11 Module 10: Technology and Ecology

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

OUTLINE

A HISTORY OF INNOVATION

Many basic technological and scientific innovations that we take for granted today originated in East Asia or were influenced by developments there. Scholars like Joseph Needham have undertaken an extensive study of East Asian, particularly Chinese, contributions in the fields of technology and science, bringing renewed attention to a vast realm of innovations spanning thousands of years. Many of these innovations intersect in many ways with the arts, literature, and philosophy, as exemplified throughout this book. As noted in Module 1, early technological innovations in this region included silk production, wet-rice agriculture, bronze casting, and ceramics. These technologies paralleled developments in early civilizations in the western reaches of Asia and scholars continue to decipher early patterns of technology transfer and influence. Along with development, however, are the costs of environmental impact. This chapter will review the history of innovation in East Asia, the impact on the environment of recent decades of growth, and offer several case studies on development and efforts at sustainability.

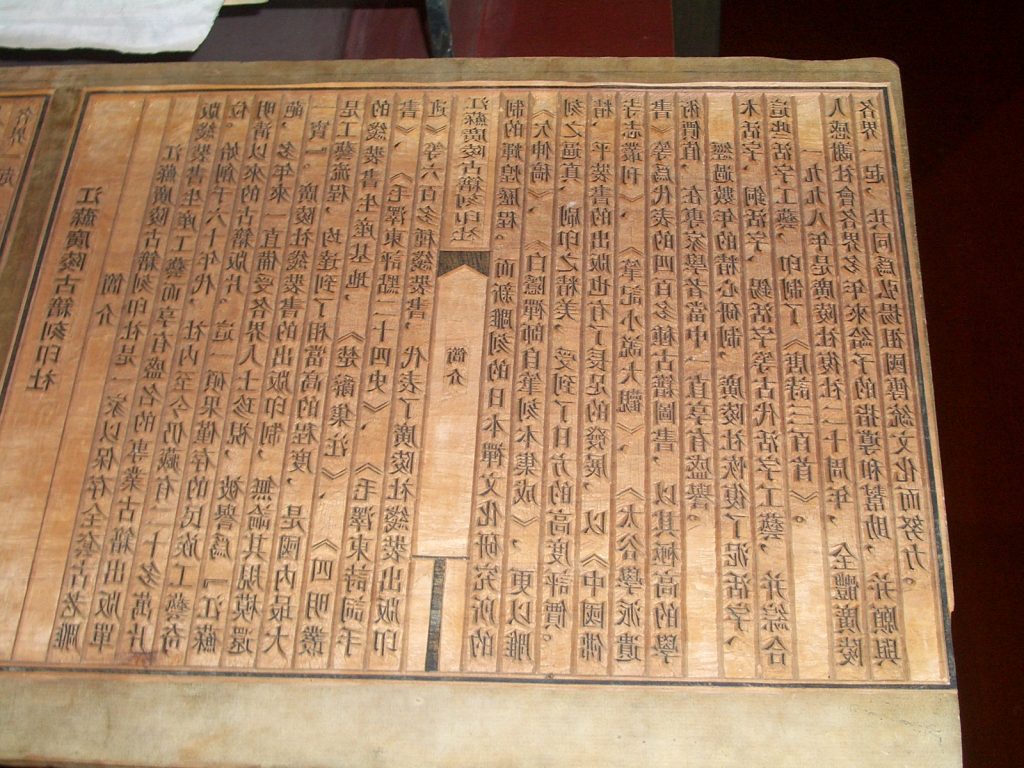

By the 14th century, with the increased opening of the overland trade routes brought about by the era of Mongol conquest, major innovations from China and other parts of East Asia made their way west to the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and Europe. These included the major Chinese inventions of gunpowder, the magnetic compass, paper making, and printing. The Korean invention of moveable cast metal type predated Gutenberg’s 15th century innovations in printing by several hundred years and there is evidence that the Koreans had wooden printing blocks at least as early as the 11th century. Although the times and routes of transmission are still under study, gunpowder (invented in China around the 9th century and used mostly for arrow cannons and martial fireworks during this era) and the magnetic compass aided European explorers and military powers in their later conquests and colonization of many other parts of the world. Gunpowder, or huoyao (“fire medicine”) in Chinese, was said to be invented accidentally by Daoist monks who were trying to produce elixirs to achieve longevity. Advances in Chinese sailing ship design and steering mechanisms may also have contributed to modifications in European ship designs.

-1024x644.jpg) |

|

|

|

In East Asia, paper making became an area of innovation in China, Korea, and Japan. Japan produced exquisite types of paper made from a wide variety of barks and plant fibers and the Japanese seem to have created a type of tissue that is the forerunner of today’s toilet paper. After the 16th century printing technology mushroomed throughout the region contributing to high literacy rates, a legacy reflected in the strong educational systems and emphasis on education that continue in East Asia today.

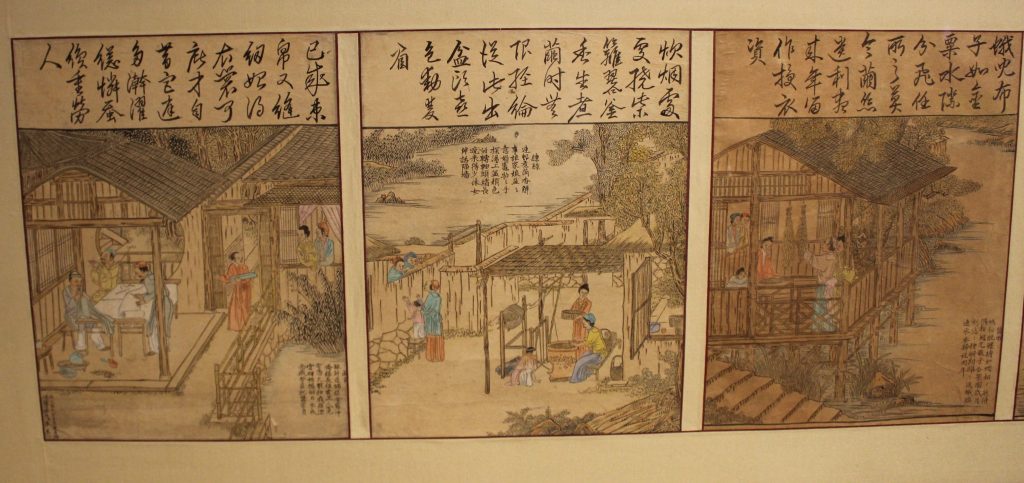

These 5 woodblock prints depict each of the major steps of the paper making process in ancient China. Similar processes were used in Korean and Japan.

- (1) Certain plants, especially the bark of mulberry or bamboo fibers, are gathered and broken down to be mixed with water, forming a slurry.

- (2) The fibers in the slurry are cooked then laid out in the sun to dry.

- (3) The dried fibers are pounded, then mixed in water again along with a gelatinous agent. Once thoroughly mixed, it was scooped onto a bamboo screen to form a thin sheet.

- (4) The paper is then stacked with felt between each sheet and pressed to squeeze out the excess water.

- (5) The sheets are brushed onto a flat wall to dry.

