Monastics and their Books

Most preconquest British literature was produced and consumed in monasteries and abbeys, communities of Christians dedicated to the service of God. The following video lecture gives a short introduction to this important culture:

Books and their Makers

By Nicholas Hoffman

The Codex

The development of the medieval codex was a cultural watershed. As moderns, we may take for granted the intense labor and ingenuity that goes into writing a book by hand.

To participate in the Abrahimic religions (medieval or modern), you need books. For the medieval Christians of England, books provided access to the Bible, written prayers, devotional music, the liturgy, and other rituals.

Book culture in the Middle Ages wasn’t strictly about religious observance, either; treatises on medicine, the natural world, mathematics, astronomy, and other noticeably “secular” literature can be found alongside the religious texts we tend to associate with the medieval past. Diverse texts are often found alongside one another in medieval codices, and it can be increasingly difficult to draw a line with any degree of certainty between what is “religious” or “secular” at all.

We can think of the medieval book as a piece of technology—an “open source” system, where scribes, often anonymously, collected materials, re-organized them, and annotated them for future readers.[1] Regrettably, of this vast archive of medieval information, much has been lost. It’s humbling to remember that many of the most celebrated texts from the early Middle Ages, like Beowulf, only survive in one copy!

How to Make a Medieval Book

Medieval books were written, compiled, and bound on parchment—animal skins that have been cleaned, scraped, stretched, dried, and finally cut into sheets. Vellum was especially popular (a type of parchment made from calf). It’s strange to think of medieval books as animal products, but we are dealing with a time when writing a text required a serious consideration of resources. Think of it this way: one sheet of parchment from a sizeable animal could be folded twice, making just four double-sided pages (just eight pages in total). The process of making a complete codex could be understandably lengthy.

Here are some of the steps our pre-conquest scribes had to consider:

-

Once you’ve got some good parchment (here’s a video of the process, for the morbidly curious), cut and fold it to uniform size. You will be left with a collection of small booklets to be stitched together later.

-

After folding your parchment, you have to get it organized. Remember, vellum didn’t come with pre-made lines! A scribe could draw the lines in (including frames for illustrations) or poke tiny holes in the surface to act as a guide (a process called “pricking”). Watch this video on the structure of a medieval manuscript for a run-down of the process.

-

Now it’s time to add the text and decoration. Books often had more than one scribe working in tandem with illustrators. The script, or handwriting style, of a manuscript (or even a particular scribe) can tell us quite a bit about the book’s origins and dating. For example, scholars have traced the handwriting of one scribe with a tremor across numerous manuscripts. Meanwhile, decoration could take many forms, including color illustrations, gold leaf, and illuminated initials.

-

There was no delete button (but you could scrape ink away with a sharp blade). Either way, it’s a good idea to correct your manuscript (maybe…). Scribes also provided gloss (marginal or interlinear notes/translations) to make the book user-friendly. Where do you think we got the term “glossary”?

-

Finally the separate booklets are ready to be sewn together and given a protective (or sometimes ostentatiously decorative) cover.

Unraveling the Riddle of the Book

Below you will find an Old English riddle! Considering what you’ve learned about medieval codices and devotional books. Some questions to guide your reading include

- How many specific references to the book-making process can you find?

- Why do you think the poet personifies the book?

- What kind of book is this?

The Riddle of the Book

Trans. Paul Franklin Baum [link]

An enemy came and took away my life

and my strength also in the world; then wetted me,

dipped me in water; then took me thence;

placed me in the sun, where I lost all my hair.

The knife’s edge cut me— its impurities ground away;

fingers folded me. And the bird’s delight

with swift drops made frequent traces

over the brown surface; swallowed the tree-dye

with a measure of liquid; traveling across me,

left a dark track. A good man covered me

with protecting boards, which stretched skin over me;

adorned me with gold. Then the work of smiths

decorated me with strands of woven wire.

Now may the ornaments and the red dye

and the precious possessions everywhere honor

the Guardian of peoples. It were otherwise folly.

If the sons of men wish to enjoy me,

they will be the safer and surer of victory

and the stronger of heart and the happier of mind

and the wiser of spirit. They will have more friends,

dearer and closer, truer and better,

nobler and more devoted, who will increase

their honor and wealth, with love and favors

and kindnesses surround them, and clasp them close

with loving embraces. Ask me my name.

I am a help to mortals. My name is a glory

and salvation to heroes, and myself am holy.

And here it is in the original Old English. . .

Below is the text of the same riddle in the original Old English. I’ve prepared an audio recording with a short discussion of the riddle, its language, and why it looks so strange to us today.

