Seizing the Moment

“You want to hear my philosophy? Life is short. Not original, I’ll grant you, but true. Why waste your time being all shy, worrying about some guy going to laugh at you. Seize the moment because tomorrow you might be dead.”

—Buffy Summers, Vampire Slayer (watch this segment on YouTube!)

Before there was. . .

Before there was. . .

There was…

carpe diem

Make Much of Time

Renaissance lovers were all about urging their “coy” (standoffish) beloveds to carpe diem, Latin for “seize the day.” After all, they remonstrate, you won’t be young forever, and you don’t want pass up a good thing (like having sex with me!). Of course, the trope didn’t end in the Renaissance. Back when I was in high school, Billy Joel was belting, “Come out Virginia, don’t let ’em wait / You Catholic girls start much too late” (“Only the Good Die Young,” 1977). I bet you can think of some current examples.

One of the most famous Renaissance iterations of “Carpe diem” is “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time” by Robert Herrick:

To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time

Robert Herrick (1591-1674)

Gather ye rose-buds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles today

Tomorrow will be dying.

The glorious lamp of heaven, the sun,

The higher he’s a-getting,

The sooner will his race be run,

And nearer he’s to setting.

That age is best which is the first,

When youth and blood are warmer;

But being spent, the worse, and worst

Times still succeed the former.

Then be not coy, but use your time,

And while ye may, go marry;

For having lost but once your prime,

You may forever tarry.

P.S. Your 60-year-old professor remonstrates: Don’t believe him! Pace Herrick, there is life after youth—it just gets better!

Mastery Check

- What four things does John Herrick exhort virgins to do?

- What does carpe diem mean?

To his Coy Mistress

Another masterpiece of carpe diem is Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress.” This poem is a stunning example of what is often known as “metaphysical” poetry. Metaphysical poetry is full of conceits (outrageous comparisons), paradoxes, and slick arguments that lead to dubious conclusions. These devices are abundantly displayed in Marvell’s mischievous poem. As you read it, paraphrase the Marvell’s argument—stripped of its fancy rhetoric, what does it amount to?

To his Coy Mistress

Andrew Marvell (1621-78)

Notes by Richard Dutton

Had we but world enough, and time,

This coyness, lady, were no crime.[1]

We would sit down, and think which way

To walk, and pass our long love’s day.

Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side

Should’st rubies find: I by the tide

Of Humber would complain. I would

Love you ten years before the Flood:

And you should, if you please, refuse

Till the conversion of the Jews[2]

My vegetable[3] love should grow

Vaster then empires, and more slow.

An hundred years should go to praise

Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze.

Two hundred to adore each breast.

But thirty thousand to the rest.

An age at least to every part,

And the last age should show your heart.

For, lady, you deserve this state;

Nor would I love at lower rate.

But at my back I always hear

Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near:[4]

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

Thy beauty shall no more be found;

Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound

My echoing song: then worms shall try

That long preserved virginity:

And your quaint[5] honor turn to dust,

And into ashes all my lust.

The grave’s a fine and private place,

But none I think do there embrace.

Now therefore, while the youthful hue

Sits on thy skin like morning dew,

And while thy willing soul transpires[6]

At every pore with instant fires,

Now let us sport us while we may;

And now, like amorous birds of prey,

Rather at once our time devour,

Than languish in his slow-chapped[7] power.

Let us roll all our strength, and all

Our sweetness, up into one ball,

And tear our pleasures with rough strife

Thorough[8] the iron gates of life.

Thus, though we cannot make our sun

Stand still,[9] yet we will make him run.

Mastery Check:

- What does Marvell hear at his back?

- What adjective does Marvell use to describe his coy mistress’s honor?

- If his coy mistress does not lose her virginity to him, what, does he say will happen to it?

- What does Marvell consider a “fine and private place,” but not for making out?

- What does Marvell propose that he and his mistress do with the sun?