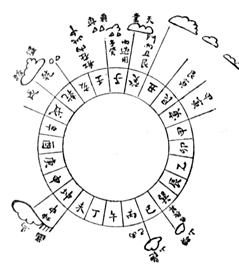

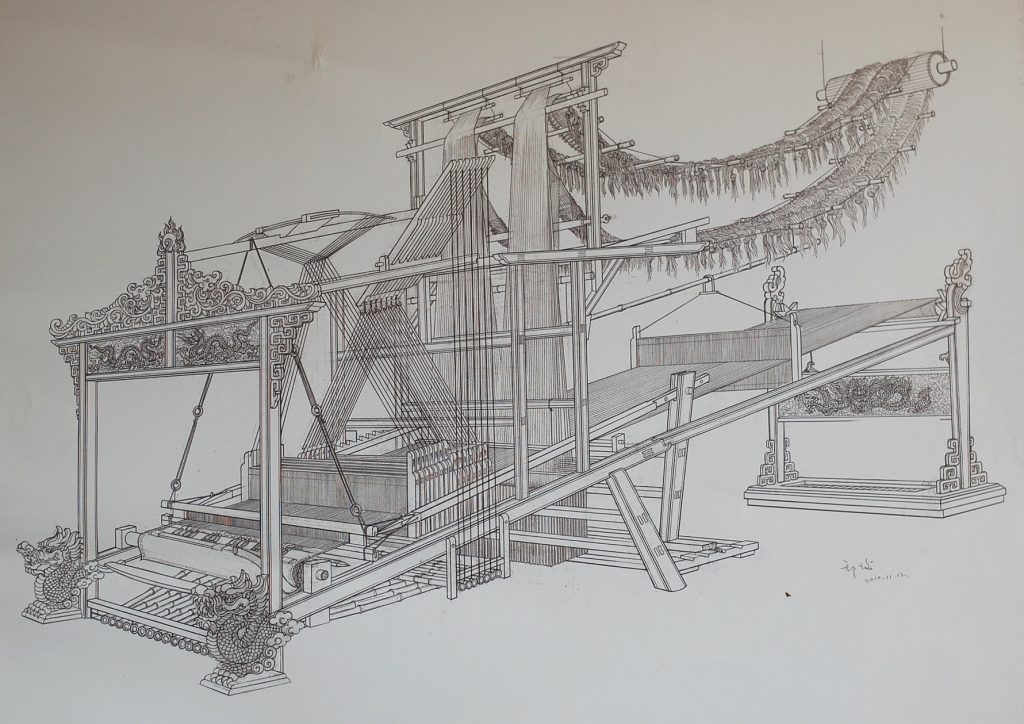

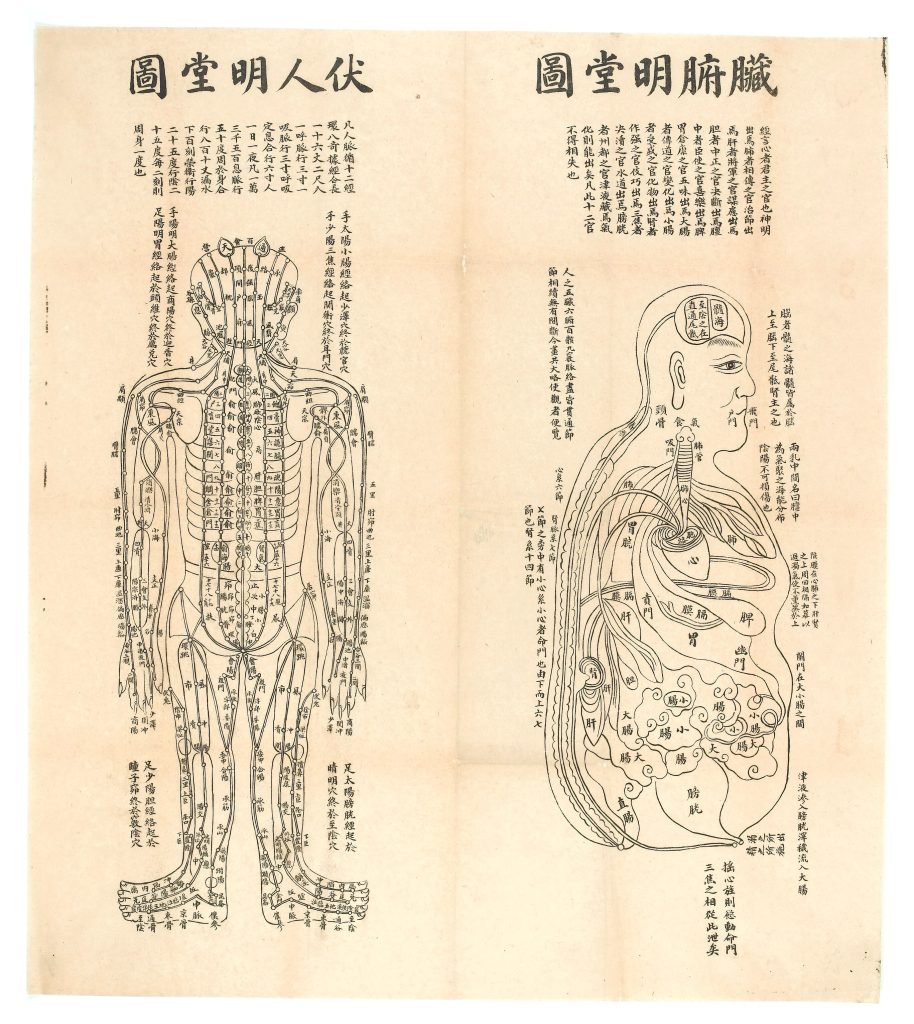

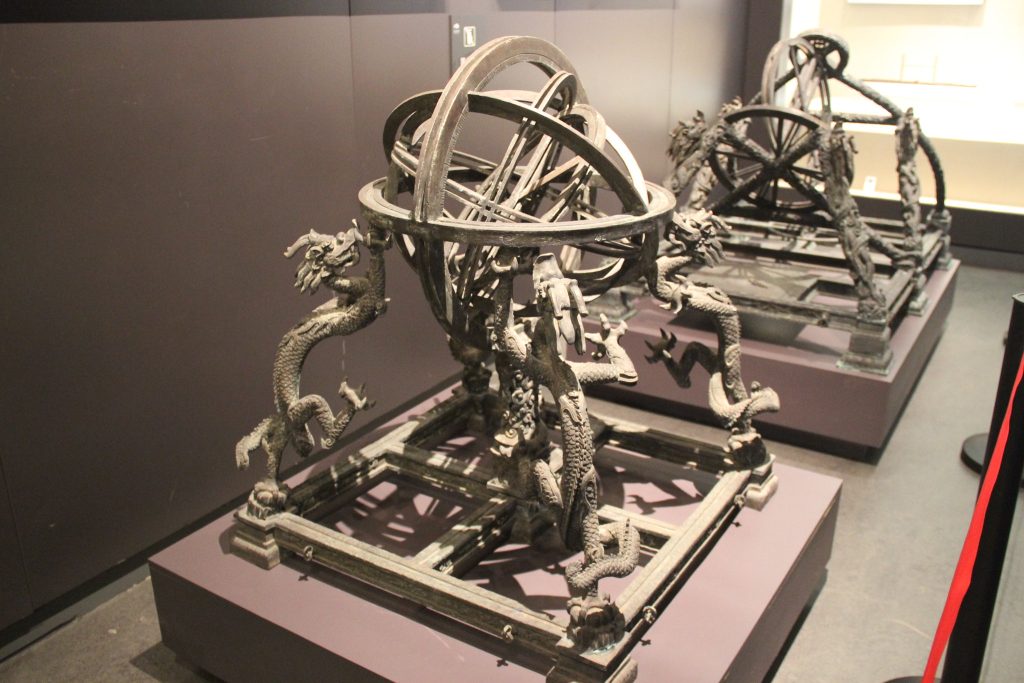

Other innovations included water-powered mills and water-moving machines; advanced looms and weaving devices; medical practices such as acupuncture which developed in China; the invention of astrological devices for charting the skies; a type of rain gauge to measure precipitation invented in Koreans, devices for detecting earthquakes. There were also discoveries in mathematics that in some instances pre-dated European solutions to these problems by centuries.

