9 Ignatius Sancho (1729-1780)

Introducing Ignatius Sancho

According to his contemporary biographer, Joseph Jekyll, Sancho was born circa 1729 aboard a slave ship crossing the Middle Passage. His mother died of disease, and his father committed suicide so that he would not have to endure slavery. Sancho was purchased by three sisters living in Greenwich, who, as he wrote in a 1766 letter, “judged ignorance the best and only security for obedience”; however, their neighbor, the Duke of Montagu, took a fancy to the boy and saw that he learned reading, writing, and music. He ran away from the sisters and joined the Montagu household, where he was a trusted valet. When the Duchess of Montagu died, she bequeathed him a year’s salary and an annuity of about thirty pounds.

Sancho had a wild spell during his youth. His biographer claims he spent his last shilling so that he could watch a performance of Shakespeare’s Richard III, starring David Garrick. (Remember the figurine of David Garrick as Richard III in Bundle 1, “Gallery of Readers”?)

Sancho loved the theater! Had he not suffered from a speech impediment, he would have pursued an acting career. Instead, he and his wife, Anne Osborne, opened a grocery store in London. Writing as he prepared to open shop in 1773, he enthused: “I verily think the happiest part of my life is to come–soap, starch, and blue [detergent], with raisins, figs, &c.–we shall cut a respectable figure–in our printed cards.” Here’s one of those printed cards:

