53 Origins of the Pro-Religion, Anti-Environmentalist Conservative Stereotype

Liz Vukovic

Introduction

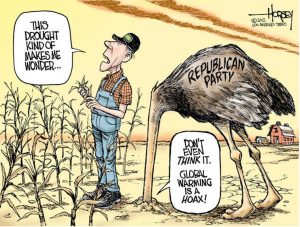

The conception of someone who is “anti-environment” usually evokes one of two images: 1) a fat cat in a suit, smoking a cigar while lining the pockets of the fossil fuel industry, or 2) a truck-driving rural American scoffing at the Prius-driving liberals in the cities who preach about their recycling practice. This chapter focuses on the second image. This political cartoon by David Horsey captures the stereotype well:

The distinction has been made clear in our minds: liberals care about the environment and conservatives don’t. This, along with another common conception that conservatives are religious while liberals aren’t, paints an inaccurate picture that drives religious conservatives out of the environmental conversation.[1] How did this happen?

As discussed by Hitzhusen (n.d.), religion has widely been understood amongst environmental thinkers as a “significantly anti-environmental force,” mostly due to repeated citations of the Lynn White thesis, which claims that the roots of the environmental crisis stem from the Judeo-Christian reading of the Bible, which suggested that man should “dominate” nature (White, 1967). White’s thesis has been refuted by plenty of scholars and theologians,[2] and Evangelical minister Tri Robinson’s reading of Genesis 9 succinctly explains why: “God established a covenant with His creation…it was a covenant which commissioned all of His people to become stewards of creation. For those who read their Bible and believe it, this should have been a no-brainer” (Robinson, n.d.).

Despite the consistent evidence suggesting a positive connection between religious views and environmental values, the contrary stereotype remains in many spaces. Where does this stereotype of the pro-religion anti-environmentalist come from? This chapter attempts to answer this question through a historical analysis of religious and American politics and a sociological analysis of the influence of group identity, framing, and rhetoric. The rise of the Moral Majority and preachers of the Prosperity Gospel during this time marks a significant turning point in our nation’s modern political history. Specific attention will be paid to social, political, religious, and existential forces at play in the mid-20th century, which allowed for a huge migration of Christians across political party lines. Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to pull out each tangled thread that contributed to the pro-religion anti-environmental stereotype, I will attempt to paint the broad strokes.

Religious and Political History

Puritan Settlers and the Emergence of the Calvinist Work Ethic

Sociologist Max Weber’s 1905 book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, was significant for its argument that the work ethics stemming from Protestantism were the cause of capitalism’s success in Northern Europe and the United States (Headlee, 2020).[3] When a wave of Protestants arrived in the United States in the 1600s in search of the freedom to practice a “purer” form of their religion (thus earning them the label “Puritans”), the ideal of the self-made man took hold in American culture (Barry, 2012; Headlee, 2020). No longer were the aristocrats and monarchs of Europe the only role models for wealth and success; in a nation seemingly free of the impacts of generational wealth, one could build an empire from nothing.

Of course, American empires weren’t made from nothing: they were built on lands stolen from Indigenous tribes and by the hands of enslaved people. The incomplete and often false nature of this narrative does not diminish the power of its influence, and speaks to the importance of storytelling in the creation of belief and value systems. The African American social reformer Frederick Douglass said in a famous 1859 speech: “My theory of self-made men is, then, simply this: that they are men of work…honest labor faithfully, steadily and persistently pursued, is the best, if not the only, explanation of their success” (Headlee, 2020). American capitalism is grounded in the belief that hard work done by the individual will always produce wealth and success, and that competition is the best way to achieve this outcome.

Puritan beliefs quickly branched into different forms of Protestant thought, including Calvinism, which combined nicely with capitalist economic theories that prioritized individual action and competition.[4] From 1620 to 1930, these themes dominated the American way of life: the rich man was rich because he worked hard, and the poor man just needed to work harder (Famer, 1964).[5] In addition to Calvinist virtues of thrift and hard work, American individualism and competition were also supported by the dominant scientific paradigms of that time. After the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s, the United States experienced what one researcher calls “the rapid application of science to industry” (Farmer, 1964). This is what Richard Baer (1976) refers to as the ratio epistemology, which views knowledge as a source of power and control. Western science and industry, Baer argues, “regards as irrelevant anything but the measurable, the quantifiable, and the empirically verifiable” (1976). After the Industrial Revolution, ratio dominated, and worldviews that supported this aggressive, analytical, and rational approach to knowledge acquisition were celebrated. The ethics of Calvinist Protestantism and competitive capitalism naturalized the roles that hard work, individualism, and maximization of wealth played in the formation and continuation of the promises of the American Dream (Farmer, 1964).

