of ancient writings. European learning continued to be introduced into China, including Western methods of painting employing linear perspective. In the 18th and 19th centuries a number of great works of fiction were produced, as well as large numbers of plays. In all, the reigns of Kangxi and Qianlong were times of intense activity among the intellectual class, which included Han Chinese and the increasing number of Manchus raised in the traditions of Chinese scholar-officials.

By the late 18th century, however, there were signs of decline, signaled by an uprising in Shandong of the White Lotus Sect, a Buddhist-inspired underground organization that had been involved in previous rebellions. Abuses by local officials seem to have been the cause. As Qing leadership waned in the early 19th century, the population was also outgrowing the means to sustain itself, which also led to rebellions. Large numbers of people, especially in the newly settled southwest, were living on very marginal land. This was due in part to the earlier introduction of crops like sweet potatoes and tobacco that could be grown in poor soil.

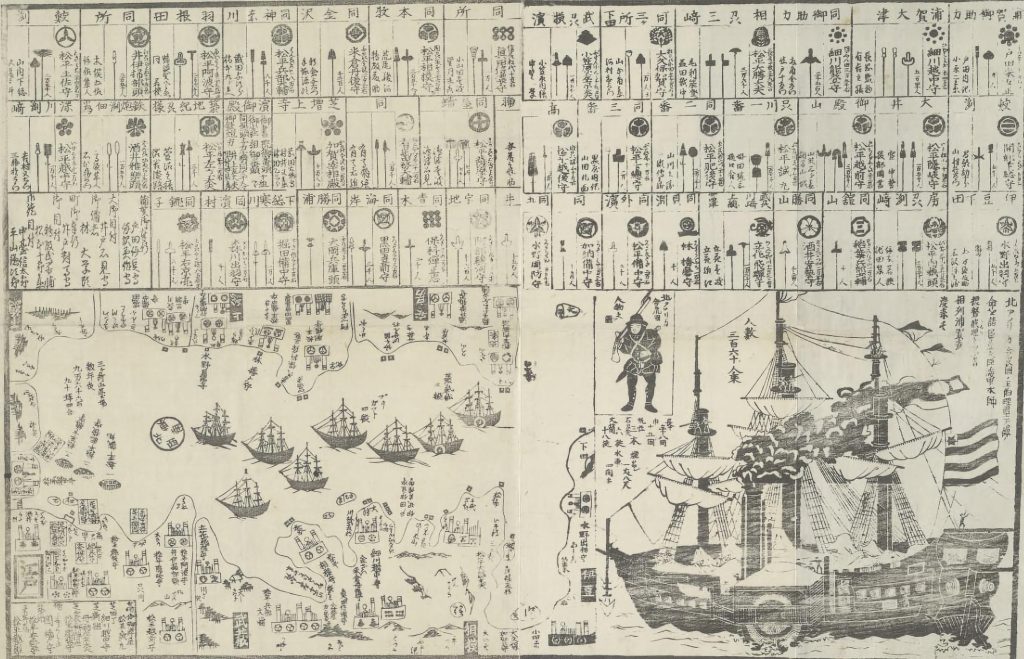

Trade frictions grew with the European powers, especially Britain. British merchants of the East India Company had long sought to right trade imbalances with China. The Chinese had little need for anything other than silver from the West, selling porcelain, silk, and tea in return. Eventually in order to recoup their silver, the British began illegally importing Indian opium into China, with the help of corrupt Chinese middlemen in specially designated coastal trade zones. When the Qing government moved to halt the illegal trade by burning confiscated opium, British traders petitioned their own government for redress. British gunboats fired on Chinese positions along the coast, outgunning the crude Qing cannon. The result of this so-called Opium War (1839-1842) was humiliation for the Qing government and a series of unequal treaties, including the Treaty of Nanjing that ceded the port of Hong Kong to the British in 1842.

