Sustainability

5.1 Japan’s Environmental Challenges and Energy Future

Christopher T. Hauer

Can Japan continue to thrive as an import-focused nation and what are the prospects like for nuclear power in the country? What alternatives have the Japanese government and its citizens proposed? What are the geopolitical implications of Japan’s energy future?

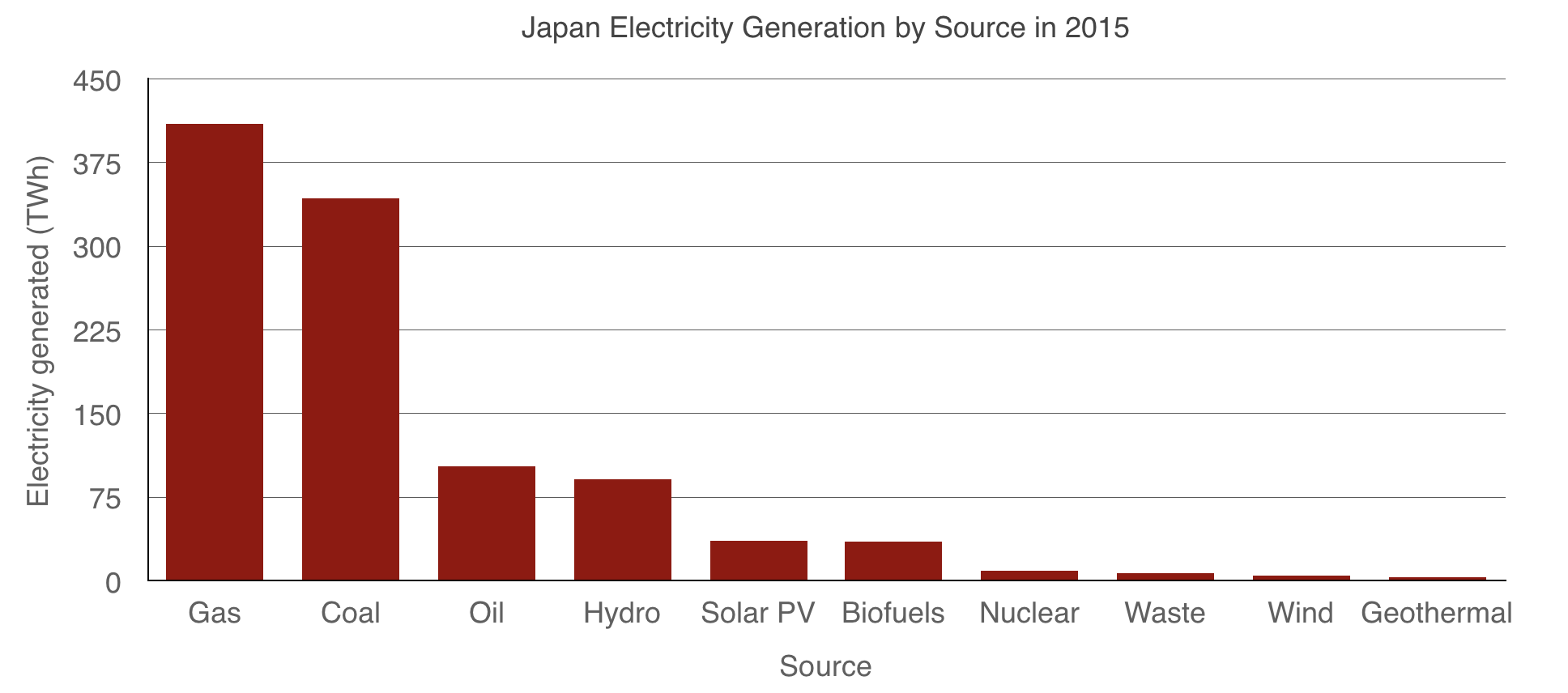

Japan has emerged from the tumult of the mid-20th century as one of the world’s leading economic and cultural powerhouses. Japan does not currently have access to any significant fossil fuel source, so they must import most of their oil from other countries.2,3 Japan’s crude oil imports have recently decreased,4 but this does not necessarily signal a shift away from imports, rather, the country’s declining population size and overall lower energy consumption appear to serve as better explanations for this phenomenon.2,4 Nuclear power has been considered an alternative solution to relying on energy imports, but there is significant concern over the safety of this option after the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.2,3 The Japanese government faces the difficult task of reconciling public opinion towards nuclear energy with the reality of being a country that relies heavily on imports.2,3,9 Research into alternative methods of energy production has increased, as has the significance of environmental policy implementation in Japan.