Ethics of the Social Gospel

At the same time that the Calvinist work ethic and faith in the capitalist system were joining to create “[t]he peculiar combination of ethics, religion, science, and economics” that was the hallmark of pre-WWII America, another perspective was emerging: the Social Gospel (Farmer, 1964).[6] While Calvinists were reading their Bibles and surmising that God wanted His followers to work hard and focus on their individual welfare, believers in the Social Gospel were reading the same Bible and concluding that God was advocating for helping others above all else. Both of these Biblical interpretations are valid and were developed by equally devoted members of the faith; however, the behavioral and ideological implications of each of these perspectives are vastly different. While a Calvinist may only be willing to help someone in need if the person has already proven they are willing to help themself, a Social Gospel reader may not find it necessary to discern whether an individual is “deserving” of help. These perspectives translate quite neatly into the political ideological spectrum we see today. “A liberal is a [Social Gospel] man,” Farmer explains, “convinced in his soul that we must necessarily regard all humans in the manner in which Christ treated all men” (1964). On the other hand, “[a] conservative is essentially a Calvinist, equally religious and equally ethical, but convinced that a man must find grace on his own, without help from organizations or other men” (1964). It should be emphasized that these perspectives, as Farmer said, are equally religious and equally ethical; still, they are incompatible with one another. In reality, most individuals find themselves somewhere in the middle of the spectrum when it comes to explaining the human condition: personal responsibility and social influence[7] both play a role, and the relationship between these two factors is complicated. Generally speaking, though, the dominant paradigm in the United States emphasized personal responsibility, or the Calvinist ethic, until the 1930s.

The Great Depression and WWII

Once the Great Depression quieted the calls of the American Dream for many people, it became clear that social influence played a bigger role in shaping the American economic landscape than most people wanted to believe. No matter how hardworking or driven an individual was, economic systems could collapse and put their livelihood in jeopardy. The Social Gospel that called for collective action, social welfare, and caring for one another suddenly made a lot more sense to many Americans. President Franklin D. Roosevelt implemented the New Deal in the early 1930s to alleviate the pressures of the Great Depression and established systems of social welfare to regain Americans’ trust in banks and institutions (Manza, 2000). The New Deal was a normalization of the belief that it was the duty of governments to protect its citizens from poverty and unemployment, and Americans were coming to terms with this reality. Conservative beliefs – rooted in trust in the unregulated free market– were shaken during the Depression. Still, those who believed in the value of individualism and hard work feared that the welfare state would decrease people’s motivation to work and may lead to idleness, thus threatening the Calvinist Protestant beliefs upon which many people relied (Carter, 2003). Things continued this way in the United States between the Great Depression and World War II – a cautious revitalization of the economy and unspoken unease about the moral implications of welfare – until the 1940s and 50s set the stage for a strengthening of conservativism.

Post-War Optimism Fuels Conservative Values

In postwar America, the G.I. Bill allowed newly returning veterans to afford a home by putting less money down up front and taking out longer mortgages, stretching the payments across 15 or 30 years instead of 5, which was customary. With thousands of veterans suddenly able to purchase a home, the project of suburbia began in earnest[8] Families could leave the crowded, dangerous city and take up space in their homes and on their lawns, where they were safe from the ills of urban life. This newfound isolation left “little space for or interest in a “public sphere;” instead, American individualism flourished as people spoke into increasingly shrinking echo chambers (Carter, 2003). Suburbia was the site for a modern form of community organizing, where racially, economically, and politically homogenous neighbors could meet and discuss their anxieties about communism,[9] sex education in schools, and growing racial tensions between Black and white individuals (Carter, 2003). As the 50s drew to a close, the “tumultuous and unsettling” social events of the 1960s (the Civil Rights movement, Second Wave feminism, the Vietnam War, etc.) made “millions of Americans more responsive to conservative arguments” that relied on traditional values of family, safety, respect, and order (Carter, 2003; Heaven, 1999 ). Conservativism continued to strengthen throughout the 1960s, allowing the election of the self-proclaimed “centrist” Richard Nixon in 1968; the Watergate scandal, however, likely contributed to the election of a Democrat in 1976: Jimmy Carter.

Jimmy Carter was clearly a pro-environmental president, drawing from his upbringing as a Southern Baptist and peanut farmer to inform his ethics of environmental stewardship, equality, and care for creation (Riley, n.d.). Carter’s upbringing is also what informed his appreciation for hard work and close-knit communities, and it is the rejection of these values in favor of consumerism that Carter spoke out against. “We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose,” he claimed (Carter, 1979). In the context of the oil shortages of the 1970s, Carter’s message was clear: Americans need to consume less because we may not always have the resources, and because consumption isn’t what makes us happy at the end of the day.

Reagan’s Critique, The Population Bomb, and Roe v. Wade

Although Carter’s disapproval of American consumerism was well-warranted and could be seen through a liberal or conservative lens, Ronald Reagan used this critique against Carter during the 1980 election campaign (Riley, n.d.). At the same time Reagan was asking Americans why a prosperous nation such as the United States needed to suffer by conserving and giving up our well-earned luxuries, a new political organization was being established by Christian fundamentalist Jerry Falwell (Reily, n.d.; Britannica Online Encyclopedia, 2018). Falwell, a religious leader and televangelist, named the organization the Moral Majority and focused on advancing conservative social values and establishing the religious right in the political arena (Britannica Online Encyclopedia, 2018). The Moral Majority and the Christian right in general disliked Jimmy Carter, despite his Christian faith, due to his stances on social issues such as the role of women in government and the eradication of religion in schools; for these actions, according to his opponents, he was a bad Christian (Moen, 1994 ).

In the background of Carter’s presidency was the aftermath of Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion in 1973, during Nixon’s presidency (Williams, 2011). At the time, Roe v. Wade was a fairly uneventful decision (as surprising as that may seem today), because abortion was largely divided across religious lines, not political party lines. A public opinion poll in 1976 revealed that Republican voters were actually more pro-choice on average than Democrats (Williams, 2011). In an effort to increase the Republican party’s appeal to Catholics (who, up until that point, mostly voted Democrat),[10] an antiabortion platform was adopted on the grounds that “abortion on demand” was actually a marker of the social liberalism of the 1960s and 70s rather than a health decision for pregnant individuals (Williams, 2011). This shift in attention helped nudge religious Democrats over to the Republican party, contributing to the now ubiquitous belief that one’s faith was inextricably linked to one’s politics. While Republicans were speaking out against abortion, some accounts suggest that Democrats may have been using the legalization of abortion as a pro-environmental force.

