Ch. 1: Key Definitions & Diagnostic Criteria

You may be familiar with terms like “alcoholism,” “drug addiction,” and “alcohol or other drug (AOD) dependence.” These terms all relate to the focus of this chapter which presents current thinking about these concepts and how terminology is used in practice and research. First, several key terms are defined and explained. Then, the diagnostic schemes currently in use are described.

In Module 1, you learned about how the concept of psychoactive substances is defined. Now let’s look into how related concepts are used.

Key Definitions

In Module 1, you learned about how the concept of psychoactive substances is defined—substances (chemicals) “with the potential to cause health and social problems, including addiction” is one way to summarize this (McLellan, 2017, p. 113). Now let’s look into what the concepts of substance use, substance misuse, and substance use disorder actually mean. Because the criteria for substance use disorder include the terms “tolerance” and “withdrawal,” these two terms are also defined for you. Then we can delve into the meaning of “biopsychosocial” with regard to understanding substance misuse and substance use disorders, and the implications of adopting a biopsychosocial perspective in studying different theories.

Substance Use. The concept of substance use is fairly straight-forward: introducing a psychoactive substance into the body/circulating blood stream. As you will learn in this course, there are many ways these different substances are used: drinking, eating, introducing through oral membranes, or otherwise ingesting; inhaling, “snorting,” or introducing through nasal membranes; smoking or otherwise inhaling through lungs; injecting; and, absorbing through skin are all common modes of introduction. The concept of substance use does not distinguish amounts or consequences of use.

Substance Use. The concept of substance use is fairly straight-forward: introducing a psychoactive substance into the body/circulating blood stream. As you will learn in this course, there are many ways these different substances are used: drinking, eating, introducing through oral membranes, or otherwise ingesting; inhaling, “snorting,” or introducing through nasal membranes; smoking or otherwise inhaling through lungs; injecting; and, absorbing through skin are all common modes of introduction. The concept of substance use does not distinguish amounts or consequences of use.

Substance Misuse. Substance misuse implies that substance use occurs in high enough doses or in risky situations such that physical health, mental health, and/or social problems may result (McLellan, 2017). The dose need not be sufficient to cause overdose to be potentially problematic, and the problems may not appear immediately but accumulate over repeated misuse episodes. An example is the difference between using alcohol and binge drinking—the dose consumed during a single drinking episode matters and repeatedly engaging in binge drinking is more problematic than a single episode. In some scenarios, the actual dose consumed may not be as problematic as the situation when/where it is used. For example, using alcohol or cannabis at home might not be problematic but driving under the influence is. Or, a type of substance use might not be problematic for most individuals but is for a woman during pregnancy. And, substance misuse is not defined by the consequences actually experienced but by the potential consequences—many of which can be severe and irreversible, such as exposure to infectious disease, accidental injury (to self or others), legal difficulties/incarceration, and damage to physical or mental health (including, but not limited to overdose or substance use disorder).

Substance Use Disorder (SUD). In order for an individual to be diagnosed or classified as experiencing a substance use disorder, certain specific criteria must be met. Historically, terms like “alcoholism” and “addiction” were applied, but these terms have been applied unsystematically and inconsistently. Instead, a substance use disorder used to be called either substance abuse or substance dependence in the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition). Until recently, and for many years, these diagnostic criteria were applied across much of the U.S. mental and behavioral health system and reported in much of the research literature. At the international level, the World Health Organization’s ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, version 10) served a similar function.

Substance Use Disorder (SUD). In order for an individual to be diagnosed or classified as experiencing a substance use disorder, certain specific criteria must be met. Historically, terms like “alcoholism” and “addiction” were applied, but these terms have been applied unsystematically and inconsistently. Instead, a substance use disorder used to be called either substance abuse or substance dependence in the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition). Until recently, and for many years, these diagnostic criteria were applied across much of the U.S. mental and behavioral health system and reported in much of the research literature. At the international level, the World Health Organization’s ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, version 10) served a similar function.

Tolerance. Because of changes in the brain and body (more about this in Module 3), greater amounts of a substance might be needed if certain substances are repeatedly used over time. In other words, when tolerance to a substance (or type of substance) develops, a person may need to use increasingly higher doses of a drug, medication, alcohol, or other substance to achieve the same psychoactive effects previously experienced at lower doses. (Another way of increasing dose is to use the substance more often—you will see more about this when we look into pharmacokinetic principles). In the DSM-V, acquired tolerance is characterized by either:

- A need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to which tolerance has been developed in order to achieve intoxication or the desired effect; or,

- A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance.