A drawing of a Yunjin brocade loom. This complex machine requires two people to operate, and with it they produced intricate woven patterns with thread made of such materials as silk, gold, and even peacock feathers. The clothing made from Yunjin brocade was traditionally worn by the imperial family in China or used in Buddhist temples. |

|

|

A sundial clock using shadows to count time. This is just one of several designs placed in areas throughout the Forbidden City in Beijing. |

Part of a series of four acupuncture diagrams by the Yuan dynasty physician Hua Shou (1304-1386), called “Mingtang tu” (Diagrams of the Illuminated Hall). For thousands of years, acupuncture has been considered a healing technique that taps into the internal channels through which the body’s qi flows. |

|

|

A reproduction of an earthquake detector invented in 132 CE by Chinese astronomer Zhang Heng. Historical records state that it operated as follows: when there was an earthquake happening in a certain direction, a ball would fall out from the dragon facing that direction into the mouth of a frog on the same side of the device. |

A reproduction of an astrological device called an armillary sphere, which was also invented by Zhang Heng. It shows the equator, horizon, the 2 poles, and so on. It was water-powered and could indicate the relationship between the earth and major stars in the sky. |

|

|

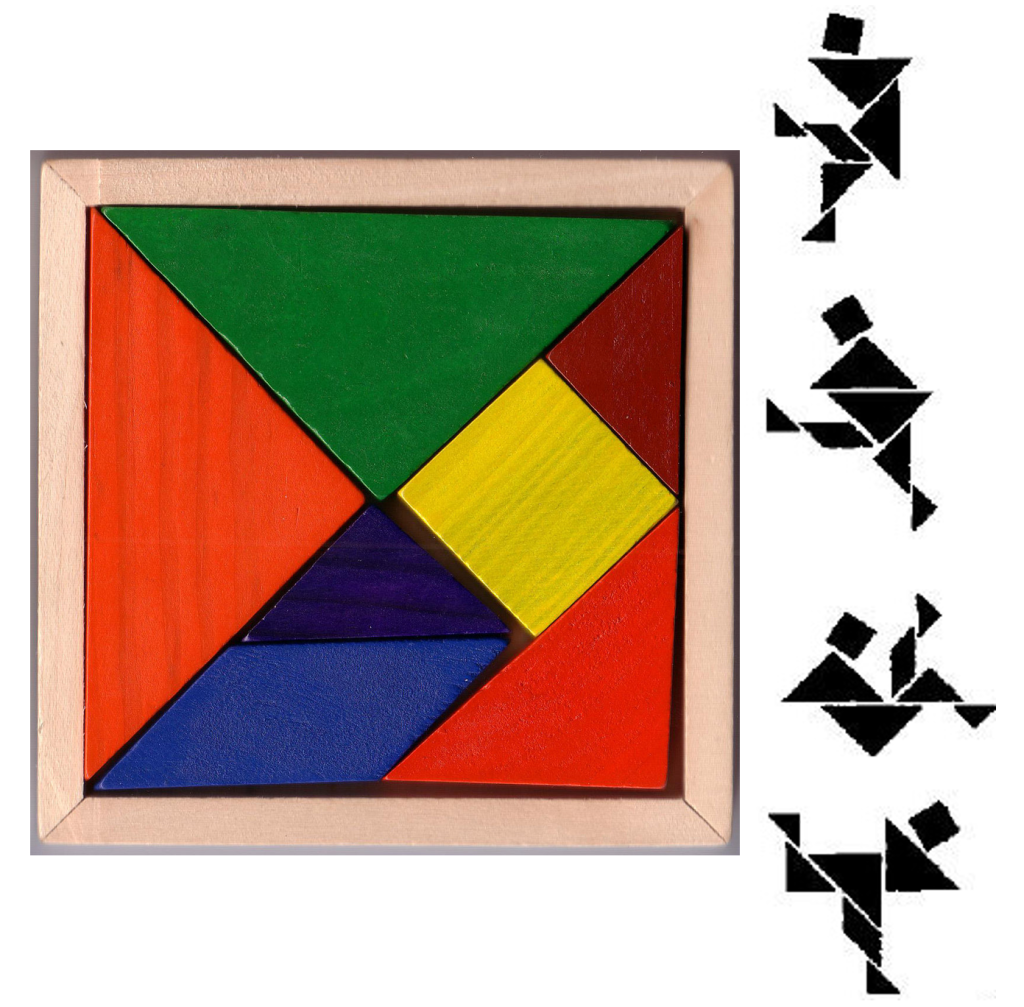

The tangram, or qiqiaoban in Chinese (literally “seven boards of cunning”), can be verified as far back as the 17th century, although they are often said to have been invented well before this. |

Early on, the Chinese developed technologies and procedures for carrying out massive public works projects that included the 5,000 mile Great Wall which snakes across northern China (actually a series of connecting walls made of different materials and of differing size and height); the Grand Canal system that connected north and south China by a complex system of natural waterways and human-made canals; and water control systems, such as the Dujiangyan irrigation project near Chengdu in Sichuan province. Started in 256 BCE by Li Bing and his son, this complex system of artificial shoals and walls altered the course of two rivers to prevent flooding and irrigate flat rice lands.

Korean innovations in astronomy and engineering are reflected in the Queen’s Observatory (7th century CE); sundials and water-clocks; and the complex interlocking granite chamber housing the magnificent Sokkuram Buddha near Kyongju. Many technological innovations including papermaking, bronze bell casting, and wooden architecture made their way to Japan via the Korean peninsula and from China via the Korean peninsula in the 6th to 7th centuries CE.

|

|

|

Japanese metalworking skill came to be highly regarded. Its craftspeople excelled at the production of superior steel swords, metal castings such as the great Buddha at Nara, and, in the late 15th century, the production of cannons and hand-held firearms influenced by Chinese and Portuguese designs.

