Climate Change

4.1 Unceasing Concern for the Rapid Retreat of Mount Kilimanjaro’s White Peak

Julie E. Kemerer

The glaciers on Mount Kilimanjaro have shown a considerable decrease in area that has scientists hypothesizing about when — rather than if — the mountains’s white peak will completely disappear. With this glacial retreat, just how far-reaching will the consequences be? How much longer will these white peaks be visible?

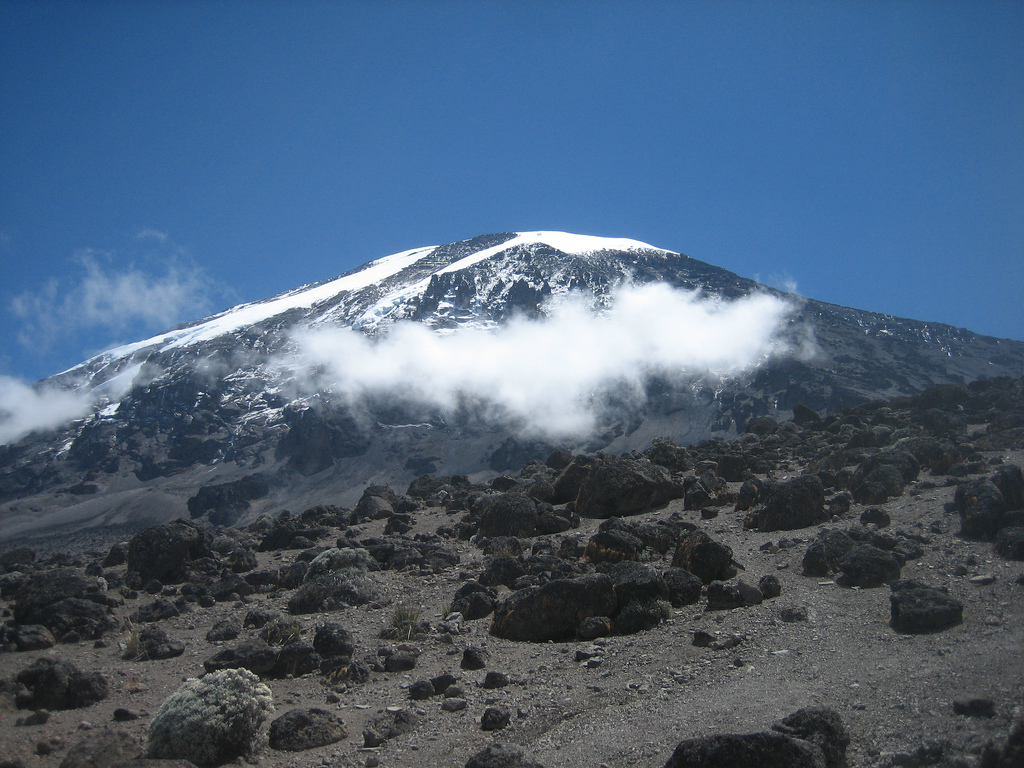

Mount Kilimanjaro, a dormant volcano in Tanzania on the border of Kenya, has been a topic of interest for scientists for over 100 years.3 Kilimanjaro is located just 300 km (186 miles) south of the equator which has caused the snow cover on the mountain to be regarded as a peculiarity.3 Ernest Hemingway, the American novelist, once described the ice fields as being “as wide as all the world, great, high, and unbelievably white in the sun”.5 However, according to scientists, these incredible ice fields are nearing the end. Now, the question is not if the glaciers will disappear, but when.

