Chaucer’s Portraits: The Wife of Bath & Clerk

Now let’s turn to the plot of The Canterbury Tales. Following the eighteen-line opening we analyzed above, Chaucer identifies himself as one of those “folk” who “longen … to goon on pilgrimages.” We’re proceeding from here on with translations into Modern English, so keep in mind that Chaucer’s Middle English was way better!

Befell that, in that season, on a day

In Southwark, at the Tabard, as I lay

Ready to start upon my pilgrimage

To Canterbury, full of devout homage,

There came at nightfall to that hostelry

Some nine and twenty in a company

Of sundry persons who had chanced to fall

In fellowship, and pilgrims were they all

That toward Canterbury town would ride.

The rooms and stables spacious were and wide,

And well we there were eased, and of the best.

And briefly, when the sun had gone to rest,

So had I spoken with them, every one,

That I was of their fellowship anon,

And made agreement that we’d early rise

To take the road, as you I will apprise.

But none the less, whilst I have time and space,

Before yet farther in this tale I pace,

It seems to me accordant with reason

To inform you of the state of every one

Of all of these, as it appeared to me,

And who they were, and what was their degree,

And even how arrayed[1] there at the inn;

And with a knight thus will I first begin.

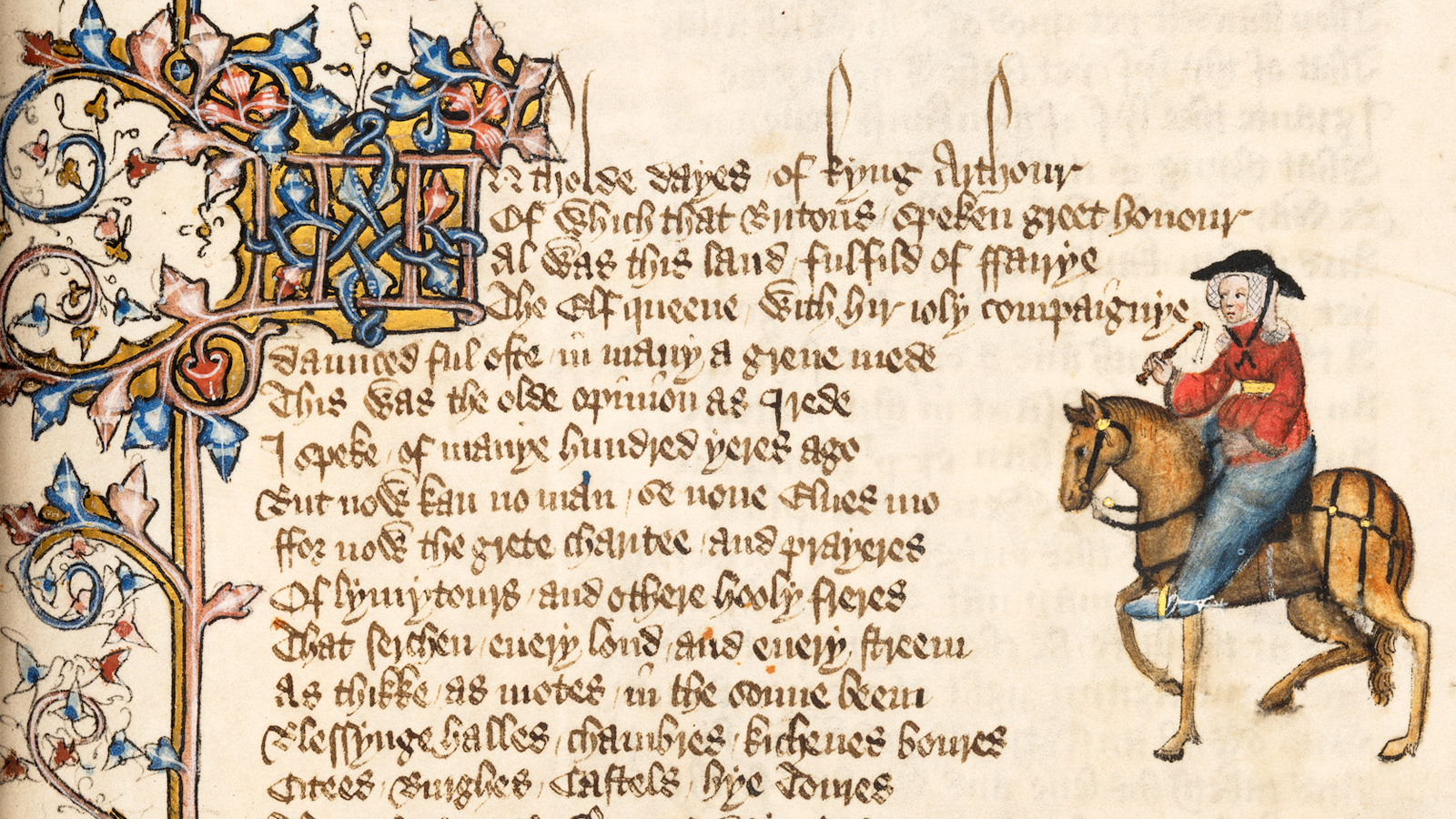

Chaucer proceeds to offer individual and group “portraits” of his twenty-nine pilgrims. His techniques of portraiture are diverse—sometimes he focuses on appearance, sometimes on character, sometimes on personal quirks, sometimes on professional practices. Below are two portraits: one of a Clerk, or student, studying at Oxford (England’s oldest university), the other of a Wife from Bath. Following Chaucer’s literary portraits, you will see how one medieval illustrator translated word into image in the so-called Ellesmere Chaucer, a gorgeous edition of the Canterbury Tales completed within a decade of Chaucer’s death in 1400. Compare the two renderings of the pilgrims: how faithfully did the Ellesmere artist render Chaucer’s description? Was the artist able to capture facets of the Pilgrims’ personality as well as their appearance? If so, how?

