9 The Spirituality of Art: Finding God at the End of a Paintbrush

Anna Rose

My name is Anna Rose! When I am not in school, I can be found birding, painting, sketching, playing the piano, or reading a good book somewhere on campus! My inspiration comes from the time I spent in the Wind River Basin of Wyoming and West Virginia’s Appalachia experiencing and painting the gorgeous landscapes…read more.

What did I get myself into? These were the first thoughts in my head as I squinted to get a better look at the glacier I was supposed to hike up to… almost too far away to see. With a group of other artists, I was supposed to trek up the steep side of a mountain to Lake Louise and the receding glacier behind it around 8,000 feet above sea level. Here in the Wind River Range in Central Wyoming, the nearest town was a couple hours away so there was no turning back now. We gathered our tripods, panels, brushes, and paint and hoisted our art supplies onto our backs and strapped bear spray to our fronts for easy reach. It was my first ‘advanced’ Plein Air hike, and I was about to discover just how difficult this art form was!

I was introduced to the art of Plein Air by complete serendipity. An artist friend of mine called me one day to say they had one more spot to take a two-day class with a well-known landscape painter, Wanda Mumm, in Cincinnati. With excitement, I took the spot and drove down to the city on snowy day in January, my junior year in high school, and little did I know this simple art class would change my life. That is where I learned what Plein Air painting meant. Plein Aire painting is the act of painting landscapes outside and it includes all the challenges and joys that come with being in the great outdoors! Wanda regaled us with colorful accounts of her journeys in Wyoming and Montana and I was floored by the beauty of her pieces. For our studio time, I put my heart and my soul into learning new landscape techniques, and I finished the second day with a beautiful Ohio landscape—the first landscape I had ever painted. I didn’t realize that Wanda had been watching my enthusiasm with keen interest, and she invited me to continue to learn Plein Air alongside her with a small group of talented young artists across the country.

Now, here I was, on a treacherous trail carrying haphazard boards and paints while worried a Grizzly bear might jump out and eat me. Nevertheless, we all made it up to the glacier, and I set to work on my painting… only for a swift gust of wind to blow my oil paints, art piece, and tripod all into my face. Despite some ruined clothes and a ruined painting, I had a marvelous journey. Something changed in me after staring at that lake for hours, I had spent so long quietly observing that I felt more connected to nature that I had ever been before. That is when I began to get an idea that drawing and painting nature may be a way to better understand and connect to the environment.

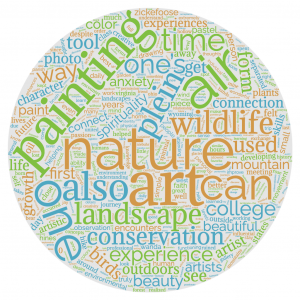

During my first semester of college, I was a decidedly lost individual. I had been raised in a devoted Roman Catholic family, and though I valued my faith, I had drifted away from the daily prayer and weekly mass that had kept me rooted throughout my childhood. The constant classwork and isolation of living in college dorms also kept me firmly separated from what I thought was ‘real’ nature. Some of the consequences of being separated from my faith and nature was a general depressive state where I felt a lack of motivation and doubt that I was heading in the right direction in life. Drawing not only became my solace during this time, but a way for me to connect back to nature by drawing plants, wildlife, and landscapes. In the last few years, I have learned that Plein Air art can be used as a tool to connect to nature as well as one’s own spirituality. In discussing how art can be used to encourage personal growth, promote a better connection to nature and wildlife conservation, and improve one’s spirituality, I will show how my artistic journey has led me on the path to becoming a more confident and mature individual.

Plein Air can be used as a tool for character growth as a person achieves development by awakening the expressive and creative parts of their being. Any wildlife or botanical artist knows that painting nature takes patience, dedication, and a deep understanding of form and detail. Plein Air artists must also keep the same tenants in mind while also braving the great outdoors. Besides painting a landscape, one is exposed to a whole array of stimuli that would not be perceived or noticed in a simple reference photo of a landscape. Whether it is standing on a rock, perching on a ledge, or nestling amongst brush; Plein Air demands that one sits among nature and builds a relationship with her. This intake of one stimulus at a time to form an art piece helps build creativity because it forces an artist to think for themselves and make decisions in color, form, and composition. No photo, no matter how beautiful or detailed, can possibly recreate the experience of using one’s own senses to study and translate a landscape onto an art board. Plein Air art also gives one full creative control of the art piece unlike a photographic reference. When I look at a landscape, I have the creative freedom to pick and choose the ‘stars of my show’ by placing trees, landscape formations, and sky features wherever I desire. The purpose of Plein Air is not to exactly copy what one sees in the landscape but to engage with nature and your own creativity to capture an art piece that not only accurately exhibits nature but your own artistic style.

