Kickin’ Back in the Cloister

Monastic Leisure

Guided by Nicholas Hoffman

As scribes, chroniclers, scientists, and poets, many medieval monks and nuns actively studied and produced striking textual and visual art. But you may be wondering: how exactly did monastics pass the time?

Much time in the monastery was spent in prayer. The Canonical Hours are a set of psalms and hymns sung at specific increments of the day. In the early Church, they included (with rough time approximations): matins (2 a.m.); lauds (5 a.m.); prime (6 a.m.); terce (9 a.m.); sext (12 p.m.); none (3 p.m.); vespers (6 p.m.); and compline (7 p.m.). In between the Hours, monastics busied themselves not only with scribal work but also the daily activities necessary to keep the monastery running—cooking, cleaning, crafting, etc.

But that doesn’t mean they didn’t know how to unwind. Below you’ll find some examples of a thriving monastic leisure life. Monks and nuns played games, wrote plenty of material we’d characterize as “secular,” kept pets, drank, sang, acted, and developed their own code languages.

Also, be sure to check out one of my favorite videos: some Franciscan monks capitalizing on a snowstorm in Jerusalem to have an impromptu snowball fight.

Hnefatafl was a strategy game in which one side attempted to capture the king, while the other side attempted to ward off their attackers. To the left is a 7th-8th century Hnefatafl board found at the site of a medieval monastery in Scotland.