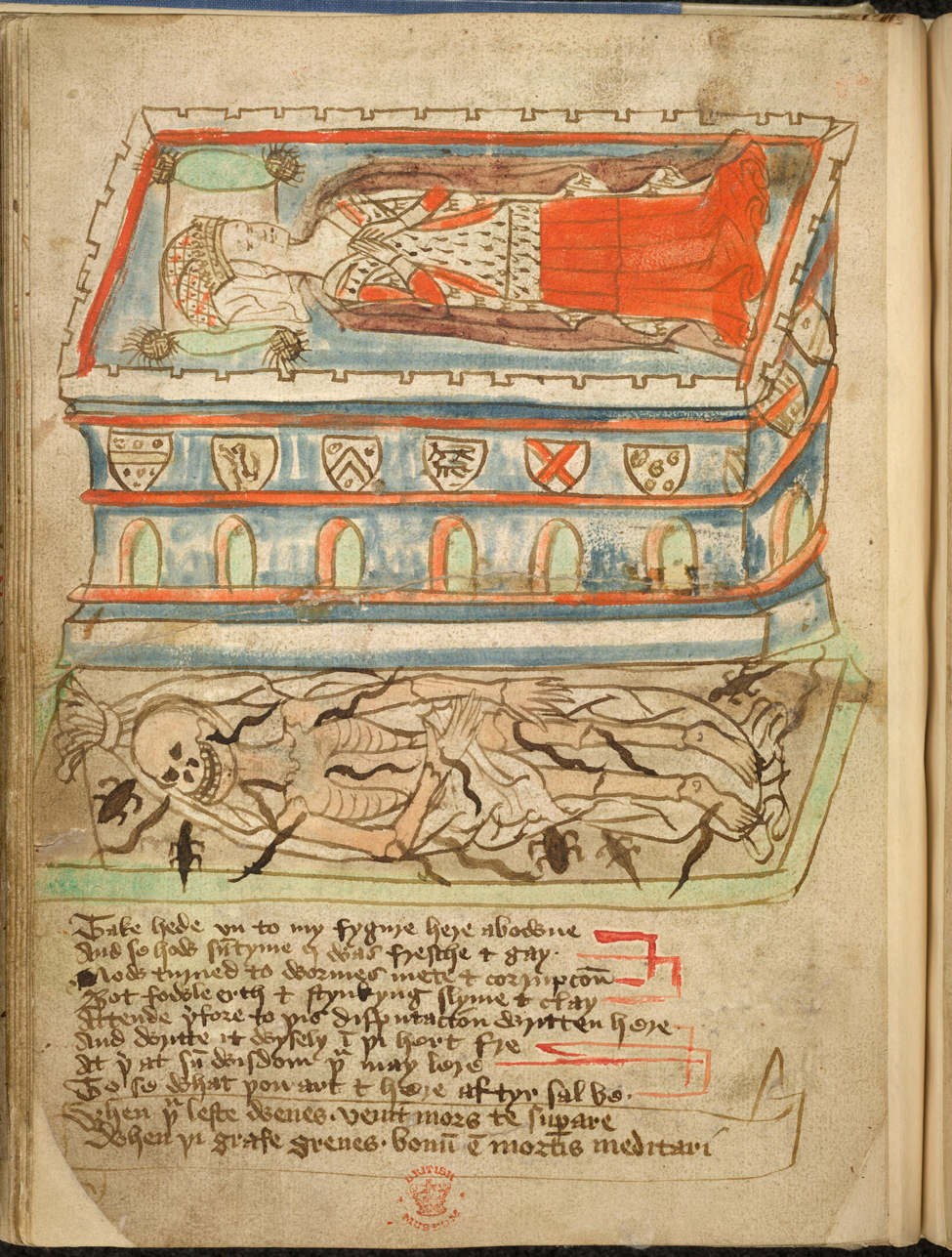

Cadaver Monuments

Cadaver monuments, such as John FitzAlan’s pictured above, are often “double-decker” tombs, the top representing the deceased as she or he was in life, the bottom representing the decaying corpse.