While foreign influence began to grow on Chinese soil, internal pressures mounted, finally erupting in the devastating Taiping Rebellion which raged from the early 1850s until 1864 and leaving an estimated 30 million dead. The rebellion began in the southern province of Guangxi and was led by a visionary of Hakka ethnicity named Hong Xiuquan. After failing at the local civil service examinations, Hong studied with foreign Christian missionaries. He had a vision that pronounced him the younger brother of Jesus Christ, who had been sent to earth to create a kingdom of “great peace.” Disenchanted peasants of several southern ethnic groups pledged themselves to Hong’s cause, giving up their property (which was then fairly redistributed among the revolutionaries), as well as abstaining from opium, tobacco, alcoholic beverages, gambling, prostitution, polygamy, and foot binding. Men and women were declared equal in the movement and soldiers lived a communal lifestyle. It is interesting that the grandfathers of several of the later Communist revolutionaries of the early 20th century were Taiping rebels. As the movement grew in force it swept through southern China and nearly took the southern capital of Nanjing. The rebellion was weakened by contradictions among the Taiping leadership. Qing government forces, now partially Westernized in military hardware and tactics (though still behind those of Japan), finally put down the rebels with the help of European soldiers.

|

|

By the end of the 19th century it was becoming clear to many in China that serious changes must be made in order to preserve Chinese sovereignty in the face of aggressive European—and eventually Japanese—imperialists. Although a Qing “self-strengthening movement” had some success in military reform, the reforms were hindered by weak imperial leadership. By the end of 1890s the imperial throne was under the influence of a former concubine known as the Empress Dowager Cixi. In response to foreign naval threats, she squandered funds on a large marble pleasure boat, now a tourist attraction at the Summer Palace in Beijing. After losing the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 (fought over control of Korea), it became clear to all that Chinese power was little more than a shadow of the past. Reformers, including Kang Youwei, finally convinced the imperial government to institute experimental reforms in government and military in the spirit of the reforms that had all too clearly yielded results in the Meiji Reformation in Japan. The “One Hundred Days of Reform” (named for how long the reform lasted) were too much of a threat to the conservative imperial order, however, and its leaders were either beheaded or fled to Japan.

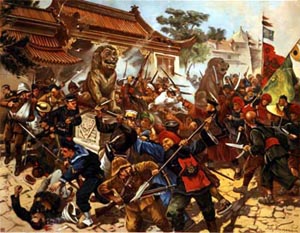

Things soon went from bad to worse. Another massive uprising, caused by famine and unstable social conditions, erupted in Shandong. This movement was led by the so-called Righteous Order of Harmonious Raised Fists (Boxers, for short). In 1898, the Boxers, who included de-mobilized soldiers, went on an anti-foreign rampage. A number of foreigners were killed, and armies of seven European countries and the United States fought off Boxer attacks throughout northern China. In the melee the imperial library was looted and huge amounts of treasure and antiquities were taken from China by foreigners, who ironically demanded indemnities for their own losses. More pressure was brought to bear on Chinese territory, and a fierce battle for territories in northeast China was fought between Russia and Japan, won by the Japanese, was fought in 1904-1905.

By 1905, the imperial system was in a state of near collapse and the civil service examinations were abolished in that year. Reform and revolutionary movements were rising both within and outside of China, many led by young Chinese students and others influenced by ideas they had learned in Japan and the West. Among these was Dr. Sun Yat-sen, who helped organize the revolutionaries that eventually ignited a rebellion in the city of Wuhan in the Yangzi Valley. Although Sun was outside China at the time, he soon returned and was elected president of the newly declared Republic of China. This was a modern style, Western-inspired government supported by a variety of social classes that all wished to see the Qing come to an end. Within a month, however, Sun stepped aside and Yuan Shikai, head of the Beijing military, was elected as president. The new government was unable to take control of the whole country, and local military governors began assembling their own spheres of influence. By 1915 Yuan Shikai declared himself emperor but died a few months later. Other leaders followed, but none could not stop the proliferation of warlords who set up local power bases, much as small states arose after the collapse of earlier Chinese dynasties. Sun Yat-sen founded an opposition government in southern China supported by his followers, the Nationalist Party.

