3 Reconnecting with Creation through Regenerative Agriculture

Emerson Gifford

I’m Emerson Gifford. The idea of writing about sustainable agriculture came from a book I came across called Growing a Revolution: Bringing Our Soil Back to Life by David Montgomery. Introducing myself into the world of regenerative agriculture changed my class and career path for the better, because I believe the practice is a powerful option for climate capture and as an option to reverse climate change. As a powerful way to reconnect with nature, studying regenerative agriculture also reignited my receding connection to religion…read more.

Introduction

For tens of thousands of years, humans have survived in many environments all around the world. Through thick and thin, humans have been able to fight against predators, weather, and starvation. The unlikely survival of humans can be heavily attributed to one thing: agriculture. With a stable food source, people have been able to do almost everything, live almost anywhere, and support billions of hungry stomachs all across the world. Agriculture is the science of cultivating plants or animals for human use, and it hasn’t changed much since the beginning. Starting around 9500 BCE, humans planted crops for a controlled harvest, planting rice, grains, and chickpeas for stable and healthy societies in the Middle East.

Almost 12,000 years later, I continue to perform the same actions in my own backyard, with very little changes. I started a garden with my Dad about 10 years ago. We squared off a 3×1 meter section of my yard, lining the outside with some decayed logs we found in the park. Carefully, the two of us buried seeds from pocket-sized bags we got at a garden store. I was sure to spoil them with loads of fresh water from inside the house every morning. I checked multiple times a day to see if I could spot any green sprouting through the brown. When there was nothing to see, I prayed and asked God to show some sprouts soon, just as the ancient civilizations I had learned about in school would do. Even after some small issues with hungry rabbits and a premature harvest, the whole idea of growing your own food from nothing but soil, water, and sunlight just fascinated me. Now, I’m much more experienced, and I still grow my own vegetables every year, even in a tiny studio apartment.

My Dad always reminded me to thank God for gifting us with healthy crops. I prayed every day for happy and healthy vegetables, as everything we did was in one way or another related to our religion. I was raised in a Lutheran church with close ties to the head pastor. He was a close family friend, and his wife was my elementary school music teacher. Everything and everyone in my church was relatively conservative. Very little in the world could be explained without using the words “Because God…”. Almost everyone in my tight-knit community went to this church, so even my public school had strong religious roots in the teachings. Science was certainly taught, but much of it was filtered through heavenly lenses. Sex was judged by God, Earth was created by God, and life was controlled by God. From what I had been taught, nothing could be done without His interference.

My education was broadened when I left my public school, mostly because of bullying. I enrolled in Metro, an early college high school on Ohio State’s campus that focuses on STEM. While at Metro, for the first time in my life, I was in the minority. Most of the students weren’t white, and Christianity no longer surrounded me. With Metro being a STEM school, I quickly learned how math and science control the world, not God. My Christian faith slowly didn’t make much sense anymore. I had grown a strong wall between science and religion. To me, the two terms had absolutely nothing in common. Like many students my age, I decided I would drop my faith and become an atheist. It seemed like the best way to ‘get back’ at my church for what I saw as hindering my education; however, my excursion into atheism did not last long.

A few years later, as a student at Ohio State, I learned in my history classes that many civilizations connect agriculture to God and spirituality. Agriculture was a form of communication, whether that be droughts for punishment or plentiful crops as a gift. I was surprised to learn that soil, while often overlooked, is the most important part in agriculture’s connection to a God’s creation. For the first time in a while, I had started making connections between science and religion, and I was eager to learn more. In my research, I found the book, Growing a Revolution by David Montgomery to be a very fascinating introduction into the dangers of traditional agriculture and the damage it does to our soil. He wrote about an interesting “new” way of farming called regenerative agriculture, and how many farmers like to use it as a way of connecting their botanical scientific journey to God’s creation. In reading this book and others, I realized that I didn’t have to be atheist to trust in science. I learned that soil health is the power behind healthy crops and a healthy planet, and maybe even the power behind a healthy relationship to creation, too.

Soil is Alive

The secret to healthy crops is in the soil in which they are planted. Many people, like me, thought the recipe for healthy plants comes mostly from water and sunlight, but the soil is the spine that keeps the plants strong and provided with stable nutrients. There are more than 6 billion organisms in every handful of soil, almost as many as the people on Earth. Every last organism, along with the nutrients they provide, has a purpose in keeping plants healthy. Not only do decomposers compost dead organic material, but most of the microscopic life in the soil supports an incredible ecosystem that can be compared to the biodiversity above ground. Most of these organisms keep a balance of carbon, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen, while also exchanging sugars with the roots of the plants that live among them (Brady et al., 2019). Soil also has the important role of preventing erosion. What we call “healthy soil” in much of the world is dense, dark brown, and doesn’t break apart easily. It packs tightly together, retaining water molecules between the granules, instead of loosely being swept away by rainfall and floods.