Below you will see an illustration of something rather like what Marvell may have had in mind for his coy mistress. On the top a beautiful woman reposes, while below worms are turning her “quaint honor” to dust. Note the cadaver’s right hand, positioned as if to try to keep one of the worms from her “queynte.”

Mastery Check

- What is a cadaver tomb, and what does it have to do with “To His Coy Mistress”?

- What would John Herrick, Andrew Marvell and Buffy Summers all agree on?

The Gender Politics of “Carpe diem”

It’ll probably come as no surprise to learn that Renaissance carpe diem poems were mostly written by men. The women they address don’t talk back. If they rolled their eyes, the poets don’t say. A generation after Marvell, Lady Mary Wortley Montague wrote what sounds for all the world like a response to Marvell’s “Coy Mistress.” Montague’s speaker, unlike Marvell’s, spells out the attributes she wants in a lover. As you read her poem, note what those attributes are. Does she want in a man what Marvell wants in a woman? Note also how Montagu’s “The Lover: A Ballad” refutes Marvell’s “Coy Mistress” formally, her directness contrasting with his paradoxes, conceits, and tortured argumentation. “Coy Mistress” is typical of Metaphysical poetry, “The Lover” typical of Augustan poetry.

The Lover: A Ballad

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762)

At length, by so much importunity press’d,

Take, C——, at once, the inside of my breast;

This stupid indiff’rence so often you blame,

Is not owing to nature, to fear, or to shame:

I am not as cold as a virgin in lead,

Nor is Sunday’s sermon so strong in my head:

I know but too well how time flies along,

That we live but few years, and yet fewer are young.

But I hate to be cheated, and never will buy

Long years of repentance for moments of joy,

Oh! was there a man (but where shall I find

Good sense and good nature so equally join’d?)

Would value his pleasure, contribute to mine;

Not meanly would boast, nor would lewdly design;

Not over severe, yet not stupidly vain,

For I would have the power, tho’ not give the pain.

No pedant, yet learned; no rake-helly gay,

Or laughing, because he has nothing to say;

To all my whole sex obliging and free,

Yet never be fond of any but me;

In public preserve the decorum that’s just,

And shew in his eyes he is true to his trust;

Then rarely approach, and respectfully bow,

But not fulsomely pert, nor yet foppishly low.

But when the long hours of public are past,

And we meet with champagne and a chicken at last,

May ev’ry fond pleasure that moment endear;

Be banish’d afar both discretion and fear!

Forgetting or scorning the airs of the crowd,

He may cease to be formal, and I to be proud.

Till lost in the joy, we confess that we live,

And he may be rude, and yet I may forgive.

And that my delight may be solidly fix’d,

Let the friend and the lover be handsomely mix’d;

In whose tender bosom my soul may confide,

Whose kindness can soothe me, whose counsel can guide.

From such a dear lover as here I describe,

No danger should fright me, no millions should bribe;

But till this astonishing creature I know,

As I long have liv’d chaste, I will keep myself so.

I never will share with the wanton coquette,

Or be caught by a vain affectation of wit.

The toasters and songsters may try all their art,

But never shall enter the pass of my heart.

I loath the lewd rake, the dress’d fopling despise:

Before such pursuers the nice virgin flies:

And as Ovid has sweetly in parable told,

We harden like trees, and like rivers grow cold.[10]

Mastery Check

- What is Montagu’s view of fleeting time?

- What specific arguments made by Marvel in “To His Coy Mistress” does Montagu refute in “Lover”?

- What does Montagu want in a lover?

- What does Montagu think of public displays of affection?

- How does Daphne escape Apollo?

