7 Module 6: Art in East Asia

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

OUTLINE

INTRODUCTION

The cultures of East Asia have bequeathed to the world an amazing and varied legacy of art that ranges from classical fine art, to popular, decorative, folk, and modern art. This unit outlines the mediums, modes, and intellectual and spiritual expressiveness of major types of art in East Asia. Since calligraphy, landscape painting, and ceramics are so central in East Asian art, stress will be given to these three categories. Thus, you will learn some of the basic styles of calligraphy, “how to read” a traditional painting, and learn to identify a number of styles of ceramics from different ages of history. These skills are aesthetically rewarding and are regarded as indices of “self-cultivation” by many in East Asia.

SOME OBSERVATIONS ON ART IN EAST ASIA

In East Asia the arts, like elements of worldview, often have a strong eclectic and syncretic nature. Many “genres” and/or mediums of expression may interact in one artistic phenomenon. In many cases, the natural surroundings may enhance the work of art, and certainly contribute to ideas of how it is to be placed. A landscape painting, for instance, may include the painting itself, calligraphy written directly on the painting—usually a poem (which can be read aloud, giving the painting an auditory dimension)—and a red name stamp, representing the art of seal cutting. Where and how the painting is displayed will depend on how it contributes to the overall setting of a room. Traditionally, placement of a work of art is done in accord to the principles of harmonious balance between nature and humankind.

Gardens as “Multi-media” Experiences

East Asian gardens may be the best example of the tendency to combine mediums for the ultimate aesthetic experience. A single garden may include artistically laid rockery, weirdly-shaped rocks, marble, plants (bamboo, pine, maple, plum, lotus, chrysanthemums, moss, etc.), tiny bonsai trees, pavilions made of wood (painted or left natural) and stone, running water and pools, archways, gates, steps, pathways, carefully placed paintings and ceramics, poems or characters carved here and there, and other features that blend together as a whole, yet allow for constant surprises at every turn. In some cases musical instruments may be played in the gardens to add another dimension. Gardens vary in set-up and “feel”—many of the most famous ones in Japan were designed by Zen masters.

|

|

|

|

A room or niche in a home will have often have a painting, ceramic, or other work of art on display. Officials, literati, and samurai (in Japan) loved collecting and displaying antique art and very “modern” style display racks were in wide use in China by the Song period. Major cities in East Asia all have large antique markets where many people go to look at or acquire aesthetically pleasing objects that link them to persons and tastes of ages long past. In many places, there are parts of town selling wares by living artists who carry on the ancient arts. In Japan and Korea such people are considered as “living national treasures.”

Variation by Cultural Area

All three cultural regions share many common traits, though there is substantial variation locally. While many artists in both Korea and Japan mastered Chinese styles, there are many instances in which uniquely Korean or Japanese styles were created. This is especially true in ceramic and decorative art, though many instances could be cited in painting and sculpture, as well. Worldview beliefs, especially Buddhism and Confucianism, influenced the arts in all three cultural areas.

|

|

Who Made the Art?

Another interesting feature of art in East Asia is who created the art. In all of the cultures, art was produced by a variety of people. In some cases artworks, especially painting and sculpture were created under the patronage of the ruling class. In Song dynasty China, for instance, there was a royal painting academy under imperial sponsorship. Many artworks, especially calligraphy and painting, were made by non-professional artists, that included scholar-officials (for example, the yangban in the Joseon dynasty Korea), monks, upper-class women, and in Japan, samurai. Many decorative works, including ceramics; carvings in jade, nephrite, and ivory; cloisonné; and lacquerware, were produced by craftsmen-artists in small shops, larger kiln or craft centers, or monasteries. Although in some cases the identities of the organizations survive, the names of individual artists are seldom known.

Buddhist Art

Influences from Mahayana Buddhist art in India spread with the teaching of Buddha on the Silk Road and through some avenues farther south in China. As the centuries passed, recognizable differences in Buddhist art of the different parts of China, Korea, and Japan developed. Of particular interest is the depiction of various representations of Buddha, bodhisattvas, and other figures at different periods in the different cultural areas.

One example is that of the bodhisattva Guan Yin (Avalokitesvara), whose images begin as male in India, but are eventually transformed into a female in China. A famous wooden Kannon (Guan Yin), in the treasure hoard at the Horyuji Temple complex near Nara, Japan, seems to exhibit traits of both sexes. Distinctly Korean images of Buddha exist as small bronze figures of a very thin Buddha with a crossed leg—similar ones found in Japan may have ultimately been of Korean origin.

Asia, including Taiwan and Japan. The huge bronze Buddha at the Todaiji temple in Nara is the largest metal Buddha in East Asia, housed in the largest wooden structure on earth. One of the most magnificent statues of Buddha is the Seokguram Buddha near Gyeongju in South Korea, hidden for over one thousand years in a specially constructed stone vault on a mountainside. The Haeinsa Temple complex in South Korea has wonderful Buddhist murals, statues, musical instruments, and other items, as well as the 80,000 printing blocks of the Tripitaka Koreana.

The largest Buddha carving in China is at Leshan in Sichuan province, carved into the cliffs of a tributary of the Yangzi River. The Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang house some of the most fabulous Buddhist statues, carved from natural stone in the rock cliffs in eastern China. In the Dunhuang Grottoes in Gansu province, giant statues of Buddhas and painted frescoes from several hundred years of occupancy are found in over 400 caves along a small river that meanders through the harsh deserts and sand dunes of northwest China. Styles of Theravada Buddhist sculpture, paintings, and temple architecture can be found in the Dai ethnic group regions in Xishuangbanna, in southern Yunnan province.

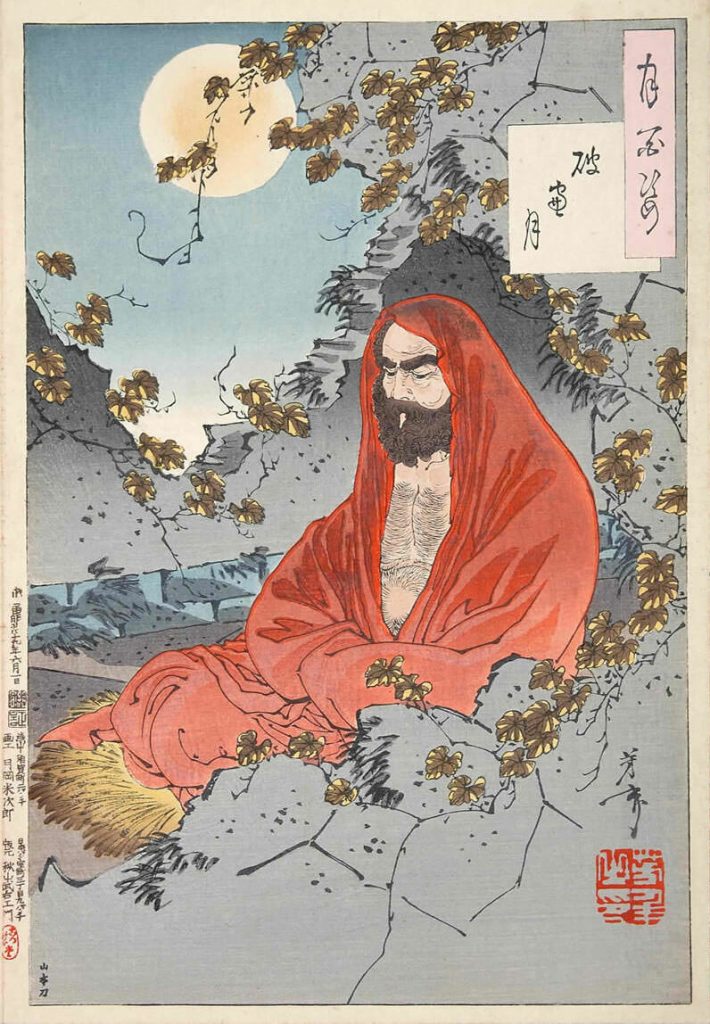

In Japan, Zen Buddhism had a profound effect on Japanese society between the 13th and 16th centuries. Although samurai culture demanded skill in warfare, the martial arts were refined under the influence of Zen. Monks were responsible for introducing the teachings of the 6th century Indian monk Bodhidharma (Daruma in Japanese) from China and developing Zen aesthetics through art and meditative practice that included landscape painting, ceramics, and the building and maintenance of gardens. After 1600, Zen lost its patronage of the samurai government, but Zen influences spread through society, in part by efforts of artist monks. Paintings reflecting Zen concepts, ceramics, architecture, and fleeting arts such as flower arrangement, all were influenced by a contemplative Zen aesthetic, which found expression in activities such as the tea ceremony and visits to gardens like the Ryo’anji Temple in Kyoto.

|

|

In Nikko, Japan, the grand Toshogu Shrine that houses Tokugawa Ieyasu’s mausoleum was constructed using both Shinto and Buddhist styles. |

|

Among the richest traditions of Buddhist art developed in Tibet under Indian, Central Asian, Chinese, and native influences of Bon shamanism. Buddhist monks (which at times included a large percentage of the male population) created paintings called thangka which represent Buddhist visions of the universe and states of Buddha and other figures from Buddhist lore. Vast temple complexes were adorned with huge murals relating Buddhist stories. Intricate sand paintings that are destroyed on completion and intricate butter statues demonstrate the illusion of permanency. A great amount of Tibetan art was taken by outsiders in the early 20th century or destroyed during unrest in the late 1950s and again in the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Since the 1980s, some temples have been rebuilt or restored and various art forms are again being produced. In 2004, a fabulous exhibit of Tibetan Buddhist art was held at the Columbus Museum of Art. Co-curated by John Huntington of OSU and Dina Bangdel, the exhibit represented Buddhist art as a concrete realization of the steps of Buddha’s enlightenment experience. The Cleveland Museum of Art has several fine examples of Tibetan art.

|

|

Interactions between East and West

Although China was a major creative force in the art of East Asia, Chinese culture was influenced considerably at different times by the cultures of India, Central Asia, and even the Mediterranean. Influences of Greco-Roman architecture and sculpture, especially styles of columns and the drapery and representation of human figures in some Buddhist statues, were incorporated into traditions of Buddhist art in India and made their way across the Silk Road as far as Japan. The Western painting techniques of perspective, portraiture, and full canvas painting, were introduced (with limited influence) into China and Korea by Jesuits beginning in the Ming dynasty. By the late 18th century, some Japanese artists were experimenting with European landscape techniques and oil paints. Influences went the other way, as well, sometimes through complicated channels. For instance, the Dutch introduced the secrets of porcelain (favored in part because it held alcohol well) into Europe from Japan by the 17th century, stimulating the blue and white ware industries in Delft (located in Holland) and other cities. The blue and white pattern was actually Ming dynasty Chinese, though the cobalt blue pigment was Persian in origin. To complicate the story, the Japanese had earlier gotten porcelain secrets from a whole village of Korean potters kidnapped in the invasions of the late 16th century.