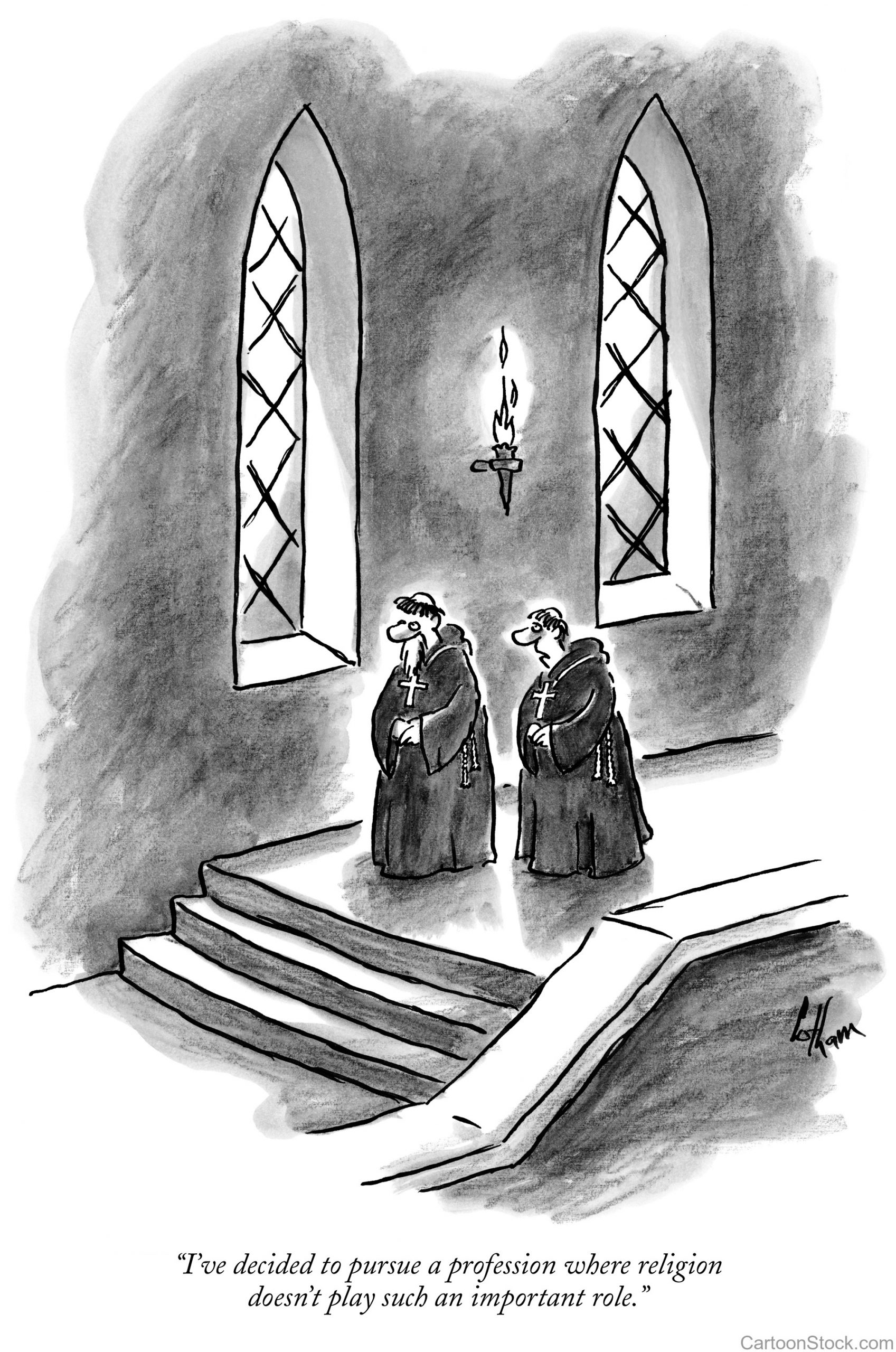

Not all of the literature produced in monasteries was serious and devout. To the right is an example of goliardic literature. Think of the Goliards as the medieval monks who were “too cool for school.” They wrote humorous Latin poetry, using their education to (sometimes viciously) satirize the Church.

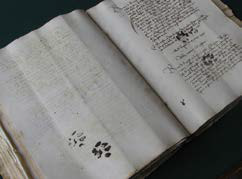

Though pets were not as common in the medieval world as they are today, it appears they were still popular among monastics. A photo taken by Emir O. Filipović, an archival researcher, took the internet by storm a while back. The photo shows the remnants of an all-too-recognizable event for cat owners: it appears our feline friend tipped over an ink well and proceeded to walk all over the manuscript.

Yes, monks and nuns were known to imbibe. Many monasteries were developed with brewing operations in mind. Not only was wine important for the Christian liturgy, but monasteries celebrated calendrical feasts throughout the religious year. Additionally, medieval monks and nuns housed and entertained guests who may have wanted a tipple.

Even vows of silence couldn’t keep monks totally quiet. Depending on the monastic order and its rules, vows of silence were periodically taken as a form of devotion. Interestingly, monks and nuns got creative, developing their own systems of sign language.

Hildegard of Bingen, a German abbess of the 12th century, was a prolific writer. She recorded a series of mystical visions (the Scivias) as well as several scientific treatises. However, one text in particular, her Ordo Virtutum is the earliest example of a Christian morality play. Hildegard’s monastic “musical” reminds us just how central drama and music were to life in the cloister.

Reading Medieval Marginalia

Scribbles. Unicorns. Genitals. You can find a lot in the margins of medieval manuscripts. These marginal drawings, called marginalia, populate many manuscripts. Sometimes they were planned as part of an ornate frame or to provide commentary on a text. Other times they seem spontaneous, even humorous—perhaps evidence of a kind of medieval “meme culture.” Something you may have seen floating around online is the medieval infatuation with giant, aggressive snails (yes, you read that correctly). Book-making was certainly a labor intensive, devotional act in the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, it was also a human act, and medieval marginalia offer us a view into the creativity and wit of some of these “austere” nuns and monks.

Riddling in Old English

The creation/creator riddle you read above is one of almost 100 riddles in Old English, most of them preserved in a tenth-century manuscript known as the Exeter Book. In the Exeter Book itself, the scribe just gives the riddles: no solutions are provided. The solutions given in riddle anthologies are modern scholars’ best guess.

Riddles hold special significance in the history of Old English literature. Riddles are culturally ubiquitous—often transmitted orally within communities and across generations. Before the Middle Ages, riddles were primarily written down in Latin. In the pre-Conquest period, monastics put quill to parchment to record some of their favorites, and their subjects show remarkable range—religious items, geographic features, weapons, vegetables, etc.

It’s difficult to really pin down what Old English riddles are. Here are a few quick considerations as you’re reading:

- Riddles could serve as teaching tools, shedding light on natural phenomena, doctrine, and daily life. Riddles were part of a sustained Latin literary tradition; like their Latin counterparts, Old English riddles may have been used to teach the rules of metrics and poetic composition.

-

We can’t forget that Old English riddles were transmitted as poems. Just like Beowulf or Dream of the Rood, they are composed in alliterative verse and make ample use of kennings.

-

Lastly, the Old English riddles may reflect a form of monastic leisure. You’ll soon discover that some of the riddles aren’t particularly “religious,” let’s say. They are frequently playful and full of tongue-in-cheek humor.

Be a Riddle Master!

Test your wits on the three riddles given on the following pages (all trans. by Paull F. Baum). Identify the hints within each riddle and make your best guess!