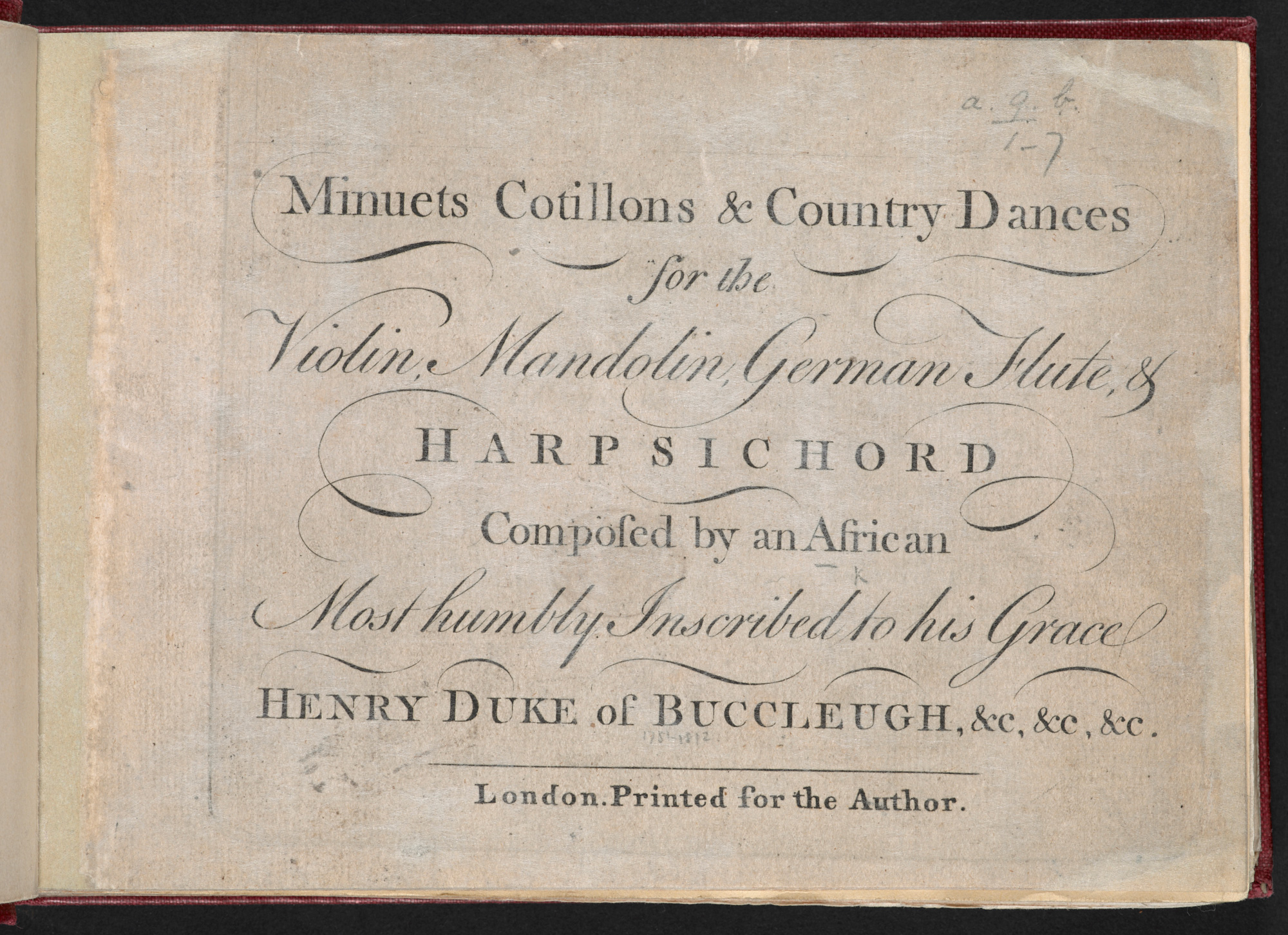

In addition to running a successful business, he composed music, two plays, and a treatise on musical theory. Though his plays and treatise do not survive, his music does:

This chapter concludes with a performance of some of his pieces.

Sancho was also a prolific letter writer, whose correspondence with a vast network of public figures, was published in 1782, two years following his death, prefaced by Jekyll’s short biography. Sancho’s letters provide a rare glimpse into the life of a prosperous black Englishman of the eighteenth century, a successful businessman, a passionate abolitionist, a lover of music and literature, a doting family man, and a keen observer of his time.

A Sampling from Sancho’s Letters:

