Poet of the Natural World

The Poet’s Persona

The primary text readings for this bundle will offer you a window into the mind and literary achievement of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1623–1673). Cavendish was a quintessential “Renaissance woman”; she was a philosopher, a natural scientist, a playwright, and a poet. She is widely considered the chief architect of a new genre of writing: science fiction. Her oeuvre also reveals her deep fascination with living things and natural processes—a progenitor of what we would call eco-poetry today. Below you will have the opportunity to appreciate Cavendish’s poetry, which speaks to the deeply entwined relationship between humanity and the natural world.

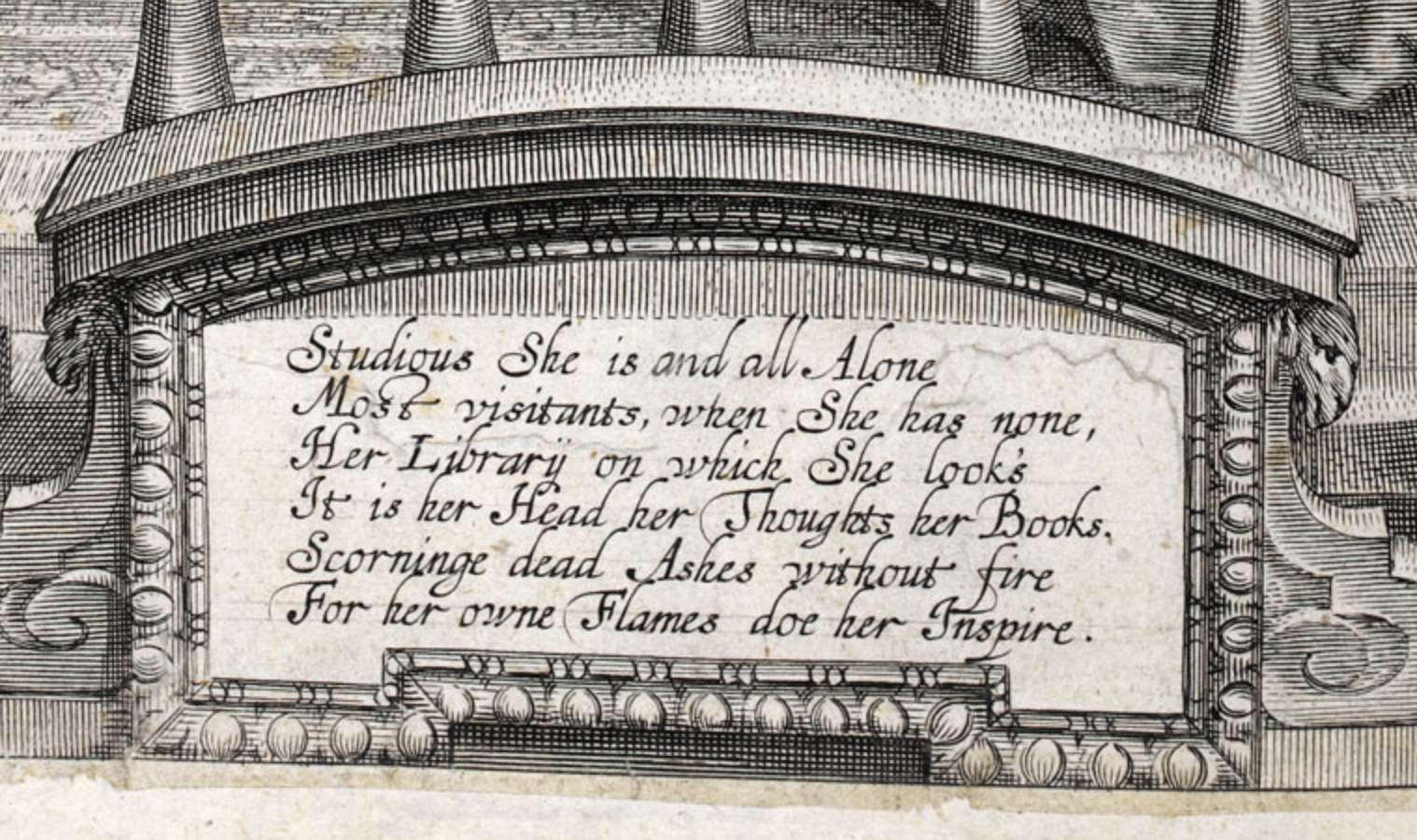

As Cavendish invigorated her literary world with her unique contributions in poetry and prose, she simultaneously maintained an expertly crafted public persona. First, she resisted social restraints placed on women’s writing by publishing under her own name. In her own personal and professional life, Cavendish successfully navigated two worlds—as a writer in her family as well as a solitary poet. You can see Cavendish’s (dual) authorial persona on full display in the engravings below. Each piece represents Cavendish in her “element”—an aristocratic woman engaged in the literacy of her family as well as a luminary, alone.