The Population Bomb by Paul Ehrlich was a 1968 best-selling book which argued that the earth was running out of resources due to the exponentially climbing worldwide population (Greenhouse & Siegel, 2019). Some environmentalists at the time took Ehrlich’s word as gospel (pun intended) and saw legalized abortion as a way to limit family size and keep the world’s population under control, thus pulling the brakes on the runaway train of our resource consumption (Greenhouse & Siegel, 2019).[11] Using abortion as an environmental tool may have shifted both abortion and environmentalism into the “liberal” camp, as the Republican party was appealing to Christians to join a conservative party that opposed abortion (Williams, 2011; Robinson, n.d.). The connections between Roe v. Wade and the “liberalization” of the environmental movement are merely suggestive at this point, but they contribute to a much larger narrative that strengthened the dichotomies of liberal/conservative, secular/religious, pro-choice/pro-life, and pro-environmental/ “anti-” environmental that we now consider intrinsic.

The Prosperity Gospel

In addition to the 1980s being a time of great division between liberals and conservatives, it was also a time of opportunity for those who were looking to “rebrand” the Christian faith to align more closely with the American Dream and ideals of consumerism. With Reagan’s neoliberal economic policies came the chance to test the “logic of the marketplace” through the success of large religious endeavors such as the megachurch and televangelism (Bowler & Reagan, 2014). On living room television sets and in packed stadiums, Christianity was being portrayed as a means by which one can achieve the ultimate ends of happiness, success, and wealth. Americans were told by the president and by preachers that they could have it all: they could enjoy riches in this life and be rewarded for it in the kingdom of Heaven. This promise became known as the Prosperity Gospel.

The roots of the Prosperity Gospel connect to many forms of faith, but took hold most strongly in evangelist Christianity, where it still thrives today. The Prosperity Gospel is based on four main pillars – faith, health, wealth, and victory –and tells its followers that worshipping God will lead to material successes and abundance here on earth, and that consumerism was an expression of one’s faith (Bowler & Reagan, 2014; Mundey , 2017).[12] Not all Christians believe in the Prosperity Gospel (most don’t), but it is not insignificant that a disproportionate number of the largest megachurches in the United States preach the Prosperity Gospel (Bowler & Reagan, 2014). Preachers like Joel Osteen, Kenneth Copeland, Oral Roberts, and the 700 Club offered Americans a “narrative of hope,” attaching a “positive view of self-interest and personal agency” in times when many felt that they were at the whims of economic and social forces much larger than themselves (Mundey , 2017).

The Prosperity Gospel itself has little to say about the environment, and one could argue that the accomplishments of the former are detrimental to the latter: they are intrinsically opposed, and it seems that this opposition is storied and complex.[13] Looking back at the history of environmental politics in the Republican party, one can see how religious language can be used to contribute both to an individualist neoliberal economic ideology and an anti-regulation environmental stance. It is not the religious language itself that enforces these beliefs (as discussed with the refutation of the Lynn White thesis and the Social Gospel reading of scripture); rather, it is the work of political or corporate entities who capitalize on people’s basic human insecurities and desire for structure, belonging, and meaning.

Environmental Politics and Religious Rhetoric

Republican Environmental Politics: From Conservation to De-Regulation

Although a majority (68%) of Americans say that the federal government is not doing enough to protect the climate or the environment, most of the members of this majority identify as Democrat or Democrat-leaning individuals (Pew Research Center, 2019). For Republican and Republican-leaning individuals, supporting environmental policies may feel like deciding between one’s values and one’s political identity. This wasn’t always the case in American politics. The First and Second Conservation Eras in the United States, which lasted from 1870 to 1959, featured the establishment of the first National Park, the beginnings of the Conservation and Preservation movements, and the building of the transcontinental railroads (Steele, 2020). Some of the most influential actions in these eras were enacted by Republican presidents or under a Republican-majority Congress: the Antiquities Act was signed in 1906, the National Parks Service was created in 1916, and the National Air Pollution Control Act was created in 1955 (“Timeline,” 2020). Even as late as the 1970s, environmental policies were generally supported by both political parties equally, as evident in the fact that Republican president Richard Nixon established the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Clean Air Act (Rinde, 2017). With Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign, environmental issues began settling distinctly on one side of party lines. As one of the administration’s major policy goals, Reagan worked to deregulate the federal government, which included a mass resignation of EPA officials in 1983 (Lynch, 2001). It should be made clear that it was regulation that Reagan opposed, not the environment itself. Opposition to environmental regulation expressed by Republican politicians can oftentimes be categorized as opposition to regulation in general, which is thought to stunt economic growth.[14]

