Ch. 1: Introduction to Opioids

In this chapter, we examine opioids—what they are, how they are used, how they are misused, their effects, and some statistics concerning their use/misuse. Note that a portion of this chapter’s contents informed and were informed by materials presented in Begun (in press), NAS (2017), DEA (n.d.), and NIDA (2018). For more in-depth information, consider reviewing the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) Learning Academy course America’s Opioid Crisis: A Primer for Social Work Educators and the review by Reber, Schlegel, Braswell, and Shepherd (in press), members of an interdisciplinary team serving children and families in the neonatal intensive care environment.

What are Opioids?

Opioids are substances that interact with naturally occurring opioid receptors in the human body and are either derived from opium or synthetically constructed/manufactured. You may hear the words opioid and opiate being used interchangeably—this is not entirely correct. Opiates are a subset of opioids derived from opium—substances such as heroin, morphine, and codeine are produced from the seeds or what is extracted as a resin from the opium poppy, papaver somniferum (somniferum meaning “bringer of sleep”—you may recall the scene in Wizard of Oz where Dorothy and Toto fall asleep in the poppy field outside of the Emerald City). The poppy seeds we eat in various foods (e.g., poppy seed bagels, lemon poppy seed muffins, poppy seed salad dressing) also come from this plant. Many varieties of this plant do not produce opium in any significant amounts and are grown for ornamental purposes. The opium poppy is most heavily (commercially) harvested in Southeast and Southwest Asia, Mexico, and Columbia, supplying pharmaceutical companies (if not others). A great deal of international economics, policy, policing, and trafficking are involved in opioid production and distribution.

Originally, opioids referred to synthetically or semi-synthetically produced substances. Semi-synthetic substances include opium to some extent but there are synthetic components involved, as well; for example, oxycodone and hydrocodone are semi-synthetic opioid drugs. Purely synthetic opioid examples include methadone, tramadol, fentanyl, and carfentanil. Opioids are manufactured both by licensed/controlled pharmaceutical companies in the U.S. and other countries, as well as illegally produced and distributed by uncontrolled clandestine laboratories around the world (https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/fentanyl.html). The word opioid is now used to describe the whole group of substances that bind with opioid receptors in the brain and body, whether naturally or synthetically occurring. Hence, opiates are generally considered as a group of opioids these days.

Narcotics is another word you may have encountered. Narcotics are substances intended for use in treating moderate to severe pain. Examples of opioid pain medications are:

- oxycodone (OxyContin®, Percocet®)

- hydrocodone (Vicodin®)

- codeine (often combined with acetaminophen or with cough suppressants)

- morphine

- fentanyl, carfentanil, and other fentanyl analogs

The word narcotic refers to the capacity for these drugs to induce a state of narcosis—a state of stupor or unconsciousness produced by narcotics or other substances (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/narcosis). The word narcotic is not much used in health or mental health professions anymore once it became so heavily associated with the legal system and illegal drug trafficking.

The word narcotic refers to the capacity for these drugs to induce a state of narcosis—a state of stupor or unconsciousness produced by narcotics or other substances (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/narcosis). The word narcotic is not much used in health or mental health professions anymore once it became so heavily associated with the legal system and illegal drug trafficking.

Opioid Use

The medical use of opioids is to provide pain relief. Common types include prescription drugs like oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine, and fentanyl, as well as combination medications (e.g., aspirin or acetaminophen plus opioid, such as Percodan®, Percocet®, or Tylox®). Prescription misuse of opioids generally involves pills which are either swallowed or crushed and injected or snorted. Some forms are meant to be absorbed through the skin in a controlled dose, such as the fentanyl patch, or to be administered intravenously (IV) under medical supervision. These drugs are used in human and veterinary medicine.

As learned in Module 6, nonmedical use of opioid drugs may represent a gateway to heroin use: based on 2011 data, about 80% of individuals who used heroin misused prescription opioids first (NIDA, 2019). However, “more recent data suggest that heroin is frequently the first opioid people use. In a study of those entering treatment for opioid use disorder, approximately one-third reported heroin as the first opioid they used regularly to get high” (NIDA, 2019). It is also important to recognize that, in the 2011 data, about 4-6% of individuals who misuse prescription opioids transitioned to heroin: “This suggests that prescription opioid misuse is just one factor leading to heroin use” (NIDA, 2019).

