1 Manifest Destiny: The American Dream or an Ecological Crisis?

Georgia McLachlan

My name is Georgia! My inspiration for this paper on the environmental implications of manifest destiny comes from my passions for history and environmentalism. American history has always been one of my favorite subjects, and as an environmental policy major, I felt that studying the environmental impacts of a major American historical movement would create a compelling textbook chapter…read more.

A quintessential part of the “American dream” is freedom. Whether it be freedom of religion, freedom of speech, or simply freedom to pursue one’s own dreams, Americans have always idolized the United States as a sort of utopia for individual freedom. “Manifest destiny” is a mindset that embodies this belief. A staple term in every elementary, middle, and high school student’s American history textbook, it might be considered the epitome of what it meant to be American at the start of American imperialism. The idea of manifest destiny gained popularity in the mid-19th century and was built upon the notion of freedom. Advocates for manifest destiny believed that Americans were free, even bound by fate, to conquer the North American continent and expand the realm of democratic republicanism and Christianity. Under the guise of religious, political, and economic motivations, manifest destiny allowed Americans to pursue the “American dream” and subdue the “wild west.” The environmental and humanitarian implications of manifest destiny were frequently overlooked or not considered, resulting in ideology that still today seeps into our behaviors and perceptions regarding domination and superiority.

Historical Context

One of the defining moments of American history was undoubtedly the Louisiana Purchase. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson bought 827,000 square miles of land that stretched from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and from Canada to New Orleans (history.com, 2019). In true capitalist style, he paid nowhere near what the land was worth, and his savvy business venture paid off. This land acquisition would allow the United States to continue the expansion that was such a staple asset of the country – the Louisiana Purchase almost doubled the entire land area of America. With this new land, settlers could travel westward, escaping the crowded city life and trading it for a peaceful homestead in the Great Plains. Jefferson believed a republic like the United States was built on independence and virtue, both of which could be attained and strengthened through individual land ownership. This pride in land ownership has been at the forefront of American ideology ever since. The first drafts of the Declaration of Independence included philosopher John Locke’s trinity of rights – life, liberty, and property – which suggested these were inalienable rights that an equitable, principled government could not repress from its citizens. Americans saw property ownership as an integral part of being a citizen (Dobson, 2013). Although the term “property” was replaced with the phrase “pursuit of happiness,” the sentiment still remained. People across the growing country hoped to fulfill their dream of starting a new life in the pristine land of the North American west.

In the years following the Louisiana Purchase, the U.S. government continued to acquire land through various treaties and conflicts. By the end of the Mexican American War (1848), the United Stated had expanded to reach the Pacific coast to the west and the Rio Grande River to the south (Heidler & Heidler, 2020). The allure of land ownership was a leading force in propelling settlers westward. Natural resources such as gold, silver, and timber were plentiful and tempting to many. Settlers were attracted to the empty prairies, which provided them with space to build a homestead and a farm to raise livestock and crops such as wheat and corn (Dobson, 2013). In the early 1840s, thousands of prospective landowners and their families traveled the Oregon Trail (history.com, 2019). They braved storms, food shortages, and disease, fixated on the prospect of upward social mobility, freedom, and the start of a new life (history.com, 2019). By the mid-19th century, technological advancements such as the steam engine and subsequent construction of the Transcontinental Railroad made communication and transportation of goods much more efficient and accessible for settlers and the families they left back East.

Government legislation in the mid-19th century helped streamline the process of moving westward. The Homestead Act of 1862 granted citizens of the United States the ability to claim 160 acres of government-surveyed land. As long as these settlers remained on the land for five years, they could apply to receive the deed of title to become the official owner of the land (National Archives, 2019). Prior to this legislation, land distribution was arbitrary and not centralized; people’s claims often overlapped and there were frequent border disputes among settlers (National Archives, 2019). The Homestead Act made westward expansion much more accessible to people looking to start a new life.