Thus in this Semy-Circle, wher they Sitt,

Telling of Tales of pleasure & of witt,

Heer you may read without a Sinn or Crime,

And how more innocently pass your tyme.

Highlight the text below for the answer!

Studious She is and all Alone

Most visitants, when She has none,

Her Library on which She looks

It is her Head her Thoughts her Books.

Scorninge dead Ashes without fire

For her own Flames doe her Inspire.

A Medley of Cavendish’s Eco-Poetry

Of the Theam° of Love theme

O Love, how thou art tired out with Rblme°! rhyme

Thou art a Tree whereon all Poets climbe;

And from thy branches every one takes some

Of thy sweet fruit, which feeds upon.

But now thy Tree is left so bare, and poor°, lacking

That they can hardly gather one Plumb° more plum

Deaths endeavour to hinder, and obstruct Nature

WHen Death did heare what Nature did intend,

To hinder her he all his force did bend[1].

But finding all his forces were too weake,

He alwaies° strives the Thread of life to breake: all ways

And strives to fill the Minde with black despaire,

Let’s it not rest in peace[2], nor free from care;

And since he cannot make it dye°, he will die

Send griefe, and sorrow to torment it still.

With grievous paines the Body he displeases,

And bindes it hard with chaines of strong diseases.

His Servants, Sloth, and Sleep, he doth imploye°, employ

To get halfe of the time before they dye:

But Sleep, a friend to Life, oft disobeyes

His Masters will, and softly downe her lay’s

Upon their weary limbs[3], like Birds in nest

And gently locks their senses up in rest.

Earths Complaint[4]

O Nature, Nature, hearken to my Cry,

Each [minute] wounded am, but cannot dye.

My Children which I from my Womb did beare,

Do dig my Sides, and all my Bowels teare:

Do plow deep Furroughs in my very Face,

From Torment, I have neither time, nor place[5].

No other Element is abus’d,

Nor by Man-kind so is us’d°. used

Man cannot reach the Skies to plow, and sow,

Nor can they, or mark the Stars to grow.

But they are still as Nature first did plant,

Neither Maturity, nor Growth they want°. lack

They never dye, nor do they yeild° their place give up

To younger Stars, but still run their owne Race.

The Sun doth never groane° young Suns to beare, lament

For he himselfe is his owne Son, and Heire.

The Sun just in the Center sits, as King,

The Planets round about incircle him.

The slowest Orbes over his Head turne slow,

And underneath, the Planets go.

Each severall° Planet, severall measures take, individual

And with their Motions they sweet Musick make.

Thus all the Planets round about him move,

And he returnes° them Light for their kind Love. repays

A Dialogue between an Oake, and a Man cutting him downe

Oake.

WHY cut you off my Bowes, both large, and long,

That keepe you from the heat, and scortching° Sun scorching

And did refresh your Limbs from sweat?

From thundring Raines I keepe you free, from Wet;

When on my Barke your weary head would lay,

Where quiet sleepe did take all Cares away.

The whilst[6] my Leaves a gentle noise did make,

And blew coole Winds, that you Aire night° take. might

Besides, I did invite the Birds to sing,

That their sweet voice might you some pleasure bring.

Where every one did strive to do their best,

Oft chang’d their Notes, and strain’d their tender Breast.

In Winter time, my Shoulders broad did hold

Off blustring° Stormes, that wounded with sharpe Cold. blowing

And on my Head the [Flakes] of snow did fall,

Whilst you under my Bowes free from all.

And will you thus requite° my Love, Good Will, return

To take away my Life, and kill?

For all my Care, and Service I have past,

Must I be cut, and laid on Fire at last?

And thus true Love you cruelly have slaine,

Invent alwaies° to torture me with paine. all ways

First you do peele my Barke, and flay my Skinne,

Hew° downe my Boughes, so chops off every Limb. cut

With Wedges you do peirce my Sides to wound,

And with your Hatchet knock me to the ground.

I mine’d shall be in Chips[7] and peeces small,

And thus doth Man reward good Deeds withall.° besides

Man.

Why grumblest thou, old Oake, when thou hast stood

This hundred yeares, as King of all the Wood.

Would you for ever live, and not resigne

Your Place to one that is of your owne Line?

Your Acornes young, when they grow big, and tall,

Long for your Crowne, and wish to see your fall;

Thinke every minute lost, whilst you do live,

And grumble at each Office you do give.

