10 Module 9: Popular Culture in East Asia

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

OUTLINE

INTRODUCTION

Popular culture comprises aspects of culture relating to entertainment, excitement, diversion, enjoyment and self-cultivation, especially those phenomena that cross social, economic, age and other divisions to touch large populations. It tends to be associated with urban life, but modern communications send new ideas, trends, memes and television shows around a country—and often the globe—almost instantaneously, amplifying both the reach and the impact popular culture. Historically, East Asia’s greatest expressions of popular culture are associated with periods of stability and wealth when merchants, shopkeepers, artisans, and other “middle class” people, those with means and leisure, enjoy and explore life beyond paid work and other subsistence activities. While what we define as folklore is largely “homemade” at the local level, popular culture tends to involve more complex levels of commodification and dissemination through mass media. (See Module 7 for many examples of traditional performance genres that are part of the popular culture heritage of East Asia.)

In East Asia, up to the early 20th century, popular culture might mean public staging of plays or storytelling by professionals; large-scale festivals and associated opportunities for the consumption of food, incense, firecrackers, floats, and other festival paraphernalia; the printing and dissemination of woodblock print images, opera librettos, song lyrics, and pulp fiction.

Whole districts of many cities were given over to the specialty consumer goods that give life flavor, such as shops for tea, tobacco, jewelry and cosmetics, wines, antiques, gaming equipment, musical instruments, herbs and spices, snacks, handicrafts, antiques, items to support hobbies such as flower arranging, bonsai trees, and pets, and other goods that required discretionary income. Other urban areas might offer entertainments that ranged from acrobatic spectacles, musical ensembles, storytelling, plays, and animal acts. Many major urban centers had districts featuring restaurants, wine shops, tea houses, and a variety of other entertainments.

With the introduction of the electronic age in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, mediums for popular culture expanded into the realms of film, radio, and television. Beginning with innovations in transistor technology in Japan in the 1950s, the technology industries of countries in East Asia have competed vigorously and sometimes dominated the development, production, and sale of generations of technology products from products like the Sony Walkman to high tech cameras, computer games, DVD technology to computer hardware and software; and more recently, robotics, virtual reality devices, and multisensory videogames. The popular culture scene in East Asia today as in most of the developed and developing world also includes pop music, live concerts and clubs, fashion, videogames and gaming culture, comic books, and anime videos, athletic events, and vibrant film industries. For individuals, technology has brought a wealth of tools and opportunities for self-expression, artistic production, and social networking—from platforms like TikTok to live-streamed gaming, cell phone photography to fashion blogging—all of which contribute to and help define a networked, increasingly global, but endlessly diverse popular culture. For nations, popular culture can contribute to increasing global influence through “soft power” and the input of popular culture into local and national economies is enormous.

POPULAR CULTURE IN CHINA

Records of China’s rich history of popular culture date from the Zhou period (1046-771 BCE). Periods of the Han, Tang, Song, and Ming were noted for the volume and variety of popular cultural expression. Many of the traditions from these eras continued in recognizable forms into modern times and strongly influenced culture in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam.

In the Tang dynasty, urbanites had access to a full range of entertainments that included carnivals that are said to have their origins in national drinking feasts promoted by the first emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi (Benn 2002: 154-157). By the Tang period, such state-sponsored events celebrating momentous occasions came to involve feasting, drinking, parades, and sideshows on the main city streets. According to ancient sources, as many as 30,000 singers, dancers, and other entertainers might be commissioned to perform at these events and festivities could last from three to nine days. During these parades, giant floats—some filled with musicians and rising to 5 stories high—were drawn down the streets. Such floats, often on the platform of a cart, may have been inspired by Buddhist practices in India and came in many shapes. Some were made to look like mountains, boats (powered by people walking inside), elephants, or even rhinoceroses. Eventually, even private families sponsored their own floats. Though the huge floats eventually died out in China (smaller ones survived in some areas), the floats used in community festivals in Japan today are direct descendants.

Among the entertainment acts at such festivals were itinerant performers who usually plied their trades in marketplaces or the private mansions of the wealthy. These included acrobats, jugglers, wrestlers, illusionists (including vanishing acts and acts involving the dismemberment and reassembly of a magician’s body parts), animal acts, dancing, small-scale theatrical performances, puppets, and storytelling. Forms of many of these activities are still practiced in China today. Chinese acrobats, for instance, are regularly part of international entertainment acts, such as Cirque d’Soleil.

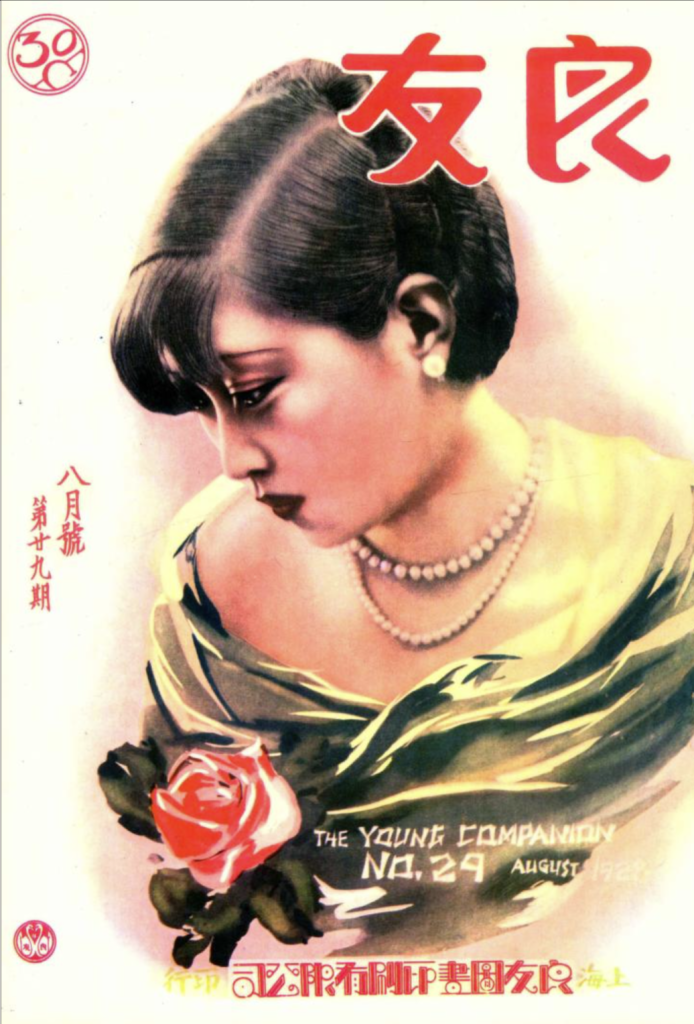

Modern popular culture started in China in the late 1920s and early 1930s in Shanghai. Shanghai was the country’s most open international city at the time because of a tradition of international trade and capitalism and residential districts known as the “foreign concessions” that were enclaves for foreign businesspeople and adventurers. As in Japan, jazz, Hollywood, radio advertising, and the expansion of Western-style newspapers and publishing techniques had an enormous impact during this period. Young women, sometimes smoking and scantily clad, were the subject of many advertising campaigns for tobacco and other luxury goods manufacturers. This freewheeling “party” was winding down by the mid-1930s, however, with the full-scale invasion of China by Japan. After years of war and conflict that ended with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Western-influenced popular culture was to remain out of political fashion for the next several decades.

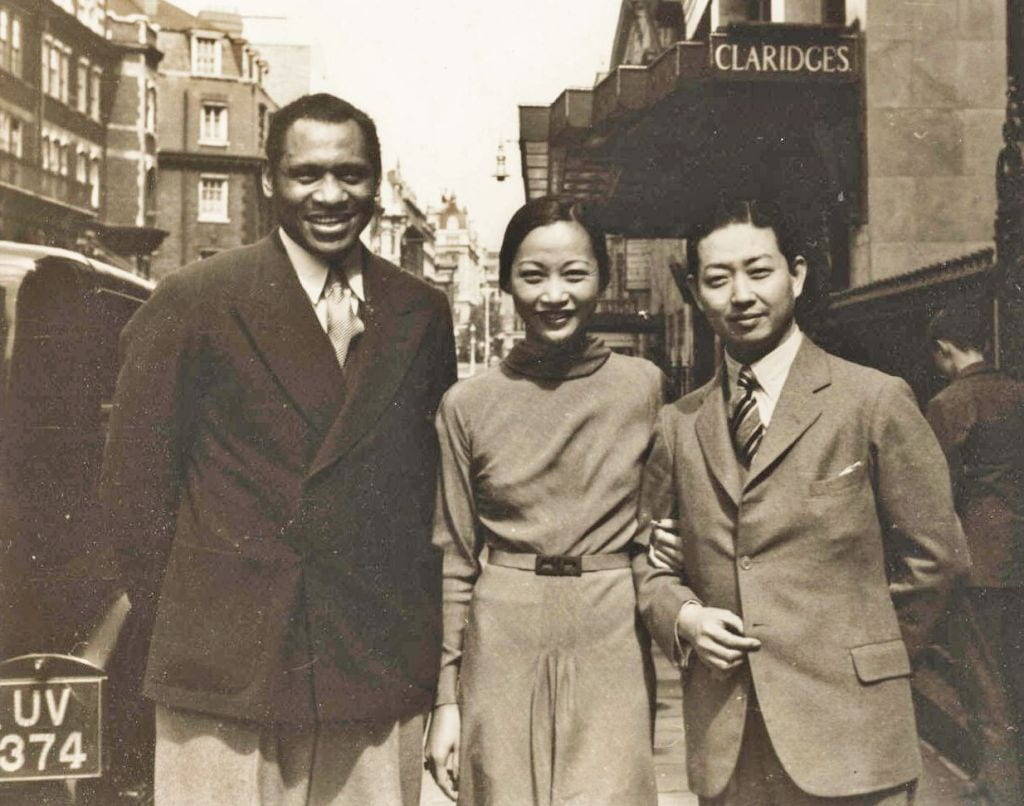

In 1940, American polyglot singer and social justice activist Paul Robeson (1898-1976) sang in Chinese and English a song written by activist playwright Tian Han with music by the composer Nie Er in New York City. The song is entitled “March of the Volunteers” (Yiyongjun Jinxingqu), which was a rousing cry for the Chinese people to “rise up” (qilai/chee lai) and throw off the shackles of oppression. The song had originally debuted in a 1935 film called Children of Troubled Times, and became popular during the Nationalist era. In 1949, the song was adopted as the national anthem of the People’s Republic of China. In 1941 Robeson cooperated with the conductor of a Chinese youth chorus named Liu Liang-mo to record the record album “Chee Lai: Songs of New China.” (cflac.org.cn)