Manifest Destiny

The term “manifest destiny” was first used by journalist John O’Sullivan in an 1845 essay voicing his opinion on the need for American expansion (Heidler & Heidler, 2020). He wrote that European powers must refrain from interfering in what he referred to as America’s right to the “fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent” (Wilsey, 2017, p. 3). When he further elaborated on the term a few months later, the idea gained popularity and became a nationalistic rallying cry (Heidler & Heidler, 2020). O’Sullivan’s use of the term was a way to justify the spread of democratic republicanism, suggesting it was fate for Americans to conquer the continent. The actual phrase “manifest destiny” was simply a name for a common sentiment that had been felt among Americans for decades (Heidler & Heidler, 2020). There was a fascination with the untamed, uncharted lands that lay to the west.

The term “manifest destiny” invokes a certain religious association. The word “destiny” suggests that God or some other higher being has predetermined the fate of humans and has given preferential treatment to Americans and their desire for westward expansion. It seemed obvious that the only way such small, insignificant colonies could have risen to become a world power in such a short time was through the will of God. It made sense, and it was easy to justify. The idea had been present since the beginning of European settlements in the Americas in the early 17th century. John Winthrop, one of the Puritan founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, wrote that his settlement in New England was “a city on a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us” (Dobson, 2013, p. 42). He and his fellow settlers believed that their colonies had been chosen by God to be a pristine example of society. This ideology continued to be present as more settlements arose along the Eastern seaboard.

Religion became even more tied to dominionistic settlement in later years. O’Sullivan, the journalist credited with creating the phrase “manifest destiny,” was a believer in the dominion mandate from God. The Creation story reads, “God blessed them and said to them…fill the Earth and subdue it. Rule over…every living creature” (Genesis 1:28, New International Version). Other Christian settlers likened themselves to the Israelites from the book of Exodus. They believed that they were being led by God to a new promised land – the west – just as He had led the Israelites out of Egypt (Dobson, 2013). William Gilpin, a strong proponent of westward railroad expansion, published a book titled The Central Gold Region, which made the argument that the Mississippi River Valley was destined to be the center of world trade. His justification for this belief was religiously motivated. Gilpin states, “The destiny of the American people is to subdue the continent…to change darkness into light and confirm the destiny of the human race” (PBS, 2001). He also remarks that the Mississippi River Valley “…is the most magnificent dwelling-place marked out by God for man’s abode” (Gilpin, 1860, p. 184). Using the dominion mandate, Christianity was becoming wrapped up as an excuse for destructive economic endeavors.

In reality, Christian religion (or any religion) does not condone this sort of dominionistic, condescending attitude toward the natural environment. This way of thinking cannot be considered a “Christian” perspective; it is motivated by entirely other reasons. As Theodore Hiebert (1996) explains, isolating this one verse of Genesis ignores the rest of the Creation story – that God has entrusted humans to take care of the earth and its living creatures. “Dominion” in this sense is God giving humans a responsibility to act justly and righteously, not to destroy what He has created. Humans are at the top of the hierarchy in terms of intelligence and morality, so we are given the task of exercising stewardship of the earth through God’s instruction (Hiebert, 1996). The actions of individual settlers – cutting down trees, relying on railroad development, countless growing settlements – culminated in a dominion- and development-inspired movement that resulted in far more significant consequences than anyone likely envisioned. However, the notion of taking unrestrained control of the land (especially taking it out of the control of indigenous people who had lived there for centuries) contradicts the whole premise of stewardship that is an essential tenet of Christianity and many other world religions.

The association between Christianity and manifest destiny was largely upheld by a pseudo-religious agenda. Operating under the guise of religion made people’s actions appear more credible and acceptable. Reinhold Niebuhr (1939) explains that humans suffer from a moral dilemma – we have the free will to do whatever we like, but we are finite and are ultimately going to die. This leads to insecurity and anxiety, and if we fail to trust in God, we will commit a sin of self-assertion, what Niebuhr calls the sin of pride. This self-assertion might manifest itself as religious pride, which Niebuhr describes as claiming divine sanction and believing your religion makes you superior. The sin of religious pride helps, to some extent, to encapsulate the phenomenon of manifest destiny. [1] There was a societal call to spread Christianity and democracy to the rest of the continent, which was validated by the notion that God had granted His chosen people with this task. This religious sanction, in turn, meant that indigenous tribes lost their land and other countries vying for part of the continent had no foothold. But religious pride tells only part of the story.