An example demonstrating where acquired tolerance is particularly problematic occurs with individuals who have developed tolerance, are unable to obtain the substance for a period of time, then resume use again at the same level previously used. For instance, someone may have been regularly using heroin at a certain high level prior to being incarcerated in jail, unable to access heroin during their period of incarceration, and resumes using at community reentry following release from incarceration. If the period of abstinence was long enough, the person’s body may have re-adjusted to not having the substance on board, and their tolerance diminished. Resuming use at the previously tolerated level could lead to an overdose in their re-adjusted condition.

Another example where tolerance matters has to do with alcohol consumption. A person consuming enough alcohol to have a blood alcohol level (BAL)/blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of .20 for the first time likely would experience blackout. However, a person who routinely drinks to this BAL/BAC level might have developed sufficient tolerance that, while their functioning is significantly impaired, the effects are more reflective of a lower BAL/BAC outcome for individuals who drink less and drink less often.

Base tolerance differs a bit from acquired tolerance in that it is a person’s tolerance level for the substance prior to regular substance use. Base tolerance is influenced by a person’s biological and genetic makeup and it can be tricky to recognize the implications of this source of individual difference in response to substance use/misuse. For example, individuals who believe “I can hold my liquor better than others” or “I can drink everyone else under the table” also may believe that this is protective from developing an alcohol use disorder or other health consequences related to binge or heavy drinking—believing they have immunity or are “tougher” than others. Unfortunately, this is untrue; in fact, someone who does not feel the effects of alcohol after only a couple of drinks is likely to continue drinking in higher quantities to achieve the desired effect. Meanwhile, the body and organ systems are awash in higher levels of alcohol (and its breakdown/metabolite substances—more about this in Module 3), regardless of the person’s psychoactive experience. The brain, heart, liver, and other organ systems are affected by the higher concentrations circulating in the body. This increased concentration of alcohol is doing greater harm, regardless of how the person feels.

Withdrawal. With many (but not all) substances, a person’s body adapts to the presence of the substances to such an extent that if that substance is no longer available, the person experiences a host of very difficult symptoms (more about this in Module 3). In the DSM-V language, substance withdrawal is evidenced as:

- the characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the particular substance involved, and

- the substance or closely related substances are taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms (e.g., benzodiazepine withdrawal might be reduced with alcohol).

Examples of alcohol withdrawal symptoms, for instance, include high levels of anxiety, sleep disorders, tremors, nausea/vomiting, sweating, racing heart, physical restlessness, and possible seizures. If a person experiences two or more of these symptoms as a direct result of stopping or reducing alcohol intake, and not as a function of some other condition or other substance the person may have used, the person may be diagnosed with alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Examples of symptoms associated with withdrawal from heavy, prolonged cannabis/marijuana use can include: irritability, anger, aggression, difficulty concentrating, nervousness, anxiety, sleep disturbances, vivid unpleasant dreams, decreased appetite/weight loss, restlessness, depression, shakiness, sweating, fever, chills, and headache. Symptoms associated with opioids, where use has been heavy for several weeks or more, can include: depression, nausea/vomiting, muscle pain, runny eyes, runny nose, sweating, diarrhea, fever, and insomnia. The experience of withdrawal from substances can be fraught with misery.

There exist both differences and similarities in withdrawal from different types of substances, not only in terms of symptoms but also in how soon symptoms might appear and how long they might last. Learning about different substances (as we will in Part 2 of the course) is important because withdrawal from some substances that is not medically managed can be fatal. Just quitting may not always be the safest choice—a person may need to be gradually weaned off certain substances to avoid dangerous withdrawal effects on heart rate/rhythm, blood pressure, and severe seizures. Consider the public health implications of large community disasters like the combination of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita that made it impossible for some individuals to access alcohol, other substances, or even prescription medications on which their bodies had come to depend—their withdrawal could contribute to loss of life. This is true if a person’s access is interrupted by the theft of the substances/prescription medications, inability to pay for medications or a pharmaceutical company’s interruption of supply.

There exist both differences and similarities in withdrawal from different types of substances, not only in terms of symptoms but also in how soon symptoms might appear and how long they might last. Learning about different substances (as we will in Part 2 of the course) is important because withdrawal from some substances that is not medically managed can be fatal. Just quitting may not always be the safest choice—a person may need to be gradually weaned off certain substances to avoid dangerous withdrawal effects on heart rate/rhythm, blood pressure, and severe seizures. Consider the public health implications of large community disasters like the combination of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita that made it impossible for some individuals to access alcohol, other substances, or even prescription medications on which their bodies had come to depend—their withdrawal could contribute to loss of life. This is true if a person’s access is interrupted by the theft of the substances/prescription medications, inability to pay for medications or a pharmaceutical company’s interruption of supply.

