2 Timeline East Asia

📍Make sure to check the Additional Media Playlist at the end of the Module. Many videos or articles will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

OUTLINE

INTRODUCTION

Before beginning the more in-depth overviews of the history of East Asia in Module 2, this section presents a basic timeline of eras that supersede the timeline of any of the three areas and divides the history of East Asia into seven distinct, but sometimes overlapping eras that often involve other parts of the world. This demarcation will provide a framework in which to address larger historical issues and trends that impact the cultural regions of China, Korea, and Japan in their own ways.

| (1) Prehistory to the Neolithic Era, represented here by a Neolithic jade disk, or bi of the Liangzhu culture, c. 2500 BCE, from present day Jiangsu province, China. |

|

| (2) The Early Kingdoms Era, represented here by a rectangular ritual food vessel, elaborately cast in bronze with zoomorphic motifs from the late Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BCE), Anyang, China. |

|

| (3) The Silk Road Era, represented here by the image of the Buddhist deity Virupaksa on a silk banner, preserved in Cave 17 of the Dunhuang Caves, Gansu province, China, on the Silk Road. The image shows the convergence of cultures, religions, and technologies in the era. (It was collected in the early 20th century by the British explorer Aurel Stein.) |

|

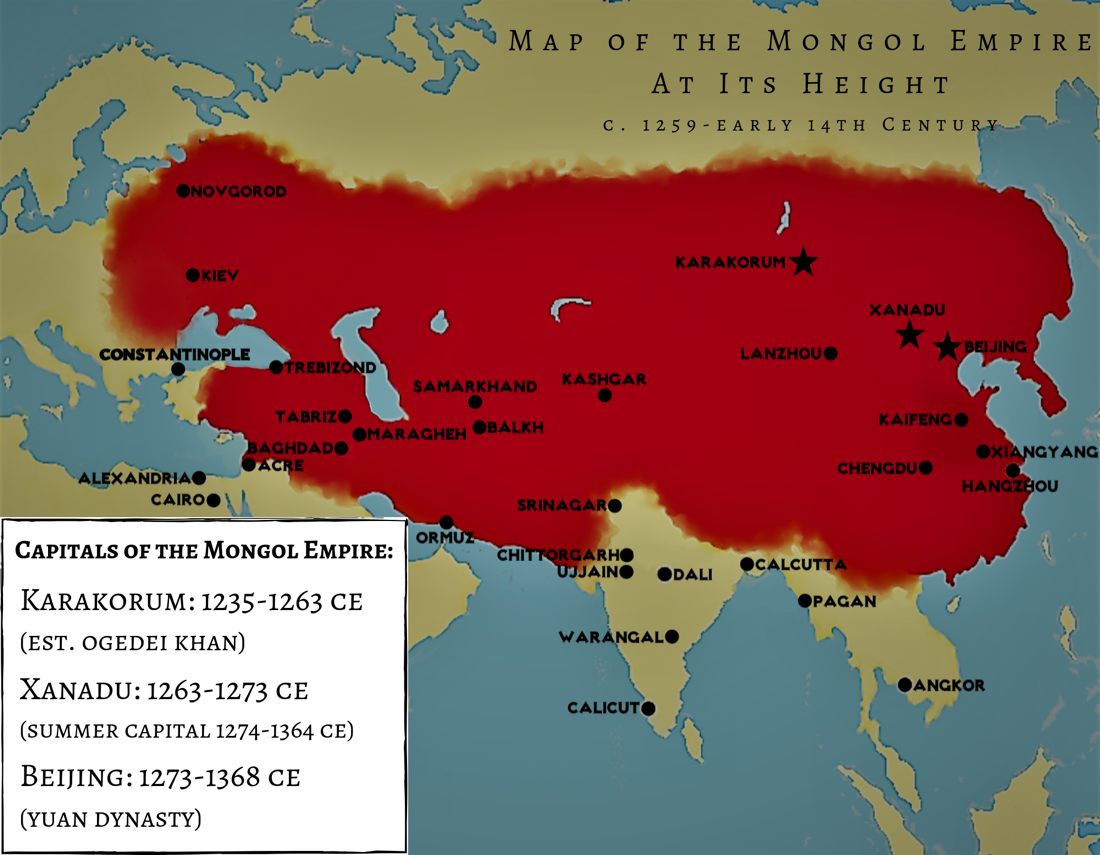

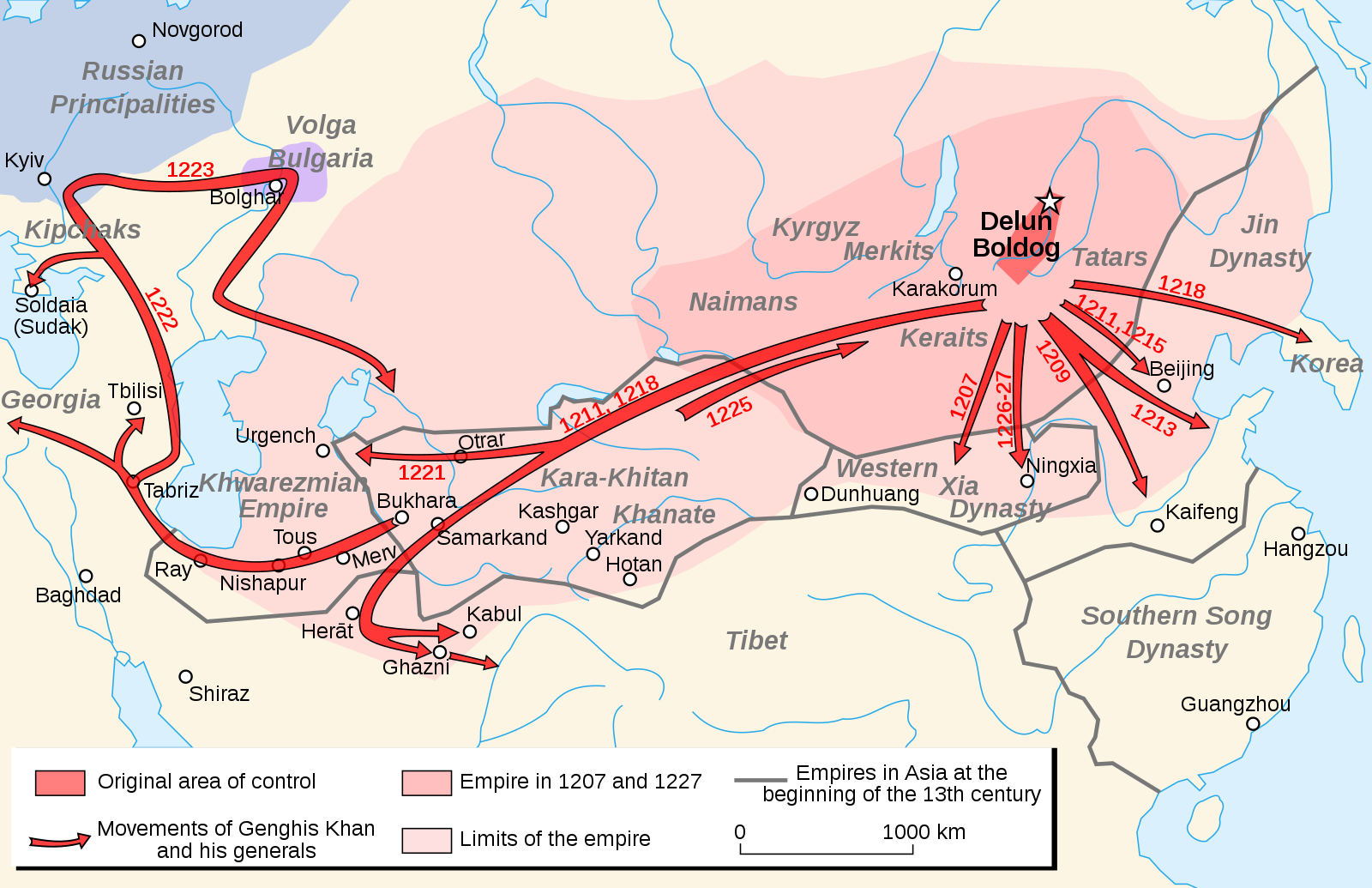

| (4) The Mongol Empire Era, represented here by a map of this vast Empire at its height, c. 1259. |

|

| (5) Mercantile Cultures Era, represented here by the Gyeongbok Palace of the Joseon Dynasty, built in 1395 and now located at the heart of Seoul, on of East Asia’s urban cultures. |

|

| (6) The Era of Imperialism, represented here by a portrait of Mutsuhito, the Meiji Emperor, 1873, who oversaw Japan’s opening to the Imperialist West and transformation into an imperial power itself. This is among the first photographs of a Japanese emperor. |

|

| (7) The Post-WWII to 21st Century Era in East Asia, represented here by the skyline of contemporary Shanghai, transformed from an early Chinese treaty port to the birthplace of Chinese modern culture, and then to one of the world’s largest and most cosmopolitan cities. |

|

BRIEF OVERVIEW OF EACH ERA

1. PREHISTORY TO THE NEOLITHIC (prehistory + 10,000-1600 BCE)

The earliest human inhabitants of what we now call East Asia included the famous “Peking Man” (Homo erectus) and similar early humans in southwest China who date to nearly one million years ago, as well as evidence of a number of other early hominids.

