John Milton: Devil’s Advocate

This week, you’ll be studying one of the most famous works of the English Renaissance, John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Paradise Lost takes as its point of departure Chapters 2 and 3 of the Book of Genesis, which recount how the serpent brought about the expulsion of humanity from paradise by convincing Eve to eat the forbidden fruit. From this biblical kernel, Milton builds an epic of stunning moral and psychological complexity. One of his greatest achievements is his depiction of Satan as a fallen angel wracked by self-doubt and resentment yet determined to rise again. Milton’s sympathetic portrayal of the devil prompted the Romantic poet William Blake (1757-1827) to declare that Milton was “of the Devil’s party, without knowing it.” When you read the selections for this week, you’ll see what Blake meant. Nor was Blake the only Romantic-era figure to consider Satan the true hero of Paradise Lost, or at least to find Milton’s charismatic rebel deeply moving. Sympathy for the devil likewise infuses the illustrations by Gustave Doré (1832-83) that accompany your readings below.

You’ll be studying episodes that focus on one important theme in Paradise Lost: persuasion. Persuasion causes Paradise to become lost, but the theme manifests itself well before the famous scene in the Garden of Eden. In episode after episode, Milton shows characters manipulating each other, sometimes through eloquence, sometimes through appeals to vanity and self-interest, sometimes through slick rhetorical tricks. The Council in Hell showcases dynamics that continue to be played out in professional, political, and business meetings today. Indeed, Paradise Lost might well be subtitled Influence.

For those of you thinking of performing a “set” of readings for your portfolio project, Paradise Lost provides some great choices for your Renaissance selection.

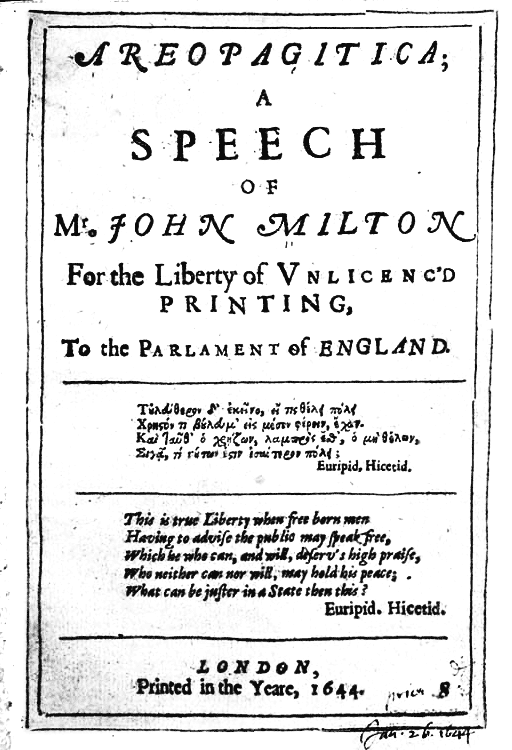

Milton was a prolific and outspoken pamphleteer who did not shy away from controversy. He defended the revolution that resulted in the execution of Charles I in 1649, championed freedom of the press, and argued for liberal divorce laws (for men). By the time he wrote Paradise Lost, glaucoma had rendered him completely blind. Renaissance scholar Richard Dutton writes, “All Milton’s poetry and prose…had to be composed within his head, a monumental act of memory and concentration; it was produced with the aid of amenuenses, often the women in his life, who did not have an easy time living with his genius.”

This video-lecture will give you some historical context for reading Paradise Lost:

Mastery Check:

- Milton was a disabled poet–what was his disability?

- What was the Gunpowder Plot and what was its significance?

- What were Milton’s views of freedom of the press, divorce, the execution of Charles I, and the Protectorate?

- William Blake considered Milton to be of whose party–and why?

And in this video lecture, Nick Hoffman will tell you more about this devil that Milton is supposed to have identified with. Where did he come from? Not, as you’ll see, from the Bible!

Mastery Check

- What is the Codex Gigas and how did it supposedly come to be?

- How is the devil represented in the Codex Gigas? What color are his claws and horns?

- In Genesis, who tempts Adam and Eve in the Garden of Evil?

- What Old English poem represents a Satan that resembles Milton’s?

- Give an example or two of how poets use Satan to reflect on the human condition.