Environmental regulation (and the environmental movement in general) can be framed as a scapegoat, as a cause for economic decline in many parts of the country. This is especially true in rural America, where a large portion of the economy is based in resource-intensive industries such as coal mining and timber harvesting (Dillon & Henly, 2009). On the other hand, this economic prosperity also means that individuals in rural America are particularly under threat by the imminent consequences of climate change, which threatens the long-term use of fossil fuels. This fact is unsurprising, especially in the context of Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’, in which the Pope, drawing upon scientific research, says that “many of the poor live in areas particularly affected by phenomena related to warming.” What is inconsistent with this sentiment is the fact that “born-again Protestants are the least likely [religious affiliation] to express attitudes favoring environmental conservation,” specifically born-again Protestants in areas of economic decline (Dillon & Henly, 2009). This may be attributable to the fact that rural Americans facing economic hardships are looking at outside sources to explain their position. “The increased attention in the media and in corporate advertising” argue researchers Dillon & Henly, “may make anti-environmentalism a readily accessible way for religiously conservative rural Americans in declining communities to resist the economic changes around them” (2009). It is not only these corporate advertisers who stand to gain from blaming economic decline on environmentalism. “Rural voters are also often the swing vote in close elections,” meaning that they garner close attention from political candidates looking to secure crucial votes (Dillon & Henly, 2009). This puts rural Americans in a vulnerable place, subject to the environmental degradation fueled by climate change, economic decline from resource depletion, and personal, targeted persuasion from politicians and advertisers.

Members of political office possess a great deal of power, both in legislation and in their ability to produce and reinforce specific worldviews amongst the American public. It is not a coincidence that religious beliefs and conservative ideology are correlated, nor is it a coincidence that secular beliefs and liberal ideology are correlated. As the opposing ends of the political spectrum move farther and farther apart, politics and media reflect the values of each opposing end and work to strengthen the extreme beliefs of American citizens. Those who hold strong political beliefs tend to be more politically active than moderate individuals. This means that politicians have everything to gain from contributing to political extremism. Animosity, passion, and allegiance to a group or larger cause will win more votes than any singular policy or candidate ever could. For an anti-regulation conservative, voting against environmental policies may be an easy choice, just as it may be an easy choice for a pro-equality liberal to vote against the presence of religion in public schools.

Religious Language as a Political Tactic

In order to understand the influence of religion on American culture, it will be helpful to first examine how religion is embedded into the everyday life and language of the average American. Civil religion, a term coined by Robert Bellah, describes “a set of beliefs, symbols, and rituals” utilized by society to “interpret its historical experience” (1967). In other words, civil religion is a lens through which to view the world and explain the complex, seemingly unexplainable aspects of history. The use of civil religion can be “indicative of deep-seated values and commitments” that may be unnoticed in everyday life, but nevertheless affect how the American population acts and votes (Bellah, 1967). Civil religion used to be considered benign and unrelated to specific partisan motivations in American politics: it was a ceremonial tactic used to make political language sound more official and traditional. The importance of civil religion became apparent in 1960, with the election of the first — and, until the election of Joe Biden in 2021, only — Catholic president: John F. Kennedy. Addressing concerns that a Catholic president would be used to carry out an agenda set forth by the Vatican, Kennedy gave a speech to a conservative Protestant clergy. In this speech, he said, “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute” (Domke & Coe, 2007). The unifying language of John F. Kennedy holds a stark contrast to a declaration made by Jerry Falwell, founder of the Moral Majority, during the 2004 U.S. presidential campaign: “For conservative people of faith, voting for principle this year means voting for the re-election of George W. Bush. The alternative, in my mind, is unthinkable” (Domke & Coe, 2007 ). Political polarization has forced a wedge between people of faith, sending them to the ends of party lines that obfuscate their shared underlying morals.

According to the largest political survey ever conducted, the Pew Research Center has concluded that “growing numbers of Republicans and Democrats express highly negative views of the opposing party,” and those who are more strongly oriented in their ideology tend to vote more often and donate more to political campaigns than individuals with moderate ideologies (Pew Research Center, 2014a). The evidence is clear: political polarization in America is on the rise. This means that politicians can benefit from speaking directly to one side or the other, rather than remaining moderate, which would fail to engage either side of the ideological spectrum. Even though this may do more to exacerbate polarization rather than unite Americans, it would strengthen the support of a candidate from one side. “In part, the desire to hear presidents speak their language stems from concerns among many religious believers, particularly fundamentalists and conservative evangelicals, about the secularization of modern society” say researchers Domke and Coe (2007). While religious language has been a part of American politics since the very first day of the country’s founding, a dramatic spike in 1981 made a clear attempt to capitalize off the concerns of religious Americans. Between 1933 and 1980, roughly 50% of presidential addresses to the nation included some reference to God or religion, and from 1981 to 2007, this percentage jumped to over 90% (Domke & Coe, 2007). Although there are many possible reasons as to why this sudden change occurred with the Reagan administration, researchers have identified three potential main influences: wartime context, whether a candidate is facing re-election, and being a member of the Republican party (Domke & Coe, 2007). While it is true that not all religious individuals are politically conservative, it is more likely that Christians and Protestants are politically conservative than any other political ideology (Pew Research Center, 2014b). Using this information, one can begin to see why a Republican candidate seeking re-election during times of unrest would utilize religious language: it has the potential to persuade a large number of voters.

Sociology and Existentialism: The Need for a Center

Our Anxiety: Do We Matter?