“Peking Man” is the name associated with the bones of an extinct hominid discovered in 1927 inside a cave at Zhoukoudian near Beijing, China. Objects discovered include 14 partial craniums, 11 lower jaws, many teeth, some skeletal bones and large numbers of flaked stone tools. The age of these objects have been estimated to be between 500,000 and 300,000 years old. As a form of Homo erectus, scientists regard Peking Man as one of several early hominids whose remains have been found in East Asia.

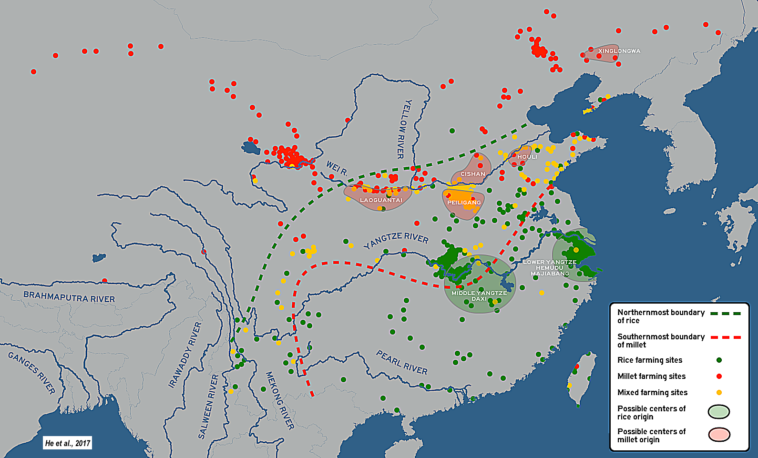

The Neolithic Period began around 10,000 BCE in the Middle East. It was the era in which farming and the domestication of animals began, marking a widespread transition from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural cultures. It is thought to have begun in the area we now call East Asia in China, around 9500 BCE.

Thus our story picks up some ten thousand years ago, when village culture, animal husbandry and agriculture were beginning to spread throughout East Asia.

This was a time before kingdoms or countries.

Advanced polished stone tools were still in wide use; thus the name Neolithic, or New Stone Age.

Many small local cultures formed and adapted their cultures to various geographical conditions all across the region. Populations were especially concentrated along rich river valleys and lower, coastal areas. As the last period of the Stone Age, the Neolithic ended with the beginning of the use of metal tools in the Bronze, Copper or Iron Age according to region.

|

|

Archaeologists have discovered pottery in Japan that dates to 8,000 BCE—the world’s oldest on record. On the continent, pottery production dates to at least as early as 5,000 BCE. Yangshao culture was a Yellow river Neolithic culture that cultivated millet and rice and produced painted pottery with human facial, animal and geometric designs.

The Jomon Period (c. 12,000 – 300 BCE) is named for the cord-marked patterns found on much of the pottery produced during this time in what is now Japan. Judging from the burn marks along the sides, Jomon pottery must have been planted firmly into soft earth or sand, then used for cooking. It is thought that Jomon pottery was made by women, as was the practice in most early societies, especially before the use of the potter’s wheel.

The Jomon also fashioned small human effigy figures, called dogu.

Dogu depict human figures, but always distorted into fantastic shapes, usually with oversized heads, small arms and compact bodies. The marks on the shoulders and neck of this figure indicate tattooing. The purpose of dogu is unclear, but many scholars believe that they were used in a kind of sympathetic magic wherein the illness or misfortune of the owner could be transferred to the dogu, which would then be broken to cure the illness or dispel the bad luck. This theory is supported by the fact that most of the dogu figures that have been found appear to have been deliberately broken.

2. EARLY KINGDOMS (1600 BCE- 600 CE)

Early Kingdoms and Empires in China

Shang (1600-1100 BCE): Yellow River, kingdoms, writing (oracle bones), bronze

Zhou (1100-221 BCE): feudal state, cast iron, philosophies: Confucianism and Taoism (Daoism)

Qin (221-207 BCE): first centralized empire; Emperor Qinshi Huangdi; terra-cotta warriors

Over time, kingdoms emerged in East Asia, the oldest along the once heavily forested Yellow River of northern China.

The Shang Dynasty

The first historical kingdom in this area was called the Shang Dynasty (1600-1100 BCE), though Shang written records tell of an earlier dynasty known as Xia. Shang ruled through a small number of aristocratic families who lived in walled urban complexes and who were buried in large underground tombs. The common people, who were farmers and craftsmen, lived in villages and were subject to the rule of the all-powerful elite. Many of the commoners also served in the huge Shang armies. The development of regional kingdoms with class divisions, the invention of writing, and the sophisticated use of bronze for casting weapons and ritual vessels are characteristic of the age. Here we see Shang bronze tripod or ding a cauldron standing upon legs with two facing handles, used for cooking, storage and ritual offerings to gods or ancestors. And on the right, inscriptions in the earliest form written Chinese. These were incised upon a tortoise shell or ox scapulae and used for divination. Held over a fire, the cracks that emerged determined the message from the gods.

The Zhou Dynasty

The Shang Dynasty was followed by the Zhou Dynasty (1100-221 BCE), also centered along the Yellow River. In this period, many small regional states gave allegiance to the powerful state of Zhou in a sort of feudal system.

There was a great growth in knowledge, and many philosophies developed. This was the era of the great Chinese educator, Kongzi (Confucius), his disciple Mencius or Mengzi, and of the third great classical Confucian thinker, Xunzi. Towards the end of this era, as the various states fought against each other to replace the Zhou, cast iron became important for weapons and tools.

The Qin Dynasty

Following the collapse of the Zhou Dynasty there arose a short, repressive, but very influential dynasty called the Qin (221-207 BCE). It was named after the state that won the struggles at the end of the Zhou.

Qin was ruled by Qinshi Huangdi. He set up a centralized bureaucracy headed by himself—an all-powerful emperor who had absolute authority over all of his subjects. He also standardized the written language as well as weights and measures. Unlike the Zhou, where the rulers of the various states had their own armies, Qinshi Huangdi had the entire military under his personal control. He forced his subjects to begin the Great Wall and built a massive tomb surrounded by armies of thousands and thousands of life-size warriors and horses made of a clay called terra-cotta. His style of government influenced succeeding dynasties in China and emerging kingdoms all over East Asia.

The Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian, writing a century after the First Emperor’s death, wrote that it took 700,000 men 39 years to construct the emperor’s mausoleum. Most of the workmen who built the tomb were killed to keep its location secret.

While Sima Qian never mentioned the terracotta army, the statues were discovered by a group of farmers digging wells on March 29, 1974.

The soldiers were created with a series of mix-and-match clay molds and then further individualized by the artists’ hand. There are around 6,000 Terracotta Warriors made to protect the Emperor in the afterlife from evil spirits. Also among the army are chariots and 40,000 real bronze weapons.

The main tomb containing the emperor has yet to be opened and there is evidence suggesting that it remains relatively intact. Sima Qian’s description of the tomb includes replicas of palaces and scenic towers, “rare utensils and wonderful objects”, 100 rivers made with mercury, representations of “the heavenly bodies”, and crossbows rigged to shoot anyone who tried to break in.

Sanxingdui Culture / Kingdom of Shu

Sanxingdui is a previously unknown bronze age culture whose artifacts were discovered in 1987 in what is now Sichuan. This culture is now being identified with the ancient kingdom of Shu, c. 316 BCE. These finds challenge the narrative of Chinese civilization spreading only from the Yellow River/North China plain and make the case, along with other recent finds, for a view of Chinese culture as having multiple early centers of innovation.

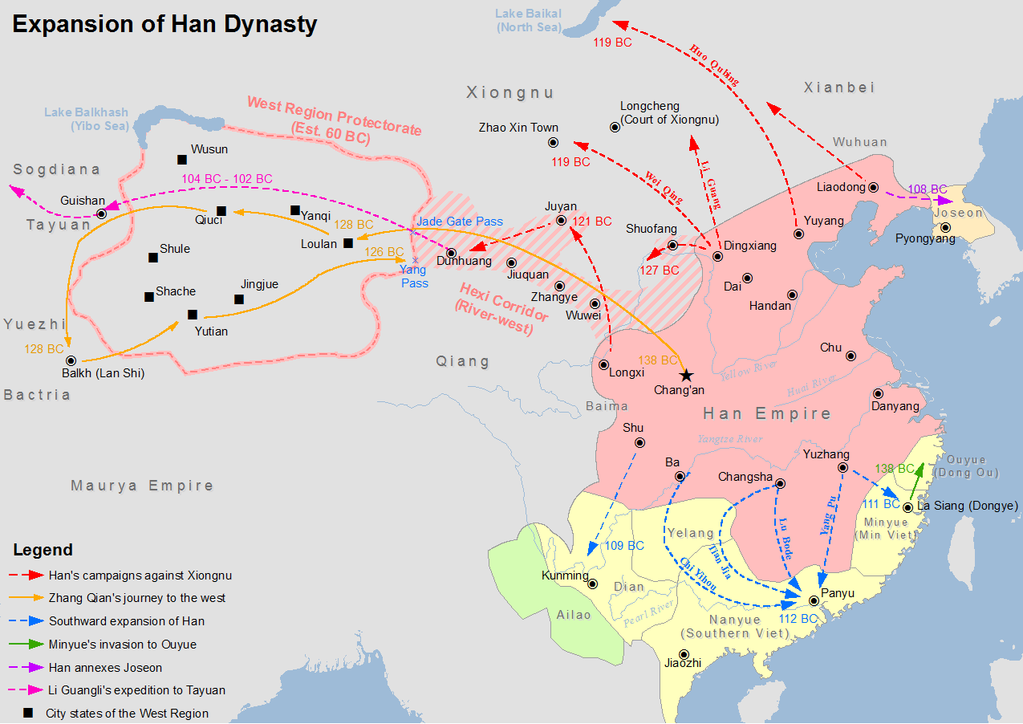

The Han Dynasty

The Qin dynasty fell after the death of the first emperor. It was followed by the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), which lasted about four hundred years. We see also, here with this map, how great an area the dynasty comes to control. It penetrates much farther south and also west.