THE CLERK

A clerk from Oxford was with us also,

Who’d turned to getting knowledge, long ago.

As meagre was his horse as is a rake,

Nor he himself too fat, I’ll undertake,

But he looked hollow and went soberly.

Right threadbare was his overcoat; for he

Had got him yet no churchly benefice[2],

Nor was so worldly as to gain office.

For he would rather have at his bed’s head

Some twenty books, all bound in black and red,

Of Aristotle and his philosophy

Than rich robes, fiddle, or gay psaltery.

Yet, and for all he was philosopher,

He had but little gold within his coffer;[3]

But all that he might borrow from a friend

On books and learning he would swiftly spend,

And then he’d pray right busily for the souls

Of those who gave him wherewithal for schools.

Of study took he utmost care and heed.

Not one word spoke he more than was his need;

And that was said in fullest reverence

And short and quick and full of high good sense.

Pregnant of moral virtue was his speech;

And gladly would he learn and gladly teach.

Watch the video lecture below on the Clerk to find out what it was like to be a student in late-fourteenth-century England. Paying tuition was a challenge then, too, and the Clerk drew on a source of financial aid that isn’t available to most students today.

Mastery Check

- In what respects might a medieval student’s experience have resembled or differed from yours?

- How might a medieval student finance his education?

- What subjects would a medieval undergraduate have studied?

- What was Purgatory?

- What was “disputatio”?

THE WIFE OF BATH

There was a housewife come from Bath, or near,

Who- sad to say- was deaf[4] in either ear.

At making cloth she had so great a bent

She bettered those of Ypres and even of Ghent.

In all the parish there was no goodwife

Should offering make before her, on my life;

And if one did, indeed, so wroth was she

It put her out of all her charity.

Her kerchiefs were of finest weave and ground;

I dare swear that they weighed a full ten pound

Which, of a Sunday, she wore on her head.

Her hose were of the choicest scarlet red,

Close gartered, and her shoes were soft and new.