Nie Er (left), a composer from Kunming, and playwright Tian Han (right) collaborated on the “March of the Volunteers.” Tian Han composed the words in everyday vernacular Chinese. The original first line goes, “Arise, all those who wish not to be slaves.” (In 1978, the lyrics were revised to reflect the political agendas of the day.) Nie Er died at age 23, at sea near Japan soon after composing the music. Tian Han, a powerful artistic voice in the New Culture Movement of the 1920s and 1930s, died during the Cultural Revolution in 1968. He was posthumously politically “re-habilitated” and like Nie Er, is remembered for his accomplishments in China today. (Wikipedia)

|

|

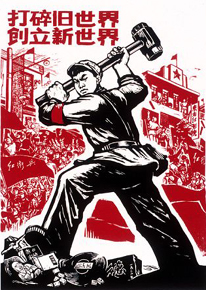

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), images of workers, peasants, and soldiers displaying “revolutionary zeal” were the central themes of poster iconography, along with images of Chairman Mao at various stages in his life. Poster art on traditional and contemporary themes is still common in China, and, along with calendars, sells especially well during the New Year’s festival.

|

|

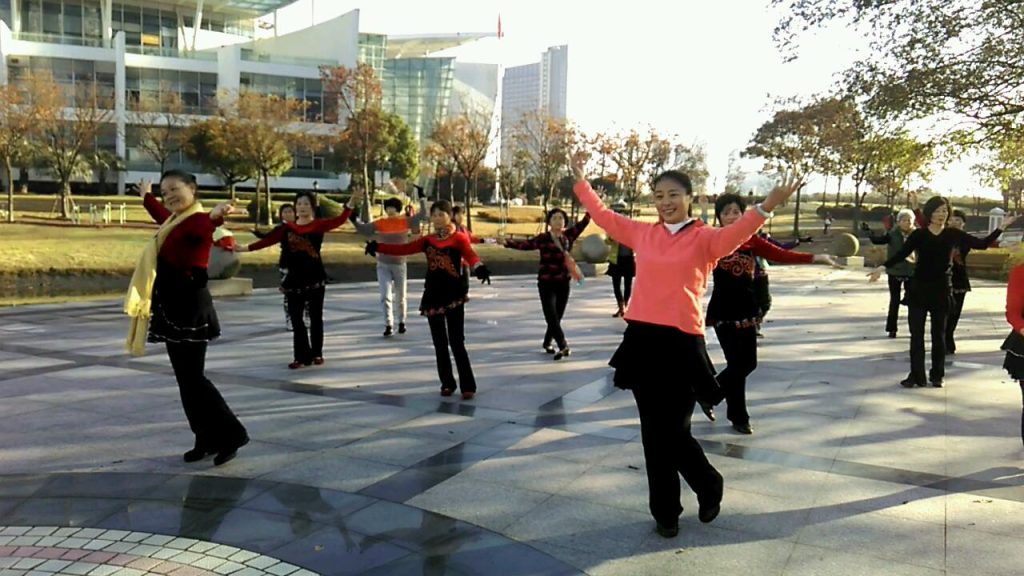

Strait-laced, highly politicized social policies dominated from the late 1940s until the early 1980s. By the late 1980s, what had been a trickle of international books, art, music, popular entertainment, the internet, and ideas entering China had become a flood. Popular culture evolved rapidly as the economy boomed throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. Expressions of sometimes youthful vigor and imagination grew in a political atmosphere that was more tolerant of entertainment for its own sake and public displays of individual creativity just at a moment when globalized media and technology were providing new outlets for consumption and expression. By 2018 a craze for historical drama series, inspired by “Korean Wave” successes, peaked in China with the widely watched “The Story of Yanxi Palace,” about the lives and intrigues of imperial palace women. The government eventually weighed in and asked serial drama producers for more relevant content. In 2021 more government oversight was exercised on social media platforms, including fan sites, individual celebrities, and restrictions on major media companies. There were guidelines promulgated on time spent on online gaming for those under 18, and a pushback against the androgynous look among young male celebrities influenced by K-pop and J-pop stars. All these efforts have been made to tame what has been characterized in state pronouncements as “chaotic” situations in social media and entertainment industries thought to have negative influences on consumers.

|

||

|

|

|

With a consumer base of 350 million online shoppers and increasingly diverse demographics, online-marketing on social media has rapidly evolved in the past decade in China on platforms like Taobao and Douyin (China’s TikTok). Although some government controls have been periodically enacted, livestreaming is a profession for many today. Such marketing and products have become a part of popular culture in China, as in other areas of East Asia and the world.

POPULAR CULTURE IN KOREA

Popular culture has a long history in Korea. With the founding of the city of Seoul in 1399, large markets were established at various parts of the city. Today, hints of the past in the form of traditional pastimes can still be found near the old market areas of South Gate Market (Namdaemun) and East Gate Market (Dongdaemun), though the remnants of the old gates are now surrounded by high-rise buildings. The popular Insadong area is filled with small shops featuring antiques and consumer goods of ages past, tools for calligraphy and appreciating tea, traditional meals and snacks, tailored traditional clothing (hanbok), and art and handicrafts.

|

|

Popular art in North Korea closely follows the dictates of the country’s leaders. Much of it is propaganda art, influenced by the Socialist Realism developed in the former Soviet Union and China. Mass-produced posters of “revolutionary” scenes, such as the images of people working on land once owned by an oppressive landlord, are common. The late leader Kim Il Sung is the subject of many posters, wall paintings, statues, and other public art works. A whole genre of North Korean political popular art is devoted to anti-American themes.

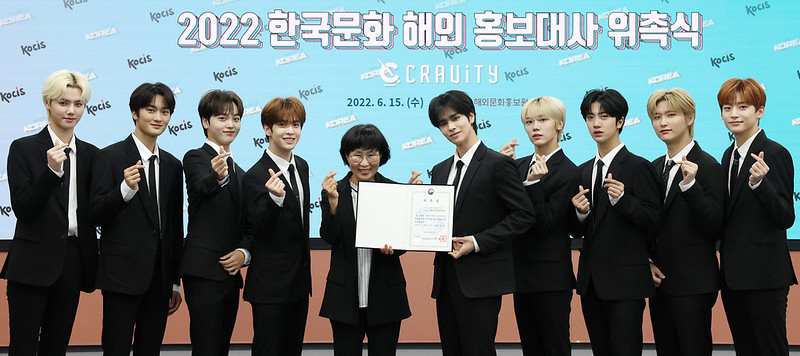

With the growth of democratic institutions in South Korea since the 1980s, pop culture developed to the point that Korean pop music and other forms of popular culture became increasingly the rage in other parts of East Asia and farther abroad. Korean pop music and fashion models have become ubiquitous sights and sounds in China. Korean pop culture represents a new model of individualism and sophisticated consumerism that is an acceptable blend of East and West. This “Korean Wave,” (Hallyu) introduced below, is a major “soft power” measure of South Korea’s development and has placed the country high on the world pop culture stage via social media, the aggressive cultivation of talent, and industry and government interest.

|

|

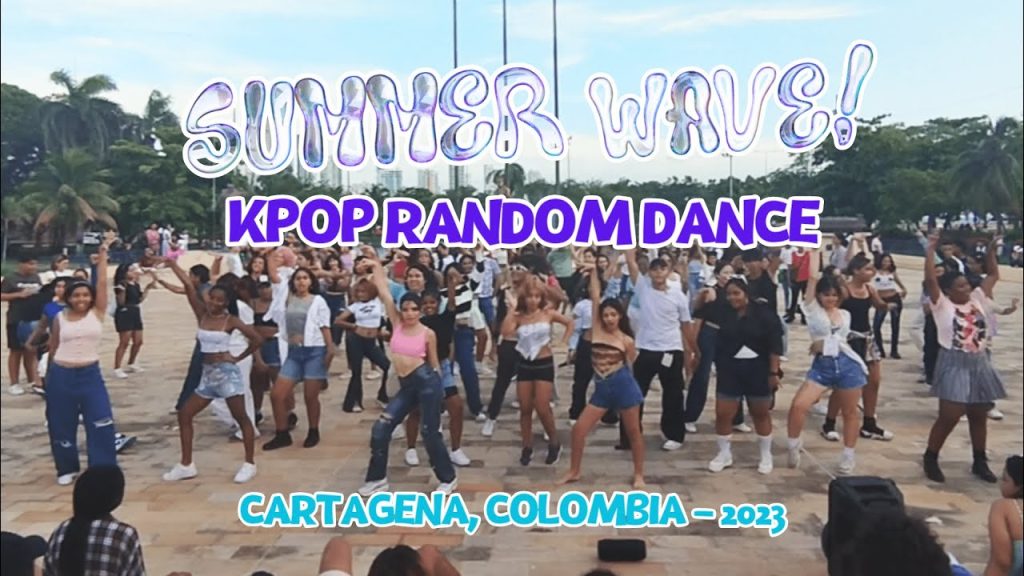

The Korean Hallyu Wave has spread across India, and is especially popular in the Northeast. And around the world, “K-pop Random Play” dances are held in public spaces, where anyone can join and dance along to K-pop songs. The “soft power” engines of music, serial dramas, and the cosmetic/fashion industry are especially powerful drivers of the craze.

