6 Module 5: East Asian Lifestyles

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

OUTLINE

INTRODUCTION

With the dramatic rise in living standards and the effects of globalization, over the last few decades life in East Asia has become increasingly multi-faceted and complex. Although the time frame and pace of development have varied between the countries involved, contemporary East Asia offers a fascinating mix of innovation, tradition, experimentation, and transformation in the arena of daily life. This module consists of snapshots of diverse aspects of the lifestyles in East Asia today, presented with the goal of giving a taste of the richness and complexity of life in the dynamic region. Specific topics explored by way of short essay, photographs, and video clips are built spaces and material culture in urban and rural areas; food culture in East Asia; traditional festivals; and college life in East Asia (with a look at the day in the life of a Chinese college student).

FOOD CULTURE

Overview

One of the most distinctive features of the East Asian cultures today are the rich and varied food cultures. As societies become more globalized, longstanding traditions are modified and new ways of doing things are invented and adopted. Among the many changes affecting virtually all aspects of life in East Asia, traditions related to food—what folklorists call “foodways”—tend to be among the most conservative cultural traits. Thus, despite the influx and availability of internationalized foods—such as spaghetti, tacos, pizza, crepes, and American fast foods like fried chicken and hamburgers—from outside the region, traditional foods still make up the majority of most people’s caloric intake in East Asia.

Rice is still the number one grain in most of the region, though large parts of northern China consume wheat products as a staple. In some upland areas in all three countries, other grains such as buckwheat, millet, corn, and highland barley also contribute to the diet. In any given cultural area, there is tremendous variation in food. While standardized food stores with plastic wrapped items and computerized checkouts have become popular in urban areas throughout the region, many people still enjoy shopping in traditional markets where small businesspersons have their own stands and food is very fresh—often right off the farm or directly from the sea. Walking through a traditional market is a sensory experience second to none and a great way to interface with a culture.

|

|

|

Examples of traditional dishes across East Asia. |

||

|

|

|

Food vendors and markets across East Asia. |

||

Cuisines of China

Despite the rich selections of foods in Korea and Japan, no culture on earth matches the Chinese for food diversity, breadth and variety. Traditionally, there are eight major food cultures among the Han Chinese alone, and many minority groups have highly distinctive cuisines and manners of eating. Famous cuisines are found in all the directions of the compass, and all points in between. The largest eight cuisines among the Han Chinese are Cantonese (Guangdong and parts of Guangxi) cuisine, Sichuan cuisine, Hunan cuisine, Zhejiang cuisine, Jiangsu cuisine, Shandong cuisine, Anhui cuisine, and Fujian cuisine, and even these groupings have local variations. In recent years, other cities and areas, such as Shanghai, Beijing, Xinjiang, and Northeast provinces have also developed distinctive local cuisines.

In general, northern foods tend to center on wheat, Chinese cabbage, and meats such as pork and lamb with few condiments except garlic, soy sauce, and dark vinegar. Favorite dishes are fluffy steamed bread called baozi filled with meat or bean paste; steamed, fried, or boiled dumplings filled with greens and meat paste (something like ravioli) called jiaozi; and hand-pulled noodles (lamian). A favorite northwestern dish from Gansu province is called big pan chicken (dapenji) and features noodles literally the length and width of a belt.

Cuisine from northern China |

|

|

|

|

|

As one travels farther west in China, the food becomes increasingly influenced by Middle Eastern cuisines. The Muslim peoples in the northwest have very distinctive cuisines that include the types of wheat-based foods just mentioned, as well as baked flatbreads (nang), noodle or rice dishes featuring lamb or beef, and spicy kebabs (yangrouchuan). Grapes and regional melons, such as the famous Hami melon, are common in local markets.

|

|

|

|

Food from Western China |

|

Food in the Yangzi River delta, including Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces, tends to be somewhat sweetish and bland, featuring clear soups, fish, rice, leafy vegetables, and lightly salted meat dishes. A favorite local food is known as “little cage buns” (xiaolong bao) a type of steamed round bread filled with a soupy meat and a vegetable mixture.

Cuisine from the Yangzi River Delta |

|

|

|

Like Korea and Japan, the cuisines of coastal China in general feature a wide variety of seafood—everything from fish, shrimp, and crabs to delicacies such as sea cucumbers, horseshoe crabs, the air bladders and stomachs of fish, sandworms, and a type of crustacean that looks like a cross between a praying mantis and a shrimp known as lainiao xia. Seafood is basic to the southern cuisines of Fujian province, Taiwan, Guangdong, Hainan Island, and with less variety, the northern areas around the Yellow Sea.

The Cantonese areas of Guangdong and Guangxi offer some of the most adventurous food experiences in China and hosts will often attempt to impress and please guests with the most exotic fare possible. This might include snakes, frogs, turtles, and a variety of wild mammals such as fruit civets. Cantonese people also love braising soup. It usually takes 3-4 hours to make a stew and the fire is set at a very low level. Different ingredients and Chinese herbal medicine such as red dates and ginseng are combined in the soup for different purposes in different seasons. For example, people who feel hot all time are believed to have too much yang in their bodies and are told to avoid putting ginger and red ginseng in their soup during the summer. For women who are pregnant or have just given birth, soup with angelica, red date, and Chinese red medlar (goji berries) might be recommended.

|

Cuisine from

|

|

|

|

|

A favorite food experience in the Cantonese areas is eating dim sum. Families and friends go together to restaurants on weekend mornings and sit at round tables. Servers arrive with small carts laden with a wide variety of steamed goodies such as shrimp dumplings, braised chicken feet, braised beef tendon, egg tarts, and other delicacies. Patrons order a whole table full of the various small dishes, each person eating a morsel or two from each. As in other Chinese eating contexts, the atmosphere is lively, with much loud talking and laughter.

Lychee nuts, longans, pomelos, pomegranates, papayas, mangos, jackfruit, oranges, tangerines, and several varieties of bananas and melons are among the many fruits enjoyed in southern China. A wide variety of cucumbers and squashes (including the famous “winter melon”, with whitish meat that is boiled in soups), leafy green vegetables, and other greens are also an important part of the southern diet.

|

|

|

|

Fruits from the Cantonese areas. |

|

Key ingredients in many foods in southwest China are red hot chili peppers (imported from Mexico centuries ago) and a strong, peppery seedpod known as huajiao, or Chinese peppercorn. It is said that it is because the weather in southwest China is humid and cloudy that pepper is used to drive out the dampness in the body and prevent arthritis. Therefore, hot pepper sauce is used almost at every meal, including breakfast noodles. Many locals have a difficult time adjusting to cuisines in other parts of China that do not require massive doses of hot sauce. In some marketplaces, sellers offer bags of powdered pepper by the kilo.

|

|

In Sichuan province, ground-zero for hot and peppery food, a common dish is spicy hot pot (huoguo). While hot pots are common winter fare in other parts of China (with equivalents in Japan and Korea), nowhere is the food served with more chilies. In some instances, diners must dip their chopsticks into a huge pan, probing through a thick layer of floating peppers and peppercorns (huajiao) just to get at the slices of fish and meat and the mushrooms, and vegetables lurking beneath.

In the cities like Chengdu (the capital of Sichuan) and Chongqing, many restaurants offer hundreds of small, delicious treats, called xiaochi in Chinese, and many repeat visits are required to exhaust the menu. Many xiaochi also have non-spicy version in case tourists from other places cannot tolerate the spiciness.

|

|

|

|

Varieties of “Little Eats” (xiaochi) from Southwest China. |

|

In Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province, a favorite food is known as “crossing the bridge rice noodle” (guoqiao mixian). Each diner is given a large bowl filled with steaming hot soup upon which floats a thin layer of cooking oil. Patrons are also supplied with plates of finely sliced raw meats, fish, and vegetables which are slowly stirred through the near-boiling water. The layer of oil traps the heat to maintain a cooking temperature, thus allowing each person to cook their meal themselves.