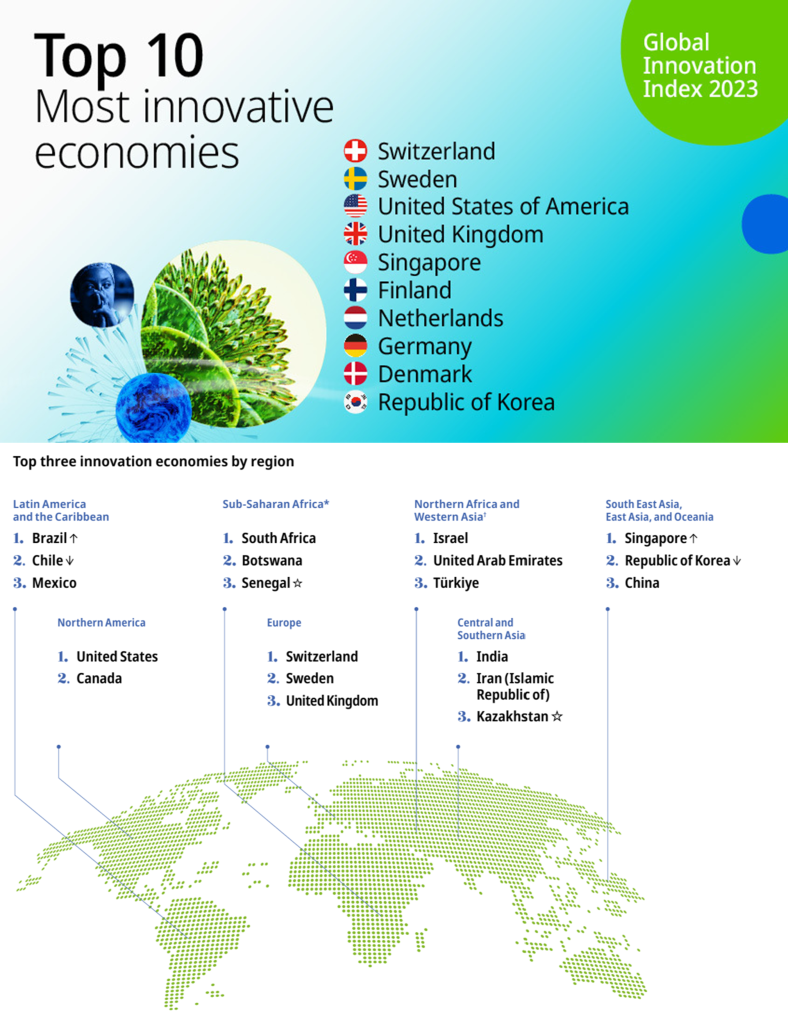

East Asia began to lose its edge in technology by the 18th century, however, at about the time when the European Industrial Revolution began. By the middle of the 19th century, Japan realized that the decline in East Asian technological innovation was putting the region at a geopolitical disadvantage. To counter this, Japan began importing Western methods of science and technology wholesale during the period of the Meiji Restoration. China and Korea later followed this trend over the ensuing decades. In post-WWII East Asia, Japan led the way in technological recovery, and in the decades since the 1950s, the entire region has again come into its own in the development and advancement of technology and science. These endeavors, of course, are now a global enterprise with many mutual benefits for nations worldwide.

A TRADITION THAT CONTINUES TODAY

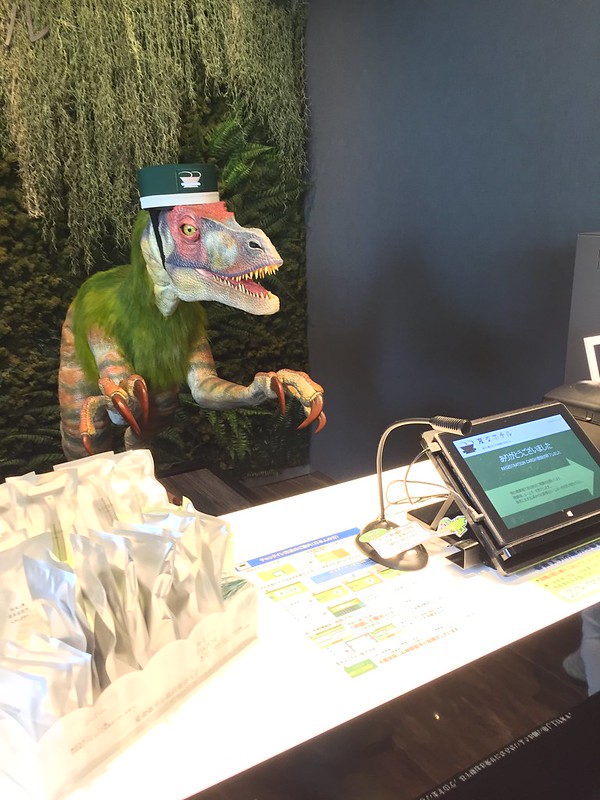

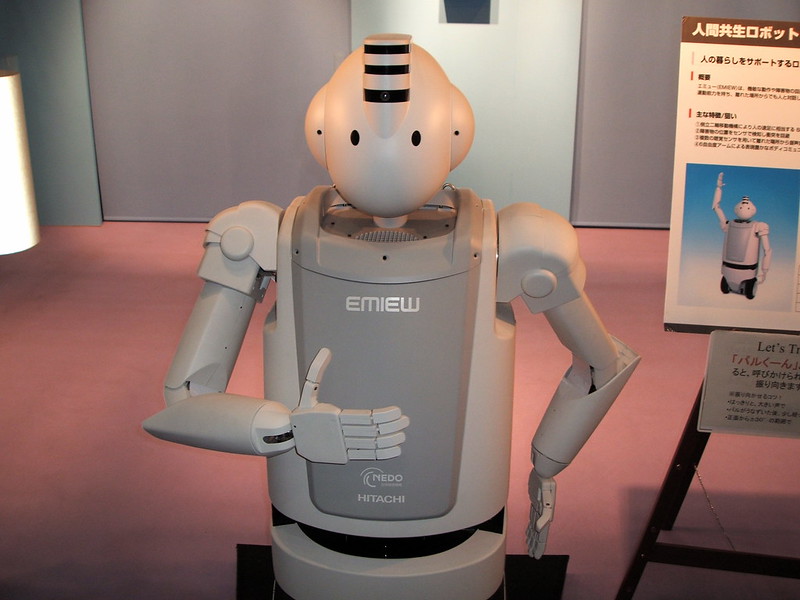

The effects East Asia cultures on the development of technology and on the human impact on the natural environment are ubiquitous in the modern world. Many Americans drive automobiles perfected in Japan and South Korea, with auto industries in both countries producing vehicles popular for their economy, quality, and fuel efficiency. Japan’s early entry into transistor research by the forerunner of SONY helped revolutionize popular culture, especially radio music, and lay the groundwork for the digital revolution of the 21st century. Whether it is the development of chip technology, fiber optics, ceramics engineering, satellite technology, magnetic train (magna-lev) track systems, ocean farming, agriscience, robotics, artificial intelligence, medical research on cloning, disease and pandemic control or the development of big data-based social monitoring systems, China, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan are deeply involved.

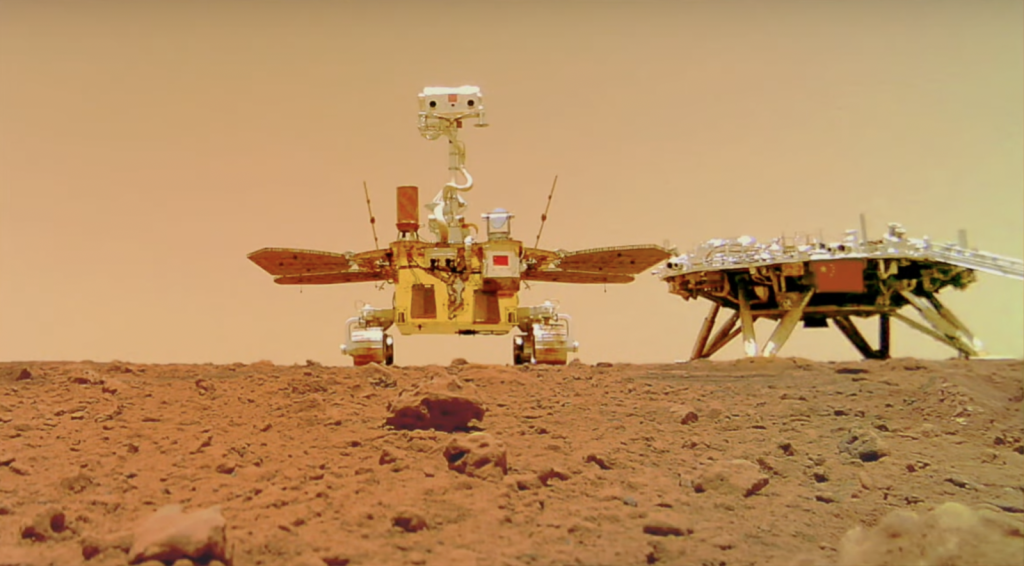

China’s burgeoning economy has also stimulated an aggressive space program, resulting in several successful manned space flights, followed by a lunar rover that landed on the dark side of the moon, and a successful rover landing on Mars in May 2021 (an event celebrated with a US NASA rover that landed on Mars just a few weeks earlier). The event was followed in June by the swift building and staffing of the new Tiangong (“Heavenly Palace”) space station, a project launched after China was shut out of the International Space Station a few years before. On earth, Chinese engineers and a large, well-trained workforce completed the largest single engineering project in history, the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangzi River ahead of schedule in 2009. In October, 2021, Kunming China hosted the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, with the catch phrase of creating a global “ecological civilization.”