Opioid Use Disorder (OUD)

You learned in an early course module about the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version 5 (DSM-5) criteria for substance use disorder (SUD). The criteria apply to the diagnosis of opioid use disorder (OUD) as one type of SUD. The criteria are not applied when opioid medication is used strictly as prescribed and under medical supervision. The 11 criteria are as presented in your earlier lesson but specifically related to opioid use (APA, 2013):

- opioids often used in larger amounts or over a longer period of time than intended;

- experiencing a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use;

- a great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain opioids, use opioids, or recover from opioid use effects;

- experience of craving, or a strong desire to use opioids;

- recurrent opioid use resulting in failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home;

- continued opioid use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of opioids;

- important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of opioid use;

- recurrent opioid use in situations where it is physically hazardous;

- continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem likely caused or exacerbated by opioid use;

- developing opioid tolerance, as defined by either: (a) a need for markedly increased amounts of opioids to achieve intoxication or desired effect, or (b) markedly diminished effect with continued use at the same opioid amount/dose; and

- experiencing withdrawal, as manifested by either: (a) the characteristic opioid withdrawal syndrome, or (b) the same or closely related opioid substance taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms.

A diagnosis of OUD is made when 2 or more of these 11 symptoms are present during the same 12-month period. Severity of the diagnosed opioid use disorder (OUD) is determined by the total number of these 11 symptoms experienced:

- mild OUD (2-3 symptoms),

- moderate OUD (4-5 symptoms), or

- severe OUD (6 or more symptoms).

Opioid Effects

Opioid medications are used medically for their ability to control pain (analgesic effects), as well as to reduce/control/suppress coughing and diarrhea. In addition to pain relief, opioids confer a general sense of well-being, relaxation/reduced tension, reduced anxiety, reduced aggression, and potentially a state of euphoria. Opioids also cause drowsiness, difficulty concentrating, apathy/lack of motivation, slowed physical activity/reactions, constricted pupils, constipation, nausea/vomiting, and slowed breathing (DEA, n.d.; NIDA, 2019). The psychoactive effects of opioids come from their bonding to naturally occurring opioid receptor sites on neurons, leading to a surging release of dopamine to the pleasure areas of the brain, blocking pain, and rewarding the substance use behavior. The surge in “pleasure” from exogenous opioid use is many times greater than naturally occurs at opioid receptor sites from endogenous sources, such as pleasure from eating or sex. Because the brain adapts to the presence of the extrinsically introduced opioids, tolerance occurs with repeated use and withdrawal symptoms appear when use is stopped. At this point, a person may take the drugs not so much to “get high” as to avoid or reduce the low or negative feelings that occur without the drug.

Opioids are powerfully psychoactive and addictive, with chronic use accompanied by the development of tolerance, as well as withdrawal symptoms: watery eyes, runny nose, yawning, sweating, restlessness, irritability, loss of appetite, nausea, tremors, increased heart rate, increased blood pressure, chills, flushing, drug craving, and severe depression (DEA, n.d.). Withdrawal symptoms generally disappear over days to weeks without additional dosing, depending on the type of substance involved and the severity of the physical/psychological addiction developed. The experience of craving and depression may persist much longer, contributing to a heightened risk of suicide during early recovery. Other than overdose risk, the greatest acute danger of opioid misuse is the effect of slowing (or stopping) a person’s breathing, an effect compounded by combining opioids with some other substances with this same effect (e.g., alcohol, barbiturates). Other opioid effects include sleepiness, confusion, possible pneumonia. Over time, opioid use/misuse can lead to insomnia and increased sensitivity to pain—despite being used to control pain, a person’s pain tolerance threshold may be lowered with chronic opioid use/misuse. Heroin use may also lead to liver and kidney disease (NIDA, 2018).