The food cultures of China’s many ethnic minority groups vary widely. Boiled lamb, cheeses, salted milk or butter tea, and yogurt are popular foods in Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and some other parts of northwest China. A staple of Tibetan cuisine is roasted highland barley flour called qingke. A small amount of buttered tea (made by churning butter and tea) is poured into a bowl of barley powder. The mixture is kneaded in one hand into a dough known as tsampa, and eaten along with yak meat or sausages, if available. Another Tibetan favorite from Sichuan, is a kind of baked meat pie consisting of a layer of dough filled with yak meat and covered by another layer of dough, much like a small apple pie.

|

|

|

|

Food from Tibet and Xinjiang |

|

Dishes featuring sticky rice, smoked or salted pork, chicken, and pickled fish and vegetables are popular among peoples of the southwest such as the Miao and Dong (Gaem) people of Guizhou, the Zhuang people of Guangxi, and the Dai people along the borders of Yunnan and Southeast Asia. Sticky rice is just as the name implies—sticky. It has a high gluten content and therefore sticks together much more than usual rice. It is often boiled with some fatty meat or bean filling in lotus, bamboo, or banana tree leaves; sometimes it is steamed inside bamboo tubes. Among the Miao people in the southeast part of Guizhou, there is a special festival called “Sister’s Rice” in which all the unmarried young women in a village gather to wear their finest clothing and eat a special feast featuring colorful sticky rice and other dishes.

|

|

Varieties of Rice from Guangxi, China |

|

Among the most unique eating arrangements is that of the Nuosu (Yi) people of the Liangshan Mountains of Sichuan. Basic foods include boiled chicken, potatoes, a soup made of dried greens and bean curd, and steamed buckwheat pancakes. Traditionally, two large serving bowls are placed on the ground – one for soup, and the other for chunks of meat, buckwheat cakes, and potatoes. No one has an individual bowl, though each eater has a large, specially shaped wooden spoon called an ichyr. The spoon is unique in that the handle is attached to the side of the spoon (rather than one end). This way it is easy to dip into the soup bowl and sip from the end of the spoon, rather than the side. Family members or guests politely squat around the bowls and gingerly pick up chunks of bony meat by hand or dip the spoon as needed. At weddings or funerals, large numbers of guests can be seen eating this way at the homes of relatives in the community that have pitched in to help feed the guests. And since there are only spoons and large bowls, clean-up is relatively easy.

|

|

|

|

Nuosu (Yi) dishes feature big chunks of meat, buckwheat cakes, green beans, and potatoes. These dishes were served in a Yi restaurant and therefore are not put on the floor, as in traditional homes. Note the painted wooden spoon (ichyr) in the top left image. |

|

|

|

Cuisine of Korea

Among the foods of the Korean peninsula, none is more famous than kimchi, a spicy pickle made of Asian cabbage, giant white turnips, and other vegetables. Bright orange in color and strong in flavor and taste, several tiny dishes of various types of kimchi are served with every sit-down meal in Korean restaurants.

There are over a hundred types of side dishes. |

|

|

|

Aside from fish and seafood, popular Korean meat items are chicken, pork, and bulgogi, a dish made of thinly sliced beef that is sautéed with a savory sauce and onions. Both bulgogi and a dish made of beef ribs, called galbi, are often served at small tables featuring a grill where patrons can cook the meats and accompanying vegetables to their taste. Those newly arrived in Korea will find it interesting to see fellow diners wielding large scissors to cut up meat.

Unlike the very pointed chopsticks used in Japan, and the long bamboo or wooden chopsticks of China, Korean chopsticks are made of shiny metal, a custom dating to ancient times. Koreans also use a unique metal spoon with a long handle and a wide flat end used for sipping soup served at very hot temperatures, especially in winter. Also, unlike Japanese and Chinese who may lift their rice bowls from the table when eating rice, polite Koreans leave their bowls resting on the table.

Korean fast foods, once served at small roadside inns include beef broth soup, ramen noodles (served hot or cold, depending on the season), and a mix of rice, egg, red sauce, and various vegetables are known as bibimbap. Another Korean favorite is kimbap, finger food that consists of rice with seafood and vegetable filling rolled in layers of dried seaweed—similar to Japanese sushi. In summer, a type of noodles called naengmyeon is served cold, sometimes with ice cubes added to the soup!

|

|

As in Japan and China, a favorite evening activity is strolling through the streets sampling foods from several stands or small shops found in certain districts of the city that stay open late at night.

|

|

|

|

Cuisine of Japan

While Japanese cuisine may not contain the breadth of variety that characterizes that of China and continental Asia, the island nation still boasts some of the most delicious and beautifully prepared food in the world.

The focus of Japanese food, like Japanese culture and history, is on rice. Rice is traditionally the centerpiece of a Japanese meal. Several small side dishes are provided to complement the rice, the most common of these being fish. Japanese history and culture are defined by the status of the area as a group of islands, and the food culture of the Japanese is no exception to this. Sushi, raw fish served on a small bit of vinegar flavored rice, and sashimi, carefully cut slices of only the raw fish itself, are perennial favorites of Japanese people and are the most famous forms of Japanese food abroad. However, the standard method of fish preparation is simply grilling or broiling. A slice of fish or the whole small fish itself is usually served along with miso siru, fermented bean-paste based soup, rice, and various tsukemono, or pickled vegetables, (white radish or cabbage being the most common). While Western-style food is served more often in Japanese homes than ever before, the above combination is the standard for Japanese food culture both in the home and in restaurants.

Despite Japan’s small size its food tends to be highly regional. Each individual area, city, and town will boast its own certain specialties, such as a certain fish, mushroom, or vegetable. One well-known example of this is the large crabs served at hot spring resorts in Ishikawa prefecture, located on the East Sea (Sea of Japan).

The tofu, or bean curd, in Kyoto is considered the best in the nation. Real Japanese bean curd has its own wonderful flavor and texture. One of the most distinctive foods in Japan can be found in the large port city of Osaka. It is called okonomiyaki, which can be translated literally as “what you like to cook.” Cabbage is chopped and mixed in a bowl with egg and a type of potato starch before being fried on a large hot skillet. Often chopped shrimp, squid, and/or octopus is mixed in before frying, while pieces of thinly sliced pork are popular additions to the final product. Fried noodles are often added as a second layer to this pancake-like dish. A richly flavorful sauce then tops the entire dish. Restaurants specializing in okonomiyaki are some of the most colorful and lively to be found in Japan. The city of Hiroshima also has its own distinctive form of the dish known as Hiroshima-yaki or “Hiroshima fry.”

As with the rest of East Asia, there are several different types of noodles in Japan. These range from thin rice noodles and transparent root starch noodles to buckwheat noodles called soba. Soba can be eaten in a variety of ways but one of the most popular is to enjoy it chilled with a soy sauce-based dipping sauce. Horseradish paste or wasabi is often mixed into the dipping sauce along with sliced green onions and sometimes even a raw quail egg. Dried seaweed usually tops the noodles. This is a common dish during the oppressive summer months. Chinese style noodles, known as ramen, are a popular food as well. The pork-based soup broth for ramen usually takes over a day to prepare and the quality of this broth is considered the defining factor in the caliber of the dish. The heavy miso (fermented soybean paste) soup broth noodles found in the city of Sapporo are considered the best by some ramen aficionados.

The most splendid form of Japanese cuisine to be found throughout the country is kaiseki ryori. One definition of this type of cooking is “tea-ceremony dishes,” as they were initially served as small vegetarian side dishes during the tea ceremony as perfected by Zen Buddhists during the medieval era. Kaiseki refers to a heated stone held in the inner pocket of one’s robes. The most common explanation of this usage states that Zen monks, engaged in intense meditation and fasting, would place a heated stone in their breast pocket to ward off the pains of hunger. Today kaiseki ryori combines several disparate elements of various regional banquet cultures in its preparation and presentation. It is most often served at traditional-style inns or restaurants that specialize in it. The price range for the basic course of kaiseki ryori for one person can range from relatively reasonable to inordinately expensive, depending on the prestige level of the inn or restaurant.

The dishes may be simple, tastefully arranged affairs served on well-matched ceramic dishes or they can be intensely ornate miniature works of art presented on expensive china. The following are the most important elements in any course of kaiseki ryori: overall harmonization of individual flavors and ingredients within all the dishes; attention to and representation of the current season through the ingredients of the dishes and their presentation; and accentuation of local delicacies and specialties during the meal. These aesthetic themes in the preparation and presentation of food are not unique to the kaiseki ryori of Japan. They are central to the material culture of East Asia as a whole.

Probably the most daunting of Japanese seafoods is fugu, or pufferfish, revered for its taste, but feared for its deadly poison sac that must be removed by an expert chef (who also has a good insurance policy!).

Beef is a relatively new item on Japanese menus—its common use dating only to after the late 19th century. It is now an important ingredient in the boiled meat and vegetable dishes known as sukiyaki and shabu-shabu. Some of the best homegrown beef comes from the vicinity of Takayama in Hide Prefecture.

|

|

Sukiyaki (left) usually consists of thinly sliced beef, tofu, mushrooms, rice noodles, and other ingredients boiled in a hotpot at the table. Shabu-shabu (right) is generally similar, but is more savory |

|

One interesting aspect of dining in Japan is that in front of each restaurant is displayed the price and life-like model of all the foods on the menu. Thus, even if you do not speak Japanese, you can point to an item and soon have it sitting in front of you awaiting your eager chopsticks.

|

|

Excellent places to try a variety of Japanese foods are the food emporiums located in major train stations. Hundreds of small shops and concessions offer a dazzling variety of colorful and artistically presented foods. It is easy to buy a box lunch (bento) filled with succulent goodies before boarding a train and enjoy a quiet repast as the scenery breezes by. Unlike the Chinese, who eat communally by all taking food from each dish on the table, Japanese favor individual servings, so a box lunch is similar to eating at home or in a restaurant.