Japan’s accomplishments in the industrial sphere include unsurpassed advances in the production of robots, with recent prototypes of human-like cyborgs nearly fulfilling the forecasts of decades of science fiction. South Korean firms have been especially innovative in HD TV and smart phone development, bio-health technology, genetic engineering, aerospace engineering, and artificial intelligence. South Korea has reached a level of national broadband internet access that is second only to that of Iceland. Since 2020 South Korea has been second only to Germany on the Bloomberg technical research and development innovation list.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES AND DEVELOPMENT

Overview

Current discussions of scientific and technological development cannot be disconnected from the effects of these activities on the environment. Throughout East Asia, different geographic regions and cultural areas face different sets of problems and environmental challenges, though some issues, such as industrial pollution, climate change and resource extraction are common to them all, and indeed, are global issues. Although nature has been celebrated in poetry and painting in all the cultures of East Asia, and the views of animism, Shinto, and Daoism reflect the strong links to nature these societies have celebrated from the earliest times, the realities of modern industrial and post-industrial economies combined with heavy population pressures, increased consumerism, and global resource scarcity and competition, have created many stresses on the environment and awakened needs for the development of sustainable practices.

|

|

Japan and the Koreas all have relatively small populations, but they lack flat, arable land. In the early stages of their push towards industrialization and economic competitiveness in a globalizing, post-colonial world dominated by market economies, both Japan and South Korea went through what at the time seemed an inevitable stage of severe environmental abuse that included industrial pollution of air, water, and land. In the last two to three decades, both Japan and South Korea have made strides in mitigating this abuse and improving water and air quality, though isolated North Korea has continued to exploit its diminishing and increasingly polluted natural resources just to sustain its economy. China, struggling with air, soil, and water quality issues in its recent decades of tremendous economic growth, has recently announced plans to address environmental issues and has encouraged global cooperation in dealing with climate change.

Forest conservation is in effect in both Japan and South Korea, though construction booms in South Korea have impacted many once rural areas. Though development continues, much of northern Hokkaido Island in Japan, plundered for resources in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, has been designated as national parks. Both Japan and South Korea import lumber from Southeast Asia and North America to protect their own supplies. Seoul, however, has instituted a highly successful ecology program that has provided a green belt around the city. In once-polluted waters downtown, people now windsurf on the Han River and water birds are in abundance.

Rare species of animals and birds inhabit the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North Korea and South Korea, making a symbol of human conflict a boon for ecology. Although certain once-threatened animals such as sika deer and brown bears are increasing in Japan, one cause of disagreement with international conservation groups is the nation’s continued practice of whale hunting, with the whale meat used as exotic food. Overall, in both Japan and South Korea there is an elevated level of ecological awareness among both urban and rural people. This is reflected in a recent survey in South Korea that shows a decline in interest in illegal medicinal products from tigers, rhinoceros, musk deer, bear, and pangolin. This helps the country to comply with the goals of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).

As for energy and other natural resources, the pressures for regional and global control of oil have driven continued exploitation of oil resources off coastal Japan and in the South China Sea. Many worry competition for energy sources will lead to conflicts between the countries of East Asia and other countries in the Asia-Pacific area. A key feature of China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative is creating channels for oil, water, mineral, and rare earths extraction. Innovations in solar, wind, water, and nuclear-generated power, along with kinetic energy production by other means are all under intense development in East Asia in attempts to cut pollution and address energy needs.

In an interesting twist, East Asia’s population numbers are showing signs of declining. Japan’s population rate is falling rapidly and may plummet from an estimated 123 million today, to only 80 or 90 million by 2050. South Korea has among the lowest birth rates in the world and Chinese officials are concerned over the economic and social effects of a greying population and low population replacement in China. What effect the dramatic lowering of population will have on the economies, societies, political dynamics, technological innovation, and environmental issues in East Asia will likely be a major story of the mid-21st century and have world-wide repercussions.

The greatest conflicts between industrial development and the environment are being felt in China. In 2006 air pollution became so bad in China’s capital, Beijing, that the government had to use cloud-seeding explosives to stimulate rainfall and clear out the smog that hung like a visible shroud over the city for much of the year. As automobiles have grown in popularity over the last two decades exhaust has become a major contributor to air pollution, along with the burning of China’s number one energy resource: coal. Air quality issues exist in most major Chinese cities, including Tianjin, Shanghai, Wuhan, and Chongqing. China’s share of greenhouse gas production that contributes to global warming now rivals that of the United States.

As Chinese industry has expanded, both urban and rural water sources have come under intense pressure due to the unregulated and under-regulated dumping of pollutants. Also in early 2006, a massive chemical leak caused by a chemical factory explosion destroyed many miles of the once scenic Songhua River in northeast China, forcing the importation of drinking water for locals affected by the spill. Water problems have also decimated fish populations in the Yellow Sea area and driven the dolphins in the Yangzi River delta to extinction.

|

|

Unregulated mining, logging, and small industry affects water and air quality in many once pristine areas in more remote parts of China, much to the distress of local populations who see resources from their lands going to benefit the coastal cities. Other problems include increased desertification of northern China, in part due to overlogging, overgrazing, and abuses during earlier political movements. Despite attempts to reforest the edges of the expanding deserts, dust storms, decreasing range for animal herding, and the silting of the Yellow River (which in some areas barely flows) continue to be problems. Although China has banned the export of disposable wooden chopsticks to Japan and other nations, its growing timber interests in parts of Southeast Asia and insatiable appetite for building materials at home threaten to ravage some of the last untouched forests on earth.

|

|

|

|

|

|

While interest in ecology and conservation has grown in China over the last two decades, and government projects are underway to save the panda, golden monkey, and pangolin, there is still a strong underground market for endangered animal products (including tiger parts from Southeast Asia and gallbladders from black bears poached in North America). Legislation during the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020 saw new regulations against raising and marketing wild animal products.