Physical dependence on opioids can develop even when used as medically prescribed; a person may become dependent on the class of substances, such that heroin and prescription misuse may become intertwined depending on a person’s access to the different substances. Heroin and other opioids are frequently combined with other substances to amplify their effects or to counter some of their side or withdrawal effects. Opioids like fentanyl or carfentanil may be added to heroin (or other substances) to amplify effects and increase drug trafficking profits (Taxel, 2019). Because these added substances are many times more potent than the primary substance, their addition greatly increases the risk of overdose.

Mode of administration. Depending on the mode of administration, opioid misuse may increase the risk of infection and infectious disease exposure. Since many individuals engage in injection use of these substances, this is of significant concern and worthy of harm reduction attention. Heroin (“horse,” “smack”) is generally injected, smoked, or sniffed/snorted. The avenue of administration can amplify the addictive potential of heroin or other opioids—the faster the drug reaches the brain in large concentration, the greater the addictive potential (i.e., injection is faster than oral drugs). The avenue of administration also may introduce additional risks, such as injection site infection, injection site vein collapse, and exposure to infectious diseases, such as HIV and hepatitis (Rassool, 2011).

Opioid overdose. The symptoms of a heroin overdose as described by Rassool (2011, p. 73), include:

- shallow breathing or difficulty breathing

- weak pulse and/or low blood pressure

- delirium

- drowsiness

- muscle spasms

- disorientation

- bluish-color of lips and fingernails (from low oxygen levels)

- dry mouth

- pinpoint (small) pupils

- coma.

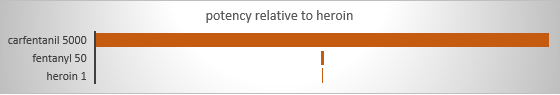

Obviously, the risk of a dangerous or fatal overdose is tied to the amount of a substance used. However, amounts are relative depending on the potency/strength of the substance. Fentanyl is recognized as contributing to a significant surge in overdose events and deaths—pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl is 50 times stronger than the average potency of heroin (CDC, 2018). One reason it becomes even more dangerous is that it often is added to illegally distributed substances, like heroin (but also other types), without the knowledge of persons using them. The person is unknowingly delivered a more potent dose than accounted for, contributing to their overdose risk: increased opioid overdose death rates “are being driven by increases in fentanyl-involved overdose deaths, and the source of the fentanyl is more likely to be illicitly manufactured than pharmaceutical” (CDC, 2018). Dosing uncertainty is compounded by uncertainty as to the strength/concentration of illegally manufactured opioids, including fentanyl and its variants (analogs). While not as common an opioid problem as fentanyl, pharmaceutically produced carfentanil, intended for use in large animal veterinary care (e.g., elephants), has 100 times the potency of fentanyl (5,000 time the potency of heroin). This diagram visually shows these ratios.

Another contributor to overdose happens after a person has developed opioid tolerance and uses these substances at an increasingly higher level (dose) over time. Then, if the person ceases using the drug either as a result of treatment/recovery efforts, hospitalization, during a period of incarceration, or for some other reason (e.g., no access following a community-wide natural disaster disrupting distribution), tolerance reverts to a lower level (dose). Individuals unaware of this change in tolerance may resume use at their prior higher tolerance level, amounting to an overdose at their current lower tolerance level. This phenomenon is suspected as a contributor to relatively high mortality rates observed among formerly incarcerated individuals in the days immediately following release from jail or prison.

Opioid overdose reversal. Opioid overdose might be reversed by administering naloxone (Narcan® or Evzio®). As an opioid antagonist, naloxone binds to opioid receptors in the body and blocks the opioid’s effects. The amount of opioid reversal drug needed depends on the dose and strength of the opioid involved in the overdose event. This means the overdose reversal drug needs to be available, available in a quantity sufficient for managing the overdose event, and someone needs to be able to administer it in the event of overdose. The opioid overdose reversal drug puts the person into immediate withdrawal, which is exactly what the person may have been using the opioids to avoid. It can be life-saving, however, since it can restore normal breathing suppressed by an opioid overdose. Many communities and institutions have adopted naloxone distribution programs, policies, and Good Samaritan laws allowing lay persons on the scene to administer the overdose reversal care before professionally trained first responders can do so and making it easier for individuals to obtain and carry a reversal kit for use in the event of an overdose. Ideally, an overdose incident can be followed up with outreach efforts designed to engage the individual in OUD treatment—handling the event as a “reachable” moment.