The common name for any type of alcoholic beverage in Japanese is sake, meaning simple alcohol. However, this is usually used in reference to rice wine. Another name of regular rice wine is nihonshu, “Wine of Japan.” Rice wine is further classified based on the size and processing of the grain of rice before it is fermented. As with other food cultures in Japan, the brewing of rice wine in Japan is highly localized. Each prefecture usually boasts of its own brewer of high-end traditional rice wine. Local rice strains, freshwater springs, and the quality of the soil in the rice patties themselves are cited as being the major factors in defining the taste of various local wines. Another type of alcohol brewed in Japan, distinctive from nihonshu, is shochu. Shochu is a cousin of the rice wine of Korea, soju, in both flavor and history. Outside of traditional spirits, Japan has a thriving industry producing western style liqueur and beer. The first beer brewery in Japan was founded in the late 19th century on the northern island of Hokkaido.

So, How Do I Eat?

On a visit to East Asia, you will have many chances to eat local cuisine. We have already outlined some of the foods and foodways you might encounter. But what do you do when you are directly confronted with a way of eating unfamiliar to you? Since food and its consumption is such a central part of every East Asian culture, as a visitor, your chance of being in a food situation that demands knowledgeable participation is high. The following paragraphs give some basic tips on what to expect and how to respond when you are invited to eat in East Asia or an East Asian setting. These of course are just general guidelines—local customs will prevail. So, in a real-life situation be prepared to be flexible. One good way of learning how to deal with food customs is to go slowly and watch what others do. It is wise not to just grab things and start eating or you may make a fool of yourself and embarrass your hosts.

Korea—Mealtime

The fantastic scenes of the cooking contests between female cooks in the now-classic 2003 TV drama “Jewel in the Palace” brought a new awareness of Korean food to Asia and other parts of the world. While that drama dealt with food in the court of an 18th century Korean king, Korean food today is just as exciting, as are the unique customs surrounding its consumption. While certain aspects of Korean food and table manners are similar to those of China and Japan, anyone participating in Korean meals must be aware of specific Korean customs—substitutions from surrounding cultures won’t do! At some point in your visit to South Korea, you may be asked to eat in a private home, though most people prefer to entertain in one of the myriad restaurants found in any urban area. Though customs vary according to locality, context and social class, aspects of the dining process are similar everywhere in the South Korea. The following paragraphs give some advice on eating in homes and restaurants. Remember, however, that these are just general guidelines—expect variation in these customs among individuals, families, cities, and regions. (Given the unlikelihood of us eating in North Korean homes any time soon, we are limiting this discussion to the South, though some customs are similar.)

First, if you are invited to a home, it is proper to bring a small gift. This may be a small item from your own country, some nice pieces of fruit, flowers, or a seasonal gift set sold at shops and department stores.

If you are arriving at a host’s home alone, knock on the door and greet the host (or whoever opens it) with the words “An nyeong ha se yo” followed by “Ho dae hae ju syeo seo gam sa hap ni da” which mean “Hello,” or “How are you?” and “Thank you for inviting me” in Korean. (There are other varieties of greetings, but these are most basic.) You will then be invited inside. The first thing to do is to respectfully hand your gift to the host, who will insist that you didn’t have to bring anything. Sometimes your host may insist that you take back the gift for your family or for yourself, but this is just to show that having you as a guest is more than enough—at any rate, keep pressing politely until the gift is accepted. Once your host or hosts have taken the gift, however, don’t be surprised if they do not immediately open it. Also, it is not necessary to ask questions like “Do you like it?” As this transaction is taking place, you will also be slipping off your shoes and poking your toes into the slippers that have been provided to you. In very traditional homes, however, you may just go in stocking feet—so no holes!

You will then be invited to sit in the living room, or the main room. If your host has a Western-style living room, you will be sitting on a sofa, but if your host lives in a traditional Korean-style house, you will sit on the floor, maybe on a small rectangular cushion. You will probably be offered some fruit (though certainly not what you brought as a gift!) and or tea, and members of the host family will keep you company until the meal is ready.

As mealtime approaches, food will either be arranged on a common table or each person may have a small table set in front of them on the floor, though the latter way is much more common in restaurants. If there are many guests, there will be several common tables.

Depending on whether at home or in a restaurant, food will be laid out in front of each participant as follows: a bowl of soup to the right, a bowl of rice to the left; one or more main dishes in bowls directly at the center of the table or in front of the guest; and a few smaller bowls containing side dishes that may be shared by two or more people. These side dishes usually include some form of kimchee (the spicy pickled treats introduced above).

Eating implements will be the pair of metal chopsticks and the flat metal spoon (also introduced above). The chopsticks can be politely laid side by side directly on the table, though in some restaurants special chopstick holders are provided so that the tips of the chopsticks do not directly touch the table. It is proper to place the chopsticks to the right side of the rice bowl. The metal spoon is carefully dipped in the soups or used to transport pieces of food difficult to grab with the chopsticks. Since the main meat and vegetable soups and dishes are served very hot, the flat spoon allows for the liquids to cool just enough so that they are warm, but not too cold when entering your mouth.

1) The eldest family member or the person of the highest status eats first.

2) It is best to start with a bite or two of plain rice, then try a side dish or two.

3) Do not take food from the same bowl twice in a row—vary your eating pattern.

4) Although some eaters (especially males) can be very vigorous, use some restraint in consuming the food—follow the pace set by your hosts.

5) Never pick up your rice bowl, or any bowl for that matter. Learn to eat the rice in the bowl while it remains on the table. (This is a major difference between Korean customs and those of China and Japan.)

6) When eating rice, consume from the portion of the bowl closest to you and gradually work your way out to the side away from you.

7) It is impolite to make slurping sounds when eating soup, especially for women.

8) Do not dangle your food into your mouth by tilting your head.

9) It is best to finish your rice. No need to try to finish the side dishes.

10) A small dish may be provided for bones or shells.

11) After the meal you should make a compliment about the food and thank the host and his/her family for inviting you.

Korea—Makgeolli, Soju, and Social Drinking

Alcohol plays a role in many social situations in South Korea, especially among businesspeople, schoolmates, and friends. Depending on what is available and the situation, a variety of drinks may be consumed. Aside from Western-style beer, whisky, vodka, and mixed drinks, among the common traditional drinks are a cloudy wine made of fermented boiled rice known as makgeolli (once popular among farmers) and a medium strength distilled alcoholic drink (made of rice, barley, tapioca, or sweet potatoes) known as soju. The hardest part of drinking in Korea is not dealing with hangovers. Rather, it has to do with how social hierarchies and the concept of “face” play out in drinking situations.

Whether at a bar, a restaurant, or a karaoke lounge (still favorite places for young people to gather to sing all over East Asia), drinking protocols must be followed in order to maintain one’s status in a group and to avoid offending persons of other social positions—especially if such persons are older in or in higher status positions. One common ritual is older college classmates taking younger classmates for a night on the town—which almost certainly will involve some drinking of alcohol. The role of the older classmates in Korea is that of protecting and aiding the younger ones—an expression of the stress on group over individual discussed elsewhere in the modules. However, people in lower social positions must offer respect to their benefactors—which may include allowing themselves to be the object of jokes or teasing during the drinking rituals. More than one (of the younger group) has been asked to pour a bowl of makgeolli dregs over their head for the amusement of their “protectors”!

As for who serves whom and when, there are many subtleties to these aspects of special drinking occasions. Customs vary among men and women, businesspeople, and schoolmates (especially those of different class ranks), and friends. The following are just a few general guidelines.

Japan—An Evening Dining Out with Coworkers

Group dining in Japan is an excellent demonstration of the social dynamics that are fundamental to Japanese society. The most common of these is an evening out after a long week of work with one’s coworkers. Harmony, unity, and proper decorum among co-workers is a cornerstone of Japanese society. Be it workers in the central office of a large corporation, the teachers at a suburban junior high school, or a group of construction workers, an evening’s dining is an important event that helps build relationships. A person’s proper role in such a situation, even one of relaxation, is important to consider. Despite this, the atmosphere of such an event allows people, although strictly divided by hierarchy within their working environment, time to get to know each other better.

For an organization such as the office workers of a suburban board of education or the teachers at a public junior school, an evening out usually starts after work ends on a Friday. Coworkers meet at a nearby train station in the late afternoon. Once everyone has gathered at the assigned location a junior member of the organization makes sure everyone is accounted for and being ushered onto the proper train. The same procedure follows upon arrival at the destination. Junior members of the office or teaching staff lead the group to the restaurant, where they work out the final details of the evening with the staff there. A usual destination for such an event is often an inn or restaurant specializing in a course of kaiseki ryori. At the restaurant, junior members make sure everyone is seated in the proper place in the tatami room. Sometimes names are drawn at random and people who do not usually work together are seated next to each other. This allows people who do not usually have the chance to speak to each other a chance to mingle in a neutral social setting.