In the 18th century an interest in things Chinese, known as “Chinoiserie,” swept Europe and influenced garden design, fashion (such as French women with parasols and folding fans, which were actually a Japanese invention), and an interest in East Asian art. Commodore Perry’s opening of Japan in the 1850s stimulated a similar interest in things Japanese called “Japonisme.” This wave of interest began in Europe in the 1860s and stimulated Impressionist artists like Vincent Van Gogh. An American version of Japonisme crested in the 1880s and 1890s and continued into the 1920s. The fever for things Japanese included exhibitions of and publications on Japanese art. Several American artists, some who spent time in Japan, employed Japanese techniques, often producing creations on Japanese themes. These artists of the late 1890s and early 20th century included painters John La Farge and Robert Blum; woodblock artists Helen Hyde and Bertha Lum; and architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Edna Boies Hopkins, who had a connection with The Ohio State University, also created woodblock prints.

|

|

Edna Boies Hopkins graduated from the Art Academy of Cincinnati in 1899 and married John Hopkins in 1904. The couple took a world tour, spending part of it in Japan. John was later head of the Department of Fine Arts at The Ohio State University. Edna, who wore pants and dyed her hair red, lived a rather flamboyant life in New York. She held exhibitions of her prints in Paris, including at the Louvre.

CLASSIC TRADITIONAL ARTS

Appreciating Calligraphy

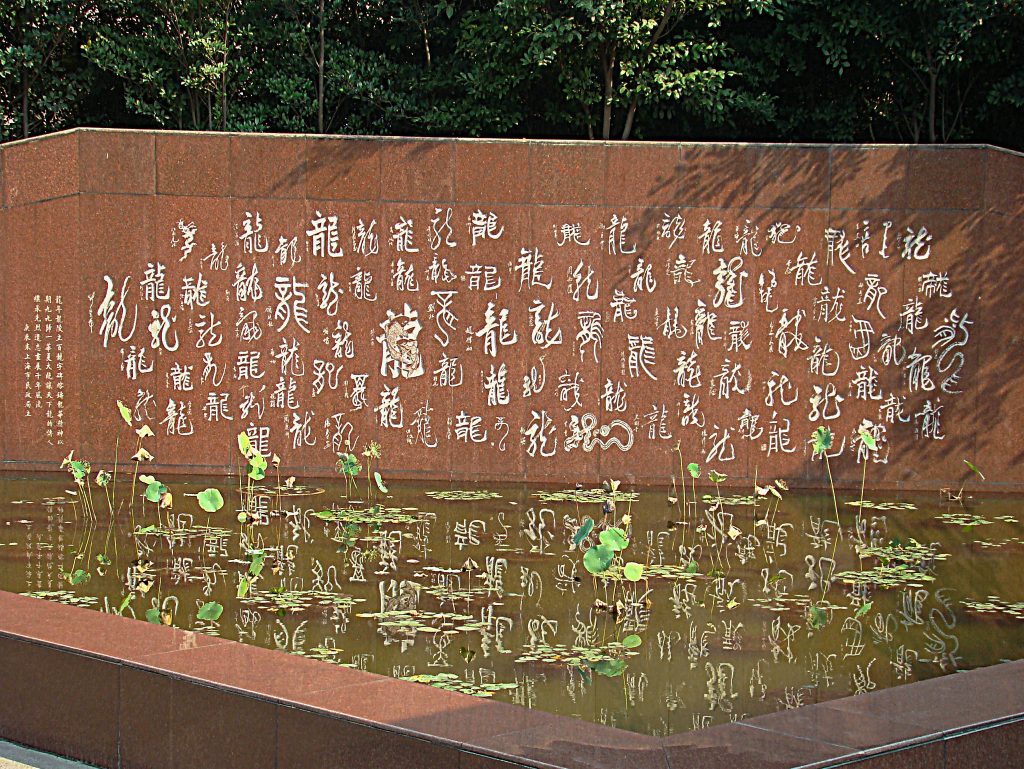

Calligraphy is the art of writing Chinese characters with a brush. It has traditionally been considered the most respected art form, where individual works of calligraphy have been highly sought after by Chinese collectors for centuries. Valued for its beauty and execution, good calligraphy directly communicates life force (“qi”) in every stroke and gives moral insight into the heart/mind of the artist. Excellent calligraphy was the mark of learning and cultivation among scholar-officials in East Asia, as well as learned samurai, artist-monks, and cultivated women. Some Chinese emperors, such as Song Huizong, of the Song dynasty, are remembered as much for their calligraphy as their ability to rule.

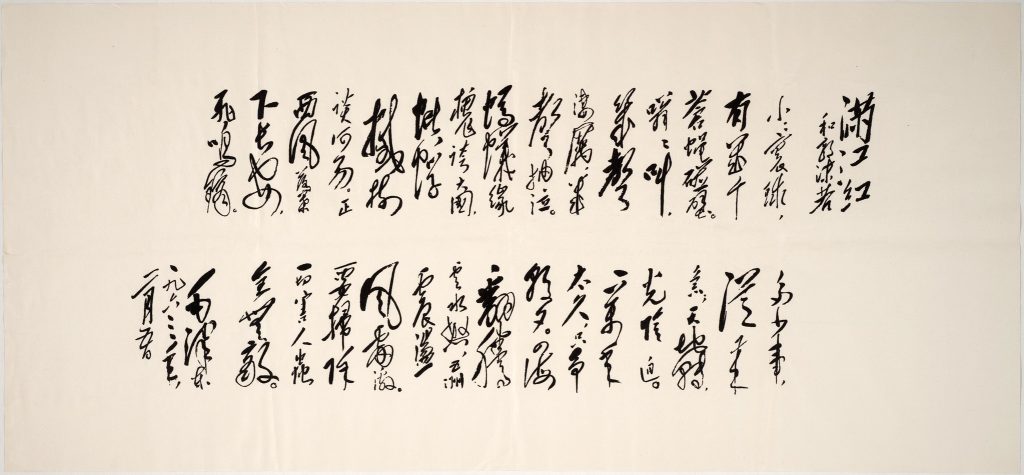

In more recent times, the calligraphy of the late Chairman Mao Zedong has been recognized in the PRC for its excellence. Calligraphy was the mark of a person’s cultivation and embodied both personality and moral integrity. Each stroke is carefully scrutinized and once executed cannot be “fixed up” by going back over a line. Since scholars were often called upon to write poems or dedications in public, it was essential to have excellent calligraphy in order to avoid losing face. In some cases, a few calligraphers ability took on an almost mythical quality. The Korean scholar Kim Gu (1488-1534) is said to have produced such powerful writing that the characters literally seemed alive. Towards the end of his life he wrote a large version of the word “to fly” and displayed it on his wall. Sometime later the paper began to mysteriously float around the room before disappearing. It was later discovered that he had died at the same moment. (Yoo 1988: 117)

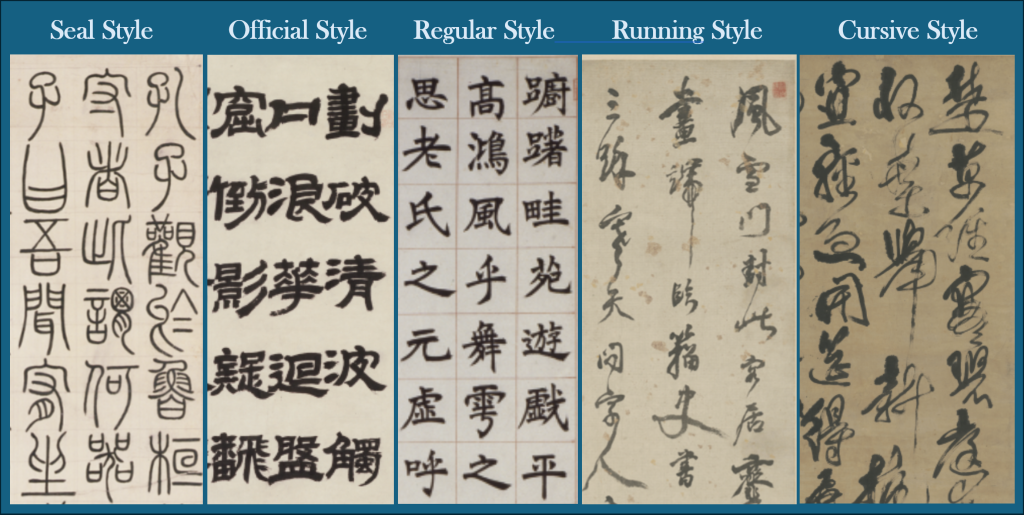

Calligraphy is still practiced by many people today, often using models that date back to the 4th century CE. Five basic styles, with many variations are followed. The very early styles are still appreciated and produced as decorative art and often used in making name seals. More “regular” styles were used in official and everyday writing (and became the basis for printed characters), while the more cursive styles (difficult to read, though extremely beautiful) border on abstract art. Bookstores and special calligraphy supply shops offer copybooks, models, brushes, ink stones and other equipment that is nearly identical to that used in Chinese painting.

“Seal Style” (Zhuan shu): earliest forms; including the oracle bone styles; still used on name seals

“Official Style” (Li shu): created by Cheng Miao in the Qin dynasty (246-207 BCE); used widely in documents during the Han dynasty and thereafter

“Regular Style” (Kai shu): arose in the Han dynasty and became popular in the Tang dynasty; practitioners include Wang Xizhi (Jin dynasty), regarded as the greatest Chinese calligrapher

“Running Style” (Xing shu): dates form the later Han dynasty; is a form of cursive writing; an example is Emperor Song Huizong’s “Slender Gold” style

“Cursive Style” (Cao shu): dates from the Han dynasty; originally a quickly written “rough” style of writing, later appreciated much like abstract art in which the characters often ran into each other as they flowed across the page

How to Read an East Asian Painting

Few examples of painting exist before the Han dynasty in China, though images inscribed in stone (which may have been painted), colorful weaving, and tomb murals that depict humans and supernatural beings suggest what might have been. Paintings on tomb walls date from the Han period in both China and Korea, giving insight into daily life of the times, and sometimes incorporating images of nature.