In much of the agriculture community an issue is arising where soil is being slowly destroyed through a multitude of causes, mainly because of tilling. Many farmers are being left with light brown sandy-like soil with almost zero microorganisms present. It doesn’t hold nutrients, carbon, or water well, causing massive erosion on many farms as the topsoil is swept away by rainfall. Scientists around the world, some of the first being from The Ohio State University, are placing the blame on our habit of tilling the soil before planting (Montgomery, 2017). Tilling is typically done by attaching massive blades to the back of tractors or horses and slicing through or mixing the soil before replanting seeds. This seems like a good idea, and for the first few years, studies have shown that tilling provides a higher crop yield. Over time, however, tilling destroys the microorganisms and cover crops that keep the soil healthy. Scientists have been seeing major issues with our modern soil. Not only are thousands of farmers struggling with dropping crop yields, many farms are seeing erosion at an alarming rate. As soil erodes, rivers that used to be clear, such as Columbus’s Olentangy River, over the past few hundred years have turned a muddy color, while also carrying pesticides and fertilizer causing a sharp rise in dangerous algae (Brady et al., 2019).

In the past few decades, scientists have noticed another issue with soil destruction. Much of the soil in America, for example, contains around 8% organic carbon. As soil is kept in place by cover crops and trees, this carbon is a healthy contribution to the structural integrity of the soil. As farmers till the soil, however, this carbon is released into the air. Carbon from soil is becoming an alarming contributor to climate change (Brady et al., 2019). We can even visualize the amount of carbon that is released from tilling, as a recently released super-computer model from NASA shows. Carbon in the animation is colored red, and in early spring and summer, the Northern Hemisphere erupts in a dark red hue, not just from typical pollution, but mainly from tilling our soil (NASA Goddard, 2014). Soil in nature, you could say as God’s creation intended, is covered and untouched. Disturbing the soil causes a multitude of issues for the environment, not just on a small scale.

Agriculture Throughout History

As discussed earlier, agriculture has not changed much over the past few millennia. Although the modern till was introduced to the agriculture scene in the early 19th century, tilling is just a more efficient way of plowing fields, which has been happening for centuries. Soil disturbance has always been a major part of farming, and the plow was a simple way to overturn crop debris for the next planting season. Until recently, humans had not seen major issues with tilling. Looking back through history, however, historians have been able to spot many problems caused by soil disturbance.

In early Mesopotamia, around 4300 BCE, a collection of city-states called the Akkadian Empire began growing and spreading throughout the area. The Akkadians were notable for their reliance on grain and wine, having major portions of their land devoted to agriculture for these crops. The Akkadians were some of the first societies to heavily practice plowing fields before planting, turning over their soil and causing massive damage to the environment below ground. They thrived for about 150 years, when their empire suddenly collapsed. Historians originally thought the collapse was due to invasion by hostile groups, however recent studies have shown a different story. We have learned that this collapse was because of a series of droughts. Strangely, these droughts didn’t come from a lack of rainfall. They were caused by the soil’s lack of water retention and erosion prevention after over a hundred harvests of plowed fields (NOAA, 2018). “The large fields produced no grain, the flooded fields produced no fish, the watered garden produced no honey and wine…” wrote one citizen in The Curse of Akkad circa 4000 BCE. While there is very little evidence so far, some people think this was also the case for the collapse of ancient Rome, as more historians are noticing higher levels of topsoil dust in marine sediment studies (Brady et al., 2019).

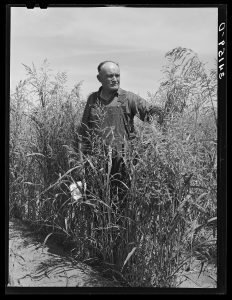

In 1935, historic agriculturalist John Deere wrote about the benefits of the plow, stating, “In general, the seed bed should be roomy, thoroughly pulverized and compact.” The goal, according to his book, was to “break up clods and crusted top soil, leaving a fine surface mulch for planting or for plant growth” (Deere, 1935). Plowing fields had started to rise in popularity in western farming around the early 20th century. As economic pressures in the 1920s pushed farmers in the Great Plains to farm on more untouched grassland, an incredible portion of the midwest was turning into farmland. Most farmers around this time plowed their fields immediately after harvest, leaving the topsoil exposed for the majority of the year. Over time, small particles in the topsoil would be picked up and eroded by the wind, often collecting into clouds of dust, eventually becoming what we know today as the Dust Bowl.

This trend of soil disturbance had been advertised as the best thing you could do for the health of your farm, yet it was slowly crippling families’ ability to survive off of the land. In the late 1930s, Congress and the Farm Security Administration began to recognize the cause of the issue. Soon, as the critically acclaimed documentary The Plow That Broke The Plains grew in popularity, the American government took action. Congress passed the Soil Conservation Act, which required changes in plowing and tilling techniques, and implementing aid to help prevent wind erosion in the future (Ganzel, 2020). Although there is a mountain of evidence and Congress’s stamp of approval, many people still believe that tilling or plowing is the best way to keep your farm healthy and efficient. We are seeing similar soil destruction happening again with the massive sale of farms all across the world as farmers struggle to produce enough crop yield on damaged soil (Montgomery, 2017).