Once everyone is settled and ready for the evening, several bottles of beer are brought in by a waitress, which are distributed to junior members of the group. A bottle is positioned between the low individual tables, usually one bottle to two people. Between the two people the one who is junior in rank, or if equal in rank the one who is younger, pours the senior person a glass of beer. Once everyone has a full glass of beer, the junior member of the organization with the most seniority announces the commencement of the evening’s relaxation. They then call upon the most senior member of the party, in our case the superintendent of schools or the junior high school principal, to make a small speech addressing the group. After a few words thanking everyone for working hard during the past few months, everyone raises their glass and with a rousing chorus ofkampai, “a toast,” every member of the group takes a drink. The atmosphere then becomes very relaxed as the servers bring in one dish of the course of kaiseki ryori after another. People make small talk amongst each other for a time, commenting on the dishes being served and so forth.

Rice wine is brought in with the food itself, usually with the first or second dish of the course. Junior members of the group take the rice wine (or a bottle of beer if someone has already gotten to rice wine bottles first) and then move around the group to the senior members. Sitting in proper seiza position on their knees, they then pour rice wine for the senior member. The senior member usually comments on how hard the junior member is working and offers them encouragement. They then pour the junior member some of the wine, often patting them on the back and urging them to have a drink as well. While the pouring of wine by the junior member to the senior member is an act of submission and deference to one in a higher position, the pouring of wine by the senior member to the junior member is a recognition of the pains taken by the junior member in their service not only to the senior member but to the group of workers. Simple social rituals such as this are extremely important in maintaining and improving group dynamics. While this may seem like a large amount of drinking early in a meal, the role of wine etiquette in social situations throughout East Asian history should be considered. Writings on proper wine etiquette at formal social functions at Court can be found as far back as the Shintei shushiki, or “Newly Established Wine Etiquette,” written in 818 by court scholar Sugawara no Kiyokimi. Such documents were compilations of scholarship derived from the study of Confucian ritual used at the Chinese Tang imperial court where the practice was seen as instrumental in establishing proper order and socialization among the Confucian gentlemen scholars whose job it was to run the state.

By this point in the evening, the middle course of dishes is being served and everyone is enjoying the delicious food. The atmosphere is now very relaxed, and coworkers can enjoy each other’s company in a much more intimate and convivial setting than the office or classroom. After the final course has been served and everyone has finished their meal the most senior of the junior members announces the second stage of the evening. Most often this is a trip down the road to a snack bar where a senior member of the group is well known: he is often one of the older men in the group and has several bottles of high-quality spirits reserved for him at the bar. After relocating to the snack bar, the bar attendant takes down the senior member’s designated bottles and serves each group member. At this point the male members of the group are enjoying their cigarettes. In East Asia smoking is a common form of ritual bonding among men and it is often hard for non-smokers to escape, though social expectations are changing. Typically, there is no expectation for women to smoke, although some may indulge in certain situations. Health consciousness regarding smoking has increased in recent years.

All snack bars of this type have a fully stocked karaoke machine. The phenomenon of karaoke originated in Japan during the 1970s and is mandatory for the second stage of an evening out with coworkers. While pop music is preferred by college or high school students, the most common type of music sung by adults in this social setting is enka. Enka is a genre of popular folk songs that originated during the 1920s and 1930s. Themes of enka usually involve deeply moving and sorrowful love, loneliness, and sensitivity. These are the very same themes that occupy the primary positions of Japanese prose and poetry as far back as the Kokinwakashu, or Collection of Japanese Poems New and Old, the first imperial anthology of Japanese poetry, which was compiled in the 10th century. People clap along and join in to sing the chorus to songs by each individual. Some enka songs call for both a man and woman to sing dueling parts in a love song. When such songs are sung the group reacts with great enthusiasm to the drama unfolding in song.

Usually, the second stage at the snack bar is the end of an evening out with coworkers. Sometimes, younger members of the group head into the downtown area of the city or town to continue the festivities. Often this is when most people head back to the train station together and proceed home. An evening out with coworkers in Japan is not to be missed. It is a great opportunity to not only see a vital element of Japanese culture firsthand but also a chance to interact with native Japanese on closer terms than are usually afforded during work or even visits to their homes. One’s own participation in the serving of wine or enthusiasm in karaoke are taken as demonstrations of affection and service toward the group and will greatly aid in your daily life in Japan. (Original text by Matt Chudnow)

China—If You are Invited to Eat

In China, you may be asked to eat a meal at a private home, be invited to a banquet, or more informally be taken out on the town to eat street food offered in small shops and stands. Customs vary quite widely according to ethnic groups. The following advice is generally useful throughout China, though some of the practices are more specific to general situations in predominantly Han Chinese areas. Although specific to a meal in a family home, this advice is also a basis for behavior at banquets—although banquet protocol can be somewhat more complicated and may involve the drinking of alcohol (for those of legal age).

If asked to eat in a private home (say by a classmate or friend) make sure you bring a small gift. This might be something from your own country, or a box of snacks, or several pounds of fruits. Very likely your friend or someone in their family will pick you up and take you to the home (which may turn out to be their parent’s apartment). Respond cheerfully when you are greeted at the door by your hosts. Once inside you will be asked to take a seat in the sitting room and will be given a cup of tea or soft drink, and a plate of fruits that are washed, peeled, and cut. It is customary to politely refuse anything offered—you will usually be offered it again. This protocol can be kind of tricky, so until you are used to it, just accept whatever is offered with a smile and a “Thank you!”

Also, it is better not to drink your tea right away, as it may need several minutes to steep and allow the tea leaves to soften and expand (tea bags are not commonly used—the best tea is dropped in loose pieces into a cup, then covered with scalding hot water to release the flavor).

Never be too quick to grab anything that is offered and never take more than a small quantity of what is offered (as it may seem greedy). Depending on the number of people around, you may suddenly be left alone for some time while your hosts prepare the meal—don’t fret—they have not forgotten you. It is not necessary to ask if you can help. Your only duty is to sit there and enjoy your tea.

When you are called to the table, do not just sit down anywhere you like. Simply stand there politely and you will be directed to your seat. Do not just start picking up spoons or chopsticks. As always, it is best to go slowly and respond to the directions of the host. Several family members may be present at the table. You may pleasantly acknowledge them with a smile and a slight nod of the head.

As you sit down you will probably notice that there are between 8 and 12 plates of food on the table. (Recent government guidelines limit number of dishes at some events and venues.) These are to be eaten from communally. Do not pick the plates up and start passing them around! And never, ever pick up a dish and scrape or slide portions of food into your bowl. Leave the serving dishes where they are! Thus, no need to say “Please pass that plate”—as there is nothing to pass! Since round tables are common, you will need only to extend your arm. If things are out of reach, don’t worry—someone will solve that problem for you. But we are getting ahead of ourselves …

Steps in Eating at a Chinese Meal:

1. The host will pick up his chopsticks as if to eat but, urge you to eat something first. Say a polite “Thank you” and use your chopstick to pick up a small piece of food from a plate near you.

2. Transfer the piece to your bowl (rice may already have been placed inside—if so, place it on the rice). Wait a second, then pick it up and put it in your mouth. Do not grab it and put it directly in your mouth. Do not pick around in the dish—zero in on a small of medium-sized piece and take it—do not take the largest piece on the serving plate. You will be regarded as polite if you follow this protocol—and a greedy, unrefined “large child” if you do not.

3. Once the guest has taken a morsel, others will then start picking up pieces of food and eating them. You may proceed to get another piece from another plate. Do not keep taking from the same bowl—you must take a bit from each plate.

4. The trick is to go slowly—meals are to be enjoyed. There may be some light conversation, or people may concentrate more on the food. Praise the food for its good taste or nice presentation if it is homemade, because you are praising the hosts’ cooking skills. You don’t have to do this if eating in a restaurant. In many cases, if everyone relaxes, the atmosphere will be convivial and even exciting. If someone makes light jokes about you or teases you, be a good sport and laugh along with everyone else. You will endear yourself to your hosts.

5. As noted above, never, ever pick up a plate and shovel or scrape food into your bowl. It is considered disgusting and uncouth behavior! Your hosts will be shocked (though they probably won’t say anything—at least not while you are around!)

You will have to use your hands when eating Beijing Roast duck. You are supposed to use the flat cake to wrap one or two pieces of duck, then add a piece of cucumber and some green onion (both picked up with chopsticks), dipped in sauce, and placed in the pancake.

6. Never lick chopsticks. Never pick up food with your hands, unless you see other adults doing it. In some cases, you will see people picking up part of a piece of food (say a chicken leg, or crab) with chopsticks and lightly holding part of it between the thumb and forefinger—you may imitate this.