The Han Dynasty was a rich and powerful state roughly contemporaneous with the Roman empire. Under the Han, a modified imperial system made life more bearable for the common people, intellectuals were appreciated, and trade, art, and literature flourished. Confucianism was also codified and systematized into the official ideology whose influence dominated everything from the collecting of folksongs and poetry to the institution of the system of imperial examinations that would last, in some form, for the next two millennia. The Han nationality, China’s largest ethnic group, is named for this great dynasty.

The cultural innovations in the early Chinese kingdoms influenced the growth of city culture and organized states on the Korean peninsula and Japan. Writing, philosophies such as Confucianism, government structure, and technological innovations were introduced in a variety of ways to areas that would eventually become the Three Kingdoms in Korea (57 BCE-668 CE) and the cultures of the Tomb Period (300-552 CE) in Japan.

Three Kingdoms of Korea and the Tomb Period of Japan

Here is a map of the three kingdoms of Korea—Goguryeo, Baekje (Paekje) and Silla—at the end of the 5th century CE.

An outstanding feature of both these periods in both Korea and Japan was the appearance of large tomb mounds, or tumuli, such as the green, grassy mounds found near Gyeongju on the Korean peninsula southeast of Seoul.

Both mounded and key-hole shaped tombs are associated with ancient capitals in Japan. This is Daisen Kofun, the immense keyhole-shaped burial site of the Emperor Nintoku, a legendary 5th century ruler, that is the largest of the thousands of kofun still in Japan.

The Kofun, or tombs, give their name to the Kofun Period in Japanese history, from the 3rd to the 6th century CE.

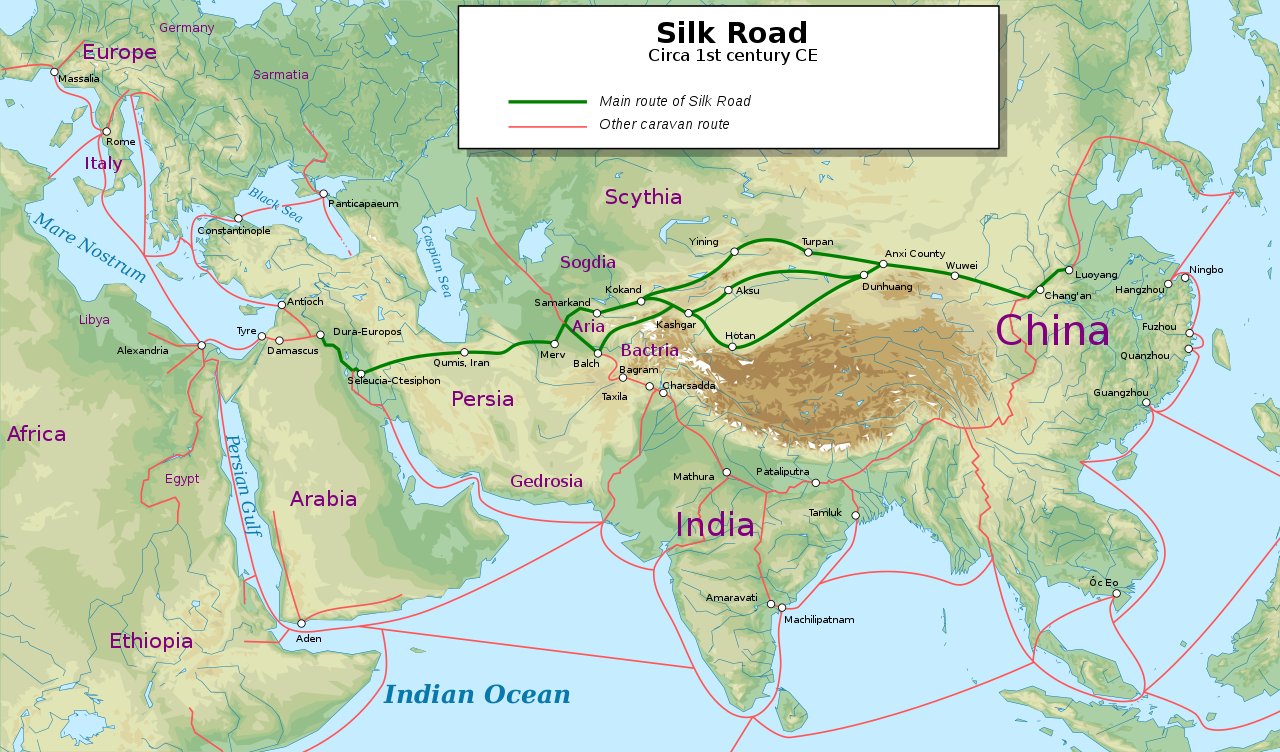

3. THE SILK ROAD ERA (200-1000 CE)

The Silk Road was a valuable overland trade route between the ends of Asia. It was most active from at least the 1st century CE until the late 10th century. Named for its most famous trade commodity—Chinese silk—the route was probably based on trails that date back far into prehistory.

Indeed, recent archaeological digs in northwest China have uncovered 4,000 year-old graves containing blonde mummies buried in the garments of cloth that indicate links to Celtic Europe.

Key Features of the Silk Road Era:

Valuable overland trade route between ends of Asia: most active from at least 1st Century CE until the 10th

Transgressed imposing geographical barriers: harsh deserts and tall mountains

Connected East Asia with Central Asia, India, Middle East, and Mediterranean cultures

Before the development of reliable ocean networks the Silk Road route served to link Mediterranean Africa and Europe, the Middle East, and India with Central Asia and East Asia in an exchange route on which goods, technology, and ideas passed.

The overland route was long and dangerous. Camel caravans had to navigate baking deserts that froze at night, cross treacherous mountain ranges, and deal with bandits and hostile natives.

As we see on this map, Caravans moved between a chain of oases that stretched from Central Asia into northwest China, to the capital of the great Tang dynasty ( 618-906 CE) at Chang’an (modern Xi’an), close to the grave of the first emperor, Qinshi Huangdi, with its famous terracotta army noted above. Routes connected further east to the Korean peninsula, and across the Yellow Sea to Japan.

Much of the area between China and Western Asia is taken up by the Taklimakan desert, one of the most hostile environments on our planet. There is very little vegetation, and almost no rainfall; sandstorms are very common, and have claimed the lives of countless people. caravans throughout history have skirted its edges, from one isolated oasis to the next.

In crossing this vast Central Asian region several different branches developed, passing through different oasis settlements. The routes all started from the capital in Chang’an (modern Xi’an), headed up the Gansu corridor, and reached Dunhuang on the edge of the Taklimakan.

The northern route then passed through Yumen Guan (Jade Gate Pass) and crossed the neck of the Gobi desert to Hami (Kumul), before following the Tianshan mountains round the northern fringes of the Taklimakan. It passed through the major oases of Turfan and Kuqa before arriving at Kashgar, at the foot of the Pamirs. The southern route branched off at Dunhuang, passing through the Yang Guan and skirting the southern edges of the desert, via Miran, Hetian (Khotan) and Shache (Yarkand), finally turning north again to meet the other route at Kashgar.

Numerous other routes were also used to a lesser extent.

A further route split from the northern route after Kuqa and headed across the Tianshan range to eventually reach the shores of the Caspian Sea, via Tashkent.

Although the history of the Silk Road is very much a history of interaction between nomadic and sedentary cultures, much of the economic and cultural development people normally think of in connection with the Silk Road has been in urban settings.

A source of silk, Chang’an, now Xi’an, capital of Tang China, was a major Silk Road destination during the 7th-9th centuries, making this city perhaps the most sophisticated, diverse and wealthy of its time.

There was a great deal of ethnic and cultural diversity on the Road.