Regenerative Agriculture

In response to these trends, a new style of farming is slowly gaining popularity around the world. Regenerative agriculture is a farming technique that attempts to bring back the original love and care of creation into farming. The advocates for this farming technique provide very simple questions for traditional farmers: why disrupt the soil and resort to chemicals when nature never has these problems in the first place? Regenerative agriculture can be achieved in multiple different ways, but the main idea is to restrict soil disturbance as much as possible. In order to do this, tilling is off limits, and to prevent weeds while keeping the soil covered, farmers plant cover crops such as legumes, which only grow a foot high, allowing taller crops like corn to thrive among them. When planting seeds, new equipment such as the John Deere 1590 work like traditional seeders, while planting seeds in tiny slices in the soil instead of harming or turning over the soil.

Some farmers, those who don’t have operations large enough to require machinery, plant their crops among woodlands, keeping the soil covered by grass, moss, and trees. With this new form of agriculture gaining speed, most farmers, while seeing less crop yield at the start, are reporting much higher and more stable level of crop production over time (Montgomery, 2017).

Throughout all of time, religion has been an important factor in farming. God’s creation has been appreciated and studied by civilizations around the world. This connection of God to agriculture has been severed in the past few centuries. Many people are trying to take advantage of God’s gift to us by trying to get around nature and make production more efficient without considering long-term issues. Humans have been trying to pack crops as tight together as possible, and when farmers run into issues with bugs or weeds, chemicals, fertilizers, and pesticides are used first and foremost. Not only have these chemicals shown to be short-term solutions, as the amount farmers need to use has risen every year for the past two decades, the chemicals can often harm nature downstream of the farm (Montgomery, 2017). In David Montgomery’s book, Growing a Revolution: Bringing Our Soil Back to Life, Montgomery interviews multiple farmers, many of which are recently making the change from traditional to regenerative agriculture. I was surprised to read about the number of farmers who are moving to regenerative agriculture for religious reasons, seeing it as something to bring them closer to God. “…many of those in the regenerative agriculture movement are Christians, seeking to be good stewards of the land they’ll someday pass on to their children and grandchildren,” one farmer says. “His faith is central to his enthusiasm about restoring his soil;” Montgomery describes another farmer’s passion for soil restoration, “It’s all about taking care of creation” (Montgomery, 2017, Ch.9). The line between God and our use of His creation may have been blurred over time, but regenerative agriculture is proving to be a lens to making it clear once again.

Conclusion

For tens of thousands of years, trends in agriculture have remained relatively stagnant. Over time, much like I had done with my own religious beliefs, humans have created a divide between science and religion. Even I had considered them to be antonyms. Agriculture slowly split from its original image of a gift from God’s creation to keep us healthy, to yet another production of food that we can exploit for short term peaks in profitability. Regenerative agriculture is proving to be a new trend in farming that brings science back to how nature grows crops as efficiently as possible for a sustainable yield. Chemicals are slowly losing their popularity with farmers, and those ‘pesky’ plants that grow in between crops are becoming an important part of farm health. As one farmer put it in Growing a Revolution, “When I was farming conventionally, I woke up and decided what I was going to kill today. Now, I wake up and decide what I’m going to help live” (Montgomery, 2017, Ch. 9). I have learned that science and religion can work together to provide the best solution for humans. No matter who you praise, your god’s creation is productive, efficient, and beautiful without human intervention. Humans are learning to utilize it instead of exploiting it. Although I still don’t consider myself to be anything more than agnostic, I understand that the natural world has grown powerful and productive after millions of years of evolution. Putting it to good use instead of destroying it has proven to be our best option.

References

Brady, N., Weil, R., & Brady, N. (2019). Elements of the nature and properties of soils (4th ed.).

Deere, J. (1935). Operation, care and repair of farm machinery (1st ed.). The Lyons Press.

Ganzel, B. (2020). Over-Plowing Contributes To The Dust Bowl Or The 1930S. [online] Livinghistoryfarm.org. Available at: <https://livinghistoryfarm.org/farminginthe30s/machines_05.html> [Accessed 6 November 2020].

Montgomery, D., (2017). Growing A Revolution: Bringing Our Soil Back To Life. 1st ed. W. W. Norton & Company.

NASA Goddard. (2014). NASA | A Year in the Life of Earth’s CO2 [Video file]. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1SgmFa0r04 [Accessed 6 November 2020]

NOAA. (2018). Drought And The Akkadian Empire | National Centers For Environmental Information (NCEI) Formerly Known As National Climatic Data Center (NCDC). [online] Ncdc.noaa.gov. Available at: <https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/abrupt-climate-change/Drought%20and%20the%20Akkadian%20Empire> [Accessed 4 November 2020].

Nrcs.usda.gov. (2020). Soil Health Management | NRCS Soils. [online] Available at: <https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/soils/health/mgnt/> [Accessed 5 November 2020].