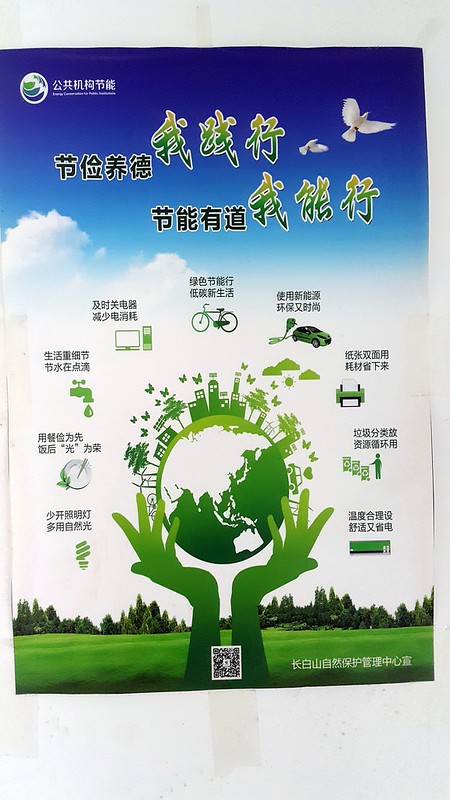

As China searches the globe for oil as part of the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, it is also experimenting with solar, wind, water, and kinetic energy technology on a massive scale. In parts of northwest China, many acres of desert are covered by stands of gigantic windmills, which presently fill only a fraction of China’s electricity needs but may hold promise for the future. Over the years a certain number of NGOs (non-governmental organizations) have been allowed to operate in China. Among the small-scale ecology and natural resource management NGO projects of the early 2000s was a solar cooker project started at the Xining Teacher’s College in Qinghai, northwest China. In the project, Tibetan nomads and villagers were offered solar cookers at discounted rates so that they do not have to rely on dried animal dung or scarce trees and brush for fuel.

Desertification

Desertification, the phenomenon of fertile land transforming into desert, is one of the major environmental issues facing much of the world, including China. Over one-quarter of China’s territory is covered by deserts. The UN Convention to Combat Desertification (CCD) began in 1994, and in 1996, China became an official member. Beyond the ecologic harm desertification brings to the inundated grassland of northern China, each year residents of eastern Chinese cities such as Beijing and Tianjin must brace for annual dust storms. In addition to having problems with breathing and dust that stings the eyes, people are constantly working to keep dust out of homes and to clean doorways and sidewalks of dust and sand. In 2021, Northern China suffered its worst dust storm in a decade. Two weeks later it was followed by another. The effects of the storms reached throughout South Korea and also Japan.

Battling the advancing desert is a difficult challenge for China. China has taken measures to reduce over-plowing in at-risk areas, has implemented vast tree-planting programs, and has begun to address the issues of overgrazing. However, this is not an issue easily or cheaply solved. Qu Geping, the former Chairman of the Environment and Resources Committee of the National People’s Congress, spoke out about the desertification problem as early as 1972, and later encouraged massive government funding. Halting the advancing deserts will require a massive commitment of financial and human resources, one that may include costly south-north water diversion projects and battle the advancing deserts that are marching eastward and could eventually occupy Beijing.

Air and Water Quality

China’s rapidly growing economy has brought both air and water quality issues. China is the second-largest emitter of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions after the United States. China’s share of world carbon emissions is expected to increase reaching 17.8 % by 2025. In 2001, China accounted for 9.8 % of world energy consumption. By 2006, China had become the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases and by 2009 it surpassed the United States as the world’s number one energy consumer.

Over the past decade, however, China has also become the world’s leading producer of renewable energy.

Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, China has implemented new laws and regulations for the environment, and the government has invested an increasing amount of resources in protecting air and water.

The twin problems of water scarcity and pollution in China are major issues. Not only do they threaten human health and development, but water problems also jeopardize China’s economic plans. In recent years water shortages in cities cause a loss of an estimated U.S. $11.2 billion in industrial output, while the impact of water pollution on human health has been valued at approximately $3.9 billion. Future economic development could be seriously jeopardized by water shortages.

In some places, the water shortages are extreme (China has about the same amount of water as Canada, with a population 100 times greater). In much of the country, the water is heavily polluted (exceeding national standards). And in still other areas, complicated by global climate change, flooding regularly surges out of control, wreaking havoc with crops and homes. China ranks fourth in the world in terms of total water resources but is second-lowest in terms of per capita water resource availability. Nearly half of China’s 640 major cities face water shortages. One hundred of them face severe shortages. Additionally, unable to use surface water in much of the country due to severe pollution or scarcity, groundwater is being depleted at a staggering rate. For example, in Shanghai and Beijing, groundwater levels have been dropping several feet per year. The maintenance of water resources is a challenge for most countries in Asia. China’s policy of damming rivers sourced in the Himalayas for electricity has repercussions for countries downstream, such as India, Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam.

In a report released in 1998 by the World Health Organization (WHO) listing the ten most polluted cities in the world, seven were found in China. The China 2020 report indicates an estimated 178,000 Chinese in major cities suffer early deaths because of atmospheric pollution in excess of international standards. It also reports 52 of 135 monitored urban river sections are contaminated rendering these sections essentially waste dumps. Acid rain in the high-sulfur coal regions of south and southwest China has the potential for contaminating 10 percent of the land area. Children in major cities were found to have blood lead levels that average 80 percent above the levels considered to be dangerous to mental development. In 1995, air and water pollution damages were estimated at US $54 billion per year— or at least 8% of China’s total GDP. In an effort to reduce air pollution in Beijing, the government in 1999 ordered city vehicles to convert to liquefied petroleum gas and natural gas. By 2002, Beijing had the largest number of natural gas buses in the world.

The new policies establish comprehensive regulations to curb environmental damage and place China in a “green” leadership role.

Eco-Technology: Solar Power and Wind Projects

Over the past two decades, the amount of energy and carbon consumed per dollar of GDP has decreased in China. Even with average annual GDP growth rates over 8 percent, China has been reducing its energy intensity, or increasing its efficiency, in terms of energy needed per dollar of growth. This is in large part due to the efforts by the Chinese government to conserve energy, and the adaptation of modern industrial plants to reduce coal and petroleum subsidies. After coal, renewable energy sources (including hydroelectricity) accounts for the second-largest share of China’s electricity generation. With assistance from the UN and the United States, China hopes to develop a multi-million dollar renewable energy strategy to combat pollution.

Wind sources are concentrated in the northern and western regions of China, as well as along the coast, and are suitable for both rural village electrification and large scale, grid-connected electricity production. The next highest wind potential region covers Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and northern Gansu Province. China has invested heavily in solar power and is the largest producer of solar panels in the world. Solar water heaters are a common sight on rooftops in many cities and solar has been a boon to herders and farmers living off the grid. Large-scale photovoltaic projects have been launched across the country, including relatively undeveloped areas like Guizhou province.