7. In some cases someone may put a piece of food in your bowl—in fact you may have your bowl filled up—especially if you are being polite and eating slowly. Don’t be upset if this happens. This custom shows that your hosts care about and respect you. Try to eat some of it. If this is your first visit to the home, you may be overwhelmed with such “food caring” behavior. You are not really expected to eat it all—but do your best. You do not have to try and reciprocate by putting food in anyone else’s bowl—though later this is a skill you will want to learn—once you figure out when it is appropriate.

It is very common for a host to pour drinks and tea for the guest. A server usually helps with tea, soft drinks, or alcohol in restaurants. If you are having dinner in a family situation, do not expect any liquid except soup (though some families are exceptions). Alcohol may be served at festivals. In most of China, tea is not a normal table drink at home. (It is consumed before or after a meal.)

8. Always remember that your host has probably spent a small fortune on the feast—far more than a Chinese guest typically gets at an American home. This small feast is in your honor—giving face to both you and the host and acting as a bonding ritual. It isn’t just about eating.

9. It is OK if you make small slurping sounds when eating the soup, which may be served first or last depending on local custom.

10. Be aware that fish, chicken, etc. are served with the bones (and often whole, including heads and tails). Small bones from fish, fowl, and ribs may be gracefully removed from your lips with the chopsticks and deposited directly on the table or on a small plate for that purpose. (See what others are doing—methods for bone disposal vary, so it pays to go slowly and covertly observe!)

11. Also, don’t count on being served anything to drink during the meal—in some families, the soup (usually very thin) is the only “drink.” You may spoon small amounts into your bowl after eating your rice. Again, see what others do.

12. If alcohol if offered, politely refuse at first. If the host persists, drink as little as possible. (It is easier for women to refuse drinking alcohol than men—however, much depends on the actual situation.) Don’t allow yourself to get tipsy or drunk. Until you become more familiar with drinking protocol, take only very tiny sips if you are toasted. That is, don’t take the phrase ganbei —“bottom’s up”—literally.)

13. When eating rice, you may pick up your bowl and politely use your chopsticks to slide it into your mouth. Watch others. Many people—especially at banquets—eat little or no rice before the very end, when they top off the meal with a bowlful.

14. If at some point your host asks if you would like more rice, say yes only if you think you can finish it. Don’t leave a rice bowl half full—in fact, it is better to consume every grain. Some families still abide by the notion that “every grain of rice is a drop of sweat from a peasant’s brow.” On the other hand, despite recent government guidelines concerning frugal eating, you may observe that huge amounts of food are left on the table after a banquet. It is not your role to give an opinion on what may seem like wasteful behavior.

15. Chinese people do not have sweet cakes or ice cream as dessert. Some fruit will probably be served at the end, or after the meal in the sitting room.

16. Again, go slowly and follow the lead of others. It will take a while to master the protocols.

17. If you have food allergies or avoidances, make sure to discretely tell your host well beforehand.

FESTIVALS AND CELEBRATIONS

Overview

As Alessandro Falassi has stated, festivals are a sort of “time out of time” that provide a break with everyday routine and are rich in social meaning. In East Asia, the calendar year is marked by festivals of many kinds that take place for a variety of reasons. Many festivals were originally connected with ancient agricultural cycles of planting and harvest. Other festivals, such as those associated with seasonal grave-sweeping rites, are tied to cycles of life, death, and renewal. Many festivals are associated with Buddhism, Shintoism, and local belief traditions. In the past, most festivals in East Asia followed the lunar calendar, so their corresponding dates in the Western calendar vary from year to year. For example, the Chinese Spring Festival, the first day of the first month in the lunar calendar, usually falls sometime in January or February. Since the late 19th century, the Western Gregorian calendar has been introduced, and now some festivals, like New Year’s in Japan and Korea, fall on specific days each year.

New Year’s Festivals

Korea

The Korean year is marked by a complex series of festivals and associated rites. These begin with the New Year’s festival (Seollal), starting January 1st. The festival traditionally involved a ritual bath and the wearing of new clothes, rituals honoring the ancestors, offerings to various deities, visits and bowing to relatives, placing charms around the house for good luck in the coming year, preparing special foods, and playing a variety of games. Among the special foods are cakes made of rice and meat called tteokguk. To eat a bowl of tteokguk means to grow a year older. In many homes, when children bow to their elders, they receive a small amount of money. Gifts associated with longevity, such as ginseng, are presented to elders.

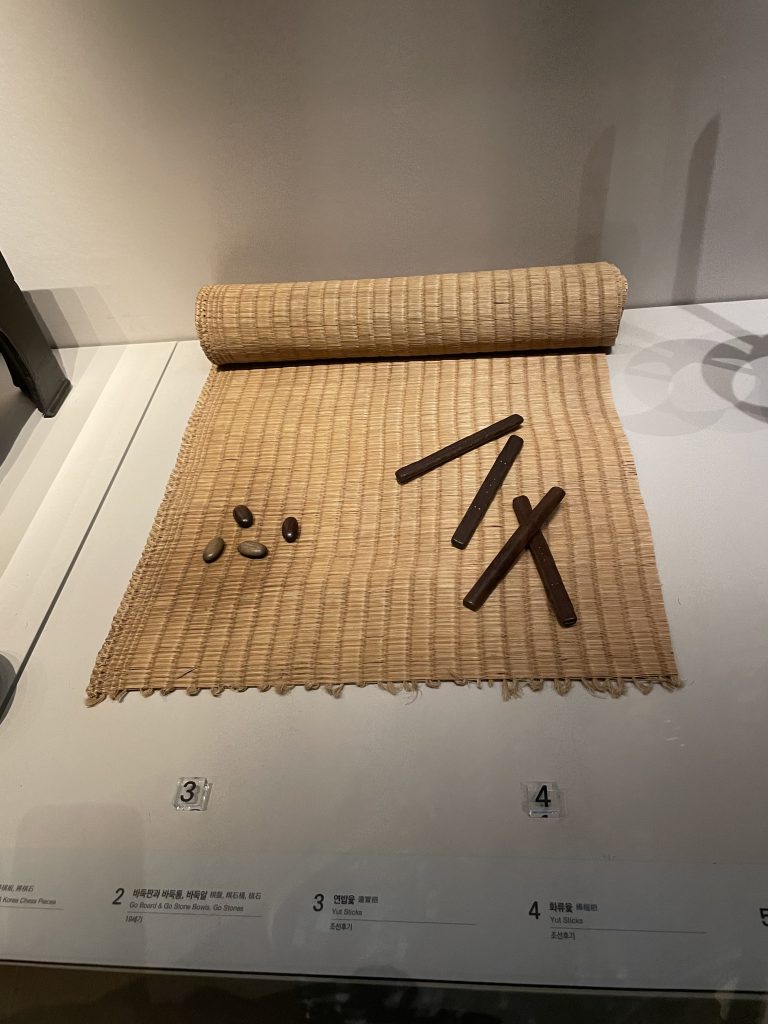

The yut game is among the most popular entertainment activities during New Year’s days. In the past yut was used to foretell a good or bad harvest in the coming year, but today it is practiced mostly as a game. Many of these customs are still followed today, though individual families have different ways of celebrating.

|

|

|

|

Japan

Since the Meiji Period in the late 19th century, Japan has celebrated New Year’s on January 1st of the Western calendar. The festival is a time for Japanese people to visit their relatives and get together with family members. They also go to the shrines or temples to pray for good luck. Hundreds of thousands of people will visit the most popular shrines and temples where large bells are rung when the turn of the new year comes. Japanese people also send New Year’s Day postcards to relatives, friends and co-workers, like the custom of sending holiday cards in the United States. Pocket money is given to children in small, decorated envelopes, called “pochibukuro,” similar to the Chinese “hong bao.”

|

|

Special dishes are served during New Year’s celebration. Toshikoshi soba, a type of thin buckwheat noodle, is made for New Year’s Eve. The word “toshikoshi” indicates the meaning of “getting into the new year.”Osechi ryori, which is made up of different types of dishes such as shrimp, seaweed, and fish, is made to celebrate the New Year. Each dish carries a special symbol—a wish or blessing for the New Year—such as joy, health, good luck, harvest, and so on.

