Alexander Pope: The Culture of Things

Alexander Pope (1688-11744)

Like Margaret Cavendish, Alexander Pope was a brilliant eccentric. His creativity is evinced not only in his writings, which cover so many literary genres, but in his approach to the business of publication. This video lecture will tell you a bit about this innovator and introduce you to his masterful “fake apology,” The Rape of the Lock.

Mastery Check

- Why didn’t Pope get his university degree?

- What disabilities did Pope live with?

- Where do we find the tortoise and the elephant in Rape of the Lock?

- What is the relationship between objects, people, and values in Rape of the Lock?

The Rape of the Lock

Pope’s Rape of the Lock blends brilliance with nastiness to produce an ingenious example of the all too common non-apology: “Can’t you take a joke?” The poem was conceived in response to a quarrel that broke out between two prominent Catholic families when Robert, Baron Petre, snipped a lock of Arabella Fermor’s hair. Fermor was furious at the liberty, and a mutual friend asked Pope to intervene and restore harmony. He does so with a mock-epic that makes light of the theft of the lock.

Sampling The Rape of the Lock

Say what strange motive, Goddess! Could compel

A well-bred lord t’assault a gentle belle?

Oh say what stranger cause, yet unexplored,

Could make a gentle belle reject a lord?

Note that for Pope a belle rejecting a lord is stranger than a lord assaulting a belle!

To narrate this strangeness, Pope draws upon the conventions of epic. In Pope’s time, “rape” meant not only sexual assault but also any forcible seizure of something (a lock of hair, for example) belonging to another. The title, Rape of the Lock, while explicitly referring to Belinda’s hair, implicitly invokes the famous rape of Helen, which launched the Trojan war. Helen’s “raptus” was an event abundantly commemorated in art of the period.

By comparison to the sexual assault and abduction of a woman, the snipping of a lock of hair might seem trivial. However, the rape of Helen had become such a commonplace in art that it was itself trivialized, a subject fit, for example, for portraying on a lady’s fan:

The Rape of the Lock, like many a classical epic, begins in medias res, that is, in the middle of things. Pope’s Helen-equivalent, the “gentle belle” Belinda, is troubled by dreams auguring some terrible danger. Such ambiguous portents are among the staples of epics. Awakened by her dog Shock licking her face, she forgets the dream and readies herself for the day. Pope describes Belinda’s dressing table as a kind of altar and Belinda herself as a goddess attended by her priestess, her maid, Betty. This scene is the equivalent of the scenes the arming-of-the-hero episodes common in epic. About Belinda flit invisible sprites called Sylphs, whose business it is to guard the honor of young ladies. Note Pope’s evocation of the British empire in this passage.

Can you spot the tortoise and the elephant?

And now, unveil’d, the Toilet˚ stands display’d, dressing-table

Each Silver Vase in mystic Order laid.

First, rob’d in White, the Nymph intent adores

With Head uncover’d, the Cosmetic Pow’rs.

A heav’nly Image in the Glass appears,

To that she bends, to that her Eyes she rears;

Th’ inferior Priestess˚, at her Altar’s side, presumably Belinda’s maid Betty

Trembling, begins the sacred Rites of Pride.[i]

Unnumber’d Treasures ope˚ at once, and here open

The various Off’rings of the World appear;

From each she nicely culls with curious Toil,

And decks the Goddess with the glitt’ring Spoil.

This Casket India’s glowing Gems unlocks,

And all Arabia breathes from yonder Box.

The Tortoise here and Elephant unite,

Transform’d to Combs, the speckled and the white.

Here Files of Pins extend their shining Rows,

Puffs, Powders, Patches, Bibles, Billet-doux.

Now awful˚ Beauty puts on all its Arms; awe-inspiring

The Fair each moment rises in her Charms,

Repairs her Smiles, awakens ev’ry Grace,

And calls forth all the Wonders of her Face;

Sees by Degrees a purer Blush arise,

And keener Lightnings quicken in her Eyes.

The busy Sylphs surround their darling Care;

These set the Head, and those divide the Hair,

Some fold the Sleeve, while others plait the Gown;

And Betty’s prais’d for Labours not her own.

Belinda’s physical assets include two lovely locks of hair. The “adventurous Baron” admired these locks and hoped to acquire one. The question: should he proceed by force or fraud? (Note the echo of Paradise Lost, when Satan asks the devils whether they should proceed by war or guile?)

This Nymph, to the Destruction of Mankind,

Nourish’d two Locks, which graceful hung behind

In equal Curls, and well conspir’d to deck

With shining Ringlets her smooth Iv’ry Neck.