During the first two decades of the 21st century a craze for cartoon art in South Korea developed in recent. Between 2000 and 2020, the market for Disney and Japanese animation figures started to shrink and Korean flash animation figures, such as Mashimaro, Pucca, Boomba, and Monya, each with a distinguishing style and characteristics, led a new trend in East Asia. They are seen in different types of merchandise including toys, clothing, cell phone decorations, and stationery and so on, similar to the long-standing Japanese phenomenon of Hello Kitty.

|

|

POPULAR CULTURE IN JAPAN

The high point of popular culture in traditional Japan was the Tokugawa period, spanning from the early 17th century down to the mid-19th century. During this time Japan was at peace and isolated itself from the outside world. While elements of traditions from the earlier periods such as the slow-moving Noh drama and the highly stylized tea ritual were appreciated by members of the aristocratic and samurai classes, the liveliest venues for popular culture were the urban districts frequented by the rising merchant class. This was especially so in Edo (Tokyo) and Osaka, where performance traditions of all sorts (drama, storytelling, and puppet plays) flourished, as did markets for handicraft items, woodblock prints, public baths, tea and wine drinking shops, and of course food.

The Gion district of Kyoto, once famous for its culture of geisha entertainers (called “geiko” in Kyoto dialect) was originally a hub for religious pilgrims seeking lodging while visiting the region’s many temples. It is still known today for its professional geisha, who apprenticed for years as maiko, rigorously learning the arts of singing, playing musical instruments, dancing, poetry, calligraphy, preparing tea, and conversation, originally to entertain merchants and other males of means. The profession is struggling to find recruits among young women today who will follow the rigorous training regimen.

Maiko (apprentice geisha) in the Gion district, Kyoto. The colorful costumes and red collars of the maiko are markedly different from those of fully trained geisha, which are more reserved. Makeup and hairstyles also clearly mark each status role. Only a few dedicated young women are training in this traditional entertainment profession today.

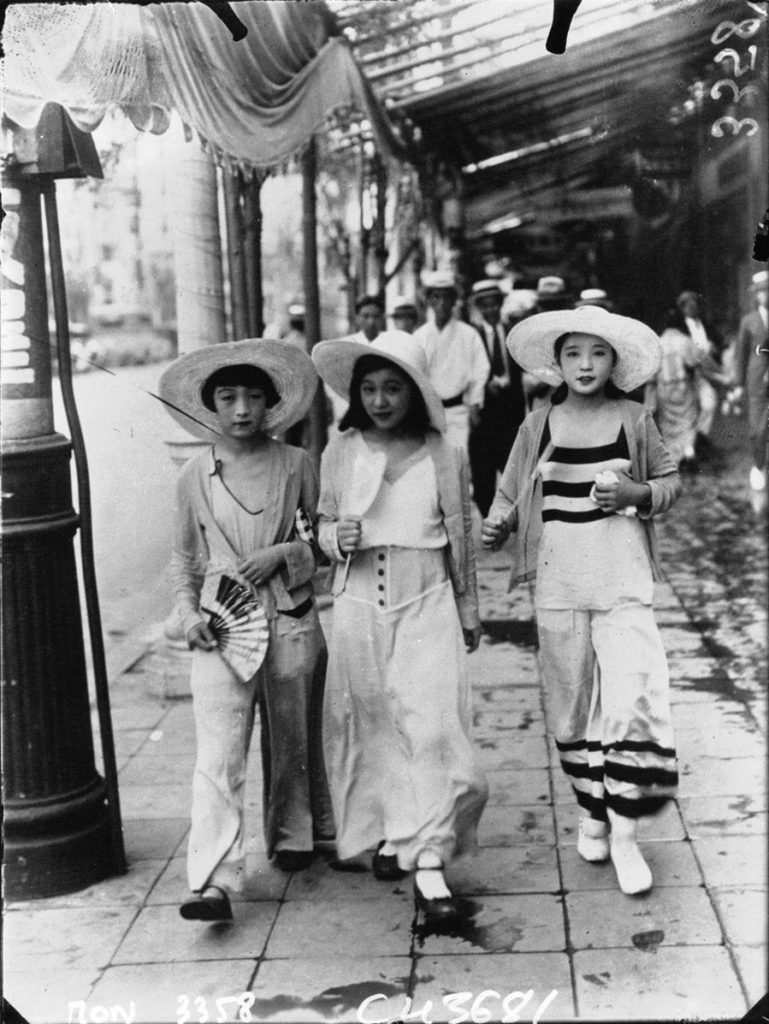

During the Meiji period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the first wave of print and film media swept Japan. By the 1920s a jazz craze hit Tokyo, and so-called mo-ga or “modern girls” imitated American flappers by wearing short skirts and fashionable hats, smoking cigarettes, and dancing the Charleston with their male cohorts.

|

|

Since the 1950s, Japan has increasingly absorbed and “remade” pop culture from the United States and Europe, expanding Japanese popular culture into every variation of rock and roll dance crazes, teen idol music, game shows, love hotels, cartoons, and so on. This dynamic of appropriation of foreign influences and re-casting within Japanese social contexts, dubbed “J-pop,” has in turn created influences on popular culture realms globally that remain strong today.

Wagakki Band (Wagakki Bando) combines rock music with traditional Japanese musical instruments and costume in their exciting, engaging stage shows. The group has toured Europe, the USA, and Asia since 2014. The performers use such instruments as a tsugaru–shamisen (three-stringed chordophone), a tsuzumi (double-headed drum), koto (stringed instrument), shakuhachi (flute), and electric guitar.

Babymetal, formed in 2010, has been described as a combination of heavy metal rock and roll plus the “cuteness” (kawaii) of Japanese “idol” culture, which focuses on teenage singers and girl groups, and the “cosplay” phenomenon discussed below. The producers claim the group members are divinely inspired by the Fox God of Japanese folk religion. Members sometimes flash the folk hand gesture for “clever foxes” (kitsune). Magical foxes are “among the supernatural creatures called yokai, also discussed below, along with the term “folkloresque”—which aptly describes Babymetal’s use of folk tradition. One of Babymetal’s songs is entitled “Megitsume,” recalling shape-shifting female foxes. Images of giant fox heads are sometimes part of the elaborate stage sets which also feature intricately choreographed lighting that compliments the unrelenting athletic movements of the performers to the beat of heavy metal music. At times, the spectacle seems to conjure the excitement of shamanistic rituals of the ancient miko shrine maidens and folk theater—resonating with the concept of “myth-ways” introduced in Module 1. A backup band of young men, garbed in freakish other-worldly garb, and called the “Kami Band” (recalling the kami nature spirits) supply the instrumentals, replete with ghoulish antics on stage. Over the years the composition of Babymetal has changed as members have moved on, but the high energy, head-banging sound of this iconic “kawaii metal” group continues. The group toured with Lady Gaga in 2014 and has opened for a number of major Western bands. A major album, entitled Metal Hammer was released in 2016 and did well on North American and European music charts.

Other hard rock, metal, and pop bands that have drawn international attention over the last two decades include The Gazette, L’Arc-en-Ciel (Laruka), Dadaroma, and most recently, Band-Maid. These and other groups often draw on eclectic aspects of Japanese popular culture, including the Visual Kei art and music movement (the latter a sort of “glam rock”), anime (cartoons), manga (comics), kawaii “cute” culture (rooted in the 1970s), Classic/Gothic Lolita costume play (inspired by Victorian-era dolls), and the maid cafe social phenomenon (cafes staffed by young women costumed as French maids).

L’Arc-en-Ciel (“Rainbow”), from Osaka, Japan, drew on a glamorous, androgynous Visual Kei-style appearance early in their career, which began in 1991, selling over 40 million records, since. In 2021 they headlined in Madison Square Gardens, New York, USA. (May S. Young, Wikipedia)

Band-Maid was created in 2013 by a former maid cafe worker, Miku Kobato. The “maid” theme in a playful parody of the “cosplay” (see below) “maid cafe” social phenomenon. The cafes are staffed by young women wearing French maid costumes who serve snacks and beverages to customers and may engage in light conversation. Originally, before the genre became more popular, customers tended to be shy young men (otaku) obsessed with online digital popular culture. Band-Maid’s bold intersection between pop music and the cosplay entertainment industry has resulted in a fast-paced, edgy mix of rock and metal music that crosses generic lines in Japanese pop culture. (Band-Maid; “Maid Cafes,” Wikipedia)

In a startling move, on April Fool’s Day 2018, Band-Maid presented themselves as “Band-Maiko,” dressing in traditional apprentice geisha (maiko) entertainer costumes. This led to an album in 2019 (pictured here) with traditional costume, instruments and lyrics in Kyoto dialect (spoken in a city still known for its once flourishing geisha culture). This attention-drawing, calculated diversifying of Band-Maid’s image is an excellent example of the intersection between layers of contemporary and traditional popular culture in East Asia. (J-pop Wiki)

Started by mixed martial artist Genki Sudo in 2014, the five member pop song group World Order amassed a huge online following with videos of robot-like, “tightly choreographed” behavior in public places, parodying stereotypes of Japanese “salary man” (sarariman), who are salaried workers known for their conformity and devoted work ethic. “Have a Nice Day,” filmed in the trendy Shibuya district of Tokyo, is one example of their parodic style. Another is “Singularity,” filmed in Nagoya, with footage of varied street life and offices. (“World Order,” Wikipedia quote; Sora News24 photo)

The global influence of Japanese popular culture has been a major force since the post-WWII era of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Pop icons from film, comic books and cartoons such as the dinosaur-like creature Godzilla and the futuristic cartoon wonder Astro Boy gained momentum in this period. In the decades that followed Ninja Turtles, Pokémon, and Tekken became the pop “folklore” for millions of children around the world.

|

|

|

|

In recent years, tremendous creativity has been expended on the production of online video gaming worlds and the fantasy worlds of comics (manga) and cartoons (anime). In a related phenomenon, the popular subculture activity known as “cosplay” (kosupure in Japanese; a short form of “costume play”) has grown since the 1980s, stimulated by costumed science fiction fans in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. In urban spaces such as Harajuku Street in Tokyo, young people meet to dress up as fantasy characters from their favorite media. It is notable that the Japanese government launched a “Cool Japan” program in the early 2000s in hopes of capitalizing on Japan’s rich popular culture as soft power on the world stage.