Withdrawal symptoms and the experience of withdrawal have profound implications for a person’s recovery, especially in the early phase. Withdrawal symptoms may interfere with a person’s ability to function as much as (or even more than) the substance misuse did. You will learn more about this in Module 4 when we look into learning principles and their role in addictive behavior.

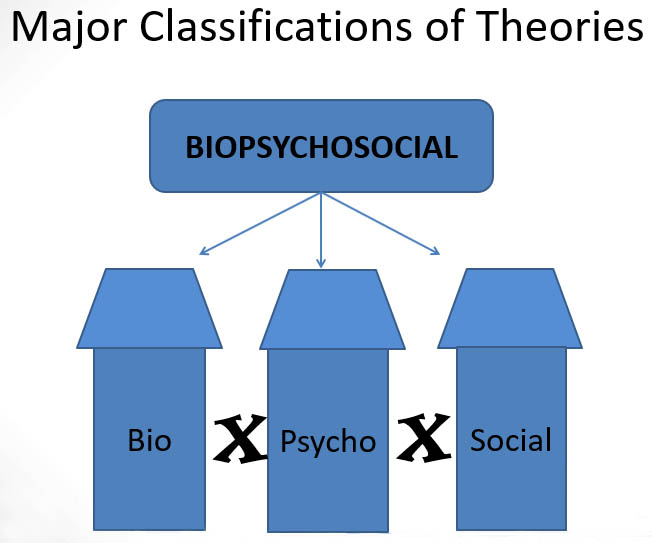

Biopsychosocial Perspective. You may have heard the term “biopsychosocial” in reference to how we think about complex behavioral health issues and human development. In review (or if the concept is new to you), it means that in order to fully understand a phenomenon like substance misuse it is essential to understand the biological, psychological, and social factors involved in its development, maintenance, and resolution. Unfortunately, because of the different disciplines and professions involved, these three domains are often considered individually or distinctly from each other, rather than as an integrated whole—each domain is often considered as a silo, separate from the others (and not always equal to the others). In reality, the three domains interact in important, mutually influential ways. Whether or not someone engages in substance misuse is influenced by that person’s biological makeup and processes, psychological makeup and experiences, and experiences/interactions with the social and physical environment. One thing that all of the research in substance misuse and substance use disorders taken together has taught us is: THERE IS NO ONE SINGLE CAUS, and there is not even any one single domain involved. These are very complex phenomena with multiple interacting causes. It also explains why the experience can be so different among different individuals and why “one size fits all” treatment approaches do not fit all. In the next several modules of our course, we examine each of these domains separately, because within each there exists a great deal of complexity (Module 3=biological, Module 4=psychological, and Module 5=social/physical environmental). Then, in Module 6, we explore ways to bring these domains back together in a more integrated fashion.

Current Diagnostic Criteria

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association adopted a new diagnostic system, the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), informed by decades of additional research into the epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of various psychiatric conditions. This is the main scheme for diagnosing substance use disorders currently used in the U.S. clinically, and increasingly adopted in research. The ICD-10 is in the process of being replaced by the ICD-11. Fairly dramatic changes were seen in the criteria for the diagnosis of substance use disorders. The most dramatic was the change from two distinct categories, abuse, and dependence, to viewing these disorders on a continuum of severity. The list of 11 diagnostic criteria (see Table 1) reflect 4 categories of function:

- impaired control over use [items 1-4]

- social impairment/consequences [items 5-7]

- risky use of the substance(s) [items 8-9]

- pharmacological indicators/symptoms: tolerance, withdrawal [items 10-11]

Table 1. Eleven DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing substance use disorder (SUD)

|

1 |

Often taking alcohol or another substance in larger amounts or for a longer period than intended (e.g., planning to limit yourself to 2 beers but ending up drinking 6) |

|

2 |

A persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use of alcohol or another substance (e.g., believing your substance use is problematic and attempting to cut back on frequency or amount, but failing to do so). |

|

3 |

Spending a great deal of time in activities necessary to obtain, use, or recover from the effects of alcohol or another substance (e.g., spending days planning a drinking event/party then drinking before, during, and after the event/party, and needing a day or two to recover from the drinking event/party; or, having to know/plan where you will acquire the substances when you go on vacation or to travel out-of-town) |

|

4 |

Strong desire, craving, or urge to use alcohol or another substance (e.g., “needing” to smoke a cigarette when driving in the car, with certain friends, or at the end of a meal) |

