A Personal Elegy

As you begin your exploration of “Elegy B,” please watch the following (for the lyrics, click here):

Pete Serger’s popular song, a simple but powerful indictment of war, captures the spirit of much Old English elegiac poetry:

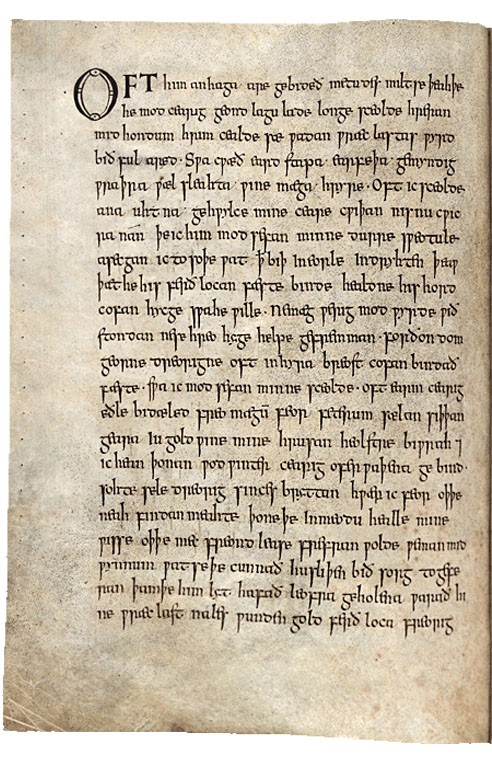

Here is the opening of Elegy B as it appears in the Exeter Book. Like Elegy A (“The Ruin”), it has no title. As you read the poem, consider what you might entitle it if you had the choice. At the end, we’ll reveal the title it was given by scholars of Old English.

Elegy B

Translated by Dr. Aaron K. Hostetter

Audio Recording 1 of 2

OFTEN the lone-dweller awaits his own favor,

the Measurer’s mercy, though he must,

mind-caring, throughout the ocean’s way

stir the rime-chilled sea with his hands

for a long while, tread the tracks of exile—

the way of the world is ever an open book. (1-5)

So spoke the earth-stepper, mindful of miseries,

slaughter of the wrathful, crumbling of kinsmen: (6-7)

Often alone, every daybreak, I must

bewail my cares. There is now no one living

to whom I dare articulate my mind’s grasp.

I know as truth that it is a noble custom

for a man to enchain his spirit’s close,

to hold his hoarded coffer, think what he will. (8-14)

Nor can the weary mind withstand these outcomes,

nor can a troubled heart effect itself help.

Therefore those eager for glory will often

secure a sorrowing mind in their breast-coffer —

just as I must fasten in fetters my heart’s ken,

often wretched, deprived of my homeland,

far from freeborn kindred, since years ago

I gathered my gold-friend in earthen gloom,[1]

and went forth from there abjected,

winter-anxious over the binding of waves,

hall-wretched, seeking a dispenser of treasure,

where I, far or near, could find him who

in the mead-hall might know of my kind,

or who wishes to comfort a friendless me,

accustomed as he is to joys. (15-29a)

The experienced one knows how cruel

sorrow is as companion,

he who has few adored protectors—

the paths of the exile claim him,

not wound gold at all—

a frozen spirit-lock, not at all the fruits of the earth.

He remembers hall-retainers and treasure-taking,

how his gold-friend accustomed him

in his youth to feasting. Joy is all departed! (29b-36)

Therefore he knows who must long forgo

the counsels of beloved lord,

when sleep and sorrow both together

constrain the miserable loner so often.

It seems to him in his mind that he embraces

and kisses his lord, and lays both hands and head

on his knee, just as he sometimes

in the days of yore delighted in the gift-throne. long ago

Then he soon wakes up, a friendless man,

seeing before him the fallow waves,

the sea-birds bathing, fanning their feathers,

ice and snow falling down, mixed with hail. (37-48)

Then the hurt of the heart will be heavier,

painful after the beloved. Sorrow will be renewed.

Whenever the memory of kin pervades his mind,

he greets them joyfully, eagerly looking them up and down,

the companions of men—

they always swim away.

The spirits of seabirds do not bring many

familiar voices there. Cares will be renewed

for him who must very frequently send

his weary soul over the binding of the waves. (49-57)

Therefore I cannot wonder across this world

why my mind does not muster in the murk

when I ponder pervading all the lives of men,

how they suddenly abandoned their halls,

the proud young thanes. So this entire middle-earth

tumbles and falls every day — (58-63)

Audio recording 2 of 2

Therefore a man cannot become wise,

before he has earned his share of winters in this world.

A wise man ought to be patient,

nor too hot-hearted, nor too hasty of speech,

nor too weak a warrior, nor too foolhardy,

nor too fearful nor too fey, nor too coin-grasping,

nor ever too bold for boasting, before he knows readily. (64-9)

A stout-hearted warrior ought to wait,

when he makes a boast, until he readily knows

where the thoughts of his heart will veer.

A wise man ought to perceive how ghostly it will be

when all this world’s wealth stands wasted,

so now in various places throughout this middle-earth,

the walls stand, blown by the wind,

crushed by frost, the buildings snow-swept.

The wine-halls molder, their wielder lies

deprived of joys, his peerage all perished,

proud by the wall. War destroyed some,

ferried along the forth-way, some a bird bore away

over the high sea, another the grey wolf

separated in death, another a teary-cheeked

warrior hid in an earthen cave. (70-84)

And so the Shaper of Men has laid this middle-earth to waste

until the ancient work of giants stood empty,

devoid of the revelry of their citizens.” (85-7)

Then he wisely contemplates this wall-stead

and deeply thinks through this darkened existence,

aged in spirit, often remembering from afar

many war-slaughterings, and he speaks these words: (88-91)

Where has the horse gone? Where is the man? Where is the giver of treasure?

Where are the seats at the feast? Where are the joys of the hall?

Alas the bright goblet! Alas the mailed warrior!

Alas the pride of princes! How the space of years has passed —

it grows dark beneath the night-helm, as if it never was! (92-6)

It stands now in the track of the beloved multitude,

a wall wonderfully tall, mottled with serpents—

the force of ashen spears has seized its noblemen,

weapons greedy for slaughter, the well-known way of the world,

and the storms beat against these stony cliffs.

The tumbling snows bind up the earth,

the clash of winter, when the darkness comes.

The night-shadows grow dark, sent down from the north,

the ferocious hail-showers, in hatred of men. (97-105)

All is misery-fraught in the realm of earth,

the work of fortune changes the world under the heavens.

Here wealth is loaned. Here friends are loaned.

Here man is loaned. Here family is loaned—

And this whole foundation of the earth wastes away!” (106-10)

So spoke the wise man in his mind,

as he sat apart in secret consultation. (111)

A good man who keeps his troth

ought never manifest his miseries

too quickly from his breast,

unless he knows his balm beforehand,

an earl practicing his courage. (112-14a)

It will be well for him who seeks the favor,

the comfort from our father in heaven,

where a fortress stands for us all. (114b-5)

Mastery Check

- What do Pete Seeger’s “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” and the Old English poem known as “The Wanderer” have in common?

- What does Ubi Sunt mean and what message is it used to convey in “The Wanderer”?

- What are the circumstances of the speaker in “The Wanderer”?

- What does the speaker reveal of his past?

- What does the speaker imagine the wolf, the bird, and the tearful warrior doing?

- What does the speaker say that wise people should (and shouldn’t) do?

- What are the two morals at the end of “The Wanderer”?

- The "earth-stepper" has buried their "gold-friend," i.e. their lord. ↵