Any historical exploration benefits from clarification on how the human experience is perceived: what drives people to do the things we read about in history books? How can these events be seen as examples of our human needs and nature? In his book The Nature and Destiny of Man, Reinhold Niebuhr describes the human experience as one of conflict between a finite life and one’s free will and imagination (1943). As we contemplate our own mortality, we also attempt to transcend it through pridefulness and a naïve belief that we can somehow break free of our biological and psychological limitations. Philosopher David Loy describes this existential anxiety using the Buddhist concept of dukkha, which translates to “suffering” or “un-satisfactoriness” (Loy, 2010). The very definition of being a human, Loy explains, is dealing with our dukkha and all the ways we try to avoid it. This dukkha stems from our inability to understand the concept of anatta, or the not-self (Loy, 2010). Richard Baer critiques Americans in particular for the ways in which we have made death taboo. Our fear of death, as a result of our unwillingness to confront it, leads to a compulsive need to control our situation on Earth, which leads to unthoughtful action and domination of the environment and of other beings (Baer, 1976). Philosopher Steve Hall describes humans as being powered by a “life-force,” or a desire to live on in the things we create and the purposes to which we dedicate ourselves; however, humans are also mired with an “objectless anxiety,” caused by turmoil or stresses in life and exacerbated by the promises that one ideology over another can give us the key to transcendence and living on (Hall, 2012). All of these perspectives share the same core tenets in common: the human desire to matter. We need a center around which to base our lives, to provide us with a sense of truth and meaning, and to answer the “big questions” we have. There are countless ways we define and reaffirm our importance: the communities we identify with are one example.

The Need to Belong

It feels like an obvious truth to claim that when an individual considers themselves to be a part of a group, they are more likely to agree with that group than oppose them. Heaven (1991) sums it up simply: “The groups to which individuals belong — political, ethnic, or religious — help shape their self-definitions and, consequently, their identities.” Group identification in and of itself is not a negative thing. Adhering to a group identity provides us with an increased sense of belonging, facilitated connection with other members of our same groups, and a strong set of values and beliefs upon which to fall during times of distress or uncertainty.

Religion can be an incredibly powerful group identity that can provide individuals with a system of belief and understanding that passes from generation to generation, resulting in a sense of collective meaning that spans throughout history and looks forward to the future (Domke & Coe, 2007). In addition to being a system of symbols, religion is also a form of storytelling. The stories we tell about who we are, how the world works, and what matters most serve as our foundation for what is true and real. The stories that we believe in forge deeper and deeper pathways in our thinking, language, and culture. As stories are retold and remembered over time, these pathways become more difficult to stray from. The more rigid one’s belief system, the more specific and narrow it gets, which leaves the world full of conflicting views. This confliction can feel overwhelmingly close to chaos, and the ability to look to a larger body for advice on what to think, feel, and believe can help us navigate that chaos. When group identification gives way to tribalism, however, these benefits disappear, and animosity and intergroup conflict increases.

The identification of a “self” within the context of a group necessitates the oppositional “other,” or whatever is not the self. According to Loy, such “collective senses of self are often problematical, because they…distinguish those of us inside from those who are outside” (2010). The process of distinguishing in-groups and out-groups does not inevitably lead to tribalism and conflict, although Loy points out that “those of us who are inside are not only different from those outside; we like to think that we are better than them” (2010). It is difficult to identify with a group without assuming that that group has figured out the “right” way to see the world.

Values and Political Ideology

Religious, political, and environmental beliefs are often contentious viewpoints, largely due to the fact that these beliefs are strongly tied to one’s values. In the field of social psychology, values are defined as “concepts or beliefs about desirable end states or behaviors that transcend specific situations, guide selection or evaluation of behavior…and are ordered by relative importance” (Schwartz & Bilsky, 1987). There are many values that any individual may hold, but for the purposes of environmental and political psychology, values can be categorized into four general themes: conservation, self-enhancement, self-transcendence, and openness to change (Dietz, Fitzgerald, & Shwom, 2005). Values of conservation, for example, may include values of family, safety, self-discipline, and respect, where values of self-transcendence may include social justice, unity, protection, and equality.

The values an individual holds are influenced by the types of media one consumes, the values of family and close friends, and one’s occupation, to name a few. The values one holds are also heavily influenced by the groups with which one associates, and political party is no exception. “People intending to vote for left-of-center parties” tend to hold values that endorse “international harmony and equality more than they [endorse] national strength and order,” which are values most typically “reserved for right-of-center voters” (Heaven, 1999). If those who uphold a more conservative ideology tend to value strength, family, and respect, it makes sense that economic prosperity is regarded with high importance by conservatives, as economic prosperity brings strength and safety to an individual and their community. On the other hand, if those who uphold a more liberal ideology tend to value equality, harmony, and social justice, it makes sense that environmental prosperity is regarded with high importance by liberals, as environmental prosperity brings about harmony and justice.

The more strongly affiliated one becomes with a political party or ideology, the less likely it is that that individual will look across the aisle and attempt to see things from another point of view. This is true for all people, regardless of specific political affiliation. Care for the environment and expressing religious beliefs are not mutually exclusive, as mentioned earlier with regard to Hitzhusen’s (n.d.) research, but society continues to tell individuals through advertising and political discourse that caring about the environment is only for liberals and going to church is only for conservatives. This reinforces the false narrative that one cannot love both their God and their planet. When the values an individual conflicts with the values of the group with which one identifies, one is forced to choose between their values and their identity. This is not an easy decision, nor is it one anyone should have to make.

The Importance of Framing

In a study aptly titled “Red, white, and blue enough to be green,” researchers at Oregon State University found that “widespread political polarization on issues related to environmental conservation may be partially explained by the chronic framing of persuasive messages…that hold greater appeal for liberals” (Wolsko, Ariceaga, & Seiden, 2016). When environmental attitudes are framed in a way that appeals to conservatives, values such as “loyalty, authority, purity, and patriotism” are emphasized (Wolsko, Ariceaga, & Seiden, 2016). Even though the foundation of the environmental statement remained the same, when test subjects perceived the message to be coming from a member of their in-group, they were more likely to support the message. This is intuitive insofar as a person is more likely to agree with a message if it is coming from someone they trust and relate to.