A game called uta karuta is usually played on New Year’s Day. It is a traditional card game, based on Ogura Hyakunin Isshu, an anthology of one hundred tanka poems by one hundred different poets. In the game, people are given the first three lines of a poem and must find out the card with the last two lines. The player who gets rid of all the cards first is the winner.

|

|

China

Chinese New Year, or Spring Festival (Chun Jie), is the first day of the year in the lunar calendar and is the grandest of all Chinese celebrations. It lasts an entire two weeks. As in Korea and Japan, transportation all over China is overtaxed in the days leading up to the first days of the festival when everyone is trying to get home to meet family and friends. Although New Year’s is celebrated somewhat differently in different parts of China, in each case it is an opportunity for families to reconnect and indulge in massive amounts of special food in the form of lively feasts in homes and restaurants. Feasts and banquets may go on for several days, and related families usually take turns treating each other. However, the most important meal is the dinner on New Year’s Eve, when people send off the old year and welcome the new year. Favorite festival food is niangao. This specialty varies according to region and locality. In the Yangzi delta areas, it is similar to the Korean ttokkuk, a kind of “sticky” or glutinous rice cake that is cut in bite-sized pieces and served in a thin soup or fried. In many parts of China, it is usually sweet and made of flavored sticky rice paste filled with bean or date paste. No matter what kind it is, it is believed that eating niangao brings good luck and long life. Since the word for fish (yu) sounds the same to the word for “plenty” (though they are written in entirely different characters), it is customary in many areas to serve fish.

A common custom among Han Chinese is the giving of hongbao or “red packets.” Each child in the family hopes to receive the red packets containing small amounts of money, called yasuiqian, from older relatives and friends. Children may also receive new clothes on New Year’s. All the cooking must be done the day before the first day of the festival, and the home must be thoroughly cleaned and all the trash from the old year must be taken out before midnight of the first day. In many places, couplets expressing good wishes, written on red paper, are put on two sides of the main door. People also go to temples to light red candles or oil lamps and pray for good luck in the New Year. Although in many big cities it is forbidden to light firecrackers due to safety concerns, lighting firecrackers to get rid of back luck from the old year is still a common practice in the countryside. Additionally, many city dwellers go to suburban areas to light fireworks in order to take part in this tradition.

The final day of the festival, which is the fifteenth day of the first month in the lunar year, is called the “Lantern Festival” (Yuanxiao Jie). On this day, people carry around decorated paper lanterns in the evening, the lights adding to the festive atmosphere. Traditionally, people also write riddles, often in classical poetic style, on the lanterns. Those who do not carry lanterns can enjoy watching the lantern parades and guessing lantern riddles. On this day, tangyuan, or yuanxiao, kinds of sticky rice dumplings filled with sweet fillings such as white sugar and ground sesame and walnuts are served in thin soups.

|

|

Tangyuan can come in many forms. |

|

Ancestor Festivals

At some point during the year, festivals are held in conjunction with rituals that honor departed ancestors. During such rituals the graves of the departed are cared for and put in order (in rural areas this often involves trimming back vegetation that has accumulated during the year). In Japan the O-bon Festival, which originated from Buddhist beliefs, is held sometime in July and August (local dates vary). In the rural areas, family members gather (many returning “home” from the urban areas) to honor the souls of their ancestors. In some places, lanterns are hung, or rice straw is burned in the doorway to call home the souls of the dead. Families in both rural and urban areas prepare home altars and feasts in honor of the dead, share festival food, and visit shrines and temples. In many places a dance called bon-odori is performed in a public place, with people joining in at will.

In China, the Grave-sweeping Festival, or Qingming Jie, literally “Clear and Bright” festival, is held in early April, several weeks after New Year’s. Families go in a group to clean off the grave mounds and tombs of their ancestors. Traditionally, incense and candles are lit in front of the grave, and paper money and paper gifts called “joss paper” are burned for the departed. A ritual meal is shared with the souls of the deceased, followed by a big feast later in the day at home. In urban areas of mainland China, people are encouraged to offer flowers, usually chrysanthemums, in lieu of burning incense and paper money which can cause fires. In places like Hong Kong and Taiwan, there are special burners in the grave areas for people to burn offerings of paper money. Since the grave mounds and tombs are usually in the fields or hills in suburban areas, Qingming Festival is also a time for people to enjoy the Spring greenery. This activity is called taqing, or “treading on the greenery.”

|

|

In Korea, these activities take place during the Chuseok Festival described below. Family members (often only males) visit the ancestral graves and share stories of the past.

Harvest Festivals

Strongly linked to the agricultural past, harvest festivals are held locally across East Asia. The most famous harvest festival in China is the Mid-Autumn Festival (Zhongqiu Jie). Held on the fifteenth day of the eighth month of lunar calendar, which is usually in early or late September, the festival is a time when families gather in parks or on rooftops to view the full moon. In many universities, classmates hold all-night parties, chatting, singing, and snacking as the moon passes above. A special food eaten at this time is “moon cakes” (yuebing). These round cakes are filled with red bean paste, walnuts and sunflower seeds, dried fruits, and other delicious fillings. It is said that the Mongol rule of China ended after rebels hid secret messages about a rebellion inside the cakes. In recent years, moon cakes are wrapped in very fancy boxes and given, often with liquor or tea, as gifts among friends, co-workers, and relatives.

In Korea, the Chusok Festival is a time when families gather to celebrate the year’s bounty. Held on the 15th day of the 8th month of the lunar calendar (usually sometime in September on the solar calendar), it is a time when farmers made offerings to the gods and ancestors for a bountiful harvest and protection from harm. In the ancient history of the Three Kingdoms, the Samguk sagi, King Yuri of Silla staged a contest between two groups of local women, led by princesses. Each group competed in the art of weaving, and the losing group had to hold a feast as well as dance and sing for the winners. This is popularly thought to be the origin of the Chuseok Festival. Special foods eaten during Chuseok include a type of sticky rice cake steamed with pine needles called songpyeon. Made of fresh ingredients, the cakes are filled with sweet beans and formed into a half-moon shape (unlike the round Chinese ones). The half-moon shape represents hope for a fuller harvest in the coming year. The cakes are offered to the ancestors and then eaten by the living who participate in the ritual. In families with an expectant mother it is customary to hide a fresh pine needle inside a cake. If a pregnant woman bites the sharp end of the needle it is thought she will have a boy; if the blunt end is bitten, she will have a girl. Such customs add flavor to the family gatherings.

In Japan, every local area has its own harvest festivals that include parades, dancing, and feasting.

Other Festivals

China

Since China is a multiethnic country, many local festivals are held year-round. One festival commonly held among the Han people, especially in southern China, is an early summer festival called the Dragon Boat Festival (Duanwu Jie). It is celebrated on the 5th day of the 5th month of the lunar calendar. One of the legends about this festival is that it is held in honor of Qu Yuan, an ancient poet who lived in the State of Chu during the Warring States Period who committed suicide by jumping into a river. Traditionally, glutinous rice cakes wrapped in bamboo leaves, called zongzi, are thrown into the rivers on the festival so that the fish in the rivers will eat the cakes and not eat Qu Yuan. Today people do not throw zongzi into rivers anymore but eat the zongzi themselves.

In some communities, teams compete against each other while rowing long, narrow dragon boats. This activity originated from people searching for Qu Yuan’s body after his suicide. It is also said that on the 5th day of the 5th month, all the poisonous animals and bugs will become their most poisonous, and evil spirits will appear. Therefore, people carry small bags decorated with colorful silk thread and filled with fragrant herbal medicines. Some people hang special herbs by their main door to exorcise the evil spirits. After the herbs dry, they are boiled with water and used as a bath to cure skin disease. In the Yangzi River area, there is also the tradition of drinking a type of herbal wine called yellow wine (huangjiu).

|

|

Many ethnic minority groups in southwest China celebrate midsummer festivals, like the Torch Festival of the Yi ethnic group where local people dress up in their finest traditional clothing and hold parades and fashion shows. The torch celebrations held among the Sani people in the Stone Forest of Yunnan province involve tens of thousands of revelers who watch bullfighting contests, high-tech and traditional song and dance performances, fireworks displays, fashion shows. They also participate in huge circle dances and torch parades.

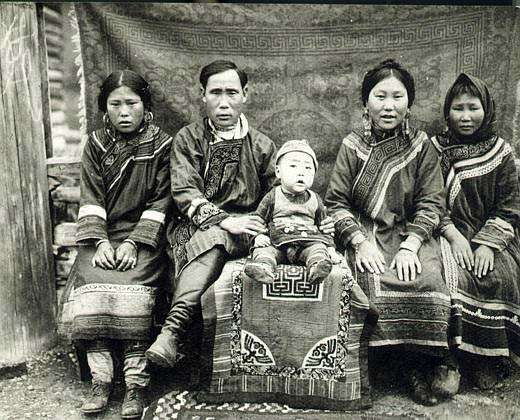

Singing and courting festivals are held in Miao, Dong, and Zhuang areas in Guizhou and Guangxi. The Dai ethnic group in southern Yunnan province has the Water Splashing Festival in which everyone on the street douses each other with basins of freshwater. Horseracing festivals are held among Tibetans and other ethnic groups in western China. People will gather for several days to race horses, camp out, and feast in the open air. The Nadaam Fair held in Inner Mongolia, is a traditional summer festival of the Mongols which features horse racing and wrestling as well as opportunities to socialize and trade.

