The Monastic Imagination

In the earlier readings, we’ve seen how the early medieval monastic world was interconnected and full of creative energy. During the pre-Conquest era, a rapidly expanding literary culture was developing on the British Isles, and monastic sites became centers of literary and cultural exchange. Monks and nuns, working as scribes in monasteries, generated stunning visual and textual art, perhaps most exemplified by the Lindisfarne Gospels. Books themselves—meticulously adorned or not—were valuable commodities. In them, monastics transmitted the past, recorded the present, and pushed at the boundaries of literary achievement.

Additionally, these monastics wrote not only in the lingua franca of the day, Latin, but also their own language, Old English. The importance of the development of a vernacular literature cannot be overstated; pre-Conquest chroniclers, poets, and narrative crafters have left behind a body of work that we can safely call the foundation of English literature as we know it. These early texts, though in a foreign language, offer us a window into early medieval life and the unique, imaginative possibilities of monastic living.

Below you will find several Old English poetic texts from the pre-Conquest period. These poems vary in form, theme, and content. You’ll encounter a riddle on “creation” itself, a prayer (by a shy pig farmer named Cædmon) about the beginning the world, a dream vision about an agonized Cross, and an Old Irish lyric about a scholar and cat. Keep in mind that this is just a small cross-section of a fascinating corpus of literature, ripe for study and fresh insight from a new generation of thinkers—thinkers like you! See not only what you can learn from this poetry but also what you can bring to it to make it meaningful today.

The Rood

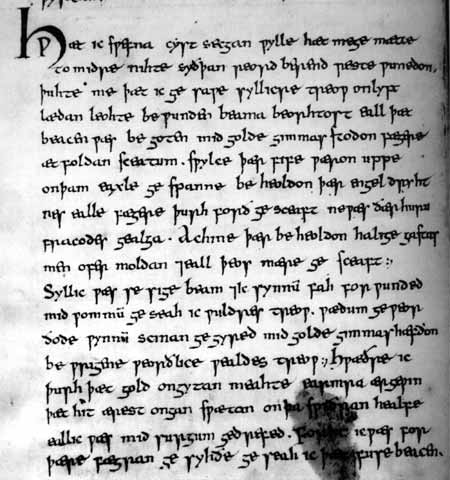

Not surprisingly, the rood, Old English rod or rode, meaning the cross upon which Christ was crucified, figured prominently in medieval art. You have seen the rood above set within one of the magnificent carpet pages of the Lindisfarne Gospels. Roods were made of stone and precious metals and paint and words. Here is one example from the tenth century:

Below you’ll find an Old English poem known today as the Dream of the Rood, which recounts Christ’s crucifixion from the perspective of the tree he was nailed to. This poem is the earliest English example of what became a hugely popular medieval genre: the dream vision, where an anxious person has a dream that somehow relates to the source of their anxieties.

This video will give you an overview of the poem and reflect upon its artistry:

The Dream of the Rood

Trans. Aaron K. Hostetler [link]

Audio 1 of 4: The Dreamer Remembers

What I wish to say of the best of dreams,

what came to me in the middle of the night

after the speech-bearers lie biding their rest! (1-3)

It seemed to me that I saw the greatest tree

brought into the sky, bewound in light,

the brightest of beams. That beacon was entirely

garnished with gold. Gemstones

prominent and proud at the corners of the earth—

five more as well blazoned across the span of its shoulders.

Every angel of the Lord warded it there,

a brilliant sight of a universe to come.

Surely it was no longer the gallows of vile crime

in that place—yet there they kept close watch,

holy spirits for all humanity across the earth,

and every part of this widely famous creation. (4-12)

Surpassing was this victory-tree, and me splattered with sins—

struck through with fault. I saw this tree of glory,

well-worthied in its dressing, shining in delights,

geared with gold. Gemstones had

nobly endowed the Sovereign’s tree.

Nevertheless I could perceive through all that gold

a wretched and ancient struggle, where it first started

to sweat blood on its right side. I was entirely perturbed with sorrows—

I was fearful for that lovely sight.

Then I saw that streaking beacon warp its hue, its hangings —

at times it was steamy with bloody wet, stained with coursing gore,

at other times it was glistening with treasure. (13-23)

Yet I, lying there for a long while,

beheld sorrow-chary the tree of the Savior

until I heard that it was speaking.

Then the best of wood said in words: (24-27)

Audio 2 of 4: The Rood Remembers

“It happened long ago—I remember it still—

I was hewn down at the holt’s end

stirred from my stock. Strong foes seized me there,

worked in me an awful spectacle, ordered me to heave up their criminals.