Harajuku District is a hotspot for fashion shops, be it mainstream, offbeat, or cosplay. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 year-old Momiji Nishiya (top) won the first ever Olympic women’s gold medal for skateboarding at the 2020/2021 Summer Olympics in Japan. This new Olympic sport is a carry-over into an official context from the popular culture street sport. Several other skate boarders from Japan won medals, including Yuto Horigome (bottom), who won the first men’s gold medal in the sport. (BBC/newsbyworld.com)

|

|

Game-ified ways of shopping populate many urban streets in major Japanese cities like Tokyo.

MEDIA CASE STUDIES

The “Korean Wave”

Since the year 2000 Korean popular culture has flooded the cultural stage of East Asia, and, increasingly the rest of the world. Known as the “Korean Wave” (or Hallyu), Korean films, music videos, soap operas, historical dramas, beauty products, celebrities and fashion have generated a buzz that draws in diverse audiences from young to middle-age, and even older. South Korean film directors, actors, musicians, and dancers have become known not only in Korea, but in Japan, China, Taiwan, throughout Southeast Asia, Northeast India, and many other places. In recent years superstar groups EXO and Blackpink dominate magazine covers, cell-phone screens, and pop music charts around the world. In terms of its impact in East Asia, some critics have suggested that the upscale, sophisticated, and sometimes blatantly materialistic image cultivated by young Korean performers directly appeals to many youths in Asia who see Korean pop culture as a comfortable, though indirect, way to engage with Western culture—and vice-versa for followers outside East Asia.

The impact of the Korean Wave on India is a growing phenomenon. The effect is especially strong in Northeast India, where much of the population have ancient roots in China and Southeast Asia. Chachui Khayi, of Tangkhul Naga ethnicity, is from the state of Manipur in Northeast India. She is the reigning Miss Spring from Ukrul district, Northeast India, selected in part for her singing and dancing skills. In 2020, she beat out 3,000 other contestants from all over India in a K-pop contest held in New Delhi as part of the worldwide Changwon K-Pop World Festival in which contestants from over 70 countries participated. In an interview on YouTube she mentioned that part of the appeal of the Korean Wave is the respect demonstrated for elders and the family in the serial dramas, values which have parallels in her culture.

Pop singers like Rain (Jung Ji-hoon) and BoA (Kwon Bo-ah; BoA is short for “Beat of Angel”) set the standard for countless new artists whose works play on a whole range of electronic mediums. Influenced strongly by pop music trends in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and more recently Japan (with its J-pop phenomena) K-pop matured by the late 1990s, in some quarters strongly under the influence of American hip-hop and Black performance artistry. Many South Korean artists flit back and forth across the Pacific between Seoul and Los Angeles, the latter city being home to the largest population of ethnic Koreans in the US. Hip-hop with a Korean attitude is performed by all boy, all girl and mixed gender groups of singers and dancers.

In the spring of 2006, Rain performed in Madison Square Garden with JY Park (a Korean pop singer who aided Rain early in his career) and American hip-pop stars such as P. Diddy. Rain has also worked with Christina Aguilera (who, incidentally, spent part of her youth in Japan). Besides music, Rain has also starred in a successful TV soap opera (called Full House) about a strong-willed pop singer who stages a sham marriage with a young Korean woman he meets by accident on a trip to China. In acknowledgment of his popularity, a top American news magazine in the early 21st century stated that Rain was the second most influential performer in the world.

|

|

BoA, with over twenty years in the industry, was discovered at age eleven while attending an audition for her older brother. Media moguls spotted her talent and, following the model of “idol” creation perfected in Japan, she was subsequently trained and packaged to become a pop singer and dancer for the target markets of Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. A polyglot, BoA speaks not only Korean, but Japanese, English, and reportedly, Chinese with an eye on the growing Chinese market that for the moment is enamored with the style and “cool” of all things Korean. As of 2006, she had released 9 albums (several in Japan)’ and was still landing solid contracts in 2020.

|

|

In 2009, The Wonder Girls’ single “Nobody” was listed in Billboard top 100 in the USA. The group, produced by JYP entertainment, had a retro-1960s/1970s vibe, influenced by Black singers such as Diana Ross and the Supremes.

|

|

Another retro-1950s/1960s South Korean girl group who have toured Europe and the USA is The Barberettes 바버렛츠 (right), formed in 2014. They perform songs such as “Be My Baby,” recorded by the Ronettes in 1963.

The Ronettes (left), were a girl group (two sisters and a cousin)of the 1960s and 1970s from Spanish Harlem, New York, and whose backgrounds included African-American, Cherokee, Irish, Puerto Rican, and Chinese heritage. In 1964, on their first London tour, they met up with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

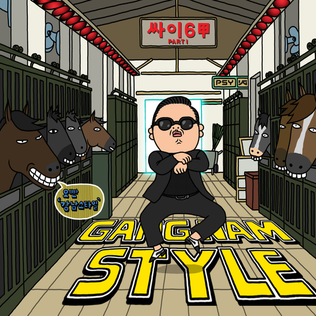

Psy became a global legend with the release of the catchy and irreverent “Gangnam Style,” gently mocking the lives of the nouveau riche in the trendy Gangnam district of Seoul. Versions of the dance mutated endlessly worldwide. In 2012, the song became the first music video to reach 1 billion on YouTube. As of 2023, it has over 4.8 billion views, though it is now only the 11th most-watched video of all time. (Wikipedia)

Since their debut album was released in 2016, K-pop girl group Blackpink has become one of the most popular girl groups in the world, with record-breaking numbers of subscribers on YouTube and an enormous social media following worldwide. The group has been listed on both the U.S. and UK billboard charts and garnered awards around the world. In the past few years, they have collaborated with artists like Selena Gomez, Dua Lipa and Lady Gaga. Blackpink’s members, including two South Koreans, a Korean New Zealander and a Thai, also reflects the pan-Asian/international nature of K-pop, and its increasingly global reach.

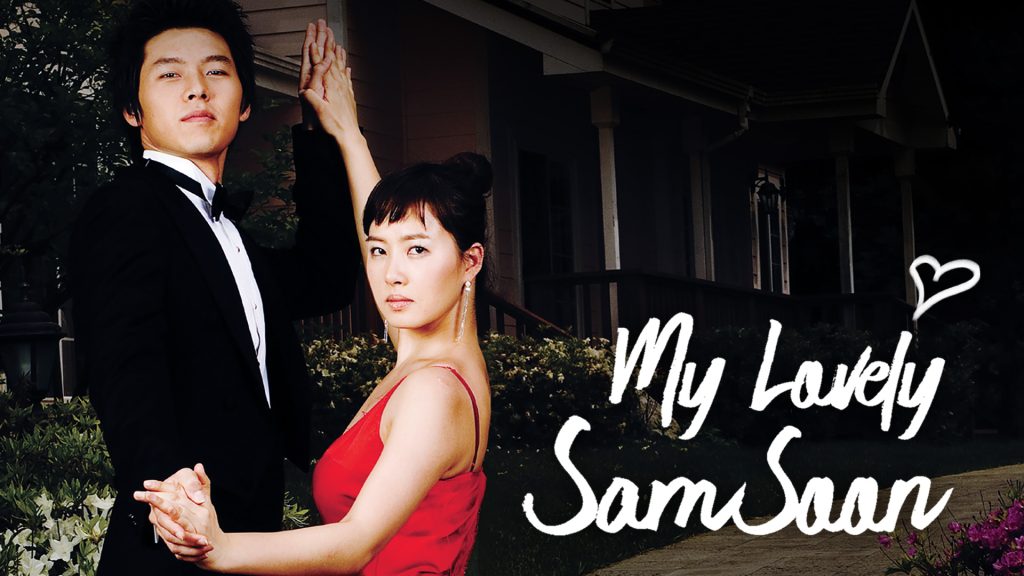

Over the last two decades, gripping Korean soap operas become known for tear-jerking drama, sometimes earthy humor, and urbane sophistication with compellingly intricate plots on real-life themes. They also combine emotionally-resonant music and visually stimulating cinematography. Among the most popular have been the love story Winter Sonata (which gained near cult-status among women between 30-50 in Japan), the humorous urban white collar drama All About Eve, appealing to 20- to 30-somethings in Korea, and My Lovely Sam Soon, following the misadventures of a somewhat plain, twenty-nine-year-old unmarried woman in a contemporary urban setting.

A true phenomenon is the 45-episode historical drama Jewel in the Palace (Dae Jang Geum, literally, “The Great Jang-geum”) which in 2003-2004 drew a massive following all over East Asia and has been shown on cable in the US. Set in the 18th century, it is the story of a young woman, Jang Geum (played by Lee Young-ae) whose mother was driven from her position as head of the king’s kitchen by the evil plotting of jealous palace ladies. Her mother succumbs to the hardships of the road and Jang Geum later makes her way to Jeju Island, where she trains as a traditional doctor. She then passes the medical exams and is assigned in the King’s palace. Drawing on her previous cooking knowledge, her doctor’s training, and her alliances with persons in power, she single-mindedly clears her mother’s name while managing to survive a host of plots hatched by scheming palace officials and ladies. She is at one point given the unheard-of honor of being the King’s personal physician and aids in discovering the cause of a killing epidemic. Along the way she captures the fancy of handsome, upright young official (played by Ji Jin-hee), and despite many obstacles the couple eventually marries. The drama, based on a true story adapted by Kim Yeong-hyeon, features incredibly detailed costumes and settings that include many of the traditional Korean foods described elsewhere in this course. The lead actress and actor have both become media phenomena in their own rights and the drama’s set has become a major tourist attraction. Such period serial dramas are now made and promoted elsewhere in Asia, including China, with its controversial block-buster series about the life of imperial women depicted in Story of Yanxi Palace (2018).