Across the entire landmass of the Silk Road many kingdoms and empires developed over several centuries. To the East were the powerful Chinese dynasties – like the Han and Tang. In the central part spread over Iran, Iraq, Mongolia and Transoxiania (present day Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakastan, Kyrghystan) were the Sakas, Sogdians, Sassanians, Mongols, and Timurids. In the western part of the Silk Road there were the Macedonians, Byzantines and the Ottomans. In the southern part of the Silk Road which included Northern India, Pakistan and Afghanistan there were the Kushans, Guptas and Mughals.

The cultures at the opposite ends of the roads had little idea of each other. The Romans’ name for China was “Seres,” which means silk in Latin. As the route traversed many cultural areas, the merchants developed a lingua franca, a sort of trade language that was called Sogdian-from the ancient kingdom of Sogdia, which was somewhere between Afghanistan and Iran.

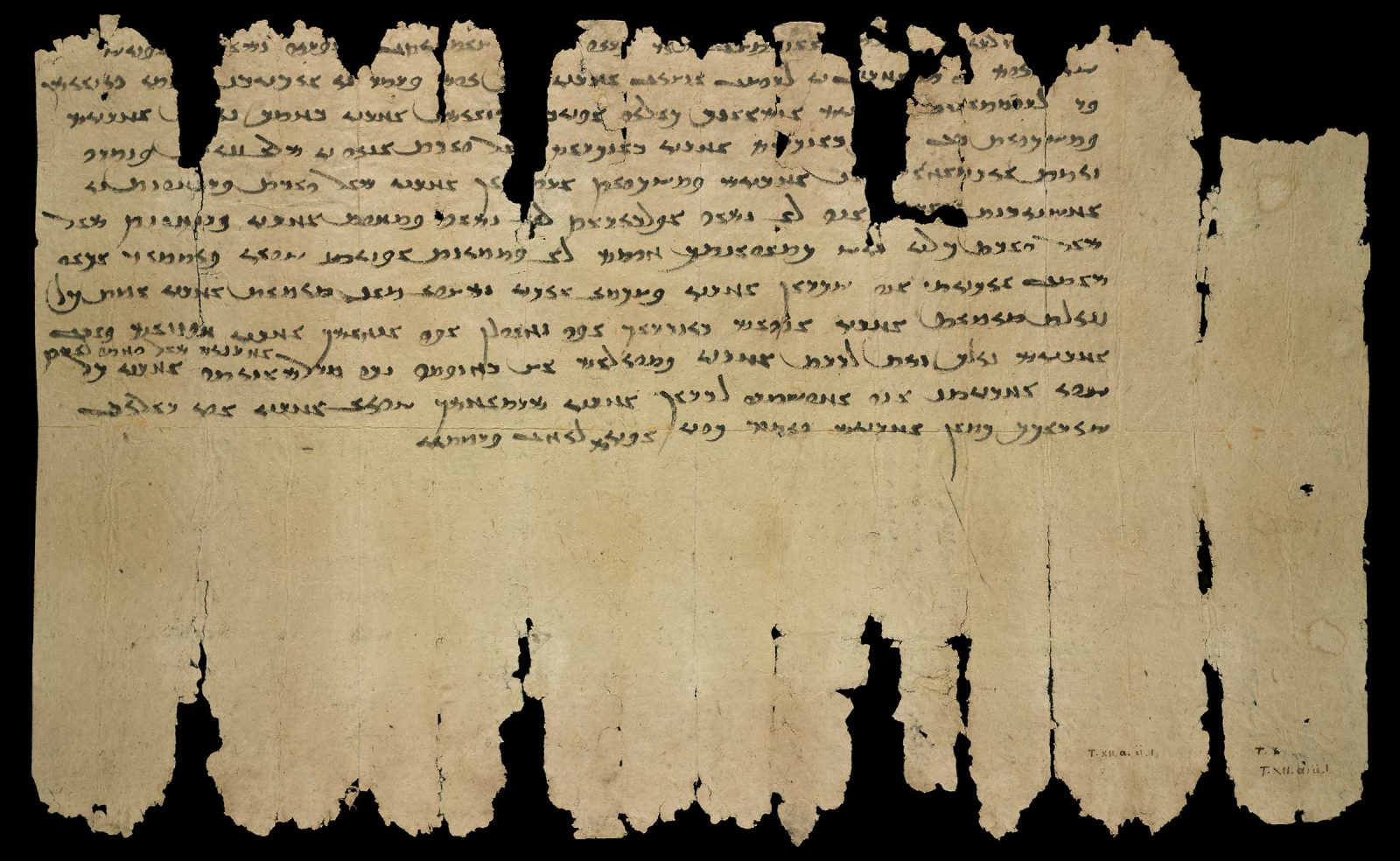

The illustration below is the fragment of a 4th century CE letter written by an abandoned Sogdian wife, found in a mislaid postal bag near Dunhuang in Gansu province, in the northwest of China.

Silk Road in Korea and Japan

The Korean peninsula served as land bridge to Nara and Heian (Kyoto), in Japan, making Japan’s ancient capital of Nara, in many respects, the de facto Eastern terminus of the Silk Road.

A great treasure horde of ancient art objects and handicrafts, many originating from countries along the Silk Road is housed in the Horyuji Temple complex near Nara. The Horyuji temple is one of four structures that has survived from the Asuka era (552-710 CE) for over 13 centuries.

Silk Road and Buddhism

Among the many other things that moved along the Silk Road-sometimes West, sometimes East, one of the most important was Buddhism. Buddhism was probably the biggest outside influence on worldview in East Asia until modern times. It spread from India into East Asia along overland routes in both north and south China. Records indicate that a few Buddhist monks traveled the road to Korea from as far West as Afghanistan.

The connections between Buddhism and the Silk Road are quite explicit. The earliest donors and some of the most important patrons of the Buddha and his followers were caravan merchants and wealthy bankers. Buddhist literature contains many epithets, stories, examples, and rules related to long-distance trade. To the right is a statue of Xuanzang, a 5th century Chinese monk, scholar and translator who made one of the most famous journeys on the Silk Road. His 17-year overland journey to India and back provided the inspiration for the famous Ming novel Journey to the West, which continues to be adapted and disseminated throughout East Asia and the world in many forms.

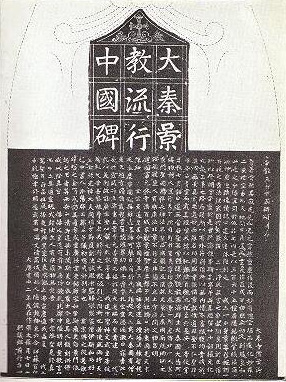

Religion and the Silk Road

Although Buddhism was the major religion in the areas along the Silk Road before the rise of Islam (which now dominates the areas) in the 8th century CE, there was a great deal of religious diversity that blossomed with the mix of people and cultures that traded along the route.

Other major religions of the period included Manicheanism and Nestorianism, the latter an ancient Christian sect represented by a Tang Dynasty tablet rubbing, as well as Zoroastrianism and Islam.

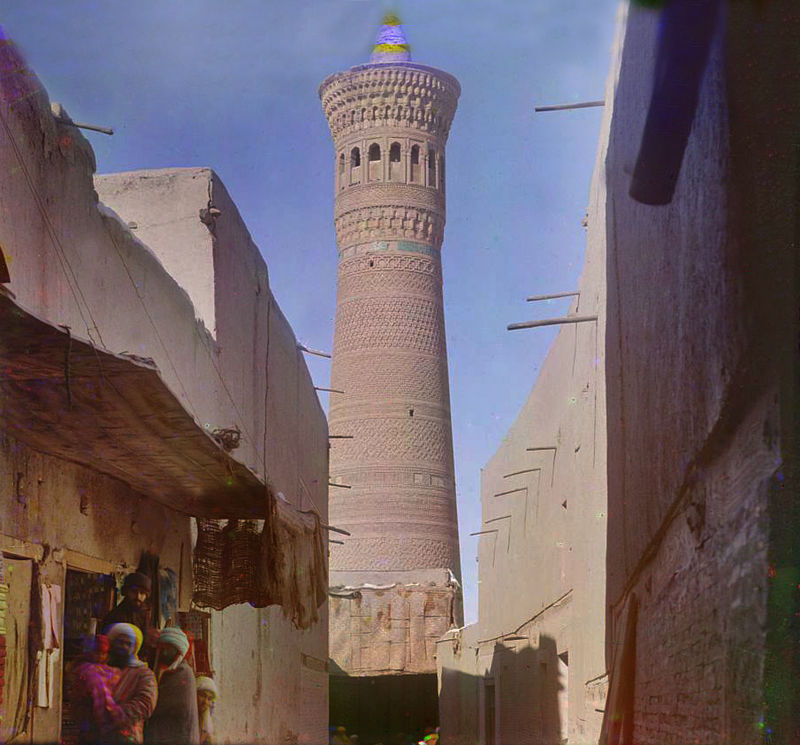

The image below is of the Kalyan minaret in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. The minaret, a feature of Muslim worship, was designed by Bako and built by the Qarakhanid ruler Mohammad Arslan Khan in 1127 CE.

