History of the Sonnet

The Sonnet

by Shaun Russell

Few forms are more associated with Renaissance poetry than the sonnet. Thanks largely to the cultural awareness of William Shakespeare’s sonnets in particular (who among us doesn’t know the line “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”), “sonnet” is almost a household word. But what exactly is a sonnet, and when and why did sonnets become so popular?

What is a sonnet?

The simple answer is that a sonnet is a poetic form made of 14 lines, a standardized rhyme scheme, a consistent meter, and a “volta” (also known as a “turn”) that marks a tonal or thematic shift. Over the centuries, various poets have taken liberties by deliberately omitting or altering some of these four main components, but the vast majority of the sonnets you come across adhere closely to this form.

When were sonnets invented?

Technically, the sonnet is thought to have been invented in Italy by a thirteenth-century notary named Giacomo da Lentini, but the form was popularized by a fourteenth-century humanist scholar named Francesco Petrarca, usually anglicized as Petrarch.

Petrarch’s famous collection, Il Canzionere, features 366 poems (317 of which are sonnets), chiefly written in praise of a woman named Laura. The general theme of this sequence of poems is the unattainability of love—the “speaker” (essentially the poem’s narrator) seeks to love Laura, but is never quite able to obtain her love in return.

This style of poetry, written to express the unattainable love for another, is called Petrarchism. Some of the most common literary devices used in these poems are similes (e.g., “My love is like a flower”), metaphors (e.g., “My love is a flower”), conceits (e.g., “My love is pollen on the breeze”), and blazons—lengthy descriptions of the parts of the object of affection, usually from the top down (e.g., “My lover’s hair spills like a waterfall / Her eyes do glisten like two polished gems / Her voice is as the bird of heaven’s call” etc.). Notably, however, the object of affection is rarely given a voice.

Though it flourished in Italy for over two centuries, the sonnet only reached England in the 1530s. Scholars have long credited Sir Thomas Wyatt with bringing the sonnet to England via his many translations of Petrarch’s sonnets, along with his own compositions. Fellow courtiers in King Henry VIII’s court began to experiment with the sonnet form, most notably Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey, who is credited with the English sonnet form (see below). In 1557, long after Wyatt and Surrey had died, an important poetry collection titled Songes and Sonettes (but later referred to as Tottel’s Miscellany) was published, featuring many works by both poets, along with a large number of anonymous poems, including many sonnets.

Why did sonnets become popular?

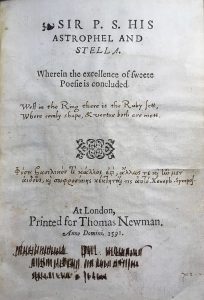

This question is open to speculation, but what we do know is that Tottel’s Miscellany proved to be very popular, going through ten editions between 1557 and 1586. Sir Philip Sidney, a lauded courtier in Elizabeth I’s court, wrote the first known Petrarchan sonnet sequence in English in the 1580s (titled Astrophil and Stella), and a great many poets opted to use the form from that point until the end of the Renaissance. The brevity of the form made sonnets easy to write in a short amount of time, while the universal theme of unrequited love never seemed to get old…though later sonneteers, such as John Donne, found that sonnets could be used to explore other themes.

Anatomy of a Sonnet

As mentioned above, there are four key components to a standard sonnet:

- Fourteen lines

- A standardized rhyme scheme

- A consistent meter

- A “volta” or “turn”

There are several variants that differ in their standardized rhyme scheme, the most important being what is commonly called the English sonnet (or less accurately, the Shakespearean sonnet), as contrasted with the Italian sonnet (also known as the Petrarchan sonnet).

In both English and Italian sonnets, the most common meter is iambic pentameter, which is meant to mirror the cadence of natural speech. An “iamb” is simply a term for two syllables together, where the stress is on the second syllable. For instance, words like “prepare,” “debate,” “embark,” and “suggest” all have a soft first syllable, and a stressed or emphasized second syllable. Pentameter refers to the number of iambs in a line: penta = five (in Greek). Therefore, a line of iambic pentameter (often abbreviated as IP) is usually ten syllables made up of five iambs. For instance, “I might suggest that you are now prepared” is a perfectly metrical line of IP:

I might | suggest | that you | are now | prepared

It is hard to read this line aloud without placing the stresses where they are. Of course, poetry is not meant to be rigid, so sonneteers will often make metrical substitutions to make the language flow more naturally. In other words, even though not every line is in perfect IP, the meter generally defaults to IP. If there are too many substitutions, the sense of meter is lost, which is disruptive to the ear.

A metrical substitution might look as follows:

I might | suggest | that you | are now | prepared

To high | light where | the me | ter adds | a stress

Since meter isn’t an exact science, with some speakers placing different emphasis on different words, it’s possible that you might read it differently…and that’s perfectly fine! Just remember that the point of meter is to adhere to a consistent (but not monotonous) rhythm.

As mentioned above, there are two dominant sonnet forms, based on their rhyme schemes: English and Italian. Because the Italian language has a far greater number of rhyming words, the Italian sonnet form has fewer distinct rhyming sounds in a rhyme scheme. A rhyme scheme simply refers to the number of end stresses in lines of poetry that rhyme with each other. Because of the rhyme scheme, Italian sonnets often have a two-part structure: an octave and a sestet. An octave is the first eight lines, and the sestet is the final six. In an Italian sonnet, the octave always has a rhyme scheme of ABBAABBA, where all the A’s are end words that rhyme with each other, and all the B’s are end words that rhyme with each other. Sestets in Italian sonnet form are less consistent, sometimes rhyming CDCDCD, sometimes CDECDE, or occasionally other variations.

An English sonnet is usually not broken down into octaves and sestets, but it is sometimes structured via its rhyme scheme into three quatrains and a couplet. A quatrain is a four-line unit, while a couplet is a two-line unit. While Italian sonnets were often written with a mere four rhyme sounds, English sonnets have a rhyme scheme of ABABCDCDEFEFGG, making for seven rhyme sounds in all.

Sonnet 12

William Shakespeare

(Example of an English Sonnet)

When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night;

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls, all silvered o’er with white; ←Quatrain 1 (ABAB)

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd,

And summer’s green all girded up in sheaves,

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard, ←Quatrain 2 (CDCD)

Then of thy beauty do I question make,

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake

And die as fast as they see others grow; ←Quatrain 3 (EFEF)

And nothing ‘gainst Time’s scythe can make defence

Save breed, to brave him when he takes thee hence. ←Couplet (GG)

Whoso List to Hunt

Sir Thomas Wyatt

(Example of an Italian Sonnet)

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind,

But as for me, hélas, I may no more.

The vain travail hath wearied me so sore,

I am of them that farthest cometh behind.

Yet may I by no means my wearied mind

Draw from the deer, but as she fleeth afore

Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore,

Sithens in a net I seek to hold the wind. ←Octave (ABBAABBA)

Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt,

As well as I may spend his time in vain.

And graven with diamonds in letters plain

There is written, her fair neck round about:

Noli me tangere, for Caesar’s I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame. ←Sestet (CDDCEE)

The final element of a sonnet, the volta (or “turn”), is more thematic than structural, and is therefore more subjective. Broadly speaking, sonnets tend to present one topic, theme, or argument, then turn to present another perspective on that topic, a counter-argument, or something that undermines the initial topic, theme, or argument completely. In many Italian sonnets, this turn is evident at the beginning of the sestet, often marked by words such as “but” or “yet,” while in many English sonnets, the turn can be found in the final couplet. Of all components of the sonnet, however, the location of this turn is the most variable.