Another important aspect of the Korean Wave is the emergence of world class Korean directors. Korean film began in the early 20th century. The first talking picture was a traditional love story, produced in 1935, entitled Ch’unhyang-jun (The Story of Ch’unhyang). Due to periods of chaos and disruption, few films survive from the period before the Korean War (1950-1953). Korean filmmaking, however, enjoyed a renaissance and “golden age” in the later 1950s and 1960s, though the widening of TV audiences and the importation of Hollywood films affected the market for home-grown films in the 1970s and 1980s.

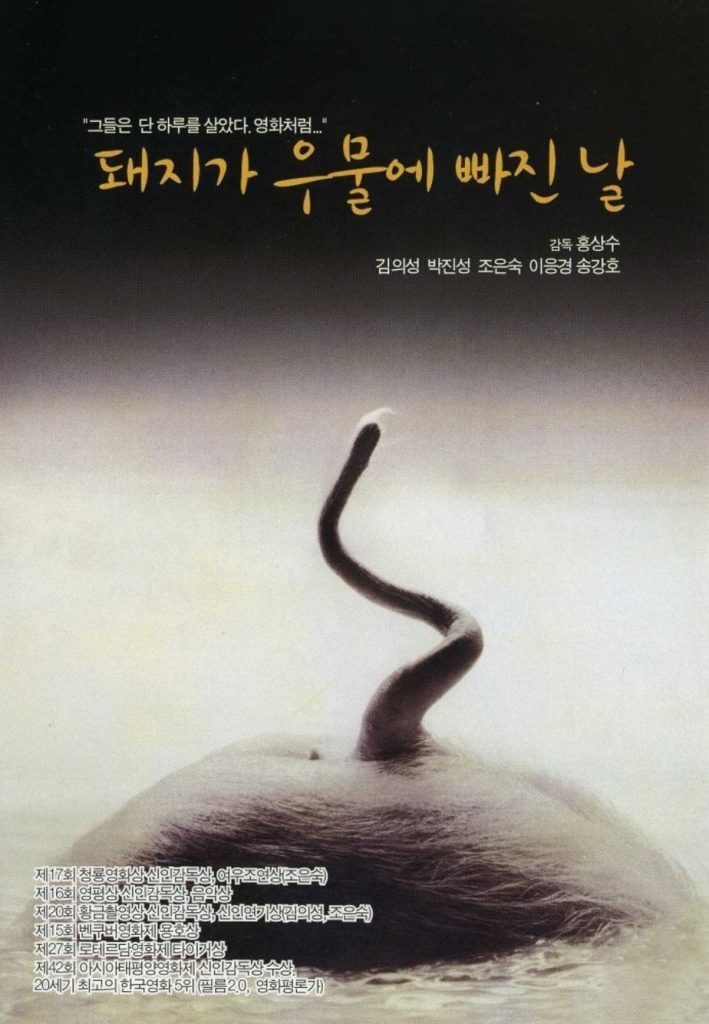

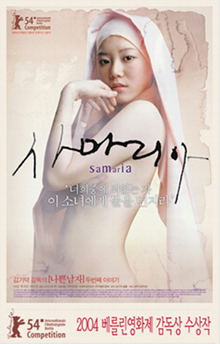

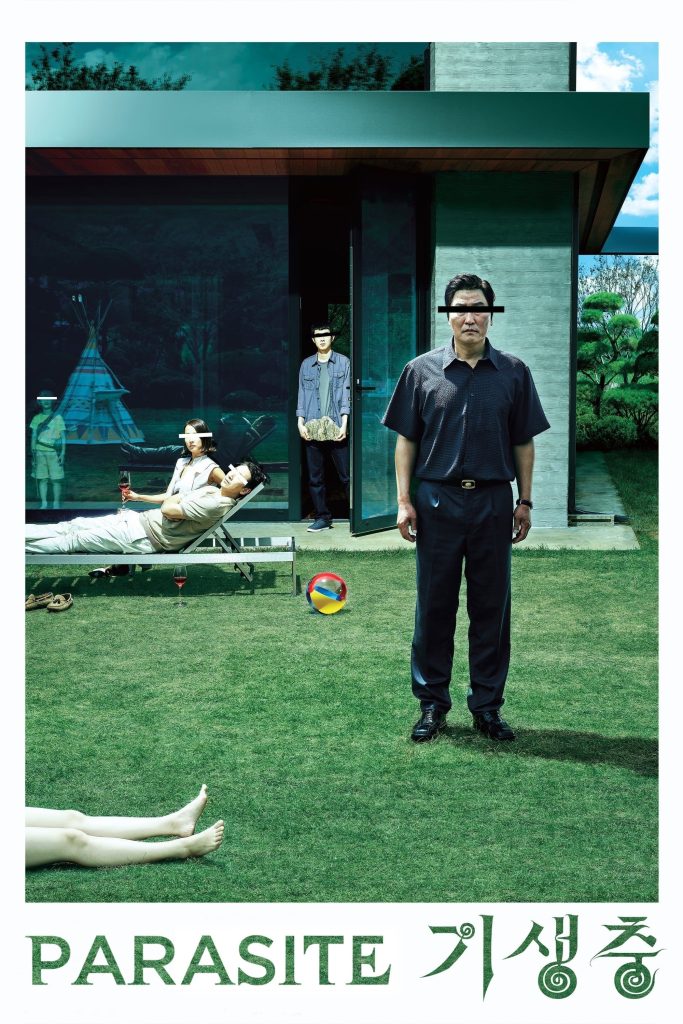

Since the late 1990s, new generations of directors have appeared, producing engaging and sometimes highly acclaimed (and sometimes controversial) films such as The Day a Pig Fell into the Well (Hong Sang-soo, 1996), The Contact (Chang Yoon-hyun, 1997), The Isle and Samaria (Kim Ki-duk, 2000 and 2004) and Oasis (Lee Chang-dong, 2002). Aside from these more serious works, in recent years, a strong popular film market has developed. Among the titles for 2006 that humorously explore issues of gender and sex in today’s South Korea, were My Scary Girl by Son Jae-gon, Desopo Naughty Girls, by E J-yong, and Lee Hae-yong and Lee Hae-joon’s Like a Virgin (Cheonhajangsa Madonna)—the latter is about a young male protagonist who dresses like a young woman, falls in love with a male Japanese teacher, and ends up on the school Korean wrestling team. In 2020 Bong Joon-ho’s biting thriller Parasite (2019) became the first non-English language film to win the United State’s Academy Award for Best Picture.

|

|

|

Early Chinese Pop Music and Contemporary Film

Music

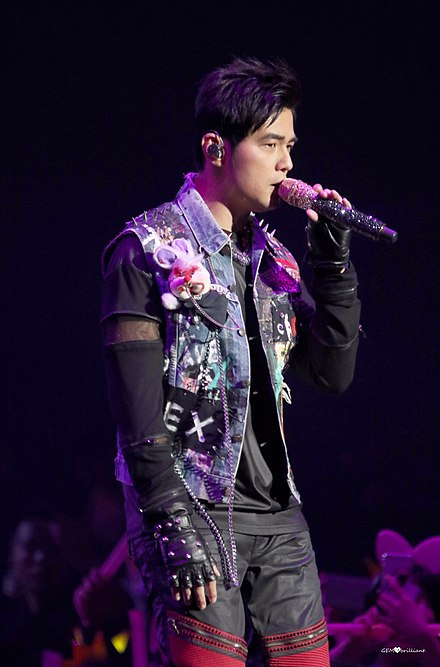

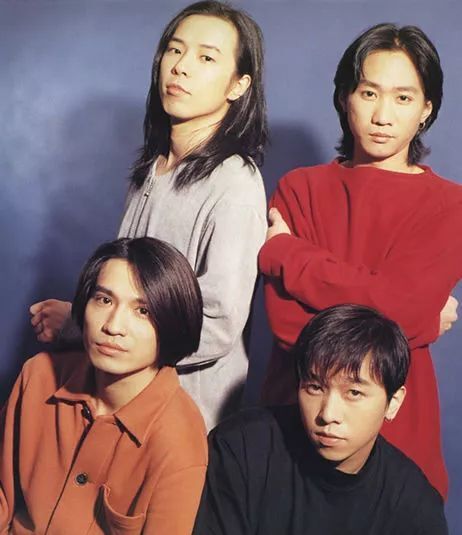

Rock singers like Cui Jian and bands like Tang Chao (Tang Dynasty) and Heibao (Black Leopard) emerged in the mid to late 1980s, influenced by Western rock bands and the success of pop singers such as Deng Lijun (Teresa Teng) in Taiwan and others in Hong Kong that rose to fame on the karaoke craze that swept East Asia in the 1980s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The early Mainland rock sounds appealed to a somewhat rebellious generation of urban “hooligans” (liumang) that reflected the profound and often unsettling social shifts in China between the end of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1970s and into the early 1980s, an era of greater openness and market experimentation. By the mid-1990s a phenomenon called dakou (cut CDs), in which intentionally damaged CDs (seconds, non-releases, and overstocks) were dumped on the Chinese market by Western companies and sold at a fraction of the original cost, along with pirated CDs, created a new interest in rock music. Groups sometimes made their own recordings and distribute them outside official channels. Among these trends emerged a less rebellious and diverse mix of popular, underground, and folksy bands that included Qingxing (Sober), Supermarket, New Pants, NO, Tongue, and urban folksinger Hu Mage. The mix also included successful ethnic minority bands such as Mountain Eagle (Yi rockers from Sichuan) and Red Plateau from Tibet.

In the summer of 2005, a television station in Hunan province organized a nation-wide amateur “Super Girl” singing contest, sponsored by the Mongolian Cow Yogurt Company. Millions of viewers voted by cell-phone, prompting some Western and Hong Kong reporters to see the event as an experiment in national democracy. The winner, Li Yuchun, from the Sichuan Music Academy, appeared on the cover of the international version of the popular U.S. news magazine Time.