Art of the Silk Road

Two thousand years before today’s “global economy,” an exchange network linked the continent of Asia with Europe via the Silk Route. The Silk Road fostered peaceful interaction, both cultural and commercial. Merchants, ambassadors, and pilgrims transported crafted goods and raw materials acquired from distant realms: spices, precious metals, musical instruments, rare medicinal herbs, objects used in worship and ritual, metal work, paintings, textiles and porcelain. Along with the much-sought after silk, jade, exotic gems, rare metals, medicines, furs, antlers, perfumes, paper and other luxury goods, as well as architectural and artistic patterns, technology, and ideas accompanied the caravans on their journeys.

Cultural Influences Still Felt Today

Other cultural items, such as storytelling that combined speaking and singing, certain dance moves, yogic practices, styles of drama spread from India into East Asia. Musical instruments from Central Asia also had far-reaching influences on the musical traditions of all the cultures in East Asia. Some of the performance genres influenced by Silk Road trade exist today in East Asia. China’s present “One Belt, One Road” development initiatives in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, follow much of the ancient Silk Road routes.

4. THE MONGOL PERIOD (1100-1400 CE)

The Republic of Mongolia is located just north of the area in China known as the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region. These areas, one a republic, and the other an administrative unit in China, are the present home of most of the Mongol people. This people ruled much of the world in the period from about 1100 to 1400 CE, creating the largest contiguous land empire in history. The military prowess and organization of the Mongols made them the nemesis of peoples stretching from Japan to the borders of North Africa and eastern Europe.

Under the first great Mongol ruler, Genghis Khan, the Mongol Horde formed from dozens of smaller nomadic tribes living all over the northern steppe lands. The effect of the Mongol invasions was devastating for East Asia. China and the Korean peninsula were both subjugated to Mongol rule. Though Japan was never successfully invaded, the military buildup to fend off Mongol attacks complicated the struggles among the island warlords. Even after the Mongols retreated to the grasslands, East Asia was still affected by their fearful legacy, evidenced in China by the rebuilding of the Great Wall during the Ming dynasty.

Genghis Khan, the greatest conqueror in world history, came from a place on the vast steppe lands of North Asia in what is now Mongolia. His father was a minor leader who was murdered by another tribe when Temujin (Genghis Khan’s childhood name) was still very young. He and his mother were soon kicked out of their band and had to fend for themselves in the wilds.

Overcoming this difficult start, Temujin skillfully gained stature and followers by forging alliances with various steppe rulers and staging several raids against rival tribes. As time passed, he gained power over and organized great numbers of the steppe tribes into a powerful fighting force, then set off to conquer the world.

When encountering the great walled cities of Central Asia and the Middle East, Mongol strategy was straightforward: surrender or face total annihilation.

When the Mongols conquered the Silk Road city of Bukhara after a lengthy siege, Genghis Khan sat in the great mosque and declared his victory a “punishment from God.”

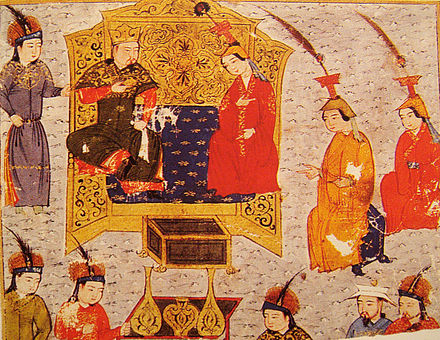

The Mongols spent many years attempting to invade China. Northern China fell in 1127 CE, but it took until 1279 for the entire country to come under the control of Kublai Khan, who declared himself emperor. To administer this vast and complex realm, Kublai imported many people from outside China to run the place. These people included many Muslim administrators from Central Asia and even a few Europeans, such as the Italian merchant Marco Polo, who worked as an official in the salt trade in Yangzhou.

|

|

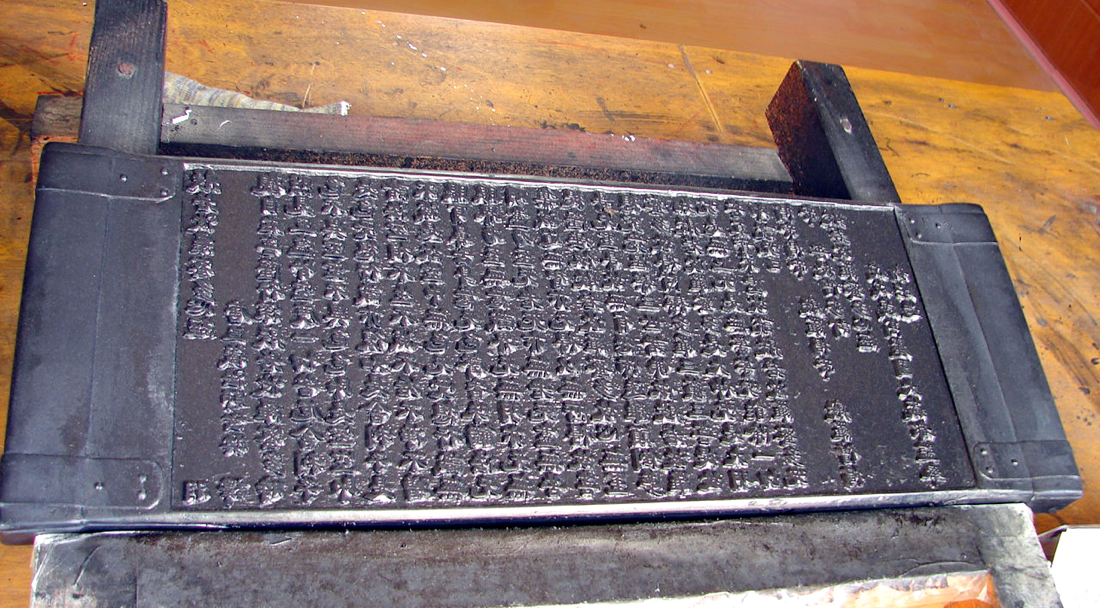

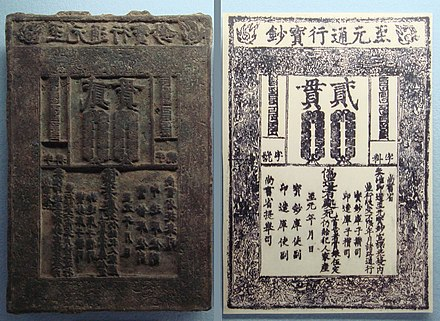

The Mongols also invaded the Korean penisula in six major campaigns, eventually reducing it to a vassal state for a period of 80 years. One innovation developed in the Koryo kingdom under the Mongol threat was moveable metal printing type—invented probably 50 or 60 years before it started in Europe. Both the Koreans and the Chinese were involved in the invention of movable type, but during the Mongol invasion wooden printing blocks used to print Buddhist scriptures were burned. Thus, cast bronze type was created to print the Buddhist scriptures. Though it is difficult to follow the path of such influences, this idea found its way to Europe

In general trade between East and West increased under the Mongols, due to the opening of safe new trade routes. It was also a time of great technological transfer and cultural contact. Among the technologies transferred from East to West were papermaking, the compass, and gunpowder. The irony is that in later eras Europeans enhanced some of these innovations and later circled the globe by sea in search of wealth in East Asia and other areas.

The Mongols tried to invade Japan by sea. These attempts at sea warfare failed. Mongols were masters of warfare on horseback but had to rely on impressed Korean or Chinese ships and sailors in their ventures at sea. During both attempts to invade Japan, the Mongol fleets of Kublai Khan were sunk by winds and storms. These protective winds were called the kamikaze, or “wind of the gods.”

5. URBAN AND MERCHANTILE CULTURES (1000 CE-1912 CE)

Rise of Great Urban and Mercantile Cultures

The roots of the incredible economic growth demonstrated by the countries of East Asia in the post-WWII era (1945-2000) have roots that go back a thousand years, to just before the Mongol conquest. From the period ranging from about 1,000 years ago in Song dynasty China, urban, mercantile cultures grew to new levels of sophistication in the region. By the 1500s, Europeans had found sea routes to the centers of wealth and industry in India, Southeast Asia, and the countries of East Asia, coming in search of spices, textiles, silk, porcelain, tea, and copper.