In 1912, the area of snow cover on Mount Kilimanjaro was around 11.40 km2 (4.40 miles2).2 In 2011, the area of snow cover decreased to approximately 1.76 km2 (0.70 miles2).2 This indicates that in the last century, the total loss in ice cover was around 85%.2 Furthermore, the amount of ice present in 2007 showed a decrease of 26% when compared to the measurements taken in 2000.8 There are many factors that contribute to this phenomenon. Scientists have linked global climate change to changes in greenhouse gases as well as land cover change.5 Multi-scale modeling has shown that there has been significant decrease in montane forests as well as in cloud forests.6 Research has also indicated an increase in sublimation, and a decrease in precipitation/snowfall and air humidity.4,6,8,10 Moreover, annual precipitation on Mount Kilimanjaro has decreased by 600-1200 millimeters (24-47 inches) over the last 120 years.3,9 This has led to not only the retreat of the mountain’s glaciers, but also to more frequent and intense forest fires.3,4 In the last 80 years, the mountain has lost nearly a third of its forests, which exacerbates the problem of the disappearing glaciers.3 With forest reduction, there is less moisture in the atmosphere, which leads to less cloud cover and reduced precipitation. Increasing insolation leads to more evaporation and melting.5,10 Clearly, both deforestation and the disappearance of the glaciers are detrimental to the Kilimanjaro ecosystem.3

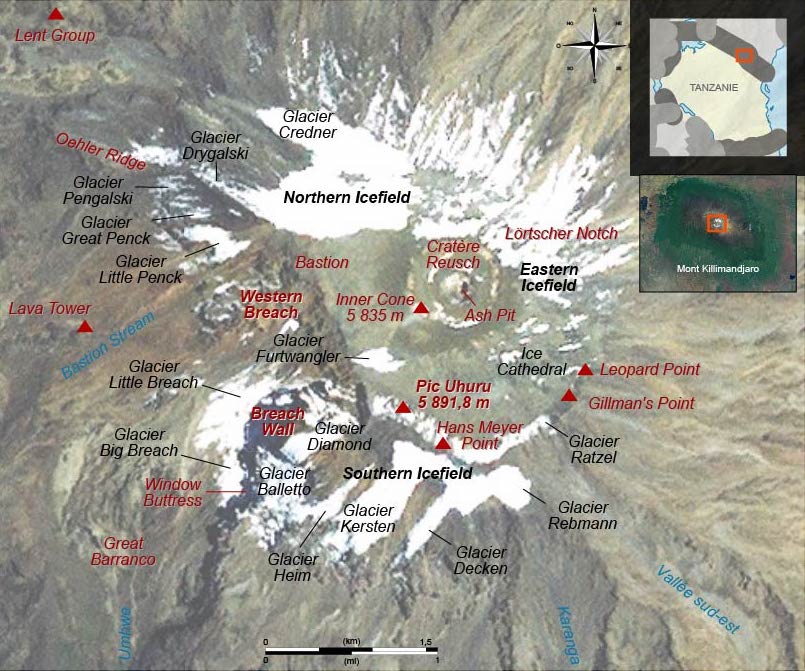

There are three remaining ice fields on the plateau and slopes of Kilimanjaro, all of which are shrinking.2 These ice fields are known as the Northern Ice Field (NIF), Southern Ice Field (SIF), and Furtwangler Glacier (FWG).2,4,10 From 2000 to 2007 all have experienced significant thinning.10 One measurement on the FWG showed that the surface lowered by almost 5 meters (16 feet) from 2000 to 2009. This ice field has already split due to such shrinkage. The effects on the SIF are not as extreme, but the ice has continued to diminish. The NIF is expected to shrink enough that it will split in half within the next few years.10 Numerous aerial photographs clearly outline the changes that the mountain has experienced since 1912 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kilimanjaro’s Disappearing Glaciers. Summit cover in 1) 1938, 2) 1993, and 3) 2000. Courtesy of Mary Meader, 1938, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0., and NOAA, 2006, Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