Korea

Many festivals and observances occur on the lunar calendar in Korea. Besides the ones already mentioned is a traditional festival called “Foundation Day” which occurs on October 3. This festival honors Dangun, the mythical founder of Korean culture. Feasts are also held on the Winter and Spring solstices. According to tradition, on December 22nd (using the modern calendar) everyone becomes one year older, and a special porridge made of red beans and glutinous rice is prepared and offered to household gods for protection. There are also many local festivals in South Korea. In some cases, farmers make gigantic floats of wood and rope used in mock battles against floats of other villages. In other places tug of war games are played with elaborately woven ropes. Although many customs have fallen by the wayside as the rural areas have modernized, in some places customs stay alive due to local festivals that emphasize aspects of Korean heritage. Many of these festival customs are also represented in exhibits in the National Folk Museum in Seoul. Some local festivals have taken on a modern, sometimes commercial, twist. Each summer in the mountainous city of Geumsan, for example, the highly commercialized Ginseng Festival is held. Local farmers and businessmen promote the benefits of the medicinal root. Activities include observances to the local gods, song and dance performances, beauty contests, games, fireworks, parades, and displays of medicines and tonics made from ginseng.

|

|

Japan

Several other national festivals and hundreds of local ones are held in Japan each year. One popular festival is called “Doll’s Day” (or “Girl’s Day”; Hinamatsuri in Japanese), held on March 3rd. During this festival, dolls representing the emperor, empress, and other figures are displayed for good luck and girls hold special parties among themselves. An occasion for boys is held a few weeks later the fifth day of the fifth lunar month. Households with young boys display colorful streamers in the shape of a fish called a carp on housefronts.

For over a thousand years the Gion Festival has been held each July in the ancient city of Kyoto. Originally held to secure the populous from disastrous epidemic it is marked by amazing parades of floats and by people in ancient dress, some dressed as warriors on horseback wearing swords and bows and arrows. In some locales, fertility festivals are still held, such as the internationally famous—and highly marketed—Kanamara Matsuri Festival in Kawasaki. The event draws hundreds of thousands of people from all walks of life. It is highlighted by observances at shrines where women worship in the hope of becoming pregnant. It is also famous for its parades, which feature gigantic wooden renditions of male genitalia that have long been a part of folk belief in Japan. A special museum in Takayama is devoted to the display of giant floats of this type that are maintained by local communities and wheeled through the streets during the festivals.

|

|

Consumer marketing is directly responsible for a unique celebration of the Japanese version of Valentine’s Day on February 14th. It is now customary for young women to give gifts of chocolate called giri-choco (literally, “chocolates given out of a sense of obligation”) to male bosses and coworkers. Special male friends receive presents of chocolate, along with other gifts. To equal things out, men give gifts to their significant others at a festival held on March 14th called White Day.

COSTUME

Overview

East Asia has rich traditions of costume and adornment, ranging from traditional clothing of the ruling elites and the common folk to the creative garb of the contemporary youth cultures and the pursuit of urban high fashion. Certain patterns, styles, techniques, and materials were shared over many centuries, along with unique local innovations. Many basic styles and manufacturing technologies seem to have originated on the continent and later spread to peninsular Korea and the islands of Japan. It is interesting that the traditional clothing of Korea, Japan, and some of the ethnic minority groups in China retain aspects of styles that have long died out in mainstream Han culture in China. This is especially true of the fashions of the Chinese Tang dynasty (618-906 CE). The Han Chinese, however, were sometimes subject to foreign influences themselves. During the Qing dynasty, for example, the Manchu rulers forced their subjects to alter the styles of their hair and clothing. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Western styles of clothing began to be adopted in East Asia. During the Meiji Restoration in Japan, Western-style suits, military uniforms, school clothes, and even ladies’ hoop skirts were introduced to a portion of the urban population during this era of great social change. In the early decades of the People’s Republic of China (and today in North Korea) military-style or very plain clothing became daily wear for hundreds of millions of people. Today, the youth cultures in Japan, Korea, and more recently China, exhibit a wildly creative range of popular trends, consumer fast fashion, costume, occasion wear and fantasy clothing, influenced by—and influencing—the global fashion industry. Moreover, as the quote above stresses, traditional clothing is still of importance for the successful symbolic “marketing” of nations pushing their own interests.

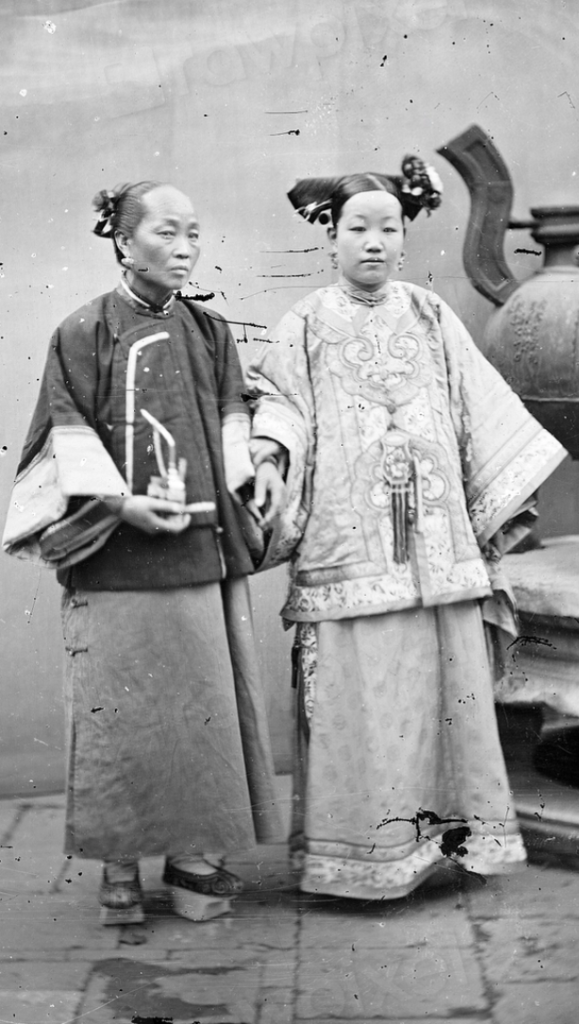

Korea

The most important word in the history of Korean costume is hanbok. The word means “Korean clothing” and can be used to describe both male and female traditional garb. Today hanbok is worn only by the old, or during festivals, weddings, and other special occasions. However, images of hanbok are seen everywhere in South Korea and have become a symbol of traditional culture in general. Clothing stores offer a wide range of costumes at different price points, with the most expensive handmade hanbok costing many thousands of dollars. Traditional hanbok are made of cotton, hemp, ramie (a hemp-like plant), and silk. Today cheaper hanbok are made of synthetic materials.

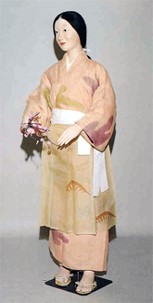

According to Korean costume expert Prof. Chang In-woo of Incheon University, women’s hanbok developed over time. Today the traditional garment has three major parts: a short, tight-fitting blouse called a jeogori, a full, floor-length skirt called a chima, and a long sash looped under the arms and across the breast called a goreum. Cotton pantaloons (baji) are worn beneath the skirt, as well as quilted white socks known as beoseon. Cloth shoes with toes that curve up were once commonly worn outside the home, though beoseon were worn on the lacquered paper floors inside the home. In early times the blouse was quite long, though by the 18th and early 19th centuries the blouse was short and the skirt reached to the breast line. When Korean young women began attending Western-style schools in the early 20th century, their blouses again became longer and the skirts shorter and less full.