Plein Air can also be used as a tool for character growth by helping one gain a deeper understanding of beauty as well as separate from a sense of self. This quote by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, a German poet born in the 18th century, is a great segue into a discussion on beauty:

A man should hear a little music, read a little poetry, and see a fine picture every day of his life, in order that worldly cares may not obliterate the sense of the beautiful which God has implanted in the human soul. (Goethe & Hutter, 1982)

There are two levels of beauty: an aesthetic sense when we see a beautiful rose or person and a higher level of beauty that is spiritual. Plein Air encourages keen observation of your surroundings allowing one to open themselves to sights like the rustling of the leaves in the trees, the way a sunset dances on the hillside, or a nest of birds in a near shrub. Recognizing nature’s intricacy in this spiritual form of beauty gradually “loosens our attachments[s] to own our desires and ideals, and as this happens, we are freed, at least for a moment, from the prison of our selfish view” (TenElshof, 2011). The ability to go outdoors and paint, even on campus, during my early college years was integral to ‘unselfing’ in a time when too much pressure on myself and my future led to significant stress and anxiety. According to David Loy in “Healing Ecology” (2010), a sense of self “is composed of mostly habitual ways of perceiving, feeling, thinking, acting, reacting, remembering, intending, and so forth.” Separating from this monotonous self is much easier in Plein Air because I simply become another observer of the landscape content to just put brush to board. Plein Air enhances my capacity to notice beauty in the small things around me in my daily life by improving my observation skills which has helped make me a more grounded and less selfish person.

I also met a wide variety of amazing people during my Plein Air adventures. Meeting folks of all different backgrounds and stories helped me discover my own identity, and these are experiences I never would have had without Plein Air. Of course, I have nothing against the dedication and experience gained by one studying art alone in their own space, but the experience of actually going to visit the landscapes or wildlife you wish to paint results in unparalleled encounters. Along the way, there is also no avoiding meeting all cultures and flavors of people in these beautiful spaces. As a formerly timid, young woman, positive meetings such as these really shaped my confidence. Some of my most memorable experiences are from the time I stayed in Dubois, Wyoming, which is a tiny town with a rich history in cowboys. In exchange for a slice of pie at the local diner, I would hear hours’ worth of stories from these men and women dressed in cattleman hats and bolo ties. We discussed things I had only read about in college, like conflicts between ranching; reservations; and the federal government, but now I was able to place faces behind concepts I was learning as an environmental science student. While on the search for a few rare plants I wanted to find, a woman from the Eastern Shoshone tribe helped navigate me through the Wind River area of Central Wyoming. Her profound connection to nature and intimate knowledge of the landscape helped encourage me to continue my journey of learning about ecosystems through my art.

I also met a variety of influential people for my personal growth during the summers I spent wandering the wilder parts of West Virginia. One of my best friends who had grown up exploring the state was my guide for many of my painting adventures there. Despite being a similar age something about him seemed older, more worn, and wise beyond his years. In the places he knew he would spend hours telling me the history and story of the mountain as well as any forest, tree, or log within its domain. Many of the artistic choices I made during the trip were because of the observational skills I learned from him. Such powers of observation in the environment around me have made me more aware of the emotions of others and in myself too. A few towns over in Thomas, West Virginia, I visited an art gallery this summer run by a husband and wife, named Marty and Delia, out of their home. The downstairs walls were covered in magnificent prints of birds, plants, mountains, and other nature scenes. Once they discovered I was a fellow artist, they invited me to stay in their home in exchange for a few days of work in their garden. I happily accepted. I got to spend a portion of my summer working in their vegetable garden, helping run the gallery, and setting out to Plein Air paint in Dolly Sods and other parts of Canaan valley in the afternoon. Delia and I would spend our mornings together sketching the garden plants as she gave me words of advice on developing as a professional artist. In this small mountain town, everyone knew one another, and I had soon established a relationship with several of the locals. For the first time in my college years, I had the chance to truly slow down and devote my time to art and learn about myself. My time with Delia and Marty allowed me to finally begin seeing myself as a professional artist—a big step in my identity.

Plein Air is also a wonderful tool that allows one to extend their senses beyond normal functioning though an in-depth study of form, movement, detail, and color theory. As human beings, we have the incredibility ability to see an endless number of shades of color due to the cones in our eyes. In comparison to most other mammals, we also have extremely acute eyesight when it comes to movement as we can cue into objects moving even at the corners of our vision. However, despite our strengths in color and movement perception, humans are surprisingly bad at distinguishing light sources and noticing fine details. Artists must continually fight the urge to gloss over details in their artwork where attention to the small pieces is what makes or breaks a superb and accurate art piece.