The desire for domination, both of land and of people, lies in an innate need for control. According to Richard Baer (1976), people in western society have a need for control – exerting dominance over things less powerful allows people to shape their environment and increase their wealth and status. European settlement of North America was no different. Even from the very beginning of colonization in the Americas, politics and power were involved. Joint-stock companies established some of the first British settlements in North America, which helped investors gain control of natural resources and economic power in the New World. After the United States separated from England, it needed a way to prove itself as a world power. The idea of manifest destiny provided a solution. If it was America’s God-given right to take control of the continent, then European powers would be defying God’s word by trying to compete with them. With no competition, Americans would have access to a plethora of natural resources and land for expansion.

The desire for control and the internalized sin of religious pride might help to explain why manifest destiny was so powerful and widespread, but the average American pioneer had little power. Life on a homestead or in a Conestoga wagon was unforgiving and harsh, and before the spread of the railroad, it was difficult to efficiently get supplies out west. These individual settlers weren’t exactly the embodiment of the powerful American nation. They were just trying to make a better life for themselves. They didn’t really have power to exert over anything, and it must have hardly felt like God’s divine mandate to live in such hostile conditions. [2] Settlers were at the mercy of the elements, but they had the backing of the country behind them.

Environmental and Humanitarian Implications

The tragedy of westward expansion was the unintended consequences of destruction and loss of life. Although it was not the fault of any individual settler, it was the culmination and scale of everyone’s actions that led to severe implications for both the natural environment and the indigenous population that already lived on the continent. The construction of homesteads, towns, and railroads caused habitat segmentation – the division of one complete habitat into smaller, disjunct pieces. This alteration of the natural environment meant that wildlife was ousted, and ecosystems were degraded. Forest cover had been reduced from about 1.05 billion acres in 1630 to about 758 million acres by 1907, a 27% reduction (US Forest Service, 2001). The American bison, a species which had once dominated the plains, had to compete with livestock for food (Dobson, 2013). Previously numbering at least 30 million in the 1500s, bison were killed in alarmingly high numbers, leaving only an estimated 325 wild bison remaining in the United States by 1884 (USFWS, n.d.). Mass hunting of bison was problematic for the native population, who valued the bison for food, clothing, shelter, and its ceremonial uses (Dobson, 2013). The reduction of such a plentiful, large species throughout the Great Plains significantly altered the natural environment.

On the surface, it seems as though the blame might be placed on the pioneers. They arrived, and suddenly the land was destroyed, and animals died in mass. But these settlers were faced with conditions they had no control over. They, too, were just trying to survive in an unfamiliar environment without access to many of the resources and supplies they had had back East. Pioneers were pitted against nature as their enemy, so they did everything in their power to defeat it – it was a choice between letting nature beat them or making sure nature was beaten. Native tribes had lived on the land for centuries, but the scale of their inhabitance was so insignificant that any damage they caused to the land was not severe or permanent. Their mobility allowed them to move when resources became scarce, which gave the land time to recover from any harm they caused it (Cronon, 1983). American settlers, in contrast, had a completely different approach to land. Land ownership was a central part of life for them; indigenous tribes, on the other hand, did not recognize land ownership as a right, or even as a way of organizing society. They associated land with spirituality and sacredness, and they held a belief in a land ethic that promoted existing in harmony with the natural environment. This clash in ideology proved difficult to remedy.