The findings of Wolsko, Ariceaga, and Seiden are promising and can provide hope for those looking to bridge the gap between religious pro-environmentalists and religious conservatives who may be against environmental regulation. Humans are not always rational creatures, and decision-making is often guided by unconscious cues from our surroundings. For lobbyists, activists, speakers, and politicians, paying attention to the values that are conveyed in statements can be an effective way to ensure the essence of a message is being communicated instead of unrelated judgements of groups or ideologies.

Conclusion

Recommendations for Further Research

In order to continue on the path of defining and solving such a complex mess of problems, it will certainly be necessary to gain more clarity on the historical developments that have led to such entrenched political polarization and consumerist ideology in the United States. Here are some questions I was not able to fully explore, but nonetheless feel are relevant pieces to this ever-growing puzzle:

- How did the environmental movement become associated with liberals in the first place?

- How can we lift up examples of conservative environmentalists without alienating those who hesitate to use terms like “climate change” for fear of being associated with an opposing political ideology?

- What are the links between Roe v. Wade and population control arguments? Are there many examples of this?

- How significantly did the Prosperity Gospel influence Christians’ perception of materialism, if at all?

- What are the Christian perspectives on free-market capitalism throughout history?

- What obligation do we have to adhere to the teachings of a faith when we claim to be a member of that faith? Should a believer of the Prosperity Gospel be allowed to call themselves Christian when their beliefs directly contrast Jesus’ teachings of care for the poor, sick, and vulnerable?

- Would a revision of the methods of teaching Christianity allow for a more unified view among sects?

- How has marketing and advertising contributed to our existential anxiety by falsely conflating buying things as the key to happiness and satisfaction?

- To what extent might the term “environmental” be divisive and be contributing to the problem, as it is almost always associated with liberal political views and therefore might not be a desirable goal for all?

- How can attention, mindfulness, and “opting out” of unsustainable systems affect people’s religious or environmental views?

- Have politicians capitalized on religious peoples’ “end time” beliefs to incite fear, urgency, or complacency amongst important voter demographics?

Where This Leaves Us

The stereotype of the pro-religion, anti-environment conservative is, like all stereotypes, both inaccurate and incomplete. It is a natural human instinct to identify with those who are like us and reject those who are dissimilar, as it was likely advantageous for our ancestors to do so to ensure safety for their community and reduce intergroup conflict. Humans in the hunter-gatherer era identified with only one group: their immediate family. In our modern era, there are endless groups we can join: we place ourselves in a box for our nationality, our religion, and our political affiliation, to name a few major groups. The more groups people are a part of, the greater the chance of conflict between differing groups. Up until the 1950s or so, the Dominant Social Paradigm in the United States was white, heterosexual Protestantism. A majority (if not all) of the most powerful individuals in the social order matched this description, to the point where these identities were seen as ubiquitous, as the default way to be a human. As the 1960s paved the way for social change and acknowledgment of the country’s diversity, the Dominant Social Paradigm began to collapse, but the desire to have a Dominant Social Paradigm remained. We now find ourselves in a situation where false dichotomies are pitted against one another (conservative/liberal, Republican/Democrat, white/non-white, etc.) and are encouraged to fight for the spot at the top, to become the Dominant Social Paradigm.

Rather than imagining others complexly, as a unique combination of an infinite number of traits, beliefs, and experiences, we reduce a person to whatever group is convenient for us in that moment. It is easy to judge someone based on their membership in a specific group, but it does not tell the whole story. Labels are inherently limiting; by identifying as one thing, someone is also not identifying as anything that conflicts that one thing. To call yourself a Christian means you are decidedly not an atheist, Muslim, Jew, Sikh, or any other religious affiliation. The labeling gets complicated when others hear the word “Christian” and assume that that also means you are not liberal, pro-environment, or anything else not commonly associated with Christians. By looking more closely at the underlying assumptions we make about others, we can move towards a more inclusive environmental movement that is beneficial for everyone involved.

To say that dispelling the stereotype of the pro-religion, anti-environment conservative would solve the environmental crisis is obviously untrue. There is no silver bullet that will cause everyone to suddenly see eye-to-eye and join forces against the changing climate or the consumerist ideologies that pervade the social order. Approaching one solution (and there are countless) is too much to cover in a lifetime, let alone a conclusion paragraph; however, I can still provide the things I’ve found relevant and that have given me hope around this issue.

In Richard Baer’s argument that our need to control leads to domination of other beings and the environment, Baer explains that “the healing of nature will only come about with the healing of persons” (1976). According to Iris Murdoch and David Loy, it is through the attention we pay to others that we can dissolve the illusion of the “self” and interact with the things that matter most: beauty, love, and truth (Hauerwas, 1974; Loy, 2010). This experience of “unselfing” comes about by doing things for their own sake and for others. Unselfing allows us to temporarily set aside our biases and prejudices and get a more accurate vision of the others’ perspectives, which in turn contributes to shared understanding instead of conflict. Unselfing also allows us to realize the shaky ground upon which all of our identities stand. In embracing the inherently dependent nature of the self and recognizing how other beings and systems make us who we are, terms like “liberal” and “conservative,” for example, seem far less salient or foundational to our identity. When we forget about our own desires and turn our attention outward, we engage in the process of striving toward meaningful connections and experiences.