Film

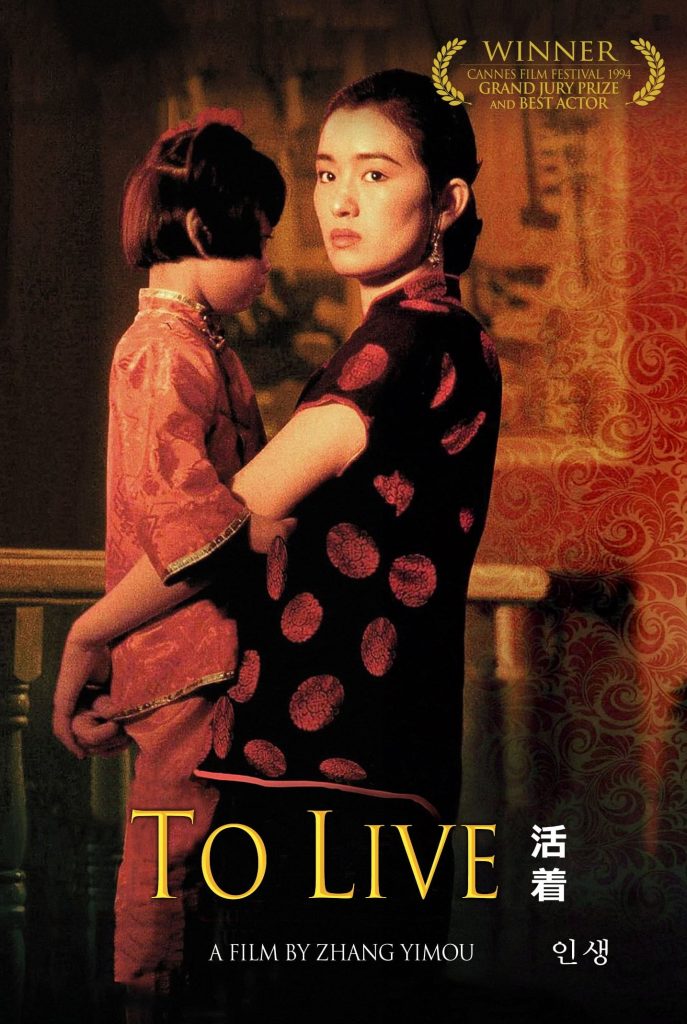

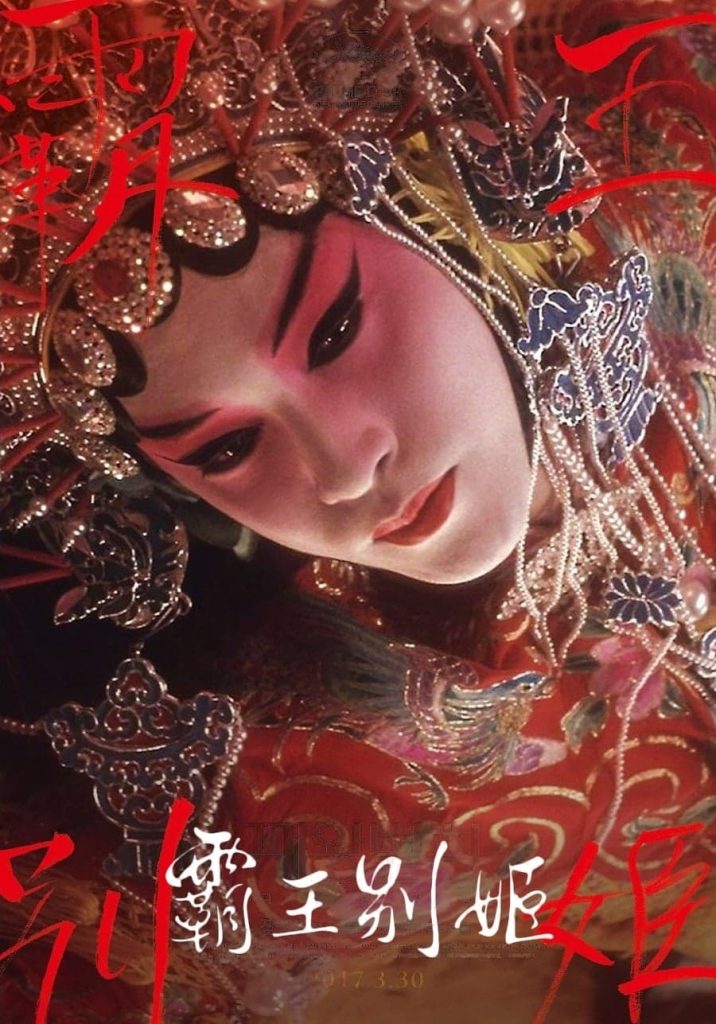

Foremost among the developers of contemporary mainland Chinese film since the end of the Cultural Revolution are the Fifth Generation directors Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige, who were strongly influenced by Italian and American cinematography and films. Both emerged in the mid-1980s with films like Red Sorghum and Yellow Earth. The term “Fifth Generation” refers to their generational order in the history of Chinese film, which grew up in the early 20th century mainly in Shanghai and developed under the dual influences of Hollywood and Soviet propaganda films in the ensuing decades.

|

|

|

|

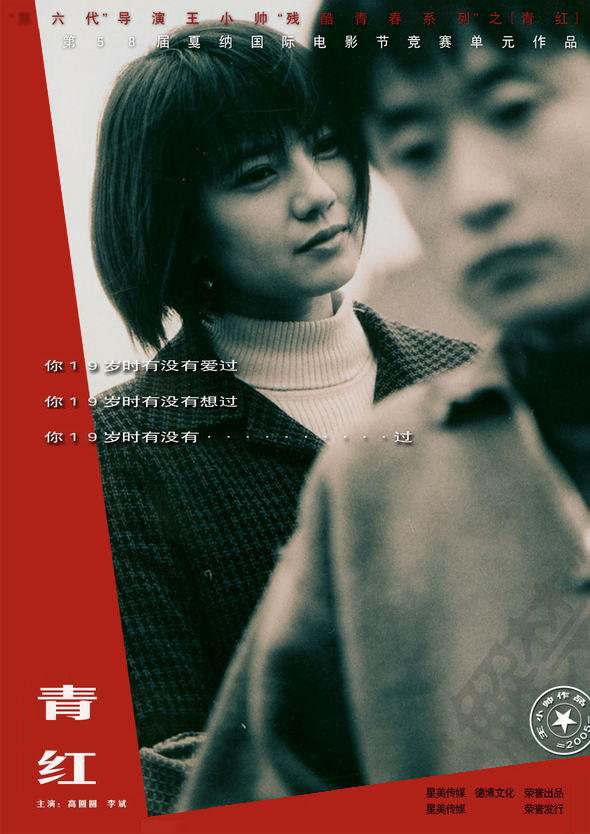

In the early 2000’s, a number of younger directors, who are loosely referred to as the Sixth Generation by film critics but actually have very different and individualistic film styles, were garnering increasing attention both in and outside China. A lot of their films are very edgy and bring a poignant criticism to contemporary life in China. These include Wang Xiaoshui’s Beijing Bicycle (2001) and Shanghai Dreams (2005), Jia Zhangke’s Platform (2000) and The World (2004), and Lou Ye’s Suzhou River (2000).