Ambitien° flieth high, and is above ambition

All sorts of Friend-ship strong, or Natur all Love.

Besides, all Subjects they in Change delight,

When Kings grow Old, their Government they slight:

Although in ease, and peace, and wealth do live,

Yet all those happy times for Change will give.

Growes discontent, and Factions still do make;

What Good so ere he doth, as Evill take.

Were he as wise, as ever Nature made,

As pious, good, as ever Heaven [saved]:

Yet when they dye, such Joy is in their Face,

As if the Devill had gone from that place.

With Shouts of Joy they run a new° to Crowne, again

Although next day they strive to pull him downe.

Why, said the Oake, because that they are mad°, insane

Shall I rejoyce, for my owne Death be glad?

Because my Subjects all ingratefull° are, ungrateful

Shall I therefore my health, and life impaire.

Good Kings governe justly, as they ought,

Examines not their Humours, but their Fault.

For when their Crimes appeare, t’is time to strike,

Not to examine Thoughts how they do like.

If Kings are never lov’d, till they do dye,

Nor to live, till in the Grave they lye:

Yet he that loves himselfe the lesse, because

He cannot get every mans high applause:

Shall by my Judgment be condemn’d to weare,

The Asses° Eares, and burdens for to beare. donkey’s

But let me live the Life that Nature gave,

And not to please my Subjects, dig my Grave.

Man.

But here, Poore Oake, thou liv’st in Ignorance,

And never seek’st thy Knowledge to advance.

I’le cut the downe[8], ’cause Knowledge thou maist° gaine, may

Shalt be a Ship, to traffick° on the Maine: sail

There shalt thou swim, and cut the Seas in two,

And trample downe each Wave, as thou dost go.

Though they rise high, and big are sweld° with pride, swollen

Thou on their Shoulders broad, and Back, shalt ride:

Their lofty Heads shalt bowe, and make them stoop,

And on their Necks shalt set thy steddy° Foot: steady

And on their Breast thy Stately Ship shalt beare,

Till thy Sharpe Keele the watry Wombe doth teare.

Thus shalt thou round the World, new Land to find,

That from the rest is of another kind.

Oake.

O, said the Oake, I am contented well,

Without that Knowledge, in my Wood to dwell.

For I had rather live, and simple be,

Then° dangers run, some new strange Sight to see. than

Perchance my Ship against a Rack° may hit; rock

Then were I strait in sundry° peeces split. various

Besides, no rest, nor quiet I should have,

The Winds would tosse me on each troubled Wave.

The Billowes rough will beat on every side,

My Breast will ake° to swim against the Tide. ache

And greedy Merchants may me over-fraight°, overload

So should I drowned be with my owne weight.

Besides with Sailes, and Rapes° my Body tye, ropes

Just like a Prisoner, have no Liberty.

And being alwaies wet, shall take such Colds,

My Ship may get a Pase[9], and leake through holes.

Which they to mend, will put me to great paine,

Besides, all patch’d, and peec’d°, I shall remaine. in pieces

I care not for that Wealth, wherein the paines,

And trouble, is farre greater then the Gaines.

I am contented with what Nature gave,

I not Repine°, but one poore wish would have, complain

Which is, that you my aged Life would save.

Man.

To build a Stately House I’le cut thee downe,

Wherein shall Princes live of great renowne.

There shalt thou live with the best Companie,

All their delight, and pastime thou shalt see.

Where Playes, and Masques, and Beauties bright will shine,

Thy Wood all oyl’d° with Smoake of Meat, and Wine. oiled

There thou shalt heare both Men, and Women sing,

Farre pleasanter then Nightingals in Spring.

Like to° a Ball, their Ecchoes shall rebound just like

Against the Wall, yet can no Voice be found.

Oake.

Alas, what Musick shall I care to heare,

When on my Shoulders I such burthens beare?

Both Brick, and Tiles, upon my Head are laid,

Of this Preferment° I am sore afraid. position

And many times with Nailes, and Hammers strong,

They peirce my Sides, to hang their Pictures on.

My Face is sinucht° with Smoake of Candle Lights, smudged

In danger to be burnt in Winter Nights.

No, let me here a poore Old Oake still grow;

I care not for these vaine Delights to know.

For fruitlesse Promises I do not care,

More Honour tis, my owne green Leaves to beare.

More Honour tis, to be in Natures dresse,

Then any Shape, that Men by Art expresse.

I am not like to Man, would Praises have,

And for Opinion make my selfe a Slave.

Man.

Why do you wish to live, and not to dye,

Since you no Pleasure have, but Misery?