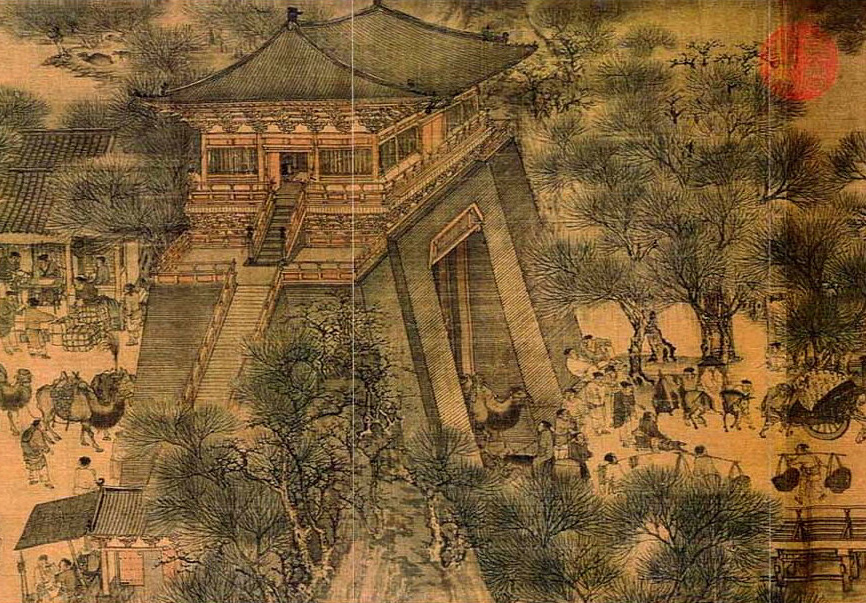

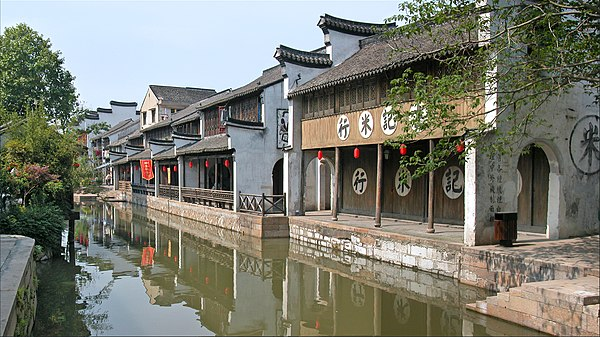

In China, cities grew up in the Yangzi River delta, far from the former Silk Road city Chang’an, capital of the fallen Tang Dynasty.

|

|

Here on the left we see a view of one of the many now ancient cities on China’s Grand Canal.

On the right is a map of the Yangzi River Delta area in China, an area that became the cultural and economic center of China during the Song Dynasty, marking a shift from the ancient dominance of the Northern Yellow River plain.

By the end of the 14th century, urban areas developed in new ways in Korea with the rise of Seoul.

In Japan, the rise of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1600 CE, laid the groundwork for 250 years of peace and economic developments, conditions that allowed the country to readily adapt to the new world order brought by Western Imperialism in the mid-19th century.

Urban and Mercantile Cultures: China

During the Northern Song dynasty, Jin tribes from the northeast invaded parts of northern China. As the invaders closed in, the emperor’s brother and many others of the lower caste fled south. These northern arrivals soon established the Southern Song dynasty at Hangzhou, lasting from 1127-1279 CE, until it finally fell to the Mongols. During this period, urban mercantile culture developed to new heights in the Yangzi River delta region.

Long regarded as exotic lands by northern Chinese, the southern areas in the Yangzi watershed were already rich from the development of local resources such as wood, salt, and lacquer, and the benefits of a milder, wetter climate suitable for producing multiple harvests of rice, and a huge variety of marketable fruits and vegetables. During the Southern Song, the lower Yangzi region soon became the center of Chinese commerce and industry, retaining that distinction thereafter. Today, the largest city in China is Shanghai, which arose in this area after the 1840s. New economic strategies during this period included the development of an extensive transport business linking north and south China comprised of an advanced inland canal network. The effect of this development was something like the rise of the railroad system in the United State in the latter 19th century. Social services were also instituted, including health care and benefits for widows and eligible poor.

Technology advanced rapidly, including the invention of huge water-powered machines with wooden gears that aided in agriculture and manufacturing. Among the many items produced and marketed were silk, cotton, lacquer ware, porcelain, paper goods (including toilet paper), fashion goods (scented wooden combs, lip rouge, facial powder, fingernail dyes, etc.), incense and other items. The economy grew to staggering proportions for this time in history. In some years the Song minted as many as 800 million copper coins. The government had monopolies on salt, alcohol, tea, and incense.

Professional guilds of merchants and artisans developed to protect and control markets. These included a vast array of artists and craftsmen, including jewelers, cutlers, gluemakers, storytellers, and even crab and honey dealers. The state held a monopoly on: salt, alcohol, tea, and incense. Many of these abundant and various items were consumed by a growing urban middle-class, thousands of whom lived in neatly constructed wooden houses. Scholar-officials and merchant-class families often lived lavishly.

The homes of the elites featured carved stone doorways and elaborate gardens. The cities that flourished in this era, such as Hangzhou, Suzhou, and Yangzhou, are famous tourist sites today. The urban culture created during the Song survived the Mongol invasion, and grew even more sophisticated during the Ming and Qing dynasties that followed.

Despite the internal progress of the Chinese economy and culture, by the 1450s, the Ming dynasty had given up the voyages of discovery that had carried huge Chinese armadas to the coast of east Africa earlier in the century under the guidance of the eunuch Zheng He. Instead, the fleets were burned, and increased monies were spent on refurbishing the Great Wall. By the end of the 18th century, China was to find its lead in economy and technology challenged by cultures from another quarter of the world.

Urban and Merchantile Culture: Korea

In Korea, the collapse of the Mongols saw the rise of a new dynasty called Joseon (Choson), or Yi. Lasting from 1392-1910 it was one of the longest lasting dynasties in the History of East Asia. Seoul became the new capital and by 1399 the government had licensed a large marketplace, with monopolies on certain consumer goods granted to favored families in return for taxes. Merchant guilds and other markets gradually established. In 1403, a Korean king ordered that bronze metal type be used for printing all important documents, and printing helped to stimulate the economy.

In opposition to the Buddhist power structures previously dominant, the Joseon oversaw the entrenchment of Confucian cultural ideas and imported Chinese culture, adapting it to produce a Korean Confucian establishment. The Joseon also consolidated territorial control over the territory of what is currently North and South Korea.

During the Joseon, Korea classical culture, trade, and technology reached their apex and much of modern Korea’s language, cultural attitudes and norms are shaped by the legacy of this period.

An example of this phenomenon is hanbok. The term literally means “Korean Clothing” but the term Hanbok often refers specifically to the clothing styles of the Joseon Dynasty. This traditional dress is still worn in contemporary Korea for formal occasions and traditional festivals and celebrations.

During the 15th century, merchants guilds and markets diversified. During the reign of King Seonjo in the 16th century, the six largest taxpayers were called, “The Six Licensed Stores.” They sold silk, cotton, and other goods, combining manufacturing with selling. The privileges of these stores were revoked in the late 18th century in a “commercial equalization” act, and finally disappeared when Korea was colonized by Japan in 1910.

Remnants of several famous Seoul markets remain today at East Gate Market (at Dongdaemun) and South Gate market (at Namdaemun) located at the former city gates (now surrounded by skyscrapers). They still sell all sorts of goods, including foodstuffs, cloth goods, household goods, hardware, jewelry, wines, ginseng, and tobacco. Young couples preparing for marriage can buy every necessity for their new households in hundreds of small shops in these areas.

Urban and Mercantile Culture: Japan

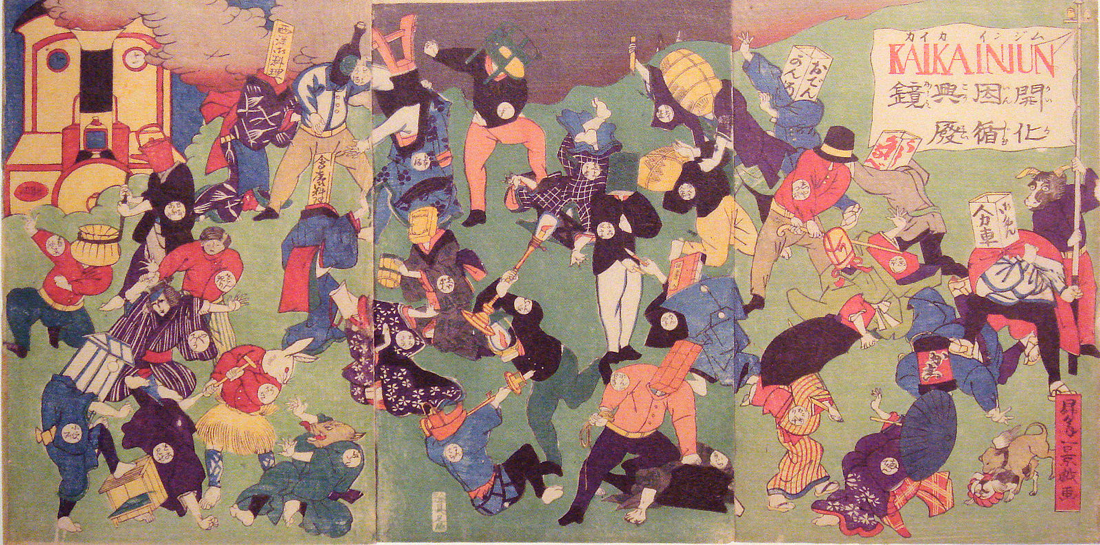

The urban, mercantile culture of Japan exploded after 1600 CE at the beginning of the Tokugawa period. This period, unique in world history lasted for 250 peaceful years in which Japan was closed to the outside world and internal markets developed and flourished, producing a rising merchant class and burgeoning urban scene.