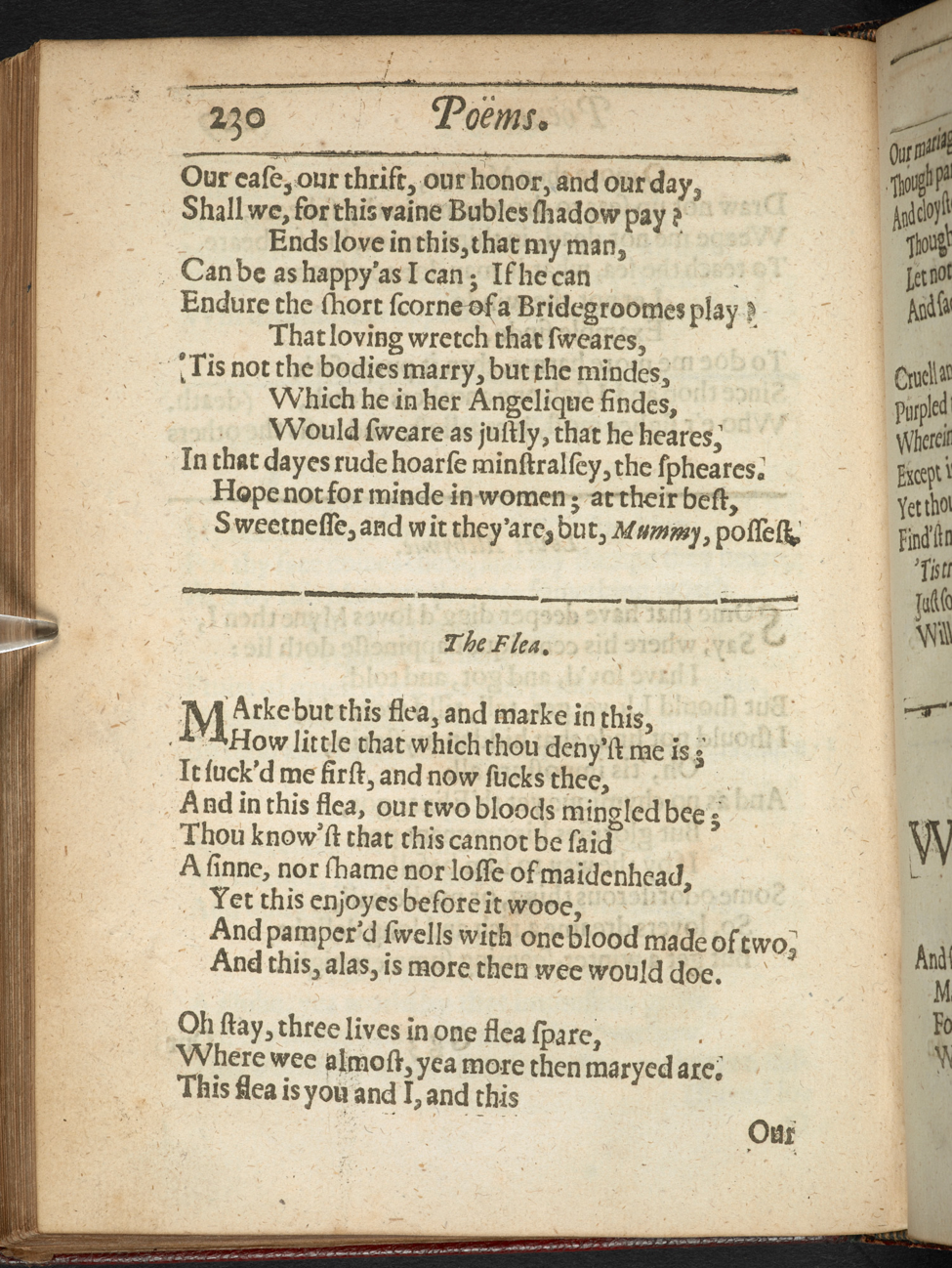

The Flea

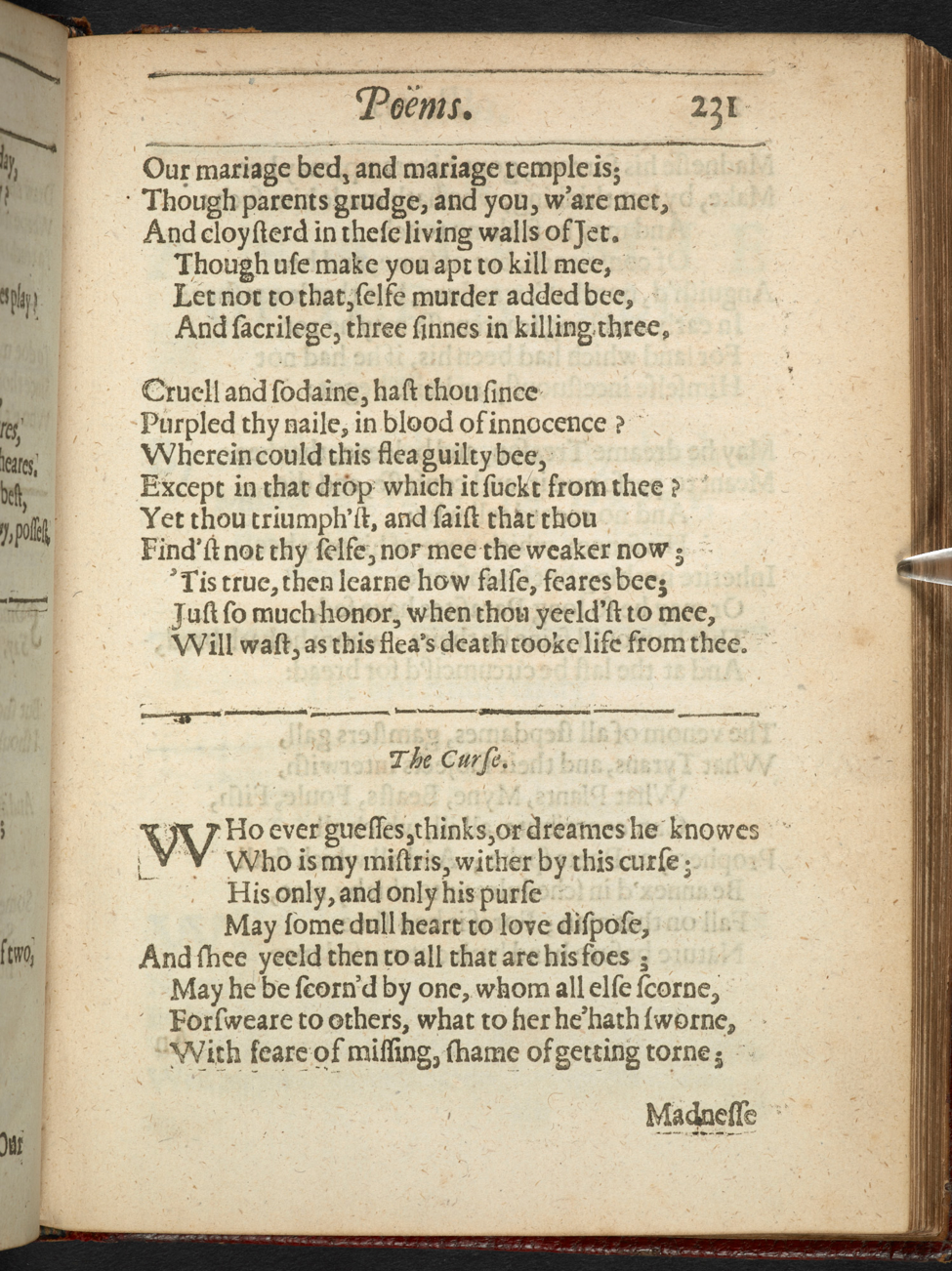

Let’s conclude this section on carpe diem poems with John Donne’s “The Flea.” In this poem, Donne develops a single brazen conceit, comparing being bitten by a flea to having sex. As I’ve already mentioned, poet seducers usually aren’t very specific about the objects of their affections. We don’t get much of a sense of their personality or appearance. They rarely speak. Donne’s “Flea” is different: after each stanza, the beloved does (or says) something, forcing the lover to change tacks. Be alive to what’s going on in the poem’s white space!