A famous author, artist, wildlife rehabilitator, and personal friend of mine, Julie Zickefoose, often speaks on her close encounters with injured and orphaned wildlife she rescues. In her book, Saving Jemima, Zickefoose not only forms a close relationship with a Blue Jay, but she paints the jay on a daily basis and remarks how her perspective on the form and color of birds has completely changed after spending such a significant amount of time raising them (Zickefoose, 2019). Even with birds Zickefoose watches in the wild, she notices behaviors and feather details she would have never picked up on without careful sketches and watercolors of the birds in her care. In a similar way, the more I paint landscapes the more colors and shapes I perceive as the scene reveals its personality to me. It takes time to train the eye and mind to see ‘more,’ but painting is a wonderful way to build one’s observational skills. There is often an A-hah!moment in new artists when they finally learn to mentally break down the essence of a scene before them. One of my favorite moments with my friend from West Virginia was the moment he realized, “WOW, I can see those colors, Anna! The mountains are purple!”

Plein Air can also be used as a tool for wildlife conservation and help people build a better connection to nature through its ability to tell a story in media everyone can understand. My favorite example of art in conservation is of Bob Hines who was one of the most influential artists and conservationists of the 20th century in the United States. In 1912, Hines was born in Columbus, Ohio and had a long career working in Ohio for the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). One of his best works was Birds in Our Lives which combined both writing an Hine’s beautiful artwork to tell in a “simple, objective, and comprehensive way, about the uses, problems, needs, and present status of birds in the United States, so that Americans in all walks of life will be informed about them” (Juriga, 2012). It was the art in this high-profile piece published in 1966 that allowed for its wide appeal and the pieces’ ability to be relatable to all. Hines also greatly contributed to conservation through his work with the wildlife conservation stamp as well as the duck stamp. Obviously, art on paper is not the only way that environmental education can be conducted as poets, writers, musicians, and sculptors can all contribute to the discussion of conservation. Art can be used as a tool for educating others on wildlife conservation when it presents nature in a way that is accessible to the general public and aesthetically pleasing.

Painting outdoors can also create the opportunity for a physical encounter with nature which is also essential for developing a relationship with the environment. There are all sorts of encounters—positive and negative—that come along with Plein Air painting! Bugs. Sunburns. Meeting new people. Wildlife encounters. Storms. Sunlight. The point is you have to be outside and immersed in nature to have the most meaningful experience. In the book, Lost Connections (2018), by Johann Hari, the renowned bonobo expert, Isabel Behncke, insists that Hari make the trip with her up the side of the mountain in order to ‘get his hands dirty’ and truly experience what he intends to write about in his novel. Hari writes in his novel about the health crisis that is the ever-increasing levels of depression and anxiety in our society. He identifies a lack of the natural world in our lives as a key reason for the increase of feelings of isolation and loneliness in humans. Behncke goes on in the interview (as they hike up the mountain) to discuss how feeling apathetic and alone as a result of a loss of a connection to nature can actually be a great motivator for reconnection. I find these thoughts similar to my own experience of reconnecting to nature in my college years. The loneliness I felt in being perched up in a dorm room and a lack of time to go outside gave me the drive to dive into my passion for Plein Air painting. While Plein Air is an inherently involved experience, painting wildlife or landscapes in the shelter of one’s own home is a much more passive and insulating one. The activity of painting outdoors gives the “presence of something capable of engaging, rather than merely occupying, the individual—a stimulus for intensity of experience, for the full involvement of the senses and the mind” (Sax, 1980). Physical encounters are necessary for truly connecting with nature, and Plein Air is one of many great ways to get your hands covered in dirt (or paint)!

More reasoning for why a physical encounter with nature through art may be necessary for one’s psyche is that exposure to the outdoors is essential for cognitive development. In the United States alone, more than “half of the population lives in suburbs and an additional 30% live in urban centers” (Miller, 2005) meaning our society is becoming increasingly separated from nature. According to the journal article, “Biodiversity conservation and the extinction of experience,” it is thought that “physical… contact with nature [promotes] high-order cognitive functioning, enhances observational skills, and the ability to reason” (Miller, 2005). For adults and children alike, exploring nature through the lens of art (which is both fun and an expression of creativity) could help alleviate the widening chasm between our society and the environment. A concept that may explain why humans have this ‘need’ for nature is the biophilia hypothesis—humans are engrained with the innate drive to seek connection with nature and other species besides themselves. Evidence shows that exposure to natural systems helps improve recovery from stress, recuperation from traumatic events, and improve well-being (Miller, 2005). Since Plein Air is an avenue in which one can make contact with nature, it can be viewed as an activity that not only engages and improves one’s mind and character, but also one’s soul.