Th’ Adventrous Baron the bright Locks admir’d,

He saw, he wish’d, and to the Prize aspir’d:

Resolv’d to win, he meditates the way,

By Force to ravish, or by Fraud betray;

For when Success a Lover’s Toil attends,

Few ask, if Fraud or Force attain’d his Ends.

Like some epic hero on the eve of a battle, the baron prostrates himself to his gods before an altar decked with French romances the trophies of former loves. He burns these offerings in a flame kindled with love letters (billet-doux) and amorous sighs. The “Powers” indicate that they will grant at least some of what he wants:

For this, e’re Phoebus˚ rose, he had implor’d the sun

Propitious Heav’n, and ev’ry Pow’r ador’d,

But chiefly Love—to Love an Altar built,

Of twelve vast French Romances, neatly gilt.

There lay three Garters, half a Pair of Gloves;

And all the Trophies of his former Loves.

With tender Billet-doux he lights the Pyre,

And breathes three am’rous Sighs to raise the Fire.

Then prostrate falls, and begs with ardent Eyes

Soon to obtain, and long possess the Prize:

The Pow’rs gave Ear, and granted half his Pray’r,

The rest, the Winds dispers’d in empty Air.

This is obviously the danger Belinda dreamed of. Her guardian sylph, Ariel, is aware of this danger (it was he, indeed, who troubled her dream)—but he doesn’t know what it is. He arranges an army of sylphs about Belinda’s person, warning them to be prepared for whatever comes. Note how in this extract from Ariel’s rallying cry to the sylphs, Pope yokes the trivial and the momentous:

This Day, black Omens threat the brightest Fair

That e’er deserv’d a watchful Spirit’s Care;

Some dire Disaster, or˚ by Force, or Slight, either

But what, or where, the Fates have wrapt in Night.

Whether the Nymph shall break Diana’s Law,

Or some frail China Jar receive a Flaw,

Or stain her Honour, or her new Brocade,

Forget her Pray’rs, or miss a Masquerade,

Or lose her Heart, or Necklace, at a Ball;

Or whether Heav’n has doom’d that Shock must fall.

Haste then ye Spirits! to your Charge repair;

The flutt’ring Fan be Zephyretta’s Care;

The Drops˚ to thee, Brillante, we consign; earrings (presumably diamonds)

And Momentilla, let the Watch be thine;

Do thou, Crispissa, tend her fav’rite Lock;

Ariel himself shall be the Guard of Shock.

At a social gathering at Hampton Court, Baron and Belinda match wits in the popular card game ombre (a trick-taking game related to bridge). Pope describes the game as a battle, which Belinda wins by trumping the Baron’s ace with her king. As she triumphs, however, the Baron sees an opportunity: his ally Clarissa slips him a pair of scissors and he snips Belinda’s lock.

Ariel sees the blades coming, but cannot intervene, for he perceives that Belinda is harboring thoughts of a lover.

Just in that instant, anxious Ariel sought

The close Recesses of the Virgin’s Thought;

As on the Nosegay˚ in her Breast reclin’d, fragrant small bouquet

He watch’d th’ Ideas rising in her Mind,

Sudden he view’d, in spite of all her Art,

An Earthly Lover lurking at her Heart.

Amaz’d, confus’d, he found his Pow’r expir’d,

Resign’d to Fate, and with a Sigh retir’d.