Buddhist art dating from the 4th-century CE covers the walls in the Mogao caves at Dunhuang in Gansu province, China. The earliest true landscape paintings date from the Six Dynasties period between the fall of the Han dynasty and the Tang. In the Tang, portraits of human activity were popular.

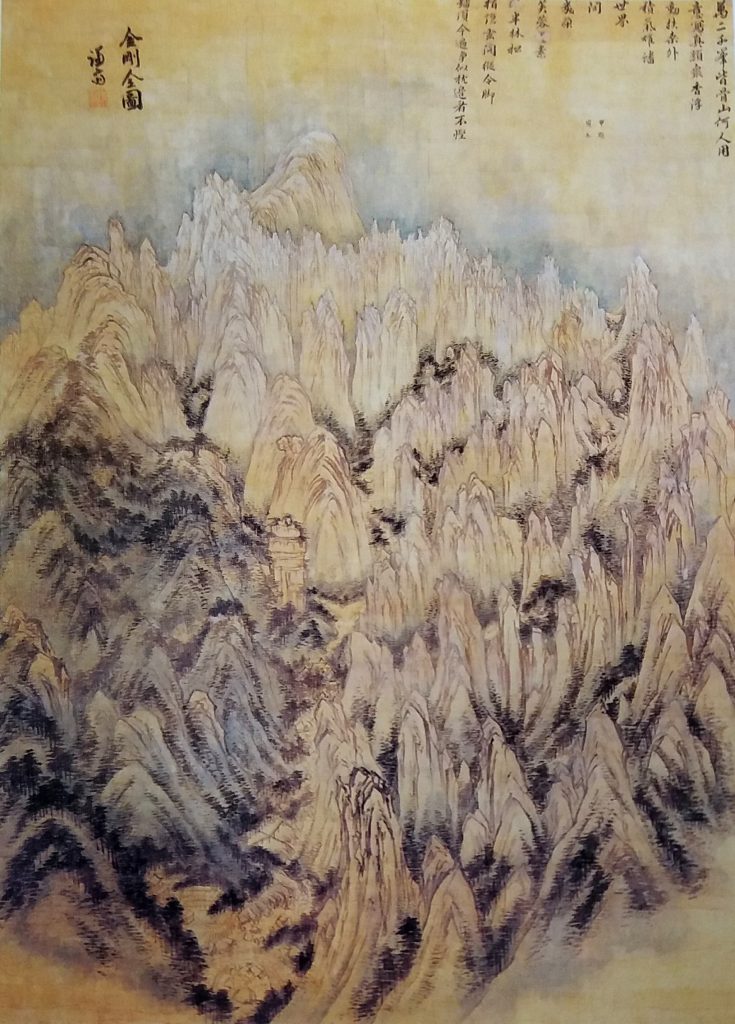

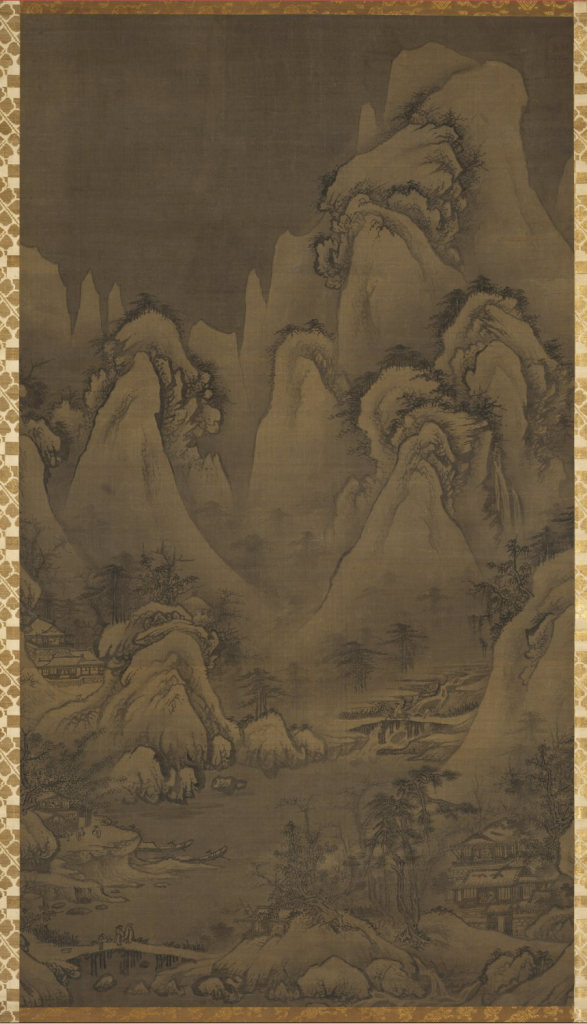

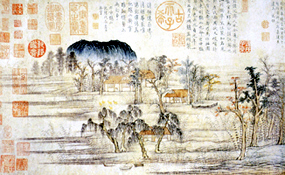

Tang landscape paintings, typically executed in blues and greens, often featured mountain scenes with minimal human presence. Landscape painting reached new peaks in the 11th century in the Northern Song dynasty. It was during this period that it became common to write poems directly onto paintings, thus combining the arts of calligraphy, poetry, and painting. The towering landscapes of the Northern Song, eventually gave way to more distant landscapes in the Southern Song, in which large blank white spaces (negative space, often representing mist or clouds) were prominent, contrasting with starkly painted mountains and trees executed in black ink and lighter grey washes. Over time a diversity of landscape styles evolved, and continue to evolve today. Landscape paintings in Chinese styles were transmitted to Korea and Japan where local characteristics developed. During the Joseon dynasty, many Korean scholar officials (the yangban) spent their leisure hours in painting landscapes, some with unique rockery that reflected the geographical nature of the peninsula. In Japan, some styles of landscape painting acquired fantastic color patterns, while others were strongly influenced by Zen.

This 15th century Korean landscape features many aspects of the landscape genre, According to the catalog listing, “This wintry vista is a vivid example of idealistic monumental painting: the strong contrasts of ink washes and contouring brush lines; the bold outlining of rock shapes and tree trunks; and the many short, twisting brushstrokes that build up the surfaces of the rocks. Much of the painting’s appeal can be attributed to the dynamic lines and contrasting tonal patterns that lead the viewer’s eye from the lower foreground toward the cold mountain peaks in the distance. In the corner is a seal that reads “Yeoseol,” meaning “Snow-Like.”” (quotation from John L. Severence fund, Cleveland Museum of Art)

|

|

|

Besides the more contemplative styles, other Japanese landscapes are vibrant in color and activity. This is illustrated by a huge painting executed on folding screens produced in the early Edo period around 1611. Attributed to Tosa Mitsuyoshi, the work depicts the Battle of Sekigahara. The screen depicts the warring armies of Tokugawa Ieyasu and his rival, Commissioner Mitsunari. More than 2,000 figures (out of an estimated 160,000 actual participants) are illustrated on the screen, which includes colorful banners, bright green hills, and shimmering mists made with gold leaf.

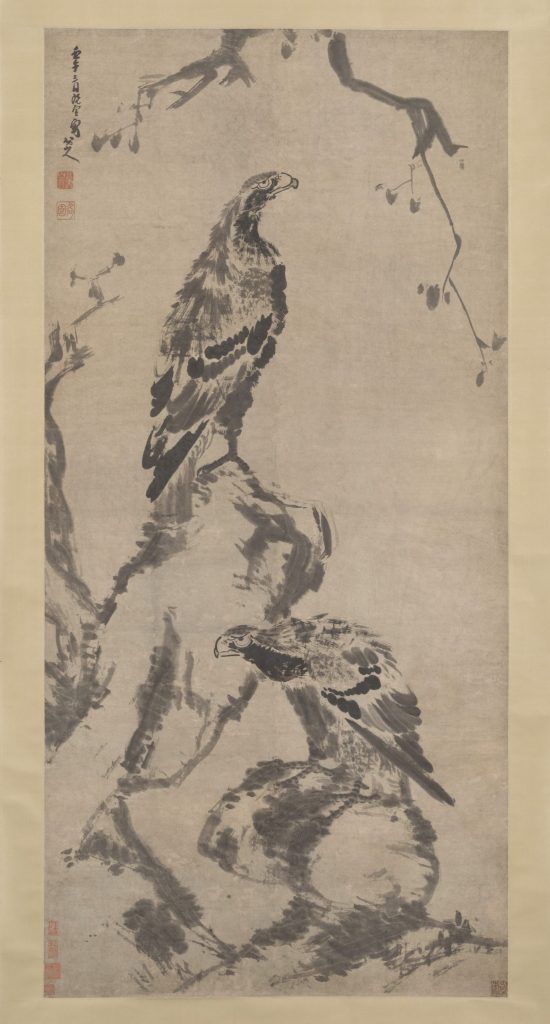

Aside from landscapes, smaller scale subjects such as birds, flowers, insects, fish, rocks, and bamboo became popular themes by the 11th century. Korean literati artists were especially taken with images of tigers (associated with the Mountain God), some so vibrant that they seem ready to leap off of the paper.

|

|

The brush strokes used in calligraphy are very similar to those used in the art of painting, both skills requiring years of practice to master. Young calligraphy students would sometimes be given an egg to hold in their brush hand. By wrapping their fingers around the egg they could properly align their fingers on the brush, which is held in an upright position, very differently from European technique. Students learn each stroke one by one, moving from basic to more complex. Each stroke must conform in general shape to a model, which is usually placed nearby and carefully examined before beginning the stroke. There are also special copybooks that students can use with outlined strokes and lines with arrows that indicate the proper direction of the brush.

Calligraphy and painting are judged by the quality of the individual brush strokes, positioning of elements, and the overall effect of the parts as a whole. The qi life force should be present in every stroke of a painting or calligraphic composition. Likewise, the relation between negative (empty) and positive (filled) space is important, and the “blank” spaces that make up many paintings in East Asia are as crucial in creating an effect as those covered in ink. These features are also important elements in the related art of garden architecture in which the scene shifts as one changes position in the carefully constructed “natural” landscape.

