10 British of African Descent: A Gallery

“I immediately after observed a picture hanging in the room, which appeared constantly to look at me, I was still more affrighted, having never seen such things as these before.” (Equiano, Interesting Narrative)

Ignatius Sancho

You’ve already seen this portrait of Sancho in an earlier chapter, but now let’s take a closer look at it as portraiture. The portrait was painted by renowned artist Thomas Gainsborough in 1768, when Sancho was still in the service of the Duke and Duchess of Montagu. Scholar and museum curator Reyahn King notes that though the half-length portrait would have been “appropriate” for a servant, Sancho is otherwise represented not as a servant but as a “respectable Englishman.” Unlike other artists, who often lightened the skin tone of their Black subjects, Gainsborough used a “reddish base” and “chocolate tone” to accentuate the rich darkness of Sancho’s face and create a portrait “warm in tone as well as feeling.” Sancho, who always emphasized his identity as an “African,” would doubtless have approved.[1]

Phillis Wheatley

Born in West Africa in 1753, Phillis Wheatley was sold into slavery when she was about seven years old and transported to America. There she was purchased by a wealthy merchant family, Wheatleys of Boston, who educated her and encouraged her writing. In 1773, she visited London to seek support for the publication of her collected poems. The expedition was successful: Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, published in London that year, made her the first published African-American poet. Her admirers included Ignatius Sancho, who praised her poetry and excoriated “her master–if she is still a slave.” Wheatley was emancipated in 1773, soon after her book was published. In 1784, at the age of 31, she died, impoverished and forgotten.

Phillis Wheatley, frontispiece to her Poems on Various Subjects (1773)

Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay

Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay (1761-1804) was the daughter of Sir John Lindsay and Maria Bell, an African woman enslaved in the West Indies. Lindsay entrusted her upbringing to his uncle, William Murray, first Earl of Mansfield, and his wife Elizabeth. The Murrays, who were childless, were also bringing up another great-niece, Lady Elizabeth Murray. The portrait below represents the cousins. Both ladies are richly dressed, though in contrast to Elizabeth’s conventional garb, Dido is clearly wearing an exotic costume.

Belle was well educated and much loved by her great-uncle, who, upon his death, confirmed her status as a free woman and bequeathed her a sum of £500 along with an annuity of £100. Lindsay’s obituary praised Belle as one “whose amiable disposition and accomplishments have gained her the highest respect from all his Lordship’s relations and visitants.”

In his office as Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Lord Mansfield ruled that James Somerset, an enslaved person who while in England had escaped from his master and was recaptured, could not be removed from the country for sale in Jamaica. “The black must be discharged,” he decreed. Abolitionists hailed his ruling as ending slavery in England–though it in fact did no such thing (Somerset v. Stewart). Critics of the decision blamed Belle’s influence.

Ottobah Cugoano

Born circa 1757 in what is now Ghana, Ottobah Cugoano was kidnapped at the age of thirteen and sold into slavery. After obtaining his freedom, he became a prominent member of the black community in London and a powerful voice in the anti-slavery movement. His Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1787), the first testimony against slavery by a black Englishman, was printed three times, translated into French, and abridged as Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery (1791). It was radical not only for its indictment of slavery but for its attack on colonialism. The image below is thought to represent Cugoano with his employers, artists Richard and Maria Cosway.

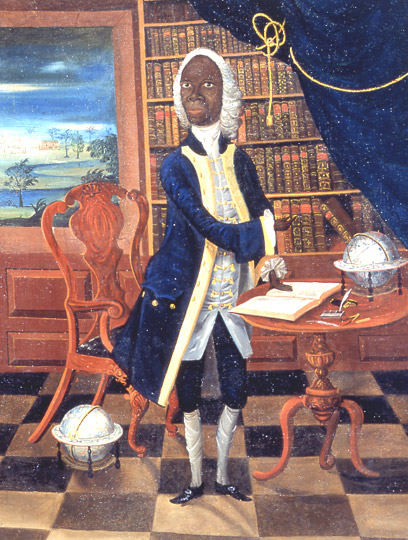

Francis Williams

Francis Williams (ca. 1700-1770) was born to free black Jamaicans. Propertied and wealthy, they saw that their children had a good education. Williams may have studied at Cambridge University. In 1723, he became a British citizen. A poet and scholar, Williams established a free school for Blacks in Jamaica. (At the time, most free schools were only for white children.). There he taught math, Latin, reading and writing.

Williams’s success excited resentment that turned violent. White planter William Brodrick first insulted, then struck Williams in 1724; Williams struck back. When he successfully argued that, as a free black man, he could not be tried for striking a white man in self-defense, the all-white ruling Assembly secured legislation making it a crime for a black to strike a white under any circumstances.

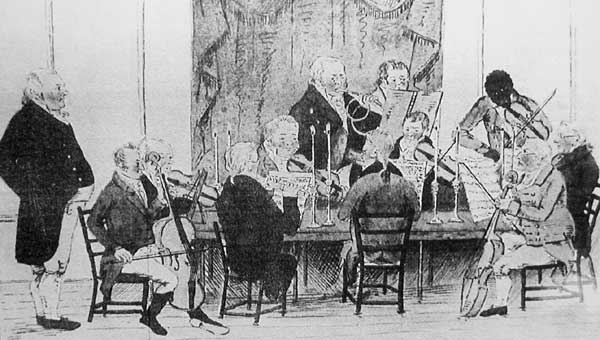

George Bridgetower

Born in Poland, George Bridgetower (1778-1860), a violinist, composer, and music teacher, moved to England when he was a boy and lived much of his life there. A child prodigy, Bridgetower attracted the attention of the Prince George (later George IV), who funded his further education.