CASE STUDIES IN DEVELOPMENT AND SUSTAINABILITY

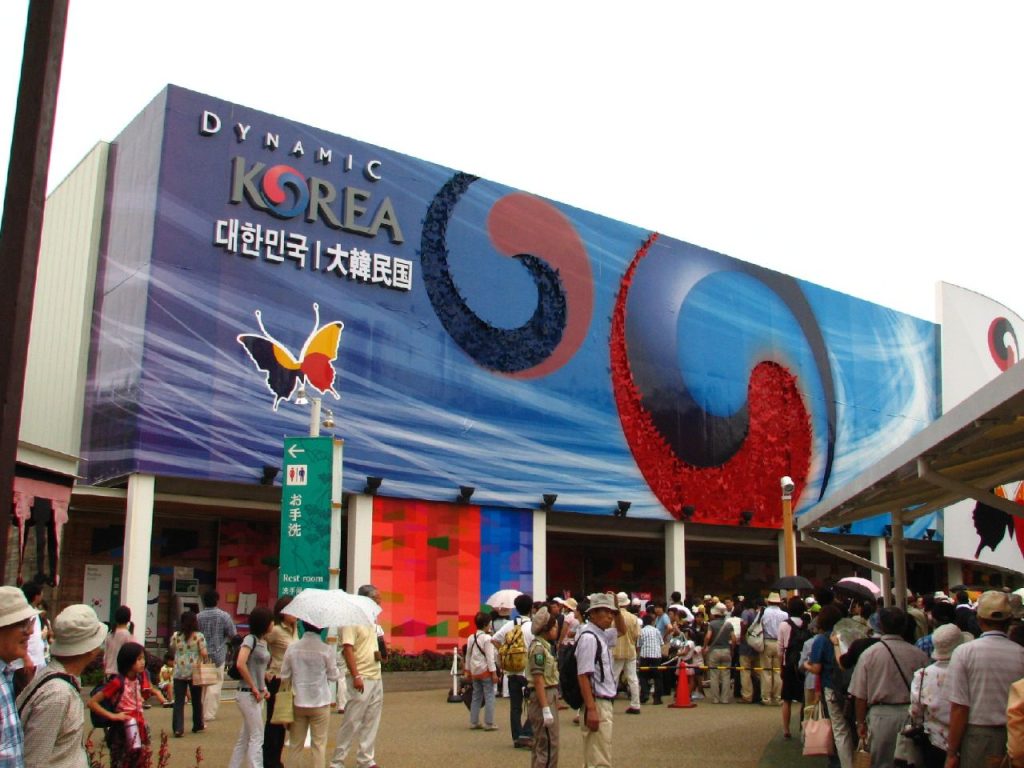

Expo 2005, Japan

The 2005 international exposition held in Japan from March 25 to September 25, 2005 was held in Seto City, Nagakute Town and Toyota City in Aichi Prefecture in an area covering approximately 173 hectares. Its stated goal was to transcend national boundaries, giving collective expression to the themes of the EXPO and present a “grand intercultural symphony” of the world’s peoples and cultures. The site was constructed with minimum possible impact on the environment in order to fully symbolize and express the EXPO’s theme: Nature’s Wisdom.

Countries from around the world participated in the project which featured pavilions reflecting traditional and futuristic themes from nations and cultures from every inhabited continent. A major exhibit was the Yukaghir Mammoth, an 18,000-year-old wooly mammoth that was excavated in Siberia and displayed in a specially built laboratory on the Expo site. The 40-something-year-old mammoth was kept at -15 degrees Celsius and was a major draw at the exhibition. The exhibition of the mammoth represented the need to care for the environment.

An important theme of the Expo was environmentally friendly technology. This was concretely demonstrated by the Japan Pavilion Nagakute in Aichi. The theme of the pavilion was, “Creating 21st Century Prosperity through Japan’s Experience—Let’s Grow Closer to Nature Again.” Covered with nearly 30,000 bamboo plants, the two-story structure appeared like a giant green cocoon. A major feature of the pavilion was the use of biomass technology (the use of renewable organic resources from plants and animals), which was demonstrated in several innovative ways. In the food courts, a biomass plastic made of biodegradable corn resin, clay, and scallop-shell powder was used for all the disposable tableware. After usage, the discarded bowls, plates, and cups were composted. The pavilion was completely powered by fuel cells that generated electricity derived from the five tons of garbage produced daily on the site. The garbage-generated electricity was augmented by a 200-meter series of solar panels outside the pavilion. The site also featured biomass toilets in which wastewater was reconverted into over 10 million tons of clean flushing water over the course of the 6-month exhibit.

Other exhibits in the Japanese sites at Expo ranged from a futuristic Earth Tower in Nagoya and exhibits of the robots, communications, and transportation of the near future. Osaka will host the Expo in 2025. In the last decade since the expo, several sustainable “smart cities” have been planned and constructed with the help of major private investors.

The Three Gorges Dam

Construction on what has been called the greatest construction project since the Great Wall, the Three Gorges Dam, officially began on December 14, 1994, after years of planning. The largest dam, largest water conservation project, and largest hydropower plant in the world was fully completed and functional by 2012. Conceived by Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Republic of China in 1911-1912, the dam is 1.4 miles long, 607 feet high. 35.6 million cubic yards of concrete and used 463,000 metric tons of steel in its construction. The workforce is estimated at 250,000 people.

The dam was built in Chongqing Municipality (population over 31 million), in an area of the upper Yangzi River known as the Three Gorges, historically one of the most scenic areas on earth. Although the water level rose about 100 meters to cover portions of that scenery, the 26 turbines in the dam have a combined output of 18.2 million kilowatts of electricity, enough to supply the energy needs of much of southern China, generating the equivalent of 18 nuclear power-plants.

In constructing the world’s largest dam, approximately 1.25 million people from farm towns and small cities along the gorge were forced to move to other areas, mostly at government expense.

Many valuable archeological sites of the ancient Ba culture are now covered by water, despite archaeological salvage operations. The effects on local plant and animal species (such as fish spawning) will be affected by the dam, as well as local water tables, are currently under study. Several preserves have been established to help save dozens of rare or threatened plants and wildlife. These include the Haiyun Botanical Park in Hubei province, which covers 6,987 hectares and holds 54 rare plant species. One species of tree, the giant metasequoia, is left over from the last Ice Age.

|

|

|

|

Another factor that scientists have had to tackle is the buildup of silt behind the dam. The dam created a four-hundred-mile-long lake, as long as Lake Superior. Engineers, however, are at work tackling the silting problem which has evolved in nature and effect over time. Besides generating energy, the dam is intended to help moderate the terrible flooding that has plagued southern China for millennia, and radically improve river transport to link developing inland China more efficiently with the booming coastal areas.

The Seoul Greenbelt

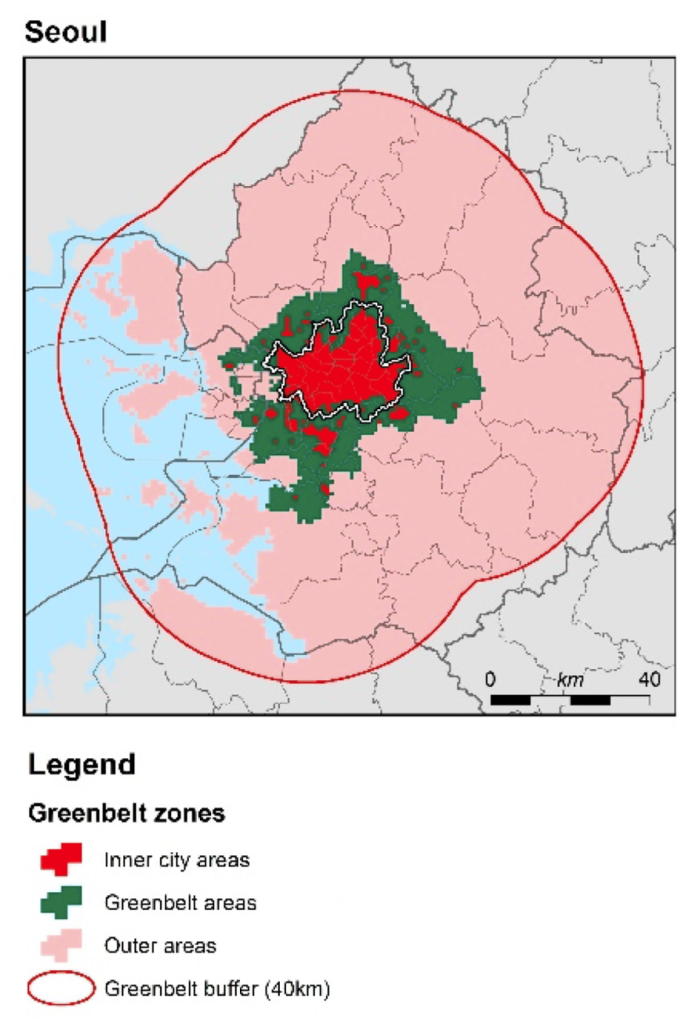

One of the most striking things about a visit to Seoul, an urban area with a total population of nearly 10 million, is the ready access to trees, rivers, and mountains from the city center. Urbanites can easily take trains, buses, cars, and SUVs to parks and other access points for family outings, hiking, climbing, camping and other nature-related activities. On weekends and holidays it is common to see families, friends, and classmates holding picnics along the mountain river banks, and people of all ages decked out in trendy mountain climbing gear heading for the nearby cliffs. This is all due to a greenbelt program started in 1971 in response to rapid growth when Seoul was the fastest growing city on earth (a title it held from 1950 to 1975).