Native Americans felt the collateral damage of westward expansion as well. Following the United States’ acquisition of western land, natives were forcibly removed in order for white settlers to claim their land. President Andrew Jackson initiated a removal policy in the 1830s that came to be known as the Trail of Tears, which had horrific consequences and caused some question as to the legitimacy of the westward campaign (Heidler & Heidler, 2020). Treaties to bring land under the jurisdiction of the U.S. government were often forced upon Native American tribes, effectively removing them from their own land and hunting grounds (Dobson, 2013). This abhorrent mistreatment of the people who had occupied the land for centuries was a consequence of the American ambition for domination. [3]

Taking Inspiration, Not Resources

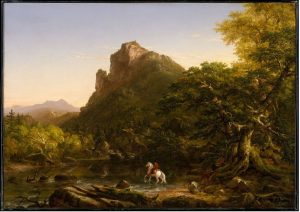

The appeal of the natural environment manifested itself in far more ways than harmful physical domination. A countertrend to the decimation that took place in the west, transcendentalist artists and writers sought to capture the sense of intrigue and adventure that initially prompted settlement of the west. The theme of manifest destiny is present in the 19th century Hudson River School art movement. Artists such as Thomas Cole, Albert Bierstadt, and Frederic Edwin Church encapsulated the divine beauty of the American landscape in their artwork (Britannica, n.d.). Their paintings invoke a sense of pride, wonder, and an appreciation of nature’s magnitude through depictions of the phenomenal expanse of wilderness. The first wave of the movement focused on New York’s Hudson River Valley, but the second wave spread out west to capture everything from the Grand Canyon, to the Mississippi River, to the Rocky Mountains. Many of these works have an underlying theme suggestive of a divine presence. The way they capture bright light shining from the heavens or simultaneously portray a stunning yet equally threatening sky above a powerful panorama of the valley below is a subtle suggestion that a higher being must be responsible for such beauty. Thomas Cole, one of the early leaders of the movement, was captivated by the wildness of American scenery. He once remarked that “we are still in Eden,” referencing Genesis and the Creation story and suggesting that the natural world of North America still contained the untouched beauty of the Garden of Eden (Ellis, 2019, p. 21). In addition to his Christian beliefs, he expressed an attraction to pantheism, which pairs the beauty of nature with divinity itself (Ellis, 2019). Cole’s work inspired artists for decades to create this type of spirituality-invoking wilderness art.

As with other aspects of this topic, this artistic appreciation of the West was more complex than a simple wish to portray God’s creation. On the surface, romantic paintings cast light on people’s captivation by beauty and the unknown. The average person was not able to travel out west to reach such remote locations as today’s national parks, so artists were able to capture the country’s beauty and bring it back East. Instead of focusing on the negative aspects of expansion, the Hudson River School artists were able to capture some of the more profound, intimate emotions evoked by taking in a beautiful panorama of the Rocky Mountains, Yosemite Valley, or a towering forest. These locations were characterized as wild and untamed, and, in reality, people knew very little of what was actually out there. [4]Often, the human figures in these paintings were subtle or even not present at all, which reminds the painting’s viewer of nature’s grandeur and intangible power. The focus on the force of nature strengthens the idea that God is more powerful than any human, no matter how much one might attempt to exert one’s strength. This transcendentalist art movement allows us still today to step back from our presence in nature and feel a sense of divine connection to the beauty of the natural world.

Of course, much of the motivation behind this second wave of Hudson River School artists traveling out west was spurred by a desire to expand and promote the development of the railroad. Depicting the American west as untouched, full of untamed, limitless resources helped to develop a sense of pride in the country and how far it had come from its humble roots (Seiferle, 2021). In some ways, the Hudson River movement helped invigorate the preservation movement and show people how important it was to protect the beautiful environment that was implicitly divine, but in other ways it simply propagated American expansionism and the profit-driven desire to “tame” the west.

Manifest Destiny and the Present Day

The roots of manifest destiny ideology are still present in American society today. It seems as though people constantly want to have a new frontier or some sort of uncharted territory that they can look toward with wonder, curiosity, and even domination. Now, one embodiment of manifest destiny turns inward – to the lure and appeal of the suburbs. The recent spread of growth from towering cities to low-density housing developments on the outskirts of the metropolis stems from the same factors as what spurred the westward expansion of the 19th century (Schmidt, 2004). People who live in the big city often aspire to move to the suburbs to start a family, buy a house with a backyard, and own a car or two. Moving to the suburbs also suggests one might be more closely connected to nature (Schmidt, 2004). After all, streets in the suburbs are lined with trees, kids play outside, and there is less pollution. Similar reasoning led thousands to migrate west. They wanted to live in a place that was not overrun by factories, smog, and people. While it sounds ideal on paper, suburban sprawl has contributed to habitat fragmentation and a decline in biodiversity, as did 19th century westward expansion (Schmidt, 2004).