Medication for treating opioid use disorder (MOUD). Treating opioid use disorder (OUD) often involves prescribed medications as part of an evidence-based intervention plan—medication assisted treatment (MAT). Three medications have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this purpose and have a strong evidence base supporting their use: methadone (itself a synthetic opioid), buprenorphine (an opioid partial agonist), and naltrexone (an opioid antagonist). Additional medications are in trial for treating OUD, as well (Portelli, Munjal, & Leggio, 2018). These medications work on the same brain opioid receptor systems affected by opioid misuse—humans naturally have opioid receptors in the brain and some other parts of the body.

Like any medication, there are advantages and disadvantages to their use. The primary take-home messages about medication assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: the success rates in retaining individuals in treatment and reducing the illicit use of opioids is greater with MAT than without (and better than placebo), and MAT (plus counseling) is more cost-effective than treatment without medication. Despite this mounting evidence, medication in treating opioid use disorder currently is grossly underutilized (Portelli, Munjal, & Leggio, in press). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, in its Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) #63 (SAMHSA, 2018), and Portelli, Munjal, and Leggio (in press) compared these three options for medication assisted treatment (SAMHSA, 2018).

Methadone. Methadone is used both in medically supervised withdrawal from opioids (short-term) and longer-term recovery maintenance. It is a Schedule II controlled substance, having addictive potential itself, and is generally only legally distributed through specially licensed/federally certified opioid treatment programs or inpatient hospital settings treating opioid use disorder. Methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) is the primary and most researched approach to use of methadone in treating OUD.

One main advantage of methadone over heroin is that it is longer acting, so that it is dosed daily rather than heroin which is taken multiple times per day to avoid withdrawal symptoms. This creates a more even psychoneurological experience of withdrawal which supports opioid abstinence goals. As an agonist, it creates some of the same effects as opioids/heroin (respiratory depression, sedation, heart rhythm changes, low blood pressure, constipation), but in a more controlled dosing pattern and at a level insufficient to create a “high” when used as prescribed. Methadone “helps individuals experiencing OUD reduce withdrawal symptoms and craving for opioids by delivering the desired drug effect over a longer period than the abused substances” (Portelli, Munjal, & Leggio, in press). Pharmaceutical-grade methadone is more predictable, and presumably safer, than illicit substances. Methadone can be gradually tapered off to eventually leave a person opioid-free and is known to reduce risk of overdose-related death, as well as harms associated with illicit opioid misuse (e.g., HIV/Hepatitis infection and criminal activity; SAMHSA, 2018). Because of its effectiveness, the World Health Organization (WHO) “lists it as an essential medication” (SAMHSA, 2018). An advantage of methadone controls is that programs have the potential to engage recipients in other recovery-support services, as they must attend the program daily to receive the medication.

Methadone is considered a safer alternative to illicit opioids for opioid use disorder management during pregnancy since it reduces the occurrence/cycles of withdrawal which pose a significant risk to the fetus and viability of the pregnancy (causing premature labor contractions, among other risk events). However, the baby has a high likelihood of experiencing neonatal withdrawal syndrome (NWS) at birth and will need to be weaned off the methadone just as in the case of any other opioid.