Ultimately, the dispelling of the pro-religion anti-environment conservative stereotype can begin to be addressed through one basic tactic: empathy. Through empathy, we momentarily forget ourselves and adopt the experiences of another person. We imagine why we would consider the decisions we make to be rational ones, why the things we value are important, and why we regard ourselves as good people. Rather than labeling those who are different from ourselves as evil or deluded, we should do our best to imagine why others think their choices are right and their groups are the best ones. In doing this, we may also identify shortcomings or fallibility in our own worldview and arrive at a more holistic understanding of the world, those around us, and our relation to one another.[15]

References

Baer, R. (1976). Our need to control: Implications for environmental education. The American Biology Teacher, 38(8), 473-476.

Barry, J.M. (2012). Roger Williams and the creation of the American soul: Church, state, and the birth of liberty. Penguin Random House.

Bellah, R. (1967). Civil religion in America. Daedalus, 96(1), 1-21.

Bowler, K. & Reagan, W. (2014). Bigger, better, louder: The Prosperity Gospel’s impact on contemporary Christian worship. Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, 24(2), 186-230.

Britannica Online Encyclopedia. (2018). Moral majority. Enclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Moral-Majority

Carter, D.T. (2003). The rise of conservatism since World War II. Organization of American Historians (OAH) Magazine of History, 17, 11-16.

Carter, J. (1979). Crisis of confidence [speech]. Miller Center, University of Virginia.

Dietz, T., Fitzgerald, A., & Shwom, R. (2005). Environmental values. Annual Review of Environmental Resources, 30, 335-372.

Dillon, M. & Henly, M. (2009). Religion, politics, and the environment in rural America. Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire 3, 1-8.

Domke, D. & Coe, K. (2007). The God strategy: The rise of religious politics in America. Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 42(1), 53-75.

Etzdrodt, C. (2008). Weber’s Protestant-ethic thesis, the critics, and Adam Smith. Max Weber Studies, 8(1), 47-78.

Farmer, R.N. (1964). The ethical dilemma of American capitalism. California Management Review, 6(4), 47-58.

Francis (2015). Laudato Si’. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Greenhouse, L. & Siegel, R.B. (2019). The unfinished story of Roe v. Wade. Reproductive Rights and Justice Stories (forthcoming).

Hall, S. (2012). The solicitation of the trap: On transcendence and transcendental materialism in advanced consumer-capitalism. Human Studies, 35, 365-38.

Haurwas, S. (1974). The significance of vision: Toward an aesthetic ethic. In Vision and virtue (pp. 30-47). University of Notre Dame Press.

Headlee, C. (2020). Do nothing: How to break away from overworking, overdoing, and underliving. Harmony Books.

Heaven, P. C. L. (1999). Group identities and human values. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139(5), 590-595.

Hitzhusen, G. (n.d.). Religion and environmental values in America. Retrieved from https://osu.instructure.com/courses/98196/pages/star-star-online-textbook-chapter12?module_item_id=5644189

Loy, D. (2010). Healing ecology. Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 17, 253-267.

Lynch, C.M.C. (2001). Environmental awareness and the new republican party: The re-greening of the GOP? William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review, 26(9), 215-242.

Moen, M.C. (1994). From revolution to evolution: The changing nature of the Christian right. Sociology of Religion, 55(3), 345-357.

Manza, J. (2000). Political sociological models of the U.S. New deal. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 297-322.

Mundey, P. (2017). The Prosperity Gospel and the spirit of consumerism according to Joel Osteen. Pneuma, 39(3), 318-341.

Niebuhr, R. (1943). The nature and destiny of man. Prentice Hall PTR.

Pew Research Center. (2014a). Political polarization in the American public. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/06/12/7-things-to-know-about-polarization-in-america/

Pew Research Center. (2014b). Religious landscape study. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/political-ideology/c

Pew Research Center. (2019). U.S. Public views on climate and energy. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/11/25/u-s-public-views-on-climate-and-energy/

Riley, R. (n.d.). President Carter’s environmental roots. In Religion and environmental values in America. Retrieved from https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/enr3470/chapter/president-carters-environmental-roots-by-robert-riley

Rinde, M. (2017). Richard Nixon and the rise of American environmentalism. Science History Institute. Retrieved from https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/richard-nixon-and-the-rise-of-american-environmentalism

Robinson, T. (n.d.). Answering the question – How did issues concerning social justice and environmental stewardship become demonized by much of the Evangelical world? Retrieved March 26, 2022, https://trirobinson.com/answering-the-question-how-did-issues-concerning-social-justice-and-environmental-stewardship-become-demonized-by-much-of-the-evangelical-world/

Schwartz, S. H. & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 550-562.

Social Gospel. (n.d.). Retrieved April 18, 2022 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_Gospel

Steele, C. (2020). An analysis of U.S. federal environmental legislation in the nineteenth, twentieth and beginning twenty-first centuries, with emphasis on presidential party and political majorities in congress. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 26(2), 295-313.

Stoll, M. (2015). Inherit the holy mountain: Religion and the rise of American environmentalism. Oxford University Press.

Timeline of major U.S. environmental and occupational health regulation. (2021, April 22). In Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_major_U.S._environmental_and_occupational_health_regulation

White, Lynn. (1967). The historical roots of our ecological crisis. Science, 155(3767), 1203-1207.

Williams, D.K. (2011). The GOP’s abortion strategy: Why pro-choice republicans became pro-life in the 1970s. Journal of Policy History, 23(4), 513-539.