In traditional times landscape paintings were often prized by urban dwellers because of the depictions of wild nature (usually tempered by the addition of a small pavilion or boat, subtly indicating the presence of insignificant humans). Whether horizontal or vertical scrolls, fans, or screens, the paintings were escape portals to another world, in a way like the modern use of television sets (at least the National Geographic channel!) and computer screens. Paintings, especially the larger ones, were designed so that the viewer’s eye enters at a point low on the painting, then follows a winding path through rocks, water, trees, and clouds up through the landscape into the heavens. One very long scroll painting of a river lined with mountains was put on display in the 1980s in a museum in Guangxi, China. The painting stretched through several rooms and allowed viewers to leisurely wander through a traditional “virtual” landscape.

Special tools are needed in the process of East Asian painting. Traditional painters, scholar-officials, and literate women in well-placed families prized themselves on these “precious objects,” which are: paper (or silk), brush, ink, ink stone, water, water container, brush rack or holder, paper weights, name seal, and vermilion ink.

Paper was in many grades and made of different plants, including shredded mulberry bark or bamboo. Ink was made of pine soot mixed with special organic glue and formed into hard sticks, sometimes enhanced by gold paint, molded surface designs, and incense. The ink was ground on an ink stone that was a semi-hard polished stone with a sloping water hole carved. Water from a special ceramic water container was poured into the deep end of the hole, leaving the sloping upper surface of the hole dry.

The ink stick was ground in a circular motion on the stone, occasionally looping into the water so that the ink formed by dissolving a small amount of solid ink into the water. When the resulting ink was jet black and the right consistency, the painter would carefully dip the brush into the ink stone, smooth the tip, and then execute the strokes on the paper, which was held in place by smooth paperweights of jade or other stone. Lighter washes could be obtained by dipping the brush in water.

The brush was carefully made of several inner and outer layers of hair (wolf, rabbit, etc.) that create an ink reservoir inside and come to a point. Brushes had to be carefully hung on a brush rack (made of bamboo or red wood) so that the points would not be damaged. Brushes were placed horizontally on smaller holders when the painter or calligrapher was pausing to examine his or her work.

When the painting was complete, the painter, or another calligrapher would add a short poem, and possibly a signature and date. Finally, the artist would take a specially carved name seal, made of jade, horn, agate, ivory, or other hard substance (plastic is common today!), and dip the end carved with his or her name into cotton soaked with red ink. (This sort of ink, called vermilion, was imported from China to trade with Native American groups in the 18th and 19th century for use as make-up).

The name stamp was then artfully applied to the painting, often beneath the poem. Later owners might also add their name seals. Some paintings in the imperial collections in Beijing and Taibei, Taiwan, have dozens of seals, the largest ones representing the emperor’s ownership. After the seal was applied, the painting was often mounted with organic glues on a background of elegant paper, often in the form of a scroll or fan.

CERAMICS

East Asian ceramics range from the coarse earthenware and stoneware of the common people to the exquisite celadons and porcelains of the ruling classes. The earliest examples of pottery in the world date to Japan as early as 10,000 BCE. However, these early styles seemed to have arisen and died out in Japan without influencing other regions. Later, pottery technology from the northern and coastal China mainland replaced the earlier Japanese styles. Chinese pottery and ceramics include the entire terra-cotta army guarding Emperor Qin Shihuang’s tomb, to egg-shell thin porcelains. Many Chinese kiln sites developed around areas with good clay, including the famous Jingdezhen site in Zhejiang province. Korean ceramics were among the very finest produced in East Asia. The following sections briefly outline the development of ceramics in each cultural area and illustrate most common styles.

China

|

|

Pottery in China dates back about 8,000 years, to the Neolithic period. These Neolithic styles, evolved before glaze was invented, include the yellowish-orange Yangshao pottery from the Yellow River region and the black Longshan pottery from coastal areas. By the Shang dynasty ceramics were in use for daily and ritual purposes. Bronze casting technology is closely linked with early methods of pottery production that used molds. By the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE) ceramic art had evolved to the point where massive armies of thousands of soldiers and horses could be constructed and buried with the emperor.

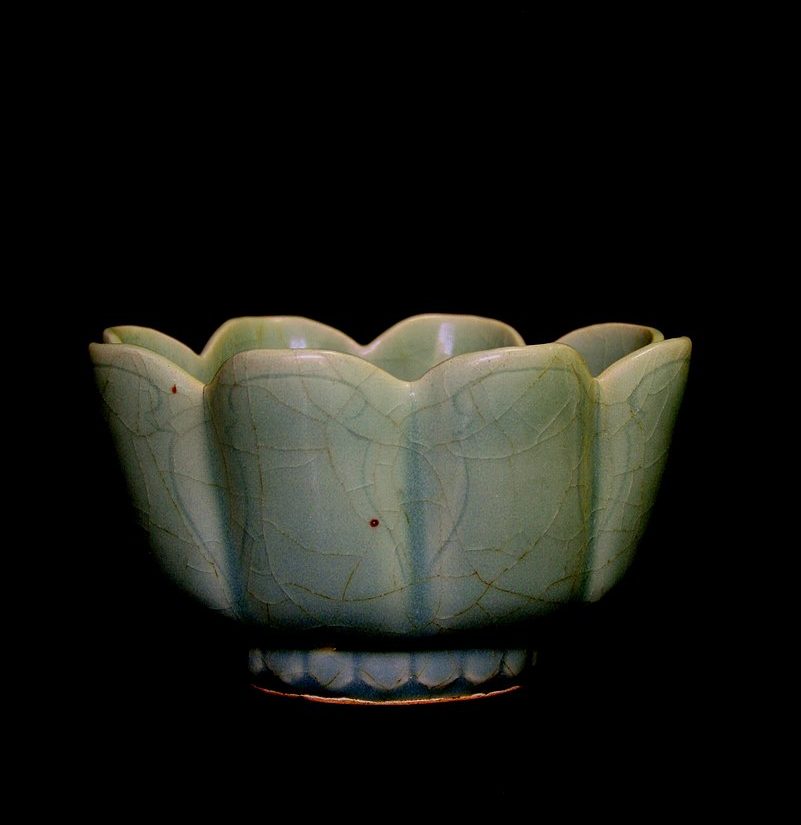

During the Silk Road era many types of pottery developed. Most famous are the large horses, camels, and humans decorated with a three-color glaze (white, yellow, and green). By the ninth-century, celadon (qingci in Chinese) was developed in China and soon spread to Korea. Bluish-green celadon was the favorite of emperors in the Song dynasty and famous styles included Ru ware and Jun ware.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