Accessories for traditional hanbok included small ornate pendants called norigae, attached to the blouse tie; a small, decorated knife (called a “chastity protector” or eunjangdo) worn on the blouse tie or sash of the skirt; and a long elaborately decorated hairpin worn by married women. During the Joseon (Joseon) period it became fashionable to wear huge, braided hairdos reinforced with extensions purchased from poor lower-class women who sold their hair. In some instances, young brides could barely hold up their heads. Outside the home women wore cloaks that covered their heads. Fashions of the courtesans known as kisaeng, who were not bound by the strictures of Neo-Confucian morality, were sometimes extravagant and influenced the dress of more conservative women as time wore on.

|

|

|

|

Men’s clothing traditionally consisted of a pair of pants (baji) and a shirt (jeogori). Upper-class scholars and officials wore special hats made of woven horsehair and long, full jackets. Wedding clothing for women in richer families include red silk gowns embroidered with flowers and other fertility symbols. The auspicious colors of red, blue, green, yellow, and white decorate many women’s hanbok. The most elaborate traditional clothes, of course, were reserved for the ruling family.

|

|

After the Korean War in the 1950s, Western-style fashions caught on rapidly throughout the population in South Korea. Although clothing remains conservative in North Korea, designer brands, creative pop and high fashion are the rage in the South due to democratic liberalization and a high-energy economy. In some cases, traditional patterns and styles are worked into contemporary fashion creations.

|

|

|

Some contemporary styles are influenced by tradition, whether traditional Hanbok (left and right) or Western styles from the 1920s (center). [Click images to zoom] |

||

Japan

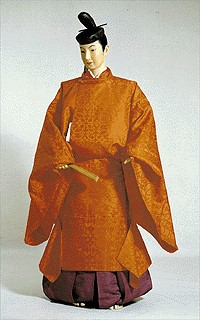

An ancient Japanese creation myth tells of how the Sun Goddess Amaterasu was weaving silk when insulted by her brother, causing her to withdraw into a cave until eventually coaxed out by the dancing of other gods. Thus, the idea of weaving, textiles, and clothing is deeply embedded in Japanese culture, exemplified by great skill in design, execution, and production over the centuries. Over time Japanese clothing was influenced by continental contacts, including the historic introduction of silk from China as early as 180 CE. By the time of increased Chinese contact in the 6th-7th centuries, the clothing of the upper-classes was bulky and many-layered. Though over time garments became smaller in dimension they retained simple, but aesthetically pleasing forms. Cloth dyeing was especially important in clothing production throughout the Edo period as the middle class expanded in size and demand for clothing increased. Dyers excelled at the art to produce an amazing array of colorful, exciting designs, along with the family crests of upper-class patrons which were dyed into the upper portions of the clothes made for them.

|

|

Influence from Chinese costume styles can still be seen in the clothing of royal court official and wife in Nara period. |

Replica costumes of upper-class women (left) and lower-class women (right) of the Heian period. |

|

|

|

|

Replica costumes of upper-class males (left) and lower-class males (right) of the Heian period. |

The most famous word in the history of Japanese clothing is kimono. The word means “thing that is worn” and refers to female and male clothing. Kimono styles still retain certain influences from Tang or pre-Tang China, though they have evolved on their own path over the centuries. The basic form of kimono, once the typical dress of the middle and upper classes, is the basic robe itself, and a large sash called an obi. White socks (tabi) that are made with a split between the big toe and second toe are normally worn with clogs called geta. Today most Japanese women seldom wear kimono and many younger women do not even own one. This is even more true for men. Occasions for wearing kimono today are festivals, certain formal events such as a tea ritual or weddings, traditional performances, and sports (for example the garments worn by officials in sumo wrestling matches), and also instances of personal choice.

|

|

Since the 1950s Japan has risen as a major force in the worlds of fashion and pop culture costume. Ranging from the sedate and understated to the magically fantastic and avant-garde, modern Japanese fashion has, since the 1980s, tended to follow trends set by young unmarried office women, often living at home, who have the expendable income to spend on designer clothing, handbags, and other accessories. International destinations such as Honolulu, Hawaii; Bangkok, Thailand; and Australia cater to this market by supplying blocks of brand name stores. The Harajuku district in Tokyo is sometimes described as the “epicenter” of Japanese youth culture and can be a sensory-overloading demimonde where young people from the suburbs deck themselves out and come to stock up on products to fuel their creation of cosplay (costume play) characters and other sub-culture trends.

|

|

China

Han and Manchu Clothing

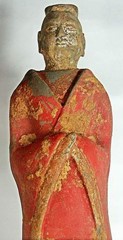

|

|

|

Burial practices that have preserved clothing from over two thousand years ago and a rich tradition of painting and sculpture (as in Japan and Korea) have allowed specialists to chart the changes in clothing styles in China since the earliest dynasties. Hanfu, literally “Han clothing”, refers to the traditional costumes of the Han Chinese ethnic group as they evolved for more than 3,000 years up to the 17th century. Starting from as early as the Zhou dynasty, dress codes were established and enforced by rulers. Various styles of Hanfu were assigned according to a person’s social status, setting a standardized sartorial hierarchy in society. Basic patterns of Hanfu were formed in antiquity and modified over time. Hanfu significantly influenced the traditional clothing styles of many other Asian countries, including both the Korean hanbok and Japanese kimono, although both developed into styles quite distinct from Hanfu. Influences also entered China from the Middle East, Central Asia, India, Southeast Asia, and possibly ancient central Europe. Weaving and textile production were important aspects of early technology, and evidence of spinning and weaving goes back to Neolithic times.

|

The male and female characters in this Chinese TV costume drama set in the Han dynasty are wearing quju, a type of Han clothing that wraps around the body and is tied by a silk belt at waist level. |

One of the most exciting times in the history of Han Chinese garments was the Tang dynasty, when silk was the major trade item, enjoyed near and far. Although cotton (from India) was still little known in China, hemp, ramie, and linen already had long histories of use. Felt (often used for hats) seems to have been introduced from Central Asia. As with Zhou and Han dynasty rulers, Tang rulers liked large robes with huge sleeves that opened down the front. Although the various grades of officials and their wives all wore clothing colored according to rank, the common folk were only allowed to wear white garments. Women of rank and entertainers indulged in various sorts of makeup that included white or yellow powder, vermilion rouge, painted (plucked) eyebrows, and small colored patterns placed on the forehead and temples. Hairstyles were often elaborate. In some cases, dresses showed cleavage—unthinkable in later dynasties.

|

|

Costume, hairstyle, and makeup of women of high rank in Tang dynasty. |

|

|

|

Costume, hairstyle, and makeup of ladies-in-waiting of different ranks in Tang dynasty. |

|

|

(Photos by unknown photographers) |

|

|

|

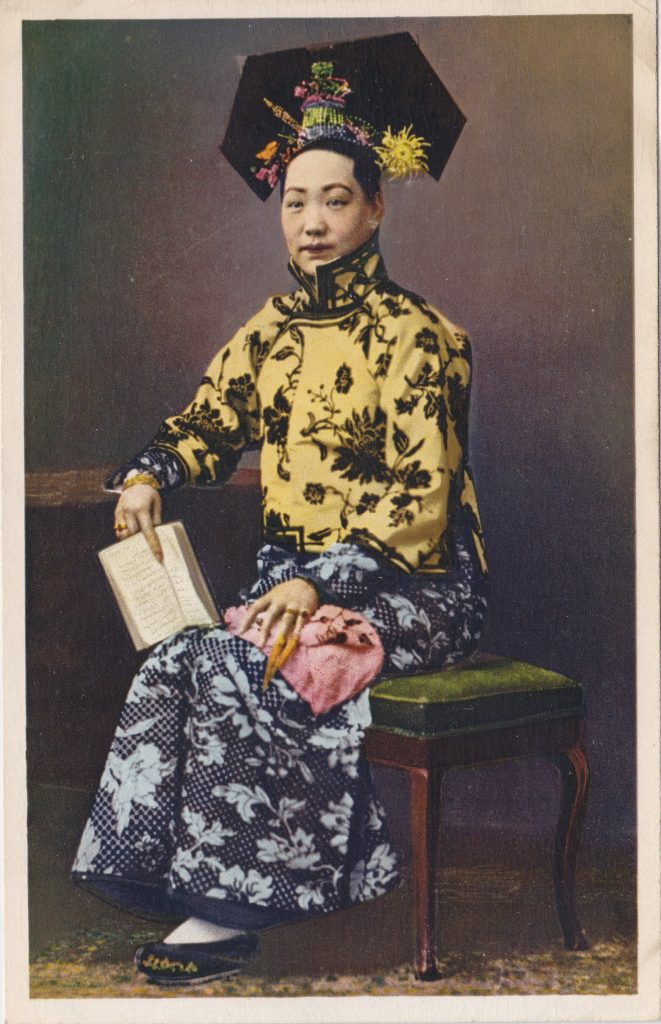

During the Qing dynasty, Han people were forced by the ruling Manchus to adopt a Manchu hairstyle (the long pigtail or queue for men) and Manchu clothing. Of particular importance was a type of side-fastening garment with a high collar and tight sleeves derived from the costumes of mounted steppe warriors. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the women’s version of this style evolved into the still-popular dress known as a qipao (or cheongsam) with its side slitted skirt. Figure-hugging styles of the dress became popular in Shanghai in the 1930s. Versions with the highest slits up the sides were associated with entertainers of various sorts, with modestly slit dresses regarded as acceptable formal wear.

|

|

Manchu official’s casual clothing (left) and official’s formal costume (right). |

|

|

|

|

The qipao was essentially banned during the Cultural Revolution when the Chinese developed a kind of “revolutionary” “grunge look.” But immigrants from Shanghai to Hong Kong during the civil war brought the fashion to Hong Kong. In recent decades there has been a Shanghainese qipao come back in Mainland China, especially among staff of higher-end restaurants in China. Many Chinese people also wear qipao for New Year, weddings, parties, and other social events. Gradually, qipao has been regarded and presented as Chinese national costume internationally, and in the United States qipao fashion shows have become a “thing” in some Chinese folk-dance clubs.

|

|