Wolsko, C., Ariceaga, H., & Seiden, J. (2016). Red, white, and blue enough to be green: Effects of moral framing on climate change attitudes and conservation behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 7-19.

- My identity as an environmentalist is entangled in my liberal political beliefs, but it never sat well with me to write off all conservatives as “anti-environmentalist.” My father, who leans more conservative, was my first exposure to environmental stewardship: he instilled in me values of conservation and appreciation for the natural world. My relationship to faith complicated things further: why does every Christian I talk to appreciate and respect God’s creation, but the environmentalist’s perception of Christianity ran so contrary to my real-life experience? These questions were the fire that fueled this research. ↵

- In fact, according to Mark Stoll, the roots of the modern environmental movement in the United States are connected to Christianity. For example, John Muir, Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, Rachel Carson, and Edward Abbey were all raised Presbyterian, a branch of Christianity that prizes conservation (2015). ↵

- It should be noted that Weber’s writing on the Protestant Work Ethic has been criticized for being an insufficient explanation for the creation of modern capitalism (Etzrodt, 2008). Still, Weber’s work is widely known and has influenced the American cultural perceptions of work and earning and is worth mentioning for this discussion. ↵

- Perhaps it is more accurate – for the purposes of this work, at least – to use the terms “Calvinist work ethic” or “Calvinist Protestantism” when referring to the religious perspective that emphasizes thrift, hard work, individual action, and the amassment of personal wealth. This distinction differentiates the overtly religious view on hard work and the mostly secularized “Protestant work ethic” that is still encouraged in American culture. In other words, the Calvinist work ethic serves God, and the Protestant work ethic serves the dollar. ↵

- Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations did an incredible job of emphasizing the role of individual action. As individuals pursued their self-interests, Smith argued, the entire social order would benefit from economic competition, which would produce the most efficient outcomes for producers and consumers alike (Farmer, 1964). Of course, the “pure” competition Smith idealizes in his work was not the reality of American economics. For pure competition to exist, an economy must meet very specific criteria which few modern industries actually achieve, such as: a large enough market to prevent one buyer or seller from affecting the market, transparency among buyers and sellers to allow for rational decision-making, and prevalence of the full employment of resources (Farmer, 1964). ↵

- Farmer refers to the interpretation of Biblical text that ran parallel to the Calvinist ethic as a “Judeo-Christian” ethic. Since Calvinism itself is a sect of Protestantism and therefore included in the general understanding of the term “Judeo-Christian,” using both of these terms can be confusing. In an effort to better separate these two ideologies, I have chosen to use the term “Social Gospel” to replace the Judeo-Christian ethic, as it is a well-known term that encompasses the same values of social welfare, care for the poor, etc. (“Social Gospel,” n.d.). ↵

- This is a rehashing of the never-ending nature vs. nurture debate that exists in the natural and social sciences. ↵

- It should be noted that the G.I. Bill has been traced back by historians to be the root of racially segregated housing, as Black veterans were denied loans or had their housing offers rejected in many new suburbs. The effects of this explicit prejudicial treatment are still visible today and are too numerous to discuss in depth in this paper. ↵

- The “Red Scare,” or the American anti-communist movement, was also strong during the 1950s and 60s. ↵

- This makes sense when we remember Farmer’s distinction between Calvinists, whose moral closely aligned with conservatives, and believers of the Social Gospel, whose values resembled those of liberals. Catholics were operating under a Social Gospel worldview that emphasized care for the poor and vulnerable, something they shared with the Democratic party who supported social services such as welfare. ↵

- Using population control as a method of environmental management, although it seems logical on its face, detracts from the main issue of our growing populations: increasing consumption. The carrying capacity of our human population (if we could even theoretically determine such a thing) is strongly correlated to the amount of resources each person consumes, which is a far more direct indicator of our global environmental impact. It is perhaps unsurprising that the population control argument has mainly been used by white, upper-middle class environmentalists, whose own consumption is often far beyond that of families in developing nations, which are the ones being critiqued for their lack of population control. ↵

- For example: one preacher of the Prosperity Gospel, Joel Osteen, tells his followers that they should keep up with the latest fashion trends by “habitually buying a new wardrobe,” and that women should shop at Victoria’s Secret to make themselves “look like the masterpiece God made [them] to be” (Mundey, 2017) ↵

- It should be noted that this research on the Prosperity Gospel is among the broadest of brush strokes in this paper and looking more into the Prosperity Gospel’s influence on the environment could provide enough material for an entire book (or a term paper, for future ENR 3470 students). ↵

- Of course, the health of the planet is not inherently opposed to the health of the economy. The “environment vs. economy” dichotomy is limiting, and often does more work to further entrench people’s political beliefs than it does to start a meaningful conversation. If someone is conservative, they are encouraged to support the free market, oppose government regulation, and prioritize growth of the economy. A liberal, on the other hand, is encouraged to support pro-environmental regulations and oppose unchecked economic growth. The “environment vs. economy” dichotomy, is, like most dichotomies, false, and detracts attention from the possibility of cooperation between these two forces. ↵

- In the spirit of recognizing our similarities, I’d like to thank my dad for taking me to Yellowstone when I was 12 years old and for always reminding me to turn off the lights when I leave a room. My environmental views came from you, and the path I am on now is because we share an appreciation for startling landscapes and sharing meaningful moments with the ones we love. Thank you for everything you’ve taught me. ↵