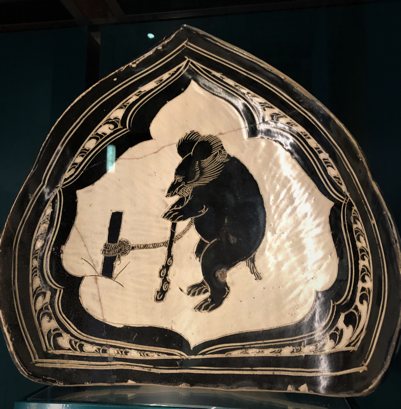

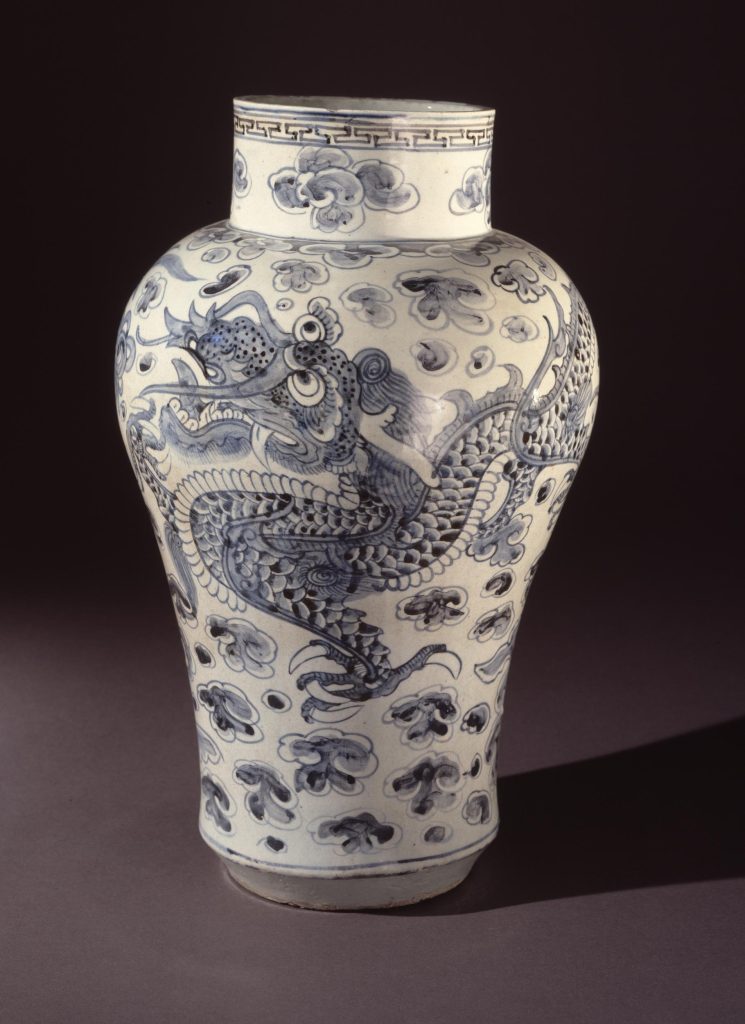

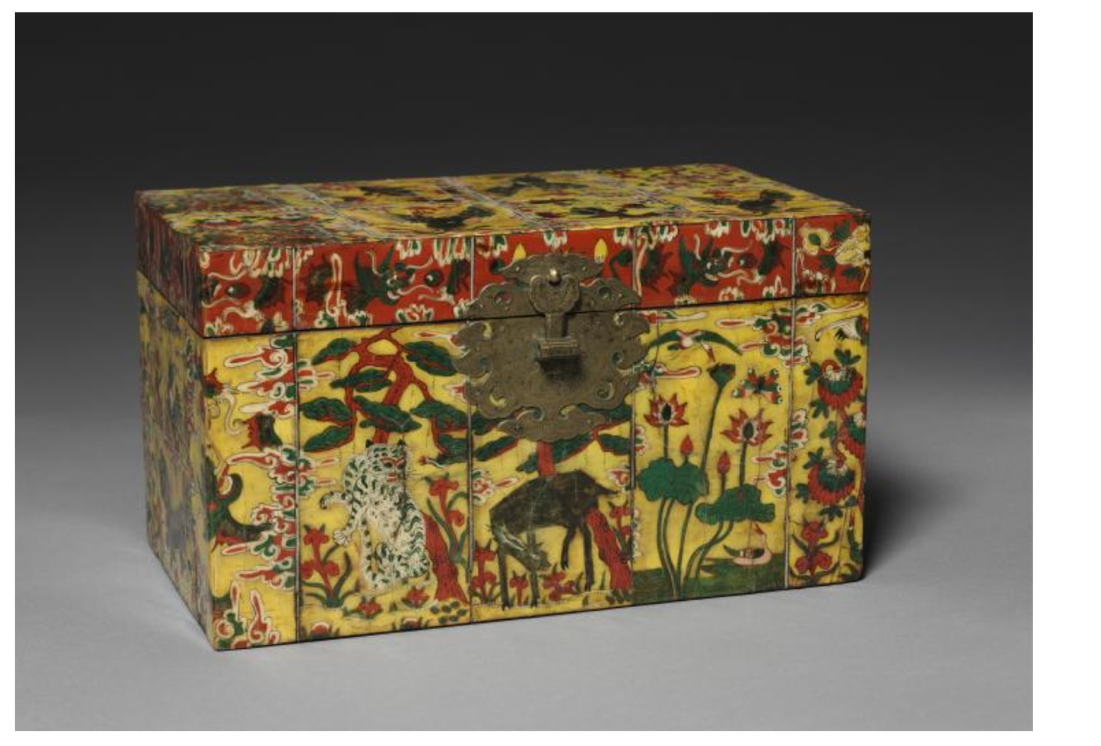

During the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368 CE), cobalt blue from Persia was used to decorate white porcelain, creating a style of blue and white ceramic that would reach its peak in the Ming dynasty. As each emperor came to power, styles and markings changed, many of which were faked in later centuries. Jingdezhen in Jiangxi was among the most famous of the kiln centers where pottery was made and fired. In the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), white porcelain decorated with five colors became popular, featuring images of birds, flowers, insects, natural features, and domestic scenes. Some porcelain was made specifically to suit foreign tastes.

Pottery is still made at several centers in China, including Jingdezhen. A very active fakes market is also in play, with hundreds of newly made “ancient” items for sale on the Internet.

Korea

In Korea, early earthenware pottery dates back 6,000 to 7,000 years. Fired pottery, called stoneware, was in production by the third or 4th century CE. A type of grayish-black pottery with a dull “ash” glaze was made in Silla and Gaya during the Three Kingdoms period, followed by the development of greenish glazes. By the 9th century, celadon had been introduced from pottery centers like Yuezhou in Zhejiang province of China.

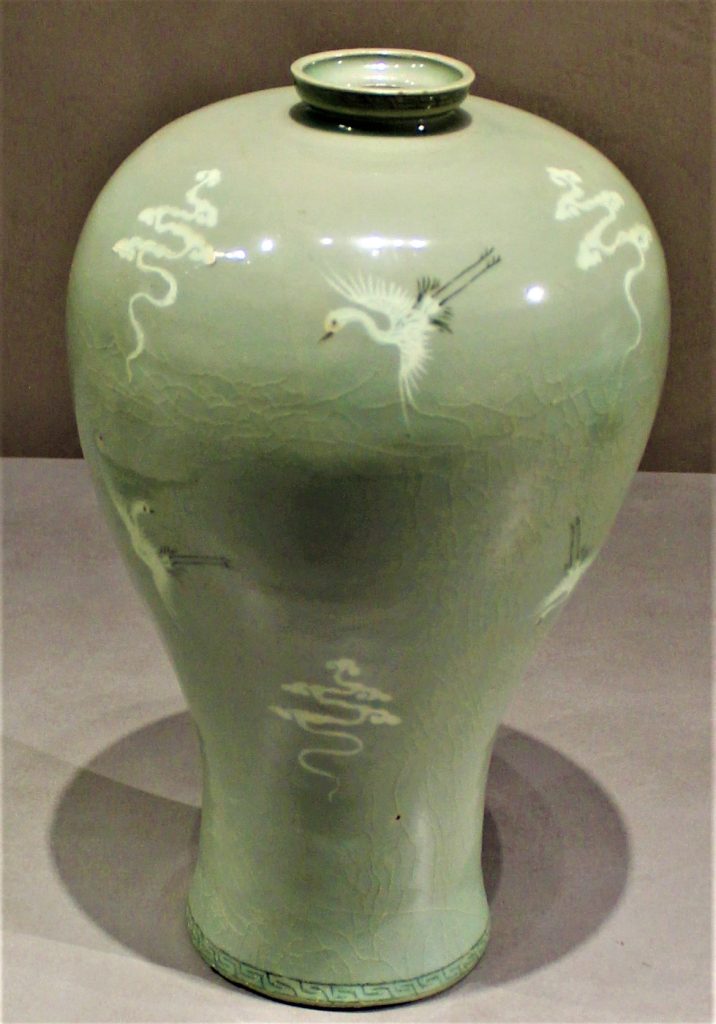

Celadon became the most valued ceramic in the Goryeo Dynasty, and by the 12th century, the Korean potters had developed intricate processes of incised and inlaid designs in the exquisite greenish-blue celadon. Special knives are used to cut into the soft clay after which different colored clays are inserted before the piece is glazed in the firing process.

|

|

|

|

Fine Examples of Goryeo Celadon |

|||

|

|

During the Mongol invasions, the secrets of celadon manufacture were lost and a simpler, earthy style of stoneware pottery called buncheong ware came into fashion. By the 15th century, blue and white porcelain patterns were introduced from China, followed by decorated white porcelains in the 16th and 17th centuries.

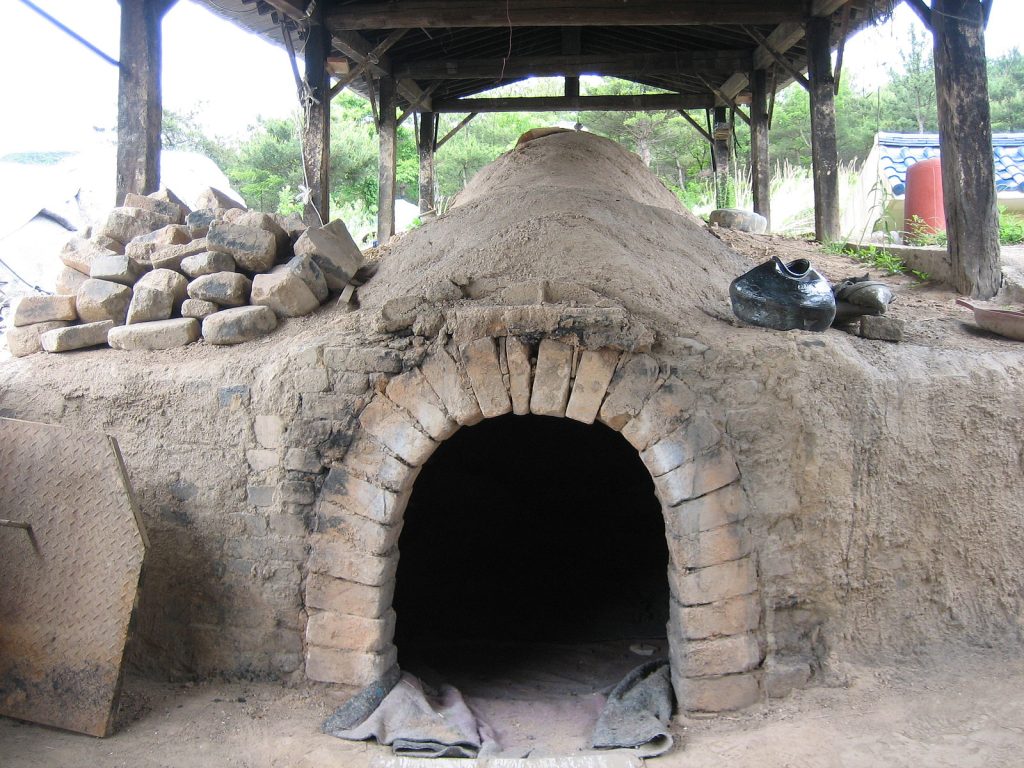

Today, ceramics are still very popular in South Korea, and working can be found in a number of areas, including the ancient Silla capital of Gyeongju. A traditional kiln was made in the form of an above-ground tunnel and situated on a gently sloping hillside. Pieces of unfired pottery were stacked higher inside the long kiln, and wood fires were carefully tended to get just the right heat.

|

|

A contemporary sculpture by artist Yeesookyung (Yee Soo-kyung), South Korea, made of shards of Goryeo celadon found along the North Korean border, skillfully epoxied together and laced with gold. She is best known for her sculptures made of Joseon dynasty broken ceramics called “Translated Vases.” This sculpture was acquired by the Grand Palace, Paris.