A greenbelt is a corridor of natural land left around a city to stifle urban sprawl and maintain the quality of urban life. Seoul’s greenbelt is approximately ten kilometers wide and circles the city center. It has been heralded as the most successful greenbelt in Asia. The belt of forests, mountains, river valleys, and agricultural lands, was initially conceived of as a barrier from invasion by North Korea, a means to reduce rapid population growth and land speculation in the capital, and as a means of resource protection.

Over the years, the benefits to the natural environment have become the prominent reason for the continuation of the policy. Certain problems have emerged, however, mostly related to disputes over land ownership (80 percent of the greenbelt is in private hands) urban sprawl beyond the greenbelt, and congestion within the belt.

It is interesting that the greenbelt has a historical precedent in Korea. In 1397, at the beginning of the Joseon dynasty, King Yi Song-gye declared that the natural features around the capital were to be preserved out of respect for the spirits of the land; beliefs in fengshui (the principles of the inter-relationship between landscape, architecture, and human beings which is described in Module 3); and for future generations. It has long been a custom in Korea (and other parts of East Asia) for villages to reserve a grove of trees or part of a mountain for similar reasons.

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

- Japan

- Earthquake Proof Architecture – A TomoNews report on the various ways Japan has protected the integrity of their buildings from earthquakes

- Covid Mask on Buddhist Statue – A news report about one of Japan’s largest Kannon statues receiving a giant COVID-19 mask

- Seawalls – An ABC News deep dive into “The Great Wall of Japan,” a long, complex, and controversial breakwall meant to reduce the damage done by tsunamis

- Woven City – The official YouTube channel of Toyota’s ambitious project to build a sustainable smart city that will serve as “a laboratory for a better tomorrow”

- Literature and Contagion – The director of the National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) presents on the ways their project to digitize old Japanese texts can be used to sustain hope during disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic

- China

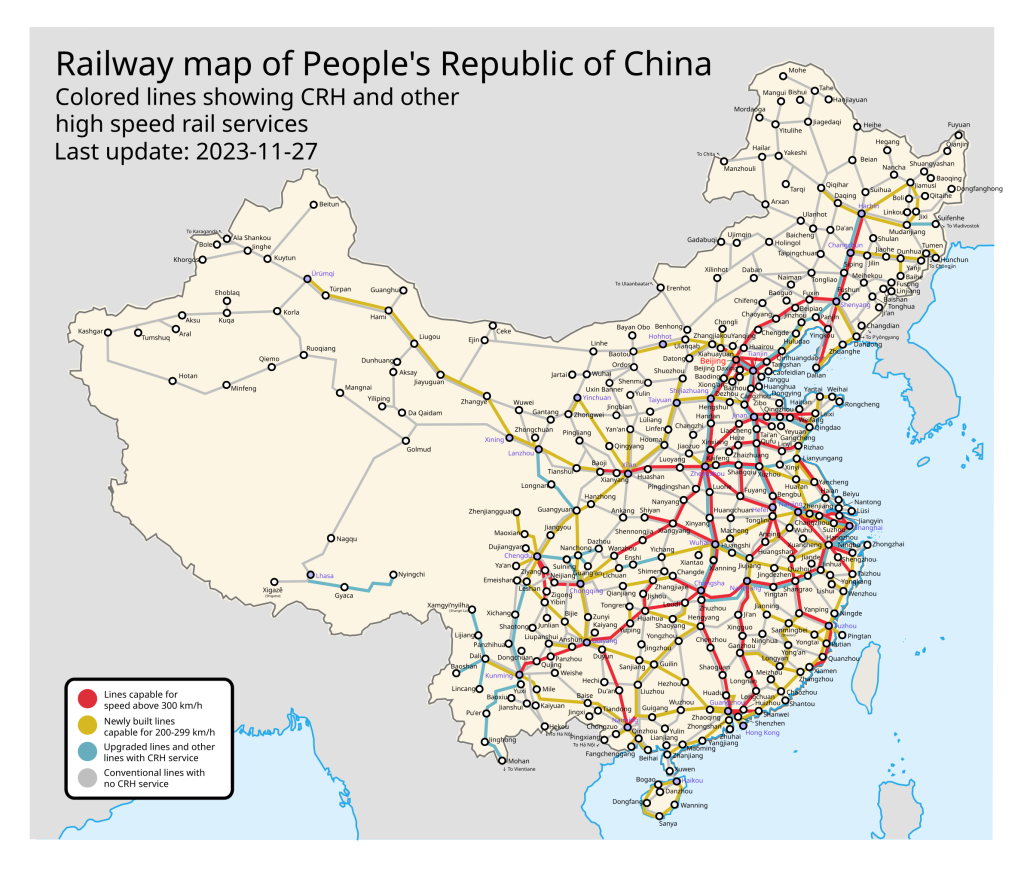

- High-Speed Railway – A news feature explaining how China constructed the most comprehensive high-speed rail system in the world

- Frontier Women – A short CGTN news report on the ways Chinese women have empowered themselves in the tech industry in recent years

- A.I. Revolution – A short documentary from 2020 exploring China’s high-tech vision for the future

- Qinghai Conservation – A CGTN news report from 2021 detailing Xi Jinping’s decision to make ecological conservation in Qinghai, one of China’s largest provinces geographically, a national priority

- Religion and Environment – A short documentary considering the possibilities for traditional Chinese religious perspectives as a way forward in environmental conservation

- Xiong’an, the City of the Future? – A China Daily article providing an in-depth description of Xi Jinping’s highly ambitious “smart city” project near Beijing. While the article presents a glowing progress report on the city, many people have criticized it for being an “expensive ghost town.”

- China’s Moon Base Plans – YouTube channel Dongfang Hour explains China’s plans for and progress on a lunar base, including exploration of the moon’s dark side

- Space Food Evolution – A short run-down of how China’s space program has fed its taikonauts since Yang Liwei was first sent into space

- North and South Korea

- “AlphaGo: The Movie” – A gripping documentary by Google DeepMind about the famous go competition between British-created AI and South Korea’s Lee Sedol

- Tech Savvy South Korea – A CNN news report asking the question “Is South Korea the most tech-savvy country in the world?”

- Eco Farming Technologies – A news report about how South Korea is turning to smart-farming technology both for ecological reasons and because South Korea lacks the labor force necessary to sustain its farms

- Samsung’s Digital City – A brief introduction to Samsung’s massive headquarters just outside of Seoul, which operates almost as its own city

- Busan’s Smart City – A short news report about Busan’s development of smart cities. In recent years, Busan’s mayor has also announced plans for further development based on the “15-minute city” concept

- Seoul Greenbelt – A news report about how Korea’s government reaffirmed its commitment to preserving the Green Belt restrictions around Seoul

- Other

- Liangshan Documentary– A Japanese film producer living in China visits China’s poorest area

- Genetic Landscape of Eurasia and “Admixture” in Uyghurs – An academic article about the genetic map of the Uyghur people