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster has understandably swayed public perception away from the use nuclear power.2,3 The Fukushima disaster was caused by a magnitude 9.0 earthquake, and subsequent tsunami off the coast of Honshu Island.2 This led to the full meltdown of three nuclear reactors, the loss of 17.3% of Japan’s total electricity capacity, and around 20,000 dead or missing.2 Nuclear power in Japan must be considered in the context of a country attempting to break away from its dependency on other nations for its energy. Immense import expenditures also hurt its economy.3 Statistically, nuclear power is safer than other means of electricity generation,3 and it may be in Japan’s best interests to continue investing in nuclear power. Despite currently having only two operational reactors, the Japanese government indicates that it will shift focus away from nuclear power and concentrate on coal and liquid natural gas (LNG).1,2,9 Scaling back nuclear power without fully abandoning it and focusing on domestic energy production seems to be a healthy and likely compromise.

Figure 2. Diagram of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant accidents. The Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant disaster occurred as a result of a magnitude 9.0 earthquake. This resulted in the full meltdown of three nuclear reactors. Click on each icon near the reactor numbers to read the damages sustained to each reactor.

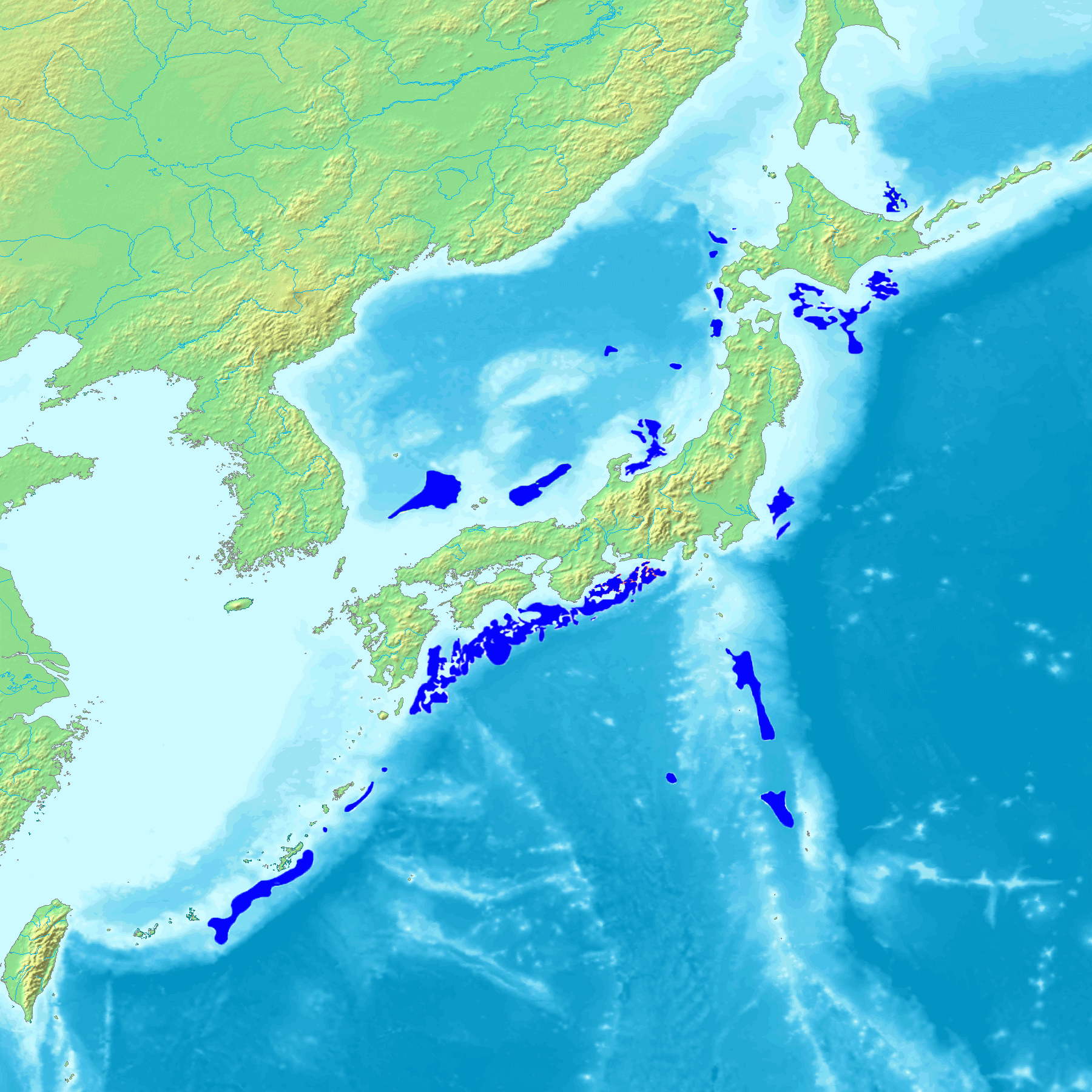

Methane hydrate reserves located around the Nankai Trough present a unique opportunity for Japan to foster commercial interest in a legitimate domestic energy source.10 These reserves were first extracted in 2013 underneath the Nankai Trough seabed, and Japan has already invested hundreds of millions of dollars into studying these reserves.10 The relationship between methane, a greenhouse gas, and anthropogenic climate change is worth investigating in this context. Gas hydrate reserves contain comparatively less carbon than fossil fuels such as coal, which is important when considering humanity’s desire to lower carbon emissions.10 The progression from high-carbon to low-carbon sources of energy favors the combustible ice reserves located in the Nankai Trough because methane is a hydrocarbon with the lowest carbon intensity.7 Research shows that even one-thousandth of the world’s supply of methane hydrate would satisfy the global energy demand for one year.1 The total gas reserves off the coast of Japan are equivalent to 40-63 times the nation’s natural gas consumption in 2012.1 There are risks, however, in that gas hydrates located underwater produce immense pressure when released, which could cause damage to the underwater environment. Specifically, the Nankai Trough is susceptible to earthquakes, due to its location near the intersection of the Philippine and Eurasian Sea Plates.6 The main goal of Japanese research and development of the methane hydrate program is to achieve commercial production by 2018, while continuing to evaluate the environmental impact and potential risks of such a venture.10

Japan has historically had a complicated history with environmental policy, both domestically and internationally. In adherence with the Kyoto Protocol, Japan has implemented national policies that have placed a greater focus on combating climate change, but their greenhouse gas emissions continue to be an issue.8 Prefectural local governments have become increasingly active in instituting policies that address environmental issues.8 While subnational governments in Japan are becoming more attentive to climate change, it has not translated to success in stimulating non-governmental organizations and individual citizens into making concerted efforts to decrease their emissions.8 Environmental and energy policies in Japan will require synergy between all levels of government and society, and will necessitate both government subsidies and civilian investment to achieve tangible results.8 The Japanese government has historically stepped in to address domestic health issues and promote environmentally conscious solutions with mixed results. The Act on the Promotion of Effective Utilization of Resources was amended in 2001 in an effort to reduce waste produced by electronic equipment such as personal computers and LCD screens.11 The domestic disposal rate was reduced, but Japan began exporting more electronic waste to other developing countries.11