Japan

As noted, the earlier cord-marked pottery of the Neolithic Jomon period was replaced by styles from the continent during the Yayoi Period. Arriving approximately between 300 BCE and 300 CE, the new styles were made of finer clay and though plainer in shape than the highly decorated Joman styles, were thinner and more graceful. Typical colors were red and black. Haniwa figurines are an outstanding example of ceramics from the Tomb Period. Human figures, horses, and objects from daily life made of tubular pieces of clay were buried with the dead.

|

|

|

|

|

By the 6th to 7th century, ceramic influences from China and Korea were very strong, as were other elements of continental beliefs and material culture. Lead-based glazes were imported from China, and used extensively on stoneware in styles of pottery reminiscent of those on the continent. With the rise of samurai culture between 1185 and 1568, the aesthetics of Zen Buddhism became pervasive and influenced the development of pottery. Most famous is the raku ware associated with the tea ritual. The word raku literally means “pleasure” and is associated with the Sen no Rikyu school of the tea ritual in the 16th century. Raku ware is shaped by hand (instead of on a potter’s wheel), fired at relatively low temperatures, and cooled quickly, creating “natural” patterns that include cracks and burn marks. Such features are contemplated at certain points in the tea ritual.

|

|

|

|

|

|

By the late 16th century, decorative pottery also came into fashion. During the 17th and 18th century blue and white porcelain styles from the continent were in vogue. Many creative styles of Japanese pottery also developed in this period and Japanese porcelain is highly regarded today.

|

|

|

|

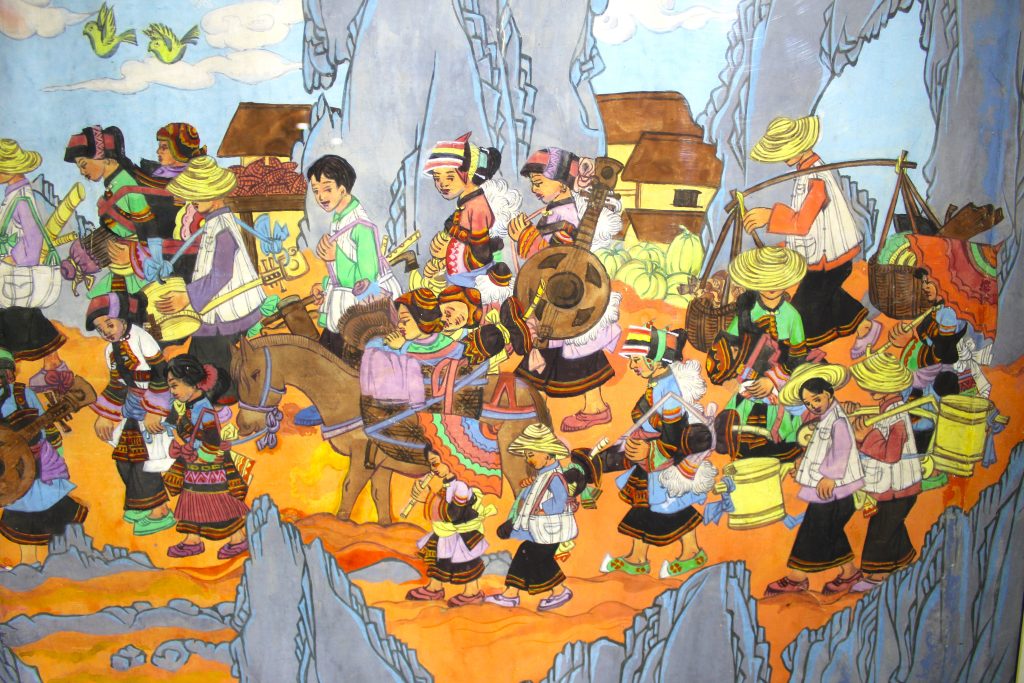

“PEOPLE’S ART”: POPULAR AND FOLK

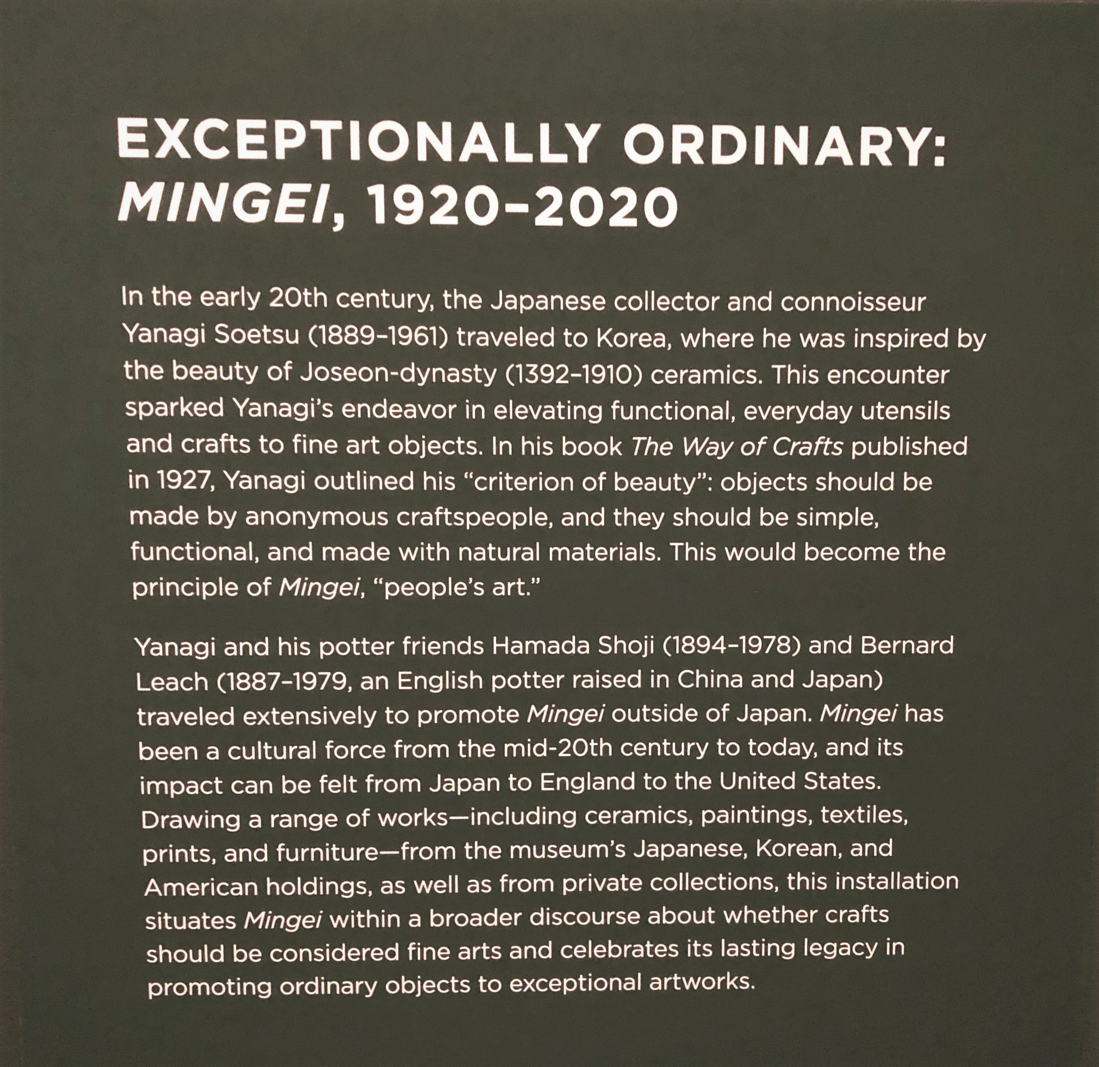

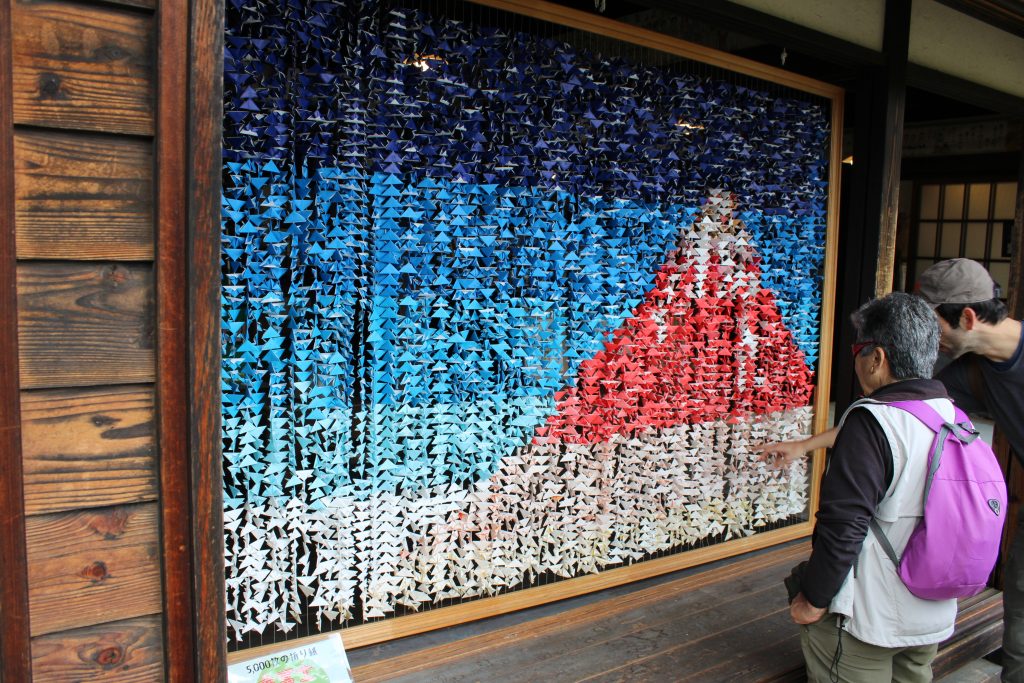

Early 20th century Japanese scholar Yanagi Soetsu (1889-1961) was the founder of the mingei or “people’s art” appreciation movement in the 1920s, inspired by everyday objects he saw in use in Korea. The line between popular/folk art and elite art is often blurred, as in the oral and written verbal art traditions in East Asia. The wording about mingei is from a Seattle Art Museum exhibit. (Photo by Mark Bender)

Paper Items

Works of art for popular consumption and everyday use have a long history in East Asia. Of special note are those using paper. Paper was officially invented in China in 105 AD, by an official named Cai Lun, and eventually the process became an art form in itself. The process of producing a single sheet of paper could take several months, but when finished, the paper was ready for use as a medium for anything from calligraphy, painting, printing, or paper folding.

These 5 woodblock prints depict each of the major steps of the paper making process in ancient China. Similar processes were used in Korean and Japan.

- (1) Certain plants, especially the bark of mulberry or bamboo fibers, are gathered and broken down to be mixed with water, forming a slurry.

- (2) The fibers in the slurry are cooked then laid out in the sun to dry.

- (3) The dried fibers are pounded, then mixed in water again along with a gelatinous agent. Once thoroughly mixed, it was scooped onto a bamboo screen to form a thin sheet.

- (4) The paper is then stacked with felt between each sheet and pressed to squeeze out the excess water.

- (5) The sheets are brushed onto a flat wall to dry.

Images printed on paper with carved woodblocks became very popular by the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) in China. Some of the most popular items were good luck pictures (nianhua) displayed in homes and on doors at New Year’s in both China and Korea. Pictures were produced on various grades of paper and sometimes were multicolored, applied with a series of different blocks. Popular prints included the Eight Immortals, God of Wealth, and the ghost-catcher Zhong Kui, who is often accompanied by a bat, a symbol of good luck (the word for “bat” and “good luck” are the same in pronunciation in Chinese) in the pictures. In rural areas of China, doors are often guarded by colorful paper posters of ancient generals known as “door gods” (menshen) who are pasted on the outside doors to protect the families from unlucky forces.