Edo, today’s Tokyo, became the greatest city in Japan, and was a seat not only of commerce and industry, but hosted an unworldly pleasure district (Ukiyo-e or “Floating World”) in which a wealth of performing and entertainment arts and services were available for the growing middle-class of merchants and producers. Osaka, father to the south, was also a city noted for commerce and pleasure, and roads were built linking the two cities.

Other roads were built to link the capital with other parts of the realm. As local lords and their massive retinues were ordered to make pilgrimages every three years to Edo, commerce was stimulated as lodgings, restaurants, and suppliers grew up along the routes of travel.

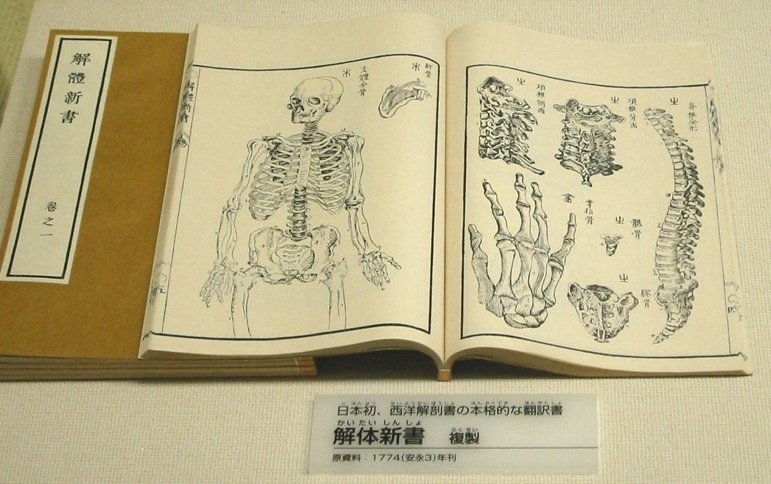

Though all but closed to outside influences, the increasing wealth of European knowledge on science and medicine trickled into Japan from Dutch traders, the only Westerners allowed in Japan after the early 1600s, when the Catholic Portuguese were expelled. By the mid-19th century, the Japanese economy and government had developed to such an extent that when Commodore Perry ordered Japan to open to trade, the county quickly introduced the best the West had to offer and was soon on its way to becoming a modern world power.

|

|

6. IMPERIALISM IN EAST ASIA (1600-1949 CE)

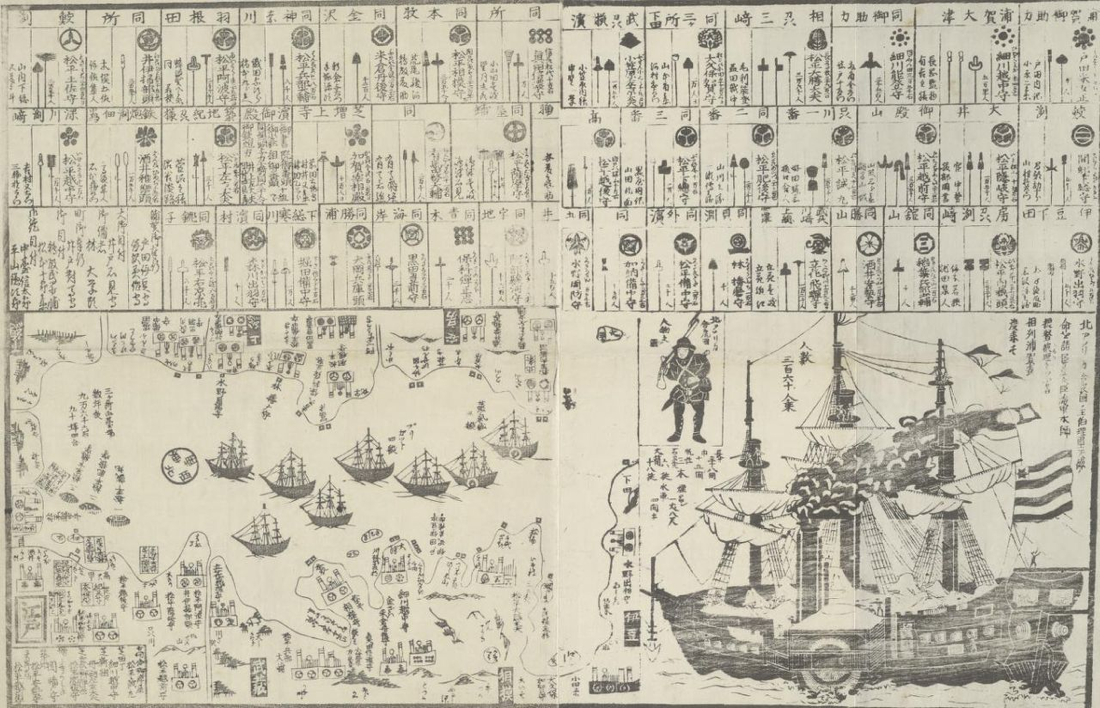

While the urban, mercantile cultures of East Asia were developing in the post-Mongol era, the peoples of Europe were positioning themselves for an era of discovery and economic growth based on imports from other areas of the world. As the peoples of East Asia began an inward turn, enjoying periods of relative peace and internal growth, Europeans were branching out on a global scale. The compass, improved rudders and sails, and gunpowder (all East Asian innovations), were elements that allowed European adventurers to follow their dreams of wealth, and eventually conquest. Items known from the old overland trade routes became more obtainable on the seas once the Indian Ocean was opened to free trade in the early 1500s after centuries of Arab domination. Textiles from India, spices from Indonesia, and porcelain, silk, and tea from China and Japan drew European traders from Portugal, Spain, Holland, England, and France into fierce rivalries that played out on several continents.

“Tall Ships” such as those used by Commodore Perry when “opening” Japan in 1853—and pictured above—were used by Western Imperialists visiting and trading in Asia until replaced by steamships in the 19th century.

There was always a search for swifter, cheaper routes to the East to the markets of East Asia and their incomparable wealth of consumer goods. Under contract with the king and queen of Spain, Christopher Columbus “discovered” the Americas in 1492 in an attempt to find a direct waterway to China and India. In 1803, US President Thomas Jefferson, bent on consolidating the US control over what is now the western half of the United States, funded the explorers Lewis and Clark on a “voyage of discovery” to chart lands recently purchased from France, and in search of a “Northwest Passage” to China. The mission was guided by a young Native American woman named Sacajawea, of the Shoshone tribe, who had been separated from her family and was familiar with much of the Upper Missouri River.

China

As the first Europeans sailed into East Asia, they were regarded with a mixture of curiosity and contempt. First involved in trade or missionary work (especially Catholic priests from Portugal and Spain), outposts gradually grew, and colonies were founded in India, Indonesia, Macao (on the coast of China), and the Philippines. For their part, the Chinese were perceived by the first European traders as arrogant because of their response to early Europeans: “You have nothing we want.”

Over time, Europeans made use of internal conflicts between native rulers (as in India) and the instabilities in the local economies. The latter factor applied to China during the late 18th and early 19th centuries when population growth, brought about by a good economy and New World crops like tobacco and sweet potato that could be grown on marginal lands. As rural populations swelled, uprising raged all over the country destablizing a Qing Dynasty already weakened by internal problems.

While the British had long sought Chinese tea, silks, and porcelain, the Chinese had wanted little but silver in return. The British finally hit on opium as an illicit, but profitable import into China, basing their operations in British India. In 1839-1842 the first of two Opium Wars was fought on the coast of China. When the Chinese government resisted, English gunboats smashed their forts with long-range cannon, and gained the territory of Hong Kong as well as concessions under Chinese law. With this defeat, the myth of Chinese power was broken and the nation sank into an era of denial and humiliation.

By the end of the 19th century, 8 European powers had armies on China’s soil and imperial gardens and tombs had been looted, many of the artifacts still residing in museums and private collections worldwide. In 1911, the old imperial system came to an end in an era of chaos and revolution that continued for decades. In the decades that followed, China suffered continued defeat and disintegration, war and great social foment, especially over the question of the way forward. It split in 1949 into the PRC and Taiwan, ROC. Hong Kong was not returned to Chinese sovereignty until 1997.