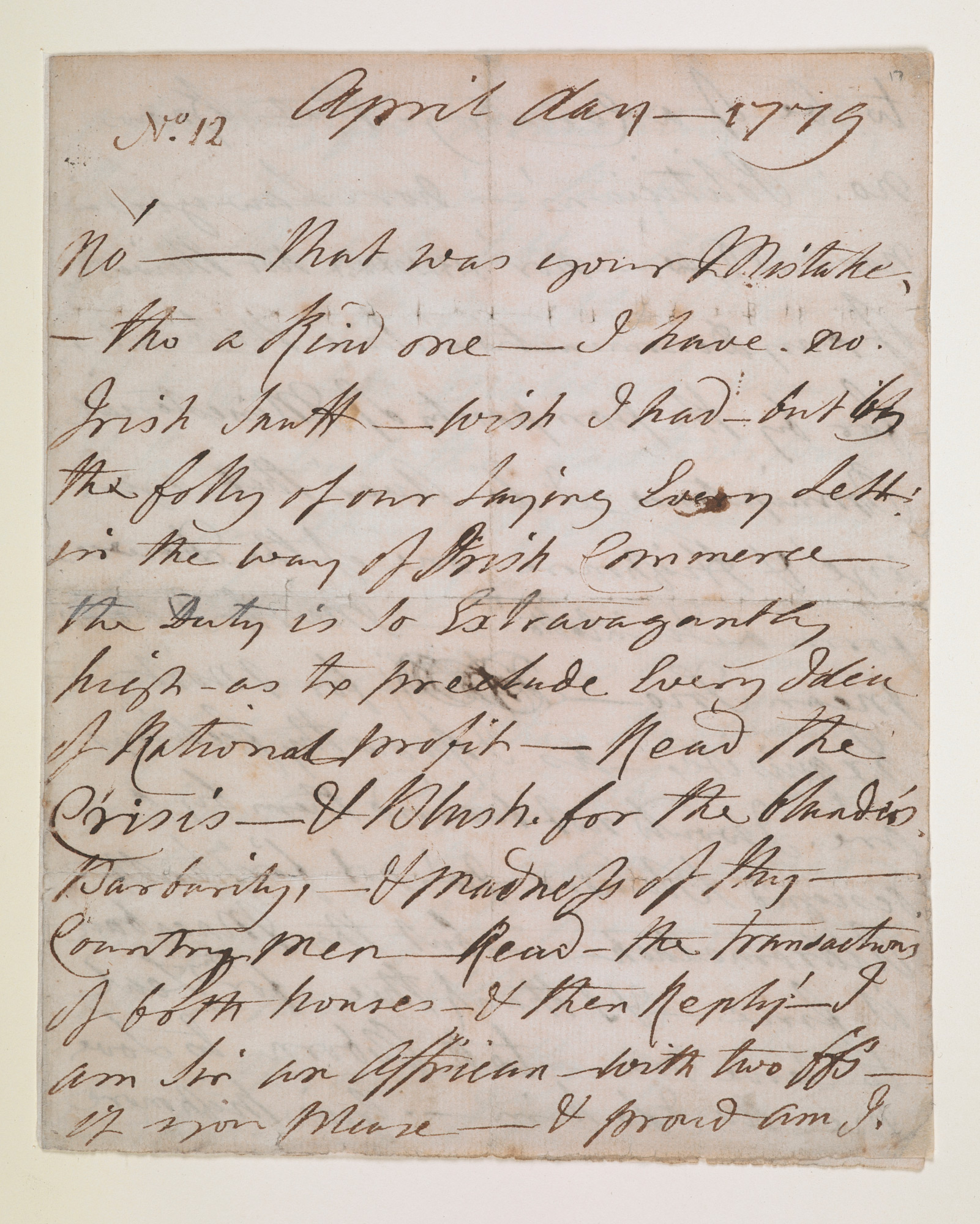

Sancho was proud of his African descent and repeatedly emphasized that he was a black man. In this page from some of the only surviving handwritten letters, he declares: “I am sir an Affrican–with two ffs–if you please-& proud am I to be of a country that knows no politicians–nor lawyers…nor Thieves.”