Those warriors bore me on their shoulders

until they set me down upon a mountain.

Enemies enough fastened me there.

I saw then the Lord of Mankind

hasten with much courage, willing to mount up upon me. (28-34)

“There I dared not go beyond the Lord’s word

to bow or burst apart—then I saw the corners of the earth

tremor—I could have felled all those foemen,

nevertheless I stood fast. (35-38)

“The young warrior stripped himself then—that was God Almighty—

strong and firm of purpose—he climbed up onto the high gallows,

magnificent in the sight of many. Then he wished to redeem mankind.

I quaked when the warrior embraced me—

yet I dared not bow to the ground, collapse

to earthly regions, but I had to stand there firm.

The rood was reared. I heaved the mighty king,

the Lord of Heaven—I dared not topple or reel. (39-45)

“They skewered me with dark nails, wounds easily seen upon me,

treacherous strokes yawning open. I dared injure none of them.

They shamed us both together. I was besplattered with blood,

sluicing out from the man’s side, after launching forth his soul. (46-49)

“Many vicious deeds have I endured on that hill—

I saw the God of Hosts racked in agony.

Darkness had covered over with clouds

the corpse of the Sovereign, shadows oppressed

the brightest splendor, black under breakers.

All of creation wept, mourning the king’s fall—

Christ was upon the cross. (50-56)

“However people came hurrying from afar

there to that noble man. I witnessed it all.

I was sorely pained with sorrows—yet I sank down

to the hands of those men, humble-minded with much courage.

They took up there Almighty God, lifting up him up

from that ponderous torment. Those war-men left me

to stand, dripping with blood—I was entirely wounded with arrows.

They laid down the limb-weary there, standing at the head of his corpse,

beholding there the Lord of Heaven, and he rested there awhile,

exhausted after those mighty tortures. (57-65a)

“Then they wrought him an earthen hall,

the warriors within sight of his killer. They carved it from the brightest stone,

setting therein the Wielder of Victories. Then they began to sing a mournful song,

miserable in the eventide, after they wished to venture forth,

weary, from the famous Prince. He rested there with a meager host. (65b-69)

“However, weeping there, we lingered a good while in that place,

after the voices of war-men had departed.

The corpse cooled, the fair hall of the spirit.

Then someone felled us both, entirely to the earth.

That was a terrifying event! Someone buried us in a deep pit.

Nevertheless, allies, thanes of the Lord, found me there

and wrapped me up in gold and in silver. (70-77)

Audio 3 of 4: The Rood’s Message:

“Now you could hear, my dear man,

that I have outlasted the deeds of the baleful,

of painful sorrows. Now the time has come

that men across the earth, broad and wide,

and all this famous creation worthy me,

praying to this beacon. On me the Child of God

suffered awhile. Therefore I triumphant

now tower under the heavens, able to heal

any one of them, those who stand in terror of me.

Long ago I was made into the hardest of torments,

most hateful to men, until I made roomy

the righteous way of life for them,

for those bearing speech. Listen—

the Lord of Glory honored me then

over all forested trees, the Warden of Heaven’s Realm!

Likewise Almighty God exalted his own mother,

Mary herself, before all humanity,

over all the kindred of women. (78-94)

“Now I bid you, my dear man,

to speak of this vision to all men

unwrap it wordfully, that it is the Tree of Glory,

that the Almighty God suffered upon

for the sake of the manifold sins of mankind,

and the ancient deeds of Adam.

Death he tasted there, yet the Lord arose

amid his mighty power, as a help to men.

Then he mounted up into heaven. Hither he will come again,

into this middle-earth, seeking mankind

on the Day of Doom, the Lord himself,

Almighty God, and his angels with him,

wishing to judge them then—he that holds the right to judge

every one of them—upon their deserts

as they have earned previously here in this life. (95-109)

“Nor can any remain unafraid there

before that word that the Wielder will speak.

He will ask before the multitude where that man may be,

who wished to taste in the Lord’s name

the bitterness of death, as he did before on the Cross.

Yet they will fear him then, and few will think

what they should begin to say unto Christ.