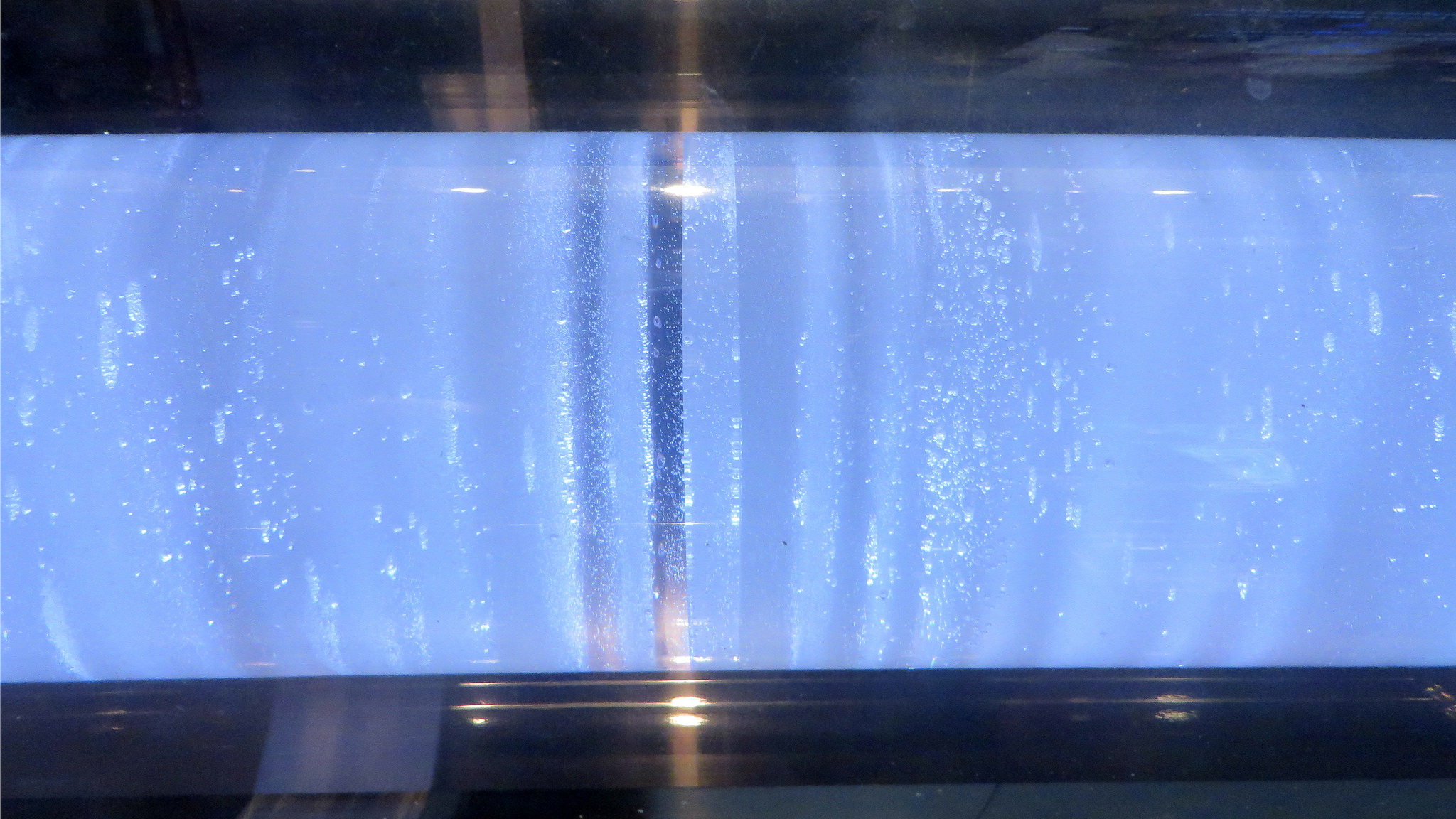

The precise measurements taken over the years have been possible through the use of numerous technologies. Global Positioning System (GPS), Automatic Weather Stations (AWS), aerial photos, and ice cores have been widely used to create maps and models.4,6,9,10 Stereoscopic aerial photo coverages have been created and then compared to demonstrate ice thinning.9 Between the years 1962 and 2000, the photos were able to demonstrate an average surface lowering of approximately 17 meters (56 feet) and thinning of about half a meter (1.6 feet) per year.9 The drilling of ice cores into the glaciers provides a clear record of 11,700 years of Holocene climate conditions.9 The first ice-core based climate history for Africa used a number of ice cores and drilled some of the longest (close to around 50 meters/164 feet deep) in the NIF, which has the largest of the ice bodies.9 Eventually, these samples showed that there was an annual retreat of roughly 0.9 meters (3 feet) compared to readings taken in the early 2000’s.9 Interestingly, the ice cores showed that the NIF persisted through an intense drought that lasted nearly 300 years, yet the ice field will most likely disappear by the year 2060, indicating that today’s conditions must be far worse than any that existed in the past 11 millennia.2