|

|

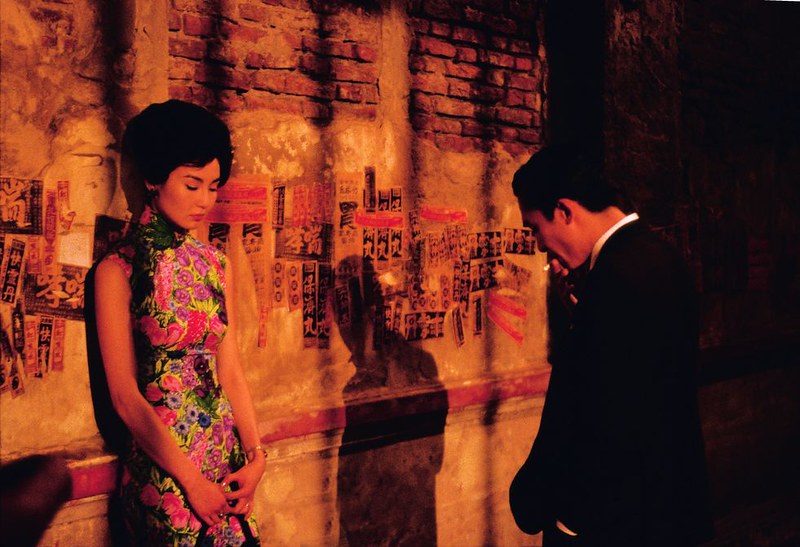

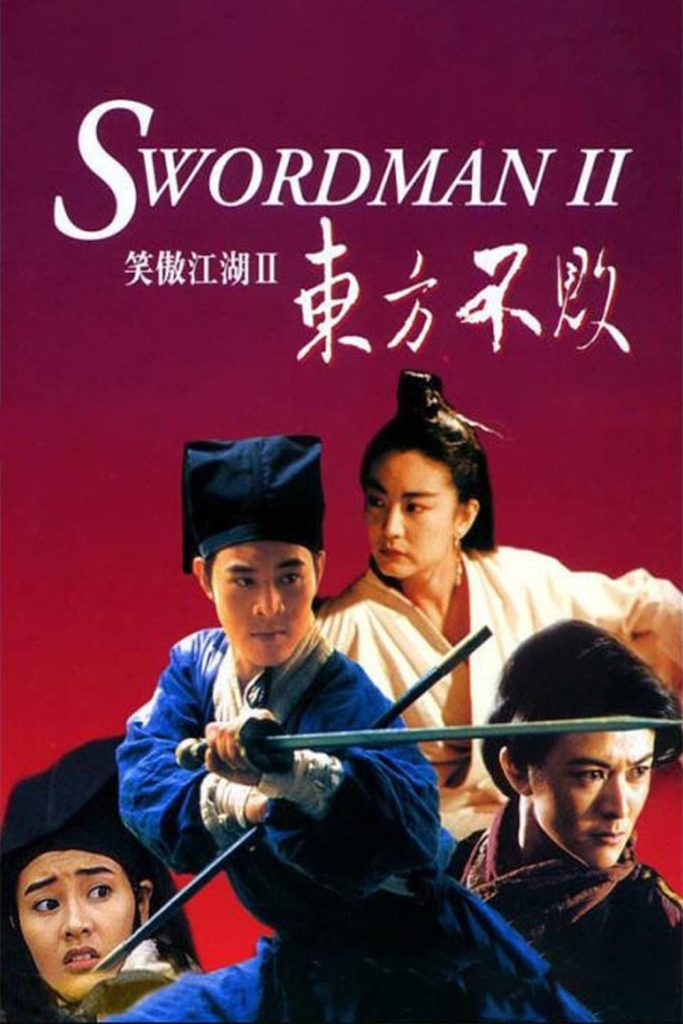

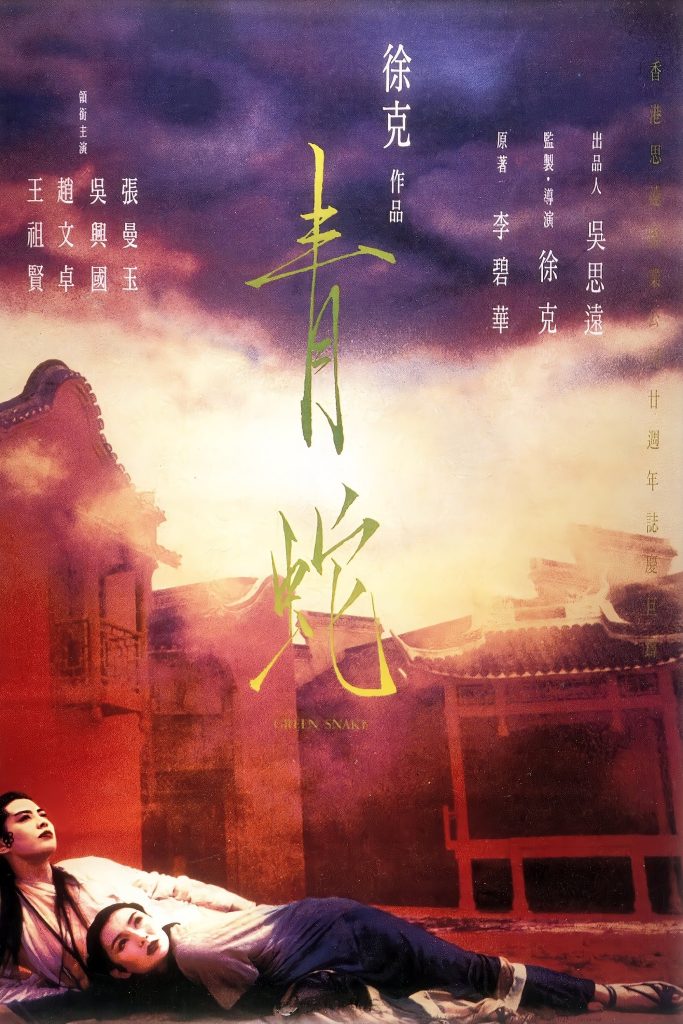

Beginning in the late 1950s, film markets in Hong Kong and Taiwan grew. A huge number of martial arts films with stars that included the incomparable martial artist and actor Bruce Lee were produced in Hong Kong in the next decades. Acclaimed films from the 1990s and 2000s by Taiwanese filmmakers, and those working in and producing films for the wider Chinese-speaking diaspora include Eat Drink Man Woman (1994); Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) by Ang Lee, a Taiwanese director based in the US; and the influential films of Hong Kong’s Wong Kar-Wai including Chungking Express (1994), In the Mood for Love (2000), and 2046 (2004). Tsui Hark is another highly-influential Hong Kong director and is famous for his martial art and action films such as Swordsman (1990) and its sequels, Once Upon a Time in China (1991) and its sequels, Time and Tide (2000), and Seven Swords (2005).

|

|

The fight scene in the bamboo forest (left) in Taiwanese director Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) has become a classic. Actors Chow Yun-fat and Zhang Ziyi battled on stalks of bamboo. Zhang Ziyi (right) rose to international fame in this film and director Zhang Yimou’s House of Flying Daggers (2005). She has since starred in numerous films, a historical drama, and most recently a remake of the Japanese film classic, Godzilla. This photo is dated 2019. |

|

|

|

|

Chinese actors such as Jackie Chan, Jet Lee, Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, Chow Yun-Fat, Maggie Cheung, Gong Li and Zhang Ziyi have become household names in many places around the globe.

Jet Li’s first credited film role was in 1982’s Shaolin Temple, which was the first martial-arts film filmed in Mainland China, and one of the first Hong Kong-Mainland co-productions.

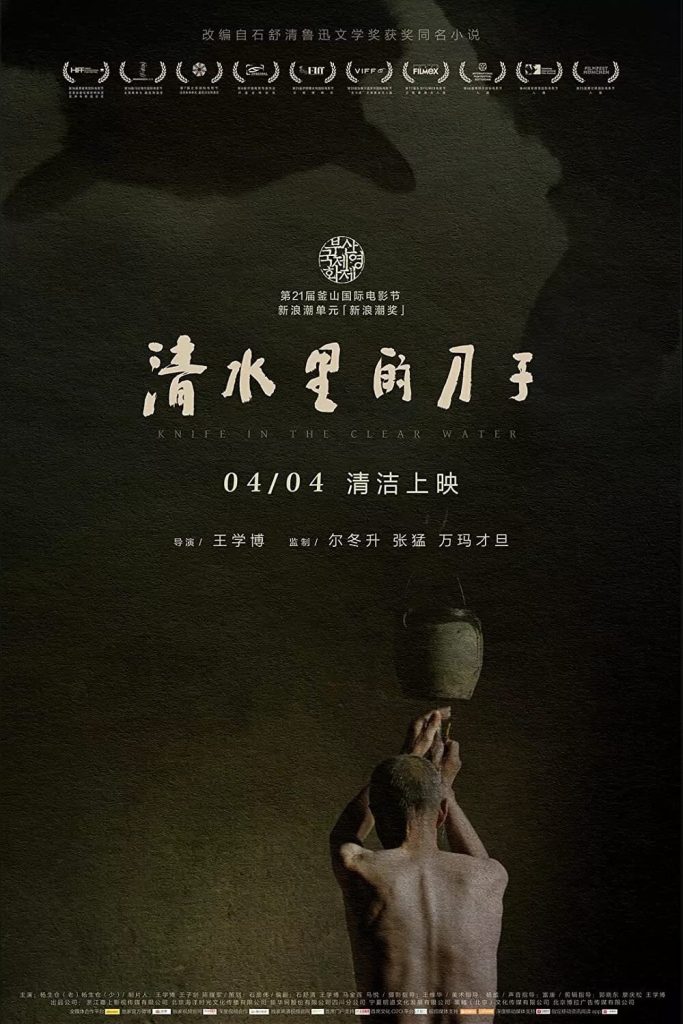

In recent years a few production companies have produced well-received films highlighting the lives of people groups populating the geographical borderlands of China.

Knife in the Clear Water is a 2016 film directed by Wang Xuebo concerning life in a remote Hui Muslim community in Northwest China. It won awards at several international film festivals. The plot revolves around an elderly man who is pressured by family members to sacrifice a prize bull in the wake of his wife’s passing. Like other films depicting China’s border areas, human activity is set in sublime landscapes. |

|

|

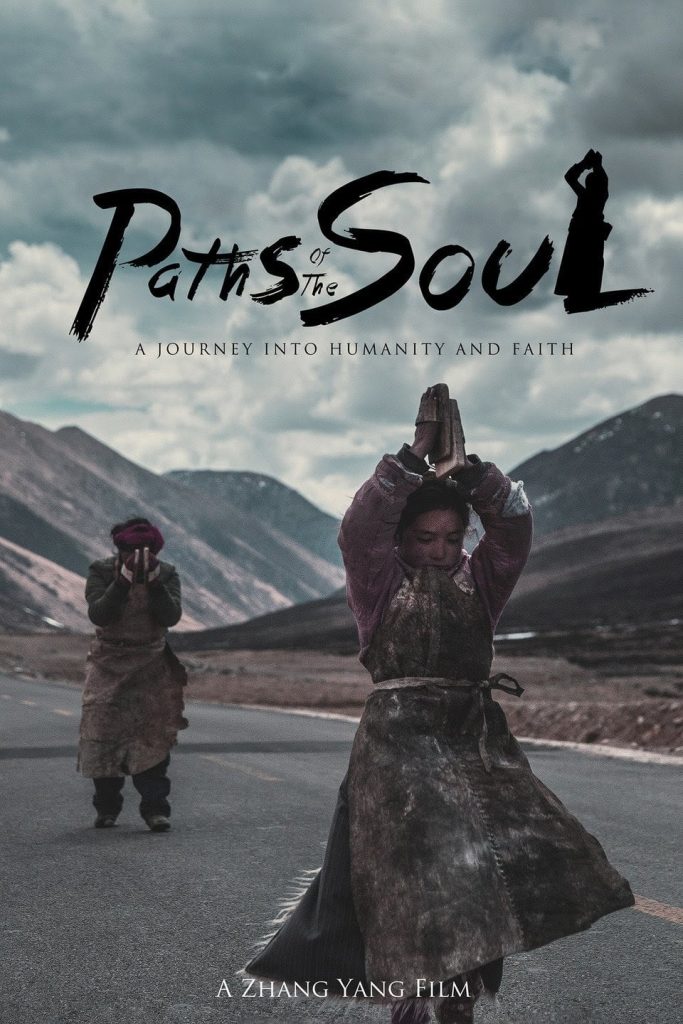

Paths of the Soul is a 2015 low-budget film directed by Zhang Yang and featuring everyday Tibetans walking on a 1,200 mile pilgrimage to sacred Mt. Kailash. None of the people in the film were actors, and there was no script. The film earned over 40 million yuan in its first 11 days in theaters. |