Japan

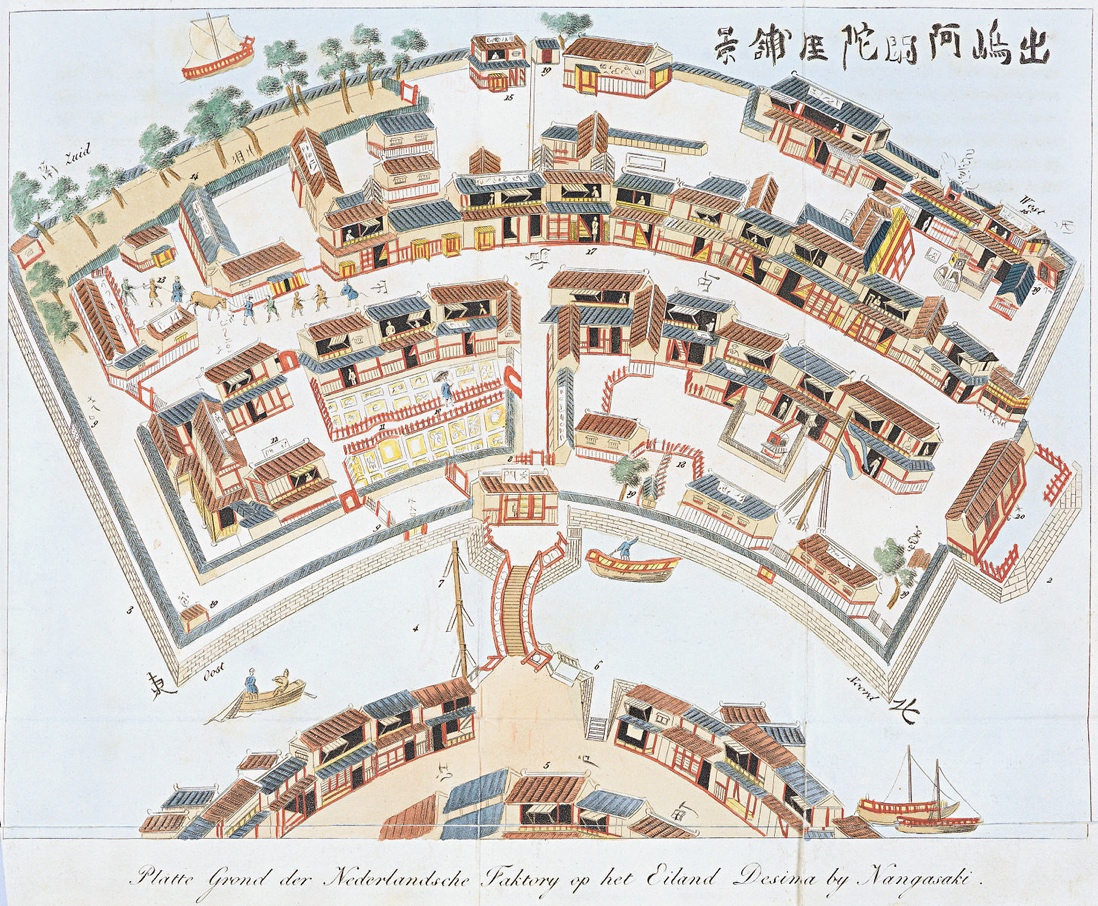

During the long Tokugawa period, Japan followed a policy of near isolation, having only select contact with the outside world. The picture above illustrates the Dutch trading post Decima or Dejima’, a small fan-shaped artificial island built in the bay of Nagasaki, Japan, in 1634 by local merchants, the single place of direct trade and exchange between Japan and the outside world during the Edo period. Dejima was built to constrain foreign traders as part of sakoku, the self-imposed isolationist policy. Originally built to house Portuguese traders, it was used by the Dutch as a trading post from 1641 until 1853. After the Portuguese were expelled in 1639. From 1641 on, only Chinese and Dutch ships were allowed to come to Japan, and Nagasaki harbor was the only harbor to which their entry was permitted.

Japan’s isolation finally melted in 1854: after seeing the outcome of the Opium War, it relented to American demands by U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry to open its doors. Within a few decades Japan had radically reinvented itself on Western models, importing experts in military, science, politics, and industry to help it revamp its society.

The Meiji Reformation of the 1860s led Japan onto the world stage and by the late 19th century the country began to assert itself by winning the Russo-Japanese war and by 1910 had taken Korea as a colony, dominating it until the end of World War II in 1945. During WWII, as an expansionist, imperialist power itself, Japan claimed many of the former European colonies all over the eastern half of Asia, and invaded large parts of China.

Korea

For its part, by the 18th century, Korea was also in decline having suffered a series of invasions from the Japanese in the late 16th century and the Manchus in the 18th. By the early 19th century it was known to Europeans as the “Hermit Kingdom,” as it did its best to withdraw from the world. Korea was then colonized by the Japanese from 1910-1945, then split into North and South after WWII

7. THE RISE OF EAST ASIA POST WWII (1949-PRESENT)

World War I (1914-1918) and World War II (1937-1945) refocused European interests away from Asia and Japan was stripped of its colonies after meeting defeat in 1945. Nationalist movements ignited in remaining colonies and newly liberated ones worldwide throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Korea was divided at the 38th parallel after the surrender of Japan, resulting in communist North Korea and democratic South Korea. The People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, while the island Taiwan remained under the rule of the Republic of China, founded in 1912 (though presently unrecognized as a nation by the United Nations). Thus, two cultural regions in East Asia remain divided today, remnants of the Cold War.

The big story has been the rise of local economies in East Asia since 1950, histories which are treated in Module 2.

Japan

As the nations recovered after WWII, the local economies in East Asia began to regain their economic vitality of centuries past. Japan, benefiting from military contracts during the Korean War (1950-1953), took off first with electronics and later automobiles. By the late 1980s, Japan was the world’s largest creditor nation and the US was the largest debtor. Japan’s technological innovation, high standards of production, and innovative popular culture have had a huge impact on world markets, with products ranging from the transistor radio, to automobile design, to Pokémon and electronic games.

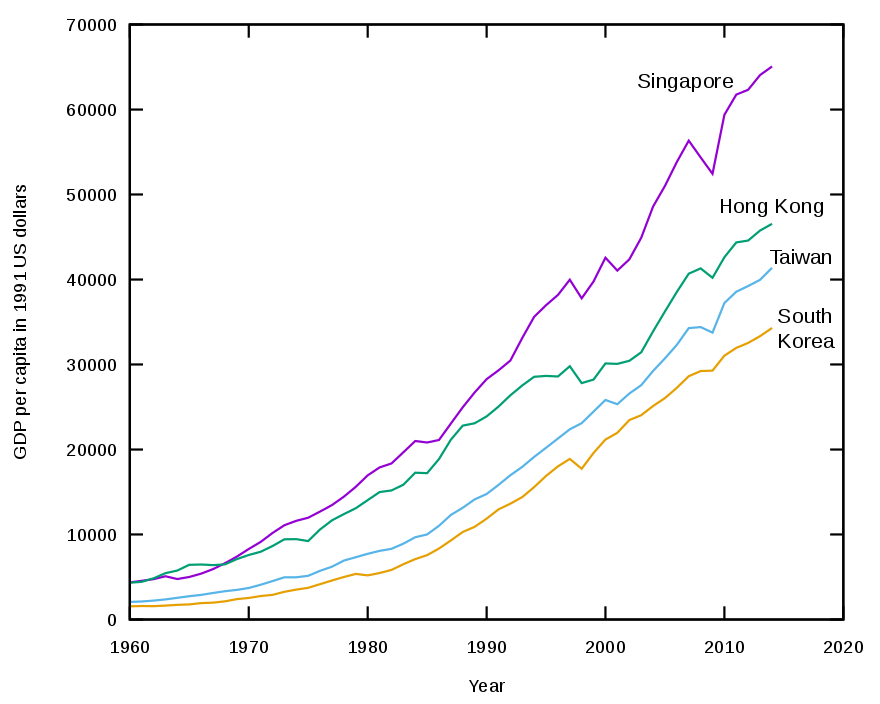

Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea’s economies followed suit in the 1970s and 1980s, earning the name “Four Asian Tigers.”

|

|

Korean Peninsula: South Korea

After the Korean War, the Korean Peninsula was divided along the 38th parallel. Recovering from nearly total devastation during this conflict, by the late 1980s South Korea had the fastest growing economy on earth. When the Asian economic bubble burst in 1997, it was the first nation to recover.

Since the 1990s with the coming of the “Korean Wave” South Korean popular culture, especially music, has roared into the East Asian and now global consciousness within a context of technological innovation and rising environmental awareness.

Korean Peninsula: North Korea

In the same period, North Korea has developed only militarily, having the third largest standing army on earth—as well as one of the world’s most isolated and enigmatic societies.

China

Since the later 1990s, the People’s Republic of China, which suffered decades of setbacks under irrational collectivist rule in the 1950s-1970s, has been finding its place in the world. Among the many milestones of the 30 years since its opening in 1979, the country entered the World Trade Organization in 2002, hosted the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, and has grown from “the bicycle kingdom” to the world’s second largest economy—a 21st century superpower. The 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was a much-celebrated milestone in July 2021.

Additional Media Playlist

This Playlist contains links to videos and articles that will enhance your understanding of the written text and offer new insights on East Asian Humanities.

- “The History of East Asia: Every Year” – an animated map of the political boundaries of East Asia over the past 4 thousand years

- A Tour of Chang’an – A video presenting an imaginary tour of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an), the largest city in the world during the late Silk Road Era

- Tokaido Road Manga Scrolls – An informative video about manga scrolls depicting Japan’s Tokaido Road, held at The Ohio State University Library

- Tripitaka Koreana – A video introducing the most well-preserved Buddhist scriptures in Korea (and East Asia), which is a testament to the influence of Buddhism in East Asia

- Taste-Testing Airag – A video about Mongolian kumis (also known as airag) today