The roots of manifest destiny ideology are present in other aspects of our daily lives. The American economy relies on constant consumption – everything from clothes to cell phones to furniture is made with planned or perceived obsolescence in mind. Consumption gives consumers power to influence their personal image and buy products that they hope will improve their happiness and well-being. Though conspicuous consumption might not encapsulate the sins of pride or power that were so evident in the manifest destiny movement of the 19th century, another sin of self-assertion might be at play: a sin of idolatry. People have become so wrapped up in maintaining an impeccable self-image that they neglect the fact that their consumption comes at a severe price for the environment – mass production of goods requires mass use of natural resources, many of which are non-renewable. Instead of focusing on aspects of our lives that bring us closer to finding selfless sources of happiness and security, people have become so heavily reliant on buying more “stuff” to feel fulfilled – the “stuff” has become an idol of sorts. Similar to the settlers of the 19th century, we have our own best interests in mind when we consume products to such a large extent. But what we do not always consider is how our individual actions affect the bigger picture. Although I might consider my purchase of a cheaply made t-shirt to be a win for my bank account and my wardrobe, the culmination and scale of everyone’s similar purchasing habits puts a heavy strain on the natural environment.

Final Thoughts

Manifest destiny is an ideology that encapsulates the root of many Americans’ ideals. It combines religion, freedom, and a patriotic duty to spread democratic republicanism. The way it manifested itself, in destruction and domination, is not a characteristic of traditional religious morals, though, so assigning Christianity as the reason for seeking dominion over the “wild west” is incoherent. The dominionistic, self-centered mindset of many manifest destiny-motivated settlers in the 19th century was more a result of aspiration for economic gain and an inherent bias toward their own ideals than a reflection of any religiously motivated morals. Those who truly believed in a religious obligation to dominate the continent were afflicted by religious pride and an innate desire for control, and this attitude permeated the overall dynamic of westward expansion. Christianity was largely a veil used to justify the actions propagated by the national government of a young country aspiring for world power. In contrast, the true values of Christianity would suggest we should let go of this “pride of domination”. This pseudo-Christian, dominionistic mindset became ingrained in American culture, though, and has had severe environmental and humanitarian implications for indigenous tribes, ecosystems, and wildlife. Today, this power-driven mindset is felt in a societal shift to the suburban lifestyle and mass consumer culture.

These complex dynamics may leave us wondering, how can we eliminate the harmful mindsets and ideological roots that have led us to this point? Sins of pride, power, and idolatry do not tell the whole story – there are counter trends and alternative visions that were (and still are) mixed in with the dominant exploitative and consumeristic mindsets. Instead of drawing upon nature solely as a tool for our own betterment, we can follow the inspiration of the Hudson River School artists and seek nature for its implicit, divine beauty. Finding connections with nature, with other people, and with aspects of life that aren’t inherently intertwined with consumption will help us to regain the sense of freedom we as Americans draw upon so much. These practices can detach us from our innate condition of pride-inducing anxiety, allowing us to focus on something greater than ourselves. Freedom is an aspect of the human condition that allows us to choose how we want to act – and there is a fine line between maximizing this freedom to live a life that transcends daily struggles and abusing this freedom and turning it into self-assertion. By addressing these selfish, prideful impulses, we can see how our individual actions fit into the bigger picture of our immediate community and the world, and not let history repeat itself.

References

Baer, R. A. (1976). Our need to control: Implications for environmental education. The American Biology Teacher, 38(8), 473-476. doi:10.2307/4445695

Britannica. (n. d.). Hudson River school. Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/art/Hudson-River-school

Cronon, W. (1983). Seasons of want and plenty. Changes in the land. Hill and Wang.