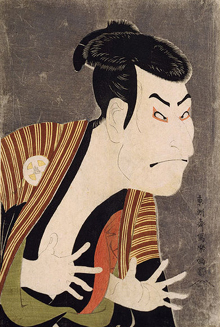

In Japan woodblock images (ukiyo-e) were all the rage in the Tokugawa period and famous woodblock artists like Utamaro, Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Toshasai Sharaku mass-produced images of entertainers (much like movie star posters today), scenic sites, and daily life. Besides woodblock prints, painted scrolls called emaki were also popular in Tokugawa Japan.

Everyday Items

Everyday objects including tools, household and personal items, and architecture were often constructed in patterns developed and handed down over centuries, sometimes acquiring a perfect combination of pleasing aesthetic form and function. Many objects were decorated in a variety of ways that included painting, engraving, cutting, or more complex processes such as cloisonné. In many cases there was an emphasis on the relations between natural elements, such as stone and wood in village homes in Korea and Japan. Textiles of wool, cotton, silk, hemp, and ramie were used to create costumes and ornaments—resulting in folk art that was worn. Men and women in the societies were often skilled in a variety of handicraft arts, though in some cases there was specialization.

|

|

|

|

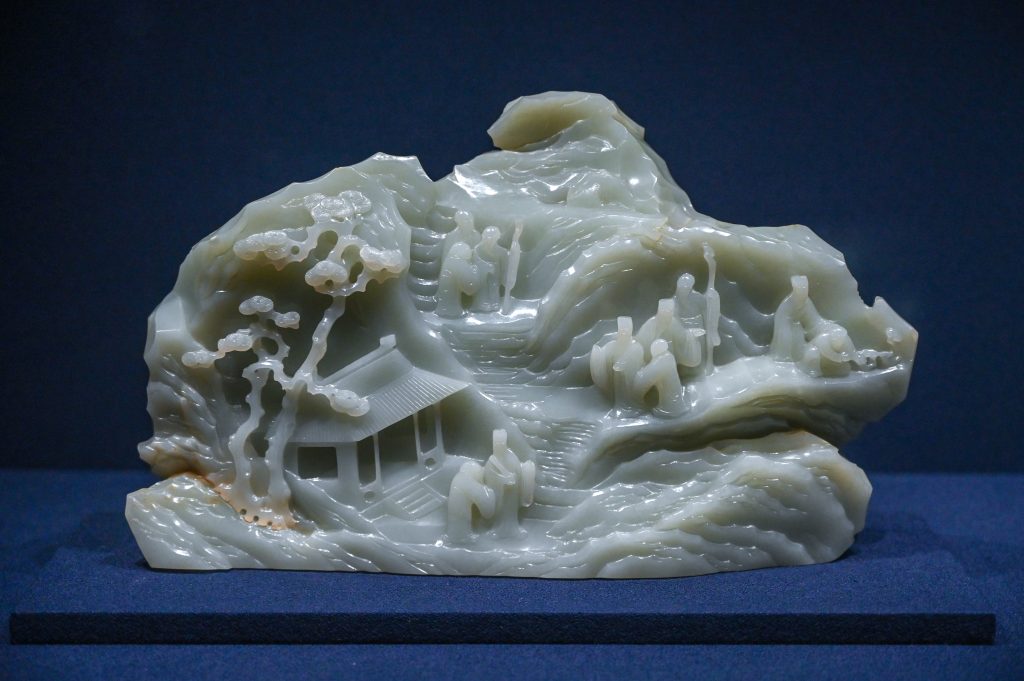

In some cases decorated items had specific functions (such as the hanging pot-holders on traditional Japanese hearths or the good-luck tokens that protect the home), while in other cases, items were there for enjoyment. This was especially so in the case of miniatures that were appreciated by merchant and upper-class people who could afford artistic luxury items. Miniatures were small items made of a variety of materials by craftsmen who used jade, ivory, bone, lacquer, horn, amber, and other materials, often enhanced with intricate carving and engraving. Cloisonné, a technique using powdered ceramic of various colors daubed into wire armatures, was used to decorate bowls and jewelry items. Gift stores in East Asia are filled with such items in varying quality that are produced for the tourist trade.

|

|

Very often personal items like hairpins and other jewelry or personal hygiene items (earwax-scoops, fingernail maintenance tools, etc.) were usually decorated. Such items were made of silver or gold (for the upper-classes) and decorated with precious stone inlays. Small silk purses, vest pendants (called norigae in Korean), tiny “chastity-protecting knives” (in Korea) and other items of women’s clothing were often decorated with embroidery, knots, and tassels fashioned in auspicious colors patterns.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the wood-rich areas of Korea and Japan, wood carving is still a popular folk art. Items include images of village protector gods in Korea as well as bowls, trays, buckets, chests, mirror-boxes, clogs, window frames (for supporting paper covered windows), and masks used in traditional drama. In parts of southwest China, some local artisans still make traditional musical instruments of wood, bamboo, and leather.

|

||

|

|

|

Korean masks from local styles of talchum folk drama. |

||

Nihonto: Japanese Swords

Arms and armor in Japan were often decorated and involved the combination of several mediums including iron, steel, brass, copper, wood, bamboo, leather, ray skin, and other materials. The Japanese have long been regarded as the foremost producers of swords, and well-made ones were regarded as works of art by the samurai and well-heeled collectors today. By the later 16th century, the samurai began wearing two swords stuck in the waist band—one longer one (katana) and a shorter one (wakizashi), for use indoors. Swords made before about 1600 are known as koto (“ancient swords”), while those made in the earlier part of the Edo period up to the later 18th century are known as shinto (“new swords”). Swords made between the later 18th century and early 20th century are known as shinshinto (“new new swords”). By 1876 the samurai were no longer allowed to wear their swords in public. In the 1930s and 1940s many battle swords were made by machine, though are of no interest to collectors of the older art swords and are illegal to own in Japan today.

The golden age of sword making was around the 13th-14th centuries. Swords were traditionally made by hammer-welding a core of layered steel within an envelope of iron to create a sharp but not overly brittle blade that could absorb the shock of battle. The majority of older blades (pre-1900) have a temper line (hamon) in the steel that tends to be lighter in color than the softer parts of the blade. The line was made during the forming, polishing, and tempering process. The final step involved placing wet clay on the blade and cutting away a portion so that a pattern would be formed when the hot sword was dipped in water for hardening, creating patterns of martensite crystals in the steel. Experts can identify a whole range of “activity” in the hamon and other parts of blade that include misty lines that appear as clouds or rising mist over a range of mountains, tiny bright dots, and patterns in the folded iron (called “grain,” as some patterns seem like wood). The nature and quality of the activity on the blade can make the difference in value from a few hundred dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The appreciation of the fittings (koshiarae) and blades involves aesthetics similar to those in appreciating Zen styles of pottery, painting, and calligraphy. In terms of appreciating a hand-forged blade, several points are considered. These include the overall shape and proportion of the blade, the presence or absence of a signature on the tang (the metal part of the handle that is usually hidden from view by a wooden, silk wrapped handle). Other aspects of the tang include the apparent age and texture of the rust (which gives clues about the age and should never be disturbed or removed) and the pattern of file marks. One also tries to determine if the peg-hole that attaches the wooden part of the handle is punched or drilled—the difference being an indicator of age (the punching technique tends to be older). The blade itself has many features that indicate age, origin, and aesthetic value. The sword guards, or tsuba, come in many styles and are appreciated on their own merits and in harmony with the blade and other fittings. It is interesting that sword collectors outside Japan also use Japanese terms to describe the aspects of the traditional swords and their aesthetic aspects—making sword appreciation a good way to learn a highly specialized vocabulary of Japanese words.

The most famous of the Japanese sword smiths was Goro Nyudo Masamune of Soshu who lived at the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century. Like the art of ceramics and other skills, the secrets of swordsmithing were well-guarded secrets. According to one story, Samonji, the favorite of Masamune’s eleven pupils (and future son-in-law) stealthily attempted to test the water in which a sword was being tempered. Since such secrets were only revealed at the master’s whim, Masamune took offense and immediately lopped off his pupil’s hand. Samonji later died in disgrace at age thirty. Another pupil, named Sadamune, wedded the master sword smith’s daughter in 1321.

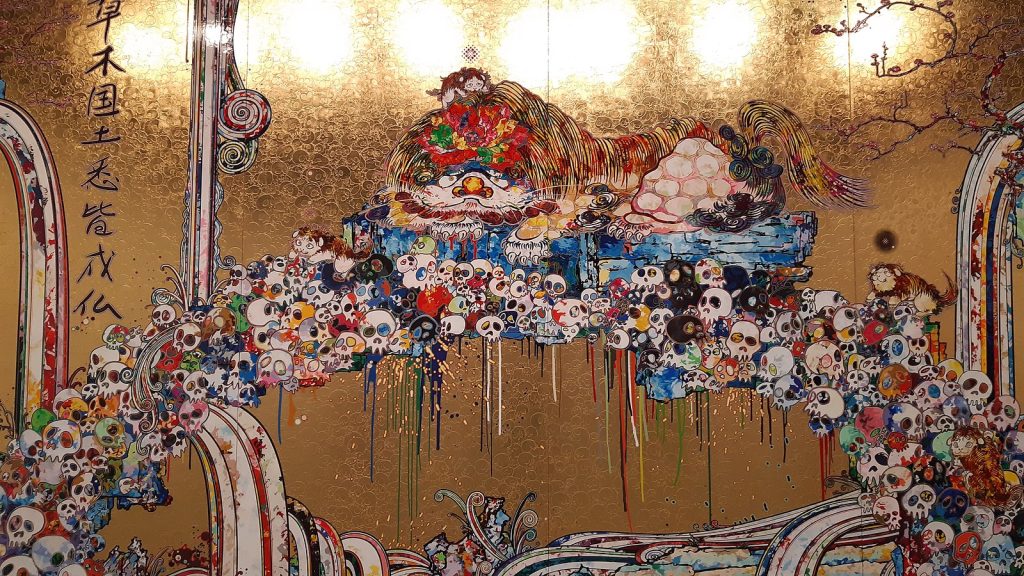

MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART

In East Asia today, traditional arts exist side by side with Classical Western art, Modern art, and what can only be described as “fusion” art, much like the coexistence of Eastern and Western cuisines and other cultural features. Avant-garde artists inhabit major cities all over East Asia, with the exception of North Korea, which is still involved in “socialist realism”—art for society’s sake, rather than “art for art’s sake.” In sum, contemporary art in East Asia today is an exciting mixture of past and present, native and foreign.