Mec feonda sum feore besnyþede

woruldstrenga binō wætte siþþan

dyfde on wætre dyde eft þonan

sette on sunnan þær ic swiþe beleas

herum þam þe ic hæfde heard mec siþþan

snað seaxses ecge sindrum begrunden

fingras feoldan ⁊ mec fugles wyn

geond sped dropum spyrede geneahhe

ofer brunne brerd beamtelge swealg

streames dæle stop eft on mec

siþade sweartlast mec siþþan wrah

hæleð hleobordum hyþe beþenede

gierede mec mid golde forþon me gliwedon

wrætlic weorc smiþa wire bifongen ·

nu þa gereno ond se reada telg

⁊ þa wuldorgesteald wide mære

dryhtfolca helm nales dol wite ·

gif min bearn wera brucan willað

hy beoð þy gesundran ⁊ þy sigefæstran

heortum þy hwætran ⁊ þy hygebilþran

ferþe þy frodran; habbaþ freonda þy ma

swæsra ⁊ gesibbra soþra ⁊ godra

tilra ⁊ getreowra þa hyra tyr ⁊ ead

estum ycað, ⁊ hy ār stafum

lissum bilecgað ⁊ hi lufan fæþmum

fæste clyppað · frige hwæt ic hatt

niþum to nytte; nama min is mære ·

hæleþum gifre ⁊ halig sylf

The Lindisfarne Gospels

Now that you’ve analyzed an Old English riddle about a gospel book–that book that will make its readers “safer and surer of victory, “stronger of heart” and “happier of mind”–it’s time to turn to the “real thing”: one of the most spectacular books ever made. It was produced at Lindisfarne Abbey, located on the Isle of Lindisfarne off the northeastern coast of England, and created in honor of Saint Cuthbert, who died in 687.

Cuthbert, the honoree of the Lindisfarne Gospels, was one of several famous “alumni” of Lindisfarne. Narratives about his life emphasized his penchant for solitary contemplation and a closeness with animals. The coastal, monastic retreat of Lindisfarne seems the ideal place for a person like Cuthbert to cultivate his spiritual life, surrounded by coastal birds, wildlife, and a striking landscape.

From a geographical standpoint, Lindisfarne is fascinating. As mentioned above, the Holy Island is only accessible at ebb-tide, when the causeway is clear of water. The remoteness of the island made it a space of spiritual significance, fostering an isolated, contemplative space for the monastics that called it home. Its coastal isolation also made it a tantalizing target for Viking raiders.

An interesting, eco-critical aside: eider ducks would have been a common sight for the denizens of Lindisfarne Abbey. In fact, you’ll find them tucked into the elaborate designs of the Lindisfarne Gospels! These ducks are known as “Cuddy ducks” after Cuthbert, who, according to legend, protected the birds from thieves looking to steal their eggs. In one video a modern conservationist explains why he considers Cuthbert the “Father of conservation.”