Dobson, D. (2013). Manifest destiny and the environmental impacts of westward expansion. FJHP, 29, 41-69. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/81291419.pdf

Ellis, J. W. (2019). “Forest cathedrals: “The hidden glory” of Hudson River landscapes. Journal of Religion & Society, 21, 1-20.

Gilpin, W. (1860). The central gold region. Sower, Barnes & Company.

Heidler, D. S., & Heidler, J. T. (2020, March 20). Manifest destiny. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Manifest-Destiny

Hiebert, T. (1996). Rethinking dominion theology. Direction: A Mennonite Brethren Forum, 25(2), 16-25. https://directionjournal.org/issues/gen/art_922_.html

History.com Editors (2019, September 30). Westward expansion. History.com. https://www.history.com/topics/westward-expansion/westward-expansion

Lee, R., & Ahtone, T. (2020, March 30). Land-grab universities. High Country News. https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.4/indigenous-affairs-education-land-grab-universities

National Archives (2019, December 12). The Homestead Act of 1862. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/homestead-act

Niebuhr, R. (1939). Man as Sinner. The nature and destiny of man: A Christian interpretation. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

PBS (2001). William Gilpin. https://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/d_h/gilpin.htm

Schmidt, C. W. (2004). Sprawl: the new manifest destiny? Environmental Health Perspectives, 112(11), 620-627. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.112-a620

Seiferle, R. (2017, October 15). The Hudson River School Movement Overview and Analysis. The Art Story. https://www.theartstory.org/movement/hudson-river-school/

U.S. Forest Service (2001). U.S. forest facts and historical trends, https://www.fia.fs.fed.us/library/brochures/docs/2000/ForestFactsMetric.pdf

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (n.d.) Timeline of the American Bison, https://www.fws.gov/bisonrange/timeline.htm

Wilsey, J. D. (2017). “Our country is destined to be the great nation of futurity”: John L. O’Sullivan’s manifest destiny and Christian nationalism, 1837-1846. Religions, 8(68), 1-17. doi:10.3390/rel8040068

- In addition to the sin of religious pride, Niebuhr also suggests that pride of power can be a sin of self-assertion. Niebuhr (1939) states, “Sometimes this lust for power expresses itself in terms of man’s conquest of nature, in which legitimate freedom and mastery of man in the world of nature is corrupted into a mere exploitation of nature.” Here, he is emphasizing the fact that this pride of power can lead humans to overexploit nature and others, believing that using their power over the less powerful will alleviate their insecurity and anxiety about the human condition. This “arrogant sense of independence” is a sin of power, because instead of looking to God for help, those who are insecure find the temptation “to overcome or to obscure insecurity by arrogating a greater degree of power to the self” (Niebuhr, 1939). The combination of religious and power-driven pride might give us some insight as to why manifest destiny ideology was so popular. Not only did some believe their religious mandate to live and prosper in the West was superior to others, but they were driven by the belief that acting in this way would cure their insecurity and anxiety about the unknowns of life. ↵

- Although conditions on a homestead were not ideal for the average white settler, the struggles they faced may have been made easier through the belief that God was helping them fulfill a divine destiny. It is interesting to consider whether those who believed it to be their destiny were spurred on through their trust that God would help them face their daily struggles, or if they were so adamant that this was God’s plan, that they trusted they would succeed. The former might not be considered the religious or power-driven pride that I mention previously, but simply a humble trust in God. ↵

- The American government was also able to justify the removal of more than 250 tribes from over 10.7 million acres under the guise of the Morrill Act (Lee & Ahtone, 2020). The Morrill Act provided money from Indigenous land sales to fund the opening of dozens of “land grant universities” – including The Ohio State University. While these universities are important resources today, it is important to consider that the land sold out west to fund their construction was not acquired fairly. ↵

- Of course, hundreds of Indigenous tribes had occupied the land that was eventually set aside to become national parks and forests, and they were forcefully removed. It is difficult to unwrap the nuances of the Hudson River School movement, but it is important to remember that the preservationist movement is not completely innocent. For further discussion of these complex dynamics, see: Taylor, D. (2016) The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection, Durham and London: Duke University Press. ↵