Bold was her face, and fair, and red of hue.

She’d been respectable throughout her life,

With five churched husbands[5] bringing joy and strife,

Not counting other company in youth;

But thereof there’s no need to speak, in truth.

Three times she’d journeyed to Jerusalem;[6]

And many a foreign stream she’d had to stem;

At Rome she’d been, and she’d been in Boulogne,

In Spain at Santiago, and at Cologne.

She could tell much of wandering by the way:

Gap-toothed[7] was she, it is no lie to say.

Upon an ambler easily she sat,

Well wimpled, aye, and over all a hat[8]

As broad as is a buckler or a targe;[9]

A rug was tucked around her buttocks large,

And on her feet a pair of sharpened spurs.

In company well could she laugh her slurs.

The remedies of love she knew, perchance,

For of that art she’d learned the old, old dance.

The following video lecture walks you through Chaucer’s portrait of the Wife of Bath.

Mastery Check:

- What cities and countries did the Wife visit during her pilgrimages?

- What does Chaucer tell us about the Wife of Bath’s hearing?

- What does the Wife of Bath look like?

Mastery Check:

- Who is Harry Bailly?

- What are the rules of the Canterbury storytelling contest?

- What criteria must the winning story have?

- What kinds of people are on the Canterbury pilgrimage?

- What kinds of stories do the Canterbury pilgrims tell?

- Who tells a story that parodies the Knight’s Tale?

The women with whom Chaucer was connected tended to be independent…..His wife Philippa had her own job and her own money, and this did not change after she had children. She lived in great households, and in her sister’s household far more than she lived with her husband. She moved in higher social circles than he did …. Agnes Chaucer, Geoffrey’s mother, had been a property owner in her own right. Cecily Champaigne sued him, in her own name, and it paid off…. Chaucer’s own daughter, by entering prestigious nunneries, was in fact put in a position to be in many ways more independent than a married woman, to live a comfortable and intellectually free life…. Her cousin became the abbess at Barking, which meant becoming a major businesswoman and manager. In London more generally, Chaucer would have known female artisans, femmes sole who traded in their own right, guildswomen, and property owners. His life gave him multiple experiences of women as thinking and independent beings, strong women, even though they underwent all kinds of legal and social constraints. There is no evidence that Chaucer ever acted as a controlling patriarch within his family, or that he had any family or intimate experience of women who lived under the direct and exclusive financial and spatial control of men. (Marion Turner, Chaucer: A European Life [Oxford University Press, 2019], pp. 212-13)

Mastery Check:

- What kinds of women would Chaucer have come into contact with during his life?

- What opportunities did medieval women have?

- i.e., how they were dressed. ↵

- A benefice was an appointment within the Church, complete with a stipend and therefore financial security. ↵

- coffer: a portable container for money or valuables. ↵

- Chaucer explains the Wife of Bath's partial deafness elsewhere in the Canterbury Tales. ↵

- In other words, she was legally married five times. ↵

- Here and further below, Chaucer relates the Wife's extensive pilgrimages, which should also serve as a sign of her wealth. ↵

- Women who possessed a gap in their front teeth (also called "diastema") were frequently associated with lustfulness in the Middle Ages. ↵

- A "wimple" was a cloth head-covering. Here Chaucer notes that the Wife wore a fine wimple with a nice hat over it (for good measure). ↵

- A "buckler" and a "targe" were both types of shields. ↵

The Tabard was a historic inn that stood on the east side of Borough High Street in Southwark. The hostelry was established in 1307 and stood on the ancient thoroughfare that led south from London Bridge to Canterbury and Dover. It was built for the Abbot of Hyde who purchased the land to construct a place to stay for himself and his ecclesiastical brethren when on business in London.

The Tabard was also famous for accommodating people who made the pilgrimage to the Shrine of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral, and Geoffrey Chaucer mentions it in his 14th Century work The Canterbury Tales. (source: Wikipedia)