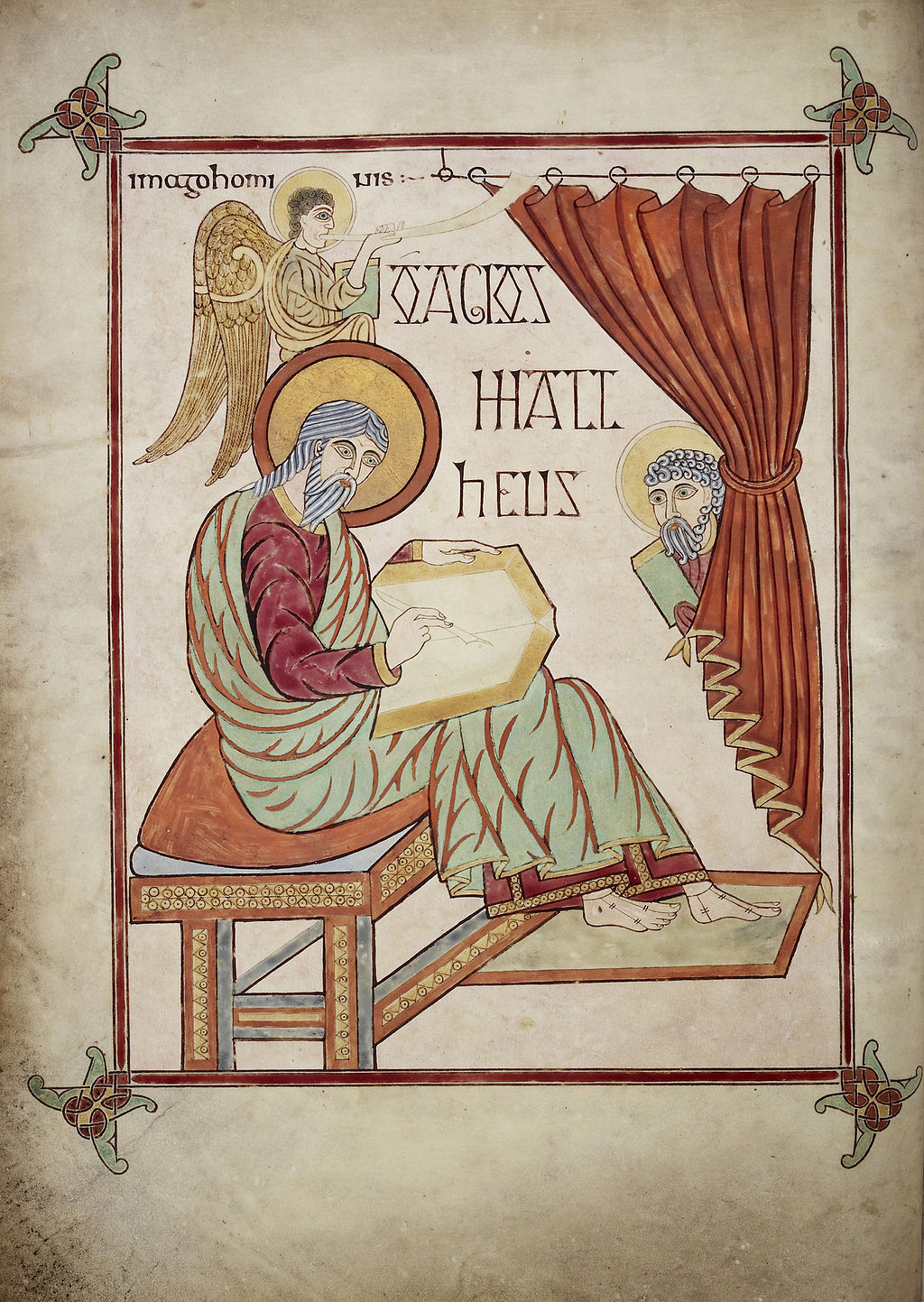

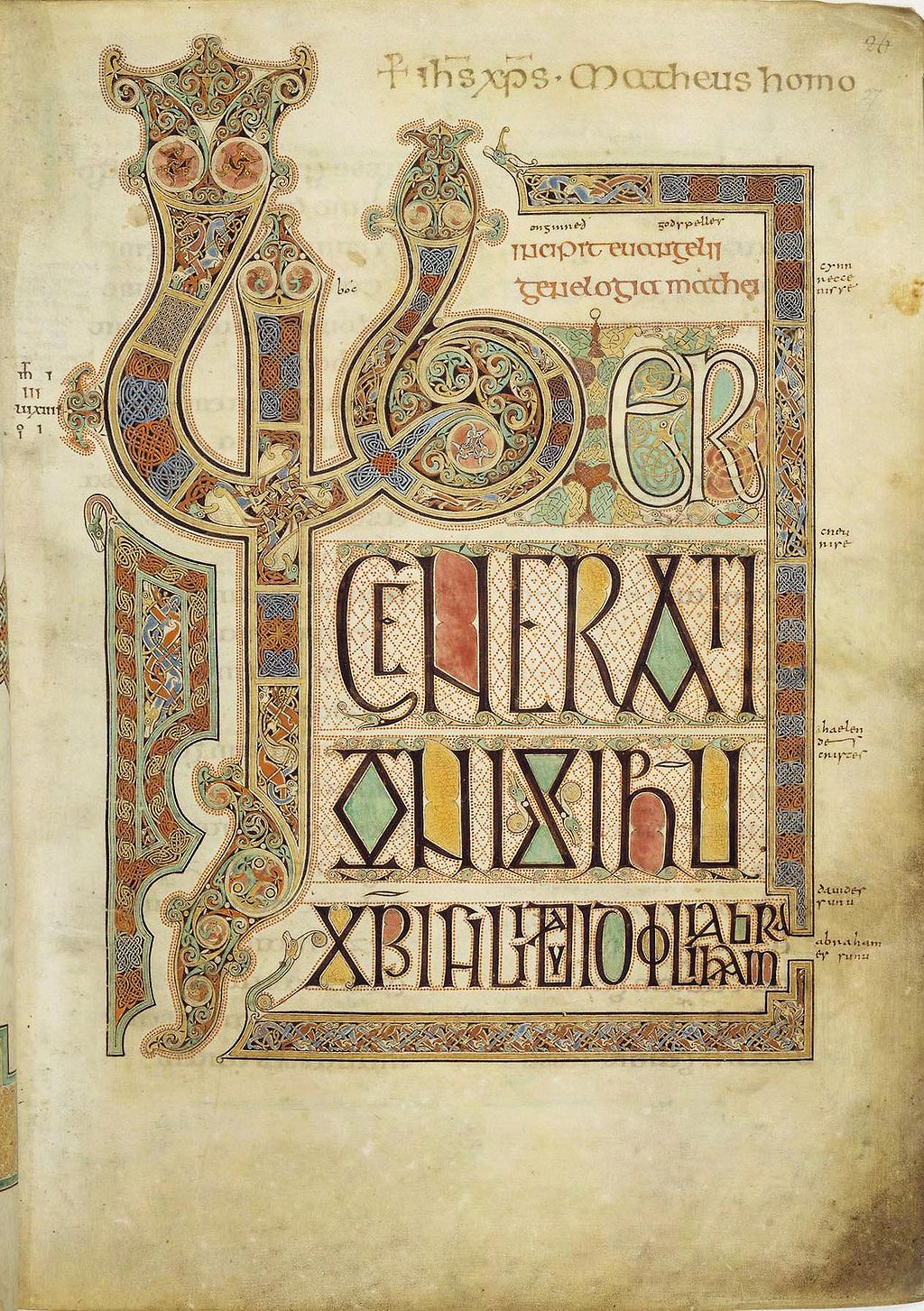

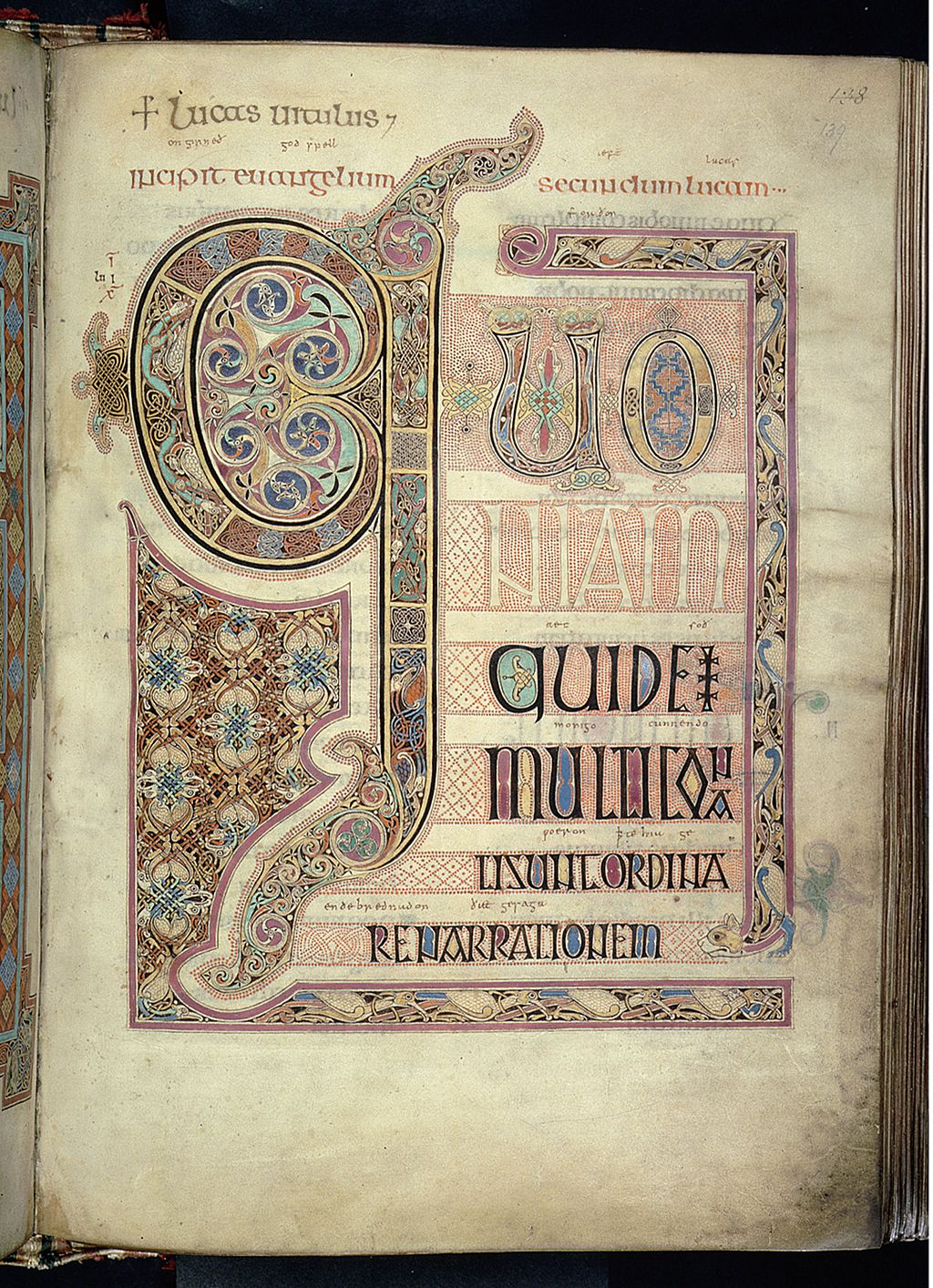

Flipping through the Gospels

Below you will find some example pages from the Lindisfarne Gospels. Take a moment to appreciate their artistry and organization. What hidden elements can you find in the manuscript’s pages?

The Book of Kells

Another elaborate Gospel book is the Book of Kells, dating from circa 800. The artists of this Book shared Eadfrith’s genius and his quirky sense of humor. Below is the famous “chi rho” page in the manuscript, so called because it consists of two decorated Greek letters, chi and rho, the first letters of the word Christ. Can you spot the human faces in the decoration? How about some mice playing tug-of-war with a communion wafer under the auspices of a pair of cats? Mischievous critters playing within the letters spelling out Christ? Mice nibbling a communion wafer, considered to be the body of Christ? This page’s blending of the sacred with what many people today consider profane can be found in much medieval religious art.

If the artists of the Book of Kells were alive today, I suspect they would be making animated movies, which require the same flights of fancy. The Book of Kells, indeed, inspired a delightful animated movie, The Secret of Kells (2009), which imagines how the Book of Kells might have come to be produced. The movie concludes by “translating” the medieval manuscript into a dazzling animated sequence.