For here you stand against the scorching Sun:

By’s° Fiery Beames, your fresh green Leaves become by its

Wither’d; with Winter’s cold you quake, and shake:

Thus in no time, or season, rest can take.

Oake.

Yet I am happier, said the Oake, then° Man; than

With my condition I contented am.

He nothing loves, but what he cannot get,

And soon doth surfet° of one dish of meat: indulge

Dislikes all Company, displeas’d alone,

Makes Griese himselfe, if Fortune gives him none.

And as his Mind is restlesse, never pleas’d;

So is his Body sick, and oft diseas’d.

His Gouts, and Paines, do make him sigh, and cry,

Yet in the midst of Paines would live, not dye.

Man.

Alas, poore Oake, thou understandst, nor can

Imagine halfe the misery of Man.

All other Creatures onely in Sense joyne[10],

But Man hath something more, which is divine.

He hath a Mind, doth to the Heavens aspire,

A Curiosity for to inquire:

A Wit that nimble is, which runs about

In every Corner, to seeke Nature out.

For She[11] doth hide her selfe, as fear’d to shew[12]

Man all her workes, least° he too powerfull grow. lest

Like to a King, his Favourite makes so great,

That at the last, he feares his Power hee’ll° get. he will

And what creates desire in Mans Breast,

A Nature is divine, which seekes the best:

And never can be satisfied, unt ill° until

He, like a God, doth in Perfection dwell.

If you, as Man, desire like Gods to bee,

I’le spare your Life, and not cut downe your Tree.

Natures Cook

DEath is the Cook of Nature; and we find

Meat drest° severall waies to please her Mind. prepared

Some Meates shee rosts with Feavers°, burning hot, fevers

And some shee boiles with Dropsies[13] in a Pot.

Some for Gelly consuming by degrees°, gradually

And some with Vlcers,° Gravie out to squeese. ulcers

Some Flesh as Sage she stuffs with Gouts, and Paines,

Others for tender Meat hangs up in Chaines.

Some in the Sea she pickles up to keep,

Others, as Brawne is sous’d[14], those in Wine steep.

Some with the Pox, chops Flesh, and Bones so small,

Of which She makes a French Fricasse withall.

Some on Gridirons of Calentures[15] is broyl’d

And some is trodden on, and so quite spoyl’d.

But those are bak’d, when smother’d they do dye,

By Hectick Feavers some Meat She doth fry.

In Sweat sometimes she stues° with savoury smell, stews

A Hodge-Podge of Diseases tasteth well.

Braines dreit° with Apoplexy to Natures wish, dressed

Or swimmes with Sauce of Megrimes° in a Dish. migraines

And Tongues she dries with Smoak from Stomacks ill,

Which as the second Course she sends up still.

Then Death cuts Throats, for Blood-puddings to make,

And puts them in the Guts, which Collicks[16] rack.

Some hunted are by Death, for Deere that’s red,

Or Stal-fed° Oxen, knocked on the Head. stall-fed

Some for Bacon by Death are Sing’d°, or scal’d°, singed

Then powdered up with Flegme, and Rhume[17] that’s salt.

Mastery Check

- To what does Cavendish compare love as a subject for poetry?

- How does Cavendish personify death?

- What is the relationship between death and nature in Cavendish’s poetry?

- What all does the man propose to build from the oak wood?

- On what grounds does the oak argue the man should spare it?

- In the end does the man cut down the oak or spare it?

- i.e., He [Death] bent all his force to hinder her [Nature]. ↵

- i.e., He [Death] does not let the Mind rest in peace. ↵

- i.e., They [Sleep and Sloth] lay her [Life] down upon their weary limbs. ↵

- "Complaint" historically means a "lamentation" or an "expression of grief" (OED). ↵

- i.e., There is no end to and no place to run from my torment. ↵

- i.e., all the while. ↵

- i.e., I [the Oak] will be mined into chips. ↵

- i.e., I'll cut you down. ↵

- The meaning here is unclear. In their edition, Paper Bodies: A Margaret Cavendish Reader (Routledge, 2000), Sylvia Bowerbank and Sara Mendelson propose that this is a printer's error for "pox," meaning a lesion. ↵

- The Man argues that all other living things only share one thing in common with humanity: sense, or the ability to perceive stimuli. ↵

- i.e., Nature. ↵

- i.e., as if afraid to show. ↵

- Dropsy refers to a disease that involves swelling, perhaps edema. ↵

- i.e., Others are soused (steeped) just like brawn (roasted tenderloin). ↵

- i.e., heat stroke. ↵

- Colic is an intestinal disease. ↵

- Phlegm and rheum. ↵