Japan is effective at addressing problems, but they have not had the same success when it comes to preventing problems. The proportion of lung cancer in Japan has slowly been increasing since 1993, but deaths caused by lung cancer have decreased since 1996.5 This is a trend with other types of cancer in the country, where there is a noticeable increase in incidence and decrease in mortality.5 Although the decrease in mortality is laudable and can be attributed to improved detection and treatment, the increase in incidence can be attributed to a failure to properly address risk factors that lead to cancer.5 The Japanese government instituted the Basic Plan to Promote Cancer Control Programs in 2007, but it has not had a statistically significant impact on the decrease in incidence rates.5 The same can be said of their approach to environmental policy, which is why it will be important for the country to take more preventative steps so that they are as prepared as possible for any future challenges.

References:

- BP. (2013). BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2013. Retrieved from: http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2013/ph240/lim1/docs/bpreview.pdf

- Hayashi, M. & Hughes, L. (2013). The policy responses to the Fukushima nuclear accident and their effect on Japanese energy security. Energy Policy, 59:86-101.

- Hong, S., et al. (2013). Evaluating options for the future energy mix of Japan after the Fukushima nuclear crisis. Energy Policy, 56:418-424.

- Inajima, T., et al. (2016, January 24). Japan oil imports fall to lowest since 1988 as demand drops. Bloomberg, Retrieved from https://sg.finance.yahoo.com/news/japan-oil-imports-plunge-lowest-014300764.html

- Katanoda, K., et al. (2013). An updated report of the trends in cancer incidence and mortality in Japan. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 43(5):492-507.

- Koronowski, R. (2013, July 29). “Fire Ice”: Buried Under The Sea Floor, This New Fossil Fuel Source Could Be Disastrous For The Planet. Think Progress. Retrieved from: https://thinkprogress.org/fire-ice-buried-under-the-sea-floor-this-new-fossil-fuel-source-could-be-disastrous-for-the-planet-fdb80720e035/

- Nakićenović, N. (2002). Methane as an energy source for the 21st century. International Journal of Energy Technology and Policy. 1(2):91-107

- Puppim de Oliveira, J.A., (2009). The implementation of climate change related policies at the subnational level: An analysis of three countries. Habitat International, 33(3):253-259.

- Sheldrick, A. (2016, May 26). Japan to cut emphasis on nuclear in next energy plan: sources. Reuters, Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/us-japan-nuclear-idUSKCN0YI06Z

- Tabuchi, H. (2013 March 12). An energy coup for Japan: ‘Flammable Ice. The New York Times, B1. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/13/business/global/japan-says-it-is-first-to-tap-methane-hydrate-deposit.html

- Yoshida, A., et al. (2009). Material flow analysis of used personal computers in Japan. Waste Management, 29(5):1602-1614.

Figures:

- International Energy Agency. (2015). [Data for Japan energy consumption in 2015].

- Jakounezumi. (2016). [Map of methane hydrate around Japan islands]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 3.0.

- Sodacan. (2011). [Diagram of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant accidents]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 3.0.

- Takuo, Kawamoto. (1999). [Photograph of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 2.0.