Joseph Antonio Emidy

Joseph Antonio Emidy (1775-1835) was born in Guinea and enslaved as a child by the Portuguese. After spending time in Brazil, he came to Portugal and was freed. An acclaimed violinist, he played for the Lisbon Opera before he being kidnapped and forced to serve in the British navy during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1799, he settled in Cornwall, where he taught and composed music and led the Truro Philharmonic Orchestra.

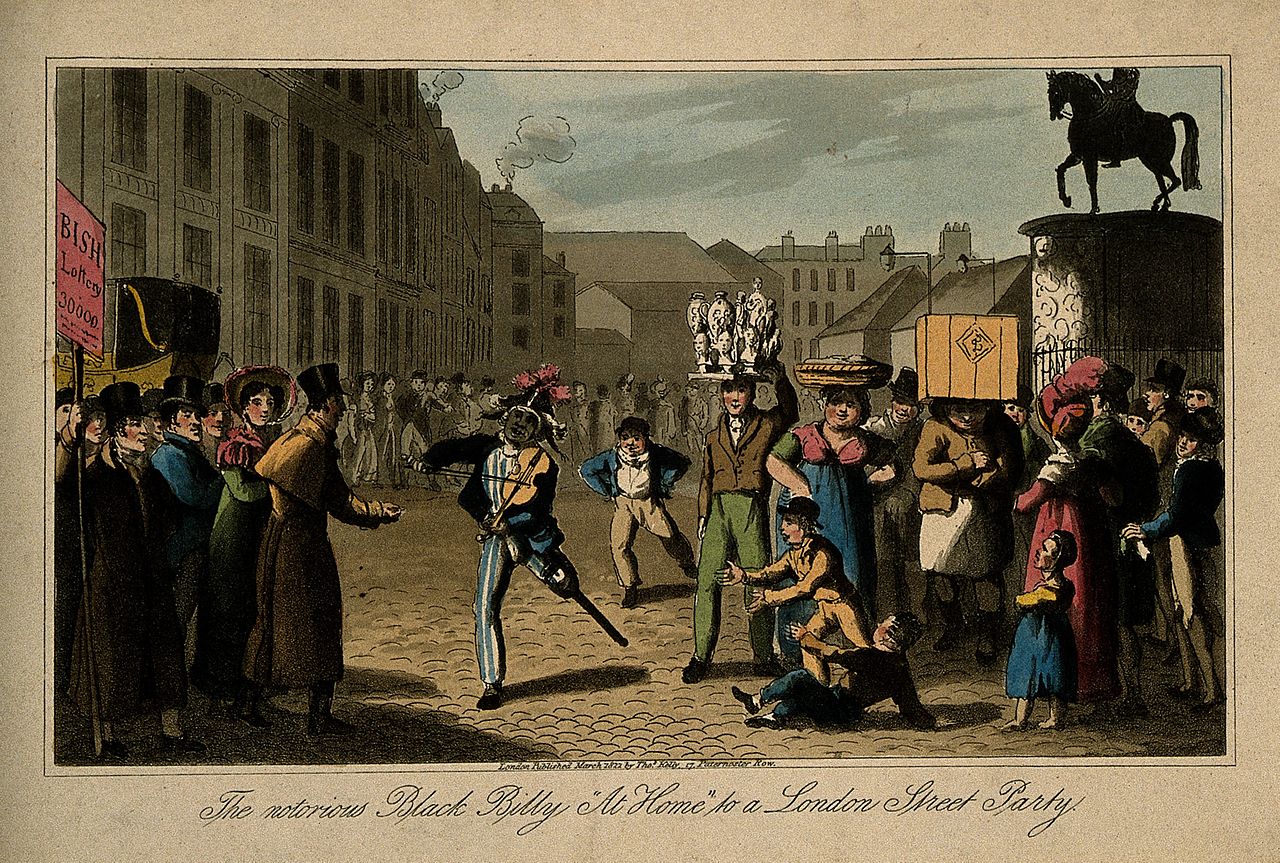

Billy Waters

Billy Waters (1778-1823), formerly enslaved, became a celebrity street performer in London.

Unknown

This portrait, once thought to be of Equiano, in the words of Reyahn King, “bears mute testimony to the presence in Britain of black individuals who were of sufficient status to have their portraits painted even if we do not know who they are today.” King adds, “It possesses the disturbing forthrightness and presence which Equiano himself noticed the first time he saw a portrait in 1756.”[2]

Mastery Check

- This denizen of colonial Boston was the first published African-American poet.

- He established a free school for blacks in Jamaica.

- Well educated and praised for her “amiable disposition and accomplishments.”

- What markers indicate that Thomas Gainsborough painted Sancho not as a servant but as a respectable Englishman?

- A celebrity street performer in London.

- Name two black composers of the eighteenth century.

an English portrait and landscape painter, draughtsman, and printmaker. Along with his rival Sir Joshua Reynolds,[1] he is considered one of the most important British artists of the second half of the 18th century.[2] He painted quickly, and the works of his maturity are characterised by a light palette and easy strokes. Despite being a prolific portrait painter, Gainsborough gained greater satisfaction from his landscapes.[3] He is credited (with Richard Wilson) as the originator of the 18th-century British landscape school. Gainsborough was a founding member of the Royal Academy.

(source: Wikipedia)

A judgment of the English Court of King's Bench in 1772 relating to the right of an enslaved person on English soil not to be forcibly removed from the country and sent to Jamaica for sale.

(source: Wikipedia)