Part of the poem’s audacity hinges on the similarity in Renaissance handwriting and typeface between “f” and “s.” For that reason, I’ll give you the poem as it appeared in its first print edition:

Mastery Check:

- What two actions Donne’s mistress actions in the white space that separates the stanzas?

- Some of the raunchiness of Donne’s “The Flea” results from the similarity between which two letters?

- Donne likens sex to what?

- In what respect is the flea like the Trinity?

- To what Biblical event does Donne allude in his reference to “blood of innocents”?

- What does Donne’s mistress say?

- Can’t you just see the “coy mistress” rolling her eyes? ↵

- ten … Jews: this is, throughout history. Noah’s flood is one of the earliest events recorded in the Bible; popular tradition had it that the Jews would be converted to Christianity just before the Last Judgement. ↵

- vegetable love: The unconscious, physical powers of attraction, as distinct from spiritual love. ↵

- There’s always a “but,” isn’t there? This image is as outrageous as the argument it accompanies. Marvell’s claim: if his “coy mistress” won’t have sex with him, she won’t ever have sex, and then she will die, and the worms will do with her “quaint” what she wouldn’t let him do! This stanza puts me in mind of the so-called “cadaver tombs” popular in the late Middle Ages. For more on this phenomenon, see below.Enter your footnote content here. ↵

- quaint: A complex pun: the word has may meanings including elegant, fastidious, and old-fashioned; it is also a play on the medieval “queynte” or female genitals. ↵

- transpires: breathes out ↵

- slow-chapped: slow-jawed ↵

- thorough: through ↵

- Stand still: Zeus ordered the sun not to shine, so as to prolong his dalliance with Alcamena; see also Joshua 10.12-13. ↵

- The Classical Roman poet Ovid (10 BCE- 17/18CE) recounts this story in his Metamorphoses.: Apollo desires the river nymph Daphne, but she doesn’t desire him. Not being a god who takes “no” for an answer, Apollo chases after her. As he’s about to catch her, she begs her father, the river god, to save her. He turns her into a laurel tree. The frustrated god declares that if she can’t be his lover, she’ll at least be his tree. To signal his possession, he ordained that the laurel’s leaves should remain perpetually green. ↵

Carpe diem is a Latin aphorism, usually translated "seize the day." (source: Wikipedia)

Robert Herrick (baptised 24 August 1591–buried 15 October 1674)[1] was a 17th-century English lyric poet and cleric. He is best known for Hesperides, a book of poems. This includes the carpe diem poem "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time", with the first line "Gather ye rosebuds while ye may". (source: Wikipedia)

Andrew Marvell (/ˈmɑːrvəl, mɑːrˈvɛl/; 31 March 1621 – 16 August 1678) was an English metaphysical poet, satirist and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1659 and 1678. During the Commonwealth period he was a colleague and friend of John Milton. His poems range from the love-song "To His Coy Mistress", to evocations of an aristocratic country house and garden in "Upon Appleton House" and "The Garden", the political address "An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell's Return from Ireland", and the later personal and political satires "Flecknoe" and "The Character of Holland". (source: Wikipedia)

A cadaver monument is a type of church monument to deceased persons featuring a sculpted effigy of a skeleton or an emaciated, even decomposing, dead body. It was particularly characteristic of the later Middle Ages and was designed to remind the passer-by of the transience and vanity of mortal life and the eternity and desirability of the Christian after-life. The person so represented is not necessarily entombed or buried exactly under the monument, nor even in the same church. (source: Wikipedia)