There will be no need to be afraid there at that moment

for those who already bear in their breast the best of signs,

yet every soul ought to seek through the Rood

the holy realm from the ways of earth—

those who intend to dwell with their Sovereign.” (110-21)

Audio 4 of 4: The Dreamer’s Hope

I prayed to that tree with a blissful heart,

great courage, where I was alone,

with a meager host. My heart’s close was

eager for the forth-way, suffering many

moments of longing. Now my hope for life

is that I am allowed to seek that victorious tree,

more often lonely than all other men,

to worthy it well. The desire to do so

is strong in my heart, and my guardian

is righteous in the Rood. I am not wealthy

with many friends on this earth,

yet they departed from here from the joys of the world,

seeking the King of Glory—now they live

in heaven with the High-Father, dwelling in magnificence,

and I hope for myself upon each and every day

for that moment when the Rood of the Lord,

that I espied here upon the earth,

shall ferry me from this loaned life

and bring me then where there is great bliss,

joys in heaven, where there are the people of the Lord,

seated at the feast, where there is everlasting happiness

and seat me where I will be allowed afterwards

to dwell in glory, brooking joys well amid the sainted.

May the Lord be my friend, who suffered before

here on earth, on the gallows-tree for the sins of man. (122-46)

He redeemed us and gave us life,

a heavenly home. Hope was renewed

with buds and with bliss for those suffered the burning.

The Son was victory-fast upon his journey,

powerful and able, when he came with his multitudes,

the army of souls, into the realm of God,

the Almighty Ruler, as a bliss for the angels

and all of the holy, those who dwelt in glory

before in heaven, when their Sovereign came back,

Almighty God, to where his homeland was. (147-56)

Mastery Check:

- What is a rood?

- What transformations take place within the poem we know as “Dream of the Rood”?

- Who are the three characters in “Dream of the Rood”

- How are they like and unlike each other?

- How are their stories interlaced?

Poems of Creation

Creation was another theme of Old English poetry. In fact, the earliest surviving poem in Old English is included in some manuscripts of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History. In one of many vivid anecdotes, Bede relays how a cowherd named Cædmon at Whitby Monastery was gifted with the ability to compose hymns of extraordinary beauty. Meanwhile, another Old English riddle, whose solution modern scholars think is either creation or the creator, offers a different take on the same theme.

Considering Creation

As you read the two poems below, reflect upon the following:

- What does “creation” encompass for these poets? What makes up the created world?

- Why do you think pre-Conquest scribes recorded these poems in Old English? What purpose could they serve in the vernacular?

- “Cædmon’s Hymn” comes from a historical text while the second poem is a riddle. How do the two poems differ in structure? Do you notice any other significant differences?

Cædmon’s Hymn

Trans. Elaine Treharne [link]

Now we ought to praise the Guardian of the heavenly kingdom,

The might of the Creator and his conception,

The work of the glorious Father, as he of each of the wonders,

Eternal Lord, established the beginning.

He first created for the sons of men

Heaven as a roof, holy Creator;

Then the middle-earth, the Guardian of mankind,

The eternal Lord, afterwards made

The earth for men, the Lord almighty.

Riddle 66 (Exeter Book)

Trans. Paull F. Baum [link]

I am greater than all this world is,

less than the handworm, brighter than the moon,

swifter than the sun. All seas and waters

are in my embraces, and the bosom of earth

and the green fields. I reach to the ground,

I descend below hell, I rise above the heavens,

the land of glory. I extend far over

the home of angels. I fill the earth,

the whole wide world and the ocean currents,

all by myself. Say what my name is.

