Human-Wildlife Conflict

2.4 Human-Coyote (Canis latrans) Interaction and Conflict

Ashley A. Neal

The adaptability of coyotes to expanding urban landscapes has brought about much concern over the potential consequences of human-coyote conflict. What is causing the urbanization of the species? What management procedures should be in place to prevent attacks?

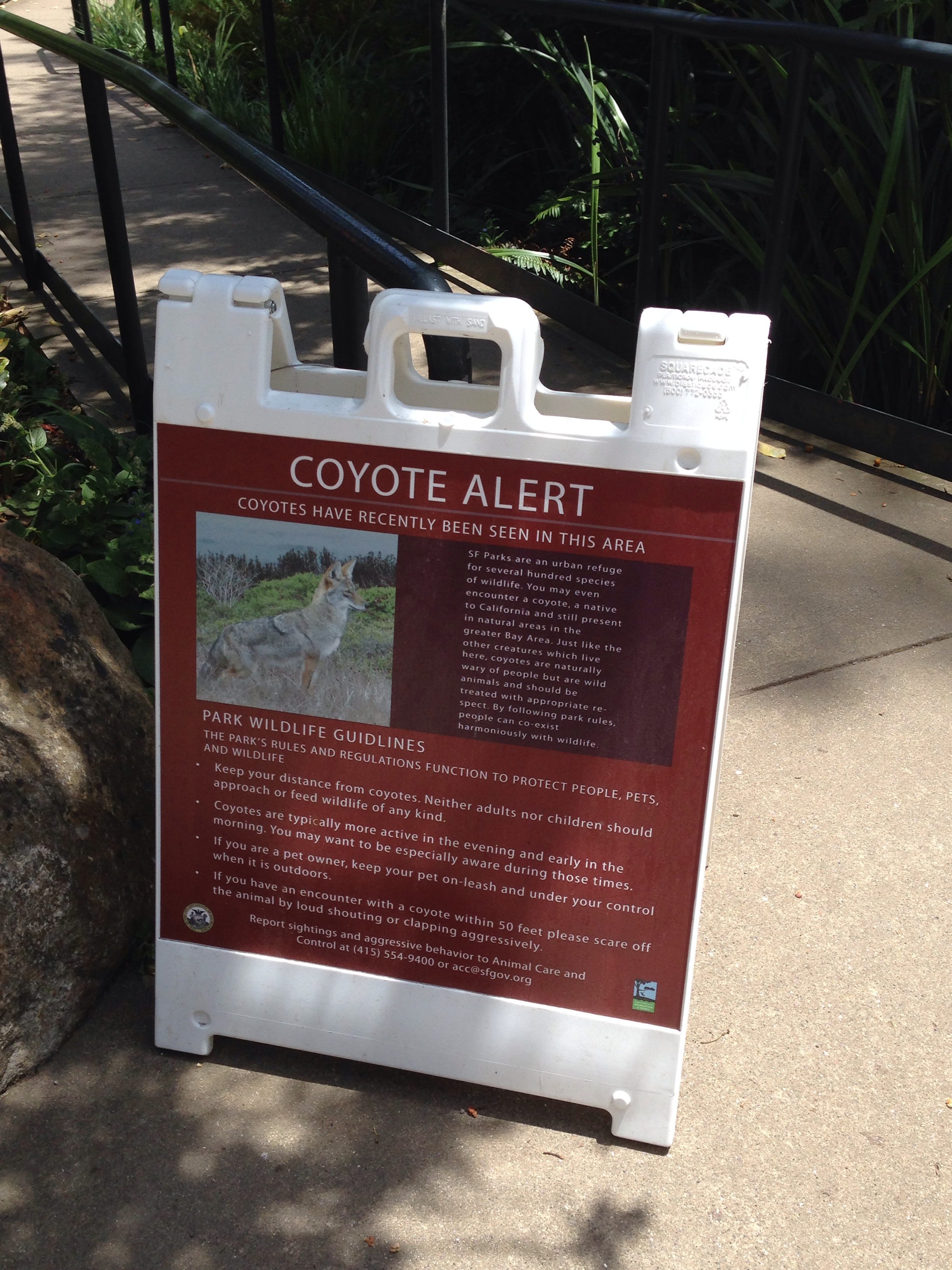

Coyotes are among the animal species most equipped for adaption in response to human presence.5 Gravitating more frequently to suburban and urban areas, sightings of coyotes have increased recently as well as concern over their close proximity to human populations.1,2,3,4,10 Through adaption to their surroundings, such as avoiding heavily populated areas, using land cover for protection, and adjusting their diet to include human-provided nutrition and other smaller domesticated animals, coyotes have successfully adjusted to human urbanization.4,9 Because of this, the number of human-coyote conflicts has risen.2,3,10 Surveys conducted have highlighted the correlation between a lack of education of coyotes and a high level of apprehension about them, indicating a need for more focused educational awareness in areas where coyote populations are common.2