By 1919, following ill-treatment of China under the Treaty of Versailles that ended WWI, a movement arose among students and intellectuals at the new Peking University in Beijing. The May Fourth Movement was an intellectual and spiritual revival among educated, urban Chinese already exposed to many Western ideas and technology. Protests and marches were held and some students were shot by government soldiers. The students called for reforms in government, science, and culture—all similar to modernizations made in Japan over fifty years before.

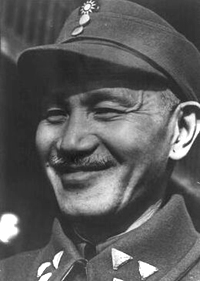

After the death of Sun Yat-sen in 1925, Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi), a young military officer who had received training in the Soviet Union, took control of the Nationalist Party. He quickly moved against the warlords. He undertook the Northern Expedition in 1927 and was quite successful in gaining control of parts of eastern China. His efforts were complicated, however, by the rise of the Chinese Communist Party, which was founded in 1921 by a handful of young revolutionaries inspired by the successful formation of the of the Soviet Union in 1917. Pushed underground by the Nationalists, the Communists retreated to mountain lairs in southern China, where they perfected their reform movement in neglected peasant areas.

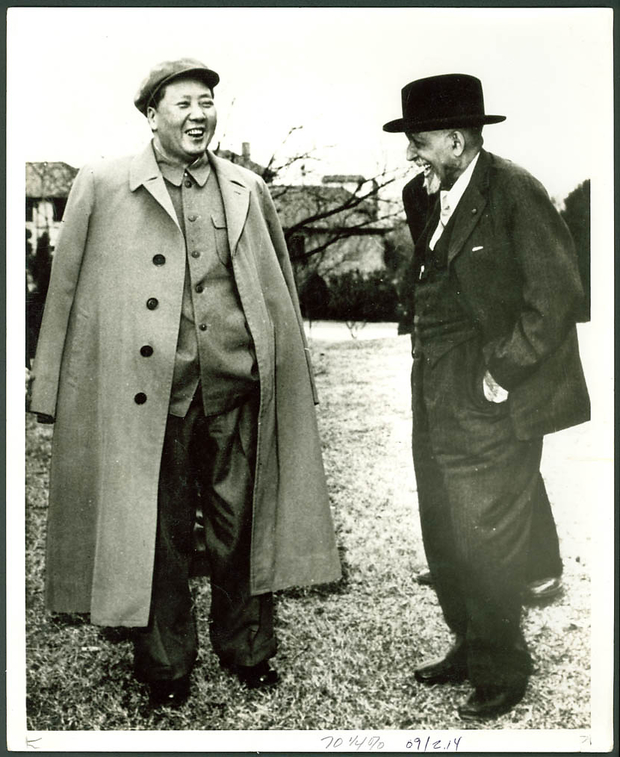

By the late 1920s, the Japanese were threatening northeast China, where they set up a puppet-state in old Manchuria. A prolonged movement by the Nationalists to liquidate the Communist strongholds led the beleaguered Communists to undertake a retreat, walking 5,000 miles through the extreme terrains of southwest and western China. The Long March took over a year, from 1934-1935, and only 20,000 of the original 100,000 participants survived the march. It ended in a place called Yan’an in the mountains of Shanxi province, not far from the ancient Qin capital of Xianyang (near modern Xi’an). Among the marchers were the eventual founders of the People’s Republic of China in 1949: Mao Zedong, Zhu De, Zhou Enlai, and Deng Xiaoping. For a time in 1936, there was talk of a united front of Nationalists and Communists against the Japanese. In the so-called the Xi’an Incident, Nationalist generals Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng, with the support of the Communist leader Zhou Enlai, kidnapped Chiang Kai-shek and forced him to join a united front with the Communists against the Japanese. This united effort, however, eventually fell through.

By 1937, the Japanese had invaded deep into China, bombing Shanghai and committing horrendous atrocities on the population of Nanjing. The Nationalist government, wracked by corruption and lacking in resolve, lost many troops in battles trying to protect the coastal cities. The government eventually retreated inland up the Yangzi River, finally creating a base in Chongqing, an area now within the borders of Sichuan province. Meanwhile, the Communists, from their base in Yan’an, spread their influence among peasants across northern China and penetrated behind Japanese lines using sophisticated guerilla warfare tactics.