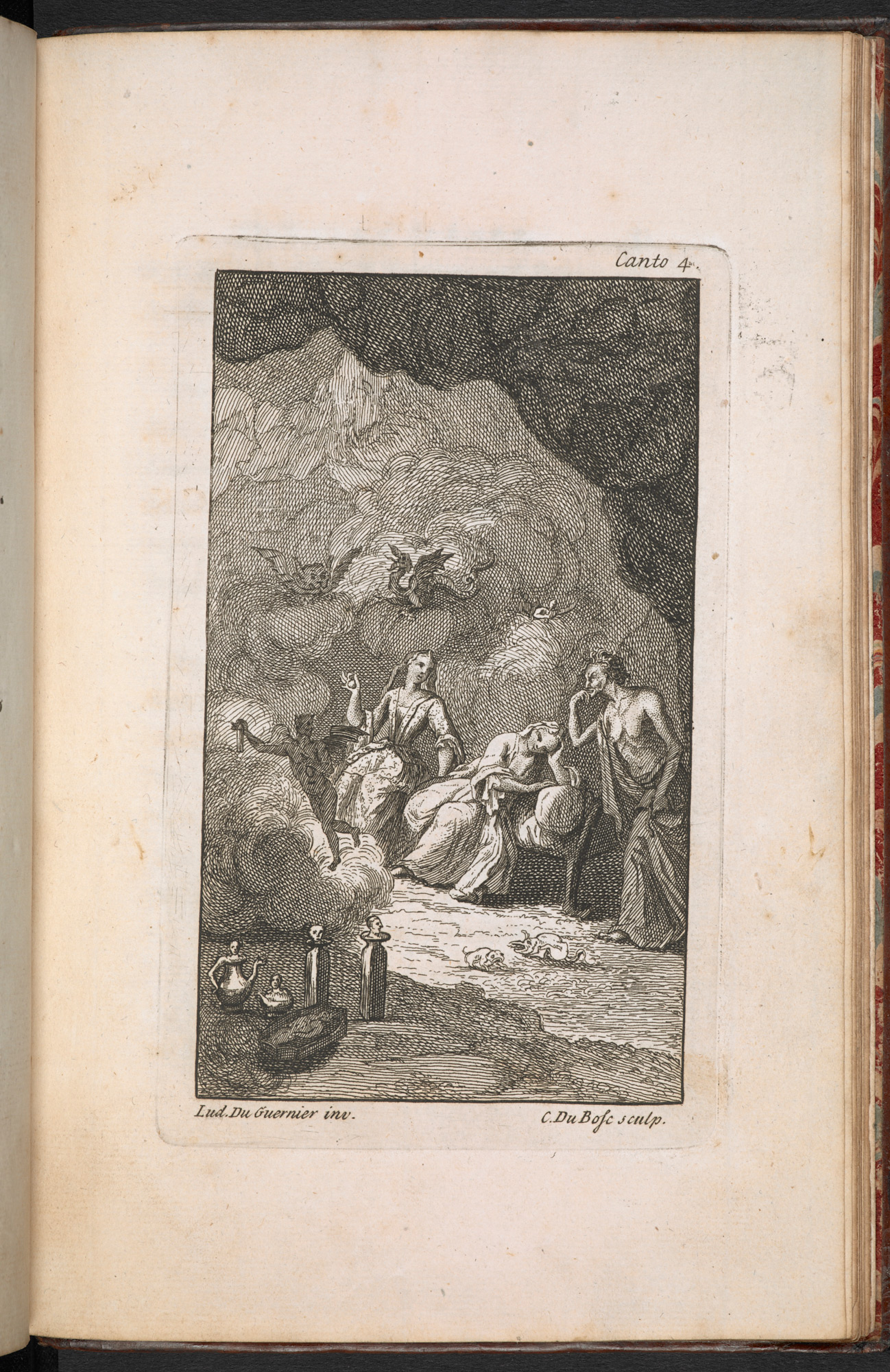

Belinda is apparently not as pure as Ariel had assumed. The lock is clipped, and forthwith, a gnome by the name of Umbriel heads off to the Cave of Spleen, bent on making mischief.

The Cave of Spleen, Pope’s equivalent of the Underworld in classical epics, is a surreal world in which humans have been transformed into objects:

Unnumber’d Throngs on ev’ry side are seen

Of Bodies chang’d to various Forms by Spleen.

Here living Teapots stand, one Arm held out,

One bent; the Handle this, and that the Spout:

A Pipkin˚ there like Homer’s Tripod walks; a small earthenware pot

Here sighs a Jar, and there a Goose-pie talks;

Men prove with Child, as pow’rful Fancy works,

And Maids turn’d Bottles, call aloud for Corks.

From the goddess who presides over this strange netherworld he obtains what he wants:

A wondrous Bag with both her Hands she binds,

Like that where once Ulysses held the Winds;

There she collects the Force of Female Lungs,

Sighs, Sobs, and Passions, and the War of Tongues.

A Vial next she fills with fainting Fears,

Soft Sorrows, melting Griefs, and flowing Tears.

Umbriel releases the contents of the bag over Belinda and havoc ensues. Belinda attacks the Baron with a bodkin, thundering, “Restore the lock!”

Too late, though.

The lock has risen to the heavens, “a sudden star” to “inscribe Belinda’s name” for all eternity.

As you can see from the extracts you read, Pope’s Rape of the Lock is saturated with references to fine things, tributes to the consumerism of his world. You might well ask whether Belina and the Baron are characters or merely the expressions of their possessions. Desires without substance. Is the Baron’s seizure of Belinda’s lock any more significant than her king of hearts’ seizure of his jack of diamonds in the game of ombre?

Mastery Check

- What are some of the conventions of epic that Pope invokes in Rape of the Lock?

- What is ombre and how does it figure into the Rape of the Lock?

- What ultimately happens to Belinda’s lock?

- Why couldn’t Ariel protect Belinda’s lock from the baron’s scissors?

- What kind of creatures do we find in the Cave of Spleen?