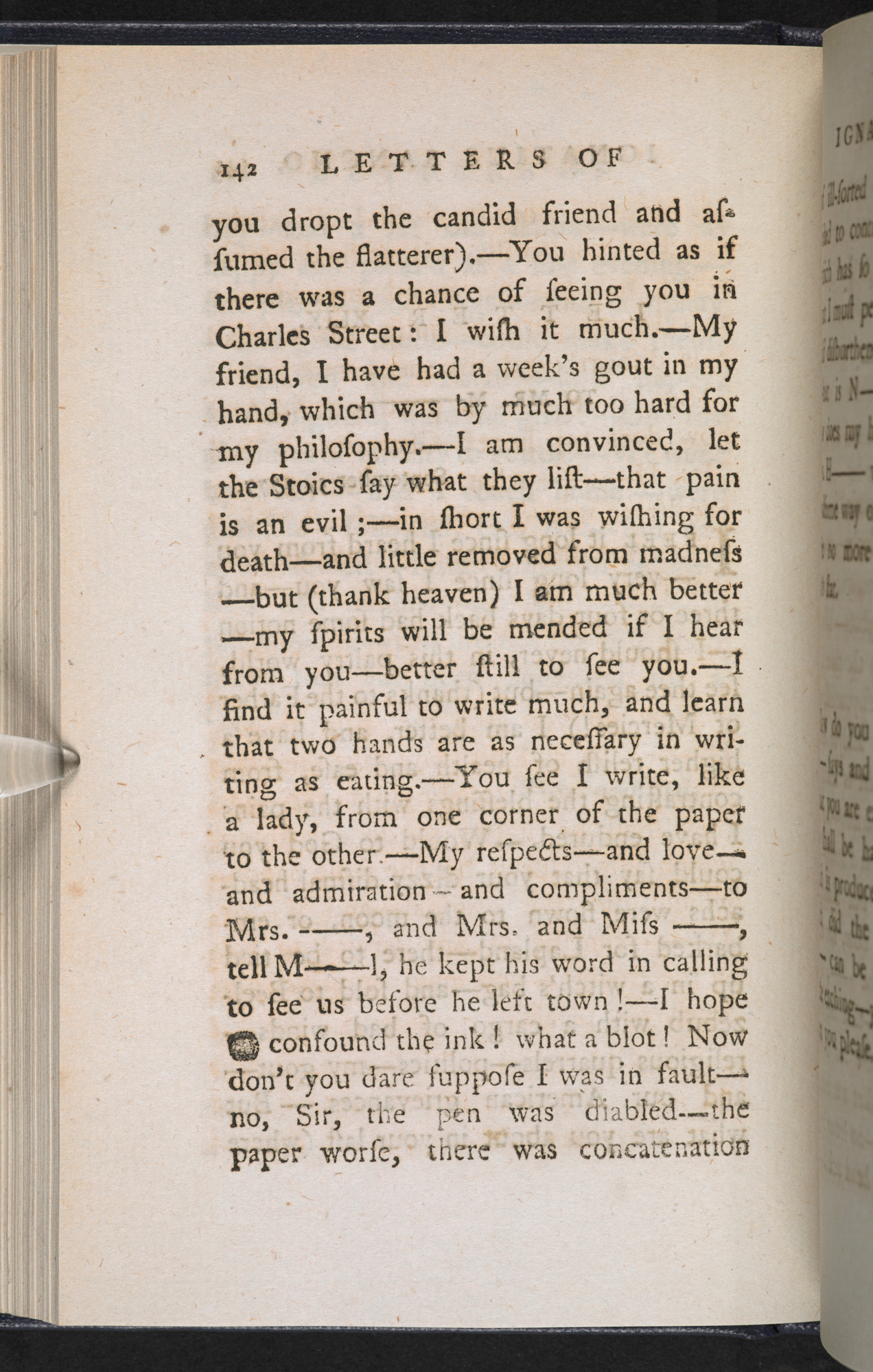

The page below captures the playfulness of Sancho’s writing, with his signature splattering of dashes all through the page. Sancho’s writing is full of digressions–rather like the writing of Lawrence Sterne, the novelist he so admired. At the bottom of the page we see him nattering his compliments and expressing his hope only to be distracted by an ink blot (which the publisher duly reproduces) “confound the ink blot! what a blot! Now don’t you dare suppose I was in fault–no, Sir, the pen was diabled–the paper worse, there was concatenation” and on he goes. What is “diabled”? One of Sancho’s many neologisms! This one from the French word for devil (diable).

Sancho’s best known correspondence was with novelist Lawrence Sterne, whom he urged in 1766 to “give half an hours attention to slavery,” confident that “that subject handled in your own manner, would ease the Yoke of many perhaps occasion a reformation throughout our Islands.” Sterne responded within the week, sharing the story of the “poor negro-girl” that he incorporated into the final volume of Tristram Shandy and deploring the state of affairs that make it “no uncommon thing … for one half of the world to use the other half of it like brutes, and then endeavor t make ’em so.”

Family Man

One thing that comes through loud and clear from even a casual perusal of Sancho’s letters is his deep and abiding love for his wife and children. Practically every one of his letters contains some reference to Mrs. Sancho–“Mrs. Sancho sends her best wishes”; “Mrs. Sancho says little–but her moistened eye expresses–that she feels your friendship”; “Mrs. Sancho desires her thanks may be joined with mine.” To one friend he writes: “Mrs. Sancho would send you some tamarinds [laxatives];–I do not know her reasons;–as I hate contentions, I contradicted not–but shrewdly suspects she thinks you want cooling.”

The following is one of many delightful tributes to friendship and family.