As the Anti-Japanese War (1936-1945)—what the Chinese call World War II —was winding down, the United States, which supported the Nationalist cause, briefly entertained the idea of a coalition government between Communists and Nationalists, and even sent a mission to Yan’an in 1944. Once the war was over in 1945, however, the US aided the Nationalists by helping them move troops to northeast China to accept the Japanese surrender and to check the advancing Russians who were interested in regaining ports and railway lines in Manchuria. Eventually, however, despite US support of the Nationalists, the Communist following was strong enough—due in no small part to the common cause they had found with the peasants in resisting Japanese invasion—that they won the civil war. The Chinese communists drove Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalists to the island of Taiwan, which had been under Japanese control for over eighty years. In October 1949, Mao Zedong stood on the terrace in front of the Forbidden City in Beijing and declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

The early years of the People’s Republic saw land reforms and steps toward feeding, housing, and providing medical care to an estimated 400 million people in a country ravaged by over a century of almost constant war and rebellion. Mao Zedong, the major thinker behind the Communist revolution, was made Chairman of the Communist Party. By the late 1950s, questions began to arise among intellectuals and common people alike over certain of Mao’s policies, which were also challenged by some other Party leaders. In 1957, the government asked for constructive criticisms on its policies in a political movement known as the Hundred Flowers Campaign. The criticisms were more than Mao had gambled on and he soon launched a counter-revolutionary movement called the Anti-Rightist campaign. This resulted in the stigmatizing or imprisonment of many intellectuals and students who had offered even the most innocent suggestions.

This began a prolonged era of periodic, government-induced political movements that wracked and divided Chinese society well into the late 1970s, with occasional policy repercussions even into the 1980s.

|

|

In 1958, in response to inner-party criticisms of the Anti-Rightist campaign, which some moderate Communists thought had gone too far, Mao launched a movement called the Great Leap Forward. During this period, Mao cut off relations with the Soviet Union, which had been supplying technical support to China since 1949. Throughout the country over 700,000 People’s Communes were created in a further expansion of land reforms already instituted in the early 1950s. Communal housing and kitchens were set up all over the country. At one point, the populace was burdened with the task of melting down any metal objects they could lay their hands on in homemade smelters to raise China’s steel production to the level of Britain’s within five years, a challenge set by the top leadership. China could not rapidly overtake developed countries on a wave of Socialist zeal alone, however, and this utopian project failed. With the mass of peasants involved in steel production, however, harvests failed around the country and by 1961 over 30 million people (even according to Chinese statistics) had starved, a tragedy compounded by the actions of many local officials who, in trying to please their superiors, had inflated grain production figures reported to the central government.

By 1963, Mao had been skillfully shunted aside by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, leaders who suggested that experiments with basic market-based production be tried. Within a few years, however, Mao had rallied his many allies, and began a movement that indoctrinated the young people of China, urging them on as the vanguard of a radical new movement against counter-revolutionaries in the schools and government offices. This was the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

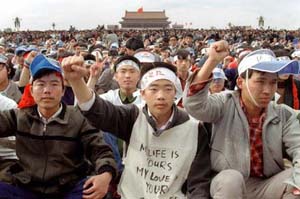

By 1966, huge rallies of young people, called Red Guards, were trekking (sometimes over a thousand miles) or riding free trains to massive rallies in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in hopes of glimpsing Chairman Mao as he spoke to them. Violence broke out as Red Guard groups “struggled” against “reactionary” teachers and officials. Some were beaten to death by overzealous students or committed suicide out of shame after public rallies in which degrading signs were hung around their necks and pointed dunce caps placed on their heads.

By 1968, the Red Guard movement had spun further out of control and factions fought among themselves to prove their loyalty to Mao. Eventually the Red Army interceded, and large numbers of students and urban youths were sent to rural areas to “learn from the peasants.” Life on the communes was not easy for many of the city youths and older intellectuals who had been branded as “counter-revolutionaries.” The peasants, with no clear idea of what was going on in the cities, often resented the sudden arrival of groups of city-raised youth.