|

5 |

Failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home resulting from recurrent use of alcohol or another substance (e.g., continually “dropping the ball,” disappointing other people, failing to do what is expected of you at work, academically, at home, such as not feeding your children or pets or failing to provide them with adequate supervision because you are intoxicated, high, or recovering from substance use) |

|

6 |

Continued use of alcohol or another substance despite persistent or recurring problems in social or interpersonal relationships that are caused or made worse by the effects of alcohol or another substance (e.g., continuing to “get high” despite knowing that it is causing relationship problems with your partner/spouse, parents, siblings, or children) |

|

7 |

Giving up or reducing important social, occupational, or recreational activities because of alcohol or other substance use (e.g., no longer engaging in past hobbies/interests or work, family, fun activities in favor of using substances or recovering from use; replacing your “life” with substance use) |

|

8 |

Recurrent use of alcohol or another substance in situations where it is physically dangerous to do so (e.g., operating a car/motorcycle/boat or other vehicle while under the influence, engaging in risky sexual practices while under the influence or to acquire substances, risking harm to self or others) |

|

9 |

Continuing to use alcohol or another substance despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurring physical or psychological problem that could be caused or made worse by its use (e.g., continuing to drink despite its effects on diabetes, liver disease, sleep patterns, or depression) |

|

10 |

Developing tolerance for alcohol or another substance (see definition of tolerance) |

|

11 |

Experiencing withdrawal symptoms or taking alcohol or closely related substance in order to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms (see definition of withdrawal) |

Severity. The DSM-5 diagnosis scheme includes the dimension of severity, based on the number of symptoms an individual is experiencing. Severity is determined as follows:

- mild SUD: 2 or 3 symptoms

- moderate SUD: 4 or 5 symptoms

- severe SUD: 6 or more symptoms

Types of SUD. While moving away from categorizing SUD in categorical terms (abuse/dependence) the DSM-5 (and the ICD-11) does distinguish between different types of substances involved. Nine types of substance use disorder are identified, each of which utilizes the 11 criteria and severity schedule above (see Table 2).

Table 2. Types of substance use disorder classified in DSM-5.

|

DSM-5 Code |

Type of Substance |

|

F10 |

alcohol |

|

F11 |

opioid |

|

F12 |

cannabis/marijuana |

|

F13 |

sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics |

|

F14, F15 |

Stimulants (the 14 code is specific for cocaine, 15 for amphetamines) |

|

F16 |

hallucinogens (other than cannabis) |

|

F17 |

tobacco |

|

F18 |

inhalants |

|

F19 |

Other/unknown substance use disorder |

Diagnostic systems make a distinction between a substance use disorder (like alcohol use disorder, AUD, or opioid use disorder, OUD) and a substance-induced disorder. Some of what we see in terms of problems related to the use of alcohol or other substances are caused or exacerbated (made worse) by substance use, but do not reflect a substance use disorder per se. For example, sleep disorders may be induced by substance misuse, or depression may result from use or stopping the use of certain substances. Even psychotic episodes might be induced by substance use despite there not being an underlying psychotic mental condition. Clinicians are quick to admit that it is sometimes very difficult to tell these apart and to make an accurate differential diagnosis. However, the distinctions are clinically important because the different processes need to be treated or managed in different ways.

Additionally, the DSM-5 recognizes that someone may use more than one type of substance, termed “polysubstance” use disorder. Caffeine is a special case in the DSM-5 where it is possible that a substance-related disorder exists, but there is not an actual substance use disorder code associated with caffeine. And, finally, it is important to know that the DSM-5 (and ICD-11) recognizes substance withdrawal as being distinct from a diagnosable SUD—the symptoms of substance withdrawal often warrant a separate diagnosis described in the DSM-5.

Before you read on, take a moment to jot down your “best guess” answers to the following questions:

The focus of our course is on substance misuse and substance use disorders. However, many practitioners and scholars argue that the principles apply to other types of behaviors, as well. For example, you may have heard discussions about what some call “process” or “behavioral” addictions:

- Gambling addiction

- Internet/gaming addiction

- Sex addiction

- Shopping addiction

Based on what you have learned so far about defining substance use disorders and addiction, consider the following 3 questions:

- What do you think might be the similarities or differences between a person who experiences an alcohol use disorder and a person with a gambling disorder?

- What about “disordered” internet gaming or other “dependence” on technology?

- What do you think about people using the word “addiction” to describe how they feel about a favorite television show? What about advertisers describing games like Candy Crush as “addicting” to promote its popularity?