Now that Plein Air has been discussed as an outlet for personal growth and conservation, it can finally be viewed as a tool to connect to one’s spirituality through nature. My experiences with art in nature has also been integral for my acceptance of myself as a spiritual person and has helped me rebuild my faith in Catholicism. Ever since I was a baby, my parents have taught my sister and I to grow up as moral, thoughtful, and spiritual humans. This was predominately through our Catholic parish by going to church school several times a week, attending mass, helping out in youth group, and my parents giving us faithful words of advice. My religion was extremely important to me growing up because it was the model I consulted to know how to treat others, myself, and the lens that I viewed the world through. College changed this for a few years. The isolation I felt from my home, my support system, and my parish made attending church feel more like an inconvenience than a safe place. At the same time, my growing anxiety over my own future as well as the future of our planet due to climate change was mounting as I buried myself in schoolwork.

In continuing my faith and spirituality journey, I would soon learn that connecting to nature through my artistic journeys was an effective tool for me to combat the anxiety I had been developing during my first few years of college. Reinhold Niebuhr is a prominent Protestant theologian of the 20th century, and as an anxious student, I found his work on anxiety and the human condition to hit a little too close to home. A definite low point in my faith journey occurred during my first few semesters of college as I attempted to “deny the limited character of [my] knowledge, and the finiteness of [my] perspective” (Niebuhr, 1941). In my attempts to get perfect grades, work long hours on the weekend, get the best internship, and never take breaks I was barely conscious of the damage I was putting my body, mind, and especially my faith through. As Niebuhr (1941) hints, I was so afraid of the limits of my own passion that I fell into the temptation of perfectionism at the cost of relationships, hobbies, and my own happiness. Falling back on my passion for art was a godsend in this particular instance because it allowed me to remember my love for the world. My love for form, shape, texture, color, and well, the creator of all those things: God. Plein Air, whether it is in a garden, forest, or mountain range, quiets one’s anxiety and prepares them to connect to nature in a spiritual way if they desire.

Through the explanation of how Plein Air art can improve one’s personal and character growth, promote wildlife conservation and a better connection to nature, and an improved understanding of one’s spirituality, one can see that art in nature can offer anyone satisfying and enriching life experiences. In the last few years, my skill for art and my own personality have developed in tandem resulting in someone that is more confident in her identity and in her future. A culmination of my experiences honestly occurred in my ENR 3470: Religious and Environmental Values in America class with Dr. Greg Hitzhusen. I learned many of the concepts that I had no name for and gained a better understanding of spirituality in many forms. I was touched when a fellow student, Erica Hu, asked to go out Plein Aire painting with me. One of the questions she asked struck a chord in me—How do you stay passionate for your art all the time? This is when I realized that without the nature component of Plein Air, I would not be inspired to follow my passion for art. The truth is that my passion for illustration and painting is a constant struggle for motivation and free time. Yet, when I’m Plein Air painting my worries melt away. It becomes just me, my paintbrush, the wind in the trees, and God. —

Visit my artist website and blog at annarosepaints.com

References

Goethe, J. W., & Hutter, C. (1982). The sorrows of young Werther: And selected writings. New American Library.

Hari, J. (2018). Lost Connections. Bloomsbury. https://thelostconnections.com/the-interviews/interviews-page-four/

Juriga, J. D. (2012). Bob Hines: National wildlife artist. Beaver’s Pond Press.

Loy, D. R. (2010). Healing ecology. Volume Journal of Buddhist Ethics (pp. 254-267). Retrieved from http://www.buddhistethics.org/

Miller, J. R. (2005). Biodiversity Conservation and the extinction of experience. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 20(8), 430–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.013

Niebuhr, R. (1941). Man as Sinner. The nature and destiny of man: A Christian interpretation. (pp. 178-207) New York, NY. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Pollan, M. (2003). Second Nature. Grove Press.

Sax, J. L. (1980). Mountains without handrails: Reflections on the national parks. University of Michigan Press.

TenElshof, J. (2011, March 17). What makes a beautiful soul? The Good Book Blog – Biola University Blogs. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.biola.edu/blogs/good-book-blog/2011/what-makes-a-beautiful-soul.

Zickefoose, J. (2019). Saving Jemima. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.