Mastery Check:

- What language was the lingua franca spoken and written across Western Europe.

- Where was most early medieval literature produced and consumed?

- How (roughly) were books made, and what were they made of?

- Which Lindisfarne monk was renowned not only as a saint but as an early conservationist?

- How many birds has the Lindisfarne cat devoured?

- What do the rats in the Book of Kells nibble?

- What did Abbess Leoba, professor extraordinaire, insist was essential to effective study?

- For a fascinating discussion of the medieval manuscript in relation to contemporary digital culture, check out Kathleen Kennedy’s book, Medieval Hackers (punctum, 2015). ↵

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which may be a chapel, church, or temple, and may also serve as an oratory, or in the case of communities anything from a single building housing only one senior and two or three junior monks or nuns, to vast complexes and estates housing tens or hundreds. A monastery complex typically comprises a number of buildings which include a church, dormitory, cloister, refectory, library, balneary and infirmary. Depending on the location, the monastic order and the occupation of its inhabitants, the complex may also include a wide range of buildings that facilitate self-sufficiency and service to the community. These may include a hospice, a school, and a range of agricultural and manufacturing buildings such as a barn, a forge, or a brewery. (source: Wikipedia)

An abbey is a complex of buildings, a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. It provides a place for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns. (source: Wikipedia)

A codex (plural codices), is a book constructed of a number of sheets of paper, vellum, papyrus, or similar materials. The term is now usually only used to describe manuscript books, with hand-written contents, but describes the format that is now near-universal for printed books in the Western world. (source: Wikipedia)

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves, and goats. It has been used as a writing medium for over two millennia. Vellum is a finer quality parchment made from the skins of young animals such as lambs and young calves. (source: Wikipedia)

A gloss is a brief notation, especially a marginal one or an interlinear one, of the meaning of a word or wording in a text. It may be in the language of the text, or in the reader's language if that is different. (source: Wikipedia)

Cuthbert (c. 634 – 20 March 687) was an Anglo-Saxon saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in what might loosely be termed the Kingdom of Northumbria, in North East England and the South East of Scotland. After his death he became the most important medieval saint of Northern England, with a cult centred on his tomb at Durham Cathedral. Cuthbert is regarded as the patron saint of Northumbria. (source: Wikipedia)