Buprenorphine. Buprenorphine is used both in medically supervised withdrawal from opioids (short-term) and longer-term recovery maintenance. It is a Schedule III controlled substance originally introduced for pain management. It may be prescribed outside of federally certified opioid treatment programs by professionals with a prescribing waiver, distributed by a pharmacy, making it more easily accessible than methadone. As a partial agonist, buprenorphine has some of the same effects as opioids (respiratory depression) without creating the “high” when used as prescribed, but it also may precipitate some degree of opioid withdrawal symptoms (nausea, sweating, insomnia, pain). For this reason, adhering to the treatment may be more difficult than with methadone. Buprenorphine does have some addictive potential but less so than methadone. Risks are greater when combined with use of other drugs that affect breathing (e.g., benzodiazepines). It can be delivered by monthly injection as a slow-release option is available. Naloxone (an opioid antagonist that precipitates opioid withdrawal symptoms and used in opioid overdose reversal) is sometimes combined with buprenorphine to help prevent its misuse. Buprenorphine allows for gradual tapering to eventually no longer needing opioids or medication to manage withdrawal. Because of its effectiveness, the World Health Organization (WHO) “lists it as an essential medication” (SAMHSA, 2018). Buprenorphine may cause neonatal withdrawal syndrome (NWS) but is considered safer than alternatives—however, pregnant women may be less likely to remain in buprenorphine treatment than with methadone, which increases risks to the fetus and pregnancy (see CSWE course, America’s Opioid Crisis).

Naltrexone. Naltrexone is used in opioid use disorder relapse prevention after medically supervised withdrawal. As an opioid antagonist, it blocks opioid receptor sites, acting in a longer-acting manner but similarly to the overdose reversal drug, naloxone. Thus, Naltrexone minimizes the rewarding effects of opioid use, but also can precipitate opioid withdrawal. It requires a prescription but is available through primary care providers without specialty waivers or certification as an opioid treatment program. It does carry a risk of potential side effects (nausea, anxiety, depression, insomnia, liver toxicity, suicidality, sedation, loss of appetite, dizziness, muscle cramping). In addition, because it can precipitate withdrawal, it reduces pre-existing tolerance so that if a person relapses to using opioids, the risk of overdose is increased. Naltrexone in a monthly injectable form was equally effective to oral buprenorphine in maintaining post-withdrawal opioid abstinence in one study, and in another, showed a lower rate of relapse than no medication (SAMHSA, 2018).

Opioid Use Statistics

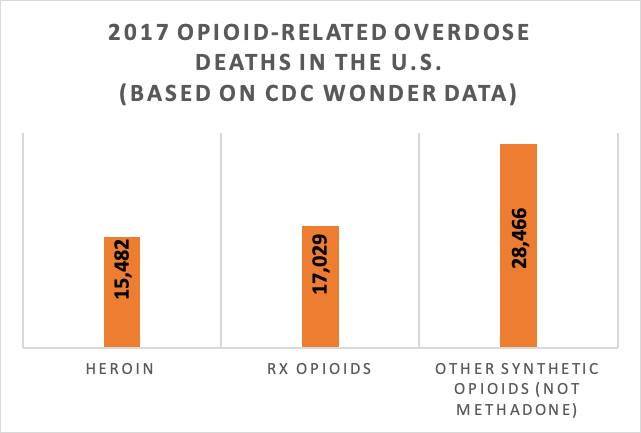

Global data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC, 2019) indicate that opioid use accounted for 66% of deaths attributed to drug use disorders during 2017 and that 1.1 percent of the global population (53.4 million persons) aged 15-64 years engaged in opiate and/or use of prescription opioids for non-medical purposes. The problem was greatest in North America (4% of the population used opioids in the past year). More than 28,000 deaths in the U.S. during 2017 involved synthetic opioids (not including methadone)—a significant increase from 2016—with the highest death rates in West Virginia, Ohio, and New Hampshire (CDC, 2018). These increases are reported to be driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl-involved overdose. This figure shows the number of opioid-involved overdose deaths during 2017, comparing heroin, prescription (Rx) opioids, and other synthetic opioids—mostly fentanyl (https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates). These numbers were all greater than the numbers of overdose deaths attributed to cocaine (13,942), benzodiazepines (11,537), psychostimulants other than cocaine (10,333), or antidepressants (5,269). Opioid-related deaths in the U.S. increased by over 290% in the 15 years between 2001 and 2016, from 0.4% of all deaths to 1.5%, and represented 20% of deaths among 24- to 35-year-olds during 2016 (Gomes, et al., 2018). In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency, stating that over 130 individuals died every day (47,600 in a year) from opioid-related drug overdose and problems of opioid addiction (https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index.html).