A general trend of coyote avoidance of humans was found by Gehrt, et al. (2009), who studied the activity of coyotes in urban areas.3 Their study of radio collared coyotes showed that although they used urban land for traveling purposes, they did so nocturnally and in areas with low human activity.3 Ditchkoff, et al. (2006) explored the issue of behavioral changes in animals that acclimate to living in urban areas.1 Along with modifying their activity to twilight or night hours, their diet shifted to more human-provided food, such as trash dumps and roadkill.1 Reproductive adaption of coyotes in response to urban living is another important factor to consider.1,3 Changes in diet, home range size, and urban noise can all adversely affect the reproductive patterns of coyotes in terms of the success of breeding, the likelihood of finding a suitable mate, and raising offspring.1

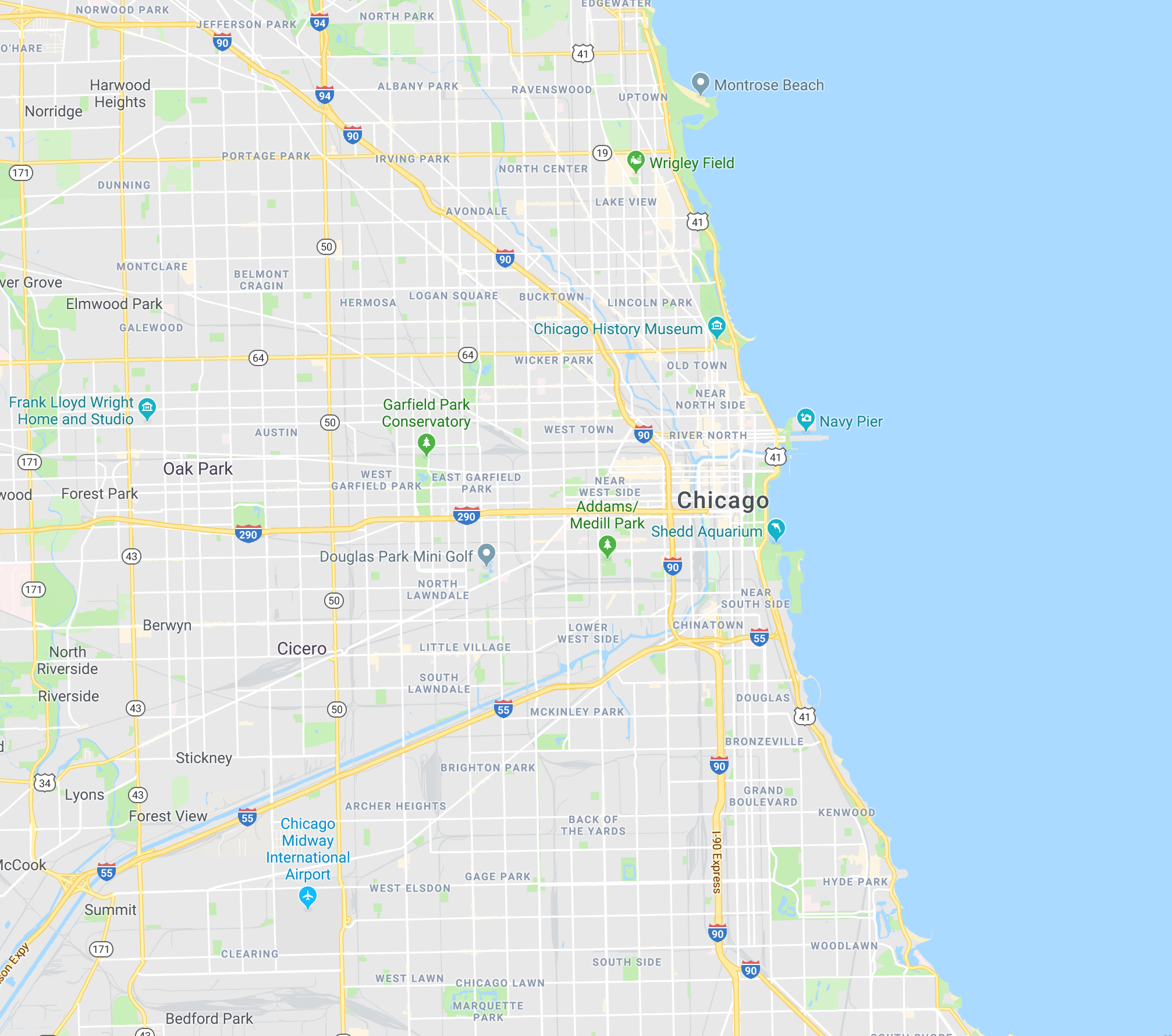

Chicago is one city in which coyotes have pervaded the urban center and established their residence.3,4,6,10 Gese, et al. (2012) studied the space use of coyotes in urban Chicago and their use of different levels of developed areas (Figure 2).4 Using radio collars on the coyotes over the course of two years, they found that most coyotes inhabited the less developed areas due to the increased availability of prey and resources, and to avoid humans.4 Coyotes in developed areas had home ranges twice the size of coyotes in less developed areas, suggesting that they need to cover more space to account for the lower density of prey and necessary resources.4 These coyotes had home ranges stretching to less developed areas, which supports this notion.4 The researchers found no differences in the use of urban land between day and night for coyotes, suggesting either human activity constrained coyote activity to strictly nocturnal hours, or coyotes used urban land regardless of the temporal patterns of human activity.4 Their use of urban land was restricted to only traveling on paths to less developed areas, showing a deliberate intent to avoid humans.4,5,9