Glaciers preserve extremely reliable records of history due to the ability of ice to freeze and keep intact many attributes of the surrounding environment. Such attributes include the air temperature, precipitation, atmospheric chemistry, and volcanic depositions.11 Additionally, the glaciers preserve human activities, granting anthropologists insight into the past. Thus, with the melting of glaciers, over 11,000 years of history is being erased.11 The glacial melting also raises concern for drinking water supply, sea level rise, crop irrigation, hydroelectric production, and tourism.11 A 2001 BBC article highlighted that Kilimanjaro is the primary foreign-currency earner for the Tanzanian government.1 The article stated that “twenty thousand tourists go there every year because one of the attractions is to see ice at three degrees south of the equator.”1 The melting of the glacier may cause the Tanzanian government to earn less money from a potential reduction in tourism to the region.

The most recent reports of Mount Kilimanjaro’s glacial retreat have used linear extrapolation for all three zones (NIF, SIF, and FWG) to unfortunately conclude that the ice cover on the western side of the mountain could vanish before 2020 while the remaining ice will disappear closer to 2040.2,8 At the very latest, the ice will take until 2060 to completely disappear.2 These predictions only hold true if present-day conditions persist. Scientists are largely in agreement that ice cores must be drilled in a number of locations before the ice melts. More extreme options to prevent ice melt include the use of tarps to protect against solar radiation.7 Euan Nisbet, a Zimbabwean greenhouse gas specialist from the University of London, suggested draping the ice cliffs in white polypropylene fabric as a temporary fix.7 This would keep the ice beneath the fabric cool while research is conducted to find ways to develop reforestation plans. While none of these solutions will be a simple task, they demonstrate the efforts of people all over the world to preserve the historic ice fields of Mount Kilimanjaro.

References:

-

- Amos, J. (2001, February 19). Kilimanjaro’s white peak to disappear. BBC News. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/in_depth/sci_tech/2001/san_francisco/1177879.stm

- Cullen, N.J., et al. (2013). A century of ice retreat on Kilimanjaro: the mapping reloaded. Cryosphere, 7:419-431

- Hemp, A. (2009). Climate change and its impact on the forests of Kilimanjaro. African Journal of Ecology, 47(1):3-10

- Kaser, G., et al. (2010). Is the decline of ice on Kilimanjaro unprecedented in the Holocene? The Holocene, 20(7):1079-1091

- Minarcek, A. (2003, September 23). Mount Kilimanjaro’s Glacier Is Crumbling. National Geographic News.

- Mölg, T., et al. (2012). Limited forcing of glacier loss through land-cover change on Kilimanjaro. Nature Climate Change, 2(4):254-258

- Morton, O. (2003, November 17). The Tarps of Kilimanjaro. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2003/11/17/opinion/the-tarps-of-kilimanjaro.html

- Roach, J. (2009, November 2). Kilimanjaro’s Snows Gone by 2022? National Geographic News.

- Thompson, L.G., et al. (2002). Kilimanjaro Ice Core Records: Evidence of Holocene Climate Change in Tropical Africa. Science, 298(5593):589-593

- Thompson, L.G., et al. (2009). Glacier loss on Kilimanjaro continues unabated. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), 106(47):19770-19775

- Zhang, Q., et al. (2015). Vanishing High Mountain Glacial Archives: Challenges and Perspectives. Environmental Science & Technology, 49(16):9499-9500

Figures:

- Earth Observatory News, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2006). [Snow accumulations of Mount Kilimanjaro in 1993 and 2000]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

- Eden, Janine and Jim. (2013). [Photograph of ice core]. Retrieved from FlickrCommons. CC BY 2.0.

- Kristensen, Erik Cleves. (2007). [Photograph of Mount Kilimanjaro]. Retrieved from FlickrCommons. CC BY 2.0.

- Meader, Mary. (1938). [Photograph of Mt. Kilimanjaro in 1938]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Semhur. (2008). [Map of Mount Kilimanjaro with main glaciers, valleys, and peaks]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.