The Scholar and the Cat

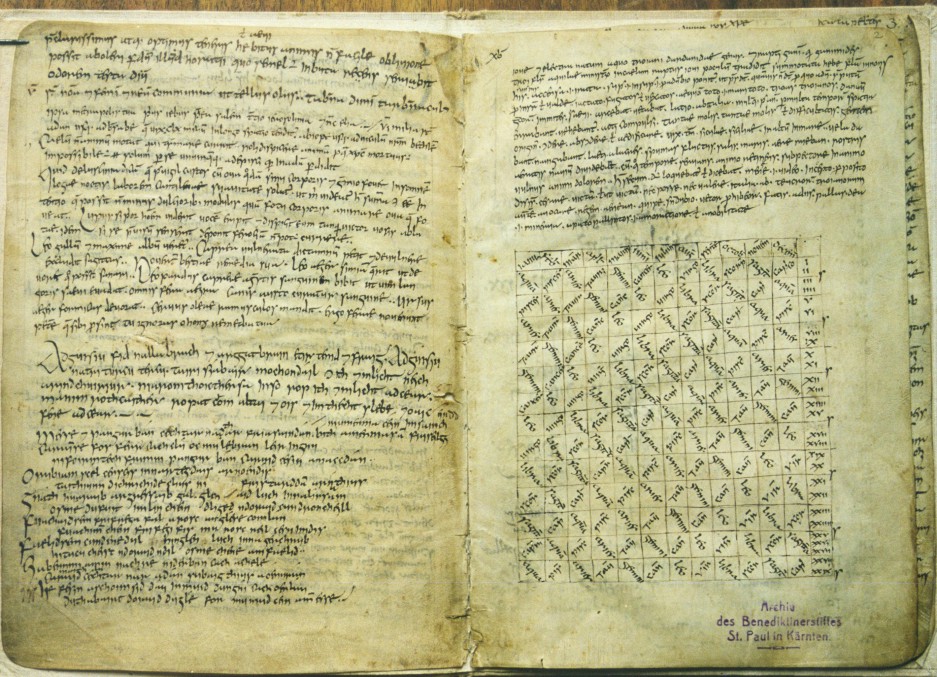

As the bird-eating cat of the Lindesfarne Gospels suggests, cats were much admired during the Middle Ages—as predators and as pets. Pictured below is the so-called Reichenau Primer, a ninth-century manuscript consisting of Latin hymns, grammar texts, astronomical tables, and (on the lower left hand of the page) a poem about a scholar and a white (bán) cat called Pangur.

If you enjoy studying in the company of your cat, you might see yourself in this poem! Check out this video to hear a reading of the poem in Old Irish by Tomás Ó Cathasaigh. Pangur Bán also appears as a character in the 2009 animated film, The Secret of Kells.

Pangur Bán

Trans. Robin Flower [link]

Old Irish Original:

Messe [ocus] Pangur bán,

cechtar nathar fria saindán;

bíth a menma-sam fri seilgg,

mu menma céin im saincheirdd

Caraim-se fós, ferr cach clú,

oc mu lebrán léir ingnu;

ní foirmtech frimm Pangur bán,

caraid cesin a maccdán.

Ó ru-biam ¬ scél cén scis ¬

innar tegdias ar n-oéndis,

táithiunn ¬ dichríchide clius ¬

ní fris ‘tarddam ar n-áthius.

Gnáth-huaraib ar greassaib gal

glenaid luch ina lín-sam;

os me, du-fuit im lín chéin

dliged ndoraid cu n-dronchéill.

Fúachaid-sem fri freaga fál

a rosc a nglése comlán;

fúachimm chéin fri fégi fis

mu rosc réil, cesu imdis.

Fáelid-sem cu n-déne dul,

hi nglen luch ina gérchrub;

hi-tucu cheist n-doraid n-dil,

os mé chene am fáelid.

Cia beimini amin nach ré

ní derban cách a chéle;

mait le cechtar nár a dán

subaigthiud a óenurán.

Hé fesin as choimsid dáu

in muid du-n-gní cach óenláu;

do thabairt doraid du glé

for mumud céin am messe.

Translation:

I and Pangur Ban my cat,

‘Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

Better far than praise of men

‘Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill-will,

He too plies his simple skill.

‘Tis a merry task to see

At our tasks how glad are we,

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind.

Oftentimes a mouse will stray

In the hero Pangur’s way;

Oftentimes my keen thought set

Takes a meaning in its net.

‘Gainst the wall he sets his eye

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

‘Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.

When a mouse darts from its den,

O how glad is Pangur then!

O what gladness do I prove

When I solve the doubts I love!

So in peace our task we ply,

Pangur Ban, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.

Mastery Check:

- How does “Pangur Ban” resemble or differ from the Old Irish poet/scholar?

Cædmon (fl. c. AD 657–684) is the earliest English poet whose name is known. A Northumbrian who cared for the animals at the double monastery of Streonæshalch (now known as Whitby Abbey) during the abbacy of St. Hilda, he was originally ignorant of "the art of song" but learned to compose one night in the course of a dream, according to the 8th-century historian Bede. He later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational Christian poet. (source: Wikipedia)

A rood or rood cross, sometimes known as a triumphal cross, is a cross or crucifix, especially the large crucifix set above the entrance to the chancel of a medieval church. Alternatively, it is a large sculpture or painting of the crucifixion of Jesus. (source: Wikipedia)

A dream vision or visio is a literary device in which a dream or vision is recounted as having revealed knowledge or a truth that is not available to the dreamer or visionary in a normal waking state. While dreams occur frequently throughout the history of literature, visionary literature as a genre began to flourish suddenly, and is especially characteristic in early medieval Europe. In both its ancient and medieval form, the dream vision is often felt to be of divine origin. The genre reemerged in the era of Romanticism, when dreams were regarded as creative gateways to imaginative possibilities beyond rational calculation. (source: Wikipedia)