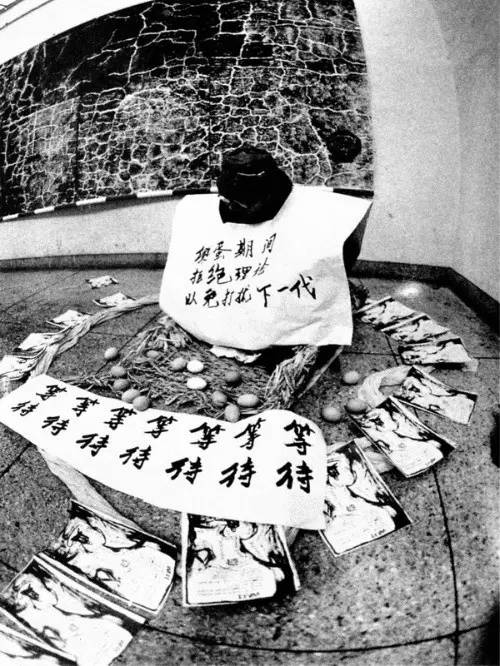

The modern period of art in East Asia begins in late 19th century Japan, where trends quickly followed those developing in Europe. By the early 20th century, the impact of Modern art was being felt in China and Korea as well, with the new styles of art carving out space amidst the traditional ones. The re-emergence of Modern art within China during the 1980s and ‘90s after decades of socialist realism was one of the most fascinating chapters in contemporary East Asian art. By the early 1980s, avant-garde artists like the “Stars” group in Beijing were experimenting with Western conceptual art in the mediums of painting, sculpture, and photography. Despite occasional government disapproval, even extreme “conceptual” artists have displayed their works and continue to test the limits of creativity and public acceptability. (One work, in the mid-1980s, featured the artist gingerly crouching upon a square filled with uncooked eggs.)

Other departures from the past include an interest in nude subjects in painting and photography. Increasingly common is civic sculpture, often abstract, and sometimes involving local mythology. In recent years China has become a premier site for experimental architecture and cities including Shanghai, Beijing, and many smaller places have seen the erection of a huge number of architectural wonders—some that pass beyond aesthetic expectations of anywhere else on earth.

|

|

Modern sculpture was introduced in Korea in the 1920s. Since then many fine works in abstract and realistic styles have been produced in bronze and iron, especially in the last two decades. Urban architecture is also important in Korea, and public buildings such as sports stadiums, performance halls, and museums are state of the art.

|

|

The art and aesthetics of East Asia continue to exert a powerful creative influence on societies around the world, ranging from the influence of traditional calligraphy to car and home appliance design and artwork.

|

|

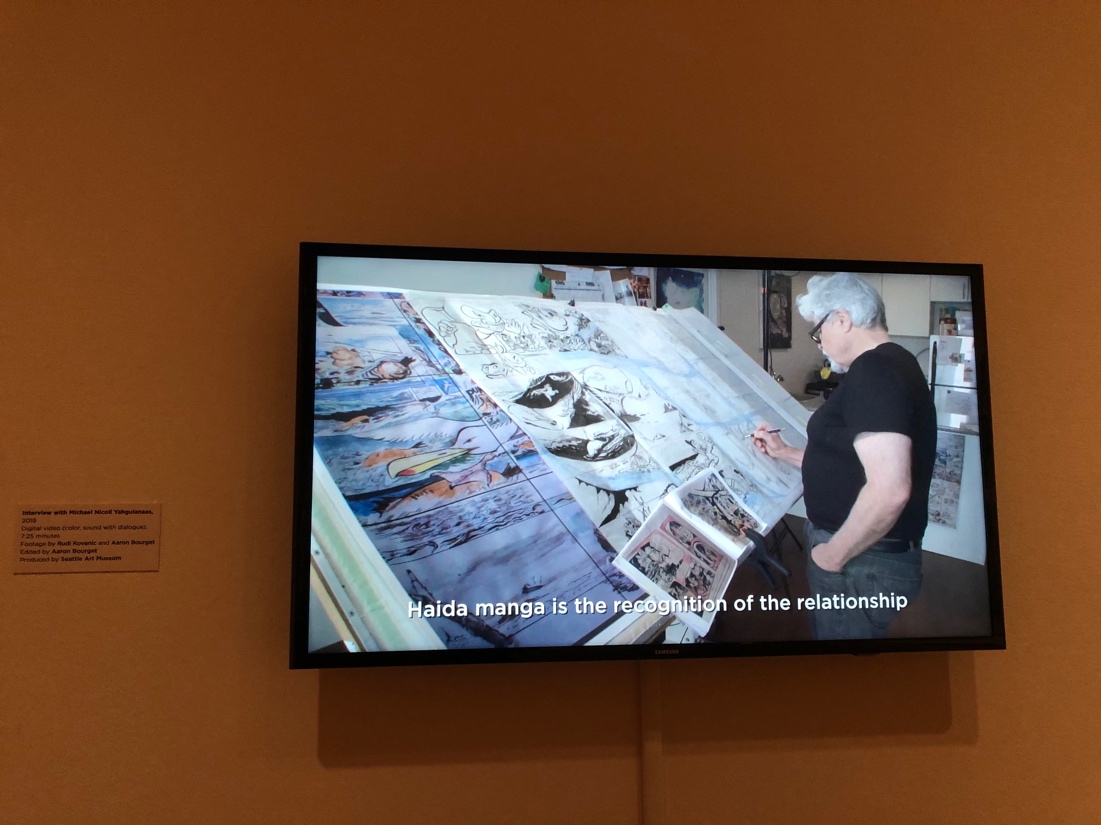

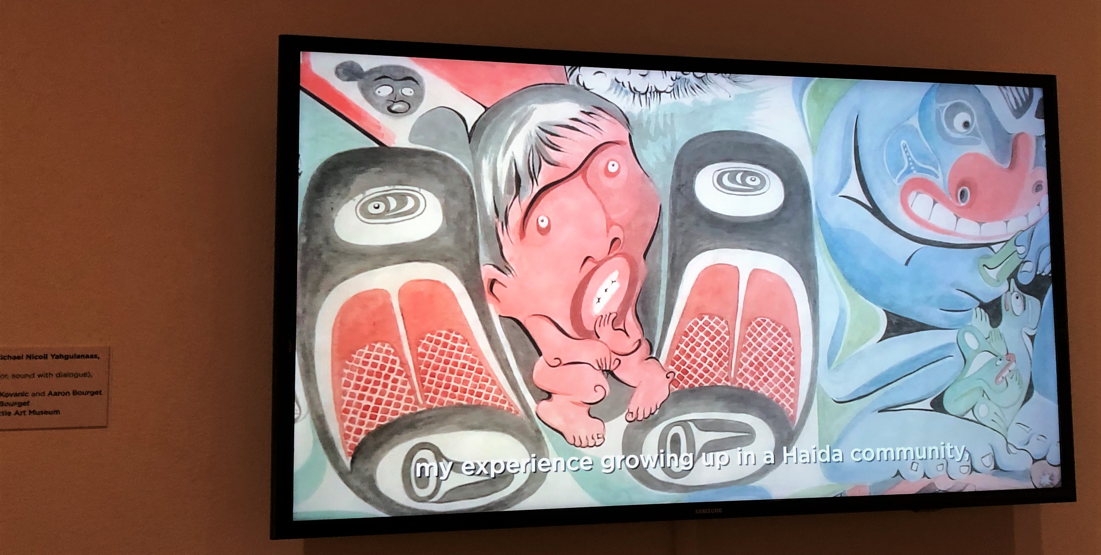

Michael Nicoli Yahguianaas is A Haida First Nations artist from the North Pacific islands who was inspired by Japanese manga cartoon art to create a fusion between traditional Haida art and Japanese manga style. He recently exhibited his work in the Seattle Art Museum which commissioned a work called “Red” integrating traditional Haida mythology in manga style. (Photo Mark Bender)

|

|

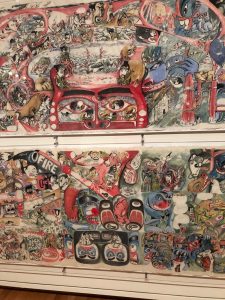

Detail of “Haida manga” fusion art by First Nations artist Michael Nicoli Yahguianaas in Seattle Art Museum. The images on each side of the depicted person represent killer whales in traditional Haida wood carving and silverwork. (Photos by Mark Bender)

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

- Japanese Arts

- Single Stroke Painting – A short National Geographic video about the Japanese art of single stroke painting

- Japanese Printmaking – A Japanese master of printmaking demonstrates and explains his process. The uploader considers it “unintentional ASMR”

- Japanese Garden Lanterns – A YouTuber interviews a Japanese garden specialist about the stone lanterns that are commonly found in Japanese gardens

- The Great Wave by Hokusai, Explained – A fascinating explainer video about Japan’s most famous painting

- Floating Flower Garden Tour – A video tour of a modern interactive art exhibit by teamLab Planets Tokyo

- Chinese Arts

- Chinese Calligraphy – A video from “Asian Art Museum” helping viewers learn how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy

- James Cahill Lecture on Tang Landscape Painting – A full UC Berkeley lecture by art historian James Cahill (1926-2014) on Tang landscape paintings. It is part of a series of lectures Cahill gave on Chinese art, and is well worth exploring if time permits.

- Master of Nets Garden, Suzhou – A virtual tour of one of the famous gardens of Suzhou, complete with explanations of the reasoning behind it

- Jingdezhen Porcelain – A CGTN feature on porcelain from the renowned Jingdezhen kilns, discussing their history and design

- Knock-Offs to Original Art – A news report on the turn of China’s knock-off artists towards original works in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic

- North and South Korea

- North Korean Propaganda Posters – A short video displaying 18 propaganda posters from the DPRK and their translations

- Modern Art – A video discussing the characteristics and impact of South Korea’s modern art movement

- Reviving Korean Celadons – A video from 2009 about South Korea’s attempts to revitalize celadon production

- Korean Architecture– A short documentary by the Korea Foundation about the characteristics of Korean architecture

- Korean Art at the Cleveland Museum of Art – A video showcase of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Korean art collection