NOTA BENE! Modern scholars have come up with answers to most of the Old English riddles. Don’t try to look them up. The value of this exercise is in deciphering the riddles on your own. There’s no glory in coming up with the same answers the scholars came up with. Besides, the “experts” aren’t necessarily right. The Old English poets did not provide any solutions to their riddles.

Riddle 1

My garment is darkish. Bright decorations,

red and radiant, I have on my raiment.

I mislead the stupid and stimulate the foolish

toward unwise ways. Others I restrain

from profitable paths. But I know not at all

that they, maddened, robbed of their senses,

astray in their actions —that they praise to all men

my wicked ways. Woe to them then

when the Most High holds out his dearest of gifts

if they do not desist first from their folly.

Riddle 2

I’m a wonderful thing, a joy to women,

to neighbors useful. I injure no one

who lives in a village save only my slayer.

I stand up high and steep over the bed;

underneath I’m shaggy. Sometimes ventures

a young and handsome peasant’s daughter,

a maiden proud, to lay hold on me.

She seizes me, red, plunders my head,

fixes on me fast, feels straightway

what meeting me means when she thus approaches,

a curly-haired woman. Wet is that eye.

Riddle 3

I am a lonely thing, wounded with iron,

smitten by sword, sated with battle-work,

weary of blades. Often I see battle,

fierce combat. I foresee no comfort,

no help will come for me from the heat of battle,

until among men I perish utterly;

but the hammered swords will beat me and bite me,

hard-edged and sharp, the handiwork of smiths,

in towns among men. Abide I must always

the meeting of foes. Never could I find

among the leeches, where people foregather, physicians

any who with herbs would heal my wounds;

but the sores from the swords are always greater

with mortal blows day and night.

Mastery Check

- How did medieval monks and nuns unwind? Be able to name at least three forms of recreation.

- What kinds of things did they scribble in the margins of manuscripts?

In the practice of Christianity, canonical hours mark the divisions of the day in terms of periods of fixed prayer at regular intervals. A book of hours normally contains a version of, or selection from, such prayers. (source: Wikipedia)

The goliards were a group of clergy, generally young, in Europe who wrote satirical Latin poetry in the 12th and 13th centuries of the Middle Ages. They were chiefly clerics who served at or had studied at the universities of France, Germany, Spain, Italy, and England, who protested against the growing contradictions within the church through song, poetry and performance. Disaffected and not called to the religious life, they often presented such protests within a structured setting associated with carnival, such as the Feast of Fools, or church liturgy. (source: Wikipedia)

Hildegard of Bingen, also known as Saint Hildegard and the Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, visionary, and polymath. She is one of the best-known composers of sacred monophony, as well as the most-recorded in modern history. She has been considered by many in Europe to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany. (source: Wikipedia)

Marginalia (or apostils) are marks made in the margins of a book or other document. They may be scribbles, comments, glosses (annotations), critiques, doodles, or illuminations. (source: Wikipedia)

The Exeter Book, Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501, also known as the Codex Exoniensis, is a tenth-century book or codex which is an anthology of Anglo-Saxon poetry. It is one of the four major Anglo-Saxon literature codices, along with the Vercelli Book, Nowell Codex and the Cædmon manuscript or MS Junius 11. The book was donated to the library of Exeter Cathedral by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, in 1072. It is believed originally to have contained 131 leaves, of which the first 8 have been replaced with other leaves; the original first 8 pages are lost. The Exeter Book is the largest known collection of Old English literature still in existence.

In 2016, UNESCO recognized the book as one of the "world's principal cultural artifacts". (source: Wikipedia)

Alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principal ornamental device to help indicate the underlying metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme. The most commonly studied traditions of alliterative verse are those found in the oldest literature of the Germanic languages, where scholars use the term 'alliterative poetry' rather broadly to indicate a tradition which not only shares alliteration as its primary ornament but also certain metrical characteristics. The Old English epic Beowulf, as well as most other Old English poetry, the Old High German Muspilli, the Old Saxon Heliand, the Old Norse Poetic Edda, and many Middle English poems such as Piers Plowman, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and the Alliterative Morte Arthur all use alliterative verse. (source: Wikipedia)

A kenning is a figure of speech in the type of circumlocution, a compound that employs figurative language in place of a more concrete single-word noun. Kennings are strongly associated with Old Norse-Icelandic and Old English poetry. They continued to be a feature of Icelandic poetry (including rímur) for centuries, together with the closely related heiti. (source: Wikipedia)