To Mrs. F–

Richmond, Oct. 20, 1769

I sent you a note in Mrs. Sancho’s name this day fortnight–importing that she would hope for the pleasure of seeing you at Richmond before the fine weather takes its leave of us:–neither hearing from nor seeing you–though expecting you every day–we fear that you are not well–or that Mr. F– is unhappily ill–in either case we shall be very sorry–but I will hope you are all well–and that you will return an answer by the bearer of this that you are so–and also when we may expect to have the pleasure of seeing you;–there is half a bed at your service–

My dear Mrs. Sancho, thank God! is greatly mended, Come, do come, and see what a different face she wears now–to what she did when you kindly proved yourself her tender, her assisting tender friend.–Come and scamper in the meadows with three ragged wild girls.–Come and pour the balm of friendly converse into the ear of my sometimes low-spirited love! Come, do come, and come soon, if you mean to see Autumn in its last livery.–

Several years later, Sancho frets as his wife nears the end of a difficult pregnancy. To one friend he writes on October 4:

On October 16: “Mrs. Sancho smiles in the pains which it has pleased Providence to try her with–and her belief in a better existence is her cordial drop.” And two days later: “pray God to send my dear Mrs. Sancho safe down and happily up–she makes the chief ingredient of my felicity–whenever my good friend marries–I hope he will find it the same with him.”

Following the birth, on October 20, he heaves a great sigh of relief:

TO MISS L—-.

Friday, Oct. 20, 1775.

IN obedience to my amiable friend’s request–I, with gratitude to the Almighty–and with pleasure to her–(I am sure I am right)–acquaint her, that

my ever dear Dame Sancho was exactly at half past one, this afternon, delivered of a–child.–Mrs. Sancho, my dear Miss I—-, is as well as can be expected–in truth, better than I feared she would be–for indeed she has been very unwell for this month past–I feel myself a ton lighter:–In the morning I was crazy with apprehension–and now I talk nonsense thro’ joy.–This plaguy scrawl will cost you I know not what–but it’s not my fault–’tis your foolish godson’s [i.e., the newly delivered baby]–who, by me, tenders his dutiful respects. I am ever yours to command, sincerely and affectionately,

Mentor

To young Jack Wingrave (1757-97), Sancho wrote in 1768:

To another youth:

You may safely conclude now, that you have not many friends in England–be it your study, with attention, kindness, humility, and industry, to make friends where you are–industry with good-nature and honesty is the road to wealth.

Before I conclude, let me, as your true friend, recommend seriously to you to make yourself acquainted with your Bible:–believe me, the more you study the word of God–your peace and happiness will increase the more with it.–Fools may deride you–and wanton youth throw out their frothy gibes;–but as you are not to be a boy all your life–and I trust would not be reckoned a fool–use your every endeavour to be a good man–and leave the rest to God.–

Your letters from the Cape, and one from Madeira’s, I received; they were both good letters–and descriptions of things and places.–I wish to have your description of the fort and town of Madrass–country adjacent–people–manner of living–value of money–religion–laws–animals–fashions–taste, &c.&c.–In short, write any thing–every thing–and above all, improve your mind with good reading–converse with men of sense, rather than with fools of fashion and riches–be humble to the rich–affable, open, and good-natured to your equals–and compassionately kind to the poor.–

I have treated you freely in proof of my friendship–Mrs. S–, under the persuasion that you are really a good man–sends her best wishes–when her handkerchief is washed, you will send it home–the girls wish to be remembered to you, and all to friend L–n.

The keys to success?

Study. Generosity. Industry. Honesty. Observation. Kindness.

Yes.

Composer

Sancho’s music performed:

Mastery Check:

- Name three instruments for which Sancho composed music.

- What business did Sancho pursue with his wife Anne?

- How would you characterize Sancho’s marriage?

- Which white novelist did Sancho persuade to join his crusade against slavery?

- What did Sancho spend his last shilling on during his wild and crazy days?

- How does Sancho’s writing resemble Lawrence Sterne’s?

- Name one of Sancho’s neologisms.

- How does an ink blot figure into Sancho’s writing?

- What, for Sancho, are the keys to success?

The Middle Passage was the stage of the triangular trade in which millions of Africans were forcibly transported to the New World as part of the Atlantic slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manufactured goods, which were traded for purchased or kidnapped Africans, who were transported across the Atlantic as slaves; the enslaved Africans were then sold or traded for raw materials, which would be transported back to Europe to complete the voyage.

Source: wikipedia