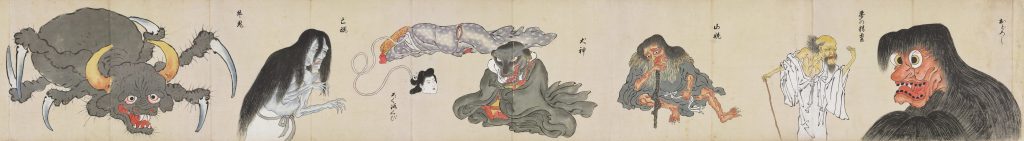

Mountain Witch: Yokai Monsters in Japanese Pop Culture

Japan has a rich tradition of various mysterious supernatural beings called “Yokai,” a word sometimes translated as “demon” or “monster” and borrowed from the Chinese yaogui centuries ago. There are hundreds of different yokai that appear in various forms, exhibit various traits (mischievous to monstrous) and reside in places ranging from the domestic to the wild, including streams, trees, mountains, and seas. Many richly illustrated accounts of the yokai survive from the Edo period and the monsters have been the subject of many paintings and illustrations. Pioneering Japanese folklorist Yanagita Kunio collected many stories about yokai told orally in the village of Tono in northern Japan, stimulating large scale collection efforts all over the country that resulted in numerous collected stories. Some of the more famous yokai include kappa, which look like a cross between a salamander and a turtle and seem to have inspired the famous Ninja Turtles of pop culture, the tsuchigumo spider woman, and an anthropomorph with birdlike features called tengu. The monstrous oni, human in form but often with bizarre hair, horns, color, and gnashing teeth suitable for eating humans, has been re-cast in many forms in contemporary films, digital games, and manga in a manner that yokai expert Prof. Michael Dylan Foster describes as “folkloresque”—a phenomena that draws on an earlier folk form, but is translated into a new context of meaning, sometimes only an essence or inspiration. Foster’s books Pandemonium and Parade and The Book of Yokai, describe many of the traditional yokai and their current incarnations in pop culture. The persistence of yokai today may be linked to how certain anxieties of modern life can be expressed and mitigated by the supernatural beings, a function that may be rooted in prior ages.

|

|

Yokai expert and folklorist Michael Dylan Foster, UC Davis, and his book “The Book of Yokai.” |

|

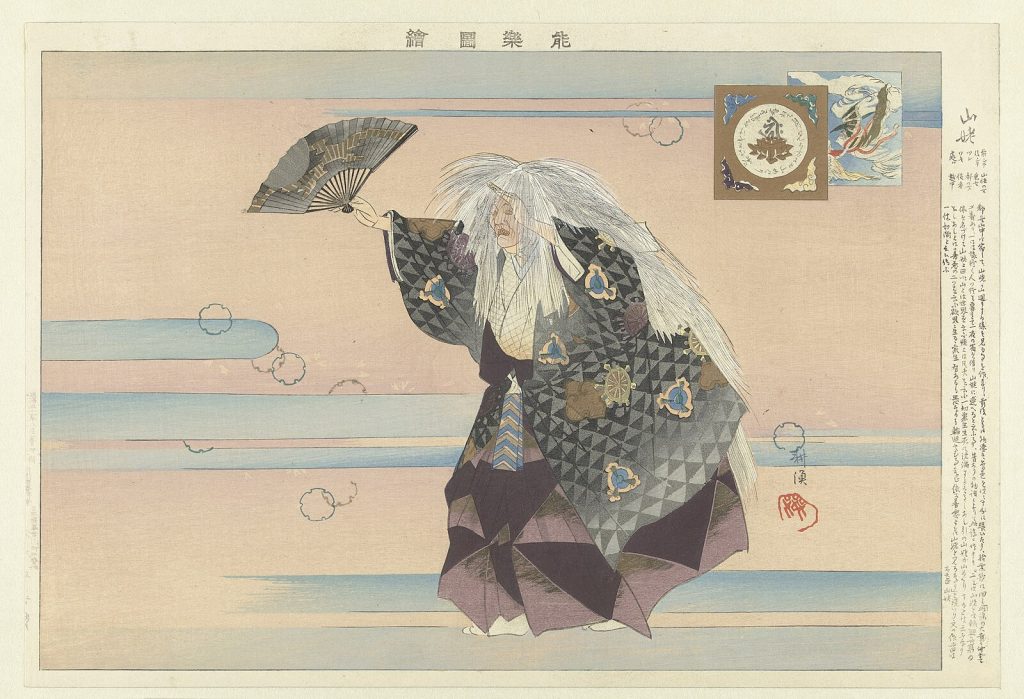

A subset of oni are the female “mountain witches” known as yamauba or yamanba. The mountain witches may appear as voluptuous younger women, or more typically as ancient hags. The creatures are know for their cannibalistic ways, though at least one had a prized “golden son” Kitaro, who figures in many stories. According to yokai expert Prof. Noriko Tsunoda Reider (a graduate of the East Asian department at Ohio State), the yamauba have been revived in contemporary pop culture, though the creatures have a long history of being represented in various media, such as traditional Noh theater. For instance, in 1999-2000, at a department store in Shibuya district, Tokyo, a number of young women arrayed themselves in extreme costumes and makeup, earning themselves the name yamanba-gyaru (“Mountain Witch Girls”). Other representations have appeared in manga, anime, films, and gaming, such as Hayao Miyazaki’s 2001 anime film Spirited Away, in which the old female bathhouse keeper Yubaba has some traits similar to mountain witches.

Discussing the social meaning of contemporary Yamauba (and yokai in genral) in popular culture, Reider notes that while the activities of the mountain witch girls are group-oriented and involve display, friendship building, and passive rebellion, the traditional yamauba, “lives independently and does not need human companionship, although she may enjoy human company now and then. The vicious yamauba who eat human flesh do not attack humans just for fun; they attack because they need something to eat or the humans have encroached on the territories” (Reider 2021:145). Thus, the meaning of the “yamauba-esque” costumes and other expressions in contemporary society form within new contexts and create new facets of mountain witch traditions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Japan’s most famous monster? The 1954 film Godzillareflected Japanese anxieties over the Post WWII society. The film became an international cult classic. Although not a “traditional” Japanese yokai the creature holds many similarities to monsters in the genre.

Republic of Mongolia and Inner Mongolia: Heavy Metal and Folk Punk

The Hu broke onto the heavy metal scene in 2016. One of their world tours included a gig in Columbus, Ohio. Conveying the spirit of the open steppe, The Hu trace their name back to the “Huns” (Hunna) who were precursors of the Mongols and included groups such as the Xiongnu. Contemporary Mongolia, lying on the northern border of China, has a lively pop music and film scene. The group includes indigenous “throat singing” and instruments like electrified horse-head fiddles (morin khuur). The Hu are one of several successful Mongolian heavy meatal bands. Hit songs include “Wolf Totem” and “Yuve, Yuve, Yu.”

Hanggai, a multi-cultural rock group mixing traditional and punk themes was founded in Beijing, China, in 2004 by Inner Mongolian and Han musicians. A 2016 album Horse of Colors features grassland themes that permeate their music. The group sings in both Mongolian and Chinese.

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

- Japan

- Yokai 101 – Yokai expert Michael Dylan Foster gave a virtual lesson on the basics of yokai in 2021 for the Japan Society of Northern California.

- Japanese Commercials – This YouTube channel has been posting compilations of Japanese advertisements since 2019

- Chicano/ Chicana Culture in Japan – A fascinating New York Times feature on the chicano subculture in Japan

- Chola Culture in Japan – Another fascinating video about a subculture in Japan that complicates the discourse about “cultural appropriation” that carries much weight in the U.S.

- Wagakki Band – A 2020 live performance of the song Senbonzakura by Wagakki Band

- “Have a Nice Day” – A music video of one of the musical group World Order’s most famous songs

- China

- Long-spout Tea Pouring – A Great Big Story video about the art of long-spout tea pouring

- Livestream Shopping – A BEME News feature about the burgeoning e-commerce live-streaming world in China

- The “3-second” E-commerce Live-streamer – China Insider analyst David Zhang discusses the unique techniques of e-commerce live-streamer Zheng Xiangxiang and how she fits into the booming world of Chinese e-commerce live-streaming

- Li Ziqi Interview – Goldthread producer Venus Wu interviews online influencer Li Ziqi about her videos and perspectives

- The Shaw Brothers – A short video essay on the history of Hong Kong’s biggest film producers

- Zhang Yang’s Paths to the Soul – An article written for The Ohio State University’s MCLC that discusses the surprising success of this documentary about a remarkable Tibetan Buddhist ritual

- North and South Korea

- The South Korean Entertainment Phenomenon – A CBC News video reporting on how South Korea became the video entertainment juggernaut it is today

- Korean Wave – A new report expanding on the nature of the Korean Wave

- K-Pop Trainee Visa – A news report explaining how South Korea has begun to offer a visa for those interested in gaining the same musical training as K-Pop stars

- New Jeans at Busan National University – A fan recording of New Jeans (billing themselves as the “new genes” of South Korean pop music) performing their song “How Sweet” at Busan National University in May, 2024.

- Waacking Dancer Lip J – Lip J (Hyowon Cho) is a highly accomplished waacking dancer from South Korea. Her art form combines traditional Korean dance moves with popular dance and music from the West.

- The Story of Arirang – A video introducing Korea’s most famous song.

- “Friendly Father” – A propaganda music video by North Korea that went viral on TikTok in May 2024