Golden Age and Plague

The late fourteenth century was a “Golden Age” of English literature. One of its luminaries was Geoffrey Chaucer, our focus here.

Chaucer and his fellow authors wrote in a world shaped by one of the most catastrophic events of the late medieval period, the Black Death, which killed somewhere between a third and a half of the population of Western Europe. The plague reached England in 1348 and had enormous consequences for social, economic, and cultural life, as the video lecture below explains. For a full account of how the plague figured into the first recorded instance of biological warfare, read this article by Mark Wheelis.

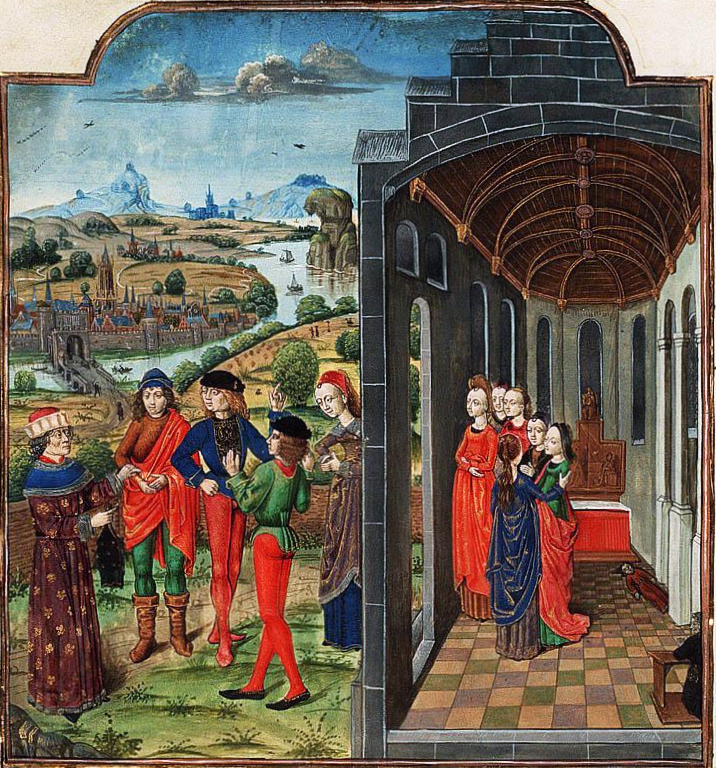

The plague had a powerful impact on the literary imagination. One of the most famous works it inspired is the Decameron, composed in 1353 by Chaucer’s Italian contemporary Giovanni Boccaccio. Set during the Black Death, the Decameron collects the stories purportedly told by ten young people (seven women, three men), who have fled plague-ridden Florence for what they hope is the safety of a country villa. To pass the time, and take their minds off death, these friends agree to tell stories. Each day, each of them will tell a story on a pre-determined topic—love stories that have ended happily (or unhappily), tricks men and women play on each other, etc. These stories are immensely entertaining. (They were my summer reading after I graduated from college, and I highly recommend them!) Chaucer was a great admirer of Boccaccio and adapted several of his works, including stories from the Decameron (the Clerk’s Tale, for example, which some of you may choose to read). In fact, the Decameron may have inspired The Canterbury Tales, which is also the story of the stories people tell.

But before we turn to The Canterbury Tales, indulge me as I share some thoughts about The Decameron and COVID-19. Boccaccio’s Decameron ends when, after ten days of storytelling, the friends agree to leave the villa and resume their former lives. That decision always struck me as odd because there was no apparent reason for their departure. The plague was still raging, and in returning to their old lives they risked the death they fled when they took refuge in the villa. It seemed as if Boccaccio just couldn’t bother bringing his work to a plausible conclusion. But as I write this in May, 2020, with a pandemic raging and states nonetheless “reopening” and protesters clamoring to be “liberated” and maskless multitudes mingling in bars like Standard Hall (Columbus Dispatch, May 16), it seems plausible that this group of friends might just have gotten sick of their quarantine and decided it’s time to get back to “normal,” whatever that means or brings. The medieval equivalent of “social-distancing fatigue”? Whether their decision was wise, Boccaccio doesn’t say. As I write this in Spring 2020, I don’t know the consequences (if any) of what strikes me as the premature relaxation of social distancing measures; as you read this in Autumn 2020, you will.

My reflections on how COVID-19 has changed my understanding of the end of Boccaccio’s Decameron illustrate how our understanding of the literature of the past is filtered through our lived experience in the present. That filter may distort, or it may bring us closer to the way a text was experienced by its original audience. It can be hard to tell.

[Now, of course, it is Autumn 2023. I thought of updating the paragraphs above and redoing the video lectures that reference COVID, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Not yet. So I’m retaining, for awhile, anyhow, my thoughts on our collective trauma as it was unfolding, a trauma that haunts us still. So much has happened in the last three years. What, if anything, has been learned?]

Food for Thought

Did your own experience of social distancing inspire any creative activities? Can you discern any ways in which our pandemic has produced a poetics that allows us to transform death and uncertainty into art?

Mastery Check:

- What is the Siege of Caffa’s claim to fame in the history of warfare?

- What opportunities and social changes resulted from the Black Death?

- How did Chaucer benefit from the Black Death?

- Was the Black Death a truly global pandemic or strictly a European event?

- What was the Decameron and how does it end?

The Black Death, also known as the Pestilence and the Plague, was the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, resulting in the deaths of up to 75–200 million people in Eurasia and North Africa, peaking in Europe from 1347 to 1351. Plague, the disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, was the cause; Y. pestis infection most commonly results in bubonic plague, but can cause septicaemic or pneumonic plagues.

The Black Death was the second plague pandemic recorded, after the Plague of Justinian (542–546). The plague created religious, social, and economic upheavals, with profound effects on the course of European history. (source: Wikipedia)

The Decameron, subtitled Prince Galehaut (Old Italian: Prencipe Galeotto) and sometimes nicknamed l'Umana commedia ("the Human comedy"), is a collection of novellas by the 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375). The book is structured as a frame story containing 100 tales told by a group of seven young women and three young men sheltering in a secluded villa just outside Florence to escape the Black Death, which was afflicting the city. Boccaccio probably conceived of The Decameron after the epidemic of 1348, and completed it by 1353. (source: Wikipedia)