More recently, Magel, et al. (2014) used motion-triggered cameras to study coyote distribution and patch occupancy in Chicago’s urban center (Figure 3).6 They found that coyotes select habitat patches based most strongly on canopy cover.6 Human and pet visitation of the camera sites was found to be negatively connected to patch occupancy and colonization of coyotes, although there was a positive relationship between coyote patch occupancy and the distance to Chicago’s urban center.6 The researchers also found a negative correlation between the housing density and amount of roads of a particular site to colonization that of that site by coyotes.6 Their results suggest coyotes go to high density areas, such as the urban center, but avoid areas with high human activity, like industrial sites or cemeteries.6 Their results align with Gese et. al. (2012) in that coyote use of urban land depends heavily on the avoidance of humans and the availability of land cover and resources.4,6

One important contributor to the species’ population increase was the reduction of wolf populations across the country. Replacing the wolf as the apex predator in many ecosystems, and by becoming more of a mesocarnivore, coyotes have demonstrated their ability to pervade and thrive within urban human boundaries.7 Despite this, many challenges still exist on how to handle the increasing human-coyote conflicts and to develop new wildlife management procedures to decrease the risk involved with human-wildlife interactions.10 One of the most significant risks of the increased interaction between coyotes and humans is the potential for harmful attacks.10 White and Gehrt (2009) analyzed reports of coyote attacks on humans in the United States and Canada and found that the greatest proportion of attacks were either predatory or investigative.10 Children made up the greater part of victims and interestingly, children were the victims of predatory attacks significantly more often than non-predatory attacks.10 This could be a result of various factors, including their smaller size, or it may be due to a child’s lack of appropriate awareness of the danger of wild animals as compared to an adult’s.10 One of the most noteworthy findings of this study was that of all the reports analyzed, 30% involved an accidental or intentional feeding of the coyote by a human preceding the attack.10

Many methods have been implemented all over the world to handle conflicts with carnivores such as coyotes. These include eradication, harvesting, and prevention.8 Although eradication and harvesting, which is systematic hunting of the problematic species, were effective in decreasing the population of the species, they created imbalance in the local ecosystems by removing key predators needed to manage the populations of other animals.8 While many species were saved from extinction, the costs of doing so were high.8 This includes the expenses of managing these populations and dealing with problematic individuals using non-lethal methods such as translocation.8

To minimize the risk involved with the increased interaction between humans and coyotes without jeopardizing the wellbeing of the species, education and awareness about wild animals and actions to take in an encounter with them is necessary. Previous methods of managing the growing population of coyotes, especially in urban Chicago, have had both positive and negative consequences. Further research is needed to find a solution to these human-coyote conflicts.

References:

- Ditchkoff, S. et al. (2006). Animal behavior in urban ecosystems: Modifications due to human-induced stress. Urban Ecosystems, 9(1):5-12.

- Draheim, M. M., et al. (2013). Attitudes of college undergraduates towards coyotes (canis latrans) in an urban landscape: Management and public outreach implications. Animals, 3(1): 1-18.

- Gehrt, S., et al. (2009). Home range and landscape use of coyotes in a metropolitan landscape: Conflict or coexistence? Journal of Mammalogy, 90(5):1045-1057.

- Gese, E., et al. (2012). Influence of the urban matrix on space use of coyotes in the Chicago metropolitan area. Journal Of Ethology, 30(3):413-425.

- Gilbert-Norton, L., et al. (2009). Coyotes (Canis latrans) and the matching law (English). Behavioural Processes, 82(2):178-183.

- Magle, S., et al. (2014). Urban predator–prey association: coyote and deer distributions in the Chicago metropolitan area. Urban Ecosystems, 17:875-891.

- Meachen, J. A., et al. (2014). Ecological changes in coyotes (Canis latrans) in response to the ice age megafaunal extinctions. Plos ONE, 9(12):1-15.

- Treves, A., & Karanth, K. (2003). Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conservation Biology, 17(6):1491-1499.

- Waser, N. M., et al. (2014). Coyotes, deer, and wildflowers: diverse evidence points to a trophic cascade. Die Naturwissenschaften, 101(5):427-436.

- White, L., & Gehrt, S. (2009). Coyote attacks on humans in the United States and Canada. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 14(6):419-432.

Figures:

- Google Maps. [Map of Chicago]. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/maps/@41.7756824,-88.0032109,10z. Public Domain.

- Picken, John. (2011). [Photograph of Coyote in Lincoln Park near Belmont Harbor, Chicago, IL]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 2.0.

- sandid. (2017). [Photograph of wildlife trail cam]. Retrieved from Pixabay. Public Domain.

- skeeze. (2008). [Photograph of coyote along roadside]. Retrieved from Pixabay. Public Domain.

- Walling, Steve. (2014). [Photograph of Coyote alert sign]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.