While profoundly disturbing, deaths due to overdose are not the only statistics of concern regarding opioid misuse in the U.S. For example, neonatal withdrawal syndrome (NWS) rates in 2015 multiplied by 8 times the 2006 rate in Ohio (https://www.wcbe.org/post/rate-ohio-babies-born-addicted-drugs-increasing) and children’s services in Franklin County Ohio reported 70% of children under one year of age and 28% of all children in their custody had parents using opiates at the time of removal from the home (https://adamhfranklin.org/opiateactionplan/). Again in Franklin County Ohio, for every overdose death, there were 32 emergency department visits. According to data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH, 2018), over 3 million individuals aged 12 and over were estimated to engage in current (past month) opioid use outside of what was medically prescribed. The good news: the 2018 estimate of 3.042 million is lower than 2017 estimate of 3.549 million, a statistically significant difference. The following table presents statistics by age group for several pieces of information concerning non-prescription use of pain relievers (synthetic opioids) and heroin (estimated numbers across the U.S. and percent of population). Harm perception and lack of access are two important components in preventing substance misuse and the youngest group was least likely to perceive harm, although they were also the least likely to perceive having easy access.

|

|

|||

|

|

12-17 years |

18-25 years |

26+ years |

|

# past month use pain relievers not prescribed |

161,000 |

475,000 |

2,216,000 |

|

# past month heroin use |

8,000 |

61,000 |

285,000 |

|

#substance use disorder: pain relievers |

104,000 |

248,000 |

1,343,000 |

|

#substance use disorder: heroin |

4,000 |

101,000 |

421,000 |

|

% great harm perceived: heroin try once or twice |

64.5% |

82.5% |

89.3% |

|

% great harm perceived: heroin use once or twice a week |

84.0% |

93.3% |

95.7% |

|

% perceiving heroin fairly or very easy to obtain |

8.1% |

14.5% |

18.0% |

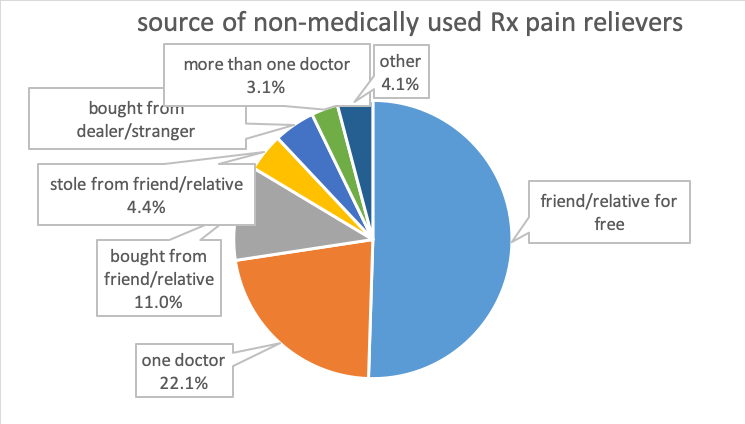

The 2018 Monitoring the Future study reported the lowest rates for 12-graders’ past-year misuse of prescription opioids since 200—about 3.4%, which represents a 64% decline (http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pressreleases/18drugpr.pdf). According to data from the 20125 NSDUH survey, most individuals (97.5%) prescribed opioid pain relievers did not misuse them (Hughes et al., 2016). Among individuals aged 12 and older who did misuse prescription opioids, according to 2013-2014 NSDUH data, their most common source was from a friend or relative for free; the second most common was from a single prescribing doctor (Lipari & Hughes, 2017; see the figure recreated from data presented in Lipari & Hughes, 2017). Recent initiates and those occasionally engaged in prescription pain reliever misuse were far more likely to report friend/relative for free as their source than individuals engaged in frequent use; the latter group was more likely than the others to report their source as one doctor or bought (either from friend/relative or drug dealer/stranger) (Lipari & Hughes, 2017).

A variety of responses have potentially cut into the ease-of-access from prescribers (reporting systems, prescriber education), as well as family/friends (drug take-back programs, public education efforts).