By the early 1970s as Mao aged, a group called the “gang of four,” which included one of Mao’s wives, an actress named Jiang Qing, took control of the country. Also, during the early 1970s, US President Richard Nixon and his aide, Henry Kissinger, began secret talks with the PRC leadership. These talks eventually led to a well-publicized ping-pong match between Chinese and American athletes touted as “Ping Pong Diplomacy.” And, in 1972, Nixon visited China, meeting with Premier Zhou Enlai (a respected diplomat who had managed to stay the course through years of chaos), and a then-senile Chairman Mao.

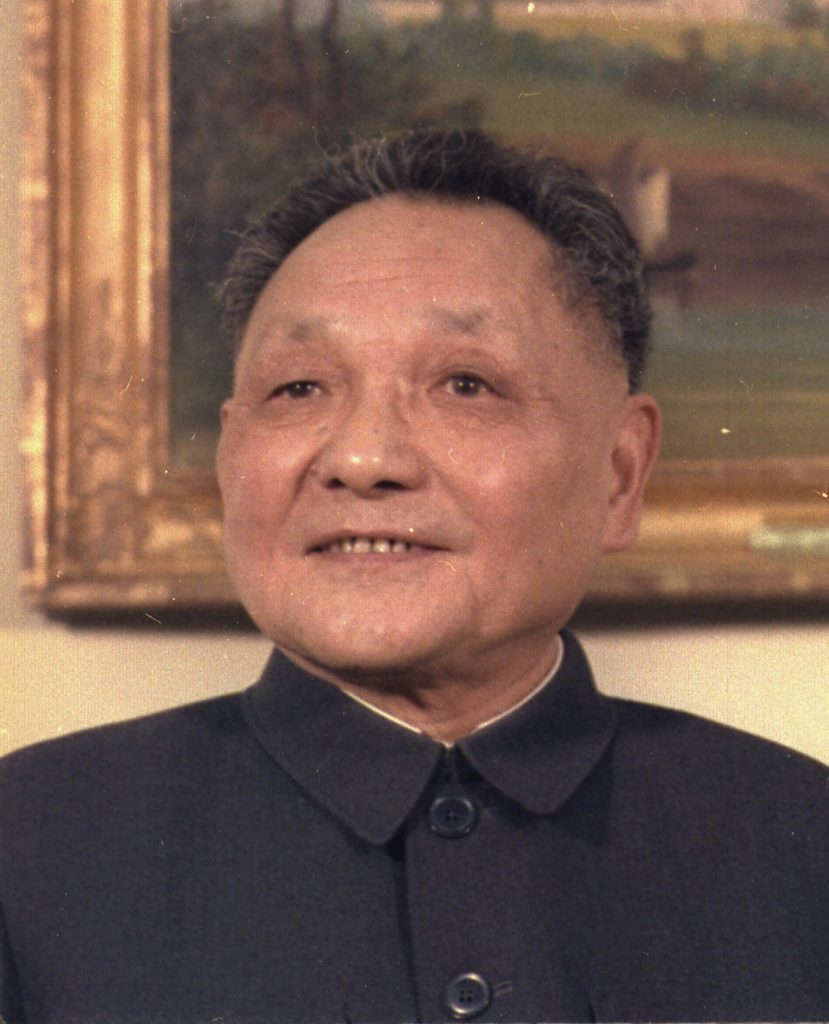

Mao died in 1976, a year that also brought the deaths of Zhou Enlai and Zhu De, and an earthquake in Tangshan that killed 250,000 people. The ten years of Cultural Revolution ended with the capture of the “gang of four” by the Chinese army. By 1980, reformer Deng Xiaoping (who stood only 4’9”) used his political skills to come to power. Jailed three times by Mao, he was always considered a creative intellect, due in part to several years spent in France in his youth. By the early 1980s, Deng had systematically set China on a new course towards a more open, economically viable society. Abandoning radical Maoist ideas on communal economy, the new plan was to create “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Although finding a new direction was sometimes difficult, in all the process was carried out in a very systematic way, combining socialist and previously taboo capitalist principles.